Abstract

Many current theories of Parkinson's disease (PD) suggest that oxidative stress is involved in the neurodegenerative process. Potential neuroprotective agents could protect neurons through inherent antioxidant properties or through the upregulation of the brain's antioxidant defenses. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) has been shown to protect and restore dopamine neurons in experimental models of PD and to improve motor function in human patients. This study was designed to investigate GDNF's effect on oxidative stress in a model of PD. GDNF or vehicle was injected into the right striatum of male Fischer-344 rats. Three days later 6-OHDA or saline was injected into the same striatum. The striatum and substantia nigra from both sides of the brain were removed 24 hours after 6-OHDA or saline injection and analyzed for the oxidative stress markers protein carbonyls and 4-hydroxynonenal. Both markers were significantly reduced in GDNF + 6-OHDA treated animals compared to vehicle + 6-OHDA treated animals. In addition, in animals allowed to recover for 3.5 to 4 weeks after the 6-OHDA administration, the GDNF led to significant protection against loss of striatal and nigral tissue levels of dopamine. These results suggest that the protective effects of GDNF against 6-OHDA involve a reduction in oxidative stress.

Keywords: GDNF, reactive oxygen species, protein carbonyls, 4-hydroxynonenal, striatum, substantia nigra, dopamine

Oxidative stress is a common characteristic of many of the current theories of the etiology of Parkinson's disease (PD). It is implicated either as a cause or result of the neurodegeneration associated with PD [4, 29, 36, 38] and is also considered an important component in neurodegeneration in other models and diseases such as traumatic brain injury [3], HIV-related dementia [1], cerebral ischemia [5], Alzheimer's disease [32], and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [34].

Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) has been shown to have both protective and restorative properties in vivo, particularly regarding the dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra [12, 16, 22]. In addition to its effects in models of PD, GDNF has demonstrated similar protective and restorative effects in other models of neurodegeneration [6, 17, 26, 48]. Although the protective and restorative properties of GDNF have been well documented, the mechanisms behind these properties are still relatively unknown.

Increases in oxidative stress can be detected before signs of neuronal degeneration [15, 47], suggesting that oxidative stress may be an early component of neuronal loss. This study was designed to investigate GDNF's ability to reduce the generation of oxidative stress in a rodent model of PD. To carry out these studies, young adult rats received GDNF prior to 6-OHDA. Dopamine (DA) was measured in the striatum and substantia nigra to confirm GDNF's ability to reduce 6-OHDA-induced depletion of DA. Protein carbonyls and 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) were assayed to measure GDNF's ability to reduce or inhibit oxidative stress. The measurement of protein carbonyls is one of the most widely accepted techniques to measure oxidative damage [41], and HNE is the most abundant cytotoxic molecule generated in vivo under oxidative conditions [45].

Young adult (12-21 weeks, 230g-326g) male Fischer-344 rats (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Indianapolis, IN) were used for all experiments. Animals were housed in groups of two under a 12-hour light/dark cycle with food and water freely available. All animal use procedures were in strict accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Kentucky.

The rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (2.0-2.5% as needed) and placed into a stereotaxic frame. The skull was exposed and a small burr hole was drilled in the skull above the right striatum (0.0 mm posterior to bregma, 3.4 mm right of midline). The site of GDNF administration was selected to be located between the two subsequent 6-OHDA injection sites. The dura was cut and a SGE syringe with a 26 gauge blunt-tipped needle was slowly lowered to a depth of 5.0 mm below the surface of the brain. 5 μl of either vehicle (10 mM citrate buffer with 150 mM NaCl, pH 5.0) or 5 μg of GDNF (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) dissolved in vehicle was injected at a rate of 0.5 μl/minute for 10 minutes into the striatum. The needle was left in place for an additional 5 minutes following the injection and then slowly withdrawn. The burr hole was filled with Gelfoam and the incision closed with wound clips. Three days after the first surgery, the rats were again anesthetized with isoflurane and placed into a stereotaxic frame. 6-OHDA sites of administration were based upon previous work in our lab [40] and adapted from Kirik et al. [24]. The skull was exposed and 2 small burr holes were drilled in the skull above the right striatum (0.5 mm posterior to bregma, 4.2 mm right of midline; 0.5 mm anterior to bregma, 2.5 mm right of midline). The dura was cut and a SGE syringe with a 26 gauge blunt-tipped needle was slowly lowered to a depth of 5.0 mm below the surface of the brain. 2 μl of either vehicle (0.9% saline with 0.1% ascorbic acid, pH 5.5) or 10 μg of 6-OHDA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in vehicle was injected at a rate of 0.4 μl/minute for 5 minutes into each of the two sites. The needle was left in place for an additional 5 minutes following each injection and then slowly withdrawn. The burr holes were filled with Gelfoam and the incision closed with wound clips.

