This discussion is in response to a letter-to-the editor in the form of a ‘Commentary’ by Bussieres, Ammendolia, Peterson, and Taylor1 concerning our original commentary: ‘On “phantom risks” associated with diagnostic ionizing radiation: evidence in support of revising radiography standards and regulations in chiropractic,2 published in the December 2005 issue of this journal.

Bussieres et al.1 have expressed that our original commentary lacked credibility, while they claimed that: 1) we have a vested financial interest in promoting routine and follow-up x-rays; 2) we provided a biased and unscientific evaluation of the evidence; 3) there is “no convincing evidence that the use of radiography for spinal biomechanical assessment (other than for scoliosis) is of any therapeutic value”; and 4) ‘unnecessary’ x-rays are associated with high health care costs.

Ad Hominem Attacks

First, we will address their1 “Ad Hominem” attacks on us. They referred to our paper as “self serving”, “professionally irresponsible”, and having a “vested financial interest”. An Ad Hominem attack has no place in a scientific debate. In fact, the Ad Hominem attack is one of the fallacies in scientific debates; instead of critiquing the science, attack the character of the individual.3 According to Stein,3 when an individual resorts to an Ad Hominem attack, they have lost credibility. Normally, we would ignore such insults, however, we note only two of the four authors (Harrisons) have any financial gain from CBP technique (by seminar attendance) – but how do doctors, in different States/Provinces/Countries, x-raying their own patients, transcribe the knowledge gained about spinal health into a financial benefit for any of our authors?

Biased and Unscientific Evaluation of the Evidence

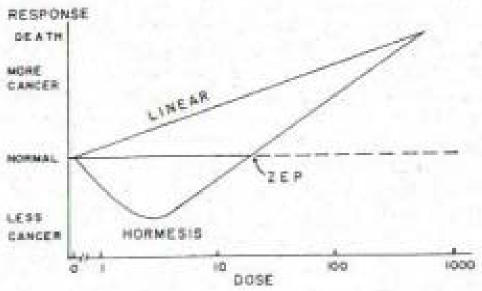

Second, Bussieres et al.1 claimed that we presented a biased and unscientific evaluation of the evidence on cancer risks from exposure to ionizing radiation. We believe, while being brief, we presented the facts. We presented a review of 7 studies of human exposures to low-level radiation that resulted in health benefits for these populations.2 So, in support of our previous article, we will expand on our evaluation of the evidence. For our discussion, we direct the reader to Figure 1 as a visual representation of the Linear-No-Threshold Model (LNT) and the Radiation Hormesis Model of cancer risks from exposure to ionizing radiation.

Figure 1.

“Linear” indicates the LNT Model, which is a linear extrapolation from the high dose (dose-rate) of atomic bombs dropped on Japan, drawn linearly down to zero. This model assumes that any exposure has a cancer risk, and the greater the exposure, the greater the cancer risk. “Hormesis” is the quadratic shaped curve (U-shaped curve), where between zero and the zero equivalent point (ZEP), there is less risk of cancer or a ‘benefit’. However, doses greater than the ZEP (a threshold) indicate a near linear increased risk of cancer with increasing doses. (adapted from Luckey, 1991 and Hiserodt, 2005).4,5

Controversy in the BEIR VII Conclusions

Bussieres et al.1 fall prey to a typical argument on cancer risks by citing references that neglect Hormesis evidence. They1 cited the 2005 BEIR report6 and a few other references used in the BEIR report.7–10 We had read parts of the long BEIR report and noted that it often made its claims while assuming the LNT model. In fact, what Bussieres et al.1 failed to mention is that, in 2005, Aurengo et al.11 compared the Reports by the French Academy of Sciences and the French Academy of Medicine, both of which reached the same opposite conclusion to BEIR VII.

Aurengo et al.11 found that the BEIR report neglected hormesis evidence and neglected negative analyses of the studies that were cited. Also we note that the BEIR Report has not been officially issued yet, (only a preliminary draft on their web site) and is still subject to change. In contrast, the unanimous report by the French Academy of Sciences and National Academy of Medicine (2005) stated:

“In conclusion, this report doubts the validity of using the LNT in the evaluation of the carcinogenic risk of low doses (<100mSv) and even more for very low doses (<10mSv). … the use of LNT in the low dose or dose rate range is not consistent with the current radiobiological knowledge; LNT cannot be used without challenge … for very low doses (<10mSv). … The eventual risks in the dose range of radiological examinations (0.1 to 5 mSv, up to 20mSv for some examinations) must be estimated taking into account radio-biological and experimental data. An empirical relationship which is valid for doses higher than 200 mSv may lead to an overestimation of risk associated with doses one hundredfold lower and this overestimation could discourage patients from undergoing useful examinations and introduce a bias in radioprotection measures against very low doses (<10 mSv).”11

Cohen’s Outline

In preparation for this rebuttal, we contacted one of the leading authorities on radiation exposure risks, Dr. B. L. Cohen,12–22 University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA. What follows is the outline that Cohen provided to us:23

