Overdose on illicit drugs is a substantial and growing public health problem. In New York City (NYC) between 1990 and 2001, overdose deaths increased by 48%, from 541 to 799 fatalities; in contrast, homicides decreased by 71%, from 2,081 to 609 during this same time period.1 Certain populations are at particularly high risk of overdose: among users of single-adult homeless shelters in NYC, overdose morbidity and mortality markedly exceeds rates in the general population.2 Overdose has been identified as a primary cause of excess mortality among substance users with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in NYC.3 A substantial increase in overdose risk has been identified following release from prison or jail, as substance users' tolerance for opioids decreases during incarceration.4–7 Each of these findings reflects a point of potential public health intervention.

Naloxone hydrochloride, an opioid receptor antagonist that can be administered via intramuscular (IM), intranasal (IN), intravenous, or subcutaneous routes, is routinely used by emergency responders to reverse opiate overdose. Naloxone has no agonist properties and, therefore, has no potential for abuse and minimal potential for diversion or misuse.8

This article describes an initiative to provide prefilled naloxone dispensers and overdose-related education and training directly to substance users themselves, to enable them to, if necessary, directly initiate overdose reversal and prevent morbidity and mortality among their peers.8,9 Most overdoses are witnessed by others,10 which provides an opportunity for peers to adopt the role of overdose responder11 in the absence of emergency medical services.

Providing substance users with an antidote to opiates can be considered a harm-reduction strategy. While the ultimate public health goal is to reduce substance use itself, the harm-reduction approach recognizes the imperative to address immediate health risks for individuals who continue to use substances. The key features of harm reduction include: (1) pragmatism: some level of substance use is inevitable in society, and containing and mitigating related harms is more feasible than eliminating use altogether; (2) humanistic values: accepting an individual's decision to use substances respects his or her rights and dignity; (3) a focus on harms: prioritizing reduction of the negative consequences of substance use to the user and others, while neither excluding nor presuming abstinence as the long-term treatment goal; (4) a balance of costs and benefits to the individual and society: identifying and measuring the relative importance of drug-related problems, the associated harms, and costs/benefits for intervention; and (5) a hierarchy of goals: achieving the most immediate and realistic goals, with the immediate focus on substance user engagement to address the most pressing needs.12 In practice, harm reduction offers active substance users practical education and care, health promotion skills, and basic health-care tools in a nonjudgmental framework. In the larger public health framework, immediate access to drug treatment and psychiatric counseling and care for active substance users will also facilitate a reduction in overdose mortality. In the harm-reduction approach, take-home naloxone for active users provides an intervention opportunity for those who are presently unable or unwilling to abstain from substance use.

In the United States, since 2001, several cities and states have initiated overdose prevention programs in user networks that involve prescribing and dispensing naloxone to substance users in tandem with overdose prevention education.9,13 This article describes the development and implementation of the intervention in NYC, including legal barriers and how they were overcome, preliminary outcomes, and issues surrounding future expansion. As a case study of a local experience, this article emphasizes the roles adopted by the various stakeholders (syringe exchange programs [SEPs], harm-reduction advocates, researchers, academics, and city and state governments) and the importance of the collaborative effort.

INITIATIVE SUMMARY

SEPs were legally sanctioned by New York State in 1992 under public health emergency law.14 In 2003, three SEPs in NYC collaboratively sought foundation support for developing and delivering a pilot overdose prevention intervention with participants in their programs. The programs are located in the Lower East Side of Manhattan and in the South Bronx, two of the city's poorest neighborhoods, where overdose mortality is concentrated.15,16 Importantly, the programs received a letter of support for the proposal from the Commissioner of the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYC DOHMH).

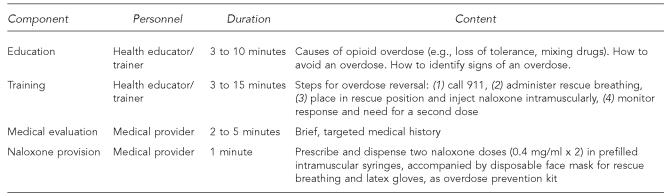

The Tides Foundation awarded $13,013 to the three-program collaborative for the pilot. Staff at the three programs used the funds to research and develop program tools and a training curriculum, to plan an evaluation methodology (baseline surveys for all trainees and follow-up surveys for participants requesting a naloxone refill), and to gather legal and policy advice from academics and programs operating in other localities. The resulting curriculum and protocol of prescribing and dispensing naloxone in prefilled IM syringes were loosely based on similar programs already operating in other areas of the country. The program involves general education, training, and medical evaluation (Figure). Although the education and training components can be delivered individually or to small groups, an individual medical evaluation is necessary for prescribing and dispensing naloxone. The issue of potential medical provider liability associated with prescribing and dispensing take-home naloxone for secondary administration by a layperson (the patient) to another individual was problematic. The programs chose to identify a provider willing to assume this risk, to demonstrate program feasibility despite the liability issue.

