Abstract

Adolescent ego-development trajectories were related to close-relationship outcomes in young adulthood. An adolescent sample completed annual measures of ego development from ages 14 through 17. The authors theoretically determined and empirically traced five ego-development trajectories reflecting stability or change. At age 25, the sample completed a close-relationship interview and consented for two peers to rate the participants’ego resiliency and hostility. Participants who followed the profound-arrest trajectory in adolescence reported more mundane sharing of experiences, more impulsive or egocentric conflict-resolution tactics, and less mature interpersonal understanding in their young adult relationships, and their young adult peers described these participants as more hostile. Participants who attained or maintained higher levels of ego development in adolescence reported more complex sharing of experiences, more collaborative conflict-resolution strategies, and greater interpersonal understanding, and their young adult peers rated them as less hostile and as more flexible.

Keywords: ego development, close relationships, longitudinal research

In Loevinger’s model of ego development, as children develop into adolescents and adults, they can hold increasingly complex orientations to the self and to the interpersonal world (Loevinger 1976, 1993). These orientations fall along a continuum where each stage marks “a more differentiated perception of one’s self, of the social world, and the relations of one’s thoughts and feelings to those of others” (Candee, 1974, p. 621). Loevinger’s conceptualization of ego development has been a central perspective in our 25-year longitudinal project because of its theoretical relevance to intrapsychic and to psychosocial questions and because of its linked, psychometrically strong assessment procedure (Hauser, 1976, 1993). Drawing from our study of high-and low-risk adolescents, we have delineated different ego-development trajectories throughout adolescence. The aim of this article is to begin to explore how these trajectories relate to close-relationship outcomes in young adulthood.

Developmental hallmarks of the adolescent years include the expanding capacity for formal operational thought, which allows for more abstract internal representations of the self and of others, the elaboration of self-identity and of associated moral and interpersonal values, and the balance between autonomy and relational intimacy (e.g., Allen, Hauser, O’Connor, & Bell, 1994; Collins, 1990; Steinberg, 1990). These key adolescent issues reflect aspects of ego development. Early stages of ego development are marked by a sense of external control, an egocentric view of the environment, and limited abilities to relate to others (Hauser, 1991). Later stages mark a progression toward internal control, an appreciation of subtle differences among people and events, and strengths involved in forming and in sustaining intimate, collaborative relationships (Hauser, 1991).