Striatal and nigral tissue was collected for the measurement of oxidative stress markers 24 hours after the 6-OHDA or saline injections. Tissue was collected for the measurement of DA levels from a separate group of animals 3½ to 4 weeks after 6-OHDA or saline injections. All animals were rendered unconscious with CO2, decapitated and the brains quickly removed and chilled in ice-cold saline. A coronal slice 2 mm thick was removed at the level of the striatum using a chilled brain mold (Rodent Brain Matrix; ASI Instruments, Warren, MI). The left and right striata were then dissected from the slice. A similar 2 mm coronal slice was made through the midbrain and the substantia nigra removed from both sides of the brain. All tissue samples were placed in pre-weighed vials, weighed and frozen on dry ice. The samples were stored at −80°C until analysis.

Tissue levels of DA were analyzed using high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) with electrochemical detection as described previously [7]. The retention times of standards were used to identify peaks, and peak heights were used to determine amount of recovery of internal standard (dihydroxybenzylamine) and amounts of DA.

The primary focus of these studies was on the effects of GDNF on nigrostriatal DA neurons. Thus, for the measurement of oxidative stress markers in the striatum we prepared crude synaptosomes in order to remove some of the non-dopaminergic elements (neuronal and glial cell bodies). Striatal tissue was homogenized with a Teflon pestle in cold 0.32 M sucrose buffer containing protease inhibitors (Complete, Mini; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and centrifuged for 15 minutes at 1000 × g. The supernatant was transferred to a clean vial and centrifuged a second time for 15 minutes at 12,500 × g. The supernatant was discarded and the resulting crude synaptosomes were resuspended in 50 μL of buffer. For the substantia nigra, as we were interested in dopaminergic cell bodies, we used whole tissue rather than synaptosomes to ensure inclusion of the cell bodies. Nigral tissue was homogenized with a sonicator in cold 0.32 M sucrose buffer containing protease inhibitors. Protein concentrations were determined using the Pierce BCA method (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL).

The methods for determining protein carbonyls and HNE by slot blots have been described previously as rapid and effective methods of measuring markers of oxidative stress [35, 42]. For protein carbonyls, equal volumes of protein (15 μg), 12% SDS, and the derivatizing agent 2,4-dinitriphenylhdrazine (DNP) (OxyBlot Protein Oxidation Detection Kit; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) were incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes and the reaction was stopped with a neutralizing solution. 250 ng of derivatized proteins were slot-blotted to a nitrocellulose membrane via vacuum filtration through a 48 well template (Bio-Dot SF; BioRad, Hercules, CA). For HNE analysis, 15 μg of protein per sample was slot-blotted onto the membrane by the same method. The membrane was blocked with 3% BSA for 1 hour, followed by incubations with rabbit anti-DNP (1:150, Chemicon) for 1 hour for protein carbonyls or rabbit anti-HNE (1:10,000, Alpha Diagnostic, San Antonio, TX) for 2 hours for HNE. This was followed by goat anti-rabbit conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (1:15,000, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 1 hour, and an alkaline phosphatase substrate (SigmaFast; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). After drying, the developed membrane was scanned and the optical density of the samples quantified densitometrically using Scion Image.

Data from the slot blots were expressed as a ratio of the side ipsilateral to the injections to the side contralateral to the injections (I:C ratio). Tissue levels of DA were expressed as ng/g wet weight of tissue. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. All data were analyzed by ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls post hoc comparisons. P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

