Abstract

Hormesis has emerged as an important manipulation for the study of aging. Although hormesis is manifested in manifold combinations of stress and model organism, the mechanism of hormesis are only partly understood. The increased stress resistance and extended survival caused by hormesis can be manipulated to further our understanding of the roles of intrinsic and induced stress resistance aging. Genes of the dauer/insulin/insulin-like signaling (IIS) pathway have well-established roles in aging in C. elegans. Here we discuss the role of some of those genes in the induced stress resistance and induced life extension attributable to hormesis. Mutations in three genes (daf-16, daf-18, and daf-12) block hormetically-induced life extension. However, of these three, only daf-18 appears to be required for a full induction of thermotolerance induced by hormesis, illustrating possible separation of the genetic requirements for stress resistance and life extension. Mutations in three other genes of this pathway (daf-3, daf-5 and age-1) do not block induced life extension or induced thermotolerance; daf-5 mutants may be unusually sensitive to hormetic conditions.

1. Introduction

The number of widely-accepted environmental interventions that slow aging is limited. Such interventions can be broadly categorized as caloric restriction, pharmacological interventions and hormetic treatments. When these interventions are completely understood, some overlap of mechanisms will likely be found. Caloric restriction is the most widely studied mechanism of life extension and has been studied extensively in numerous model organisms, especially rodents, but also Caenorhabditis elegans (Houthoofd et al., 2003; Klass, 1977; Lakowski and Hekimi, 1998). Another environmental intervention - drug treatments - has also been used to prolong survival in nematodes (Evason et al, 2005; Melov et al, 2000). A third type of intervention – hormesis – has become recognized more recently as a reliable mechanism for extending lifespan, and C. elegans is also a reliable model for further investigation of the mechanisms underlying this intervention, (Cypser and Johnson 2002, 2003; Lithgow et al., 1994; 1995).

Hormesis was reported as early as 1887 (for review, see Calabrese et al., 1999a). The term “hormesis was first coined by Southam and Ehrlich (1943), and can be defined as “stimulatory effects of low doses of substances known to be toxic at higher doses”. Hormesis typically stimulates the response 20–60% over the controls. These effects are typically found in response to doses of 20–25% of the minimum toxic dose, and the stimulatory dosages generally have a 10-fold range (Calabrese and Baldwin 1999b). It should be understood that hormesis is not a result of the culling of weak individuals from a population subjected to stress, followed by increased survival of those individuals who survived the stress because of intrinsic greater robustness. Experiments using large populations have demonstrated both increased stress resistance (Khazaeli et al., 1997) and increased life expectancy (Khazaeli et al., 1997; Michalski et al., 2001) without significant mortality

Resistance to the seemingly paradoxical effects of hormesis necessitated the extended and exhaustive documentation of the phenomenon, an effort led primarily by Edward Calabrese (Kaiser, 2003). Those efforts produced both practical and theoretical benefits. The practical benefit was an additional set of tools useful in studying survival, following the application of mild stress. The theoretical aspect was further support for the inverse correlation observed between stress resistance generally and improved survival. This review will focus on the effects of hormesis upon subsequent stress resistance and life span and also explore how the IIS pathway, known to modulate aging in the worm, also modulates hormesis.

