Recognizing the need for clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) in chiropractic, The Canadian Chiropractic Association (The CCA) and the Canadian Federation of Chiropractic Regulatory Boards (CFCRB) launched The CCA/CFCRB-CPG to develop and deploy CPGs for chiropractic.

The profession of chiropractic accounts for physical and other influences on a person’s health. It can be integrated alongside the interventions of other disciplines into a care plan. Appendix 1 lists the practice principles that should be considered in interpreting a CPG for chiropractic, and the principles that should be respected in developing and deploying the CPG.

Sections 1 to 5 of this report describe The CCA/CFCRB-CPG and its origins. Section 6 maps the plan for the development, dissemination, implementation, evaluation, and revision of each CPG. Section 7 elaborates on the details of this plan, and illustrates the research evidence supporting the plan.

1. Introduction

The CCA/CFCRB-CPG will be developing and deploying CPGs to assist chiropractors in daily practice. These CPGs will help to collate the extensive research and clinical expertise that exists within the profession. In addition, these CPGs can inform consumers about the harm-benefit balance of interventions and, through the education of practitioners, contribute to quality-assurance.

CPGs gather, appraise and combine evidence, attempting to address all the issues and values that might sway a clinical decision. In so doing, CPGs refine clinical questions, balance trade-offs and apply qualitative reasoning. CPGs provide explicit practice recommendations, or cost or decision models that reflect value judgements about the importance of various health and economic outcomes.

Although CPGs link the best available evidence to good clinical practice, they are only one component of a well-informed approach to providing good care.1–3 Other components include: information about patients’ preferences and values, practitioners’ personal and professional values and experience, and available resources.4,5

The CCA/CFCRB Guidelines Development Committee.

Back Row, Left to Right: Dr. Normand Danis, Dr. Roland Bryans, Dr. Grayden Bridge (President of The CCA), Dr. Rick Ruegg, Dr. Brock Potter, Dr. Henri Marcoux. Front Row, Left to Right: Prof. Janice Gross-Stein, Dr. Andrea Furlan, Dr. Liz Anderson-Peacock, Dr. Wanda Lee MacPhee (CFCRB President), Dr. Eleanor White.

Each CPG The CCA/CFCRB-CPG is developing and deploying will reflect a well-substantiated consensus about treatment options based on current available evidence. However, CPGs are not standards of care that dictate practice,6–8 but rather guides and tools for chiropractors and their patients. The distinction between a CPG and a standard of care is particularly important to uphold within the Canadian chiropractic profession – primarily because the distinction is poorly defined at the front line of practice. Biggs et al.6 showed that there was “no agreement about the definition of standards of care” in the profession.

2. The foundation of The CCA/CFCRB-CPG

2.1. The need for clinical practice guidelines in chiropractic

By the early 1990s there was sufficient research evidence to develop an evidence-based guideline for the chiropractic management of low-back pain in adults. Clinical recommendations for other age groups, for pain of specific durations, or for pain in spinal areas other than the lower back consisted of educated extrapolations from this research. The 1993 Guidelines for Chiropractic Practice in Canada9 (the ‘Glenerin’ guidelines) reflected this. These were the most comprehensive set of CPGs specifically for Canadian chiropractors – they covered 20 areas of chiropractic practice, and incorporated the near-simultaneous guideline work at the Mercy Center10 in the United States.

Since the early 1990s, the evidence base about chiropractic has grown steadily. In parallel, the accepted methods of creating and deploying CPGs have become more systematic, transparent and rigorous.11 However, a systematically developed CPG has not yet been brought to the Canadian chiropractic profession.

By the late 1990s, the Canadian profession broadly agreed that the Glenerin guidelines did not optimally support chiropractors’ evolving use of CPGs.12,13 Studies of shifting practice patterns suggested chiropractors increasingly relied on up-to-date CPGs to support their practice,13 and were supportive of CPGs.6 The use of guidelines in practice has been reported to respond to concerns of patients, the practicalities of practice (e.g., resources, payer priorities), and the profession’s desire to evolve.6,8,14

2.2. The CCA and CFCRB as producers of CPGs for chiropractic

Practitioners’ opinions about the producer of a CPG are predictive of practitioners’ use of this advisory information. Practitioners’ trust in the producer (attributed credibility) appears to be the most important factor in supporting a successful CPG initiative.15 Indeed, Biggs et al.6 suggested that if chiropractors believe in the group producing their CPGs, they may respect the CPG recommendations even when they differ from the chiropractors’ philosophical and practice beliefs.

This attributed credibility is based on opinions about the producer’s trustworthiness primarily, and expertise secondarily. Other opinions that are important in supporting a successful CPG initiative relate to the producer’s competence as a producer, sensitivity to practitioner concerns, objectiveness, and commitment towards the initiative.16

Biggs et al.6 inferred from their survey that The CCA was the most appropriate producer of chiropractic CPGs. Provincial licensing organizations were also favored, but to a lessor degree. This agrees with findings in other clinical disciplines that practitioners have a strong trust in their professional associations producing CPGs.17

3. Establishing a structure for The CCA/CFCRB-CPG

Deliberations at The CCA through 1999 led to the consensus that a new set of CPGs for the profession should be developed. In 2001, The CCA invited the CFCRB to join this endeavor, and The CCA/CFCRB-CPG was initiated in 2002.

A Joint Task Force (JTF) with members from The CCA and the CFCRB was established to oversee the initiative (Table 1). A Guidelines Development Committee (GDC; Table 2) and a self-sustaining secretariat was established to directly manage the work of The CCA/CFCRB-CPG. In addition, 29 organizations (stakeholders) were enlisted to advise the committee (Table 3).

Table 1.

Appointed members of the JTF

| Grayden Bridge, DC, Chair – The CCA |

| Jim Duncan, BFA, ex-officio – The CCA |

| Wanda Lee MacPhee, BSc, DC – CFCRB |

| Bruce Squires, BA, MBA, ex-officio – OCA |

| Greg Stewart, BSc, DC – The CCA |

| Keith Thomson, BSc, DC, ND, CCRD – CFCRB |

| Dean Wright, DC ex-officio – OCA |

Table 2.

Appointed members of the GDC

| Liz Anderson-Peacock, BSc, DC, DICCP (USA) –Ontario |

| Roland Bryans, BA, DC, Co-Chair – Newfoundland and Labrador |

| Normand Danis, DC, Co-Chair – Quebec |

| Andrea Furlan, MD (Brazil), Phys Med Rehab (Brazil), PhD (cand) – Inter-professional Representative |

| Henri Marcoux, DC – Manitoba |

| Brock Potter, BSc, DC – British Columbia |

| Rick Ruegg, BSc, PhD, DC – CMCC |

| Jean-Sébastien Blouin, DC PhD – UQTR |

| Janice Gross Stein, BA, MA, PhD – Public Representative |

| Eleanor White, DC – Ontario |

Table 3.

