Abstract

The invasiveness of breast cancer cells was shown to be associated with the suppressed ability to develop apoptosis. The role of cell death DNases/endonucleases has not been previously examined in relation with the invasiveness of breast cancer cells. We have compared the activity of the endonucleases in seven human breast cancer cell lines different in the level of invasiveness and differentiation. The invasiveness of cell lines was confirmed by an in vitro Matrigel-based assay. The total endonuclease activity in the differentiated non-invasive (WDNI) cell lines was higher than that in the poorly differentiated invasive (PDI) cells. The expression of EndoG strongly correlated with the degree of estrogen receptor expression and showed an inverse correlation with vimentin and matrix metalloproteinase-13. The EndoG-positive WDNI cells were more sensitive to etoposide- or camptothecin-induced cell death than EndoG-negative PDI cells. Silencing of EndoG caused inhibited of SK-BR-3 WDNI cell death induced by etoposide. Human ductal carcinomas in situ expressed high levels of EndoG, while invasive medullar and ductal carcinomas had significantly decreased expression of EndoG. This correlated with decreased apoptosis as measured by TUNEL assay. Our findings suggest that the presence of EndoG in non-invasive breast cancer cells determines their sensitivity to apoptosis, which may be taken into consideration for developing the chemotherapeutic strategy for cancer treatment.

Keywords: endonuclease G, DNase I, breast cancer, invasiveness, differentiation, chemotherapy, apoptosis

Introduction

Increased breast cancer cell invasiveness is associated with progression and a poor prognosis in patients [1, 2]. Commonly, invasive carcinomas have less apoptosis and are more resistant to chemotherapy [3–5]. Several studies showed decreased apoptosis in breast cancer cells in association with cancer progression, invasiveness and metastases [3, 4]. Histological analysis of human breast carcinomas showed that poorly differentiated breast tumors, but not well-differentiated breast tumors, have decreased apoptosis, which seems to be important in carcinogenesis and progression [5].

Apoptosis is known to play a major role in carcinogenesis and tumor development. Suppression of apoptosis was proposed to cause inappropriate survival of genetically aberrant cells during carcinogenesis [6]. The neoplastic transformation of mammary epithelial cells has been related to decreased apoptotic cell death [7].

DNA fragmentation, a commonly accepted marker and metabolic pathway of apoptotic cell death, is generated by a member of the recently identified group of cell death endonucleases [8]. Anticancer drugs induce apoptosis in cancer cells through endonuclease-mediated DNA fragmentation [9, 10], while the inhibition of endonucleases has a protective effect on cancer cell death [10]. Cell death endonucleases include deoxyribonuclease I (DNase I) [11], deoxyribonuclease II (DNase II) [12], endonuclease G (EndoG) [13], caspase-activated DNase (CAD) [14], and DNase gamma [15]. All these enzymes, except DNase II, require Ca2+, Mg2+ or Mn2+ ions for their activity. The enzymes differ in certain catalytic characteristics and DNA sequence specificity, however they produce a similar type of DNA damage, which consist of single- and double-strand DNA breaks [8, 16]. While being considered as downstream effectors of apoptotic cascades, the cell death endonucleases can cause DNA fragmentation and irreversible cell death seemingly by acting alone after activation, overexpression or introduction into a living cell [11–15].

The role of cell death endonucleases in any cancer, including breast cancer, has not been investigated yet. The present study was aimed to determine the changes of endonucleases in breast cancer cells that are different by their degrees of differentiation and invasiveness. Our study showed that normal breast cells express DNase I and a Mn-dependent endonuclease similar to EndoG. We compared four cell lines that are well-differentiated non-invasive (WDNI) cells (MCF-7, AU-565, ZR-75-1 and SK-BR-3) with three poorly differentiated invasive (PDI) cell lines (HCC1143, HCC1954 and HCC1395). The expression of ER was used as a marker of breast cell differentiation, whereas vimentin, matrix metalloproteinase-13 (MMP-13) and Matrigel-invasion assay were used to measure invasiveness. We found that DNase I activity determined by substrate gel electrophoresis was present only in well-differentiated MCF-7 breast cancer cells and tumor xenografts produced by these cells. Unexpectedly, we found that EndoG determined by using Western blotting was expressed in WDNI cells, whereas expression in PDI cells was extremely low. We further demonstrated that EndoG-positive cells are more sensitive to cell death induced by etoposide. We also showed that human invasive carcinomas have a decreased expression of EndoG and decreased endonuclease-mediated apoptosis. Taken together, our data suggest that the presence of EndoG in non-invasive breast cancer cells determines their sensitivity to apoptosis.

Materials and Methods

Animals

DNase I-knockout (KO) mice (CD-1 background) were provided by H. Mannherz of the University of Bochum, and T. Moroy of the University of Essen, Germany. The mice were bred as heterozygotes and genotyped by PCR as suggested by Napirei et al. [17]. Mammary glands were obtained from fourteen days pregnant female mice. Adult female BALB/c-nu/nu mice, 8–10 weeks of age were used as host animals for xenografted tumors. The tumors were initiated from monolayer cell cultures of MCF-7 and ZR-75-1 cells, as well as BT-474 (ATCC # HTB-20) cells. Approximately 3.5 x 105 cells suspended in 10 μl of Ca2+- and Mg2+-free Hanks’ balanced salt solution were inoculated intradermally into the left mouse flank. The animals received a weekly percutaneous administration of 100 μg of 17β estradiol (Sigma) in 10 μl of ethanol until tumors reached approximately 150–200 mm3. All experiments with animals were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System.