2. The breadth and reality of hormesis

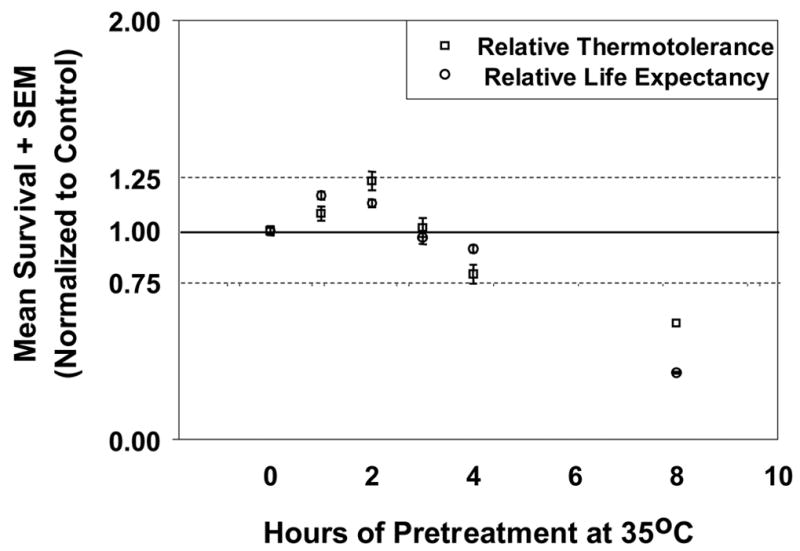

Hormetic effects have been documented in diverse combinations of stressors and recipient organism. Such sub-lethal stress pretreatments have been shown to increase germination growth in plants, cell proliferation in culture, protein turnover, subsequent stress resistance, and life expectancy. Stressors reported to increase subsequent stress resistance include heat, cold, hypergravity and pesticides. Increased life span has been reported after a similarly diverse number of hormetic treatments including heat, cold, hypergravity, ionizing radiation; exercise, electric shock, and wounding accompanied by regrowth (Martinez, 1996; Minois, 2000). Some of the earliest work in C. elegans by Lithgow et al (1994; 1995) demonstrated hormesis in response to sub-lethal heat treatment, affecting both subsequent heat resistance as well as longevity. We have expanded on that work to demonstrate the close relationship between the amount of exposure to a toxin and the level of induced stress resistance or induced life extension in C. elegans (Cypser and Johnson, 2002; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hormetic heat treatments induce both increased thermotolerance and improved survival. The similarity of the two dose-response curves is consistent with a relationship between stress resistance and aging. (Modified from Cypser and Johnson, 2002).

2.1. The basis of hormesis

The biological mechanisms underlying hormesis are far from clear. The hormetic response may require transcription, translation, and/or post-translational protein modification, such as phosphorylation. Calabrese and Baldwin (2002) have suggested that hormesis is best defined by a description of dose and response, and that “…no single hormetic mechanism is expected, but a common evolutionary-based homeostasis maintenance regulatory strategy is evident.”

The same authors point out that a given hormetic response may reflect one of two forms, either a direct stimulation or an overcompensation response. Minois (2000) has proposed an alternative description wherein hormesis is seen as a consequence of metabolic regulation coupled to the expression of stress response proteins. These two views are not mutually exclusive; however a full discussion of the molecular nature of hormesis is beyond the scope of this review.

2.2. Dietary restriction as hormesis

The best-documented and most powerful non-genetic intervention known to extend life span, in a broad variety of species, is caloric restriction (McCay 1935; Weindruch and Walford 1988; Yu 1994; for review, see Weindruch 1996). Johnson et al. (1996) and Masoro (1998, 2000) have suggested that caloric restriction may be a form of hormesis. Animals restricted to a balanced diet, containing as little as 60% of the calories they would consume ad libitum, have life expectancies up to 50% greater than ad libitum controls. This argument requires that caloric restriction be considered a stressor, and in fact caloric restriction does promote the expression of stress response factors, including corticosterone, glucocorticoids (Masoro 1995) and heat shock proteins (Aly et al., 1994; Heydari et al., 1996; Moore et al., 1998). Caloric restriction can be induced in the worm in multiple ways. Klass (1977) demonstrated caloric restriction in response to reduced food concentration. The Eat mutations in C. elegans produce physiological defects which slow feeding, and also display increased lifespan (Lakowski and Hekimi 1998) and thermotolerance (Johnson et al., 2001). Houthoofd et al. (2003) have shown that axenic medium can extend life span about three-fold independently of daf-16. Indeed when this form of caloric restriction is used to treat a daf-2 mutant, an eight-fold extension in life can be achieved (Houthoofd et al., 2004).