Figure.

Opioid overdose prevention program intervention

a Markham Piper T, Rudenstine S, Stancliff S, Sherman S, Nandi V, Clear A, et al. Overdose prevention for injection drug users: lessons learned from naloxone training and distribution programs in New York City. Harm Reduct J 2007;4:3.

However, recruiting a consulting medical provider, given the liability issues (more so than willingness to work in such nontraditional venues as community-based SEPs), proved to be the most challenging aspect of program implementation. NYC DOHMH considered using its own clinical staff for the program, but could not overcome the liability issues. A consulting provider willing to assume this risk was finally secured by the summer of 2004, and the pilot was initiated.17

By 2005, following advocacy by an informal coalition of local harm-reduction advocates, the city legislature funded an expansion of the pilot to all 13 NYC SEPs, adopting the preexisting pilot as the model intervention.

A locally based national advocacy and training organization, Harm Reduction Coalition, is currently contracted by NYC DOHMH to provide technical assistance, training, and continued medical services for the overdose prevention program in NYC. The project's physician provides train-the-trainer sessions, prescribes and dispenses naloxone, and establishes local models of the intervention at each of the 13 SEPs. By October 2006, more than 1,800 program participants had been trained as overdose responders and provided with overdose prevention kits, representing approximately 15% of annual participation in SEPs in NYC. Anecdotally, the initiative has been well-accepted by the programs' staff, participants, and peers.

OUTCOMES

Preliminary evaluation

A preliminary evaluation plan of NYC's overdose prevention program was developed by representatives from the SEPs and by consulting researchers to the Harm Reduction Coalition. Quantitative data was initially collected by research staff (participant baseline and naloxone refill surveys), although subsequently, SEP staff delivering the intervention continued this data collection. Qualitative evaluation was conducted by the external research team (i.e., interviews with participants reporting overdose reversals).

An overdose reversal rate of 3% (25 overdose reversals among 754 trainees provided with kits) was reported for the first six months of program implementation. Notably, although the trainees had received naloxone from the provider as her primary patient, all reports of naloxone administration involved administration by the patient to another, non-patient individual. (Unpublished data, New York Academy of Medicine, Evaluation of Harm Reduction Coalition's overdose prevention initiative, 2005.) The reported reversal rate increased to 7% (104/1,485) after 12 months,13 and to 9% (162/1,800) after 18 months, although substantial underreporting is suspected. Such reports warrant further investigation from the perspective of emergency medical services, to triangulate and confirm program effects. Reported reversal rates (during roughly one- to three-year time periods) from similar programs operating in other U.S. cities ranged from 24% (170/700) reported by trainees in San Francisco, to 14% (131/951) in Baltimore, and 7% (446/6,000) in Chicago.13

Legislative change to address legal barriers

Statewide prescription laws governing the activities of licensed medical providers in New York State are similar to laws elsewhere in the country: prescriptions are provided for the patient's personal use. As previously described, these statutes prevented the lawful prescribing and dispensing of take-home naloxone for secondary administration—by overdose responders (patients) to others (non-patients)—effectively preventing widespread implementation of the intervention because of provider liability concerns. With the development of the pilot program in 2004, state-level health officials initiated discussions within government for the development of legislation to overcome this legal barrier. External advocates adopted the draft legislation and promoted support for its passage among legislative and key administrative representatives in state government.

Education among legislators was centered on emphasizing the high prevalence of overdose mortality and on the relative safety of naloxone as a prescribed substance, with minimal potential for diversion or misuse.9 Including New York State's Department of Education, which governs medical licensing in both the education campaign and the negotiations process for practice guidelines, proved pivotal in the development of a successful bill. Together, these efforts culminated in the passage of an amendment to the public health law in 2005, legislating standards for opioid overdose prevention programs in New York State.18 Specifically, the law protects the medical provider from potential liability when naloxone prescribed to a patient in the context of an authorized overdose prevention program is secondarily administered to another, non-patient of the provider.19

The new legislation took effect on April 1, 2006. In preparation, the New York State Department of Health's AIDS Institute (NYS DOH-AI) consulted with existing opioid overdose prevention programs in Chicago, Baltimore, New Mexico, and San Francisco, as well as with the NYC program, to develop regulations and protocols.20

Program expansion

To promote further expansion of the intervention, issues pertaining to program implementation are being addressed, including model policies and procedures and training guidelines.20 These developments have resulted in increased interest among non-SEP providers, including methadone treatment and primary-care providers, for implementing the intervention within their practice.

