Abstract

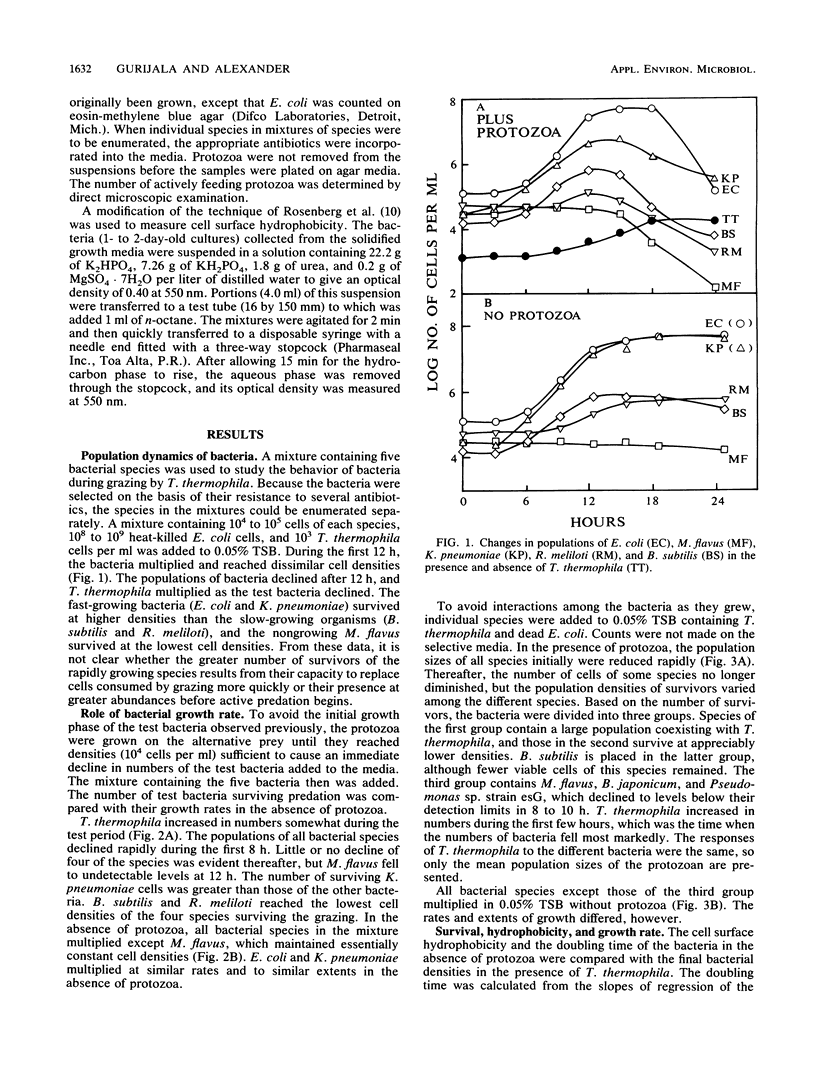

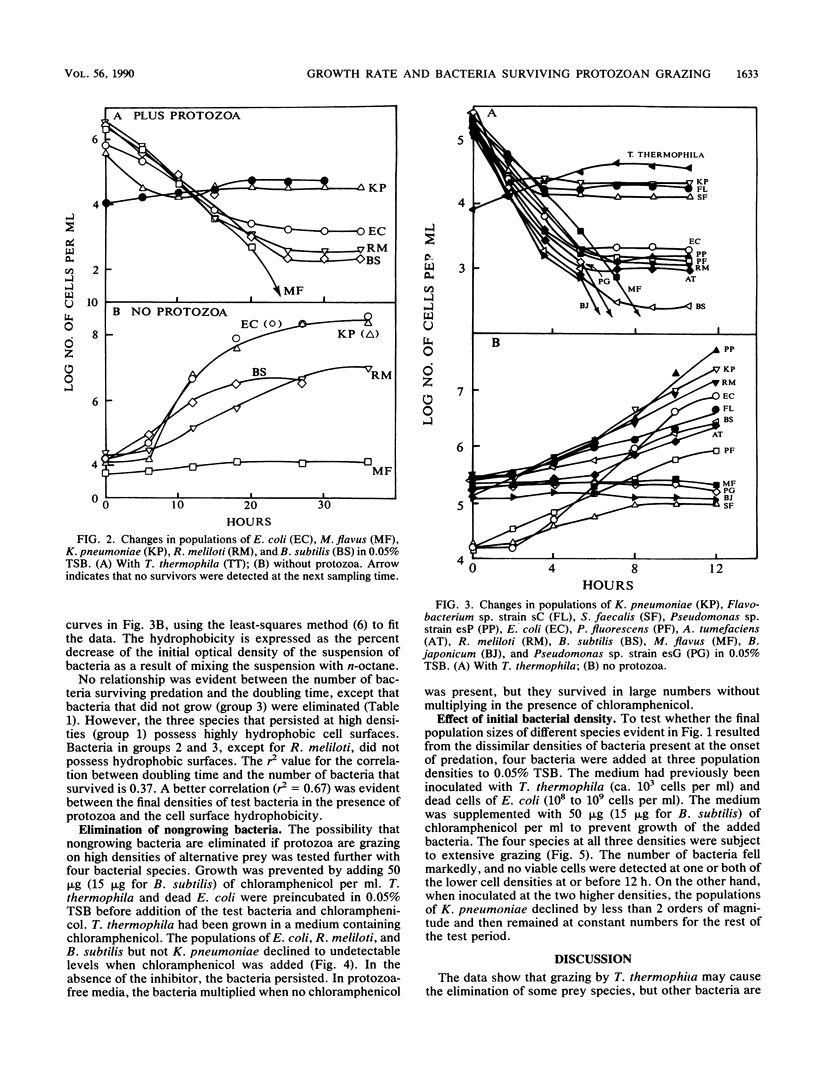

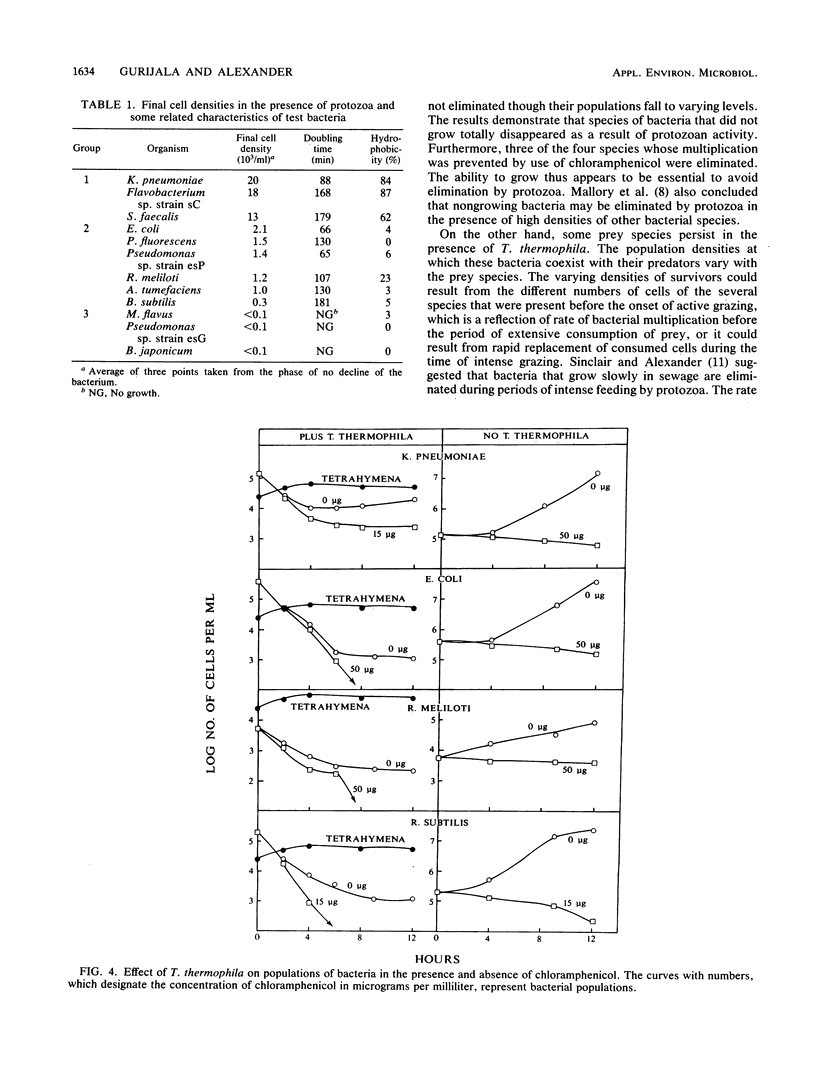

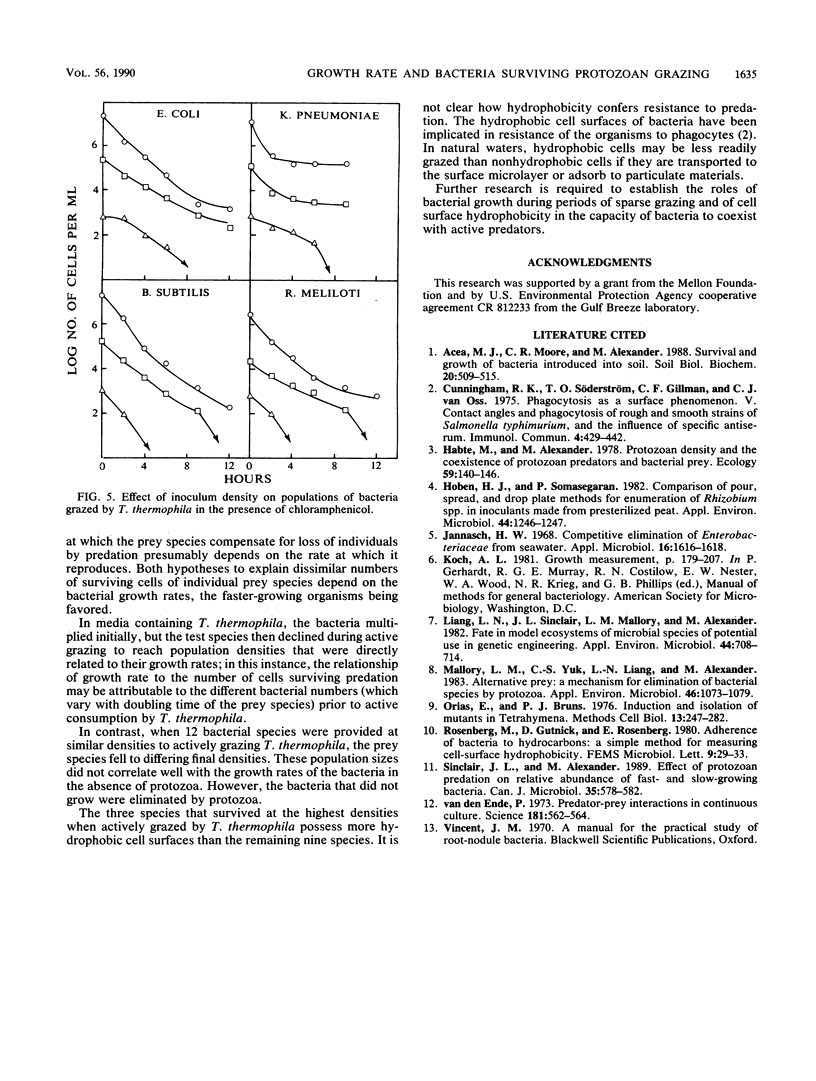

Measurements were made of the predation by Tetrahymena thermophila on several bacterial species in media containing heat-killed Escherichia coli cells to serve as an alternative prey. If grazing pressure was initially not intense on a mixture of bacterial species, the species that survived protozoan feeding at greater densities were those that grew quickly before the onset of active predation. If members of several species were incubated individually at similar initial densities with actively grazing T. thermophila, some species survived at ca. 10(4)/ml, some survived at ca. 10(2)/ml, and others were eliminated. Members of the first two groups but not the third group were able to multiply in the medium in the absence of the protozoan, but the growth rates in the protozoan-free medium did not correlate with the number of survivors. However, the species that persisted at the higher densities possessed highly hydrophobic cell surfaces. The size of the surviving population of