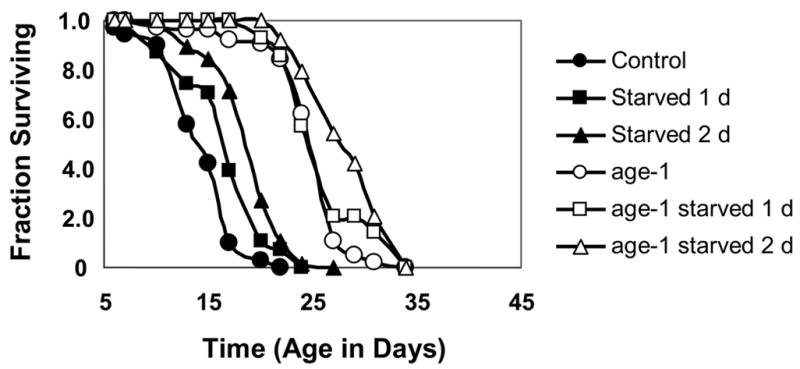

Complete caloric deprivation – that is, starvation - can also serve as a hormetic treatment to extend life span of C. elegans. Young adult worms deprived of all food for 1 – 3 days display an increase in mean life span of 30 – 40%. Interestingly, the relative size of this effect appears to be reduced in animals carrying a mutation in age-1. It may be that the age-1 mutants have nearly maximized the effect, rendering sizable further increases in life span unattainable by the same mechanism (Figure 2). Additionally, a mutation in daf-16 appears to reduce this effect (Tedesco and Johnson, unpublished).

Figure 2.

Short-term starvation extends lifespan in C. elegans. age-1 mutants display a relatively smaller effect size. Animals in experimental groups were transferred to liquid medium (S Basal) containing no food for 1 day or two days, then returned to survival medium (Johnson and Wood, 1982) for the duration of survival. Mean ± SEM (days) and p-value (log-rank) compared to unstarved control: For N2 (unstarved), 14.8 ± 0.3, NA; N2 (starved 1 day), 16.9 ± 0.4, p < 0.001; N2 (starved 2 days): 19.3 ± 0.3, p < 0.0001. For age-1 (unstarved), 25.3 ± 0.4, NA; age-1 (starved 1 day), 26.5 ± 0.4, p not significant; age-1 (starved 2 days), 28.8 ± 0.4, p < 0.0001.

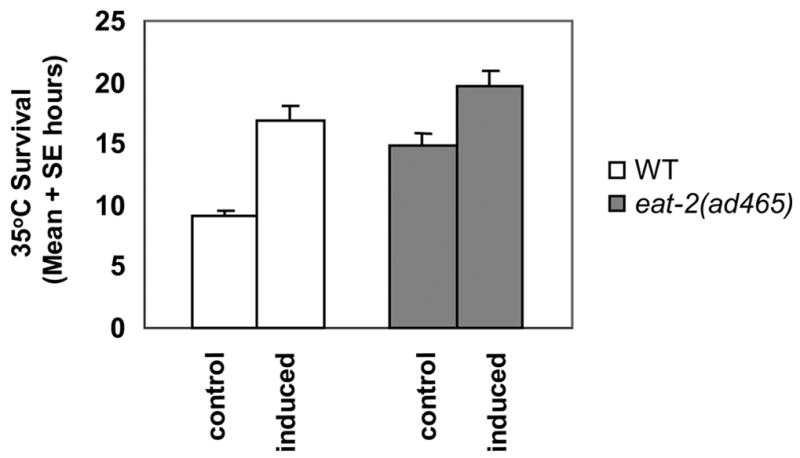

However, Neafsey (1990) has concluded that mortality analysis of caloric restriction and other forms of hormesis indicate that they are different entities. In addition, the nematode Eat mutant which displays the greatest increase in life span [eat-2(ad465)] can have its intrinsic resistance to heat increased even further by a hormetic heat pretreatment (Figure 3). Although it is not clear that the effects of both caloric restriction and heat pre-treatment have been maximized, these results are consistent with the two effects being qualitatively different. Whether these (presumably) additive effects for thermotolerance translate into increased life expectancy has not been tested. Taken together, these results indicate that caloric restriction may be a hormetic phenomenon in the broad sense, but the contributions of caloric restriction and other sub-lethal stress pretreatments may contribute independently to increased stress resistance and life expectancy.

Figure 3.

Relative benefits derived from hormesis. Mean ± SEM (hours) and p-value by t-test from comparison of naïve and heat-pretreated animals (for N2): naive, 9.1 ± 0.4; pretreated, 16.9 ± 1.1, p < 0.0001, (for eat-2[ad465]): naive, 14.8 ± 0.8, pretreated, 19.8 ± 1.1, p < 0.001.