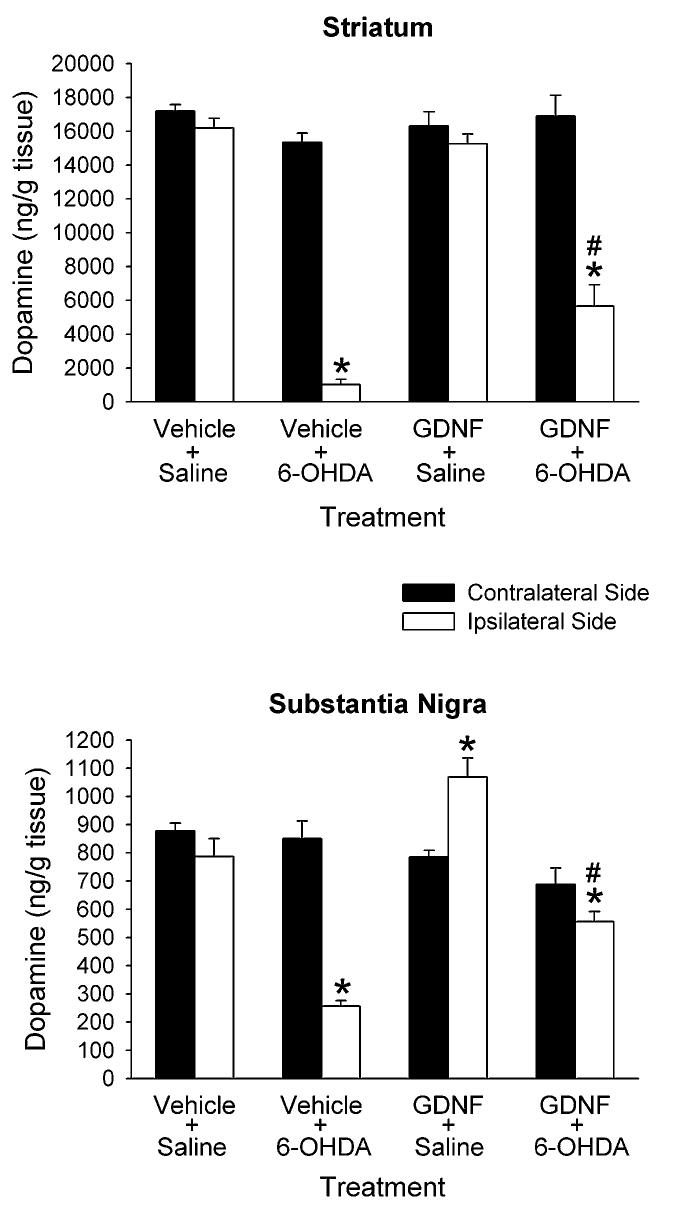

Figure 1 shows striatal and nigral tissue levels of DA measured 3.5 to 4 weeks after 6-OHDA or saline injection. In the animals that received vehicle + 6-OHDA, there was a significant decrease in DA of 93% in the ipsilateral striatum compared to the contralateral striatum, and a significant decrease in DA of 70% in the ipsilateral nigra compared to the contralateral nigra. The GDNF treatments significantly reduced the DA-depleting effects of the 6-OHDA. In the animals treated with GDNF + 6-OHDA, the decrease in striatal DA was 66% in the ipsilateral striatum compared to the contralateral striatum, and the decrease in nigral DA was 19% in the ipsilateral side compared to the contralateral side. In the GDNF + saline treated animals, the GDNF had no effect on striatal DA levels, but did increase nigral DA levels by 36%.

Figure 1.

Tissue levels of DA in rats treated with intrastriatal vehicle or GDNF 3 days before intrastriatal saline or 6-OHDA. DA was measured in the striatum and substantia nigra 3.5 to 4 weeks later. Results are means ± SEM from 6 - 8 animals per group. *p<0.05 vs. contralateral side of same group, # p<0.05 vs. ipsilateral side of vehicle + 6-OHDA group (two-way ANOVA with side as a within factor followed by Newman-Keuls post hoc comparisons).

