Abstract

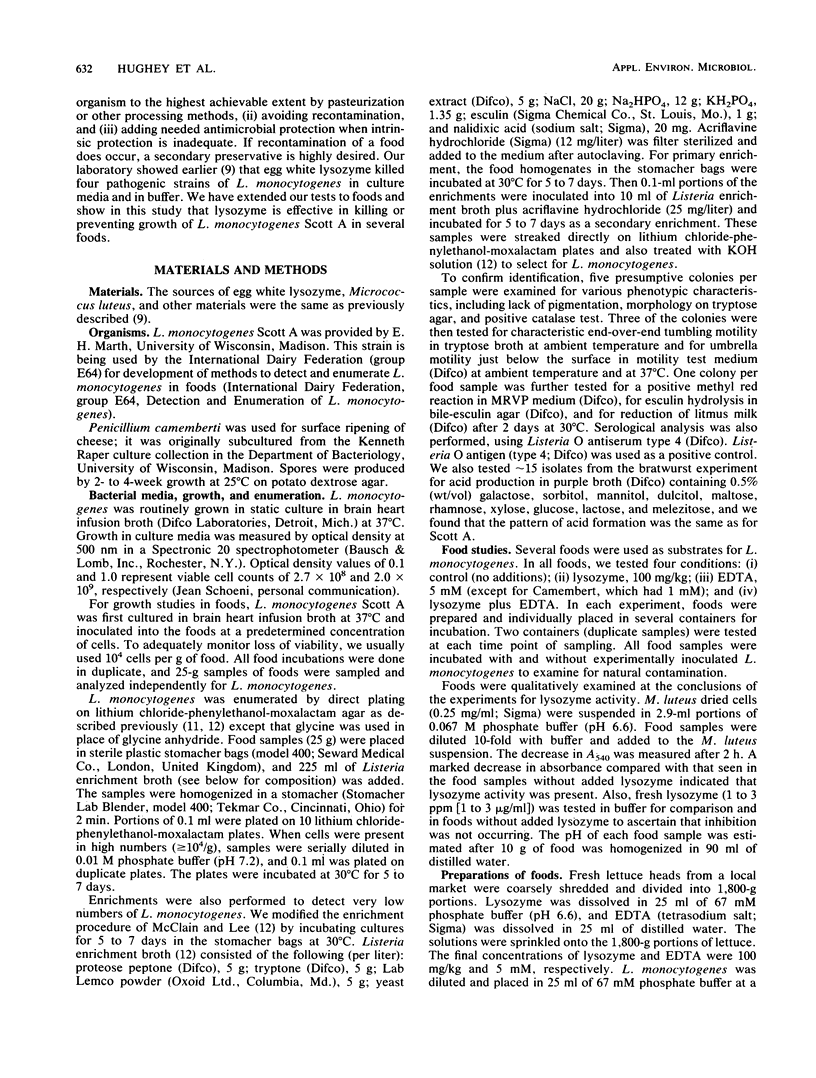

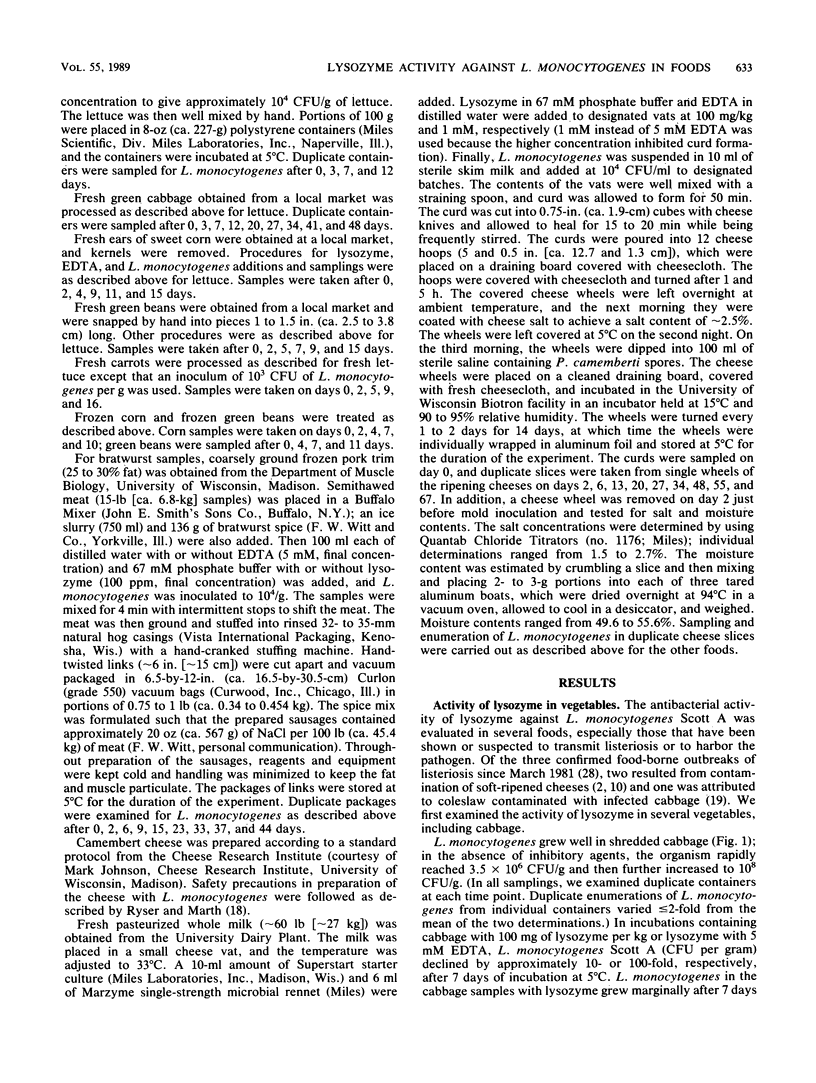

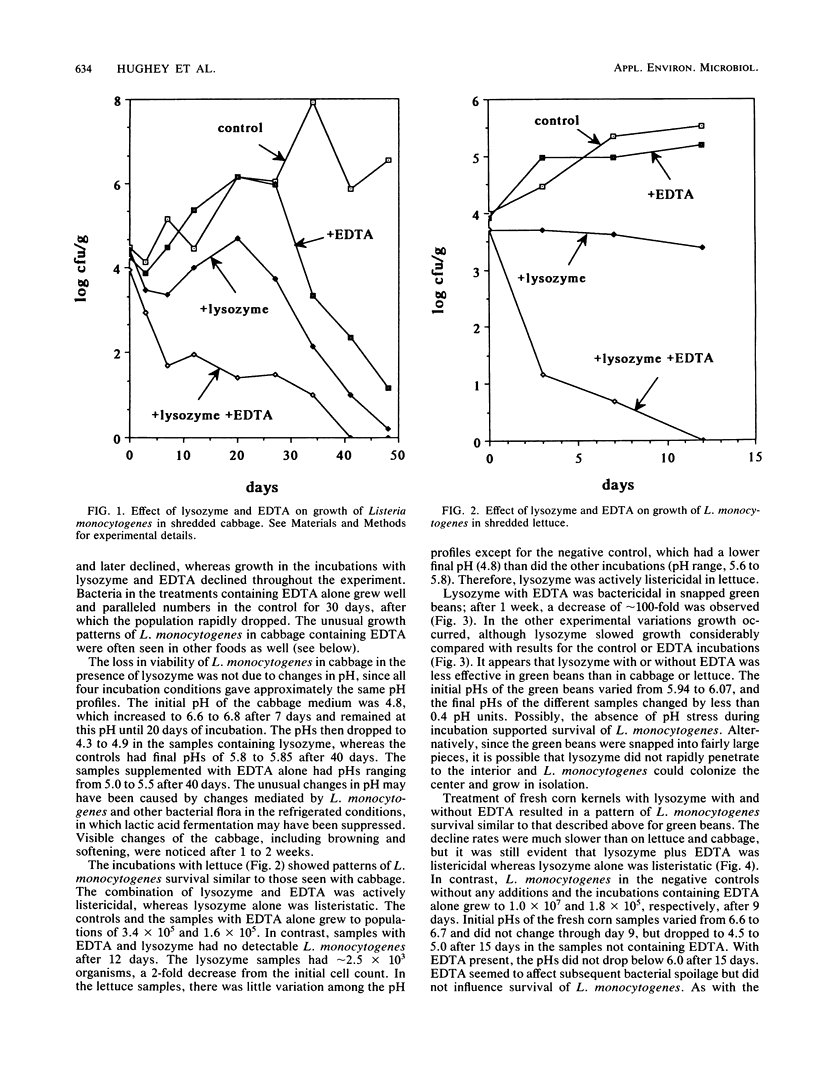

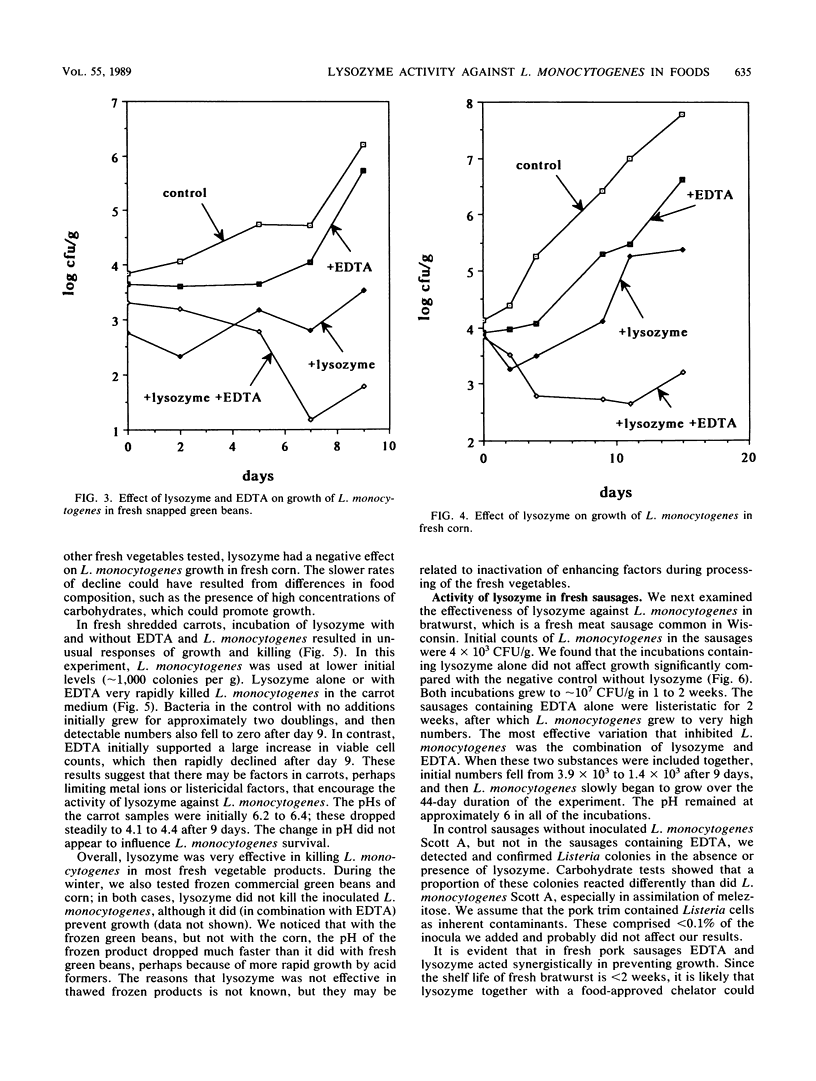

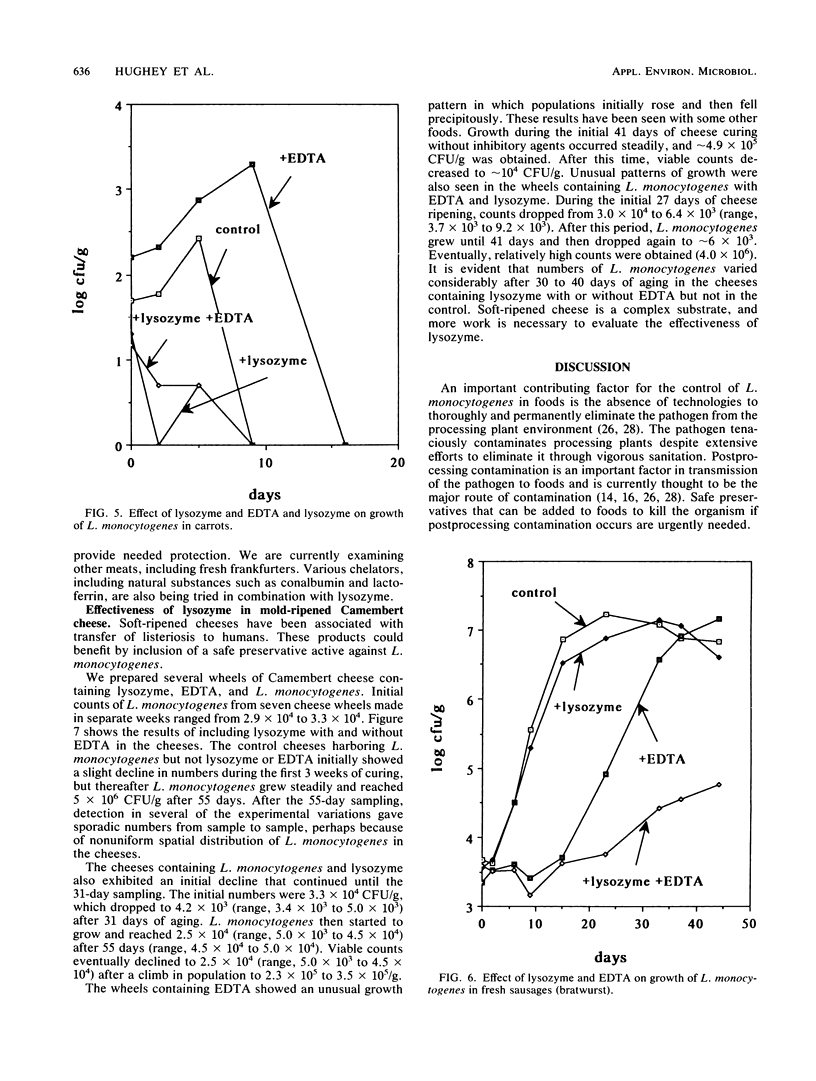

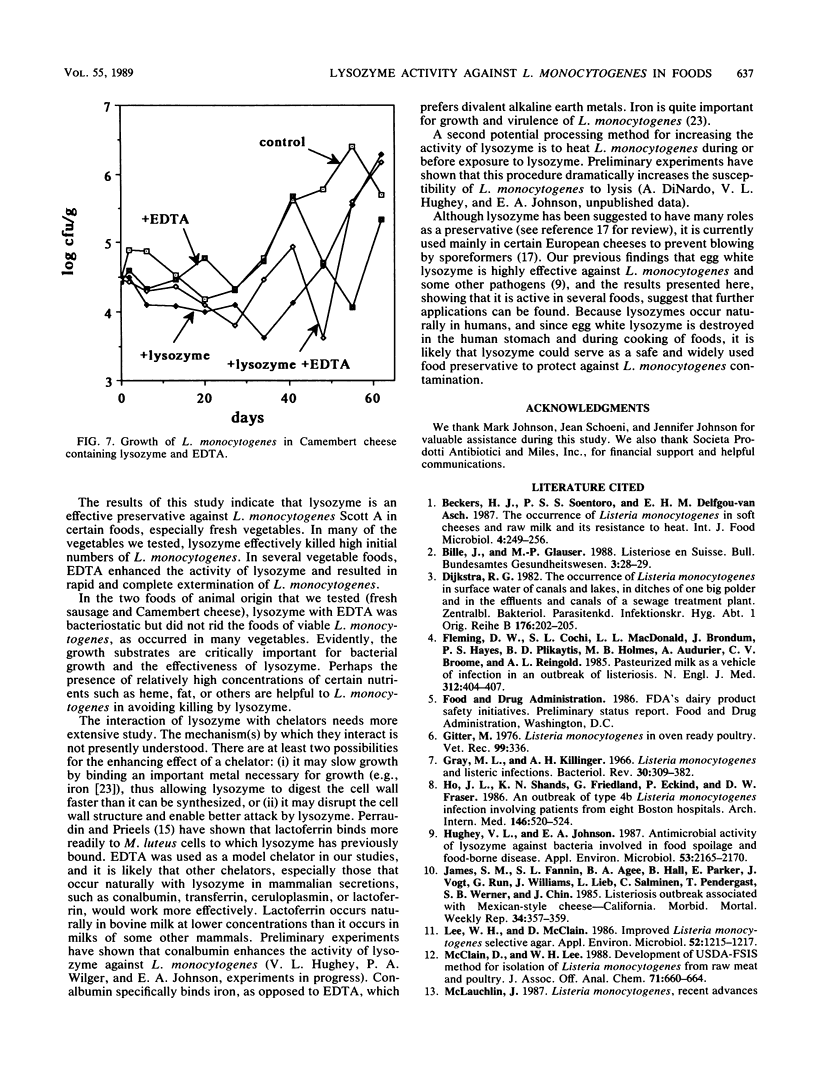

Egg white lysozyme killed or prevented growth of Listeria monocytogenes Scott A in several foods. Lysozyme was more active in vegetables than in animal-derived foods that we tested. For maximum activity in certain foods, EDTA was required in addition to lysozyme. Lysozyme with EDTA effectively killed inoculated populations of 10(4) L. monocytogenes per g in fresh corn, fresh green beans, shredded cabbage, shredded lettuce, and carrots during storage at 5 degrees C. Control incubations without lysozyme supported growth of L. monocytogenes to 10(6) to 10(7)/g. Lysozyme had less activity in animal-derived foods, including fresh pork sausage (bratwurst) and Camembert cheese. In bratwurst, lysozyme with EDTA prevented L. monocytogenes from growing for 2 to 3 weeks but did not kill significant numbers of cells and did not prevent eventual growth. The control sausages not containing lysozyme supported rapid and heavy growth, which indicated that lysozyme was bacteriostatic for 