3. The correlation between stress resistance and longevity

There is a strong correlation between increased stress resistance and life span extension among various mutants representing diverse species, including yeast, the nematode, the fly and the mouse (Finkel and Holbrook 2000). Numerous examples of the correlation between increased stress resistance and life span extension are known from C. elegans (Johnson et al., 2001). Furthermore, this correlation has been found in strains derived by selective breeding, in animals carrying single-gene mutations (Johnson et al, 2001), in transgenic animals, and in response to environmental interventions. However, while stress resistance appears to be necessary for life span extension, it is not sufficient; C. elegans carrying the daf-4 or daf-7 mutations are thermotolerant but not long-lived (Lithgow et al. 1995).

4. Genetics of induced thermotolerance in C. elegans

The IIS pathway mediates both life span and intrinsic stress resistance in C. elegans. Mutations in age-1 or daf-2 increase both life expectancy (Friedman and Johnson 1988a, b; Kenyon et al., 1993) and stress resistance (Barsyte et al., 2001; Larsen 1993; Lithgow et al., 1994, 1995; Murakami and Johnson, 1996; Vanfleteren 1993), and mutations in daf-16 or daf-18 suppress both the increased life span (Dorman et al., 1995; Kenyon et al., 1993; Larsen et al., 1995; Mihaylova et al., 1999) and the increased stress resistance (Barsyte et al., 2001; Murakami and Johnson 1996;). Wild-type animals display greater life span (Butov et al., 2001; Lithgow et al., 1995; Michalski et al., 2001; Yashin et al., 2001; 2002) and thermotolerance (Cypser and Johnson, 2002) in response to pretreatment with sub-lethal heat stress.

Given the well-established correlation between stress resistance and longevity and the importance of the IIS response pathway to intrinsic longevity, we wondered whether the same pathway might also modulate hormetic responses. We asked whether this pathway was required for heat-induced stress resistance, and heat-induced life extension attributable to hormesis.

4.1. Genetics of induced thermotolerance in C. elegans

We have found that several mutants of the IIS pathway display increased thermotolerance in response to pretreatment with sub-lethal doses of heat. Several dauer-defective mutants that interfere with signaling (daf-3(e1376), daf-5(e1386), daf-12(m20), daf-16(m26), daf-16(m27) and daf-16(mgDf50)) were tested and these mutants all displayed induced thermotolerance similar to that of the wild-type (daf-5 mutants displayed a significantly greater induced thermotolerance than did wild-type controls). In contrast, we found that although daf-18(e1375) and daf-18(nr2037) mutants do significantly increase their thermotolerance, the induced thermotolerance is still significantly less than that displayed by pretreated wild-type animals (Cypser 2002).

4.2. Genetics of induced life extension in C. elegans

We tested the effects of mutations in daf-3, daf-5, daf-12, daf-16, daf-18, and age-1 on hormetic life extension caused by sub-lethal heat treatment. We found that three Daf-d mutants, daf-12(m20), daf-16(m27), and daf-18(nr2037), lack the ability to increase their life expectancy in response to this pretreatment (Cypser and Johnson, 2003). daf-5 and age-1 mutants (and daf-3 mutants, although the evidence is not so robust) show induced life extension. age-1 mutants overall display a significant increase in life span after heat pretreatment beyond that conferred by the age-1 mutation. The daf-5 mutant we tested was significantly shorter-lived than wild-type controls; however, it is striking that pretreatment with the conditions known to extend the life span of the wild type compensated for this defect.

