Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and impact of an elective service-learning course offered in cooperation with a charitable pharmacy providing services to the surrounding community.

Methods

The 33 students enrolled in the service-learning elective were given a 23-question preservice survey instrument and a 32-question postservice survey instrument. The survey instruments were designed to measure change in the students’ perceived knowledge and understanding regarding civic, cultural, and social issues and health disparities.

Results

Significant differences in responses on the presurvey and postsurvey instruments suggested changes in students’ attitudes and perceptions about the patients and the community in which they serve.

Conclusions

Results of the survey indicated that by exposing students to issues affecting individuals and the community during this elective, a positive change in the student's perception of their knowledge and understanding of broader issues facing the community was observed. Service-Learning courses provide additional opportunities for students to develop as competent, engaged, and caring health care professionals.

Keywords: service-learning, civic involvement, cultural issues, social issues, health disparities

INTRODUCTION

In addition to assuring pharmacy students’ competency in the scientific and technical aspects of practice, pharmacy education should also educate students to serve society as caring, ethical professionals and enlightened citizens.1 As described in the 2004-05 Argus Commission Report, one approach to achieve this goal is to form meaningful partnerships with the community. Community engagement allows students to learn about cultural diversity, values, ethics, and leadership, while addressing and solving challenges faced by the community. Service-learning (SL) is one method of community engagement used to prepare students to become competent professionals, medication use specialists, and contribute significantly to the health of society in one or more meaningful roles.2

Service-learning is defined as a method in which students learn and develop through thoughtfully organized service that is conducted in and meets the needs of the community; is coordinated with an institution of higher education and with the community; helps foster civic responsibility; is integrated into and enhances the academic curriculum of the enrolled students; and includes structured times for students to reflect on the service experience.2 Benefits of service-learning include building critical thinking capacities, becoming lifelong learners and participants in the world, reducing stereotyping and allowing for better cultural understanding, developing interpersonal skills, citizenship, and social responsibility.3

A variety of higher education institutions offer service-learning courses. As of 2003, Campus Compact reports that 1.7 million students from 924 different colleges and universities participate in service-learning activities.4 Health profession schools, including nursing, medicine, and allied health, see the value in community engagement through service-learning. Community-Campus Partnerships for Health (CCHP) is a network of over 1000 communities and multiple health profession programs employing service-learning and other collaborative partnerships to improve the health of the community.5 Twenty-eight colleges of pharmacy offered either a voluntary or required service-learning course as of 2003.6

This paper describes an elective service-learning course designed and implemented at The University of Cincinnati College of Pharmacy. This course engages students with the community to impact their perceptions of broader issues facing the population served including civic, cultural, and social issues, as well as health disparities.

DESIGN

Service-Learning was incorporated into a required first-professional year course entitled Longitudinal Patient Care. This course focuses on a variety of topics affecting the profession such as: integration of science into patient care, communication skills, professionalism, empathy, and civic responsibility. The success of this course in introducing the concept and benefits of service-learning led to the development of the service-learning elective. In addition, a mini-grant from The Center for Healthy Communities provided funding for the purchase of blood pressure cuffs, stethoscopes, a digital weight scale, and patient education materials for the community organization, St. Vincent de Paul Community Pharmacy (SVPCP). Located at Wright State University, The Center for Healthy Communities provides funds for service-learning efforts in the health profession schools in the Midwest.

The elective service-learning course, approved by the Curriculum and Assessment Committee in the spring of 2003, is available to any student in the College upon completion of all first-professional year required courses. It is offered in all 3 academic quarters for 1 to 3 hours of credit. Prior to course registration, students must first meet with the instructor to review course requirements, which follow the 4 elements of service learning: enhancement of academic curriculum, reflective exercises, involvement of a community organization, and fostering civic responsibility.7 The course description, which follows, explains how each of the 4 elements of service-learning is integrated into the course.