Cells and treatment

All breast cancer cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Well-differentiated cell lines included MCF-7 (ATCC # HTB-22), AU-565 (ATCC # CRL-2351), ZR-75-1 (ATCC # CRL-1500) and SK-BR-3 (ATCC # HTB-30). Poorly differentiated cells were: HCC1143 (ATCC # CRL-2321), HCC1954 (ATCC # CRL-2338) and HCC1395 (ATCC # CRL-2324). Well-differentiated cell lines were expressing ER or HER-2/neu, and were initially isolated from non-invasive tumors. Poorly differentiated cell lines did not express ER (except HCC1395 cells), progesterone receptor or HER-2/neu. All cells were maintained in media and growth conditions (5% CO2 - 95% air in humified incubator at 37°C) suggested by the supplier. To induce cell death, camptothecin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or etoposide (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to serum-free media for 24 h. After exposure to camptothecin or etoposide, the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) was used. Toxicity was expressed as the ratio of LDH release in the medium of treated cells media to that of the maximal LDH release.

EndoG siRNA silencing

SK-BR-3 cells were seeded in 6- or 96-well plates and grown to 60–70% confluence. To knockdown EndoG mRNA, cells were transfected with designed siRNA duplexes (sense siRNA 5’-AUGCCUGGAACAACCUGGAdTdT-3’ antisense siRNA 3’-UCCAGGUUGUUCCAGGCAUdTdT-5’) or Control Non-Targeting siRNA #1 (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO). The cells were treated with 50 nM siRNA mixed with TransIT-TKO transfection reagent (Mirus, Houston, TX) according to manufacturer recommendations in serum-free medium for 24 to 96 h. EndoG mRNA expression was measured using real-time RT-PCR of the extracted total RNA. In experiments with etoposide treatments, the cells were transfected with anti-EndoG siRNA in 96-well plates for 72 h. The medium was exchanged to serum-free medium and cells were exposed with etoposide for additional 24 h.

RNA extraction and real-time RT-PCR

The total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini kit from Qiagen as suggested by the manufacturer. The quality of RNA was determined in 1.2% formaldehyde-agarose gel. Reverse transcription reaction was performed using the GeneAmp Gold RNA PCR core kit (Applied Biosystems) using Oligo d(T)16. In general, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed in a 50-μl reaction followed by real-time RT-PCR in a 25-μl reaction using SmartCycler (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA). Reaction mix was prepared using Platinum SYBR Green qPCR Supermix-UDG (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer recommendations and primers: 5’-CTACCTGAGCAACGTCGCG-3’ and 5’-TCCAGGTTGTTCCAGGCATT-3’. 18s ribosomal subunit RNA was amplified in parallel reaction using primers 5’-TTCGAACGTCTGCCCTATCAA-3’ and 5’-ATGGTAGGCACGGCGACTA-3’. Two-temperature cycles with annealing/extension temperature at 62°C for EndoG and 64°C for 18s were used. The fluorescence was measured at the end of annealing step. The melting curve analyses were performed at the end of the reaction (after 45th cycle) between 60°C and 95°C to assess the quality of the final PCR products. The threshold cycles, C(t) values were calculated by fixing the basal fluorescence at 15 units. cDNA samples were diluted for real-time 1:5 and 1:200 for EndoG and 18s respectively. Three replicate reactions were performed for each sample and the average C(t) was calculated. The standard curve of the reaction effectiveness was performed using the serially diluted (5 points) mixture of all experimental cDNA samples for EndoG and 18s separately. Calculation of the relative RNA concentration was performed using Cepheid SmartCycle software (Version 2.0d). Data are presented as ratio of EndoG/18s mRNA.

Cell extracts

Cells (2−4 x 106) were grown as described above and rinsed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Cells were suspended in Buffer A containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.9, 0.25 M sucrose and the Complete Mini Proteinase Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) (1 tablet/10 ml) and homogenized using a minihomogenizer (Fisher Scientific, Houston, TX). The samples were sonicated in the Virsonic 475 (Virtis, Gardiner, NY) (5 x 20 sec) to decrease viscosity. DNA was precipitated out from the extract by centrifugation at 195,000 x g for 2 h. The extracts were dialyzed against storage buffer (55% Glycerol, 10mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 0.5mM DTT) and stored at −20°C for up to 2 weeks without loss of activity. The protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method [18].

Plasmid incision assay (PIA)

This assay was used for the quantification of endonuclease activity as previously described [19]. Endonuclease activity was measured in 20 μl samples containing 1 μg plasmid pBR322 DNA (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA), 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.7, 25 μg/ml bovine serum albumin V fraction, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2 and 2 μl of cell culture media or cell extract in serial dilutions 1:5. The cation requirements were measured using other salts instead of MgCl2 and CaCl2. After 1 h incubation at 37°C, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 5 μl 1% SDS, 100 mM EDTA. Then digested DNA was subjected to 1% agarose gel electrophoresis at 7 V/cm for 1 h at room temperature. The gel was stained in 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide solution for 20 min and photographed under UV light. The EagleEye scanning densitometer (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was utilized to quantify the relative amount of endonuclease-treated plasmid DNA present in a covalently closed circular DNA (form 1), open circular DNA (form 2) or linear DNA (form 3). One DNase/endonuclease unit was the amount of the enzyme required to convert 1 μg DNA form 1 to DNA forms 2 and 3.

DNA substrate gel electrophoresis (DNA-SDS-PAGE)

This method was used for the detection of DNase I activity according to the previously described procedure [20]. Protein (60 μg/well) was separated by DNA-SDS-PAGE substrate gel electrophoresis using 11.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel containing heat-denatured nicked rat liver DNA. Gels were incubated in the presence of 5 mM MgCl2 and 2 mM CaCl2 and stained with ethidium bromide. DNase was identified as a black band on a bright red background of undigested DNA. The molecular mass of the enzyme was detected in the presence of Kaleidoscope prestained standards (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

EndoG Western blotting

Protein was separated in 11.5% gel according to the Laemmli procedure [21]. The total protein extract from cells (10–20 μg) was dissolved in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 1% SDS, 2 mM EDTA, 1% 2-mercaptoethanol and 7.5% glycerol, and denatured by heating at 100°C for 10 min. Electrophoresis was performed at 100 V for 2 h. Proteins were transferred onto the nitrocellulose membrane in Novex transferring buffer (Invitrogen) at 40 V for 3 h. After soaking in the blocking solution overnight at 4 °C, the membrane was incubated with polyclonal anti-EndoG (Chemicon) diluted 1:1000, washed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) and primary antibodies have been detected with anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) using SuperSignal chemiluminiscent kit (Pierce).

