Abstract

The discovery of sequence homology between the cytoplasmic domains of Drosophila Toll and human interleukin 1 receptors has sown the conviction that both molecules trigger related signaling pathways tied to the nuclear translocation of Rel-type transcription factors. This conserved signaling scheme governs an evolutionarily ancient immune response in both insects and vertebrates. We report the molecular cloning of a class of putative human receptors with a protein architecture that is similar to Drosophila Toll in both intra- and extracellular segments. Five human Toll-like receptors—named TLRs 1–5—are probably the direct homologs of the fly molecule and, as such, could constitute an important and unrecognized component of innate immunity in humans. Intriguingly, the evolutionary retention of TLRs in vertebrates may indicate another role—akin to Toll in the dorsoventralization of the Drosophila embryo—as regulators of early morphogenetic patterning. Multiple tissue mRNA blots indicate markedly different patterns of expression for the human TLRs. By using fluorescence in situ hybridization and sequence-tagged site database analyses, we also show that the cognate Tlr genes reside on chromosomes 4 (TLRs 1, 2, and 3), 9 (TLR4), and 1 (TLR5). Structure prediction of the aligned Toll-homology domains from varied insect and human TLRs, vertebrate interleukin 1 receptors and MyD88 factors, and plant disease-resistance proteins recognizes a parallel β/α fold with an acidic active site; a similar structure notably recurs in a class of response regulators broadly involved in transducing sensory information in bacteria.

The seeds of the morphogenetic gulf that so dramatically separates flies from humans are planted in familiar embryonic shapes and patterns but give rise to very different cell complexities (1, 2). This divergence of developmental plans between insects and vertebrates is choreographed by remarkably similar signaling pathways, underscoring a greater conservation of protein networks and biochemical mechanisms from unequal gene repertoires (3, 4). A powerful way to chart the evolutionary design of these regulatory pathways is by inferring their likely molecular components (and biological functions) through interspecies comparisons of protein sequences and structures (3–5).

A universally critical step in embryonic development is the specification of body axes, either born from innate asymmetries or triggered by external cues (1, 2). As a model system, particular attention has been focused on the phylogenetic basis and cellular mechanisms of dorsoventral polarization (1, 2). A prototype molecular strategy for this transformation has emerged from the Drosophila embryo, where the sequential action of a small number of genes results in a ventralizing gradient of the transcription factor Dorsal (6, 7). This signaling pathway centers on Toll, a transmembrane receptor that transduces the binding of a maternally secreted ventral factor, Spätzle, into the cytoplasmic engagement of Tube, an accessory molecule, and the activation of Pelle, a Ser/Thr kinase that catalyzes the dissociation of Dorsal from the inhibitor Cactus and allows migration of Dorsal to ventral nuclei (7, 8). The Toll pathway also controls the induction of potent antimicrobial factors in the adult fly (9); this role in Drosophila immune defense strengthens mechanistic parallels to interleukin 1 (IL-1) pathways that govern a host of immune and inflammatory responses in vertebrates (8, 10). A Toll-related cytoplasmic domain in IL-1 receptors (IL-1Rs) directs the binding of a Pelle-like kinase, IRAK, and the activation of a latent NF-κB/I-κB complex that mirrors the embrace of Dorsal and Cactus (8, 10).

We describe the cloning and molecular characterization of five Toll-like molecules in humans—named TLRs 1–5 [as in Chiang and Beachy (11)]—that reveal a receptor family more closely tied to Drosophila Toll homologs than to vertebrate IL-1Rs. The TLR sequences are derived from human expressed sequence tags (ESTs); these partial cDNAs were used to draw complete expression profiles in human tissues for the five TLRs, map the chromosomal locations of cognate genes, and narrow the choice of cDNA libraries for full-length cDNA retrievals. Spurred by other efforts (5, 12), we are assembling, by structural conservation and molecular parsimony, a biological system in humans that is the counterpart of a compelling regulatory scheme in Drosophila. In addition, a biochemical mechanism driving Toll signaling is suggested by the proposed tertiary fold of the Toll-homology (TH) domain, a core module shared by TLRs, a broad family of IL-1Rs, mammalian MyD88 factors, and plant disease-resistance proteins (13, 14). We propose that a signaling route coupling morphogenesis and primitive immunity in insects, plants, and animals (8, 15) may have roots in bacterial two-component pathways.†

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Computational Analysis.

Human sequences related to insect TLRs were harvested from the EST database (dbEST) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information by using the BLAST server with the Gonnet protein comparison matrix (16). More sensitive pattern- and profile-based methods (17) were used to isolate the signaling domains of the TLR family that are shared with vertebrate and plant proteins present in nonredundant databases. The progressive alignment of TLR intra- or extracellular domain sequences was carried out by clustalw (18); this program also calculated the branching order of aligned sequences by the neighbor-joining algorithm (10,000 bootstrap replications provided confidence values for the tree groupings).