2 to 3 weeks in fresh pork sausage. We also prepared Camembert cheese containing 10(4) L. monocytogenes cells per g and investigated the changes during ripening in cheeses supplemented with lysozyme and EDTA. Cheeses with lysozyme by itself or together with EDTA reduced the L. monocytogenes population by approximately 10-fold over the first 3 to 4 weeks of ripening. In the same period, the control cheese wheels without added lysozyme with and without chelator slowly started to grown and eventually reached 10(6) to 10(7) CFU/g after 55 days of ripening.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 250 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Dijkstra R. G. The occurrence of Listeria monocytogenes in surface water of canals and lakes, in ditches of one big polder and in the effluents and canals of a sewage treatment plant. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg B. 1982 May;176(2-3):202–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming D. W., Cochi S. L., MacDonald K. L., Brondum J., Hayes P. S., Plikaytis B. D., Holmes M. B., Audurier A., Broome C. V., Reingold A. L. Pasteurized milk as a vehicle of infection in an outbreak of listeriosis. N Engl J Med. 1985 Feb 14;312(7):404–407. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198502143120704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitter M. Listeria monocytogenes in "oven-ready" poultry. Vet Rec. 1976 Oct 23;99(17):336–336. doi: 10.1136/vr.99.17.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray M. L., Killinger A. H. Listeria monocytogenes and listeric infections. Bacteriol Rev. 1966 Jun;30(2):309–382. doi: 10.1128/br.30.2.309-382.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho J. L., Shands K. N., Friedland G., Eckind P., Fraser D. W. An outbreak of type 4b Listeria monocytogenes infection involving patients from eight Boston hospitals. Arch Intern Med. 1986 Mar;146(3):520–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughey V. L., Johnson E. A. Antimicrobial activity of lysozyme against bacteria involved in food spoilage and food-borne disease. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987 Sep;53(9):2165–2170. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.9.2165-2170.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W. H., McClain D. Improved Listeria monocytogenes selective agar. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986 Nov;52(5):1215–1217. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.5.1215-1217.