Stakeholder organizations

| Association des Chiropraticiens du Québec |

| Board of the Nova Scotia College of Chiropractors |

| British Columbia Chiropractic Association |

| British Columbia College of Chiropractors |

| Canadian Chiropractic Historical Association |

| Canadian Chiropractic Protective Association |

| Canadian Chiropractic Research Foundation |

| Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College |

| Chiropractic Awareness Council |

| Chiropractic College of Radiologists |

| College of Chiropractic Orthopedists |

| College of Chiropractic Rehabilitation Sciences |

| College of Chiropractic Sciences |

| College of Chiropractic Sports Sciences |

| College of Chiropractors of Alberta |

| College of Chiropractors of Ontario |

| Council of the Nova Scotia College of Chiropractors |

| Council of the Prince Edward Island Chiropractic Association |

| Council on Chiropractic Education of Canada |

| Manitoba Chiropractors’ Association |

| New Brunswick Chiropractors’ Association |

| Newfoundland & Labrador Chiropractic Association |

| Newfoundland & Labrador Chiropractic Board |

| Ordre des Chiropraticiens du Québec |

| Ontario Chiropractic Association |

| Prince Edward Island Chiropractic Association |

| The Chiropractors’ Association of Saskatchewan |

| Yukon Territory, Chiropractic Registrar, Department of Justice |

| Université du Québec à Trois Rivières |

An editorial and specialist team from Eglington Health Communications Inc was engaged. The team comprised two individuals from outside of the profession: Thor Eglington RN MSc (President, Editor-in-Chief) and Bruce P Squires MD PhD (Senior Editorial Advisor). In addition to its editorial role, the team used its extensive background in the processes of developing and deploying CPGs for general, women’s and aboriginal health to advise The CCA/CFCRB-CPG.

3.1. Practitioner collaboration

The CCA/CFCRB-CPG examined the need for CPGs with the help of a commissioned paper.7 The CCA/CFCRB-CPG responded to the issues raised in this paper and a review of the Glenerin guidelines by confronting one of the perceived inadequacies of that process – lack of input from front-line practitioners. This is a weakness in CPG development across clinical professions,12,18 including some recent efforts in chiropractic.7,12,13,19

Separately, a lack of communication between the Glenerin process and front-line practitioners was identified as a critical problem. Research has suggested this undermines practitioners’ opinions about CPG processes, and reduces their confidence that the processes share their philosophical and practice perspectives.15

The participation of 29 stakeholder organizations in The CCA/CFCRB-CPG was designed to enable widespread participation of front-line chiropractors through their membership in these organizations, and several of these organizations will also enable communication with the lay-public. The usefulness of this approach is well founded in the CPG and information-dissemination literature,5,15 and has been validated as the best approach in recent work about chiropractic.6,12

4. Establishing the clinical area in need of clinical practice guidelines

The choice of the area in which to develop new CPGs (Table 4) was guided by the advice of stakeholder organizations, and an understanding that CPGs are most useful as information tools in a few well-delineated circumstances5,11,20 (Table 5). This approach is well supported in the literature.7,21,22

Table 4.

Areas of focus for The CCA/CFCRB-CPG

| In meetings that took place in September and November, 2002, The CCA/CFCRB-CPG and representatives of chiropractic organizations ratified a selection of clinical topics to be dealt with by this initiative. These topics all fell under the rubric of cervical spine. |

| – adult neck pain: acute |

| – adult neck pain: chronic |

| – adult neck pain with arm pain |

| – adult cervical discogenic pain |

| – adult thoracic outlet syndromes |

| – adult headache: without neck pain |

| – adult headache: with neck pain |

| – adult whiplash injury |

| – adult cervicogenic vertigo |

| – pediatric neck pain without headache |

| – pediatric headache without neck pain |

| – pediatric headache with neck pain |

| – geriatric neck pain without headache |

| – geriatric headache without neck pain |

| – geriatric headache with neck pain |

Table 5.

Circumstances appropriate for CPG development

| A CPG is a useful information tool where there is a literature or specialist evidence-base of usable caliber that is applicable to solving a clinical problem, and: |

| – where a significant variation in practice is noted, and a health outcome detriment is suspected; |

| – or – |

| – where new information that has an impact on existing practice patterns has become available; |

| – or – |

| – where the prevalence or incidence of a condition/intervention is believed to be abnormal; |

| – or – |

| – where the burden associated with a condition/intervention is believed to be abnormal; |

| – or – |

| – where the cost-differential between therapeutic options is significant; |

| – or – |

| – where the existing knowledge-base developed to support a practice is believed to be insufficiently effective. |

Chiropractic management of the cervical spine was ranked as the most important focus. Subsequent literature investigation showed that this encompassed a range of topics that was too great to be incorporated into one effective CPG. A list of specific clinical issues to be considered was established in July 2003:

– adult neck pain – acute not due to whiplash, and chronic not due to whiplash;

– adult whiplash;

– adult neck pain with arm pain;

– adult neck function and structure detriments;

– adult headache.

5. Establishing CPG processes best suited to chiropractic

The principles governing successful development (creation of the text content), dissemination, implementation, evaluation, and revision of a CPG have been extensively researched. At least 200 recent articles delve into the practical, economic, sociologic, psychologic, and professional underpinnings of getting CPGs ‘out there and used.’ This body of literature (see Section 7) describes a framework of ‘effectors of practice behavior’ that a CPG initiative should address, and a roster of barriers the initiative should overcome.23,24

Two (2) significant components were incorporated into The CCA/CFCRB-CPG to accommodate these effectors and barriers, the points made in Sections 1 to 4, and respect the literature:

– an independent review panel;

– an integrated development, dissemination, implementation, evaluation, and revision plan.

5.1. Independent review panel

The independence of content developers is one of the mainstays of high quality CPGs.13 Various CPG ranking scales25–27 such as the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation Instrument28 (AGREE) include this variable in their scoring mechanisms. CPG databases such as the Canadian Medical Association’s Infobase (CMAi)29 and the US National Guidelines Clearinghouse (NGC)30 include a description of editorial independence as part of their critical information lists.

A different, independent panel of advisors will advise the GDC about the recommendations of each CPG. Panelists will include clinical professors, clinical researchers, and well-regarded practicing chiropractors. These advisors will bring to the CPG aspects of the state-of-the-art of practice that were not well represented in the literature.

The panel will formulate clinical recommendations based on well-informed opinion when necessary. The panel will also ensure that the CPG is clinically relevant, and will represent the various relevant practice viewpoints.

The panel will also advise the GDC about how the recommendations of each CPG are effectively implemented in the clinical setting. Their advice will be included in the CPG separate from the recommendations, such as in ‘question-and-answer’ lists.

5.2. Integrating development, dissemination, implementation, evaluation, and revision

5.2.1. Development plan

An 11-step development plan was refined through the summer of 2003. This plan upholds the critical precepts of developing the evidence-based content of the CPG. These precepts are described in Section 7.1.