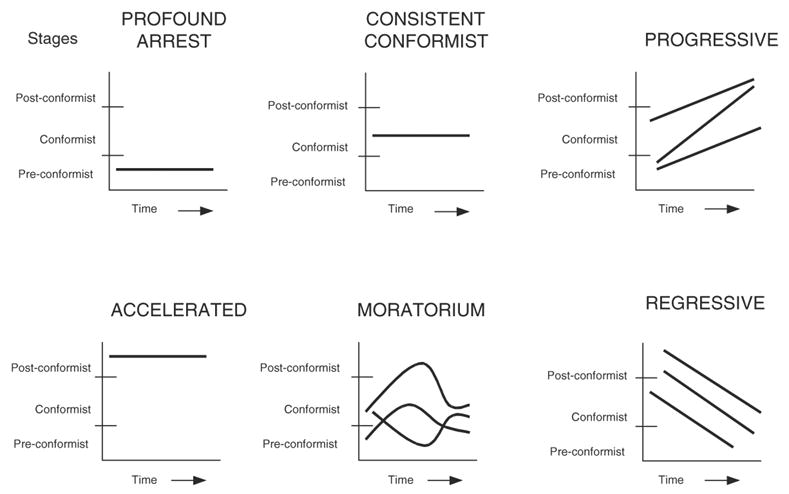

Using theoretically derived definitions (Erikson, 1958; Hauser, 1991; Loevinger, 1976), we identified different ego-development trajectories that adolescents might follow over time. These trajectories allow us to capture individual differences that exist in the timing and the extent of ego development (Westenberg & Gjerde, 1999). One ego-development trajectory is profound arrest (Hauser, 1991). Adolescents who follow this trajectory remain at the lowest, or preconformist, level of ego development throughout their teenage years. These adolescents tend to be egocentric, concentrating on satisfying their own needs or impulses. They manipulate relationships with parents or with peers to meet these needs and impulses. Arrested adolescents have a black-and-white view of other people’s perceptions and feelings, such as the notion that “they are for me or against me.” They tend to have an opportunistic moral style and to try things if they think they can get away with them. Adolescents who follow this path may remain self-protective into young adulthood. Westenberg and Gjerde (1999) found that adolescents who received relatively immature ego-development scores at age 14 later received low ego development scores at age 23. These adolescents may be most at risk for interpersonal difficulties because of their restricted range of emotional responses and their simplistic thinking about others.

A second trajectory is consistent conformist (Hauser, 1991). Adolescents who follow this trajectory remain at the middle, or conformist, level of ego development throughout their teenage years. These adolescents have a strong wish to belong, so they accept and rarely question social rules. Conforming adolescents have loyal and cooperative relationships with parents and with peers. They are becoming more aware of other people’s perceptions and feelings, but their awareness may be superficial or guided by clichés. Adolescents who follow this trajectory are likely to continue to have smooth interpersonal relationships in young adulthood, but their relationships may seem somewhat superficial if they do not move beyond their preoccupations with acceptance and with following group norms.

A third trajectory is accelerated (Hauser, 1991). Adolescents who follow this trajectory remain at the highest, or postconformist, level of ego development throughout their teenage years. These adolescents adhere to norms based on self-evaluated inner standards rather than on stereotypes or group norms. They value both individuality and mutual relationships with parents and with friends, understanding and appreciating individual differences among other people’s perceptions and feelings. They can discern and articulate so-called shades of gray and paradox. Adolescents who follow this trajectory tend to have interpersonal relationships marked by self-disclosure and by reciprocity (Hauser, 1999), and this is likely to continue when they become young adults.

The remaining ego-development trajectories reflect changes over time. Progressive trajectories capture changes from lower to higher ego-development levels (Hauser, 1991). Adolescents can shift from the lowest to the middle level of ego development or from the preconformist to the conformist level. These adolescents are moving from the impulsive or opportunistic level to the more socially conventional level. Adolescents who demonstrate this midlevel progression may have young adult relationships similar to those of the conformist adolescents. Adolescents could also shift from the preconformist or conformist levels to the highest postconformist level. This reflects changes from egocentric or socially conventional ideas to more original or individualistic insights and behaviors. In young adulthood, these adolescents may be similar to those who followed the accelerated trajectory (Westenberg & Gjerde, 1999), and therefore have similar relationship outcomes.

A fifth trajectory is moratorium (Hauser, 1991). Adolescents who follow this unsteady trajectory move up and/or down across ego-development levels. Their views on social conventions and their understanding of parents’ or of peers’ perceptions and feelings may vary dramatically over time. The oscillations in ego development across adolescence make it difficult to predict young adult functioning in close relationships. A final possible trajectory is regression, or slipping from higher levels of ego development to lower levels of ego development (Hauser, 1991). Adolescents who regress may be at risk for interpersonal difficulties in their young adult relationships because they are falling back to a more egocentric or stereotyping style. All of the ego development trajectories are depicted schematically in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Adolescent ego-development trajectories.

These ego-development trajectories reflect intrapsychic tendencies of thought, feelings, and actions about the self and about others that may influence functioning in subsequent close relationships. Relationship dynamics, in part, are manifestations of individual differences (e.g., Neyer & Asendorpf, 2001; Robins, Caspi, & Moffit, 2002; Watson, Hubbard, & Wiese, 2000). For example, Robins et al. (2002) found young adults who easily experience pleasurable emotions, value closeness, and view life as a positive experience (positive emotionality), who conform to social norms (constraint), and who are less prone to fear, anger, or reactivity (negative emotionality) tend to have happier, nonabusive relationships. These relations held for both men and women and generalized across different relationship partners over time.