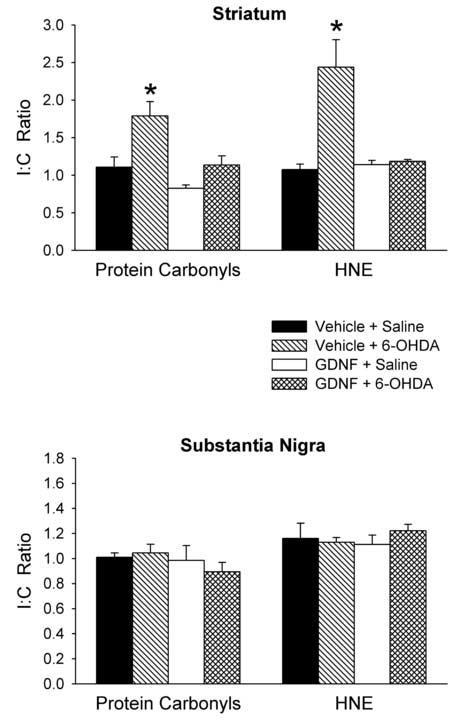

Protein carbonyls and HNE were measured 24 hours after intrastriatal administration of 6-OHDA or saline. This time period was chosen based on previous experiments where increases in striatal levels of protein carbonyls and HNE occurred 1 day, but not 3, 7 or 14 days after intrastriatal injections of 6-OHDA [40] . In animals treated with vehicle + 6-OHDA there was a significant increase in the I:C ratio for both protein carbonyls (+62%) and HNE (+127%) in the striatum (Fig. 2). Administration of GDNF 3 days prior to the 6-OHDA completely prevented the 6-OHDA-induced increases in protein carbonyls and HNE in the striatum. Neither the GDNF nor the 6-OHDA injections had any effect on the I:C ratios for protein carbonyls or HNE in the substantia nigra (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Effects of GDNF on protein carbonyl and HNE levels. GDNF or vehicle was injected into the right striatum 3 days before 6-OHDA or saline was injected into the same striatum. Tissue samples were collected 24 hours after the 6-OHDA or saline injections. Protein carbonyls and HNE content were measured in the striatum and substantia nigra and a ratio of the ipsilateral to contralateral side (I:C Ratio) was calculated for each animal for each region. Results are mean ± SEM for 6 animals per group. *p<0.05 vs. all other groups (one-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls post hoc comparisons).

The present results suggest that GDNF, when administered prior to 6-OHDA, decreases the amount of oxidative stress produced by 6-OHDA and reduces the loss of DA in the striatum and substantia nigra. These results concerning DA levels are analogous to previous findings that a single injection of GDNF into the striatum attenuates the loss of DA and neurons in the nigrostriatal pathway of rodents lesioned with 6-OHDA [2, 8, 25]. Our studies suggest that the observed reduction in oxidative stress markers is likely due to downstream effects of GDNF. Neuroprotective effects of GDNF are abolished when protein synthesis is inhibited [21], and following a single injection of GDNF into the striatum, GDNF is retrogradely transported to the substantia nigra and is present in the striatum only in very low levels 3 days after administration [43]. The 6-OHDA-induced loss of DA was attenuated in our study when GDNF was administered 3 days prior to 6-OHDA, which suggests that the protective effects we observed are likely due to downstream effects of GDNF. A similar finding in regards to GDNF's downstream effects was found in a primate model of PD in which GDNF was continuously infused into the brain for two months and then stopped [14]. The improved behavioral effects due to the GDNF were still observable for at least two months after the administration of GDNF was halted.

Previous studies in our lab have looked at the generation of oxidative stress following a striatal injection of 6-OHDA [40]. An increase in markers of oxidative stress in the striatum occurred 24 hours after 6-OHDA. This increase was absent at 3, 7, and 14 after 6-OHDA. We did not see an increase in oxidative stress markers at any of these time points in the substantia nigra. DA measurements taken at the same time points showed a significant decrease in the striatum at all time points, while DA in the substantia nigra was not decreased until day 7. It has been suggested that ROS initiate signal transduction pathways, such as that of apoptosis, which commence in neuronal terminals and terminate in the cell bodies [30, 31]. Thus, apoptotic events initiated in striatal DA terminals may be leading to retrograde degeneration or damage to DA cell bodies in the absence of observable oxidative stress in the substantia nigra.

We are unaware of any other studies that have demonstrated in an in vivo model that the increase in oxidative stress observed after striatal administration of 6-OHDA is attenuated by prior administration of GDNF. In vitro studies have shown that GDNF can reduce oxidative stress-induced cell death [13, 44, 46], and there is evidence that a single injection of GDNF causes an increase in the activity of superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase in vivo in non-lesioned rodents [9]. Oxidative stress is increased in patients with PD [18, 23, 37], and GDNF has been demonstrated to improve motor function in patients with PD [33, 39]. Thus, our findings that GDNF attenuates neurotoxin-induced oxidative damage in vivo may relate to the positive behavioral effects that have been reported in some patients, and adds to the understanding of the protective properties of GDNF. To more fully appreciate these properties it will be important to determine in future studies the effects that GDNF has on endogenous antioxidant systems in in vivo models of neurodegeneration.