Problems with the Basis for the Linear-No-Threshold Theory

Direct Experimental Challenges to the Basis for LNT

Effects of Low-Level Radiation on Biological Defense Mechanisms

Stimulation of the Immune System

Cancer Risks vs Dose in Animal Experiments

-

Cancer Risks vs Dose in Human Experiments

Critique of Data Frequently Cited Supportive of LNT

Data Contradictory to LNT

1. Problems with the Basis for LNT

The LNT model is theoretical and simple: A single particle of radiation hitting a single DNA molecule in a single cell nucleus of the human body can initiate cancer. Therefore cancer initiation probability is proportional to the number of events, which is proportional to the number of particles of radiation, which is proportional to the dose. Thus the LNT theory is “the risk is proportional to the dose”.23 The problem with this simple theory is that other factors affect cancer risk, i.e., human bodies have biological defense mechanisms that prevent the vast majority of radiation events from becoming a cancer.24

There are several defense mechanisms: (1) The most important cause of DNA injury is corrosive chemicals termed reactive oxygen species (ROS) and low-level radiation has been shown to stimulate the scavenging processes to eliminate these from cells;25 (2) There is abundant evidence that low-level radiation stimulates the immune system, while high levels/doses depress the immune response;26 (3) Radiation can alter cell timing, i.e., the time before the next cell division/mitosis and low-levels of radiation increase this time and allow for more possible DNA repair; (4) Low dose hypersensitivity and increased radiation radioresistance are affected by low-level radiation;27 and (5) It is now recognized that tissue response, whole organ response, and organism response, rather than just single cellular response, must be considered.11

There is another obvious failure of the original LNT model. The theory predicts that the number of initiating events is roughly proportional to the mass of the animal being irradiated. However, research has shown that the cancer risk for a given radiation field is similar for a 30 gram mouse and a 70,000 gram human.26

Interestingly, validity of the LNT model is based on double strand breaks (DSB) in DNA molecules. However, Feinendegen26 estimated that ROS causes about 0.1 DSB per cell per day, whereas 100 mSv (10 rem) of radiation causes about 4 DSB per cell. Using this information, a 100 mSv dose of radiation would increase the lifetime risk of cancer (28,000 days × 0.1 DSB/day) by only about 0.14% (4/28,000), but the LNT model predicts 7 times that much at 1%.

2. Direct Experimental Challenges to the Basis for LNT

A direct failure of the basis for the LNT model is derived from microarray studies, which determine what genes are up-regulated and what genes are down-regulated by radiation. It was discovered that generally different sets of genes are affected by low-level radiation as compared to high-level doses. In 2003, Yin et al.28 used doses of 0.1 Sv and 2.0 Sv applied to mouse brain. The 0.1 Sv dose induced expression of protective and repair genes, while the 2.0 Sv dose did not.

A similar study on human fibroblast cells was conducted in 2002 by Golder-Novoselsky et al.29 Using doses of 0.02 Sv and 0.5 Sv, they discovered that the 0.02 Sv dose induced stress response genes, while the 0.5 Sv dose did not. Several other microarray studies have demonstrated that high radiation doses, which serve as the “calibration” for LNT, are not equivalent to adding an accumulation of low radiation doses.30

In fact, in 2001, Tanooka31 studied tumor induction by irradiating the skin of mice throughout their lifetimes. For irradiation rates of 1.5 Gy/week, 2.2 Gy/week, and 3 Gy/week, the percentage of mice that developed tumors was 0%, 35%, and 100%, respectively. This31 data demonstrated a clear threshold response directly in conflict with predictions of the LNT model.

3. Effects of Low-Level Radiation on Biological Defense Mechanisms

In 1994, the United Nations Scientific Committee on Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) report32 defined “adaptive response” as a type of biological defense mechanism that is characterized by sequent protection to stresses after an initial exposure of a stress (like radiation) to a cell. For radiation experiments, this is studied by exposing cells to low-doses to prime the adaptive response and then later exposing it to a high radiation “challenge dose” to see what happens. There have been several experiments in this topic,33–42 and we report on just a few of these.33–35

In 1990, Cai and Liu33 exposed mouse cells in 2 different ways: (1) a high dose of 65 cGy (65 rad), and (2) a low-dose of 0.2 cGy before the high-dose of 65 cGy. The number of chromosome aberrations reduced in the second group compared to the first group was 38% bone marrow cell aberrations reduced to 19.5% and 12.6% spermatocyte aberrations reduced to 8.4 %.

In 1992, Shadley and Dai34 irradiated human lymphocyte cells, some with high doses and some with a low-dose a few hours before a high-dose. The number of chromosome aberrations caused by a high-dose was substantially reduced when a preliminary low-dose was given first.

In 2001, Ghiassinejad et al.35 studied this effect in humans. In Iran, residents of a high background radiation area (1 cGy/year) were compared to residents in a normal background radiation area (0.1 cGy/yea). When lymphocytes, taken from these groups, were exposed to 1.5 Gy (150 rad), the percentages of aberrations were 0.098 for the high background area versus 0.176 (about double) for the low background area. The radiation in the high background area protected its residents from the 1.5 Gy dose.

4. Stimulation of the Immune System

The effects of low-level radiation on the immune system are important since the immune system is responsible for destroying cells with DNA damage. Low doses of radiation exposure cause stimulation of the immune system while high doses reduce immune activity.43–45

Contrary to expectations from the basic assumption of the LNT model (cancer risks depends only on total dose), effects on the immune system are quite different for the same total dose given at a low dose rate (summation of several small doses) versus one high dose rate, i.e., at low dose rates the immune system is stimulated, while at high doses, cancers are caused.46–50

5. Cancer Risks vs Dose (Animal Experiments)

To test the validity of the LNT model, there have been numerous direct experiments of cancer risk versus dose, with animals exposed to various radiation doses. In 1979, Ullrich and Storer51 reported that exposed animals lived up to 40% longer than controls. In a series of animal studies in the 1950s and 1960s, review articles by Finkel and Biskis52–54 reported, with high statistical significance, that the LNT model over-estimated the cancer risks from low-level radiation exposures and they reported a threshold not a linear response.