Adolescents who achieve higher levels of ego development may have a greater capacity for close relationships. Several studies using combinations of self-report and observational or naturalistic data find that higher levels of ego development are associated with greater nurturance, interpersonal sensitivity, valuing of individuality, empathy, and inner control (e.g., Hauser, 1978; Hauser et al., 1984; Helson & Wink, 1987; Valliant & McCullough, 1987). These qualities promote successful intimate relationships (Collins & Sroufe, 1999; Gottman & Levenson, 1992; Rice, 1990). Conversely, adolescents who remain at lower levels of ego development may face frustration and limitation in their close relationships. These individuals may be more likely to engage in more destructive patterns of conflict, such as expressing contempt, belligerence, or defensiveness (Gottman, Coan, Carrère, & Swanson, 1998).

The goal of this article is to use ego-development trajectories to address the following exploratory research questions about close relationship outcomes in young adulthood:

Do adolescents with differing ego-development trajectories vary in how they reflect on and report acting in their subsequent close relationships as young adults? We hypothesized that adolescents who followed profound-arrest trajectories would report continued difficulties in negotiating and in understanding close peer relationships, whereas those who attained or maintained the highest level of ego development would be most adept at negotiating and at understanding these relationships (Hauser, 1999; Schultz & Selman, 1998).

When adolescents with differing ego-development trajectories reach young adulthood, do the peers with whom they have close relationships view them in different ways? We hypothesized that adolescents who followed a profound-arrest trajectory would be viewed as more rigid and hostile by their peers, whereas those who attained or maintained the highest level of ego development would be seen as more flexible, positive, and understanding (Hauser, 1999; Westenberg & Block, 1993).

METHOD

Participants

The study is drawn from a longitudinal project based on two samples recruited in adolescence (M age = 14.43, SD = .87) from a local public high school (N = 76) and from a private psychiatric hospital (N = 70). The purpose of recruiting these two samples was to capture a broad range of psychosocial functioning. Psychiatric hospitalization in adolescence served as a potential marker of lower levels of ego development. Hospitalized adolescents carried DSM-III diagnoses such as conduct or oppositional defiant disorder (50%), depressive disorders (22.9%), anxiety disorders (5.7%), or other disorders (20.6%), but none was psychotic or organically impaired. The two samples did not differ significantly in terms of age, gender, birth order, or family structure and differed only moderately in socioeconomic standing (higher for the high school sample). Participants were predominantly White and from upper middle-class families (M Hollingshead 1975 socioeconomic status = 2.07, SD = 1.26). The first wave of observations included a baseline and two to three additional adolescent and family assessments from ages 14 to 17.

The second wave of the study took place when participants reached young adulthood (M age = 25.7 years, SD = .95). Only three participants refused to participate in the second wave, and one had died; there appeared to be no significant differences on demographic or on psychiatric measures between those who participated and those who did not at age 25. Eighty-six percent of the high school sample and 70% of the psychiatric sample were employed. Thirty-six percent of the high school sample and 55% of the psychiatric sample were married or living with a romantic partner.

Adolescent Procedure

Adolescents completed annual assessments from ages 14 to 17 in private classrooms at their high school or in private offices at the psychiatric hospital. The assessments included individual interviews, paper-and-pencil measures, and structured family observations.

Adolescent Measures

From ages 14 through 17, we collected annual measures of ego development using the Washington University Sentence Completion Test (SCT) (Loevinger & Wessler, 1970). Expert coders rated responses to the 36 SCT stems (e.g., “Raising a family . . .,” “My conscience bothers me if . . . ”) separately and then reassembled the items to assign a specific ego-development stage (i.e., impulsive, self-protective, conformist, self-aware, conscientious, individualistic, or autonomous). The stage score for each participant was then subsequently assigned to one of three overall ego-development levels: (a) preconformist (impulsive, self-protective, self-protective or conformist), (b) conformist (conformist, self-aware), or (c) postconformist (conscientious, conscientious and/or individualistic, and autonomous).