5. Discussion

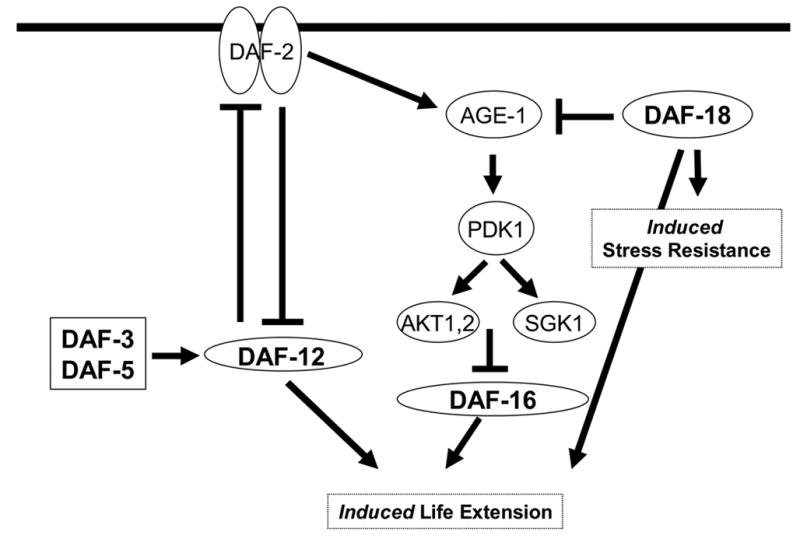

We conclude that genes of the IIS pathway are required for hormetic effects in C. elegans (Figure 4). daf-18 is required for both hormetic life extension as well as hormetic thermotolerance. In spite of having no effect on induced thermotolerance, the daf-12 and daf-16 genes appear to be required for the hormetic life extension seen in response to the same conditions of heat pretreatment that induces thermotolerance. (In an interesting contrast, Fisher and Lithgow (2006) have demonstrated an allele-specific role for daf-12 in intrinsic thermotolerance) Thus some separation of the genetic requirements for stress resistance and life extension is evident.

Figure 4.

Genes of the insulin/IGF-2 signaling pathway are required for induced stress resistance and induced life extension. daf-18 appears to be required for heat-induced thermotolerance independently of daf-16. However, the daf-12, daf-16 and daf-18 mutants tested were all found to be defective for life extension induced by heat pretreatment. (Modified from Cypser and Johnson, 2003).

The relationship between stress resistance and life expectancy provides an important frame of context for the study of aging, and hormesis provides an important tool to disentangle improved survival from secondary phenotypes. The worm is an excellent model of induced stress resistance and induced life extension, because hormesis has been well-characterized in C. elegans. Indeed, Rea et al (2005) have shown that level of expression of hsp-16 predicts both thermotolerance and survival of individual worms subsequent to hormetic conditions. Further investigations of hormetic phenotypes at the molecular and physiological level should contribute to our understanding of aging and the life-history tradeoffs that affect aging.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aly KB, Pipkin JL, Hinson WG, Feuers R, Duffy P, Lyn-Cook L, Hart R. Chronic caloric restriction induces stress proteins in the hypothalamus of rats. Mech Ageing Dev. 1994;76:11–23. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsyte D, Lovejoy DA, Lithgow GJ. Longevity and heavy metal resistance in daf-2 and age-1 long-lived mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans. FASEB J. 2001;15:627–634. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-0966com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butov AA, Johnson TE, Cypser JR, Sannikov IA, Volkov MA, Sehl ME, Yashin AI. Hormesis and debilitation effects in stress experiments using the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans: The model of balance between cell damage and HSP levels. Exp Gerontol. 2001;37:57–66. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(01)00161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese EJ, Baldwin LA, Holland CD. Hormesis: A highly generalizable and reproducible phenomenon with important implications for risk assessment. Risk Anal. 1999;19:261–281. doi: 10.1023/a:1006977728215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese EJ, Baldwin LA. Reevaluation of the fundamental dose-response relationship - A new database suggests that the U-shaped, rather than the sigmoidal, curve predominates. Bioscience. 1999;49:725–732. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese EJ. Evidence that hormesis represents an "overcompensation" response to a disruption in homeostasis. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 1999;42:135–137. doi: 10.1006/eesa.1998.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese EJ, Baldwin LA. The marginalization of hormesis. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2000;19:32–40. doi: 10.1191/096032700678815594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese EJ, Baldwin LA. Defining hormesis. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2002;21:91–97. doi: 10.1191/0960327102ht217oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cypser JR. PhD Thesis. University of Colorado Press; 2002. Characterization and Genetics of Induced Stress Resistance and Life Extension in Caenorhabditis elegans; pp. 96–104. [Google Scholar]