5.2.2. DIER plan

Building on this past decade’s literature and the accepted importance of dissemination, implementation, evaluation, and revision (DIER) activities, recent national CPG initiatives have focused a significant amount of effort on DIER activities. These activities are frequently the most laborious and costly. A good example is the extensive CPG dissemination mechanism devised by the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care.4,31,32

A first draft of a plan for the DIER activities was presented by the editorial team to the GDC and its overseer, the JTF, mid-September, 2003. This draft included 27 activities that would be effective in supporting the dissemination, implementation, evaluation, or revision of the CPG. These 27 were individually ranked from ‘must-do’ through to a low score of 2/10, based on:

– likelihood of success,

– impact if successful,

– potential to drive other beneficial outcomes.

In addition to individual scoring, the most effective and efficient combinations of activities were considered. Effectiveness and efficiency opinions took into account each activity’s:

– effect at each stage of the life-cycle of the CPG (development through to revision);

– effect on the effectors of practitioners’ behavior;

– avoidance, dissolution or circumvention of barriers to implementation;

– ability to support communication between practitioners and The CCA/CFCRB-CPG.

The DIER activities were ranked in order of priority and approved by the GDC for further consideration as part of the DIER plan for The CCA/CFCRB-CPG. The plan was then presented at a meeting of the stakeholder organizations to elicit feedback. Comments were gathered and incorporated into the DIER plan. Finally, comments from front-line chiropractors and others in critical health-service roles from across Canada were gathered through an Internet-based consultation.

These consultations resulted in refinement of the DIER activities. The refined activities were then interwoven with the work of developing the text content of each CPG.

5.2.3. Integrating development and DIER plans

Throughout their formulation, the DIER activities were considered in light of their fit with ongoing development activities. Several reports support this parallel processing in developing and deploying CPGs.5,16,21,33 This literature reflects the common sense in ensuring that the text content of the CPG is tailored to its context of use – before, during and after it is developed.

6. The development, dissemination, implementation, evaluation, revision (DevDIER) plan

A development, dissemination, implementation, evaluation, and revision (DevDIER) plan with 10 activities involved in developing the text content of each CPG, and 14 DIER activities was developed. Together, these 24 activities target chiropractors likely to agree, and those likely to disagree, with the CPG process.

These activities support each other, leading to the increased efficiency and effectiveness of each. Table 6 lists all 24 activities, showing the effect of each activity on each of the 5 stages of development, dissemination, implementation, evaluation, and revision. Most of these activities affect at least 2 stages, further increasing efficiency and effectiveness.

Table 6.

An integrated 24-step DevDIER

| not necessarily in order of commencement or completion

“DRAFT” below refers to versions of the CPG development activities no shading, DIER activities shaded |

development | dissemination | implementation | evaluation | revision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | appoint editorial advisors (editor-in-chief, senior editorial consultant) | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| 2 | create CPG template (tightly linked to AGREE instrument) that guides content development | yes | yes | |||

| 3 | create terms of reference & appoint independent review panels | yes | yes | |||

| 4 | create dissemination, implementation, evaluation, revision (DIER) plan | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| 5 | release evidence-assessor request for proposal with template & levels of evidence rating table

– evaluate proposals using a standardized scoring grid |

yes | ||||

| 6 | DRAFT-A to -B – evidence-assessor finalizes first draft of CPG | yes | ||||

| 7 | DRAFT-B to -C – GDC (formal authors) reviews DRAFT-B | yes | ||||

| 8 | DIER approved & create and publish DevDIER (this report) | yes | yes | |||

| 9 | DRAFT-C to -D – review panel reviews DRAFT-C

– validate clinical accuracy and advise GDC about Grade-D recommendations – validate clinical applicability of all recommendations |

yes | yes | |||

| 10 | practitioners and interested parties anonymously critique DRAFT-D about its clinical utility

– using a structured Internet-based consultation based on the AGREE; i.e., an eQuestionnaire and a structured text feedback mechanism |

yes | yes | yes | ||

| 11 | DRAFT-D to -E – incorporate feedback from practitioners and interested parties | yes | ||||

| 12 | inform stakeholder organizations about the impact of feedback from #10 on CPG | yes | ||||

| 13 | initiate AGREE collaboration – to evaluate final CPG (DRAFT-G) using the AGREE instrument, with a view to publishing results | yes | yes | yes | yes | |

| 14 | DRAFT-E to -F – GDC (formal authors) reviews DRAFT-E | yes | ||||

| 15 | DRAFT-F to -G – JTF and The CCA & CFCRB Boards formally accept DRAFT-F | yes | ||||

| 16 | submit final CPG (DRAFT-G) to the JCCA for peer revue and acceptance | yes | ||||

| 17 | undertake self-report CPG tri-evaluation – front-line evaluation of document caliber, self-reported use rates, self-reported clinical outcomes | yes | yes | yes | ||

| 18 | facilitate a formal outcomes research evaluation study | yes | yes | yes | ||

| 19 | create publications for the lay-public & patients using the CPG | yes | yes | |||

| 20 | facilitate the incorporation of the CPG into education, continuing education, licencing | yes | yes | |||

| 21 | create CPG-specific newsletter articles – best-of implementor bios, best-of implementation write-ups, case-studies for problem-solving, feedback channel for practitioners, patient feedback, updates on CPG process/progress | yes | yes | yes | ||

| 22 | create and disseminate case-study template to drive newsletter article submissions | yes | yes | yes | ||

| 23 | create and disseminate briefing notes about the impact of each CPG on various policy issues | yes | yes | |||

| 24 | manage the update or revision of the publicized CPG – evaluate need for update/revision every 6 months, formal revision every 18 months expected | yes | yes | |||

7. The evidence-based approach of the DevDIER plan

The DevDIER plan is an evidence-based approach to the activities of development, dissemination, implementation, evaluation, and revision. Section 7 reflects a synthesis from references #1, 3–8, 11, 12, 20–28, 31, 33–52. Some points are specifically referenced where appropriate.

7.1. Evidence-based approach to development

The content of the CPG will be reinforced by avoiding excessive reliance on clinical opinion, unsystematic literature analyses, or ambiguous understandings of front-line information needs.5,19,21,27,38,39 In addition, a content-development approach steeped in the ‘information dissemination’ literature about the usefulness of CPGs will be used. This approach can be described along 5 dimensions:

– content consistency (consistent caliber and style across all CPGs),

– content purity (valid and reliable representation of the content source),

– content alignment with practice,

– content support (ancillary support for content implementation),

– problem-solving (presenting complaint) approach of content.