Based on operational definitions of theoretically meaningful developmental patterns, we assigned each adolescent to an ego-development trajectory by tracing the overall ego-development levels across three to four adolescent time points. We identified three steady trajectories within our sample: (a) accelerated, or unchanging postconformist ego-development levels (high school n = 7; psychiatric sample n = 1); (b) consistent conformist, or unchanging, conformist-level stage scores (high school n = 18; psychiatric n = 1); and (c) profound arrest, or unchanging, preconformist-level stage scores (high school n = 7; psychiatric n = 30). We also identified three trajectories that reflect change: (a) midlevel progression, or a steady shift from preconformist to conformist (high school n = 13; psychiatric n = 16); (b) high-level progression, or a steady shift from conformist to postconformist (high school n = 11; psychiatric n = 4); and (c) moratorium, or unsteady shifts across the three levels (high school n = 14; psychiatric n = 11).

Two theoretically possible change trajectories were not found within our sample: (a) regression, or a steady shift from higher ego-development levels to lower levels, and (b) low- to high-level progression, or a steady shift from the preconformist to the postconformist level. Trajectories were not completed for 13 participants who were missing two or more ego-developmental level scores, and these participants were excluded from analyses. Because of the new and more stringent requirement of needing three or more ego-development level scores to assign a trajectory score, the ego-development trajectory groups in this report differ slightly from past reports (Hauser, 1991).

Young Adult Procedure

At age 25, participants completed an assessment in private offices at the research site or close to their residences. The assessment included individual interviews and paper-and-pencil measures. Participants also shared information about friends or romantic partners to whom they felt closest. With each participant’s permission, two of these peers were contacted and asked to describe the participant using a variation of the California Adult Q-sort (Block, 1978) used by Kobak and Sceery (1988).

Young Adult Measures

Developmental Relationship Scales

Participants completed the Close Peer Relationship Interview (Schultz, 1993), a semistructured interview designed to explore intimacy and autonomy in friendships and/or in romantic relationships. Participants answered questions about two specific relationships: those with a current romantic partner and a close friend, or those with two close friends if they did not have a current romantic relationship. The Developmental Relationship Scales (Schultz, 1993; Schultz & Selman, 1998) were constructed from the Close Peer Relationship Interview data by adapting previous developmental scales based on the interpersonal theory devised by Selman and his colleagues (Selman, 1980; Selman & Schultz, 1990). The scales assess self-reported autonomy and relatedness interactions and reflections about the young adults’ two closest peer relationships.

Two trained coders scored each Close Peer Relationship Interview with the Developmental Relationship Scales and then met together to reach a consensus on the codes. Interrater reliability computed on the preconsensus scores with Cohen’s kappa ranged from .47 to .67. Consensus scores are used in the following analyses. The following scales included in this article ranged from the lowest level (zero) to the highest level (four), based on the participants’ capacities to coordinate social perspectives.

Shared experience: Defined as the relatively harmonious experiencing of emotional and physical connections with another person through self-disclosure, doing things together, and spending time together. This intimacy-oriented scale focuses on incidents and on patterns of shared experiences that the individual reports when describing actual interactions with the other person. Low-level scores reflect limited emotional sharing while engaging in primarily practical or mundane activities. High-level scores reflect open self-disclosure about personal and relationship issues and a rich sharing of interests, activities, and values.

Interpersonal negotiation: Focuses on incidents and patterns of conflict resolution that the individual reports when describing actual interactions with the other person. Interpersonal negotiation strategies are defined as the ways in which individuals in situations of social conflict deal with the self and with another person to gain control over inner and interpersonal disequilibria. Low-level scores indicate use of impulsive, egocentric strategies to get one’s way (e.g., hitting or grabbing) or to avoid harm (e.g., hiding). High-level scores indicate more cooperative and collaborative strategies, such as candid sharing and negotiation, to resolve conflict.

Interpersonal understanding: Reflects what the developing individual understands to be the core psychological and social qualities of persons and of relationships. Conceptually, this construct represents a reflective social cognitive competency that is necessary but not sufficient for mature developmental levels of interpersonal action. An important facet of this scale is perspective taking and the ability to understand how different perspectives may color the relationship. Low-level scores reflect limited or concrete perspective taking, whereas higher scores reflect greater awareness of different points of view.