In a 2001 review of over 100 animal radiation experiments, Duport55 reported on studies involving over 85,000 exposed animals and 45,000 controls, with a total of 60,000 cancers in exposed animals and 12,000 cancers in control animals. In cases where cancers were observed in controls receiving low doses, either no effect or an apparent reduction in cancer risk was observed in 40% of the data sets for neutron exposure, 50% of the data sets for x-ray exposure, 53% of the data sets for gamma rays exposure, and 61% of the data sets for alpha particles exposure.

6. Cancer Risks vs Dose (Human Experiments):

A. Critique of Data Frequently Cited in Support of LNT

The principle data cited and used to support the LNT model are those for solid tumors (all cancers except leukemia) in the survivors of the Japanese atomic bomb explosions. Pierce’s 1996 paper56 reported data from 1945–1990. By ignoring the error bars, supporters of the LNT model claim that the data suggests an approximate linear relationship with intercept near zero. But there is no data that gives statistical significant indication of excess cancers for radiation doses below 25 cSv.57 Leukemia data from Japanese A-bomb survivors strongly suggest a threshold above 20 cSv and the contradiction to the LNT model is recognized by the author.57 In 1998, Cohen58 used the three lowest dose points in the Japanese data (0–20 cSv) to show that the slope of the dose-response curve has a 20% probability of being negative (i.e., Hormesis = risk decreasing with increasing dose).

The next often cited evidence, by supporters of the LNT model, is the International Association for Research on Cancer (IARC) studies on monitored radiation workers. In 1995, Cardis et al.59 reported on 95,673 monitored radiation workers in 3 countries and in a follow-up study by the same authors in 2005,60 they reported on 407,000 monitored workers in 154 facilities in 15 countries. In the first study, for all cancers except leukemia (there were 3,830 deaths, but no excess over the number expected from the general population), the risks were reported as −0.07/Sv with 90% confidence limits of (−04,+0.3), i.e., there is NO support for LNT from this data! However, for leukemia (146 deaths), they reported a positive correlation, but their data had no indication of any excess cancers (risks) below 40 cSv. Most importantly, these authors discarded 3/7 of their data points when observed/expected was less than unity. In fact, Cohen23 noted that (1) no information on such confounding factors as smoking was given, (2) if data from just one of the 15 countries was eliminated (Canada), the appearing excess is no longer statistically different from zero, (3) the authors did not consider non-occupational exposure (natural background radiation) and if they had, they would have noticed that their excess “signal” was much smaller than the “noise” from background radiation.

Often critics of Radiation Hormesis use the “Healthy Worker effect” to discredit what is found. When studying mortality rates for employed workers compared to the general population, it is found that workers have lower mortality rates. In Sweden in 1999, Gridley61 compared 545,000 employed women to 1,600,000 unemployed women. He reported that the cancer incidence rate was slightly higher for employed women (1.05 ± 0.01). This eliminated the claims of the “Healthy Worker effect”. For an example of improper use of this effect, in 2005 Rogel62 studied 22,000 monitored workers in the French nuclear power industry. The cancer mortality rate was only 58% of the general French population. Instead of concluding a Hormesis effect, Rogel claimed that this large difference was due to the “healthy worker effect”.62

B. Data Contradictory to LNT

There is much data contradictory to the LNT model. There are multiple human studies which show a radiation Hormesis effect.16,22,64–72

For breast cancer in Canadian women, Miller63 reported a decrease risk with increasing dose up to 25 cSV. Howe64 (for lung cancer in Canadian women) and Davis65 (for 10,000 people in Massachusetts) separately reported a decrease in cancers in the low-dose region up to 100 cSv. There is a difference between lung cancer rates in Japanese A-bomb survivors and the data from Howe and Davis: the Japanese survivors show a much higher risk at all doses. This indicates that one must not accept A-bomb survivor data (one large dose) to predict risks from low-dose rates where low-level doses are summed. It is known that risks from summing low doses (such as spinal radiography use in chiropractic) does not equal the risks from one large dose (Tubiana).30

Kostyuchenko66 reported on a follow-up of 7,852 villagers exposed in the 1957 radioactive storage facility explosion in Russia. The cancer mortality rate was much lower in these villagers than in unexposed villagers in the same area supporting a hormetic effect. However, the exposure of the workers directly at the facility was quite high in one dose and these workers were found to have an increase in cancers indicating a dose threshold for increase cancers (Koshurnikova 2002).67

In 1997, Sakamoto68 reported on radiation treatments in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Patient groups were randomly separated into radiation treatment and non-radiation treatment. After 9 years, 50% of the control group died but only 16% of the irradiated group died.

The conclusion from Cohen’s outline23 is that the LNT theory fails badly in the low dose region. It grossly overestimates the cancer risks from low-level radiation. The cancer risk from the vast majority of normally encountered radiation exposures (background radiation, medical x-rays, etc.) is much lower than estimates given by supporters of the LNT model, and it may well be zero or even negative.