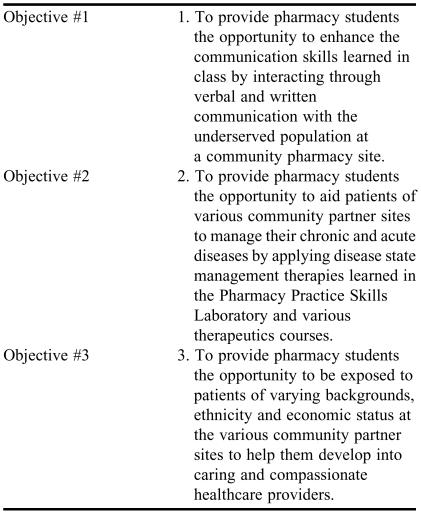

Two distinct sets of learning objectives relate the service performed to the academics. The first set includes general objectives written by faculty members (see Table 1). The second set contains 4 student-written individual learning objectives approved by the course director prior to the start of the service. These learning objectives contain 4 parts: identification of the learner, what learning is going to occur, the population being served, and the need that will be met as a result of the service. Writing personal learning objectives provides an opportunity for the student to reflect on his/her current skill set and determine which skill or skills need further development. This fulfills the first 2 parts of the individual learning objectives: learner and learning. Students also learn about the community in which they are serving and the need they are fulfilling during their experience, thereby completing the last 2 parts of the individual learning objective: population served and need.

Table 1.

Faculty Members’ Objectives for a Service-Learning Elective to Promote Enhanced Understanding of Civic, Cultural, and Social Issues and Health Disparities in Pharmacy

Another important component of the service-learning experience is reflection. Reflection is the process of internally examining and exploring an issue of concern, triggered by an experience that creates and clarifies meaning for the learner and results in a changed conceptual perspective.8 A total of 4 reflective exercises are woven into the course using both written and verbal forms of reflection. Students maintain a reflective journal using objective and subjective descriptions of activities from each service experience. At the midpoint of their service experience, students complete a written report containing the following: detailed information about the community organization and population served, a review of individual learning objectives, success to date in fulfilling the objectives, and memorable experiences. The third reflective exercise occurs at the end of the service experience. The student prepares a formal PowerPoint presentation for the instructor, community partner, and other students enrolled in the course. The presentation includes information from the midpoint written report and detailed descriptions of activities and personal reflective statements. The final written assignment is a required paper that relates a current health care issue to the activities of the community organization.

St. Vincent de Paul Community Pharmacy is a charitable pharmacy established in April 2002. It is the second of 3 charitable pharmacies in the state of Kentucky. A charitable pharmacy is one in which patients who qualify are eligible to receive their medications at no cost. The pharmacy provides care to residents of Northern Kentucky and surrounding counties which includes Campbell, Grant, Carroll, Pendelton, Gallatin, and Owen. To date, the pharmacy has filled over 80,000 prescriptions for needy residents with a retail value of over 5 million dollars. As stated by one of the founders, the focus is on those who “fall through the cracks” of the current health care system.9 Most of the patients are uninsured, elderly, mentally ill, or low-income patients who would otherwise be unable to afford their medications.

Students complete 20 to 60 hours of service at St. Vincent de Paul Community Pharmacy, depending on the number of credit hours selected. Students performed a variety of pharmacy-related activities such as filling prescriptions, counseling patients, taking medication histories, and collaborating with other health care providers. Students also participated in 2 unique activities not found in a traditional pharmacy: qualification of patients for assistance and community outreach. Qualification of a patient for the program involves the students performing a detailed individual, financial, and personal interview. In order for patients to qualify, they must have limited income sources and no viable health insurance coverage. The outreach program provides pharmacy services to qualified patients living in primarily rural areas. This weekly program involves pharmacy personnel, including students traveling to those communities. They deliver medications, provide patient education, and perform qualifying interviews for those physically unable to reach the charitable pharmacy. By seeing patients in their own environment, students’ opinions change regarding civic, cultural, and social issues, and the health disparities found in the community.10