California Q-sort

Participants consented for the project to contact two peers who knew them well to ask them to rate the participants using a variation of the California Q-sort (Block, 1978) used by Kobak and Sceery (1988). For 13 participants, peers did not provide ratings. For two participants, only one peer provided ratings, and these single peer ratings are included in the analyses. The response rate from peers did not differ according to participants’ genders or psychiatric histories. The following two scales were derived from the peer Q-sort:

Ego resilience: The pattern of each participant’s averaged peer ratings were correlated with Block’s (1978) prototype sort for an ego-resilient individual, which reflects being cognitively and emotionally well adjusted and interpersonally effective. The resulting correlation, ranging from −1.00 to +1.00, represents the participant’s peer-rated ego-resiliency score.

Hostility. Using Kobak and Sceery’s (1988) Q-sort scoring procedures, a hostility mega-item was created from peer-rating averages. The mega-item sums eight Q-sort items related to hostility, such as “has hostility toward others,” “expresses hostile feelings directly,” and “is subtly negativistic.” The hostility items had good internal consistency (α = .76), and peer ratings were moderately correlated (r for composite ratings = .53).

RESULTS

Overall sample means and standard deviations of the outcome variables are presented in Table 1, and intercorrelations among outcome variables are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Young Adult Outcome Measures (N = 130)

| Measure | N | Min. | Max. | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shared experience | 130 | 1.00 | 3.50 | 2.14 | 0.58 |

| Interpersonal negotiation | 130 | 0.50 | 2.50 | 1.40 | 0.44 |

| Interpersonal understanding | 130 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 2.44 | 0.68 |

| Ego resiliency | 122 | −0.58 | 0.78 | 0.38 | 0.30 |

| Hostility | 122 | 12.00 | 59.00 | 28.19 | 9.25 |

NOTE: Min. = minimum; Max. = maximum.

TABLE 2.

Intercorrelations Among Close-Peer Relationships and California Q-Sort Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Shared experience | — | .71*** | .58*** | .32** | −.14 |

| 2. Interpersonal negotiation | — | .48*** | .39*** | −.29* | |

| 3. Interpersonal understanding | — | .33** | −.25* | ||

| 4. Ego resilience | — | −.60*** | |||

| 5. Hostility | — |

p < .05.

p < .001.

p < .0001.

Subjective experience of close relationships as associated with ego-development trajectories

Analyses of variance with trajectory group as the independent variable and The Close Relationship Scales as the dependent variables yielded the following results (see Table 3). Tukey-Kramer tests were used for post hoc multiple comparisons.

TABLE 3.

Means of Close-Relationship Variables by Ego-Development Trajectory

| Ego-Development Trajectory

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Profound Arrest (n = 36) | Consistent Conformist (n = 19) | Accelerated (n = 8) | Midlevel Progression (n = 28) | High-Level Progression (n = 15) | Moratorium (n = 24) | F |

| Shared experience | 1.80 (.52) a,b,c | 2.32 (.49) a | 2.85 (.36) b,d,e | 2.05 (.48) d | 2.52 (.59) c | 2.13 (.53) e | 8.58*** |

| Interpersonal negotiation | 1.12 (.37) a,b,c,d | 1.60 (.45) a | 1.87 (.45) b, e | 1.36 (.34) e | 1.50 (.51) c | 1.46 (.38) d | 6.91*** |

| Interpersonal understanding | 2.14 (.55) a | 2.42 (.55) b | 3.56 (.55) a,b,c,d,e | 2.50 (.51) c | 2.63 (.81) d | 2.33 (.67) e | 7.92*** |

NOTE: Values in parentheses represent standard deviations. Row means with a common subscript are statistically different, p < .05.

p < .0001.