Critique of Bussieres et al.1 Cancer Risk References

As previously discussed, Aurengo11 reported on two groups who came to the opposite conclusions compared to the 2005 BEIR report.6

In their risks argument, Bussieres et al.1 passionately present (their table 1) the number of estimated cancer deaths per year as calculated from known x-ray usage in the Berrington de Gonzalez study.8 This study8 relied solely on the LNT model and has been critcized by many for several reasons. First, as several critics noted73–76 and for which the authors8 admitted in their reply,77 they failed to weigh the benefits of diagnostic x-rays in their study, which only guarantees an overestimate of death calculations. Another criticism was their assumption of the LNT to make their cancer death estimations. Tubiana et al.74 pointed out the “speculative nature” of the LNT hypothesis, and along with Simmons,78 noted that the LNT is only compatible with exposures greater than 200mSv ( significantly more radiation than any medical x-rays).

Another criticism is that the Japanese survival data has significant limitations to extrapolate its use for x-ray risk estimates from γ rays. The Japanese exposure was a one time high dose, which is entirely different from accumulated small dose rates. Herzog and Rieger73 note that this data will overestimate cancer risk because the Japanese were exposed to γ rays from bombs, a different energy spectrum than x-rays, but also the additional exposures of β radiation, radionuclides emitting β, and high-energy α radiation from contaminated water, food, and dust.

Yet another criticism of the study was that there was no mention of the complexity and effectiveness of the human cell’s defenses against ionizing radiation. Tubiana et al.74 noted there are hundreds of enzymes devoted to protect a cell from these effects and that “there is no single defense mechanism but a variety,… an adaptive effect exists and a hormetic effect has even been seen in more than half of experimental studies after low or moderate doses.”79–80 “Extrapolation from high doses to low doses with LNT is unlikely to be able to assess the risks accurately.”74

For Bussieres et al.1 to use this study as ‘evidence’ for rationale for x-ray guidelines is dubious. In fact, without mentioning the scientific peer concerns surrounding the study,73–76,78 (it is readily observed on pub-med that a number of letters to the editor were published) we can only conclude that they1 are the ones presenting a ‘biased’ evaluation of the evidence.

No Convincing Evidence for the Use of Radiography for Spinal Assessment

Next, we arrive at Bussieres et al.1 third complaint about our original article. Using 3 references, (Ammendolia et al.,81 Mootz et al.,82 Haas et al.83) Bussieres et al.1 state x-rays are not useful due to lack of clinical relevance. The Ammendolia article81 is a questionnaire study with a focused group interview about clinicians’ opinions and practices regarding acute low back pain only. This paper disregarded an entire body of evidence in opposition to the papers’ conclusions that was not addressed.84

Further, as in their commentary at hand,1 medical ‘diagnostic red flag only’ references are used for a chiropractic argument against x-ray usage. That is, chiropractic doctors differ fundamentally in assessment, diagnosis, and treatment than their medical counterparts. Therefore, Medical references apply to the profession of drugs and surgery, NOT chiropractic, which uses physical forces applied to spines. Not only is the spinal structure intricately examined by chiropractors but as Mootz et al.82 states: “identifying contraindications to … manipulation, however, is a purpose that belongs only to practitioners of manual therapies, especially DCs.”

Bussieres et al.1 commit a common error by citing Haas et al.83 without acknowledging that this is the middle paper of a 3-part debate.85.86 The Haas reference83 has been clearly rebutted.86

The Mootz et al.82 review is a decade old, and even they stated “using plain film imaging, single studies result in relatively insignificant radiation dosages and expense.” At that time, (1997) Mootz et al.82 suggested that changes in patient misalignment had yet to be determined to impact clinical progress. Despite even being arguable at that time, in the following decade, there has been a variety of good quality, biomechanical and outcome studies defining this relationship published by the CBP group.87–96 In fact, in the recent ICA X-ray Guidelines (PCCRP), there are hundreds of Chiropractic outcome studies cited.97

Furthermore, Bussieres et al.1 failed to acknowledge the recent randomized trial by Khorshid et al.98 where a clinically and statistically significant improvement in autistic children treated with upper cervical technique (using x-rays) was found compared to those treated with standard full spine technique (no x-rays).

Previous authors have stated that guidelines for chiropractic clinicians’ and manual therapists’ utilization of x-ray should be different from those of a medical practitioner who does not use spinal adjustments/forces and rehabilitation procedures as treatment for spinal subluxations.99–101 In studies specifically considering the role of chiropractic treatment interventions, spinal radiographic views indicate that between 66%–91% of patients can have significant abnormalities affecting treatment:102–104 33% can have relative contraindications and 14% can have absolute contraindications to certain types of chiropractic adjustment procedures.104

Radiography Is Not Cost Effective

Bussieres et al.1 mention that patients receiving radiography are more satisfied with care, but then discard this finding in favor of a ‘cost reducing model of health care’. We feel it is important to present this information in proper context.

For example, in a randomized trial comparing the intervention of lumbar radiography to no radiography in patients with at least 6 weeks duration of low back pain, Kendrick et al.105,106 found no differences in outcomes between the groups. Problematically, the intervention used for treatment did not specifically address any structural spinal displacements as chiropractic clinicians would readily apply. Importantly, patients receiving radiography were more satisfied with the care they received.105,106 Furthermore, patients allocated to a preference group, where the decision to receive lumbar radiography was made by them, achieved clinically significant improved outcomes compared to those randomized to a non-radiography or a radiography group.106

Thus, undercutting patient choice by ‘red flag’ only guidelines, as Bussieres et al.1 would have us do for chiropractic practice, limits a patient’s right to choose and may impair or slow recovery. However, just as importantly, we caution Bussieres et al.1 for applying results from clinical studies with pharmacology and PT treatments to Chiropractic situations where the treatments are vastly different (physical forces applied to spinal structures).