The I:C ratios for the protein carbonyls and HNE in the GDNF + 6-OHDA treated animals were not statistically different than the non-lesioned controls. However, there was still a significant decrease in striatal DA levels in the GDNF + 6-OHDA animals when comparing these same groups. One possibility for this discrepancy is that neurons lesioned by 6-OHDA may be destroyed by more than one mechanism. Conflicting reports exists in reference to the mechanisms involved with 6-OHDA-induced cell death. Most research shows that 6-OHDA induces apoptosis [10, 28, 49]. However, there are reports of increased apoptotic factors without corresponding changes in cellular morphology [19, 20, 27]. In vitro studies have demonstrated that while GDNF enhances the viability of DA neurons against 6-OHDA, it does not completely inhibit cell death [11, 46]. Oxidative stress is likely not involved in all aspects of the degeneration associated with 6-OHDA, which could account for the results that we obtained. In addition, indicators of oxidative stress that were not quantified in the present study (such as levels of glutathione, hydrogen peroxide or nitric oxide) may be involved. Thus, further studies are needed to more fully define the protective effects of GDNF.

The results from the present study suggest that GDNF is involved in the attenuation of free radical damage, at least in terms of the 6-OHDA lesioned rodent model. Though the effects of GDNF are well documented, the mechanisms involved in how GDNF induces neuroprotection have not been completely elucidated. Uncovering these mechanisms may give insight into sources of neuronal loss in PD and other neurodegenerative disorders. GDNF's ability to attenuate oxidative stress is only one of its overall effects, and studying these protective effects advances understanding of how GDNF may prevent the further loss of neurons in PD. Because PD is a progressive disease, the prevention of further loss of neurons is a major factor in treatment. At present, GDNF must be administered directly into the brain. Thus, its use as a conventional therapeutic agent may be limited. However, the results that have been demonstrated in both models of PD and in humans have been substantial and promising; and therefore, continued study of GDNF may lead to the development of other compounds or therapeutic strategies that will be beneficial for the treatment of PD and other neurodegenerative disorders.