Cell ELISA

Cell ELISA was performed as described by Frahm et al. [22]. Antibody titers and optimal reaction conditions were elaborated prior to the experiment. The cells were seeded in a 96-well plate (10,000 cells/well) and grown in a complete media for 24 h. The cell were washed with serum-free media, permeabilized and fixed with fixative (4% w/v paraformaldehyde, 0.012% saponin, PBS) for 10 min at room temperature. After fixation, cells were washed and rehydrated in PBS and the endogenous peroxidase activity was inhibited by exposure to 0.5% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min at room temperature. Then cells were probed with the primary antibody in blocking buffer (2% BSA, PBS) for 2 h. After triple washing with PBST (0.05% Tween-20, PBS), primary antibody (titers 1:500 – 1:1000) was detected with anti-rabbit antibody (Santa Cruz) conjugated with HRP. The HRP activity was measured with TMB substrate (Sigma) at 450–540 nm using the Synergy HT-I microplate reader (Bio-Tek). After measurement and triple washing, wells were re-probed with anti-actin-FITC antibody (titer 1:10) (Santa Cruz), washed again and fluorescence was measured at 485/528 nm (excitation/emission). All measurements were done in quadruplicates per one marker per one cell line and were repeated at least three times in different plates. Negative controls of primary antibody were done by their substitution by blocking buffer.

In vitro invasiveness assay

Cells suspended in serum-free medium were seeded in the pre-hydrated BD BioCoat Matrigel Invasion Chambers (Becton Dickinson, Bedford, MA) (25,000 cells/insert) and chemoattractant was added to the wells as suggested by the manufacturer. Invasion chambers were incubated in 5% CO2 - 95% air in a humified incubator at 37 °C for 22 h. Invading cells on the bottom of inserts were then fixed with 100% methanol for 2 min, stained sequentially with Mayer’s hematoxylin (Sigma) for 2 min and alcoholic eosin Y (Sigma) for 30 seconds, washed and visualized using light microscopy.

Immunohistochemistry and image analysis of breast cancer tissue microarray

MaxArray™ human breast carcinoma tissue microarray slides were purchased from Zymed Laboratories, Inc. (South San Francisco, CA). According to the manufacturer, every slide contained 60 breast cancer tissue samples: 48 infiltrating ductal breast adenocarcinomas (DAC), 1 breast mucinous carcinoma, 5 medullary carcinomas (MC), 3 ductal carcinomas in situ (DCIS), 2 tubular breast cancers and 1 infiltrating nodular adenocarcinoma. Paraffin sections were deembedded and prepared for staining as described in the manufacturer’s instructions. Sections were probed with anti-EndoG antibody (dilution 1:800) at 4°C overnight. The primary antibody was detected with anti-rabbit IgG-AlexaFluor 594 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Additional sections were subjected to terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining with the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN). After washing and counterstaining with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) sections were mounted under coverslips using the Antifade kit (Molecular Probes) and analyzed under an Axioskope-2 (mot plus) microscope (Carl Zeiss, Göttingen Germany) with green filter set #31001, red filter set #11010v2 and blue filter set #31000 from Chroma Technology Corp. (Rockingham, VT). Images and acquisitions were done using digital camera AxioCam Mrm (Carl Zeiss) and software Axiovision 3.1 (Carl Zeiss). Images were transformed to the grey scale tag image file format and analyzed with ImageJ (version 1.30v) software (NIH, USA). For that, the epithelial compartment was traced manually in every image. Optical densities (from 0 to 255) of red (EndoG) and green (TUNEL) spectra were measured and averaged from 5 different images of every tissue sample. Correlation analysis was performed with entire tissue microarray.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA and Student’s t test. Correlation was calculated using the Pearson correlation analysis. Results were expressed as mean ± SEM.

Results

Endonucleases in normal breast tissue

Our previous studies of the kidney tubular epithelium have shown that three endonucleases are mainly expressed in this tissue: DNase I, DNase II and endonuclease G (EndoG), while the expression of other endonucleases was negligible [23]. The activities of these three endonucleases are different in their cation requirements: DNase I is a mainly Ca/Mg-dependent endonuclease [20], EndoG is a preferentially Mn-dependent enzyme [24], and DNase II does not require cations and is active in acidic conditions [25, 26]. To determine whether these or other endonucleases are expressed in normal breast epithelium, we used DNase I knockout mice recently developed by Napirei et al. [17]. Our experiments have shown that inactivation of the DNase I gene was associated with a marked 40% decrease of Ca/Mg-dependent endonuclease activity determined by the PIA (Fig. 1A). The activity in conditions optimal for DNase II (acidic pH, EDTA) was minimal, indicating that DNase II was not active in breast epithelium. The rest of the activity was mainly Mn-dependent (Fig. 1B) suggesting that EndoG is also a major endonuclease in breast cells.

Fig 1.

Mn-dependent endonuclease (EndoG) is the second major endonuclease in normal breast epithelium as determined by the inactivation of DNase I. (A) Ca/Mg-dependent endonuclease activity in total extracts from normal breast tissue isolated from DNase I knockout and wild-type mice (n = 4 in each group, *P < 0.01) as measured by PIA. (B) After inactivation of DNase I, a Mn-dependent activity is the most prominent in extracts from DNase I KO mice. Cont, control non-digested pBR322 DNA; Ca, 2 mM CaCl2, pH 7.5; Mg, 2 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5; CM, 2 mM CaCl2 + 2 mM MgCl2,; Mn, 2 mM MnCl2, pH 7.5; CMZ, 2 mM CaCl2 + 2 mM MgCl2 + 2 mM ZnCl2; E5, 2 mM EDTA, no cations, pH 5. Oc-DNA, open circular DNA (relaxed rings with one or more single strand breaks); l-DNA, linear DNA (plasmid linearized by a single double strand break); ccc-DNA, circular covalently closed DNA (intact plasmid without breaks), d-DNA, digested DNA.