Conserved alignment patterns were drawn by the consensus program (internet URL http://www.bork.embl-heidelberg.de/Alignment/consensus.html). The PRINTS library of protein fingerprints (http://www.biochem.ucl.ac.uk/bsm/dbbrowser/PRINTS/PRINTS.html) (19) reliably identified the myriad leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) present in the extracellular segments of TLRs with a compound “Leurichrpt” motif that flexibly matches N- and C-terminal features of divergent LRRs. Two algorithms whose three-state accuracy is greater than 72%—the neural network program phd (20) and the statistical prediction method dsc (21)—were used to derive a consensus secondary structure for the TH domain alignment. Fold recognition efforts (for reviews, see refs. 20, 22, and 23) used programs such as profit, 123d and rdp within toplign (http://cartan.gmd.de/ToPLign.html) to “thread” sequences through protein-fold databases with empirically derived potentials; secondary structure information is assimilated by h3p2 (http://foldserver.mbi.ucla.edu), pscan (http://www.biokemi.su.se/~arne/pscan), and topits to best “map” sequence to structure; domain-fold databases encompassed 300 (profit), 347 (pscan), 1302 (toplign), and 1,634 (h3p2) structures.

Cloning of Full-Length Human TLR cDNAs.

PCR primers derived from the Toll-like Humrsc786 sequence (GenBank accession no. D13637) (24) were used to probe a human erythroleukemic TF-1 cell line-derived cDNA library (25) to yield the TLR1 cDNA sequence. The remaining TLR sequences were flagged from dbEST, and the relevant EST clones were obtained from the I.M.A.G.E. consortium (26) via Research Genetics (Huntsville, AL); clone identification nos. are as follows: 80633 and 117262, TLR2; 144675, TLR3; 202057, TLR4; 277229, TLR5. Full-length cDNAs for human TLRs 2–4 were cloned by DNA hybridization screening of λgt10 phage and human adult lung, placenta, and fetal liver 5′ Stretch Plus cDNA libraries (CLONTECH), respectively; the TLR5 sequence is derived from a human multiple sclerosis plaque EST. All positive clones were sequenced and aligned to identify individual TLR ORFs as follows: TLR1 (2,366-bp clone, 786-aa ORF), TLR2 (2,600-bp clone, 784-aa ORF), TLR3 (3,029-bp clone, 904-aa ORF), TLR4 (3,811-bp clone, 879-aa ORF), and TLR5 (1,275-bp clone, 370-aa ORF). Probes for TLR3 and TLR4 hybridizations were generated by PCR using human placenta (Stratagene) and adult liver (CLONTECH) cDNA libraries as templates, respectively; primer pairs were derived from the respective EST sequences. PCRs were conducted with Thermus aquaticus Taqplus DNA polymerase (Stratagene) under the following conditions: 1× (94°C, 2 min), 30× (55°C, 20 sec; 72°C, 30 sec; 94°C, 20 sec), and 1× (72°C, 8 min). For TLR2 full-length cDNA screening, a 900-bp fragment generated by EcoRI/XbaI digestion of the first EST clone (indentification no. 80633) was used as a probe.

mRNA Blots and Chromosomal Localization.

Human multiple tissue (catalog nos. 7759 and 7760) and cancer cell line blots (catalog numbers 7757–1), containing approximately 2 μg of poly(A)+ RNA per lane, were purchased from CLONTECH. For TLRs 1–4, the isolated full-length cDNAs served as probes; for TLR5, the EST clone (indentification no. 277229) plasmid insert was used. Briefly, the probes were radiolabeled with [α32-P]dCTP by using the Amersham Rediprime random primer labeling kit (product RPN1633). Prehybridization and hybridizations were performed at 65°C in 0.5 M Na2HPO4/7% SDS/0.5 M EDTA, pH 8.0. All stringency washes were conducted at 65°C with two initial washes in 2× SSC/0.1% SDS for 40 min, followed by a subsequent wash in 0.1× SSC/0.1% SDS for 20 min. Membranes were then exposed at −70°C to x-ray film (Kodak) in the presence of intensifying screens. More detailed studies with cDNA library Southern blots (14) were performed with selected human TLR clones to examine their expression in hemopoietic cell subsets (data not shown).