Shared experience: The profound arrest trajectory group (M = 1.80) from adolescence received significantly lower shared experience scores in young adulthood than did the accelerated (M = 2.85, p < .0001), the high-level progression (M = 2.52, p < .001), and the conformist (M = 2.32, p < .01) trajectory groups but not the midlevel-progression (M = 2.05) or the moratorium (M = 2.13) groups. In addition, the accelerated trajectory group received significantly higher shared experience scores than did the profound-arrest (p < .0001), the midlevel- progression (p < .01), and the moratorium (p < .01) trajectory groups but not the high-level progression or the consistent conformist trajectory groups. Overall, F(5, 124) = 8.58, p < .0001.

Interpersonal negotiation: The profound arrest ego development trajectory group (M = 1.12) received significantly lower interpersonal negotiation scores in young adulthood than did the accelerated (M = 1.87 p < .0001), the high-level progression (M = 1.50, p < .05), the conformist (M = 1.60, p < .001), and the moratorium (M = 1.46, p < .05) trajectory groups but not the midlevel-progression group (M = 1.36). In addition, the accelerated trajectory group received significantly higher interpersonal negotiation scores in young adulthood than did the profound arrest (p < .0001) and the midlevel-progression (p < .05) trajectory groups but not the high-level progression, the consistent conformist, or the moratorium trajectory groups. Overall, F(5, 124) = 6.91, p < .0001.

Interpersonal understanding: The accelerated ego-development trajectory group (M = 3.56) in adolescence received significantly higher interpersonal understanding scores in young adulthood than did the high-level progression (M = 2.63, p < .01), the midlevel-progression (M = 2.50, p < .001), the conformist (M = 2.42, p < .001), the profound arrest (M = 2.14, p < .0001), and the moratorium (M = 2.33, p < .0001) trajectory groups. Overall, F(5, 124) = 7.92, p < .0001.

Close peers’observations of the adolescents as young adults

Analyses of variance with trajectory group as the independent variable and the California Q-sort peer ratings as the dependent variables yielded the following results (See Table 4). Tukey-Kramer tests were used for post hoc multiple comparisons.

TABLE 4.

Means of California Q-Sort Variables by Ego-Development Trajectory

| Ego-Development Trajectory

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profound Arrest (n = 30) | Consistent Conformist (n = 19) | Accelerated (n = 8) | Midlevel Progression (n = 27) | High-Level Progression (n = 14) | Moratorium (n = 24) | F | |

| Ego resilience | 0.22 (0.32) a | 0.62 (0.08) a,b | 0.43 (0.18) | 0.34 (0.31) b | 0.38 (0.36) | 0.41 (0.29) | 4.82** |

| Hostility | 34.38 (10.08) a,b,c | 23.84 (5.64)a | 25.38 (3.92) | 26.91 (8.96) b | 25.39 (10.67) c | 27.92 (7.91) | 4.65** |

NOTE: Values in parentheses represent standard deviations. Row means with a common subscript are statistically different, p < .05.

p < .001.

Ego resilience: The consistent conformist ego-development trajectory group (M = .62) in adolescence received significantly higher ego-resiliency Q-sort ratings from their peers in young adulthood than did the midlevel-progression (M = .34, p < .05) and the profound arrest (M = .22, p < .0001) trajectory groups. Overall, F(5, 116) = 4.82, p < .001.

Hostility: The arrest-ego trajectory group (M = 34.38) received significantly higher hostility scores from their peers in young adulthood than did the high-level progression (M = 25.39, p < .05), the midlevel-progression (M = 26.91, p < .05), and the consistent conformist (M = 23.84, p < .001) trajectory groups and marginally higher scores than did the accelerated (M = 25.38, p < .10) and the moratorium (M = 27.92, p < .10) trajectory groups. Overall, F(5, 116) = 4.65, p < .001.

DISCUSSION

Adolescent ego trajectories appear to predict facets of young adults’close relationships. Adolescents following the arrest trajectory, when young adults, reported less emotional sharing and described more mundane activities with their young adult peers than those on other trajectories, except for those who had also begun at the preconformist level but progressed to the conformist level of ego development or those who had unsteady trajectories. Those had who maintained the conformist level of ego development, as well as those who attained or maintained the postconformist level of ego development, reported the most complex and intimate shared experiences in their subsequent relationships.