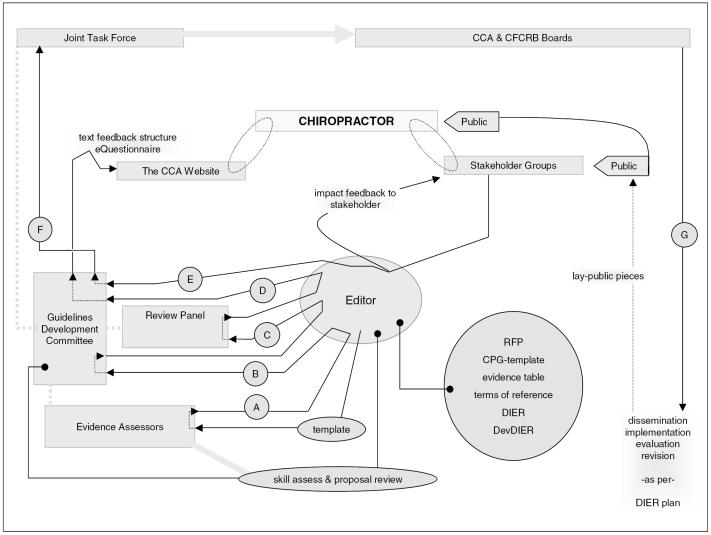

All 5 dimensions will be addressed by the CPG development activities (DevDIER activities 1 to 3, 5 to 7, 9, 11, 14, 15). These dimensions will also be addressed by several of the activities of dissemination (Section 7.2), implementation (Section 7.3), evaluation (Section 7.4), and revision (Section 7.5). Figure 1 maps the work-flow of the development operations of The CCA/CFCRB-CPG.

Figure 1.

The work-flow of the development operations of The CCA/CFCRB-CPG (letters indicate draft version)

7.1.1. Content consistency across the CPG series

CPG template.

A template will ensure consistency across the development of multiple CPGs using different authors, evidence assessors or advisory groups. A template is an effective feature of national CPG initiatives, such as the New Zealand Guidelines Group,53 and is increasingly seen as an imperative first step in CPG development.54

The template will incorporate standards from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors’ Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals,55 will reinforce the use of simple language, and will incorporate a problem-solving approach. This will promote the applicability of the CPG to the clinical setting.

In addition, the template will be tightly linked to the AGREE, which will be used to evaluate the CPG document. A template intimately linked to its evaluation tool ensures all essential areas are covered, and respects the literature’s support for evaluation mechanisms being considered early in the development process.20

Levels of evidence rating table.

The Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEBM) levels of evidence rating table56 will be used as a comprehensive evidence-rating tool. This table helps to mate each of 5 possible levels of evidence a study supports, with one of 4 grades of recommendations that arise from that evidence. A methodologically perfect systematic review (SR), with clarity in the clinical and statistical significance of its results, has the greatest credibility (Level-1 evidence). Level-1evidence will likely support a Grade-A (almost certain) recommendation. An SR with methodological weakness will likely support only a lessor grade of recommendation.

In chiropractic, high-quality studies are lacking in some areas where clinical decisions must be made. Recommendations in these areas will rely on the well–informed opinions of review panelists, based on their clinical experience and knowledge of lower-quality studies. This evidence can be rated as low as Level-5, and these recommendations as low as Grade-D. However, opinion that is based solely on a panelist’s personal intuition will not be accepted into The CCA/CFCRB-CPG guidelines – all recommendations will be linked to the literature.

Essentially, the grade of recommendation will reflect the CPG authors’ confidence in the recommendation.5 For example, the same grade of recommendation may arise from Level-2 evidence as would arise from Level-1 when consistent, significant results are obtained from several wholly independent Level-2 studies.

This method of grading has been adapted for use in many well-received CPGs, including those dealing with breast cancer,57 diabetes mellitus,58,59 and the Australian 2001 adaptation60 of the Quebec Task Force’s whiplash monograph.61

Evidence assessor RFPs.

Standardized requests for proposals (RFP) to assess the evidence, and a standardized proposal-evaluation grid will ensure The CCA/CFCRB-CPG administrative groups systematically enforce consistency across different evidence assessor teams. RFPs will provide assessor teams with the CPG template, the OCEBM levels of evidence rating table, and address issues of intellectual property.

Review panel terms of reference.

Terms of reference for the panel will delineate panelists’ role in the development process. Different panels will likely address each CPG, and these terms will ensure panelists’ approach will be consistent. This method is common in large CPG initiatives.62–65

7.1.2. Content purity

The CCA/CFCRB-CPG development strategy will be founded on its accountability for preserving the accuracy, authenticity and integrity of the information contained within each CPG, irrespective of the information’s original source. This is in keeping with the best practice of information management by organizations representing a constituency.40

In chiropractic, maintaining the accuracy, authenticity and integrity of the content of each CPG is especially important. The profession represents a broad spectrum of practice types,6 and any recommendation put forth must be able to withstand the scrutiny of all chiropractors, as well as external bodies.

In addition to the development activities, activities #13 (AGREE evaluation-publication), #18 (outcomes research) and #24 (revision) will directly reinforce the valid and reliable representation of the source content in each CPG.

7.1.3. Content alignment with practice

The two aspects of content that promote the use of the CPG most are the conformity of its content to practitioners’ expectations and its alignment with their day-to-day experiences.11,41–43 In contrast, neither the purity of the content (Section 7.1.2.) nor the caliber of its evidence accurately predict whether the CPG will be used.

Where recommendations are expected to be misaligned with some practitioners’ day-to-day experiences, their reduced use can be countered by accommodating these practitioners’ existing knowledge. This can be done with a section that translates graded recommendations into practice patterns (e.g., implementation ‘question & answer’ lists). In addition, practitioners’ evaluation of the CPG prior to publication can direct which areas of content need to be reinforced in this manner.

The development activities will reinforce content alignment (e.g., review panel). Activity #10 (eQuestionnaire) will provide an early feedback conduit. Activities #12 (impact feedback) and #8 (this report) will acquaint the profession with the concepts of the CPG. Activity #19 (lay pieces) will enable patients to use the concepts in the CPG to present their problems and requests, strengthening the similarity between day-to-day practice and the CPG. Activity #20 (curricula, continuing chiropractic education [CCE], licencing) will familiarize future practitioners with the content and format of future CPGs. Activity #23 (policy briefs) will support the alignment of policy with the recommendations within the CPG.

7.1.4. Content support

Careful response to practitioners’ need for guidance about implementing recommendations will help practitioners incorporate these into their practice. Guidance is in the form of ‘non-core information’ apart from the content that is the focus of each CPG, and may include:5,20

– Information about adapting the original content to practitioners’ resources, needs, concerns, or circumstances. Activity #10 (eQuestionnaire) will gather this information, #21 (newsletter) will provide a vehicle to exchange this information, and #22 (case template) will gather this information on an ongoing basis. Activity #19 (lay pieces) will support patients’ use of CPG-based concepts to inform practitioners of their concerns and context.

– Information about dissemination, implementation, evaluation, and revision (DIER) activities. Activity #8 (this report) will inform the profession about the support activities of each CPG early in the CPG process.