Human chromosomal mapping was conducted by the method of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) as described (27) using the various full-length (TLRs 2–4) or partial (TLR5) cDNA clones as probes. These analyses were performed as a service by SeeDNA Biotech (Ontario, Canada). A search for human syndromes (or mouse defects in syntenic loci) associated with the mapped TLR genes was conducted in the Dysmorphic Human–Mouse Homology Database by an internet server (http://www.hgmp.mrc.ac.uk/DHMHD/hum_chrome1.html).

RESULTS

Conserved Architecture of Insect and Human TLR Ectodomains.

The Toll family in Drosophila comprises at least four distinct gene products: Toll, the prototype receptor involved in dorsoventral patterning of the fly embryo (7), a second receptor named 18 Wheeler (18w) that also may be involved in early embryonic development (11, 28), and two additional receptors are predicted by incomplete Toll-like ORFs downstream of the male-specific-transcript (Mst) locus (GenBank accession no. X67703) or encoded by the sequence-tagged site (STS) Dm2245 (GenBank accession no. G01378) (13). The extracellular segments of Toll and 18w are distinctively composed of imperfect ∼24-amino acid LRR motifs (11, 28). Similar tandem arrays of LRRs commonly form the adhesive antennae of varied cell surface molecules and their generic tertiary structure is presumed to mimic the horseshoe-shaped cradle of a ribonuclease inhibitor fold, where 17 LRRs show a repeating β/α-hairpin 28-residue motif (29). The specific recognition of Spätzle by Toll may follow a model proposed for the binding of cystine-knot fold glycoprotein hormones by the multi-LRR ectodomains of serpentine receptors, by using the concave side of the curved β-sheet (30); intriguingly, the pattern of cysteines in Spätzle and an orphan Drosophila ligand, Trunk, predict a similar cystine-knot tertiary structure (8, 31).

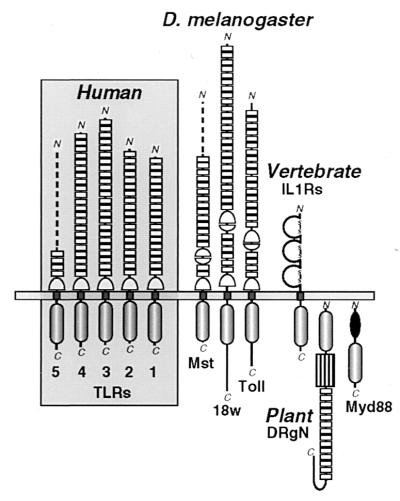

The 22- and 31-LRR ectodomains of Toll and 18w, respectively (the Mst ORF fragment displays 16 LRRs), are most closely related to the comparable 18-, 19-, 24-, and 22-LRR arrays of TLRs 1–4 (the incomplete TLR5 chain presently includes four membrane-proximal LRRs) by sequence and pattern analysis (16, 17) (Fig. 1). However, a striking difference in the human TLR chains is the common loss of a ∼90-residue cysteine-rich region that is variably embedded in the ectodomains of Toll, 18w, and the Mst ORF (distanced 4, 6, and 2 LRRs, respectively, from the membrane boundary). These cysteine clusters are bipartite, with distinct top (ending an LRR) and bottom (stacked atop an LRR) halves (11, 28, 29); the top module recurs in both Drosophila and human TLRs as a conserved juxtamembrane spacer (Fig. 1). We suggest that the flexibly located cysteine clusters in Drosophila receptors (and other LRR proteins)—when mated top to bottom—form a compact module with paired termini that can be inserted between any pair of LRRs without altering the overall fold of TLR ectodomains; analogous extruded domains decorate the structures of other proteins (32).

Figure 1.

Schematic comparison of the protein architectures of Drosophila and human TLRs and their relationship to vertebrate IL-1Rs and plant disease-resistance proteins. Three Drosophila (Dm) TLRs (Toll, 18w, and the Mst ORF fragment) (7, 11, 13, 28) are arrayed beside the four complete (TLRs 1–4) and one partial (TLR5) human (Hu) receptors. Individual LRRs in the receptor ectodomains that are flagged by PRINTS (19) are explicitely noted by boxes; top and bottom Cys-rich clusters that flank the C- or N-terminal ends of LRR arrays are respectively drawn by apposed half circles. The loss of the internal Cys-rich region in TLRs 1–5 largely accounts for their smaller ectodomains (558, 570, 690 and 652 aa, respectively) when compared with the 784- and 977-aa extensions of Toll and 18w. The incomplete chains of DmMst and HuTLR5 (519- and 153-aa ectodomains, respectively) are represented by dashed lines. The intracellular signaling module common to TLRs, IL-1Rs, the intracellular protein Myd88, and the tobacco disease-resistance gene N product (DRgN) is indicated below the membrane. Additional domains include the trio of Ig-like modules in IL-1Rs (disulfide-linked loops); the DRgN protein features a nucleotide-binding domain (box) and Myd88 has a death domain (solid oval).