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClain D., Lee W. H. Development of USDA-FSIS method for isolation of Listeria monocytogenes from raw meat and poultry. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 1988 May-Jun;71(3):660–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perraudin J. P., Prieels J. P. Lactoferrin binding to lysozyme-treated Micrococcus luteus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982 Sep 17;718(1):42–48. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(82)90007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor V. A., Cunningham F. E. The chemistry of lysozyme and its use as a food preservative and a pharmaceutical. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1988;26(4):359–395. doi: 10.1080/10408398809527473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlech W. F., 3rd, Lavigne P. M., Bortolussi R. A., Allen A. C., Haldane E. V., Wort A. J., Hightower A. W., Johnson S. E., King S. H., Nicholls E. S. Epidemic listeriosis--evidence for transmission by food. N Engl J Med. 1983 Jan 27;308(4):203–206. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198301273080407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sizmur K., Walker C. W. Listeria in prepacked salads. Lancet. 1988 May 21;1(8595):1167–1167. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91983-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sword C. P. Mechanisms of pathogenesis in Listeria monocytogenes infection. I. Influence of iron. J Bacteriol. 1966 Sep;92(3):536–542. doi: 10.1128/jb.92.3.536-542.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tham W. A., Danielsson-Tham V. M. Listeria monocytogenes isolated from soft cheese. Vet Rec. 1988 May 28;122(22):540–540. doi: 10.1136/vr.122.22.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins J., Sleath K. P. Isolation and enumeration of Listeria monocytogenes from Sewage, Sewage Sludge and River Water. J Appl Bacteriol. 1981 Feb;50(1):1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1981.tb00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehr H. M. Listeria monocytogenes--a current dilemma. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 1987 Sep-Oct;70(5):769–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis J., Seeliger H. P. Incidence of Listeria monocytogenes in nature. Appl Microbiol. 1975 Jul;30(1):29–32. doi: 10.1128/am.30.1.29-32.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]