7.1.5. Problem-solving (presenting complaint) approach of content

The use of problem-solving in the CPGs The CCA/CFCRB-CPG CPG is producing is well supported.7 Constructivism is the foremost theoretic base explaining the use of problem-solving44 to support practice decisions.15,42 Its main premises are reflected in the understanding that:

– practitioners’ mental re-constructions of recommendations strongly reinforce incorporating these into practice; 45

– practitioners construct practice decisions out of a mix of personal experiences and beliefs, as well as supplied recommendations.4,11

Problem-solving content in the CPG eases practitioners’ mating of the content to their practice experiences. Practitioners are more likely to re-construct problem-solving recommendations, pondering how the recommendations would cope with one clinical situation or another. For this reason and others based in education theory, problem-solving content is considered one of the hallmarks4,21,28,38 of a better CPG.

The development activities will reinforce a problem-solving approach. Activity #8 (this report) will enable us to separately publish the methods that are not specific to each CPG, thereby maximally distilling the text of each CPG into its problem-solving recommendations. Activity #17 (tri-evaluation) will reinforce practitioner’s efforts to deliberate about the CPG in a problem-solving manner. Activity #18 (outcomes research) will facilitate useful revisions to the clinical problem-solving statements in each CPG. Activity #20 (curricula, CCE, licensing) will rest on the problem-solving approach of each CPG; this respects the format of case seminars, and the problem-solving foundation of adult learning theory.44 Activity #21 (newsletter) will provide a communication network for problem-solving (case-study) reporting of the usefulness of the CPG. Activity #22 (case template) will reinforce a systematic problem-solving premise for using the CPG in practice.

7.2. Evidence-based approach to dissemination and implementation

In its simplest form, disseminating a CPG is the act of moving it through a ‘channel,’ from its source to a repository (e.g., a CPG database), and thereby to a practitioner. However, the mere provision of a CPG is unlikely to change practice behaviors.4,5,7,11,15,21–24,31,34–36,41–43,45,46

As a result, dissemination must be considered in tandem with implementation. Together, they encompass several other concepts; e.g., information diffusion, knowledge transfer or utilization, information-seeking, and learning. Indeed, much of the literature muddies the line between these concepts.

Dissemination-implementation comprises 4 general objectives:21,45–48

– To support practice decisions; e.g., by positively influencing practitioners’ judgement and beliefs, or organizations’ professional cultures, thus providing strong support for behavioral change. Activities #16 (CPG publication), #19 (lay pieces), #20 (curricula, CCE, licensing), #21 (newsletter), #22 (case template), and #24 (revision) will directly target practice decisions.

– To instigate response; e.g., by initiating feedback (practitioner surveys and testimonials) that will direct future CPG development activities. Activities #10 (eQuestionnaire), #17 (tri-evaluation) and #18 (outcomes research) will directly instigate a response.

– To initiate a reaction through a series of linkages. This is based on practitioners, using the CPG, directly or indirectly influencing other practitioners’ judgement or organizational outcomes (e.g., policy development). Activities #12 (impact feedback) and #19 (lay pieces) will target reaction through linkages, and activity #23 (policy briefs) will target policy development.

– To create awareness, which provides poor support for behavioral change on its own. Activity #16 (CPG publication) will target awareness.

7.2.1. Dissemination-implementation and information-seeking styles

People find information using 3 different information-retrieval styles:49

– Active – searching based on an awareness that the information exists, using known search tools. The rigor of the CPG-development activities will facilitate the acceptance of each CPG into well-known databases such as the CMAi and NGC.

– Passive – receiving automated delivery of a one-time or periodic subscription, or an information stream. Activities #8 (this report), #13 (AGREE evaluation/publication), and #16 (CPG publication) will respect this style.

– Serendipitous – finding information by chance. Addressing patient’s concerns that have arisen from CPG-based pieces (e.g., activity #19 [lay pieces]) may provide ‘hidden’ opportunities for practitioners to uncover new CPG information.

All 3 styles are respected if the CPG is incorporated into curricula (activity #20).

7.2.2. Dissemination-implementation and readiness to change

Incentives reinforce practitioners’ readiness to change. They may be internal (e.g., practitioners’ sense of self-worth), or external (e.g., job promotion matched to increased performance). It appears that personally meaningful, internal incentives are the most potent.15 External incentives can reinforce internal incentives, but they are not very potent alone.6,15

The effectiveness and efficiency of incentives decrease as the heterogeneity of the practitioner-group increases. This can be countered by targeting practitioners separately along demographic, sociologic and psychologic dimensions.21,48 Targeting involves using different incentives, dissemination-implementation intermediaries, and distribution channels for each target.5 This segmentation is akin to social marketing.

Activities #10 (eQuestionnaire), #13 (AGREE evaluation-publication), #17 (tri-evaluation), and #18 (outcomes research) will value each practitioner’s idiosyncratic, evaluative challenge to the CPG. These activities may thereby be especially relevant to chiropractors who disagree with the CPG process.

Activity #19 (lay pieces) will support an environment within which chiropractors’ efforts to use the CPG are rewarded by patients’ acknowledgment of good practice. Activity #20 (curricula, CCE, licensing) will intrinsically align CPG-based practices with academic recognition and reward.

7.2.3. Dissemination-implementation and distribution channels

The literature consistently suggests that dissemination-implementation should use multiple distribution channels.4,48 There are 3 core distribution channels – activity #20 (curricula, CCE, licensing) is an example incorporating all 3 channels:

– Push channels50 – practitioners are passive recipients of information; e.g., activities #8 (this report), #16 (CPG publication) and #21 (newsletter).

– Pull channels – practitioners actively filter through cues to target and withdraw information they are motivated to seek. The development activities will uphold the acceptance of the CPG into well-known databases such as the CMAi and the NGC.

– Interactive channels – practitioners direct the development of information that is then presented to them after some processing; e.g., activities #10 (eQuestionnaire), #12 (impact feedback), #17 (tri-evaluation), #18 (outcomes research), input into #21 (newsletter), and #22 (case template).

The literature consistently reports that the most effective channel is personal contact with intermediaries,6,15,16,46 termed influentials, linking agents, or boundary-spanners. Effective intermediaries are able to move between one social or professional culture and another (e.g., clinical educators that move between the research and practice milieus), and are considered to be experts that others seek-out for reliable information. The power of interpersonal contact appears to rest on practitioners using face-to-face discussion, to problem-solve around the use of recommendations misaligned with their practice. The more the recommendations are misaligned with their practice, the greater the effect of interpersonal contact. Activities #19 (lay pieces), #20 (curricula, CCE, licencing) and #23 (policy briefs) will provide materials to intermediaries who will ‘introduce’ the CPG content to the public, student chiropractors and policy developers.