Molecular Design of the TH Signaling Domain.

Sequence comparison of Toll and IL-1R type I (IL-1R1) has disclosed a distant resemblance of an ∼200-amino acid cytoplasmic domain that presumably mediates signaling by similar Rel-type transcription factors (8, 10). More recent additions to this functional paradigm include four plant disease-resistance proteins from tobacco, thale cress, and flax that feature an N-terminal TH module followed by nucleotide-binding and LRR segments (15); by contrast, a death domain preceeds the TH chain of MyD88, an intracellular myeloid differentiation marker (13, 14) (Fig. 1). Additional IL-1R-type receptors include IL-1R3, an accessory signaling molecule, and orphan receptors IL-1R4 (also called ST2/Fit-1/T1), IL-1R5 (IL-1R-related protein), and IL-1R6 (IL-1R-related protein 2) (13, 14). With the new human TLR sequences, we have sought a structural definition of this evolutionary thread by analyzing the conformation of the common TH module: 10 blocks of conserved sequence containing 128 amino acids form the minimal TH domain fold; gaps in the alignment mark the likely location of sequence- and length-variable loops (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Conserved structural patterns in the signaling domains of Toll- and IL-1-like cytokine receptors and two divergent modular proteins. (A) Sequence alignment of the common TH domain. TLRs are labeled as in Fig. 1; the human (Hu) or mouse (Mo) IL-1 family receptors (IL-1R1–6) are sequentially numbered as proposed (14); Myd88 and the disease-resistance protein (DRP) sequences from tobacco (To), Arabidopsis thaliana (At), and Linum usitatissimum (Lu) represent C- and N-terminal domains, respectively, of larger multidomain molecules. Ungapped blocks of sequence (numbered 1–10) are boxed. Triangles indicate deleterious mutations, and truncations N-terminal of the arrow eliminate bioactivity in human IL-1R1 (33). phd (20) and dsc (21) secondary structure predictions of α-helix (H), β-strand (E), or coil (L) are marked. The amino acid coloring scheme depicts chemically similar residues: green (hydrophobic), red (acidic), blue (basic), yellow (Cys), orange (aromatic), black (structure breaking), and grey (tiny). Diagnostic sequence patterns for IL-1Rs, TLRs, DRPs, and full alignment (ALL) were derived by consensus at a stringency of 75%. Symbols for amino acid subsets are as follows (see consensus site for detail): o, alcohol; l, aliphatic; a dot, any amino acid; a, aromatic; c, charged; h, hydrophobic; −, negative; p, polar; +, positive; s, small; u, tiny; t, turnlike. (B) Topology diagram of the proposed CheY-like TH β/α domain fold. Parallel β-sheets (with β-strands A–E as yellow triangles) are seen at their C-terminal ends; α-helices (red circles labeled 1–5) link the β-strands; chain connections are to the front (visible) or back (hidden). Conserved charged residues at the C-terminal end of the β-sheets are noted in a shaded (Asp) or black (Arg) circle (see text).

Two prediction algorithms that take advantage of the patterns of conservation and variation in multiply aligned sequences, phd (20) and dsc (21), produced strong concordant results for the TH signaling module (Fig. 2A). Each block contains a discrete secondary structural element: the imprint of alternating β-strands (labeled A–E) and α-helices (numbered 1–5) is diagnostic of an β/α-class fold with α-helices on both faces of a parallel β-sheet. Hydrophobic β-strands A, C, and D are predicted to form interior staves in the β-sheet, whereas the shorter amphipathic β-strands B and E resemble typical edge units (Fig. 2A). This assignment is consistent with a strand order of B–A–C–D–E in the core β-sheet (Fig. 2B); fold comparison (mapping) and recognition (threading) programs (20, 22, 23) strongly return this doubly wound β/α topology (see Discussion). A surprising functional prediction of this outline structure for the TH domain is that many of the conserved charged residues in the multiple alignment map to the C-terminal end of the β-sheet: residue Asp-16 (Fig. 2A, block numbering scheme) at the end of βA, Arg-39 and Asp-40 after βB, Glu-75 in the first turn of α3, and the more loosely conserved Glu/Asp residues in the βD-α4 loop or after βE (Fig. 2A). Four other conserved residues (Asp-7, Glu-28, and the Arg-57–Arg/Lys-58 pair) form an epitope at the opposite N-terminal end of the β-sheet (Fig. 2A).