Endonucleases in breast cancer cell lines

To measure cellular endonucleases, total protein extracts were prepared from well-differentiated and poorly differentiated breast cancer cells. The endonuclease activity assayed by PIA was much higher in WDNI cells than in PDI cell lines (Fig. 2A).

Fig 2.

Total endonuclease activity and DNase I in breast cancer cells. (A) Endonuclease activity in total protein extracts from human breast cancer cells (top panel) and extracellular activity released into serum-free culture medium after 24 h incubation (bottom panel) as measured using PIA. (B) DNase I zymogram gel electrophoresis of total protein extracts from breast cancer cells (left panel) and tumor xenografts (right panel).

Further we examined the activity of DNase I in WDNI and PDI breast cancer cells. DNase I is the only known secreted enzyme among cell death endonucleases [11]. Since serum contains large quantities of DNase I, after culturing cells to sub-confluence in the presence of serum, they were further maintained in a serum-free medium. To minimize the effect of a spontaneous cell death on our measurements, all cells were harvested before any spontaneous cell death occurred (no floating cells observed under light mircoscopy). The activity of endonuclease secreted into the medium was measured 24 h later by using PIA in the presence of Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions. This approach revealed that well-differentiated cells have more secreted endonuclease than poorly differentiated cells (Fig. 2A, lower panel). MCF-7 had the highest activity of extracellular endonuclease amongst all cell lines. In another approach, we applied zymogram gel electrophoresis, which was previously shown by us to be a convenient method for the detection of DNase I [20]. This method showed that DNase I, visualized as a 34-kDa band in ethidium bromide stained gel, is expressed only in MCF-7 cells, whereas the activity in all other cell lines was below the detection limit of the method (Fig. 2B). As shown by our previous studies, specific activity of DNase I in cultured cells is much lower that in tissues [27]. To produce in vivo breast cancer tumors, MCF-7 and ZR-75-1 cells, as well as another tumorigenic human breast cancer cells, BT-474, were injected in nude mice and xenografts were grown as it was described in Materials and Methods. DNase I assayed by zymogram gel electrophoresis of the protein extracts from the tumors was also active in MCF-7 xenografts, while activity of the DNase in the other tumors was very low (Fig. 2B, right panel). Therefore these data confirmed that MCF-7 cells contain DNase I.

Importantly, the endonuclease activity in breast cancer cells was mainly Mn-dependent similar to EndoG in the DNase I KO mice breast extracts described above (Fig. 3A). We determined that most of the investigated breast cancer cells expressed EndoG and the expression of this enzyme was strongly decreased with the decrease of differentiation from WDNI to PDI cells. Western blotting showed that EndoG is highly expressed in WDNI cells, while its expression in PDI cells is very low (Fig. 3C and 3D).

Fig 3.

EndoG expression in poorly differentiated invasive breast cancer cells is lower compared to well-differentiated non-invasive cells. (A) Cation requirements of endonuclease in total protein extract from breast cancer cells (SK-BR-3 cells) measured by PIA. Cont, control non-digested pBR322 DNA; Ca, 2 mM CaCl2, pH 7.5; Mg, 2 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5; CM, 2 mM CaCl2 + 2 mM MgCl2,; Mn, 2 mM MnCl2, pH 7.5; CMZ, 2 mM CaCl2 + 2 mM MgCl2 + 2 mM ZnCl2; E5, 2 mM EDTA, no cations, pH 5. The endonuclease that is active in breast cancer cells is not DNase I, but rather a Mn-dependent endonuclease, which is most likely EndoG. (B) EndoG Western blotting of total protein extracted from the cells. (C) Quantification of the EndoG by Western blotting (n = 4 in each group).

EndoG-positive non-invasive breast cancer cell lines are sensitive to camptothecin and etoposide

EndoG is an apoptotic endonuclease, that seems to be essential for DNA fragmentation leading to cell death [13, 24]. We tested whether camptothecin or etoposide, two well-known apoptosis inductors and anticancer agents, would be more efficient in the induction of cell death of breast cancer cells which express EndoG. Four cell lines, two from each group, with high and low expressions of EndoG, were chosen for the test. These experiments showed that the EndoG-positive WDNI cells were more sensitive to camptothecin- or etoposide-induced cell death than EndoG-deficient PDI cells (Fig. 4). The cell death induced by either camptothecin or etoposide and measured by LDH release was dose-dependent (Fig. 4). These data indicate that camptothecin- or etoposide-induced breast cancer cell death may be mediated by EndoG and the presence of this enzyme is a requirement for the sensitivity to camptothecin or etoposide.

Fig 4.

Cytotoxicity camptothecin (A) and etoposide (B) to breast cancer cells depends on the presence of EndoG. Well-differentiated non-invasive EndoG-positive cell lines are more sensitive to camptothecin and etoposide. Cells were treated with 2–50 μM camptothecin or 100–300 μM etoposide and cell death was measured by LDH release assay (n = 4 in each group, *p<0.01−0.001).