With the state legislative amendment in place, program expansion in response to local findings has also been initiated by NYC DOHMH. Opportunities for overdose prevention program implementation in NYC's adult homeless shelter system and in the city's jails via venue-based public health services and education are currently in an exploratory phase.

FUTURE CHALLENGES

Widespread, sustained program implementation can result in a population-level decline in overdose mortality. In Cook County, Illinois, there has been a 30% reduction in countywide fatal overdoses since the local program began in January 2001,13 and in Baltimore, citywide overdose fatalities decreased by 19% after the program's first year of operation.21 In NYC, the program currently operates with one physician delivering, mentoring, and training both medical providers and staff at programs and venues throughout the city. To meet the challenge of achieving population-level effects, the program must expand into diverse systems of care and must engage and educate diverse risk groups and their social networks.

Challenges limiting widespread dissemination of the strategy reflect the complex effort required to promote and implement this unique, newly regulated public health initiative. Future efforts must address and overcome the constraints of diverse settings where overdose prevention is a critical health issue, including jails, homeless shelters, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) primary-care and community-based service venues. In addition, ongoing program communication and education with the law enforcement community is necessary to increase and maintain awareness and support for the intervention. Finally, more structured, prospective evaluation will be necessary to identify whether the program is successful in reducing overdose mortality and, if so, how this success is best achieved.8

The prefilled IM syringe presents a particular problem for overdose prevention in controlled settings. Syringes are contraband in jails and may present a physical threat to others. Provision of the IM naloxone syringe to inmates upon release also presents a logistical challenge, as a medical visit is required for such provision, and many releases in NYC occur directly from the courts, without a formal discharge process. Provision of naloxone in prefilled IN mucosal atomizer devices may provide a solution,22 although studies show efficacy in only 74% of pre-hospital cases.23 However, despite its failure to be uniformly effective, IN naloxone may provide a viable alternative in this context.

DOHMH health educators at the city jail are currently providing referrals to SEPs as part of discharge planning, so that individuals receiving overdose education and training from this group while they are inmates at the jail are informed about and can obtain naloxone following their release. Additionally, a homeless-outreach provider is offering the intervention via street homeless outreach. DOHMH is working with the NYC Department of Homeless Services to establish a protocol for opioid overdose prevention with users of the single-adult shelter system, which served 33,687 individuals in 2005.

Collaboration has also been initiated with NYC law enforcement, building upon syringe exchange education work conducted by NYS DOH-AI during the last 14 years. Presently, the NYS DOH-AI is working with NYC DOHMH and the New York Police Department to develop and implement a departmental protocol for officers to ensure they are advised of the newly legislated program and to prevent unnecessary confusion and confiscation of naloxone. Successful provision of the intervention depends upon close, ongoing collaboration and communication. To prevent needle stick injury, overdose prevention trainees are advised by programs to inform officers that they are carrying naloxone during a search encounter. Officer training regarding the initiative will be a critical aspect of program implementation.

Expanded participation of the medical community will be paramount. Accessing and educating the diverse medical community for adoption of a new intervention delivered to a vulnerable population may be a difficult and lengthy process. However, a preliminary survey found that 33% of medical providers in NYC would be willing to prescribe naloxone, while 29% were unsure.24 Providers and venues for participation could include emergency departments, community health centers, substance abuse services (e.g., hospital detoxification units, methadone maintenance treatment programs), HIV primary-care providers, and medical centers.

The successful development of an opioid overdose prevention program in NYC has occurred with the progressive and synergistic efforts of the community, researchers, and city and state governments to overcome logistical, funding, and legal barriers to widespread implementation. The local success we have achieved in rapid program development and implementation has relied on the collaborative and complementary efforts of all stakeholders. The intervention now shows promise for addressing and reducing overdose mortality via community-based, public, and medical systems of care in NYC.

Footnotes

[Editor's note: What is especially interesting about this effort by New York is that it took one person to look past the law to get the ball rolling, and then it took the efforts of many inside and outside of government to change the law in order to gain momentum. It demonstrates how important the law can be in progress for public health at the local level.]