Signaling function depends on the structural integrity of the TH domain. Inactivating mutations or deletions within the module boundaries (Fig. 2A) have been catalogued for IL-1R1 and Toll (33–38). The human TLR1–5 chains extending past the minimal TH domain (8-, 0-, 6-, 22-, and 18-residue lengths, respectively) are most closely similar to the stubby, 4-aa tail of the Mst ORF. Toll and 18w display unrelated 102- and 207-residue tails (Fig. 2A) that may negatively regulate the signaling of their TH domains (37, 38).

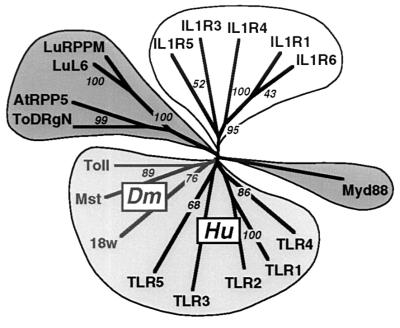

The evolutionary relationship between the disparate proteins that carry the TH domain can best be discerned by a phylogenetic tree derived from the multiple alignment (18) (Fig. 3). Four principal branches segregate the plant proteins, the MyD88 factors, IL-1Rs, and Toll-like molecules; the latter branch decidedly clusters the Drosophila and human TLRs.

Figure 3.

Evolution of a signaling domain superfamily. The multiple TH module alignment of Fig. 2 was used to derive a phylogenetic tree by the neighbor-joining method (18); 10,000 bootstrapping replications were conducted to assess the reliability of the branching patterns (noted at selected nodes as percents). Proteins are labeled as in the alignment; the tree was rendered with treeview.

Chromosomal Dispersal of Human TLR Genes.

To investigate the genetic linkage of the nascent human Tlr gene family, we mapped the chromosomal loci of four of the five genes by FISH (Fig. 4). The Tlr1 gene has been charted by the human genome project: an STS database locus (dbSTS accession no. G06709, corresponding to STS WI-7804 or SHGC-12827) exists for the Humrsc786 cDNA (24) and fixes the gene to chromosome 4 marker interval D4S1587–D42405 (50–56 centimorgans) about 4p14. This assignment has recently been corroborated by FISH analysis (39). In the present work, we reliably assign the remaining Tlr genes to loci on chromosomes 4q32 (TLR2), 4q35 (TLR3), 9q32–33 (TLR4), and 1q33.3 (TLR5). During the course of this work, an STS for the parent TLR2 EST (clone identification no. 80633) has been generated (dbSTS accession no. T57791 for STS SHGC-33147) and maps to the chromosome 4 marker interval D4S424–D4S1548 (143–153 centimorgans) at 4q32—in accord with our findings. There is a ∼50-centimorgan gap between Tlr2 and Tlr3 genes on the long arm of chromosome 4.

Figure 4.

FISH chromosomal mapping of human TLR genes. Denatured chromosomes from synchronous cultures of human lymphocytes were hybridized to biotinylated TLR cDNA probes for localization. (A) TLR2. (B) TLR3. (C) TLR4. (D) TLR5. Assignment of the FISH mapping data (Left) with chromosomal bands was achieved by superimposing FISH signals with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole-banded chromosomes (Center) (27). Analyses are summarized in the form of human chromosome ideograms (Right).

Tlr Genes Are Differentially Expressed.

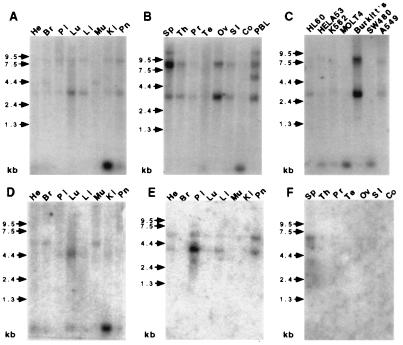

Both Toll and 18w have complex spatial and temporal patterns of expression in Drosophila that may point to functions beyond embryonic patterning (6–9, 11, 28). We have examined the spatial distribution of TLR transcripts by mRNA blot analysis with varied human tissue and cancer cell lines by using radiolabeled TLR cDNAs (Fig. 5). TLR1 is found to be expressed ubiquitously and at higher levels than the other receptors. Short 3.0-kb and long 8.0-kb TLR1 transcript forms are present in ovary and spleen, respectively (Fig. 5 A and B), presumably reflecting alternative splicing. A cancer-cell mRNA panel also shows the prominent overexpression of TLR1 in a Burkitt’s lymphoma Raji cell line (Fig. 5C). TLR2 mRNA is less widely expressed than TLR1, with a 4.0-kb species detected in lung and a 4.4-kb transcript evident in heart, brain, and muscle. The tissue distribution pattern of TLR3 echoes that of TLR2 (Fig. 5E). TLR3 is also present as two major transcripts of approximately 4.0 and 6.0 kB in size, and the highest levels of expression are observed in placenta and pancreas. By contrast, TLR4 and TLR5 messages appear to be extremely tissue-specific. TLR4 was detected only in placenta as a single transcript of ∼7.0 kb. A faint 4.0-kb signal was observed for TLR5 in ovary and peripheral blood monocytes (data not shown).