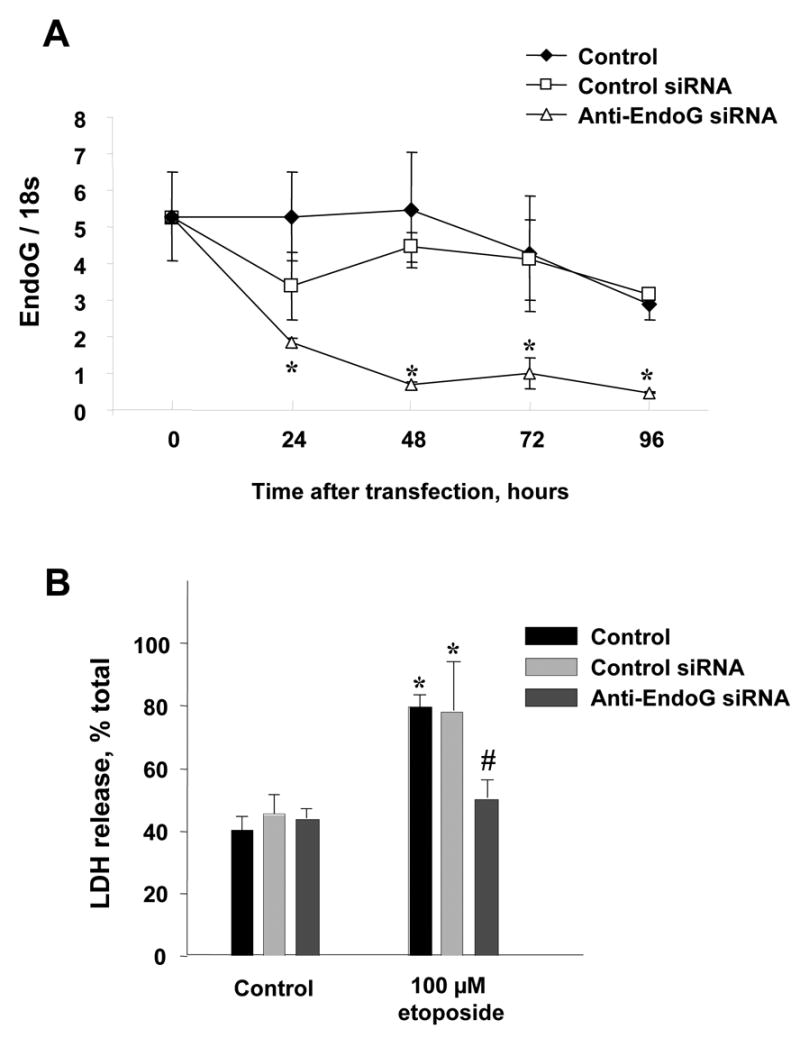

Silencing of EndoG inhibits SK-BR-3 cell death induced by etoposide

RNA interference was applied to further determine the role of EndoG in WDNI breast cancer cell death in a causative manner. SK-BR-3 cells expressing high level of EndoG were transfected with anti-EndoG siRNA or control siRNA as described in Methods. As shown in Fig. 5A, the 72-h transfection was the most effective in silencing of EndoG. Etoposide treatment of the cells after EndoG silencing showed significantly decreased sensitivity to etoposide (Fig. 5B). This experiment directly established EndoG as the endonuclease necessary for the etoposide-induced cell death in these WDNI breast cancer cells.

Fig 5.

Silencing of EndoG protects against the cell death of SK-BR-3 breast cancer cells induced by etoposide. (A) Silencing of EndoG was monitored by real-time PCR as described in Methods at 24, 48, 72 and 96 h after transfection (n = 3 in each group, * - p<0.05 in comparison to untreated or control siRNA-treated cells). (B). SK-BR-3 cells were pretreated with specific anti-EndoG and control siRNA for 72h and then exposed to 100 uM etoposide for 24 hours. Cell death was measured by LDH release assay (n = 4 in each group, * - p<0.05 in comparison to untreated control cells; # - p<0.05 in comparison to etoposide-treated cells).

EndoG expression inversely correlates with the invasiveness of breast cancer cell lines

According to the supplier, the cell lines used in this study were derived from previously characterized tumors. However propagation of the cells might induce phenotypical changes. In order to get a numerical evaluation of the cell line phenotypes and to find out whether EndoG expression is related to differentiation and invasiveness, we measured ER as a marker of differentiation, and vimentin and MMP-13 as markers of invasiveness in all cell lines. The quantitative analysis of these markers using cell ELISA showed that EndoG-expressing WDNI cell lines had a high ER expression in comparison to PDI cell lines (Fig. 6A). Although the ranges of ER in these two groups of cell lines overlap, our measurements confirmed the different level of differentiation between these two groups of cells. The expression of vimentin varied in different WDNI cell lines, but it remained lower compared to that observed in PDI cells. Similarly, the expression of MMP-13 was also different between two groups of cell lines and was lower in WDNI cells than in PDI cells.

Fig 6.

Invasive breast cancer cell lines are EndoG-negative. (A) Comparison of breast cancer markers expression in the used cell lines as measured using cell ELISA. (B) The invasiveness of the cells was determined using the in vitro invasiveness assay, and EndoG was immunostained using anti-EndoG as described in Materials and Methods.

The correlation analysis of the total intracellular endonuclease activity, mainly represented by EndoG, showed that it directly linearly correlated with ER (r=0.7, p<0.05), and inversely correlated with vimentin (r=−0.86, p<0.05) and MMP-13 expression (r=−0.75, p<0.05) as measured by cell ELISA. Similarly, the EndoG expression measured by Western blotting directly correlated with ER (r=0.92, p<0.005), and inversely correlated with vimentin (r=−0.86, p<0.05) and MMP-13 expression (r=−0.93, p<0.05) as measured by cell ELISA.

In order to determine whether the invasive phenotype is saved in these cell lines, the in vitro Matrigel-based invasiveness assay was applied. This assay confirmed the characteristics of the cell lines provided by ATCC, showing that HCC1143, HCC1954 and HCC1395 cells are invasive, while the other cell lines were not (Fig. 6B). The immunostaining analysis using anti-EndoG showed that WDNI cells were EndoG-positive, whereas PDI cells were not, thus confirming the previous observations.

EndoG expression and DNA fragmentation in human breast tumors

In order to study whether the difference in EndoG expression and a corresponding change of endonuclease-mediated apoptosis can be observed in developed breast tumors in vivo, the breast carcinoma tissue microarray was analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. For statistical purposes, only tumor types with 3 or more samples, which included DCIS, MC and DAC were considered. As previously suggested [28], DCIS has emerged as the central lesion against which others were compared. MC has been described as a special type of invasive carcinoma, whereas DAC was designated as carcinoma without specific morphological signs or “not otherwise specified” breast cancer [29]. Our measurements showed significant (p<0.05) decrease of EndoG expression in both invasive carcinoma groups (Fig. 7A and 7B). The highest variation of EndoG expression was found in the DAC group, which can be due to the content of heterogeneous tumors in this group. Importantly, the Spearman ranks correlation analysis of all tumor samples presented in the microarray showed a highly significant correlation between EndoG expression and apoptosis (apoptotic endonuclease-mediated DNA fragmentation) assessed using TUNEL (r=0.42; p=0.001) (Fig 6C).