- Cypser JR, Johnson TE. The spe-10 mutant has longer life and increased stress resistance. Neurobiol Aging. 1999;20:503–512. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(99)00085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cypser JR, Johnson TE. Multiple stressors in Caenorhabditis elegans induce stress hormesis and extended longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57A:B109–B114. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.3.b109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cypser JR, Johnson TE. Hormesis in Caenorhabditis elegans dauer-defective mutants. Biogerontology. 2003;4:203 – 214. doi: 10.1023/a:1025138800672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman JB, Albinder B, Shroyer T, Kenyon C. The age-1 and daf-2 genes function in a common pathway to control the life-span of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1995;141:1399–1406. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.4.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evason K, Huang C, Yamben I, Covey DF, Kornfeld K. Anticonvulsant medications extend worm life-span. Science. 2005;307:258 – 262. doi: 10.1126/science.1105299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408:239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher AL, Lithgow GJ. The nuclear hormone receptor DAF-12 has opposing effects on Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan and regulates genes repressed in multiple long-lived worms. Aging Cell. 2006;5:127–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman DB, Johnson TE. A mutation in the age-1 gene in Caenorhabditis elegans lengthens life and reduces hermaphrodite fertility. Genetics. 1988a;118:75–86. doi: 10.1093/genetics/118.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman DB, Johnson TE. Three mutants that extend both mean and maximum life span of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans, define the age-1 gene. J Gerontol. 1988b;43:B102–B109. doi: 10.1093/geronj/43.4.b102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furst A. Hormetic effects in pharmacology: pharmacological inversions as prototypes for hormesis. Health Phys. 1987;52:527–530. doi: 10.1097/00004032-198705000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heydari AR, You S, Takahashi R, Gutsmann A, Sarge KD, Richardson A. Effect of caloric restriction on the expression of heat shock protein 70 and the activation of heat shock transcription factor 1. Dev Genet. 1996;18:114–124. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1996)18:2<114::AID-DVG4>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houthoofd K. Life extension via dietary restriction is independent of the Ins/IGF-1 signalling pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. Exp Gerontol. 2003;38:947–954. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(03)00161-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houthoofd K, Braeckman BP, Vanfleteren JR. No abstract The hunt for the record life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Journal of Gerontology A: BIOLOGICAL AND MEDICAL SCIENCES. 2004;59:408–410. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.5.b408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TE, de Castro E, de Castro SH, Cypser JR, Henderson S, Tedesco PM. Relationship between increased longevity and stress resistance as assessed through gerontogene mutations in Caenorhabditis elegans. Exp Gerontol. 2001a;36:1609–1617. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(01)00144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TE, Wood WB. Genetic analysis of life-span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:6603–6607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.21.6603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon C, Chang J, Gensch E, Rudner A, Tabtiang R. A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature. 1993;366:461–464. doi: 10.1038/366461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khazaeli AA, Tatar M, Pletcher SD, Curtsinger JW. Heat-induced longevity extension in Drosophila. I Heat treatment, mortality, and thermotolerance. J Gerontol. 1997;52A:B48–B52. doi: 10.1093/gerona/52a.1.b48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klass MR. Aging in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: major biological and environmental factors influencing life span. Mech Ageing Dev. 1977;6:413–429. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(77)90043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakowski B, Hekimi S. The genetics of caloric restriction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13091–13096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb MJ, McDonald RP. Heat tolerance changes with age in normal and irradiated Drosophila melanogaster. Exp Gerontol. 1973;8:207–217. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(73)90028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen P. Aging and resistance to oxidative damage in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8905–8909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen P, Albert PS, Riddle DL. Genes that regulate both development and longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1995;139:1567–1583. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.4.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bourg E, Minois N. Increased longevity and resistance to heat shock in Drosophila melanogaster flies exposed to hypergravity. C R Acad Sci III. 1997;320:215–221. doi: 10.1016/s0764-4469(97)86929-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lithgow GJ, White TM, Hinerfeld DA, Johnson TE. Thermotolerance of a long-lived mutant of Caenorhabditis elegans. J Gerontol. 1994;49:B270–B276. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.6.b270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lithgow GJ, White TM, Melov S, Johnson TE. Thermotolerance and extended life-span conferred by single-gene mutations and induced by thermal stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7540–7544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund J, Tedesco PM, Duke K, Wang J, Kim SK, Johnson TE. Transcriptional profile of aging in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1566–1573. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez DE. Rejuvenation of the disposable soma: repeated injury extends lifespan in an asexual annelid. Exp Gerontol. 1996;31:699–704. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(96)00099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masoro EJ. Dietary restriction. Exp Gerontol. 1995;30:291–298. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(94)00028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masoro EJ. Hormesis and the antiaging action of dietary restriction. Exp Gerontol. 1998;33:61–66. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(97)00071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masoro EJ. Hormesis is the beneficial action resulting from the response of an organism to a low-intensity stressor. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2000;19:340–341. doi: 10.1191/096032700678816034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCay C, Crowell M, Maynard L. The effect of retarded growth on the length of life and upon ultimate size. J Nutr. 1935;10:63–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melov S, Ravenscroft J, Malik S, et al. Extension of life-span with superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics. Science. 2000;289:1567–1569. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalski AI, Johnson TE, Cypser JR, Yashin AI. Heating stress patterns in Caenorhabditis elegans longevity and survivorship. Biogerontology. 2001;2:35–44. doi: 10.1023/a:1010091315368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihaylova VT, Borland CZ, Manjarrez L, Stern MJ, Sun H. The PTEN tumor suppressor homolog in Caenorhabditis elegans regulates longevity and dauer formation in an insulin receptor-like signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7427–7432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minois N. Longevity and aging: beneficial effects of exposure to mild stress. Biogerontology. 2000;1:15–29. doi: 10.1023/a:1010085823990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SA, Lopez A, Richardson A, Pahlavani MA. Effect of age and dietary restriction on expression of heat shock protein 70 in rat alveolar macrophages. Mech Ageing Dev. 1998;104:59–73. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(98)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami S, Johnson TE. A genetic pathway conferring life extension and resistance to UV stress in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1996;143:1207–1218. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.3.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neafsey PA. Longevity hormesis: A review. Mech Ageing Dev. 1990;51:1–31. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(90)90158-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedzwiecki A, Kongpachith AM, Fleming JE. Aging affects expression of 70-kDa heat shock proteins in Drosophila. J Biol Chem. 1991:9332–9338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rea SL, Wu D, Cypser JR, Vaupel JW, Johnson TE. A stress-sensitive reporter predicts longevity in isogenic populations of C. elegans. Nat Genet. 2005;37:894 – 898. doi: 10.1038/ng1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southam CM, Ehrlich J. Effects of extract of western red-cedar heartwood on certain wood-decaying fungi in culture. Phytopathology. 1943;33:517–524. [Google Scholar]