Acknowledgements

We thank Laura E. Peters for technical assistance. This study was supported in part by USPHS Grants AG17963 and AG00242.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Aksenov MY, Hasselrot U, Bansal AK, Wu G, Nath A, Anderson C, Mactutus CF, Booze RM. Oxidative damage induced by the injection of HIV-1 Tat protein in the rat striatum. Neurosci. Lett. 2001;305:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01786-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Aoi M, Date I, Tomita S, Ohmoto T. The effect of intrastriatal single injection of GDNF on the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system in hemiparkinsonian rats: behavioral and histological studies using two different dosages. Neurosci. Res. 2000;36:319–325. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(00)00097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Awasthi D, Church DF, Torbati D, Carey ME, Pryor WA. Oxidative Stress Following Traumatic Brain Injury in Rats. Surgical Neurology. 1997;47:575–581. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(96)00461-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Betarbet R, Sherer TB, Greenamyre JT. Ubiquitin-proteasome system and Parkinson's diseases. Exp. Neurol. 2005;191(Suppl 1):S17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Candelario-Jalil E, Mhadu NH, Al-Dalain SM, Martinez G, Leon OS. Time course of oxidative damage in different brain regions following transient cerebral ischemia in gerbils. Neurosci. Res. 2001;41:233–241. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(01)00282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cass WA. GDNF selectively protects dopamine neurons over serotonin neurons against the neurotoxic effects of methamphetamine. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:8132–8139. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-24-08132.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cass WA, Harned ME, Peters LE, Nath A, Maragos WF. HIV-1 protein Tat potentiation of methamphetamine-induced decreases in evoked overflow of dopamine in the striatum of the rat. Brain Res. 2003;984:133–142. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cass WA, Peters LE, Smith MP. Neuroprotective effects of a single injection of GDNF in a rat model of early Parkinson's disease. Exp. Neurol. 2004;187:205. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chao CC, Lee EH. Neuroprotective mechanism of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor on dopamine neurons: role of antioxidation. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:913–916. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Choi WS, Yoon SY, Oh TH, Choi EJ, O'Malley KL, Oh YJ. Two distinct mechanisms are involved in 6-hydroxydopamine- and MPP+-induced dopaminergic neuronal cell death: role of caspases, ROS, and JNK. J. Neurosci. Res. 1999;57:86–94. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990701)57:1<86::AID-JNR9>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ding YM, Jaumotte JD, Signore AP, Zigmond MJ. Effects of 6-hydroxydopamine on primary cultures of substantia nigra: specific damage to dopamine neurons and the impact of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor. J. Neurochem. 2004;89:776–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gash DM, Zhang Z, Ovadia A, Cass WA, Yi A, Simmerman L, Russell D, Martin D, Lapchak PA, Collins F, Hoffer BJ, Gerhardt GA. Functional recovery in parkinsonian monkeys treated with GDNF. Nature. 1996;380:252–255. doi: 10.1038/380252a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gong L, Wyatt RJ, Baker I, Masserano JM. Brain-derived and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factors protect a catecholaminergic cell line from dopamine-induced cell death. Neurosci. Lett. 1999;263:153–156. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Grondin R, Cass WA, Zhang Z, Stanford JA, Gash DM, Gerhardt GA. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor increases stimulus-evoked dopamine release and motor speed in aged rhesus monkeys. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:1974–1980. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01974.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hall ED, Detloff MR, Johnson K, Kupina NC. Peroxynitrite-mediated protein nitration and lipid peroxidation in a mouse model of traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2004;21:9–20. doi: 10.1089/089771504772695904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hudson J, Granholm AC, Gerhardt GA, Henry MA, Hoffman A, Biddle P, Leela NS, Mackerlova L, Lile JD, Collins F, Hoffer BJ. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor augments midbrain dopaminergic circuits in vivo. Brain Res. Bull. 1995;36:425–432. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)00224-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Iannotti C, Ping Zhang Y, Shields CB, Han Y, Burke DA, Xu XM. A neuroprotective role of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor following moderate spinal cord contusion injury. Exp. Neurol. 2004;189:317–332. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ilic TV, Jovanovic M, Jovicic A, Tomovic M. Oxidative stress indicators are elevated in de novo Parkinson's disease patients. Funct. Neurol. 1999;14:141–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jellinger KA. Cell death mechanisms in Parkinson's disease. J. Neural Transm. 2000;107:1–29. doi: 10.1007/s007020050001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Jeon BS, Jackson-Lewis V, Burke RE. 6-Hydroxydopamine lesion of the rat substantia nigra: time course and morphology of cell death. Neurodegeneration. 1995;4:131–137. doi: 10.1006/neur.1995.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kearns CM, Cass WA, Smoot K, Kryscio R, Gash DM. GDNF protection against 6-OHDA: time dependence and requirement for protein synthesis. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:7111–7118. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-18-07111.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kearns CM, Gash DM. GDNF protects nigral dopamine neurons against 6-hydroxydopamine in vivo. Brain Res. 1995;672:104–111. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)01366-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kikuchi A, Takeda A, Onodera H, Kimpara T, Hisanaga K, Sato N, Nunomura A, Castellani RJ, Perry G, Smith MA, Itoyama Y. Systemic increase of oxidative nucleic acid damage in Parkinson's disease and multiple system atrophy. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002;9:244–248. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kirik D, Rosenblad C, Bjorklund A. Characterization of Behavioral and Neurodegenerative Changes Following Partial Lesions of the Nigrostriatal Dopamine System Induced by Intrastriatal 6-Hydroxydopamine in the Rat. Exper. Neurol. 1998;152:259–277. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kirik D, Rosenblad C, Bjorklund A. Preservation of a functional nigrostriatal dopamine pathway by GDNF in the intrastriatal 6-OHDA lesion model depends on the site of administration of the trophic factor. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2000;12:3871–3882. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Klein SM, Behrstock S, McHugh J, Hoffmann K, Wallace K, Suzuki M, Aebischer P, Svendsen CN. GDNF delivery using human neural progenitor cells in a rat model of ALS. Hum. Gene. Ther. 2005;16:509–521. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kramer BC, Mytilineou C. Alterations in the cellular distribution of bcl-2, bcl-x and bax in the adult rat substantia nigra following striatal 6-hydroxydopamine lesions. J. Neurocytol. 2004;33:213–223. doi: 10.1023/b:neur.0000030696.62829.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lotharius J, Dugan LL, O'Malley KL. Distinct mechanisms underlie neurotoxin-mediated cell death in cultured dopaminergic neurons, J. Neurosci. 1999;19:1284–1293. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-04-01284.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Maguire-Zeiss KA, Short DW, Federoff HJ. Synuclein, dopamine and oxidative stress: co-conspirators in Parkinson's disease? Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2005;134:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mattson MP, Duan W. “Apoptotic” biochemical cascades in synaptic compartments: roles in adaptive plasticity and neurodegenerative disorders. J. Neurosci. Res. 1999;58:152–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mattson MP, Keller JN, Begley JG. Evidence for synaptic apoptosis. Exp. Neurol. 1998;153:35–48. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].McGrath LT, McGleenon BM, Brennan S, McColl D, McILroy S, Passmore AP. Increased oxidative stress in Alzheimer's disease as assessed with 4-hydroxynonenal but not malondialdehyde. QJM. 2001;94:485–490. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/94.9.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Patel NK, Bunnage M, Plaha P, Svendsen CN, Heywood P, Gill SS. Intraputamenal infusion of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in PD: a two-year outcome study. Ann. Neurol. 2005;57:298–302. doi: 10.1002/ana.20374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Pedersen WA, Fu W, Keller JN, Markesbery WR, Appel S, Smith RG, Kasarskis E, Mattson MP. Protein modification by the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal in the spinal cords of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Ann. Neurol. 1998;44:819–824. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Poon HF, Joshi G, Sultana R, Farr SA, Banks WA, Morley JE, Calabrese V, Butterfield DA. Antisense directed at the Abeta region of APP decreases brain oxidative markers in aged senescence accelerated mice. Brain Res. 2004;1018:86–96. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Przedborski S, Ischiropoulos H. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: weapons of neuronal destruction in models of Parkinson's disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2005;7:685–693. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Serra JA, Dominguez RO, de Lustig ES, Guareschi EM, Famulari AL, Bartolome EL, Marschoff ER. Parkinson's disease is associated with oxidative stress: comparison of peripheral antioxidant profiles in living Parkinson's, Alzheimer's and vascular dementia patients. J. Neural Transm. 2001;108:1135–1148. doi: 10.1007/s007020170003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Shastry BS. Parkinson disease: etiology, pathogenesis and future of gene therapy. Neurosci. Res. 2001;41:5–12. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(01)00254-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Slevin JT, Gerhardt GA, Smith CD, Gash DM, Kryscio R, Young B. Improvement of bilateral motor functions in patients with Parkinson disease through the unilateral intraputaminal infusion of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor. J. Neurosurg. 2005;102:216–222. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.2.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Smith MP, Cass WA. Oxidative stress and dopamine depletion in an intrastriatal 6-hydroxydopamine model of Parkinson's disease. Neuroscience. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.10.004. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Stadtman ER. Importance of individuality in oxidative stress and aging. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002;33:597–604. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00904-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Theodore S, Cass WA, Maragos WF. Methamphetamine and human immunodeficiency virus protein tat synergize to destroy dopaminergic terminals in the rat striatum. Neuroscience. 2006;137:925–935. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Tomac A, Widenfalk J, Lin LF, Kohno T, Ebendal T, Hoffer BJ, Olson L. Retrograde axonal transport of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in the adult nigrostriatal system suggests a trophic role in the adult. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:8274–8278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Toth G, Yang H, Anguelov RA, Vettraino J, Wang Y, Acsadi G. Gene transfer of glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor and cardiotrophin-1 protects PC12 cells from injury: involvement of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase pathways. J. Neurosci. Res. 2002;69:622–632. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Uchida K. 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal: a product and mediator of oxidative stress. Prog. Lipid Res. 2003;42:318–343. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(03)00014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ugarte SD, Lin E, Klann E, Zigmond MJ, Perez RG. Effects of GDNF on 6-OHDA-induced death in a dopaminergic cell line: modulation by inhibitors of PI3 kinase and MEK. J. Neurosci. Res. 2003;73:105–112. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Venero JL, Revuelta M, Cano J, Machado A. Time course changes in the dopaminergic nigrostriatal system following transection of the medial forebrain bundle: detection of oxidatively modified proteins in substantia nigra. J. Neurochem. 1997;68:2458–2468. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68062458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Wang Y, Lin SZ, Chiou AL, Williams LR, Hoffer BJ. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor protects against ischemia-induced injury in the cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:4341–4348. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04341.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Zuch CL, Nordstroem VK, Briedrick LA, Hoernig GR, Granholm AC, Bickford PC. Time course of degenerative alterations in nigral dopaminergic neurons following a 6-hydroxydopamine lesion. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000;427:440–454. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001120)427:3<440::aid-cne10>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]