Fig 7.

EndoG expression and DNA fragmentation correlate with each other and are decreased in invasive human breast tumors. (A, B) Human ductal carcinomas in situ expressed high levels of EndoG, while invasive medullar and ductal carcinomas had significantly decreased expression of EndoG. Apoptotic DNA fragmentation measured by using TUNEL was present in EndoG positive ductal carcinomas in situ. (C) DNA fragmentation correlated with the EndoG expression.

Discussion

The role of cell death endonucleases has not been previously examined in connection with breast cancer cell invasiveness. However, multiple studies demonstrated an association of an invasive phenotype of breast cancer cells with suppressed apoptosis [3–5]. Similar inverse correlations between invasiveness and the ability to produce an apoptotic response after cell injury were described in prostate cancer [30], colon cancer [31, 32], melanoma [33], hepatocellular carcinoma [34] and other types of neoplasia. In most of these studies, apoptosis was often measured by an endonuclease-mediated DNA fragmentation, such as TUNEL [31], in situ end-labeling (ISEL) [30] or a 200 bp-ladder-type DNA fragmentation assays [33].

A causative role of endonucleases in cell death was first suggested more than 20 years ago by Wyllie [35]. Since then, the search for a universal apoptotic endonuclease has led to a general conclusion that in a particular cell the spectrum (availability) of endonucleases, and their regulation determines what enzyme serves in a particular form of cell death [36]. DNases are cytotoxic enzymes due to their ability to induce DNA fragmentation, which interferes with DNA replication and RNA synthesis. Being introduced or overexpressed in the cell, all known apoptotic mammalian DNases [11–15] as well as bacterial endonucleases [37] cause DNA fragmentation and irreversible cell death. DNA in normal cells is protected against endogenous endonucleases by compartmentalization of endonucleases, a high level of chromatin compactization, non-optimal enzymatic conditions in the cell (for example, high concentration of potassium) and by protein inhibitors [8, 16].

The role of endonucleases in the apoptosis of cancer cell death was demonstrated in several studies, however the major endonuclease responsible for breast epithelium and breast cancer cell death was not determined [9, 10]. In the current study, we presented evidence that EndoG is the major endonuclease in breast epithelium and breast cancer cells. We have previously shown that DNase I and EndoG are the most active endonucleases in the kidney [23]. Our data suggest that breast epithelium is very similar to kidney tubular epithelium in this regard. Using DNase I knockout mice, we demonstrated that about 40% of the endonuclease activity in normal breast cells is provided by DNase I, and the rest of it belongs to a Mn-dependent endonuclease similar to EndoG.

EndoG is an endonuclease (DNase/RNase) with a unique site-selectivity, initially attacking poly(dG).poly(dC) sequences in double-stranded DNA, due to which the enzyme got its name [38, 39]. EndoG resides predominantly in the mitochondria, where the enzyme is located in the intermembrane space [40, 41]. Mature active 27 kDa EndoG can be released from mitochondria during apoptosis, relocate to nuclei and cleave nuclear DNA without apparent sequence specificity [13]. The loss of EndoG activity in C.elegans resulted in increased cell survival [8]. It was recently demonstrated that homozygous EndoG−/− knockout mice (129 x C57 background) are not viable, which suggests the great importance of this enzyme for apoptosis during early development [42]. There is a possibility that other factors may affect the role of EndoG in embryogenesis because EndoG−/− knockout mice in C57 background was viable [43]. EndoG has recently been shown to cooperate with DNase I in DNA fragmentation [24]. DNase I is found in all studied species and tissues, however its role in non-digestive tissues (including mammary gland) is still not clear. It is considered a cell death endonuclease because in COS cells transiently transfected with coding sequence cDNA, DNase I induced oligonucleosomal chromatin degradation and apoptotic phenotype [11].

We have compared the activity of endonucleases in seven human breast cancer cell lines different in the level of invasiveness. To ensure that the invasiveness described by ATCC was still present in the cell lines, they were analyzed and confirmed by an in vitro Matrigel-based invasiveness assay. Our general observation was that total endonuclease activity in WDNI cell lines was higher that in PDI cells. Since expression of DNase I determined by zymogram gel electrophoresis was observed only in MCF-7 cells, further studies were continued to determine EndoG expression. Our data demonstrated that EndoG expression vary in a broad range between the used breast cancer cell lines. We found a strong correlation between the expression of EndoG in the cell line and its sensitivity to etoposide. Etoposide is a well known apoptosis inductor, which was shown to induce apoptosis in breast cancer cells [44]. EndoG-positive WDNI cells were more sensitive to etoposide-induced cell death than EndoG-negative PDI cells.

The expression of EndoG measured by Western blotting strongly correlated with the degree of cell differentiation assessed by ER, and it showed inverse correlation with vimentin and MMP-13 expression measured by cell ELISA. These markers are frequently used in breast cancer studies to determine the degree of differentiation and the invasiveness potential of breast cancer cells [45, 46]. An inverse relationship between invasiveness and ER immunoreactivity is usually observed by immunohistochemistry or molecular biology methods [47, 48]. Expression of vimentin alone or its co-expression with keratin or tenascin-C was described to be strongly associated with an increased invasive behavior of breast cancer [49–51]. Thompson et al. [1] found that cells expressing vimentin in the absence of ER(s) are highly invasive. Initial invasion of cancer cells into the host stromal tissue requires the traversing of the basement membrane through the enzymatic degradation of the dense basement membrane collagen matrix. Human matrix metalloproteinase MMP-13 was initially identified in invasive breast cancer and later was found overexpressed in many other invasive tumors [52].

