During an emergency, material and physical resources are stretched thin and, often, the needs of those who most need help, namely the vulnerable populations, are left unmet. Vulnerable populations can be defined broadly to include those who are not able to access and use the standard resources offered in disaster preparedness and planning, response, and recovery. Age, class, race, poverty, language, and a host of other social, cultural, economic, and psychological factors may be relevant depending on the nature of the emergency.

In August 2005, Hurricane Katrina provided one illustration of the unique characteristics and vulnerabilities of specific populations in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. The storm most directly struck Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama, the poorest states in the country.1 Almost 5,000 children were separated from their families.2 Approximately 75% of all deaths in New Orleans, Louisiana, occurred among the elderly, who represented only 15% of the city's total population before the storm. Of nearly 240 shelters surveyed in the region, less than 30% had access to American Sign Language interpreters, leaving those who were deaf or hard of hearing with little or no access to vital information.3

In addition, nearly all of the 280 nursing homes in Louisiana remained full despite the calls for evacuation and, as a consequence, 215 of their residents died.4 Hundreds of school buses were available in New Orleans as part of the evacuation plan. Unfortunately, however, the Louisiana State Department of Transportation and Development's plans had not taken into account that hundreds of school bus drivers had already abandoned the city with their families. As a result, many of the vehicles never left the parking lot.5 The lack of public transportation out of the city created difficulties for the poor; Census data show that more than half of the poor households in New Orleans (54%) did not have a car, truck, or van in 2000.1 Those who managed to leave New Orleans had to endure many hardships, including lack of medications to treat chronic disease. The situation did not improve after the storm, as five months after Katrina, many elderly and other residents on the Gulf Coast continued to suffer from aggravated health problems, emotional strain, and psychological stress.6

This recent experience illustrates the need for improvements in public health planning, response, and recovery. Among other initiatives, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) established academic Centers for Public Health Preparedness (CPHP) in 2000 to assess and train the public health and health-care workforce to better respond to threats to our nation's health, including the threat of bioterrorism, infectious disease outbreak, and other public health emergencies. In addition, CDC and Association of Schools of Public Health (ASPH) established a nationwide network of CPHP to foster information sharing and reduce duplication among existing and future training and educational resources. “Collaboration groups”—workgroups of CPHP experts and key practice partners staffed by ASPH—were created in 2004 to address training issues in various topics of preparedness. Consequently, the ASPH/CDC Preparedness Education for Vulnerable Populations Collaboration Group focused in 2005–2006 on the challenges of meeting the needs of vulnerable populations—also referred to as high-risk, at-risk, special, or special-needs populations—before, during, and after a public health emergency. These vulnerable populations have needs that are not fully addressed by traditional emergency preparedness plans and may require additional resources and special attention during and after emergencies or disasters.7

Initially, the collaboration group conducted an extensive survey of available emergency preparedness training resources for public health that focused on specific vulnerable populations. Upon completion of this survey, the resources were organized into a grid, which was subsequently used to identify gaps. The purpose of this article is to describe gaps in resources related to selected vulnerable populations to inform CPHP, public health agencies, and other organizations involved in preparedness-related planning, training, and course development. For both documents, see http://www.asph.org/cphp/CPHP_ResourceReport.cfm

FINDINGS

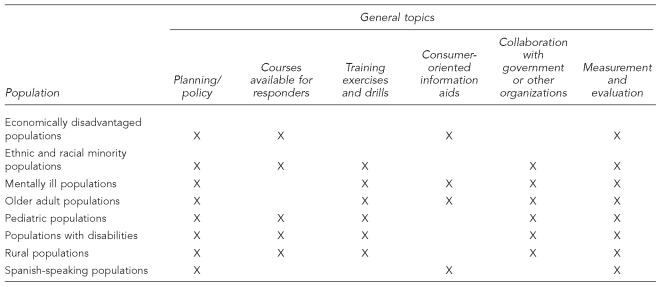

Upon review of gaps across populations, some general themes emerged, which may be categorized under six areas: (1) policy and planning, (2) responder-targeted courses, (3) training exercises and drills, (4) consumer-oriented aids and resources for the special population, (5) collaborative efforts, and (6) measurement and evaluation. Each area is described in more detail in the following sections. The Figure provides an overview of the gaps noted in each population. While these recommendations are not comprehensive, they provide an initial framework for resource development and curriculum design to train the public health workforce to meet the needs of vulnerable populations during an emergency.

Figure.

Training gaps in specific populations and areas to address these needs

NOTE: X indicates a noted gap by general topic area.

Policy/planning gaps

Despite the overarching recommendation found in various policy documents to include special populations in the planning process, few educational and training resources provide tips or guidelines on how to include vulnerable populations at the planning stage. Concrete proposals, including best practices or case studies, could be useful. Specific plans for noninstitutionalized, home-bound older adult populations were not addressed in the resources. Inclusion of needs of children (e.g., specific equipment requirements, surge capacity planning, family reunification plans, etc.) is limited in many planning and policy resources. For ethnic, racial minority, and economically disadvantaged populations, evidence-based practice as to how to engage these communities in the planning process is limited.