While cost-effectiveness analysis may favor limited x-ray utilization in a volume 3rd party payer scenario where maximization of profits is the goal,107 in the individual patient, case specific circumstances can lead to a different conclusion. It is our perspective that, in chiropractic clinical practice, the needs of the one outweigh the needs of the many or the managed care organization; our duty is to identify the spinal problem of the individual and develop solution strategies where possible.

Lastly, there is an expectation by the consumer to have a thorough spinal evaluation when seeing a DC for a health problem and this includes an x-ray evaluation for alignment of the spine and the state of health of the spine.108

Conclusion

In summary, Bussieres et al.’s1 Ad Hominem attacks on us and their main arguments against routine use of radiography in common practice, radiation risks, and lack of clinical usefulness are without scientific support. In fact, Luckey stated, “for every thousand cancer mortalities predicted by the linear models (LNT), there will be a thousand decreased cancer mortalities and ten thousand persons with improved quality of life.” 4

References

- 1.Bussieres AE, Ammendolia C, Peterson C, Taylor JAM. Ionizing radiation exposure – more good than harm? The preponderance of evidence does not support abandoning current standards and regulations. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2006;50(2):103–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oakley PA, Harrison DD, Harrison DE, Haas JW. On “phantom risks” associated with diagnostic radiation: evidence in support of revising radiography standards and regulations in chiropractic. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2005;49(4):264–269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stein F. Anatomy of Research in Allied Health. New York: John Wiley & Sons. 1976, pg 45.

- 4.Luckey TD. Radiation hormesis. Boca Raton: CRC Press, Boston, 1991.

- 5.Hiserodt E. Underexposed: What if radiation is actually good for you? Laissez Faire Books, Little Rock, Arkansas, 2005.

- 6.Committee to assess health risks from exposure to low levels of ionizing radiation. Health risks from exposure to low levels of ionizing radiation: BEIR VII Phase 2. National Research Council. Washington DC: National Academies Press, 2005. [PubMed]

- 7.Evans JS, Wennberg JE, McNeil BJ. The influence of diagnostic radiography on the incidence of breast cancer and leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1986;315(13):810–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198609253151306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berrington de Gonzalez A, Darby S. Risks of cancer from diagnostic x-rays: estimates for the UK and 14 other countries. Lancet. 2004;363:345–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15433-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Assesssment and management of cancer risks from radiological and chemical hazards 1998 Health Canada, Atomic Energy Control Board ISBN: 0-662-82719-8.

- 10.Shiralkar S, Rennie A, Snow M, Galland RB, Lewis MH, Gower-Thomas K. Doctors' knowledge of radiation exposure: questionnaire study. BMJ. 2003;327:371–72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7411.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aurengo, A. et al. (2005) Dose-effect relationship and estimation of the carcinogenic effects of low dose ionizing radiation, Available at http://cnts.wpi.edu/rsh/docs/FrenchAcads-EN-FINAL.pdf

- 12.Cohen BL, Lee IS. A catalog of risks. Health Physics. 1979;36:707–722. doi: 10.1097/00004032-197906000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen BL. Limitations and problems in deriving risk estimates for low-level radiation exposures. J Biol Med. 1981;54:329–338. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen BL. Catalog of risks extended and updated. Health Physics. 1991;61(3):317–335. doi: 10.1097/00004032-199109000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen BL. Dose-response relationship for radiation carcinogenesis in the low-dose region. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1994;66:71–75. doi: 10.1007/BF00383360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen BL. Test of the linear-no threshold theory of radiation carcinogenesis for inhaled radon decay products. Health Phys. 1995;68:157–174. doi: 10.1097/00004032-199502000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen BL. How dangerous is low level radiation? Risk Anal. 1995;15:645–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1995.tb01336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen BL. Problems in the radon vs. lung cancer test of the linear no-threshold theory and a procedure for resolving them. Health Phys. 1997;72:623–628. doi: 10.1097/00004032-199704000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen BL. Updates and extensions to tests of the linear no-threshold theory. Technology. 2000;7:657–672. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen BL. The cancer risk from low level radiation: a review of recent evidence. Med Sent. 2000;5:128–131. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen BL. Cancer risk from low-level radiation. Am J Radiol. 2002;179:1137–1143. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.5.1791137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen BL. Test of the linear-no-threshold theory: rationale for procedures. Nonlinearity in Biology, Toxicology, and medicine. 2005;3:261–82. doi: 10.2203/dose-response.003.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen BL. Outline of a Radiation Handbook. Private Communication, June 2006.

- 24.Pollycove M, Feinendagen L. Biologic responses to low doses of ionizing radiation: detriment vs hormesis; Part 1. J Nuclear Med. 2001;42:17N–27N. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kondo S. Health Effects of Low Level Radiation. Madison, WI; Medical Physics Publishing, 1993; pp 85–89.

- 26.Feinendegen LE. Evidence for beneficial low level radiation effects and radiation hormesis. Brit J Radiol. 2005;78:3–7. doi: 10.1259/bjr/63353075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonner WN. Phenomena leading to cell survival values which deviate from linear-quadratic models. Mutation Res. 2004;568:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin E, et al. Gene expression changes in mouse brain after exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation. Int J Radiat Biol. 2005;79:759–775. doi: 10.1080/09553000310001610961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Golder-Novoselsky, E., Ding, LH, Chen,F, and Chen,DJ. Radiation response in HSF cDNA microarray analysis, DOE Low dose radiation research program, Workshop III, U.S. Dept. of Energy, Washington, DC, 2002.