Adolescents who followed the profound arrest trajectory were also most likely to report impulsive or egocentric strategies to solve or to avoid conflicts in their young adult relationships. In contrast, the adolescents who followed the accelerated trajectory were most likely to describe candid sharing and open negotiation in their young adult close relationships. Those on the accelerated path were also most likely to describe different perspectives within their young adult relationships and how these perspectives influenced their relationships.

We also found some convergence between self-report and peer descriptions of relationship functioning. The peers of the young adults described those who had followed the arrest trajectory as being more hostile, and those who had followed this trajectory also reported being more impulsive and egocentric in their relationships. The young adults’ friends also rated those men and women who had followed the conformist trajectory or attained or maintained the postconformist level as more flexible and positive (ego resiliency), and those who followed these trajectories reported richer relationship experiences and better interpersonal skills. An important future direction will be to understand the current relationship contexts in which the individual is embedded (Reis, Collins, & Berscheid, 2000) and how these relationship transactions may enhance, sustain, or inhibit ego development.

Another important future direction will be examining how concurrent ego development in young adulthood may moderate or mediate the effects of the adolescent ego-development trajectories on young adult relationship outcomes. Preliminary analyses within our data set suggest concurrent ego development may play a role, but developmental history seems to matter. For example, we found that participants who shifted from the arrest trajectory in adolescence to the conformist level in young adulthood obtained higher peer ego-resiliency ratings than did those who remained at the lowest level. However, they did not obtain ego-resiliency ratings as high as participants who had followed the consistent conformist trajectory in adolescence and remained at the conformist level in young adulthood. This preliminary finding highlights the salience of adolescent development and the value of collecting longitudinal data. It may also suggest that individuals who are at lower levels of ego development during adolescence may miss critical opportunities to gain experience and skill in social relationships, such that even if their levels of ego development later catch up, they may still remain somewhat behind in terms of their social interactions.

We will continue to refine our adolescent trajectories (e.g., tease apart the moratorium and the progression trajectories to compare early- vs. late-adolescent shifts to different ego-development levels) and to conceptualize and empirically determine new adolescent-to-adult developmental trajectories. As we extend the period of development captured by our trajectories into young adulthood, we may find regression and low- to high-level progression trajectories that were not observed in adolescence, although other data sets examining the stability of ego development between adolescence and young adulthood suggest that these large gains or declines are less likely (Westenberg & Gjerde, 1999). We also hope to examine the dynamic interplay between psychopathology and ego development (Noam, 1998). Given that each ego-development trajectory included participants from both the high- and the low-risk samples and that neither all psychiatric patients nor all nonpatients follow a single adolescent ego-development trajectory, it is clear that the trajectories are not simply a proxy for serious psychopathology. In future analyses, we plan to examine more specific psychopathology questions, including whether acute versus chronic externalizing and/or internalizing disorders may mediate or moderate relations between ego development and close-relationship outcomes.

These preliminary findings suggest that adolescent ego-development trajectories may influence subsequent functioning in close young adult relationships. We encourage other researchers to replicate our findings in larger, representative samples to enhance understanding of the mechanisms and the processes at play between paths of adolescent ego development and of close relationship outcomes over time.

Footnotes

This study was funded by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health to Stuart T. Hauser (NO. R01 MH44934-03) and to Katherine H. Hennighausen (No. T32 MH 016259).

Contributor Information

Stuart T. Hauser, Harvard Medical School

Rebecca L. Billings, Judge Baker Children’s Center

Lynn Hickey Schultz, Harvard University.