Figure 5.

mRNA blot analyses of human TLRs. Human multiple tissue blots (He, heart; Br, brain; Pl, placenta; Lu, lung; Li, liver; Mu, muscle; Ki, kidney; Pn, Pancreas; Sp, spleen; Th, thymus; Pr, prostate; Te, testis; Ov, ovary, SI, small intestine; Co, colon; PBL, peripheral blood lymphocytes) and cancer cell line (promyelocytic leukemia, HL60; cervical cancer, HELAS3; chronic myelogenous leukemia, K562; lymphoblastic leukemia, Molt4; colorectal adenocarcinoma, SW480; melanoma, G361; Burkitt lymphoma Raji, Burkitt’s; colorectal adenocarcinoma, SW480; lung carcinoma, A549) containing approximately 2 μg of poly(A)+ RNA per lane were probed with radiolabeled cDNAs encoding TLR1 (A–C), TLR2 (D), TLR3 (E), and TLR4 (F). Blots were exposed to x-ray film for 2 days (A–C) or 1 week (D–F) at −70°C with intensifying screens. An anomalous 0.3-kb species appears in some lanes; hybridization experiments exclude a message encoding a TLR cytoplasmic fragment.

DISCUSSION

Components of an Evolutionarily Ancient Regulatory System.

The original molecular blueprints and divergent fates of signaling pathways can be reconstructed by comparative genomic approaches (3–5, 12). We have used this logic to identify an emergent gene family in humans—encoding five receptor paralogs at present, TLRs 1–5—that are the direct evolutionary counterparts of a Drosophila gene family headed by Toll (Figs. 1–3). The conserved architecture of human and fly TLRs—conserved LRR ectodomains and intracellular TH modules (Fig. 1)—intimates that the robust pathway coupled to Toll in Drosophila (6, 7) survives in vertebrates. The best evidence borrows from a reiterated pathway, the manifold IL-1 system and its repertoire of receptor-fused TH domains, IRAK, NF-κB, and I-κB homologs (8, 10, 14, 40). It is not known whether TLRs can productively couple to the IL-1R signaling machinery or whether a parallel set of proteins is used. Differently from IL-1Rs, the LRR cradle of human TLRs is predicted to retain an affinity for Spätzle/Trunk-related cystine-knot factors; candidate TLR ligands (called PENs) that fit this mold have been isolated (R.A.K., unpublished results).

Biochemical mechanisms of signal transduction can be gauged by the conservation of interacting protein folds in a pathway (3, 4). At present, the Toll signaling paradigm involves some molecules whose roles are narrowly defined by their structures, actions, or fates: Pelle is a Ser/Thr kinase (phosphorylation), Dorsal is an NF-κB-like transcription factor (DNA binding), and Cactus is an ankyrin-repeat inhibitor (Dorsal binding and degradation) (8). By contrast, the functions of the Toll TH domain and Tube remain enigmatic. Like other cytokine receptors (41), ligand-mediated dimerization of Toll appears to be the triggering event: free cysteines in the juxtamembrane region of Toll create constitutively active receptor pairs (35), and chimeric Torso-Toll receptors signal as dimers (42); yet, severe truncations or wholesale loss of the Toll ectodomain results in promiscuous intracellular signaling (37, 43)—reminiscent of oncogenic receptors with catalytic domains (41). Tube is membrane-localized, engages the N-terminal (death) domain of Pelle, and is phosphorylated, but neither Toll–Tube or Toll–Pelle interactions are registered by two-hybrid analysis (42, 44); this latter result suggests that the conformational state of the Toll TH domain somehow affects factor recruitment (38, 42).