7.3. Evidence-based approach to evaluation

The literature almost universally states that the effective development and deployment of CPGs must include a critical evaluation.4,5,7,11,12,19–22,26,27,31,34–36 If possible, some form of evaluation should be undertaken before publication of the CPG, to tailor its development and planned DIER activities.11,20 Activities #10 (eQuestionnaire) and #12 (impact feedback) will directly respond to this.

A critical evaluation includes asking at least 3 questions:

– Is the CPG a sound document?

– Is the CPG an implementable, applicable, pragmatic clinical tool?

– Does the CPG support beneficial clinical outcomes?

7.3.1. Evaluating the CPG document

A foremost evaluation tool in the CPG literature is the AGREE. This instrument specifically evaluates the content structure of a CPG. It does not attempt to directly verify the claims of the CPG, the internal validity of any development-through-to-revision links proposed in the CPG, or the practicality of the recommendations.

In 2001, the Glenerin & CCP guidelines,12 and in 2003, the ICA, CCP and Mercy guidelines19 were evaluated using a version of the AGREE with confirmed validity and reliability.26 Several of the studied CPGs effectively ‘failed’ at least one aspect of the evaluation.

A high rating using the AGREE will likely reinforce practitioners’, payers’ and legislators’ confidence in the credibility of the CPG, and reinforce its cross-professional acceptance as a ‘usefully formatted’ source of guiding information. Indeed, a high score using the AGREE directly suggests that the CPG ‘covered all the bases’ in its development, dissemination, implementation, evaluation, and revision activities.

Activity #13 (AGREE evaluation-publication) will implement an evaluation using the AGREE. In preparation for Activity #13, the CPG structure and content will be guided by activity #2 (CPG template) – a template that will be tightly linked to the AGREE.

The AGREE evaluation-publication will be paralleled by elements of the activities #10 (eQuestionnaire) and #17 (tri-evaluation). These 2 activities will primarily evaluate the clinical utility of the CPG, but will also contain elements that are tightly linked to the AGREE.

7.3.2. Evaluating the use of the CPG

Success in promoting the clinical use of the CPG will be difficult to measure. Activity #17 (tri-evaluation) will directly, albeit coarsely, assesses practitioners’ inclusion of the CPG into their practice. The rate and extent of inclusion of each CPG into practice reflects a catch-bag of desired CPG qualities; e.g., its ease and practicality of use, its cost-effectiveness, or significant clinical outcomes resulting from its use.

7.3.3. Evaluating the impact of the CPG on clinical outcomes

Above all, well-developed and deployed CPGs primarily aim to improve clinical outcomes.5,11,22,51 A difficulty in the history of chiropractic CPGs has been the development of practical outcome measures19 that provide unambiguous guideposts to:

– researchers wishing to further chiropractic science,

– front-line practitioners wishing to assess patients’ progress,

– payers wishing to justify good practices,

– legislators wishing to uphold the privilege of practice for appropriately educated practitioners.66

Activity #17 (tri-evaluation) will directly, albeit coarsely, assesses the outcomes of using the CPG. Activity #18 (outcomes research) will directly support a formal outcomes evaluation. Activity #22 (case template) will provide practitioners with a systematic method of reporting the impact of the CPG on a case-by-case basis.

7.4. Evidence-based approach to revision

A systematic plan for revising the CPG demonstrates a commitment to keep the CPG up-to-date, to allow for its future evolution, and to ensure practitioners’ future participation in enhancing the CPG. Activity #24 (revision) is this commitment.

Several other activities will directly drive the ongoing revision of The CCA/CFCRB-CPG guidelines, by providing or facilitating timely and systematically gathered information. They are the activities #10 (eQuestionnaire), #12 (impact feedback), #13 (AGREE evaluation-publication), #17 (tri-evaluation), #18 (outcomes research), and #22 (case template).

Appendix 1

1. Chiropractic principles

– Chiropractic is a health care discipline that emphasizes the inherent recuperative power of the body to heal itself without the use of drugs or surgery.

– The practice of chiropractic focuses on the relationship between structure (primarily the spine) and function (as coordinated by the nervous system) and how that relationship affects the preservation and restoration of health. In addition, Doctors of Chiropractic recognize the value and responsibility of working in cooperation with other health care practitioners when in the best interest of the patient.

Purpose: the purpose of chiropractic is to optimize health.

Principle: the body’s innate recuperative power is affected by and integrated through the nervous system.

Practice:

Establishing a Diagnosis – Doctors of Chiropractic, as primary contact health care providers, employ the education, knowledge, diagnostic skill, and clinical judgment necessary to determine appropriate chiropractic care and management. Doctors of Chiropractic have access to diagnostic procedures and / or referral resources as required.

Facilitating Neurological and Bio-mechanical Integrity Through Appropriate Chiropractic Case Management – Doctors of Chiropractic establish a doctor / patient relationship and utilize adjustive and other clinical procedures unique to the chiropractic discipline. Doctors of Chiropractic may also use other conservative patient care procedures, and, when appropriate, collaborate with and / or refer to other health care providers.

Promoting Health – Doctors of Chiropractic advise and educate patients and communities in structural and spinal hygiene and healthful living practices.

2. Guideline principles

The CPGs will be prepared using the following principles:

The primary purpose of CPGs is to assist chiropractors and their patients in arriving at decisions on appropriate chiropractic care for specific clinical circumstances. The CPG is developed for the purpose of improving and optimizing patient care.

The CPG is not a practice standard. Standards are defined by a regulatory body and detail the absolute limits on acceptable clinical practice. CPGs on the other hand, are used on a voluntary basis by the chiropractor to assist him / her in making more informed decisions.

CPGs should not be used to restrict healthcare choices nor to decrease costs of care; they should not be considered a legal standard of care by courts.

Clinical practice guidelines should be sufficiently flexible to allow patients and chiropractors to exercise judgement when choosing available options.

Clinical practice guidelines should enable informed decision making by patients and chiropractors by enhancing professional learning, patient education and patient-chiropractor communication.

Clinical practice guidelines should recognize that the chiropractor’s primary responsibility is to his or her own patient, although it may have to be balanced against the needs of other people and society in general.

Ethical issues should be considered in all phases of the clinical practical guideline process.

Clinical practice guidelines should be developed by chiropractors in collaboration with representatives of those who will be affected by the specific interventions in question.

Effective utilization of CPGs requires careful consideration of mechanisms for implementation.

CPGs should be continuously reviewed and revised as necessary, based on feedback from clinical practice and as advances in knowledge occur.

3. Guideline procedural principles

CPGs will be developed by practitioners and supported by review panels and editorial staff.

Rigorous scientific methods will be used to assemble, organize and synthesize the best available evidence.

All processes will be open, transparent and thoroughly documented.

To ensure that CPGs are useful in clinical situations, feedback will be sought from relevant stakeholders, including practitioners and supporting organizations, at defined points throughout the development cycle.

CPGs will be widely disseminated so that they are available to practitioners, patients and the public.