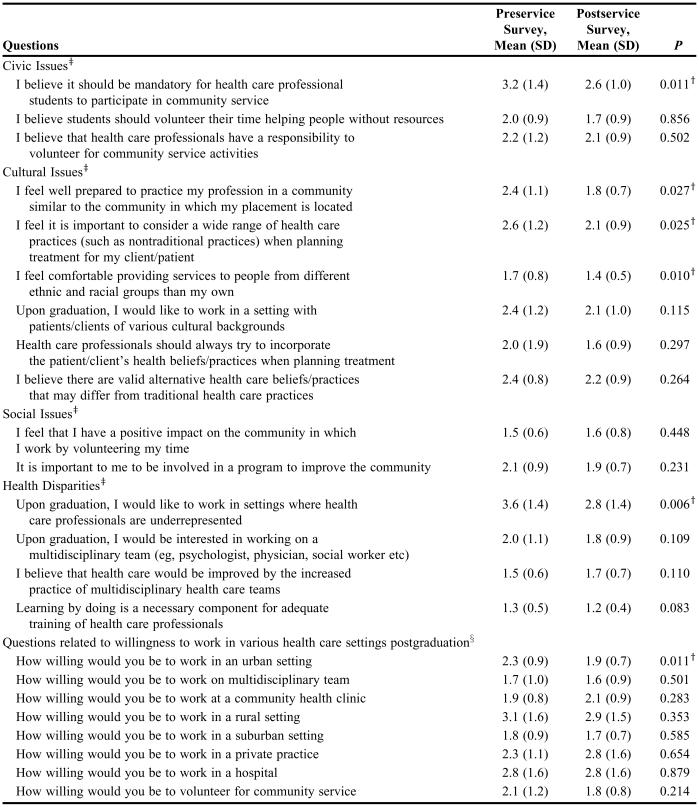

In order to assess the impact on students’ civic, cultural, and social awareness, we administered optional, anonymous preservice and postservice questionnaires. To allow for paired data analysis, students volunteering to complete the survey instrument chose a unique identifier that was used on both survey instruments so that individual comparisons between pre- and postservice responses could be made. The survey instrument was designed by the Center for Healthy Communities, Wright State University, and administered with permission (Table 2 and 3). This survey tool consists of questions regarding demographic data, previous work history, volunteer experience, 15 questions regarding civic, cultural, and social issues, and 8 questions regarding post-graduation work placement. All 15 questions related to civic, cultural, and social issues were answered using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly agree and 7 = strongly disagree). Students also used a 7-point Likert scale (1 = very willing, 7 = very unwilling) to respond to the remaining 8 work-related questions.

Table 2.

Results of Preservice and Postservice Survey of Pharmacy Students Completing a Service-Learning Experience at a Community Pharmacy*

*Assessed using the Center for Healthy Communities Student Survey Instrument

†Indicates significant P value <0.05

‡Seven-point Likert scale used: 1 = strongly agree to 7 = strongly disagree

§Seven-point Likert scale used: 1 = very willing to 7= very unwilling

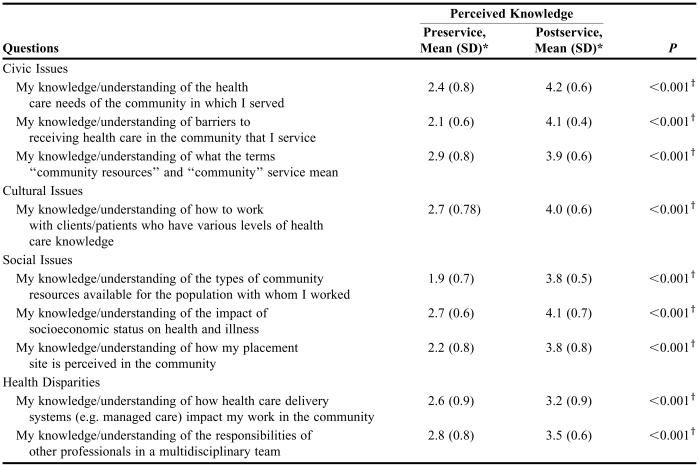

Table 3.

Results of a Retrospective Preservice-Postservice Survey of Pharmacy Students Completing a Service-Learning Experience at a Community Pharmacy

Assessed using the Center for Healthy Communities Student Survey Instrument

*Five-point Likert scale used: 1= No knowledge or understanding to 5 = Extensive Knowledge or Understanding

†Indicates p value < 0.05

The postservice survey instrument consisted of the same 23 questions found in the preservice survey instrument, along with 9 additional questions (see Table 3). These questions, which addressed the broader issues faced by the community served, are designed as retrospective pre/post questions. This type of question allowed students to simultaneously reflect on their perceived knowledge before and after the service-learning experience. A 5-point Likert scale (1 = no knowledge or understanding, 5 = extensive knowledge or understanding) was utilized for this group of questions as this scale more readily shows perceived changes in knowledge or understanding compared to a 7-point Likert scale.

For example, a question from the post-service survey reads: “My knowledge or understanding of the health care needs of the community in which I served.” Students indicate their perceived knowledge about the subject content both before service and after service. This type of concurrent questioning indicates a more accurate assessment of changes in the students’ perceived understanding, thus avoiding response-shift bias.11 Paired t tests were used to compare the preservice and postservice survey instruments (SPSS, version 13.0, Chicago, Ill.)