There is little evidence to suggest that available resources are sufficient to actively involve disadvantaged groups in planning because of limited understanding of the culture of poverty and its impact on preparedness. In each of the vulnerable populations targeted by the collaborative group, there was a paucity of policy and planning resources.

Responder-targeted courses/training

Although a number of courses available through the CPHP have modules that address the importance of vulnerable populations, few courses deal exclusively with the needs of vulnerable populations. Preparedness courses that focus specifically on the needs of populations with disabilities were not available. Some courses were found that addressed the specific needs of rural or pediatric populations. A comprehensive course on cultural competency in the context of emergencies is available. However, the consideration of cultural competence along the continuum of prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery deserves more attention. There is a clear need for more training related to cultural competence to better serve the needs of ethnic and racial minorities. In summary, more courses that focus on preparedness-related information specific to vulnerable populations, such as people with disabilities, economically disadvantaged, ethnic and racial minorities, pediatric, and rural populations, are needed.

Training exercises and drills

Members of the group highlighted the need for different types of courses that are tailored to the learning objectives and the skill level of public health practitioners. The collaboration group highlighted the lack of intermediate and advanced courses needed to address application and practice. Inclusion of the needs and issues of special populations in drills and exercises are of paramount importance in a comprehensive training curriculum. A vulnerable population component is a part of some of the drills and exercises that are currently available through the CPHP network; however, there is an urgent need for more drills and exercises that address the needs of vulnerable populations. Also required are exercises that cover issues related to vulnerable populations across the planning, response, and recovery spectrum.

Consumer-oriented aids and resources for vulnerable populations

The comprehensive matrix created by the collaboration group consists of a vast number of consumer-oriented information aids and resources, which are primarily disseminated through the Internet. The majority of these resources cannot be easily accessed by vulnerable populations, which may not have access to the Internet. For economically disadvantaged populations, there is a need for resources that are sensitive to the working poor and those who are struggling to meet daily survival needs. As apparent during Hurricane Katrina, understanding poverty is imperative. Resources that are sensitive to the needs of daily survival within the context of preparedness are needed.

For mentally ill populations, resources that prepare consumers and caregivers to be able to obtain necessary medications during and in the aftermath of a disaster are essential. Also required are resources that account for the low literacy among the mentally ill and some of their caregivers.

Checklists that focus on older adult populations are available on the Internet. However, a significant proportion of the older adult audience may not have access to the Internet or may not be able to follow detailed instructions. Also, Spanish-language resources are available on the Internet. Members of the group suggested that preparedness materials with illustrations and pictorial presentations that target Spanish-speaking populations would fill a gap. Such pictorial representations may be effective in reaching a diverse population of Spanish-speaking people, with different levels of literacy and differences in Spanish language across countries and regions of origin.

Collaboration

Guidelines on how to foster collaboration among agencies and organizations that serve vulnerable populations are insufficient. For populations with disabilities, communication gaps were identified among national agencies and organizations and nongovernmental organizations, which serve people with disabilities on a day-to-day basis. A similar gap was recognized for the mentally ill populations, specifically with the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the American Psychological Association. Committee members recognized that community- and faith-based organizations could play an instrumental role in the development of plans and the crafting of pre-event messages. One lesson learned in 2005 from Hurricane Katrina is that community groups, such as Rotary Club, faith-based organizations, and even local business owners are valuable assets in community responsiveness and recovery, particularly among rural populations. Collaboration and communication are critical pieces of the emergency preparedness, response, and recovery infrastructure and, consequently, play a pivotal role in meeting the needs of the vulnerable populations.

Measurement and evaluation

Standard metrics for the measurement and evaluation of successful training that addresses the needs of vulnerable populations are not widely discussed in the current resources. Specifically, there is no consensus measure of organizational and individual cultural competence. In the absence of established measures, it is difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of the training. For mentally ill populations, measures of post-disaster functioning of the individual and the system of care are limited. As trainings specifically related to vulnerable populations are increased and improved, evaluative measures for the individuals within the populations, the responders, and the system will have to be developed to provide a more comprehensive assessment of the preparedness, response, and recovery of vulnerable populations.

CONCLUSIONS

Improving preparedness for and response to public health emergencies will take the informed and combined effort of many people and organizations. Although government officials and agencies have an important role to play, preparedness is not solely a government responsibility. Individual citizens and families will continue to play a central role and organized efforts by both government and nongovernmental agencies must be directed to encourage and facilitate informal community-based neighbor-helping-neighbor activities. Nonprofit organizations, including local faith-based and community-based organizations, will be critical to successfully identifying, reaching, and protecting our most vulnerable citizens. The longstanding U.S. network of advocacy, service, and faith-based organizations can be effectively utilized. The development of successful education, training, and informational resources is critical to involving all of these organizations and individuals.