- 30.Tubiana M, Aurengo A. Dose effect relationship and estimation of the carcinogenic effects of low doses of ionizing radiation. Int J Low Radiat. 2005;2:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanooka H. Threshold dose-response in radiation carcinogenesis: an approach from chronic beta-irradiation experiments and a review of non-tumor doses. Int J Radiat Biol. 2001;77:541–551. doi: 10.1080/09553000110034612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.UNSCEAR (United Nations Scientific Committee on Effects of Atomic Radiation). Report to the General Assembly, Annex B: Adaptive Response. United Nations, New York, 1994.

- 33.Cai L, Liu SZ. Induction of cytogenic adaptive response of somatic and germ cells in vivo and in vitro by low dose X-irradiation. Int J Radiat Biol. 1990;58:187–194. doi: 10.1080/09553009014551541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shadley JD, Dai GQ. Cytogenic and survival adaptive responses in G-1 phase human lymphocytes. Mutat Res. 1992;265:273–281. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(92)90056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghiassi-nejad M, Mortazavi SMJ, Beitollahi M, Cameron JR, et al. Very high background radiation areas of Ramsar, Iran: preliminary biological studies and possible implications. Health Phys. 2002;82:87–93. doi: 10.1097/00004032-200201000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coleman MA, et al. Low dose irradiation alters the transcript profiles of human lymphoblastoid cells including genes associated with cytogenic radioadaptive response. Radiat Res. 2005;164:369–382. doi: 10.1667/rr3356.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelsey KT, Memisoglu A, Frenkel A, Liber HL. Human lymphocytes exposed to low doses of X-rays are less susceptible to radiation induced mutagenesis. Mutat Res. 1991;263:197–201. doi: 10.1016/0165-7992(91)90001-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fritz-Niggli H, Schaeppi-Buechi C. Adaptive response to dominant lethality of mature and immature oocytes of D. Melanogaster to low doses of ionizing radiation: effects in repair-proficient and repair deficient strains. Int J Radiat Biol. 1991;59:175–184. doi: 10.1080/09553009114550161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Le XC, Xing JZ, Lee J, Leadon SA, Weinfeld M. Inducible repair of thymine glycol detected by an ultrasensitive assay for DNA damage. Science. 1998;280:1066–1069. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5366.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Azzam EI, de Toledo SM, Raaphorst GP, Mitchel REJ. Low dose ionizing radiation decreases the frequency of neoplastic transformation to a level below spontaneous rate in C3H 10T1/2 cells. Radiat Res. 1996;146:369–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Redpath JL, Antoniono RJ. Induction of a rapid response against spontaneous neoplastic transformation in vitro by low dose gamma radiation. Rad Res. 1998;149:517–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yukawa O, et al. Induction of radical scavenging ability and suppression of lipid peroxidation in rat liver microsomes following whole body low dose X-irradiation. J Radiat Biol. 2005;81:681–688. doi: 10.1080/09553000500401445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu SJ. Multilevel mechanisms of stimulatory effect of low dose radiation on immunity. In: Sugahara T, Sagan LA, Aoyama T, ed. Low Dose Irradiation and Biological Defense Mechanisms. Amsterdam, Elsevier Science, 1992: pp 225–232.

- 44.Makinodan T. Cellular and sub-cellular alteration in immune cells induced by chronic intermittent exposure in vivo to very low dose of ionizing radiation and its ameliorating effects on progression of autoimmune disease and mammary tumor growth. In: Sugahara T, Sagan LA, Aoyama T, ed. Low Dose Irradiation and Biological Defense Mechanisms, Amsterdam, Elsevier Science, 1992: pp. 233–237.

- 45.Liu SZ. Non-linear dose-response relationship in the immune system following exposure to ionizing radiation: mechanisms and implications. Nonlinearity in Biology, Toxicology, and Medicine. 2003;1:71–92. doi: 10.1080/15401420390844483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ina Y, Sakai K. Activation of immunological network by chronic low dose rate irradiation in wild type mouse strains: analysis of immune cell populations and surface molecules. Int J Radiat Biol. 2005;81:721–729. doi: 10.1080/09553000500519808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ina Y, et al. Suppression of thymic lymphoma induction by life-long low dose rate irradiation accompanied by immune activation of C57BL/6 mice. Radiat Res. 2005;163:153–158. doi: 10.1667/rr3289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sakamoto K, Myogin M, Hosoi Y, et al. Fundamental and clinical studied on cancer control with total and upper half body irradiation. J Jpn Soc Ther Radiol Oncol. 1997;9:161–175. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hashimoto S, Shirato H, Hosokawa M, et al. The suppression of metastases and the change in host immune response after low-dose total body irradiation in tumor bearing rats. Radiat Res. 1999;151:717–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Makinodan T, James SJ. T cell potentiation by low dose ionizing radiation: possible mechanisms. Health Phys. 1990;59:29–34. doi: 10.1097/00004032-199007000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ullrich RL, Storer JB. Influence of gamma radiation on the development of neoplastic diseases in mice: II solid tumors. Radiat Res. 1979;80:317–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Finkel MP, Biskis BO. Toxicity of Plutonium in mice. Health Phys. 1962;8:565–579. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Finkel MP, Biskis BO. 1968;Prog Exp Tumor Res10:72ff. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Finkel, MP, Biskis BO. Pathological consequences of radiostrontium administered to fetal and infant dogs. Radiation biology of the fetal and juvenile mammal, AEC Symposium Series, vol. 17, Proceedings of the 9th Hanford Biology Symposium, 1969: pp. 543–565.