At the heart of these vexing issues is the structural nature of the Toll TH module. To address this question, we have taken advantage of the evolutionary diversity of TH sequences from insects, plants, and vertebrates—incorporating the human TLR chains—and extracted the minimal conserved protein core for structure prediction and fold recognition (Fig. 2). The strongly predicted (β/α)5 TH domain fold with its asymmetric cluster of acidic residues is topologically identical to the structures of response regulators in bacterial two-component signaling pathways (45, 46) (Fig. 2). The prototype chemotaxis regulator CheY transiently binds a divalent cation in an aspartate pocket at the C-terminal end of the core β-sheet; this cation provides electrostatic stability and facilitates the activating phosphorylation of an invariant Asp (45). Likewise, the TH domain may capture cations in its acidic nest, but activation—and downstream signaling—could depend on the specific binding of a negatively charged moiety: anionic ligands can overcome intensely negative binding-site potentials by locking into precise hydrogen-bond networks (47). Intriguingly, the TH domain may not simply act as a passive scaffold for the assembly of a Tube–Pelle complex for Toll—or homologous systems in plants and vertebrates—but, instead, actively participate as a true conformational trigger in the signal transducing machinery. Toll dimerization could promote unmasking by regulatory receptor tails (37, 38), or binding of the TH pocket by small molecule activators, perhaps explaining the conditional binding of a Tube–Pelle complex. However, free TH modules inside the cell (37, 43) could act as catalytic CheY-like triggers by activating and docking with errant Tube–Pelle complexes.

Morphogenetic Receptors and Immune Defense.

The evolutionary link between insect and vertebrate immune systems is stamped in DNA: genes encoding antimicrobial factors in insects display upstream motifs similar to acute-phase response elements known to bind NF-κB transcription factors in mammals (48). Dorsal and two Dorsal-related factors, Dif and Relish, help induce these defense proteins after bacterial challenge (49–51); Toll or other TLRs probably modulate these rapid immune responses in adult Drosophila (9, 52). These mechanistic parallels to the IL-1 inflammatory response in vertebrates are evidence of the functional versatility of the Toll signaling pathway and suggest an ancient synergy between embryonic patterning and innate immunity (8–10, 15, 48–53). The closer homology of insect and human TLR proteins invites an even stronger overlap of biological functions that supersedes the purely immune parallels to IL-1 systems and lends potential molecular regulators to dorsoventral and other transformations of vertebrate embryos (1, 2).

The present description of an emergent robust receptor family in humans mirrors the recent discovery of the vertebrate Frizzled receptors for Wnt patterning factors (12). As numerous other cytokine receptor systems have roles in early development (54), perhaps the distinct cellular contexts of compact embryos and gangly adults simply result in familiar signaling pathways and their diffusible triggers having different biological outcomes at different times—e.g., morphogenesis versus immune defense for TLRs. For insect, plant, and human Toll-related systems (14, 15), these signals course through a regulatory TH domain that intriguingly resembles a bacterial transducing engine (46).

Acknowledgments

We thank T. McClanahan, Dan Gorman, and their groups for support; D. Liggett for DNA synthesis; K. Anderson for the gift of a Drosophila Toll clone; N. Murgolo for threader help; D. Lundell for his experimental lead; and G. Zurawski, R. Debets, and T. Sana for critical comments. DNAX is supported by Schering–Plough.

ABBREVIATIONS

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- IL-1

interleukin 1

- IL-1R

IL-1 receptor

- TH

Toll homology

- LRR

leucine-rich repeat

- EST

expressed sequence tag

- STS

sequence-tagged site

- FISH

fluorescence in situ hybridization

- 18w

18 Wheeler

Note

After this manuscript was submitted, the cloning of a human Toll homolog identical to our TLR4 sequence was reported (55). As suspected, this molecule activates NF-κB and triggers the production of several inflammatory cytokines, hallmarks of an innate immune response.

Footnotes

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. U88540 and U88878–81 for human TLRs 1–5).

This work was presented earlier at the May 1997 Cold Spring Harbor Symposium on “Pattern Formation During Development” [Bazan, J. F., et al. (1997) in Symposium LXII, ed. Stillman, B. (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY), p. 23 (abstr).]

References

- 1.DeRobertis E M, Sasai Y. Nature (London) 1996;380:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arendt D, Nübler-Jung K. Mech Dev. 1997;61:7–21. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(96)00620-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miklos G L G, Rubin G M. Cell. 1996;86:521–529. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chothia, C. (1994) Development Suppl. 27–33. [PubMed]