The work described previously by the 2005–2006 ASPH/CDC Preparedness Education for Vulnerable Populations Collaboration Group produced specific guidance for CPHP, as well as other organizations involved in preparedness-related planning, training, and course development. First, public health preparedness, response, and recovery strategies and activities should include a strong focus on the needs of specific vulnerable populations. Second, care should be taken in defining vulnerable populations and their specific needs. For example, during an emergency or disaster, the mental health or psychosocial needs of the general population may be very different from the needs of mentally ill populations. Finally, evaluation efforts for emergency preparedness training in general and measures relevant to vulnerable populations in particular should be strengthened to ensure evidence-based guidance. Inclusion of these resources related to vulnerable populations in additional training agendas is an immediate need. It should be noted that the collaboration group is continuing its work, and the needs of additional vulnerable populations will be addressed in fiscal year 2007.

Acknowledgments

Many people and organizations joined forces to produce this resource, including the Division of State and Local Readiness at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Coordinating Office for Terrorism Preparedness and Emergency Response staff, ASPH staff, and the following ASPH/CDC Preparedness Education for Vulnerable Populations Collaboration Group members (while members may have multiple affiliations, their relevant Centers for Public Health Preparedness [CPHP] affiliation is the one listed): Dr. Paul Campbell, Harvard School of Public Health, Harvard Center for Public Health Preparedness; Dr. Dan Barnett, The Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, The Johns Hopkins Center for Public Health Preparedness; Dr. Mark A. Brandenburg, University of Oklahoma College of Public Health, Southwest Center for Public Health Preparedness; Dr. Joe Coulter, University of Iowa College of Public Health, Upper Midwest Center for Public Health Preparedness; Dr. Prabu David, Ohio State University School of Public Health, Ohio Center for Public Health Preparedness; Dr. Zelde Espinel, University of Miami, Center for Hispanic Disaster Training, Center for Disaster Epidemiology; Joshua Frances, Harvard University School of Public Health, Harvard Center for Public Health Preparedness; Dr. Lynn Goldman, The Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, The Johns Hopkins Center for Public Health Preparedness; Ana-Marie Jones, University of California at Berkeley School of Public Health, Berkeley Center for Infectious Disease Preparedness; Dr. Michael Meit, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh Center for Public Health Preparedness; Gilbert Nick, Harvard University School of Public Health, Harvard Center for Public Health Preparedness; Emily C. Perry, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ) School of Public Health, New Jersey Center for Public Health Preparedness at UMDNJ; Dr. Robert Roush, University of Texas School of Public Health, Center for Biosecurity and Public Health Preparedness; Dr. Randy Rowel, Morgan State University and The Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, The Johns Hopkins Center for Public Health Preparedness; Dr. Jim Shultz, University of Miami, Center for Hispanic Disaster Training, Center for Disaster Epidemiology; and, Dr. Martha Wingate, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Public Health, South Central Center for Public Health Preparedness.

In addition, the following external reviewers provided helpful guidance on final drafts of the group's resource grid: Dick Bohrer and Robert Kidney from the National Association of Community Health Centers; Jennifer Nieratko and colleagues at the Association of State and Territorial Health Officers; and Dr. George Mensah and colleagues at CDC's National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sherman A, Shapiro I. Essential facts about the victims of Hurricane Katrina, Global Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. First published on the CGPP website on 2005 Sep 19. [cited 2006 Dec 13]. Available from: URL: www.cbpp.org/9-19-05pov.htm.

- 2.National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. Last of unaccompanied children in Katrina shelters reunited with families [press release] 2005. Oct 10, [cited 2006 Dec 19]. Available from: URL: http://www.ncmec.org/missingkids/servlet/NewsEventServlet?LanguageCountry=en_US&PageId=2150.

- 3.National Organization on Disability. Report on Special Needs Assessment for Katrina Evacuees (SNAKE) project. [cited 2006 Dec 19]. Available from: URL: http://www.nod.org/Resources/PDFs/katrina_snake_report.pdf.

- 4.Quigley B. Six months after Katrina: who was left behind Global Action on Aging, New York. Based on article in CommonDreams.org. 2006. Feb 21, [cited 2006 Oct 2]. Available from: URL: www.globalaging.org.

- 5.Spenser S. Pre-Katrina emergency plan for elderly faulted. Global Action on Aging, New York. Based on article in the Washington Post. 2006. Jan 31, [cited 2006 Oct 2]. Available from: URL: www.globalaging.org.

- 6.Leifer R. “It has disrupted my entire life.” Global Action on Aging, New York. Based on article in the Hattiesburg American. 2006. Feb 2, [cited 2006 Oct 2]. Available from: URL: www.globalaging.org.

- 7.McGough M, Frank LL, Tipton S, Tinker TL, Vaughan E. Communicating the risks of bioterrorism and other emergencies in a diverse society: a case study of special populations in North Dakota. Biosecur Bioterror. 2005;3:235–45. doi: 10.1089/bsp.2005.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]