- 55.Duport P. A data base of cancer induction by low-dose radiation in mammals: overview and initial observations, Second Conference of the World Council of Nuclear Workers (WUNOC), Dublin, 2001.

- 56.Pierce DA, Shimizu Y, Preston DL, Vaeth M, Mabuchi K. Studies of the mortality of atomic bomb survivors, Report 12, Part 1, Cancer: 1950–1990. Radiat Res. 1996;146:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heidenreich WF, Paretzke HG, Jacob B. No evidence for increased tumor risk below 200 mSv in the atomic bomb survivor data. Radiat Envoron Biophys. 1997;36:205–207. doi: 10.1007/s004110050073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cohen BL. The cancer risk from low level radiation. Radiat Res. 1998;149:525–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cardis E, et al. Effects of low dose and low dose rates of external ionizing radiation: Cancer mortality among nuclear industry workers in three countries. Radiat Res. 1995;142:117–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cardis E, et al. Risk of cancer after low doses of ionizing radiation: retrospective cohort study in 15 countries. Brit Med J. 2005;331:77–90. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38499.599861.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gridley G, et al. Is there a healthy worker effect for cancer incidence among women in Sweden? Am J Ind Med. 1999;36:193–199. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199907)36:1<193::aid-ajim27>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rogel A, et al. Mortality of workers exposed to ionizing radiation at the French National Electricity company. Am J Ind Med. 2005;47:72–82. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miller RC, Randers-Pehrson G, Geard CR, Hall EJ, Brenner DJ. The oncogenic transforming potential of the passage of single alpha particles through mammalian cell nuclei. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:19–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Howe GR. Lung cancer mortality between 1950 and 1987 after exposure to fractionated moderate dose rate ionizing radiation in the Canadian fluoroscopy cohort study and a comparison with lung cancer mortality in the atomic bomb survivors study. Radiat Res. 1995;142:295–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Davis HG, Boice JD, Hrubec Z, Monson RR. Cancer mortality in a radiation-exposed cohort of Massachusetts tuberculosis patients. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6130–6136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kostyuchenko VA, Krestina LY. Long term irradiation effects in the population evacuated from the East-Urals radioactive trace area. The Science of the Total Environment. 1994;142:119–125. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(94)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Koshurnikova NA, et al. Studies of the Mayak nuclear workers: health effects. Radiat Environ Biophys. 2002;41:29–31. doi: 10.1007/s00411-001-0130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sakamoto K, Myogin M, Hosoi Y, et al. Fundamental and clinical studied on cancer control with total and upper half body irradiation. J Jpn Soc Ther Radiol Oncol. 1997;9:161–175. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen WL, et al. Is chronic radiation an effective prophylaxis against cancer? J Am Physicians and Surgeons. 2004;9:6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gilbert ES, Petersen GR, Buchanan JA. Mortality of workers at the Hanford site: 1945–1981. Health Phys. 1989;56:11–25. doi: 10.1097/00004032-198901000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tokarskaya ZB, Okladlnikova ND, Belyaeva ZD, Drozhko EG. Multifactorial analysis of lung cancer dose-response relationships for workers at the Mayak Nuclear Enterprise. Health Phys. 1997;73:899–905. doi: 10.1097/00004032-199712000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Voelz GL, Wilkinson CS, Acquavelle JF. An update of epidemiologic studies of plutonium workers. Supplement 1 to Health Phys. 1983;44:493–503. doi: 10.1097/00004032-198306001-00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Herzog P, Rieger CT. Risk of cancer from diagnostic x-rays [Commentary] Lancet. 2004;363:340–341. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15470-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tubiana M, Aurengo A, Masse R, Valleron AJ. Risk of cancer from diagnostic x-rays [Letter to Editor] Lancet. 2004;363:1908. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nagataki S. Risk of cancer from diagnostic x-rays [Letter to Editor] Lancet. 2004;363:1909. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16372-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Debnath D. Risk of cancer from diagnostic x-rays [Letter to Editor] Lancet. 2004;363:1909. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16388-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Berrington de Gonzalez A, Darby S. Risk of cancer from diagnostic x-rays [Author's Reply] Lancet. 2004;363(1910) doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15433-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Simmons JA. Risk of cancer from diagnostic x-rays [Letter to Editor] Lancet. 2004;363:1908–1909. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16371-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Duport P. A data base of cancer inductionby low-dose radiation in mammals: overviews and initial observations. Int J Low Radiation. 2003;1:120–131. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Calabrese EJ, Baldwin LA. Toxicology rethinks its central belief. Nature. 2003;421:691–692. doi: 10.1038/421691a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ammendolia C, Bombardier C, Hogg-Johnson S, et al. Views on radiagraphy use for patients with acute low back pain among chiropractors in an Ontario community. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2002;25:511–520. doi: 10.1067/mmt.2002.127075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mootz RD, Hoffman LE, Hansen DT. Optimizing clinical use of radiography and miimizing radiation exposure in chiropractic practice. Top Clin Chiro. 1997;4(1):34–44. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Haas M, Taylor JAM, Gillette RG. The routine use of radiographic spinal displacement analysis: a dissent. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1999;22(4):254–259. doi: 10.1016/s0161-4754(99)70053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hansen D, Belmont L, Fairbanks V, et al. Views on radiography use for patients with acute low back pain among chiropractors in an Ontario community [Letter to Editor] J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004;27(3):218–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2003.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Troyanovich SJ. Reliability of Spinal Displacement Analysis on Plane X-rays: A Review of Commonly Accepted Facts and Fallacies with Implications for Chiropractic Education and Technique. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1998;21(4):252–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Troyanovich SJ, Harmon S. A normal spinal position: It's time to accept the evidence. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000;23(9):623–644. doi: 10.1067/mmt.2000.110941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Harrison DD, Cailliet R, Janik TJ, et al. Elliptical modeling of the sagittal lumbar lordosis and segmental rotation angles as a method to discriminate between normal and low back pain subjects. J Spinal Disord. 1998;11(5):430–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McAviney J, Schulz D, Bock R, Harrison DE, Holland B. Determining the relationship between cervical lordosis and neck complaints. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28(3):187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Harrison DD, Harrison DE, Janik TJ, et al. Modeling of the sagittal cervical spine as a method to discriminate hypolordosis: results of elliptical and circular modeling in 72 asymptomatic subjects, 52 acute neck pain subjects, and 70 chronic neck pain subjects. Spine. 2004;29(22):2485–2492. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000144449.90741.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Harrison DE, Jones EW, Janik TJ, Harrison DD. Evaluation of axial and flexural stresses in the vertebral body cortex and trabecular bone in lordosis and two sagittal cervical translation configurations with an elliptical shell model. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2002;26(6):391–401. doi: 10.1067/mmt.2002.126128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Janik TJ, et al. Comparison of axial flexural stresses in lordosis and three buckled configurations of the cervical spine. Clinical Biomech. 2001;16:276–284. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(01)00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Harrison DE, Cailliet R, Harrison DD, Janik TJ, Holland B. A new 3-point bending traction method for restoring cervical lordosis and cervical manipulation: A nonrandomized clinical controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2002;83(4):447–453. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.30916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Harrison DE, Cailliet R, Harrison DD, Janik TJ, Holland B. Changes in sagittal lumbar configurations with a new method of extension traction: Nonrandomized clinical controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2002;83(11):1585–1591. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.35485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Harrison DE, Cailliet R, Betz J, et al. Conservative methods for reducing lateral translation postures of the head: A non-randomized clinical control trial. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2004;41(4):631–639. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2003.05.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Betz J, et al. Increasing the cervical lordosis with seated combined extension-compression and transverse load cervical traction with cervical manipulation: Nonrandomized clinical control trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003;26(3):139–151. doi: 10.1016/S0161-4754(02)54106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Harrison DE, Cailliet R, Betz J, et al. A non-randomized clinical control trial of Harrison mirror image methods for correcting trunk list (lateral translations of the thoracic cage) in patients with chronic low back pain. Euro Spine J. 2005;14(2):155–162. doi: 10.1007/s00586-004-0796-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Practicing Chiropractors’ Committee on Radiological Protocols (PCCRP). Practicing Chiropractors’ Guidelines for the Utilization of Plain Film X-Ray Imaging for the Biomechanical Assessment, Characterization, and Quantification of Spinal Subluxation in Chiropractic Clinical Practice. Arlington, VA: International Chiropractic Association, July 2006.