Joseph P. Allen, University of Virginia

References

- Allen JP, Hauser ST, O’Connor TG, Bell KL. Prediction of peer-rated adult hostility from autonomy struggles in adolescent-family interactions. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:123–137. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402001074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block J. The Q-sort method of personality assessment and psychiatric research. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Candee D. Ego development aspects of new left ideology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1974;30:620–630. doi: 10.1037/h0037437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA. Parent-child relationships in the transition to adolescence: Continuity and change in interaction, affect, and cognition. In: Montemayor R, Adams GR, Gullotta TP, editors. From childhood to adolescence: A transitional period? Advances in Adolescent Development. Vol. 2. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. pp. 85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Sroufe LA. Capacity for intimate relationships: A developmental construction. In: Furman W, Brown BB, Feiring C, editors. Contemporary perspectives in adolescent romantic relationships. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 125–147. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity and the life cycle. Psychological Issues. 1958;1(1):1–171. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Coan J, Carrère S, Swanson C. Predicting marital happiness and stability from newlywed interactions. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Levenson RW. Marital processes predictive of later dissolution: Behavior, physiology, and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:221–233. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser ST. Loevinger’s model and measure of ego development: A critical review. Psychological Bulletin. 1976;83:928–955. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser ST. Ego development and interpersonal style in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1978;7:333–352. doi: 10.1007/BF01537804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser ST. Adolescents and their families: Paths of ego development. New York: Macmillan; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser ST. Loevinger’s model and measure of ego development: A critical review, 2. Psychological Inquiry. 1993;4(1):23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser ST. Understanding resilient outcomes: Adolescent lives across time and generations. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1999;9(1):1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser ST, Powers SI, Noam GG, Jacobson AM, Weiss B, Follansbee DJ. Familial contexts of adolescent ego development. Child Development. 1984;55:195–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helson R, Wink P. Two conceptions of maturity examined and the findings of a longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:531–541. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.3.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Sceery A. Attachment in late adolescence: Working models, affect regulation and representations of self and others. Child Development. 1988;59:135–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loevinger J. Ego development: Conceptions and theories. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Loevinger J. Ego development: Questions of method and theory. Psychological Inquiry. 1993;4(1):56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Loevinger J, Wessler R. Measuring ego development: Construction and use of a sentence completion test. Vol. 1. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Neyer FJ, Asendorpf JB. Personality-relationship transaction in young adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:1190–1204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noam G. Solving the ego development-mental health riddle. In: Westenberg PM, Blasi A, Cohn LD, editors. Personality development: Theoretical, empirical, and clinical investigations of Loevinger’s conception of ego development. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1998. pp. 271–295. [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT, Collins WA, Berscheid E. The relationship context of human behavior and development. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126(6):844–872. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.6.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice FP. Intimate relationships, marriages, and families. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. It’s not just who you’re with, it’s who you are: Personality and relationship experiences across multiple relationships. Journal of Personality. 2002;70(6):925–964. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.05028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz LH. Manual for scoring young adult close peer relationship interviews with the developmental relationship scales. 1993. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz LH, Selman RL. Ego development and interpersonal development in young adulthood: A between-model comparison. In: Westenberg PM, Blasi A, Cohn LD, editors. Personality development: Theoretical, empirical, and clinical investigations of Loevinger’s conception of ego development. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1998. pp. 181–202. [Google Scholar]

- Selman RL. The growth of interpersonal understanding: Developmental and clinical analyses. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Selman RL, Schultz LH. Making a friend in youth: Developmental theory and pair therapy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Interdependency in the family: Autonomy, conflict, and harmony in the parent-adolescent relationship. In: Feldman S, Elliott G, editors. At the threshold: The developing adolescent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. pp. 255–276. [Google Scholar]

- Valliant GE, McCullough L. The Washington University Sentence Completion Test compared with other measures of adult ego development. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;144:1189–1194. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.9.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Hubbard B, Wiese D. General traits of personality and affectivity as predictors of satisfaction in intimate relationships: Evidence from self and partner-ratings. Journal of Personality. 2000;68:413–449. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westenberg PM, Block J. Ego development and individual differences in personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:792–800. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.4.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westenberg PM, Gjerde PF. Ego development during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood: A 9-year longitudinal study. Journal of Research in Personality. 1999;33:233–252. [Google Scholar]