Abstract

SUMMARY

Purpose

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer related mortality in the world. BAC is a subset of NSCLC that has recently gained attention because of distinct biologic and clinical features, increased incidence, and enhanced responsiveness to new therapies such as epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs). However, prognostic features for BAC have not been well defined. Because activation of Akt is highly prevalent and a poor prognostic factor for other types of NSCLC, we assessed the prognostic significance of clinical features and Akt activation in patients with BAC.

Methods

46 cases of BAC in Iceland were classified according to WHO 1999 criteria. Akt activation was assessed using two phospho-specific antibodies against Akt (S473 and T308) in immunohistochemical analysis. Associations between ordered Akt levels and other dichotomous parameters were evaluated using an exact Cochran-Armitage test for trend. Survival was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test, with hazard ratios (HR) determined by Cox proportional hazard models. The Cox model was also used to assess the joint effect of multiple factors on survival when they are considered simultaneously.

Results

Age and histology (mucinous vs. non-mucinous) were not associated with survival. Activation of Akt was highly prevalent in BAC, with only 2 out of 46 patients exhibiting negative staining with either antibody. Moderate to high Akt activation was observed in 63% of cases and was associated with non-mucinous histology. Akt activation was not associated with differences in survival or smoking status. In contrast, Cox model analysis revealed that male gender (HR 2.24, 95% CI 1.07-4.71, p=0.032), advanced stage (III or IV) (HR 2.17, 95% CI 1.004-4.71, p=0.049), and smoking status (HR 6.89, 95% CI 1.49-31.88, p=0.013) were associated with a worse prognosis.

Conclusions

Male gender, advanced stage, and especially smoking status (but not Akt activation) are potentially important prognostic features for BAC. These features should be considered in the design and interpretation of clinical trials that enroll BAC patients.

Keywords: bronchioloalveolar carcinoma, prognostic factor, NSCLC, Akt, smoking

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer mortality in the United States, and more people die from this disease than from breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer combined (1).

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) comprises 80–85% of all lung cancer cases, and is a heterogeneous category composed of various histologic subtypes. In 1999, the World Health Organization updated its classification and redefined bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC) as being restricted to noninvasive tumors. Since this reclassification, prognostic features of patients with newly defined BAC have not been well defined, in spite of the fact that the disease appears to have a distinct clinical course and response to treatment (2, 3). Although typically resistant to traditional chemotherapies, BAC is highly sensitive to EGFR-TKIs such as erlotinib and gefitinib. Other features that are associated with increased sensitivity to EGFR-TKIs such as female gender, never smokers, and Asian ethnicity, are also disproportionately associated with BAC histology (4–7).

Preclinical studies from our group have suggested that activation of the serine/threonine kinase Akt plays an important role in the formation, maintenance, and therapeutic resistance of lung cancer (8–12). Although we recently reported that Akt activation, as defined by staining for two activation-state specific antibodies in immunohistochemical analysis, confers a poor prognosis for NSCLC patients with squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma (13), the prognostic value of Akt activation in patients with BAC is unknown. Since the biologic properties and clinical course of patients with BAC may be distinct from other subtypes of NSCLC, we conducted a study to investigate the prognostic significance of clinicopathological factors and Akt activity in a cohort of BAC patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a population-based study of all patients with the diagnosis of BAC in Iceland from February 1959 until Feb 2004. All patients underwent surgery at the University Hospital of Iceland. Diagnoses were histologically verified at the Department of Pathology, University Hospital of Iceland. The cohort is intended to include all patients in Iceland with the diagnosis of BAC during this 45-year period, as the Icelandic Cancer Registry extends back to the year 1954 and is nationally based. All the specimens originally registered as BAC in the National Cancer Registry of Iceland were reviewed by pathologists according to the 1999 WHO lung tumor classification, and those who met the criteria for BAC were analyzed in the study. Information on patients, their disease, diagnosis, treatment and survival (as well as smoking habits) was obtained from hospital records. ‘Never smokers’ were those who had never smoked or smoked less than 100 cigarettes in their lifetimes, and the rest of the patients were classified as ‘smokers’. The local ethics committees approved this study. Information on survival was obtained from the Genetic Committee, University of Iceland. The longest period of follow-up for a given case was 23 years. All patients received surgery with curative intent, except for three patients, two of whom had inoperable tumors with histopathological diagnosis obtained via needle biopsy, and one whose BAC was discovered at autopsy.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining and scoring