RESULTS

Thirty-three students completed the course from spring 2003 (when it was first offered) to fall 2005. All students completed both survey instruments and all results were included for analysis. Significant differences were found between preservice and postservice responses to 6 of 23 statements (Table 2). Three of the statements covered cultural issues, 1 statement reflected the student's opinions regarding health disparities, and 1 statement reflected a change in attitude of possible postgraduation employment. Significant differences also were identified in the concurrent responses to all 9 perceived knowledge questions included only on the postservice survey instrument (Table 3). These included 3 questions relating to civic issues, 1 question on cultural issues, 3 questions on social issues, and 2 on health disparities.

The reflective writings, which were required in the course, also showed that the service experience impacted the student's perceived understanding of civic, cultural, and social issues. One student wrote the following entry in his reflective journal: “…It was a good experience for me to learn what it is like to be the one who was different.” Another statement that expresses the perceived benefits of service learning: “As I reflected on each visit, I realized that not only did I help others, I helped myself.” A final statement revealed insight regarding the ability to provide culturally competent care: “I have learned not to judge others that seek help. They realize that they cannot do it on their own…”

DISCUSSION

Survey results and anecdotal reports indicate a change in the students’ perceptions toward providing care to a diverse population and possibly to changes in postgraduation employment plans. Student attitudes related to cultural issues also changed. Students felt more prepared to practice in a community similar to the service-learning site. Also, they perceived an improved ability to consider complimentary/alternative medical practices when caring for a patient. These results are similar to those found by Barner who stated that after completing a required service-learning course, students reported feeling more comfortable providing services to patients with a culturally different background than their own.12 Jarvis et al found similar results in which pharmacy students reported that through a service-learning course, they increased their appreciation for different cultures and socioeconomic groups, while making a valuable contribution to the community.13 This change in perception is an indication of student's progress in becoming a culturally competent health care provider. The survey also revealed that students became more aware of civic issues. Those who participated in this elective felt strongly that “community service should be mandatory for all health profession students.” Kearney found similar results from surveying students prior to and after a service-learning course in which the students were generally open to service-learning experiences.14 These results, however, differ from what was found in a study by Piper et al in which approximately 20% of the students completing a required service-learning course thought the course should be removed from the curriculum.15

One of the 6 questions included on both the preservice and postservice survey instruments, indicated a significant change as related to perceived knowledge of existing health disparities. A statement such as “Upon graduation, I would like to work in settings where health care professionals are underrepresented” indicated the student's realization of the disparity in health care services by entertaining the possibility of seeking employment in underserved areas. Regarding postgraduation employment plans, there was a significant change in the students’ willingness to work in urban settings The community partner, St. Vincent de Paul Community Pharmacy, is located in a metropolitan area of Northern Kentucky and primarily serves patients that live in this urban setting. This may be one reason for students’ changed attitudes toward this type of health care setting.

All 9 questions found only on the postservice survey instrument revealed a significant change in the student's perception of their knowledge about civic, cultural, and social issues before and after the experience. By allowing the student to become actively involved with the population served, they realized that their prior knowledge about issues related to their patients’ problems and concerns may have been unrealistic or lacking (Table 3). Such statements as “My knowledge/understanding of the barriers to receiving health care in the community I serve,” as well as “My knowledge/understanding of the health care needs of the community in which I served,” show the effects of service-learning on the students’ understanding of civic issues. The most significant changes in perceived knowledge or understanding of the patient population served occurred in the statements regarding social issues (Table 2). These statements: “My knowledge or understanding of the community resources available and impact of socioeconomic status on health and illness” are enlightening. By interacting with patients who are experiencing difficulties with health and health care, students are exposed to real life issues faced by patients on a daily basis. These results are similar to the results found with graduate nursing students by Narsavage et al.16 In our opinion, talking about social issues in the classroom is beneficial; however, experiencing those issues in a real life setting can have a greater impact on the students’ perceived understanding.

This study had several limitations. The course was an elective offered immediately following the completion of required service-learning activities. Students who elected to participate were most likely students who realized the benefit of such courses and this self-selection for participation may have biased the results and led to more favorable responses on the survey instruments. As noted by Piper et al, students with prior community service experience have a significantly greater change in their responses to survey questions than students who have no prior experience.15 These students are also more motivated. Service-learning courses are active-learning experiences, placing the burden of learning on the student. This too, may have biased the results of the survey. One additional limitation was the subjectivity of the assessment. The students assessed their own perceived knowledge regarding broad social issues.