The presented data is the first indication that an endonuclease may be used as a possible marker of cancer cell phenotype. Our in vitro findings suggest that EndoG deficiency observed in PDI cells is a potential new marker for breast cancer progression and a potential predictor of the sensitivity to chemotherapy. Since EndoG is an apoptotic endonuclease, it may be hypothesized that its deficiency plays a role in the survival of invading cancer cells in a new environment. Therefore, EndoG expression might serve as a functional marker of breast cancer progression. Taken together our data suggest that EndoG should be taken into consideration for determining the chemotherapeutic strategy for cancer treatment.

Further studies will be necessary to determine whether EndoG deficiency is pathophysiologically linked with the invasiveness of breast cancer cells. For example, the loss of EndoG in PDI cells may be associated with decreased regulation by estrogens, degradation of the enzyme by metalloproteinases, decrease in the number of mitochondria or presence of defective mitochondria. Another possibility is that EndoG may destroy mRNAs of some proteins in well-differentiated cells by means of its RNase activity. A connection of EndoG and other pro-apoptotic endonucleases with other clinically important characteristics of breast cancer may be studied in the future. For example, since EndoG is responsible for cell breast cancer cell death, it would be interesting to investigate whether estrogen unresponsive breast cancer cells are EndoG-deficient. If this is the case, EndoG deficiency might be used in combination with estrogen responsiveness to determine applied therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by DAMD 17-11-1-0131 grant from the Department of Defense (S.V.S.), VA Merit Review grants (S.V.S., A.G.B.), National Institutes of Health grants 5R03CA114729-02 and 5P01DK58324-04 (A.G.B.) and Tobacco Award (A.G.B.). We thank Dr. Ray Biondo for editorial service.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Thompson EW, Paik S, Brunner N, Sommers CL, Zugmaier G, Clarke R, Shima TB, Torri J, Donahue S, Lippman ME. Association of increased basement membrane invasiveness with absence of estrogen receptor and expression of vimentin in human breast cancer cell lines. J Cell Physiol. 1992;150:534–44. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041500314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer JS, Koehm SL, Hughes JM, Higa E, Wittliff JL, Lagos JA, Manes JL. Bromodeoxyuridine labeling for S-phase measurement in breast carcinoma. Cancer. 1993;71:3531–40. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930601)71:11<3531::aid-cncr2820711112>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim MS, Kang HJ, Moon A. Inhibition of invasion and induction of apoptosis by curcumin in H-ras-transformed MCF10A human breast epithelial cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2001;24:349–54. doi: 10.1007/BF02975105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandez Y, Gu B, Martinez A, Torregrosa A, Sierra A. Inhibition of apoptosis in human breast cancer cells: role in tumor progression to the metastatic state. Int J Cancer. 2002;101:317–26. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mommers EC, van Diest PJ, Leonhart AM, Meijer CJ, Baak JP. Balance of cell proliferation and apoptosis in breast carcinogenesis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;58:163–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1006396103777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vineis P. Cancer as an evolutionary process at the cell level: an epidemiological perspective. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:1–6. doi: 10.1093/carcin/24.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shilkaitis A, Green A, Steele V, Lubet R, Kelloff G, Christov K. Neoplastic transformation of mammary epithelial cells in rats is associated with decreased apoptotic cell death. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:227–33. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hengartner MO. Apoptosis. DNA destroyers. Nature. 2001;412:27–29. doi: 10.1038/35083663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ploski JE, Aplan PD. Characterization of DNA fragmentation events caused by genotoxic and non-genotoxic agents. Mutat Res. 2001;473:169–80. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(00)00147-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shrivastava P, Sodhi A, Ranjan P. Anticancer drug-induced apoptosis in human monocytic leukemic cell line U937 requires activation of endonuclease(s) Anticancer Drugs. 2000;11:39–48. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200001000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polzar B, Peitsch MC, Loos R, Tschopp J, Mannherz HG. Overexpression of deoxyribonuclease I (DNase I) transfected into COS-cells: its distribution during apoptotic cell death. Eur J Cell Biol. 1993;62:397–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krieser RJ, Eastman A. The cloning and expression of human deoxyribonuclease II. A possible role in apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30909–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.30909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li LY, Luo X, Wang X. Endonuclease G is an apoptotic DNase when released from mitochondria. Nature. 2001;412:95–9. doi: 10.1038/35083620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enari M, Sakahira H, Yokoyama H, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Nagata S. A caspase-activated DNase that degrades DNA during apoptosis, and its inhibitor ICAD. Nature. 1998;391:43–50. doi: 10.1038/34112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiokawa D, Ohyama H, Yamada T, Tanuma S. Purification and properties of DNase gamma from apoptotic rat thymocytes. Biochem J. 1997;326:675–81. doi: 10.1042/bj3260675. Pt 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagata S, Nagase H, Kawane K, Mukae N, Fukuyama H. Degradation of chromosomal DNA during apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:108–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Napirei M, Karsunky H, Zevnik B, Stephan H, Mannherz HG, Moroy T. Features of systemic lupus erythematosus in Dnase1-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 2000;25:177–81. doi: 10.1038/76032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Basnakian AG, James SJ. Quantification of 3’OH DNA breaks by random oligonucleotide-primed synthesis (ROPS) assay. DNA Cell Biol. 1996;15:255–62. doi: 10.1089/dna.1996.15.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basnakian AG, Ueda N, Kaushal GP, Mikhailova MV, Shah SV. DNase I-like endonuclease in rat kidney cortex that is activated during ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1000–7. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1341000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–5. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frahm SO, Rudolph P, Dworeck C, Zott B, Heidebrecht H, Steinmann J, Neppert J, Parwaresch R. Immunoenzymatic detection of the new proliferation associated protein p100 by means of a cellular ELISA: specific detection of cells in cell cycle phases S, G2 and M. J Immunol Methods. 1999;223:147–53. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basnakian AG, Kaushal GP, Ueda N, Shah SV. Oxidant mechanisms in toxic acute renal failure. In: Joan B, editor. Toxicology of the Kidney. 3. Tarloff and Lawrence H. Lash; 2005. pp. 499–523. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Widlak P, Li LY, Wang X, Garrard WT. Action of recombinant human apoptotic endonuclease G on naked DNA and chromatin substrates: cooperation with exonuclease and DNase I. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48404–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barry MA, Eastman A. Identification of deoxyribonuclease II as an endonuclease involved in apoptosis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;300:440–50. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howell DP, Krieser RJ, Eastman A, Barry MA. Deoxyribonuclease II is a lysosomal barrier to transfection. Mol Ther. 2003;8:957–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basnakian AG, Apostolov EO, Yin X, Napirei M, Mannherz HG, Shah SV. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity is mediated by deoxyribonuclease I. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:697–702. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004060494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Page DL. Breast lesions, pathology and cancer risk. Breast J 10 Suppl. 2004;1:S3–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2004.101s2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mallon E, Osin P, Nasiri N, Blain I, Howard B, Gusterson B. The basic pathology of human breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2000;5:139–63. doi: 10.1023/a:1026439204849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koch M, de Miguel M, Hofler H, Diaz-Cano SJ. Kinetic profiles of intraepithelial and invasive prostatic neoplasias: the key role of down-regulated apoptosis in tumor progression. Virchows Arch. 2000;436:413–20. doi: 10.1007/s004280050468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sekharam M, Zhao H, Sun M, Fang Q, Zhang Q, Yuan Z, Dan HC, Boulware D, Cheng JQ, Coppola D. Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor enhances invasion and induces resistance to apoptosis of colon cancer cells through the Akt/Bcl-x(L) pathway. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7708–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hashimoto S, Koji T, Kohara N, Kanematsu T, Nakane PK. Frequency of apoptosis relates inversely to invasiveness and metastatic activity in human colorectal cancer. Virchows Arch. 1997;431:241–8. doi: 10.1007/s004280050095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang X, Xu Q, Saiki I. Quercetin inhibits the invasion and mobility of murine melanoma B16-BL6 cells through inducing apoptosis via decreasing Bcl-2 expression. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2000;18:415–21. doi: 10.1023/a:1010960615370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao EH, Hu GD, Li JQ. Relationship between apoptosis and invasive and metastatic potential of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2002;1:574–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wyllie AH. Glucocorticoid-induced thymocyte apoptosis is associated with endogenous endonuclease activation. Nature. 1980;284:555–6. doi: 10.1038/284555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagata S. Apoptotic DNA fragmentation. Exp Cell Res. 2000;256:12–8. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Folle GA, Martinez-Lopez W, Boccardo E, Obe G. Localization of chromosome breakpoints: implication of the chromatin structure and nuclear architecture. Mutat Res. 1998;404:17–26. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(98)00090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruiz-Carrillo A, Renaud J. Endonuclease G: a (dG)n X (dC)n-specific DNase from higher eukaryotes. Embo J. 1987;6:401–7. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb04769.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cote J, Renaud J, Ruiz-Carrillo A. Recognition of (dG)n.(dC)n sequences by endonuclease G. Characterization of the calf thymus nuclease. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:3301–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cote J, Ruiz-Carrillo A. Primers for mitochondrial DNA replication generated by endonuclease G. Science. 1993;261:765–9. doi: 10.1126/science.7688144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohsato T, Ishihara N, Muta T, Umeda S, Ikeda S, Mihara K, Hamasaki N, Kang D. Mammalian mitochondrial endonuclease G. Digestion of R-loops and localization in intermembrane space. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:5765–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang J, Dong M, Li L, Fan Y, Pathre P, Dong J, Lou D, Wells JM, Olivares-Villagomez D, Van Kaer L, Wang X, Xu M. Endonuclease G is required for early embryogenesis and normal apoptosis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15782–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2636393100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Irvine RA, Adachi N, Shibata DK, Cassell GD, Yu K, Karanjawala ZE, Hsieh CL, Lieber MR. Generation and characterization of endonuclease G null mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:294–302. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.294-302.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang XH, Sladek TL, Liu X, Butler BR, Froelich CJ, Thor AD. Reconstitution of caspase 3 sensitizes MCF-7 breast cancer cells to doxorubicin- and etoposide-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:348–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Z, Brattain MG, Appert H. Differential display of reticulocalbin in the highly invasive cell line, MDA-MB-435, versus the poorly invasive cell line, MCF-7. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;231:283–9. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zajchowski DA, Bartholdi MF, Gong Y, Webster L, Liu HL, Munishkin A, Beauheim C, Harvey S, Ethier SP, Johnson PH. Identification of gene expression profiles that predict the aggressive behavior of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5168–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oyama T, Take H, Hikino T, Iino Y, Nakajima T. Immunohistochemical expression of metallothionein in invasive breast cancer in relation to proliferative activity, histology and prognosis. Oncology. 1996;53:112–7. doi: 10.1159/000227546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kun Y, How LC, Hoon TP, Bajic VB, Lam TS, Aggarwal A, Sze HG, Bok WS, Yin WC, Tan P. Classifying the estrogen receptor status of breast cancers by expression profiles reveals a poor prognosis subpopulation exhibiting high expression of the ERBB2 receptor. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:3245–58. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hendrix MJ, Seftor EA, Seftor RE, Trevor KT. Experimental co-expression of vimentin and keratin intermediate filaments in human breast cancer cells results in phenotypic interconversion and increased invasive behavior. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:483–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thomas PA, Kirschmann DA, Cerhan JR, Folberg R, Seftor EA, Sellers TA, Hendrix MJ. Association between keratin and vimentin expression, malignant phenotype, and survival in postmenopausal breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2698–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dandachi N, Hauser-Kronberger C, More E, Wiesener B, Hacker GW, Dietze O, Wirl G. Co-expression of tenascin-C and vimentin in human breast cancer cells indicates phenotypic transdifferentiation during tumour progression: correlation with histopathological parameters, hormone receptors, and oncoproteins. J Pathol. 2001;193:181–9. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH752>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Freije JM, Diez-Itza I, Balbin M, Sanchez LM, Blasco R, Tolivia J, Lopez-Otin C. Molecular cloning and expression of collagenase-3, a novel human matrix metalloproteinase produced by breast carcinomas. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16766–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]