CPGs will be updated on a regular, scheduled basis to incorporate new evidence.

Plans for the implementation of CPGs, the evaluation of their utilization, and the ongoing monitoring of their appropriateness and usefulness to clinical practice, will be developed concurrently to the CPGs.

Footnotes

Author and contact for questions about the report

The CCA/CFCRB-CPG, 39 River Street, Toronto, Ontario M5A 3P1.

Sources of support

This work was funded by an unrestricted grant provided by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care to the Ontario Chiropractic Association.

8. References

- 1.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Muir Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence-based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t [editorial] BMJ. 1996;312:71–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318:527–30. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7182.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell H, Hotchkiss R, Bradshaw N, Porteous M. Integrated care pathways. BMJ. 1998;316:133–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7125.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Effective dissemination and implementation of Canadian task force guidelines on preventive health care: literature review and model development – final report. Ottawa (ON): Health Systems Division, Strategies and Systems for Health Directorate, Health Promotion and Programs Branch, Health Canada; 1999 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hppb/healthcare/pdf/edctfg.pdf

- 5.New Zealand Guidelines Group. Guidelines development handbook. New Zealand: the Effective Practice Institute, University of Auckland; 2003 Oct 23 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.nzgg.org.nz/development.cfm

- 6.Biggs L, Hay D, Mierau D. Standards of care: what do they mean to chiropractors, and which organizations should develop them. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 1999;43(4):249–57. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papadopoulos C. The development of Canadian clinical practice guidelines: a literature review and synthesis of findings. Discussion paper prepared for The CCA/CFCRB Task Force on Chiropractic Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2003;47(1):39–57. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gatterman MI, Dobson TP, LeFevbre R. Chiropractic quality assurance: standards and guidelines. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2001;45(1):11–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henderson D, Chapman-Smith D, Mior S, Vernon H. Clinical Guidelines for Chiropractic Practice in Canada. Toronto (ON): Canadian Chiropractic Association; 1993 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.ccachiro.org/client/CCA/CCAWeb.nsf/web/ClinicalGuidelinesMain?OpenDocument

- 10.Chapman-Smith C, Petersen DM, Haldeman S. Guidelines for chiropractic quality assurance and practice parameters: proceedings of the Mercy Center Consensus Conference. USA: Jones & Bartlett; 1993 (ISBN 083420388X).

- 11.McKinlay E, McLeod D, Dowell T, Howden-Chapman P (Wellington School of Medicine, University of Otago). Clinical practice guidelines: a selective literature review. New Zealand: New Zealand Guidelines Group; 2001 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.nzgg.org.nz/development.cfm

- 12.Brouwers M, Charette M. Evaluation of clinical practice guidelines in chiropractic care: a comparison of North American guideline reports. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2001;45(3):141–53. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Côté P, Hayden J. Clinical practice guidelines: the dangerous pitfalls of avoiding methodological rigor [editorial] J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2001;45(3):154–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freedman AM. Chiropractic audits. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2001;44(2):113–24. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR). A Review of the Literature on Dissemination and Knowledge Utilization. Austin (TX); 1987 [cited 2003 Mar 5]. Available from: http://www.ncddr.org/du/products/litreview.pdf

- 16.National Center for the Dissemination of Disability Research (NCDDR). Guides to improving practice, number two – improving the usefulness of disability research: a toolbox of dissemination strategies. Austin (TX); 1996 [cited 2003 Mar 5]. Available from: http://www.ncddr.org/du/products/guide2.html

- 17.Cook D, Giacomini M. The trials and tribulations of clinical practice guidelines [editorial] JAMA. 1999;281(20):1950–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.20.1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaneyfelt TM, Mayo-Smith MF, Rothwangel J. Are guidelines following guidelines? The methodological quality of clinical practice guidelines in the peer-reviewed medical literature. JAMA. 1999;281(20):1900–05. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.20.1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cates JR, Young DN, Guerriero DJ, Jahn WT, Armine JP, Korbett AB, Bowerman DS, Porter RC, Sandman T, King RA. An independent assessment of chiropractic practice guidelines. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003;26:282–86. doi: 10.1016/S0161-4754(03)00010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham ID, Harrison MB, Brouwers M, Davies BL, Dunn S. Facilitating the use of evidence in practice: evaluating and adapting clinical practice guidelines for local use by health care organizations. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2002;31:599–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2002.tb00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). A guide to the development, implementation and evaluation of clinical practice guidelines. Canberra (Australia); 1999 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/nhmrc/publications/synopses/cp30syn.htm

- 22.Thomson R, Lavender M, Madhok R. Fortnightly review: how to ensure that guidelines are effective. BMJ. 1995;311:237–42. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6999.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eglington T, Squires BP, Jolly E (with Eglington Health Communications Inc). Barriers to.. Implementing clinical practice guidelines. Toronto (ON): Ontario Women’s Health Council. Unpublished internal report; 2000 Mar. Unpublished.

- 24.Eglington T, Squires BP, Jolly E (with Eglington Health Communications Inc). Recommendations for.. action to be taken by the OWHC to reinforce the implementation of clinical practice guidelines in Ontario. Toronto (ON): Ontario Women’s Health Council. Unpublished internal report; 2000 Mar. Unpublished.

- 25.Eglington T, Squires BP, Carter AO (with Eglington Health Communications Inc). Environmental scan and situation analysis of the development of clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of breast cancer in Canada. Ottawa (ON): Health Canada; 1999 Mar. Unpublished.

- 26.Graham I, Calder LA, Hébert PC, Carter AO, Tetroe JM. A comparison of clinical practice guideline appraisal instruments. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2000;16(4):1024–38. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300103095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Clinical guidelines – criteria for appraisal for national use. Dundee (Scotland): Centre for Medical Education, University of Dundee; 1995.

- 28.The AGREE Collaboration. Appraisal of guidelines for research & evaluation (AGREE) instrument. London (England): George’s Hospital Medical School; 2001 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.agreecollaboration.org

- 29.Canadian Medical Association Infobase (CMAi) [database on the Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Medical Association. c1995–2003 [cited 2003 Dec 1]. Available from: http://mdm.ca/cpgsnew/cpgs/index.asp

- 30.National Guidelines Clearinghouse (NGC) [database on the Internet]. Plymouth Meeting (PA): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, in partnership with the American Medical Association and the American Association of Health Plans. c1998–2003 [cited 2003 Dec 1]. Available from: http://www.guideline.gov/

- 31.Feightner JW, Marshall JN, Quintana Y, Wathen CN. Electronic dissemination of Canadian clinical practice guidelines to health care professionals and the public. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, Health Canada; 1999 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hppb/healthcare/pdf/edccpg.pdf

- 32.Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, Health Canada. CTFPHC history/methodology. Ottawa (ON); 2001 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.ctfphc.org/ctfphc&methods.htm

- 33.Jones R, Haines A. Implementing findings of research. BMJ. 1994;308:1488–92. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6942.1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR). Dissemination self-inventory (version 1). Austin (TX); 1997 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.ncddr.org/du/products/dsi/

- 35.National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR). Dissemination self-inventory (version 2). Austin (TX); 2002 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.ncddr.org/du/products/disseminv/index.html

- 36.National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR). Utilization measurement: focusing on the U in D&U. Austin (TX); 2000 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.ncddr.org/du/products/utilization/

- 37.Canadian Medial Association. Guidelines for Canadian clinical practice guidelines. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Medical Association; 1993.