CONCLUSION

Health professions educators must face the task of educating students to become competent in the sciences while preparing them to become engaged citizens willing to tackle disparities in our health care system.17 Service-learning is one method of engaging students in active learning to promote awareness of civic, cultural, and social issues faced by the patients they serve. Other health professions successfully use this andragogical approach. As noted in the nursing literature, service-learning sends a powerful message about the value of volunteerism and the need to make progress on one's cultural competence journey.18 In the medical literature it is noted that service-learning courses have emerged to strengthen the relationships between academic medicine and community health.19 At The University of Cincinnati College of Pharmacy, service-learning is integrated into both the required and elective curriculum to provide opportunities for student growth. Service-learning is one teaching strategy that can be used enhance the professional development of health professions students. As noted by The American Pharmaceutical Association 1994 code of ethics, a pharmacist “serves individual, community and societal needs,” as well as “seeks justice in the distribution of health resources.”20 Exposing students to issues affecting individuals, health profession educators provide additional opportunities for professional growth by increasing the students’ knowledge of social, cultural, and civic issues, as well as health disparities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Rosanna Aydt, cofounder of the St. Vincent de Paul Community Pharmacy, for her work and commitment to providing a unique educational opportunity for pharmacy students and a greatly needed service to the community.

REFERENCES

- 1. AACP Commission to Implement Change in Pharmaceutical Education. What is the Mission of Pharmaceutical Education. Available at: http://www.aacp.org/Docs/MainNavigation/EducationalResources/3586_BackgroundPaper1.pdf Accessed January 16, 2006.

- 2. Engaging Communities: Academic Pharmacy Addressing Unmet Public Health Needs. Report of the 2004-05 Argus Commission. Available at: http://www.aacp.org/Docs/AACPFunctions/Governance/6822_2005ArgusreportEngagingCommunities.doc?DocTypeID=4&TrackID=www.aacp.org/search/search.asp?qu=Arg Accessed January 16, 2006.

- 3.Eyler J, Giles DE. Where's the Learning in Service Learning. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Campus Compact. Available at: http//www.campuscompact.org. Accessed January 17, 2006.

- 5. Community-Campus Partnerships for Health. Available at: http://depts.washington.edu/ccph/servicelearningres.html. Accessed January 31, 2006.

- 6.Peters SJ, MacKinnon GE. Introductory practice and service learning experiences in US Pharmacy Curricula. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(1) Article 27. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter JT, Cochran GA. Service learning projects in a public health in pharmacy course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2002;66:312–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navtivio DG. Advanced practice, service-learning, the scholarship of service. Nurs Outlook. 2001 Jul–Aug;49:164–5. doi: 10.1067/mno.2001.117770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McCullough A. Plans seeks free prescriptions for needy. The Enquirer [online edition]April 24, 2004. Available at: http://www.enquirer.com/editions/2004/04/24/loc_freedrugs24.html. Accessed January 17, 2006.

- 10.Ottenritter NW. Service learning, social justice and campus health. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;52:189–91. doi: 10.3200/JACH.52.4.189-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pratt CC, McGuigan WM, Katsev AR. Measuring program outcomes: using retrospective pretest methodology. Am J Eval. 2000;21:341–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barner JC. First-Year pharmacy students’ perceptions of their service-learning experience. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64:266–71. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jarvis C, James V, Giles J, Turner C. Nutrition and nurturing: A service-learning nutrition pharmacy course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68 Article 43. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kearney K. Students’ self-assessment of learning through service-learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68 Article 29. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piper B, DeYoung M, Langsam GD. Student perceptions of a service-learning experience. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64:159–65. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Narsavage GL, Lindell D, Chen YJ, et al. A community engagement initiative: service-learning in graduate nursing education. J Nurs Educ. 2002;41(10):457–61. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20021001-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Redman RW, Clark L. Service-learning as a model for integrating social justice in the nursing curriculum. J Nurs Educ. 2002;41(10):446–8. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20021001-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Worrell-Carlisle P. Service-learning: a tool for developing cultural awareness. Nurs Educ. 2005;30(5):197–202. doi: 10.1097/00006223-200509000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elam CL, Sauer MJ, Stratton TD. Service learning in the medical curriculum: developing and evaluating an elective experience. Teach Learn Med. 2003;15(3):194–203. doi: 10.1207/S15328015TLM1503_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. American Pharmaceutical Association. Available at: http://www.aphanet.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Search&template=/CM/HTMLDisplay.cfm&ContentID=2809. Accessed January 31, 2006.