four bacterial species whose growth was prevented by chloramphenicol correlated with the initial cell density that was incubated with T. thermophila. It is concluded that the individual species surviving predation on a mixture of species is related to the capacity of the bacterium to grow, the hydrophobicity of its cell surface, and the population density of the species before the onset of intense grazing.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Cunningham R. K., Söderström T. O., Gillman C. F., van Oss C. J. Phagocytosis as a surface phenomenon. V. Contact angles and phagocytosis of rough and smooth strains of Salmonella typhimurium, and the influence of specific antiserum. Immunol Commun. 1975;4(5):429–442. doi: 10.3109/08820137509057331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoben H. J., Somasegaran P. Comparison of the Pour, Spread, and Drop Plate Methods for Enumeration of Rhizobium spp. in Inoculants Made from Presterilized Peat. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982 Nov;44(5):1246–1247. doi: 10.1128/aem.44.5.1246-1247.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jannasch H. W. Competitive elimination of Enterobacteriaceae from seawater. Appl Microbiol. 1968 Oct;16(10):1616–1618. doi: 10.1128/am.16.10.1616-1618.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang L. N., Sinclair J. L., Mallory L. M., Alexander M. Fate in model ecosystems of microbial species of potential use in genetic engineering. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982 Sep;44(3):708–714. doi: 10.1128/aem.44.3.708-714.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallory L. M., Yuk C. S., Liang L. N., Alexander M. Alternative prey: a mechanism for elimination of bacterial species by protozoa. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983 Nov;46(5):1073–1079. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.5.1073-1079.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orias E., Bruns P. J. Induction and isolation of mutants in Tetrahymena. Methods Cell Biol. 1976;13:247–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Ende P. Predator-prey interactions in continuous culture. Science. 1973 Aug 10;181(4099):562–564. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4099.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]