- Stebbing AR. Growth hormesis - a by-product of control. Health Phys. 1987;52:543–547. doi: 10.1097/00004032-198705000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Voorhies W. Production of sperm reduces nematode life span. Nature. 1992;360:456–458. doi: 10.1038/360456a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanfleteren JR. Oxidative stress and ageing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem J. 1993;292:605–608. doi: 10.1042/bj2920605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weindruch R, Walford RL. The Retardation of Aging and Disease by Dietary Restriction. Charles C. Thomas; Springfield, IL: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Weindruch R. Caloric restriction and aging. Sci Am. 1996;274:46–52. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0196-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis P, Weis JS. Cadmium acclimation and hormesis in Fundulus heteroclitis during regeneration. Environ Res. 1986;39:356–363. doi: 10.1016/s0013-9351(86)80061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yashin AI, Cypser JR, Johnson TE, Michalski AI, Boyko SI, Novoseltsev VN. Ageing and survival after different doses of heat shock: the results of analysis of data from stress experiments with the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;122:1477–1495. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00273-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yashin AI, Cypser JR, Johnson TE, Michalski AI, Boyko SI, Novoseltsev VN. Heat shock changes the heterogeneity distribution in populations of Caenorhabditis elegans: does it tell us anything about the biological mechanism of stress response? J Gerontol. 2002;57A:B83–B92. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.3.b83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu BP. Modulation of Aging Processes by Dietary Restriction. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1994. [Google Scholar]