Immunohistochemical staining and scoring was performed as described previously (13), except that primary phospho-S473 or T308 Akt antibodies were used at a 1:100 dilution. In addition, scoring only incorporated intensity because the distribution of staining was uniform.

Statistical analysis

Associations between Akt and the other categorical parameters were evaluated using an exact Cochran-Armitage test for trend (14). Associations between dichotomous parameters were evaluated for statistical significance using Fisher's exact test. The probability of survival as a function of time from date of diagnosis was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, with statistical comparisons between pairs of curves done by the log-rank test (15, 16). Hazard ratios for survival when patients were divided into two groups were determined using univariate Cox proportional hazards models (17, 18). In addition, the Cox model was used to assess the joint effect on survival when multiple factors were considered simultaneously. Backward selection was used to obtain the final model. A likelihood ratio test was also performed to assess the statistical significance of Akt when added to a model containing standard parameters, an approach described by Simon and Altman (19). All p-values are two-tailed.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the patients with BAC are shown in Table 1. Forty-six patients with histopathologically proved BAC in accordance with the WHO classification of lung tumors revised in 1999 (20) were enrolled in this study, and median age was 65 years old (range 38–84). Among 45 patients with clinical data available, women accounted for 62.2% of patients, and 60% had stage I-II diseases. Smoking status was known in 69.6% of patients, in which 9 cases were never smokers, and 23 cases were ever-smokers. Eight BAC cases were diagnosed with mucinous subtype, and 37 cases with non-mucinous subtype.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| n=46 | |

|---|---|

| Median age (range) | 65 (38-84) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 28 |