- 38.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PAC, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A frame work for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hayward RSA, Wilson MC, Tunis SR, Bass EB, Guyatt G. Users’ guides to the medical literature. VIII. How to use clinical practice guidelines. A. Are the recommendations valid? JAMA. 1995;274(7):570–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.274.7.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.US National Commission on Libraries and Information Science (NCLIS). Comprehensive assessment of public information dissemination Jun 2000 – Mar 2001. Washington (DC): NCLIS; 2001. Volumes 1,2,3 & Appendices 1–31. 2001 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.nclis.gov/govt/assess/assess.html

- 41.Selker HP. Criteria for adoption in practice of medical practice guidelines. Am J Cardiol. 1993;71:339–41. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90802-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones LM, Louis KS. Dissemination with impact: what research suggests for practice in career and technical education [academic paper]. Minnesota: University of Minnesota; 1999 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://education.umn.edu/CAREI/Papers/Literature_Rev.rtf

- 43.Grol R, Dalhuijsen J, Thomas S, Veld C, Rutten G, Mokkink H. Attributes of clinical guidelines that influence use of guidelines in general practice: observational study. BMJ. 1998;317:858–61. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7162.858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryder M. Instructional design models. Denver (Colorado): School of Education, University of Colorado at Denver; 2003 Oct [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://carbon.cudenver.edu/~mryder/itc/idmodels.html

- 45.National Center for the Dissemination of Disability Research (NCDDR). Guides to improving practice, number one – improving links between research and practice: approaches to the effective dissemination of disability research. Austin (TX); 1996 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.ncddr.org/du/products/guide1.html

- 46.Harvey K (Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd), Clark RB, Visser S (Drug and Therapeutics Information Service (DATIS)). A mechanism for the development, implementation and evaluation of evidence-based, best-practice clinical guidelines to facilitate quality use of pathology tests. Australia: Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing; 2003 Feb. Tender number: 104/0102 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/haf/branch/dtb/qupcpathg.pdf

- 47.Woolf SH. Practice guidelines: what the family physician should know. Am Fam Physician. 1995;51(6):1455–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.National Center for the Dissemination of Disability Research (NCDDR). Developing an Effective Dissemination Plan. Austin (TX); 2001 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.ncddr.org/du/products/Dissemination.pdf

- 49.Carr R (Level-7 Limited). Information dissemination fundamentals. England: Project Information Prepared for Exploitation and Reference (PIPER), European Commission; 1997. Project #SU 1112(AD) [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://piper.ntua.gr/reports/d11–1.pdf

- 50.IBM. Public health information technology functions and specifications (for emergency preparedness and bioterrorism). IBM main office Armonk (NY): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.ibm.com/ibm/publicaffairs/gp/cdcpaper1.pdf

- 51.Health Policy Forum. Scripting a future for clinical practice guidelines. Proceedings from: a multi-disciplinary summit, Toronto, Jun 5 1999. Montreal (PQ): Merck Frosst; 1999.

- 52.Boland RJ Jr, Singh J, Salipante P, Aram J. Knowledge representations and knowledge transfer [academic paper]. Weatherhead School of Management, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland (OH); 2000 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.aom.pace.edu/amj/April2001/Boland.pdf

- 53.New Zealand Guidelines Group. Template for guideline publishing. New Zealand [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.nzgg.org.nz/development/template.cfm

- 54.Shiffman RN, Shekelle P, Overhage M, Slutsky J, Grimshaw J, Deshpande AM. Standardized reporting of clinical practice guidelines: a proposal from the Conference on Guideline Standardization. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:493–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-6-200309160-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals [updated 2003 Nov; cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://icmje.org

- 56.Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine. Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine Levels of Evidence (May 2001). Headington (Oxford, England): Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, University Department of Psychiatry, Warneford Hospital; 2001 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.cebm.net/levels_of_evidence.asp

- 57.The Steering Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Care and Treatment of Breast Cancer. Introduction. CMAJ. 1998;158(3 Suppl):1s–2s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meltzer S, Leiter L, Daneman D, Gerstein HC, Lau D, Ludwig S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of diabetes in Canada. CMAJ. 1998;159(8 Suppl):1s–29s. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yale JF, Begg I, Gerstein HC, Houlden R, Jones H, Maheux P, et al. 2001 Canadian Diabetes Association clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of hypoglycemia in diabetes. Can J Diabetes. 2001;26(1):22–35. [Google Scholar]

- 60.New South Wales Motor Accidents Authority. Technical report: update Quebec task force guidelines for the management of whiplash-associated disorders. New South Wales (Australia): Motor Accidents Authority; 2001 Jan [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.maa.nsw.gov.au/pdfs/whip_guide_technical.pdf

- 61.Spitzer WO, Skovron ML, Salmi LR, Cassidy JD, Duranceau J, Suissa S, Zeiss E. Scientific Monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders: redefining “whiplash” and its management. Spine. 1995;20(8 Suppl):1s–73s. Erratum in: Spine 1995;20(21):2372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Injury Advisory Committee. The assessment, management and prevention of falls in the elderly in the South Western Sydney Area Health Service. Appendix A, the Injury Advisory Committee terms of reference. Australia: South Western Sydney Area Health Service; 2002 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.swsahs.nsw.gov.au/livtrauma/files/Falls%20in%20the%20Elderly%20%20Appendices.pdf

- 63.Shared Scientific Assessment Committee (SSAC). Pilot shared scientific assessment committee: terms of reference. Australia: Health Ethics Branch, NSW Department of Health; 2002 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/publichealth/rad/Ethics/Sharedassess/pdf/Appendix_2.pdf

- 64.Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. Pregnancy guidelines terms of reference. Australia; 1998 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.hreoc.gov.au/sex_discrimination/pregnancy/guidelines/terms_of_reference.html

- 65.BC Cancer Agency. Clinical Practice Committee terms of reference. British Columbia, Canada: BC Surgical Oncology Council and Network; 2003 [cited 2003 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/NR/rdonlyres/emqnxjirbcu665bg65vrunjkprtdjn7fl2qt33yq2i2ohrriglk2xooazigk43q7wvf6luwpqrjdyb/termsofrefCP.pdf

- 66.Gotlib AC, Injeyan HS, Crawford JP. Laboratory diagnosis in Ontario and the need for reform relative to the profession of chiropractic. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 1997;41(4):205–20. [Google Scholar]