- 98.Khorshid KA, Sweat RW, Zemba DA, Zemba BN. Clinical efficacy of upper cervical versus full spine chiropractic care on children with autism: a randomized clinical trial. J Vertebral Subluxation Res. 2006 March 9;:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Plaugher G. The Role of Plain Film Radiography in Chiropractic Clinical Practice. Chiropractic J of Australia. 1992;22(4):153–61. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sweat RW, Sweat MH. Guidelines for pre-and post-radiographs for care documentation. Todays Chiropr. 1995;24:2. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jean-Yves Maigne. Is there a need for routine X-rays prior to manipulative therapy? Recommendations of the SOFMMOO French Society of Orthopaedic and Osteopathic Manual Medicine. www.sofmmoo.com/english_section/recommendations/radio.htm Accessed May 29th, 2006.

- 102.Bull PW. Relative and absolute contraindications to spinal manipulative therapy found on spinal x-rays. Proceedings of the World Federation of Chiropractic 7th Biennial Congress; Orlando, FL, May 2003, page 376.

- 103.Pryor M, McCoy M. Radiographic findings that may alter treatment identified on radiographs of patients receiving chiropractic care in a teaching clinic. J Chiropractic Education. 2006;20(1):93–94. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Beck RW, Holt KR, Fox MA, Hurtgen-Grace KL. Radiographic Anomalies That May Alter Chiropractic Intervention Strategies Found in a New Zealand Population. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004;27(9):554–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kendrick D, Fielding K, Bentley E, Kerslake R, Miller P, Pringle M. Radiography of the lumbar spine in primary care patients with low back pain: randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;322(7283):400–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7283.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kendrick D, Fielding K, Bentley E, Miller P, Kerslake R, Pringle M. The role of radiography in primary care patients with low back pain of at least 6 weeks duration: a randomized (unblinded) controlled trial. Health Technol Assess. 2001;5(30):1–69. doi: 10.3310/hta5300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Latov N. Evidence-Based Guidelines: Not Recommended. J Amer Physicians Surgeons. 2005;10(1):18–19. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sherman R. Chiropractic x-ray rationale. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 1986;30(1):33–35. [Google Scholar]