- 5.Banfi S, Borsani G, Rossi E, Bernard L, Guffanti A, Rubboli F, Marchitiello A, Giglio S, Coluccia E, Zollo M, Zuffardi O, Ballabio A. Nat Genet. 1996;13:167–174. doi: 10.1038/ng0696-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.St. Johnston D, Nüsslein-Volhard C. Cell. 1992;68:201–219. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90466-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morisato D, Anderson K V. Annu Rev Genet. 1995;29:371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.29.120195.002103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belvin M P, Anderson K V. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:393–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemaitre B, Nicolas E, Michaut L, Reichhart J M, Hoffmann J A. Cell. 1996;86:973–983. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wasserman S A. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:767–771. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.8.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiang C, Beachy P A. Mech Dev. 1994;47:225–239. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Macke J P, Abella B S, Andreasson K, Worley P, Gilbert D J, Copeland N G, Jenkins N A, Nathans J. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4468–4476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitcham J L, Parnet P, Bonnert T P, Garka K E, Gerhart M J, Slack J L, Gayle M A, Dower S K, Sims J E. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5777–5783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardiman G, Rock F L, Balasubramanian S, Kastelein R A, Bazan J F. Oncogene. 1996;13:2467–2475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson I, Vogel J, Somerville S. Curr Biol. 1997;7:175–178. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(97)70082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altschul S F, Boguski M S, Gish W, Wootton J C. Nat Genet. 1994;6:119–129. doi: 10.1038/ng0294-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bork P, Gibson T J. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:162–184. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Attwood T K, Beck M E, Bleasby A J, Degtyarenko K, Michie A D, Parry-Smith D J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:212–217. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.1.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rost B, Sander C. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1996;25:113–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.25.060196.000553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King R D, Sternberg M J E. Protein Sci. 1996;5:2298–2310. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischer D, Rice D, Bowie J U, Eisenberg D. FASEB J. 1996;10:126–136. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.1.8566533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones D T. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:377–387. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nomura N, Miyajima N, Sazuka T, Tanaka A, Kawarabayasi Y, Sato S, Nagase T, Seki N, Ishikawa K, Tabata S. DNA Res. 1994;1:27–35. doi: 10.1093/dnares/1.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitamura T, Tojo A, Kuwaki T, Chiba S, Miyazono K, Urabe A, Takaku F. Blood. 1989;73:375–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lennon G, Auffray C, Polymeropoulos M, Soares M B. Genomics. 1996;33:151–152. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heng H H, Tsui L C. Methods Mol Biol. 1994;33:109–122. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-280-9:109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eldon E, Kooyer S, D’Evelyn D, Duman M, Lawinger P, Botas J, Bellen H. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1994;120:885–899. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buchanan S G S, Gay N J. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1996;65:1–44. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(96)00003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kajava A V, Vassart G, Wodak S J. Structure. 1995;3:867–877. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Casanova J, Furriols M, McCormick C A, Struhl G. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2539–2544. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.20.2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russell R B. Protein Eng. 1994;7:1407–1410. doi: 10.1093/protein/7.12.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heguy A, Baldari C T, Macchia G, Telford J L, Melli M. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2605–2609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Croston G E, Cao Z, Goeddel D V. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16514–16517. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schneider D S, Hudson K L, Lin T Y, Anderson K V. Genes Dev. 1991;5:797–807. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Norris J L, Manley J L. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1654–1667. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.9.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norris J L, Manley J L. Genes Dev. 1995;9:358–369. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Norris J L, Manley J L. Genes Dev. 1996;10:862–872. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.7.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taguchi T, Mitcham J L, Dower S K, Sims J E, Testa J. Genomics. 1996;32:486–488. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao Z, Henzel W J, Gao X. Science. 1996;271:1128–1131. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5252.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heldin C H. Cell. 1995;80:213–223. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galindo R L, Edwards D N, Gillespie S K, Wasserman S A. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1995;121:2209–2218. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.7.2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winans K A, Hashimoto C. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:587–596. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.5.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Groβhans J, Bergmann A, Haffter P, Nüsslein-Volhard C. Nature (London) 1994;372:563–566. doi: 10.1038/372563a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Volz K. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11741–11753. doi: 10.1021/bi00095a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parkinson J S. Cell. 1993;73:857–871. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90267-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ledvina P S, Yao N, Choudhary A, Quiocho F A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6786–6791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hultmark D. Trends Genet. 1993;9:178–183. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90165-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reichhart J M, Georgel P, Meister M, Lemaitre B, Kappler C, Hoffmann J A. C R Acad Sci (Paris) 1993;316:1218–1224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ip Y T, Reach M, Engstrom Y, Kadalayil L, Cai H, Gonzalez-Crespo S, Tatei K, Levine M. Cell. 1993;75:753–763. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90495-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dushay M S, Asling B, Hultmark D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10343–10347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosetto M, Engstrom Y, Baldari C T, Telford J L, Hultmark D. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;209:111–116. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Medzhitov R, Janeway C A., Jr Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:4–9. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80152-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lemaire P, Kodjabachian L. Trends Genet. 1996;12:525–531. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)81401-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Medzhitov R, Preston-Hurlburt P, Janeway C A. Nature (London) 1997;388:394–397. doi: 10.1038/41131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]