REFERENCES

- 1.Coffin PO, Galea S, Ahern J, Leon AC, Vlahov D, Tardiff K. Opiates, cocaine and alcohol combinations in drug overdose deaths in New York City, 1990–98. Addiction. 2003;98:739–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerker B, Bainbridge J, Li W, Kennedy J, Bennani Y, Agerton T, et al. The health of the homeless: a report from New York City's Departments of Health and Mental Hygiene and Homeless Services. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfeiffer M, Hanna DB, Begier EM, Sepkowitz KA, Torian LV, Sackoff JE. Persistent contribution of substance abuse to excess mortality among persons with AIDS in New York City, 1999–2003. Presentation at the 16th International AIDS Conference; 2006 Aug 13–18; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, Heagerty PJ, Cheadle A, Elmore JG, et al. Release from prison—a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:157–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ochoa KC, Davidson PJ, Evans JL, Hahn JA, Page-Shafer K, Moss AR. Heroin overdose among young injection drug users in San Francisco. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;80:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bird SM, Hutchinson SJ. Male drugs-related deaths in the fortnight after release from prison: Scotland, 1996–99. Addiction. 2003;98:185–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seaman SR, Brettle RP, Gore SM. Mortality from overdose among injecting drug users recently released from prison: database linkage study. BMJ. 1998;316:426–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7129.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sporer KA, Kral AH. Prescription naloxone: a novel approach to heroin overdose prevention. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:172–7. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baca CT, Grant KJ. Take-home naloxone to reduce heroin death. Addiction. 2005;100:1823–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tracy M, Piper TM, Ompad D, Bucciarelli A, Coffin PO, Vlahov D, et al. Circumstances of witnessed drug overdose in New York City: implications for intervention. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79:181–90. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lagu T, Anderson BJ, Stein M. Overdoses among friends: Drug users are willing to administer naloxone to others. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;30:129–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riley D, O'Hare P. Harm reduction: history, definition, and practice. In: Inciardi JA, Harrison LD, editors. Harm reduction: national and international perspectives. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2000. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Markham Piper T, Rudenstine S, Stancliff S, Sherman S, Nandi V, Clear A, et al. Overdose prevention for injection drug users: lessons learned from naloxone training and distribution programs in New York City. Harm Reduct J. 2007;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute. Harm Reduction Initiative. [cited 2007 Jan 27]. Available from: URL: http://www.health.state.ny.us/diseases/aids/about/prevsup.htm#harmred.

- 15.Nandi A, Galea S, Ahern J, Bucciarelli A, Vlahov D, Tardiff K. What explains the association between neighborhood-level income inequality and the risk of fatal overdose in New York City? Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:662–74. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hembree C, Galea S, Ahern J, Tracy M, Piper TM, Miller J, et al. The urban built environment and overdose mortality in New York City neighborhoods. Health Place. 2005;11:147–56. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galea S, Worthington N, Piper TM, Nandi VV, Curtis M, Rosenthal DM. Provision of naloxone to injection drug users as an overdose prevention strategy: early evidence from a pilot study in New York City. J Addic Behav. 2006;31:907–12. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.New York State Public Health Law A7162-A. An act to amend the public health law, in relation to opioid overdose prevention. [cited 2006 Dec 5]. Available from: URL: http://nysosc9.osc.state.ny.us/product/mbrdoc.nsf/0/1a165db3facebf7785257099004a17a4?OpenDocument.

- 19.New York State Public Health Law Section 3309(1), Part 80.138. Opiate overdose prevention: programs in New York State. [cited 2006 Oct 11]. Available from: URL: http://www.health.state.ny.us/diseases/aids/harm_reduction/opioidprevention/index.htm.

- 20.Candelas A. Applying national overdose prevention experience to local policy implementation. Presentation at the 6th National Harm Reduction Conference; 2006 Nov 11; Oakland, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Open Society Institute. OSI-Baltimore. Health experts hold forum on highly successful Baltimore overdose prevention program [press release]; 2005 Sep 20. [cited 2006 Nov 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.soros.org/initiatives/baltimore/news/health_20050920.

- 22.Ashton H, Hassan Z. Best evidence topic report. Intranasal naloxone in suspected opioid overdose. Emerg Med J. 2006;23:221–3. doi: 10.1136/emj.2005.034322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly AM, Kerr D, Dietze P, Patrick I, Walker T, Koutsogiannis Z. Randomised trial of intranasal versus intramuscular naloxone in prehospital treatment for suspected opioid overdose. Med J Aust. 2005;182:24–7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coffin PO, Fuller C, Vadnai L, Blaney S, Galea S, Vlahov D. Preliminary evidence of health care provider support for naloxone prescription as overdose fatality prevention strategy in New York City. J Urban Health. 2003;80:288–90. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]