| Male | 17 |

| unknown | 1 |

| Clinical Stage | |

| I | 16 |

| II | 11 |

| III | 8 |

| IV | 9 |

| unknown | 2 |

| Smoking | |

| Never smoker | 9 |

| Smoker | 23 |

| unknown | 14 |

| Histology | |

| mucin | 8 |

| non-mucin | 37 |

| unknown | 1 |

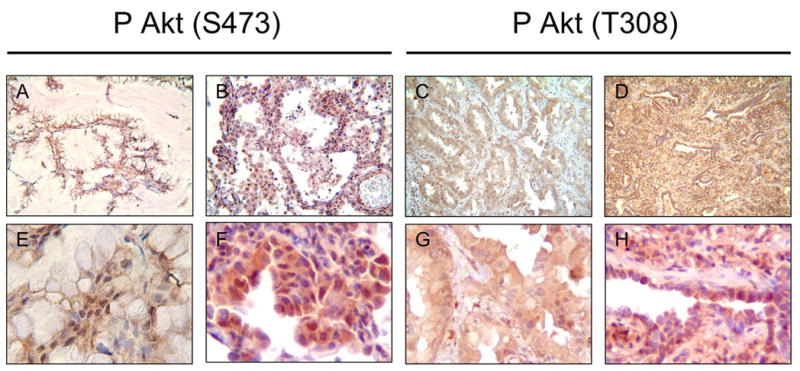

Akt activation was assessed in each patient by combining the staining intensities for phospho-S473 and phospho-T308. Representative staining with each antibody is shown in Figure 1. Tumor cells were preferentially stained and exhibited both cytoplasmic and nuclear staining. There were 13 patients (28.2%) whose tumors had high levels of Akt activation, 17 (36.9%) with intermediate levels of Akt activation, and 15 (32.6%) with low levels of Akt activation. There was no association between length of time the tissue was maintained in fixative and levels of Akt activation. For example, tumors that scored lowest in Akt activation were preserved for an average of 13.1 yr, the intermediate level group 14.7 yr, and the highest level group 16.5 yr. These differences were not statistically different (p> 0.2 for all two tailed comparisons) (data not shown). Amongst the clinicopathological features, non-mucinous histology was associated with Akt activation (P=0.026, Table 2). There were no significant associations between Akt activity and gender, smoking status, or stage (Table 2). Due to the fact that some patients were diagnosed prior to routine use of computed tomography for staging, it is possible that inaccurate staging could have contributed to the lack of association between Akt and tumor stage. However, 80.4% of patients (37/46) were followed for less than 20 yr, during which time computed tomography was routinely used for staging. There were no associations observed between gender and smoking status or stage (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical analysis with phospho-Akt antibodies in BAC specimens. Representative staining with phospho-S473 (A, B, E, F) and phopsho-T308 antibodies (C, D, G, H) is shown. (A, B, C, D 100X magnification; E, F, G, H 400X magnification ×400).

Table 2.

Association between AKT and Other Variable

| Low | Akt Med | High | Exact C-A P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 11 | 10 | 7 | 0.34 |

| Male | 4 | 7 | 6 | |

| Smoking* | ||||

| Never | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1.00 |

| Smoker | 6 | 10 | 7 | |

| Histology | ||||

| Mucin | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0.026 |

| Non-Mucin | 10 | 14 | 13 | |

| Stage | ||||

| I-II | 11 | 8 | 8 | 0.57 |

| III-IV | 4 | 8 | 5 | |

Excludes those without information available.

C-A: Cochran-Armitage

Table 3.

Gender versus Selected Clinical Variables

| Gender Male | Female | Fisher Exact P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | |||

| Never | 3 | 6 | 0.69 |

| Smoker | 11 | 12 | |

| Stage | |||

| I-II | 8 | 19 | 0.20 |

| IIIIV | 9 | 8 | |

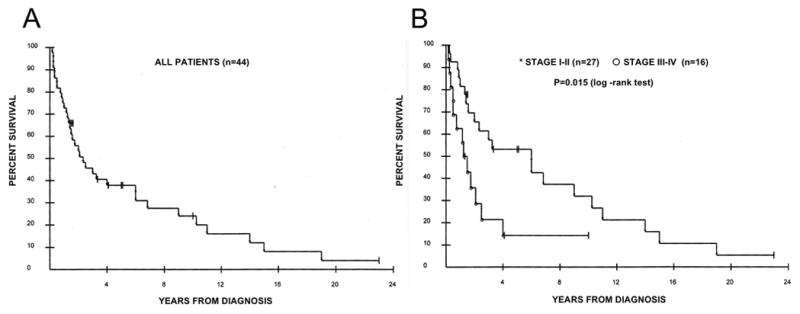

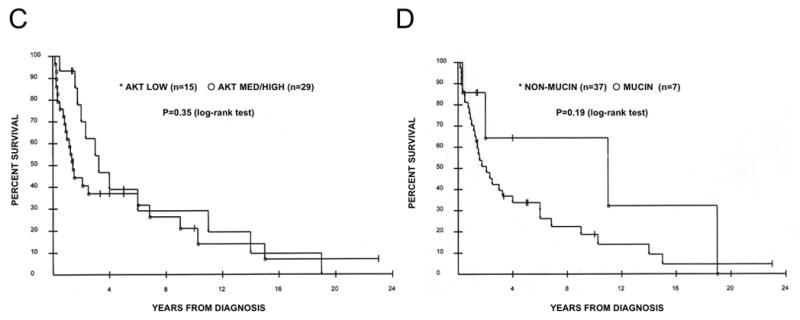

Kaplan-Meier analyses stratified by clinicopathological valuables or Akt activation are shown in Figure 2. Twelve patients were alive at the time of analysis, and no patient was lost to follow-up. The median survival time in all cases with clinical data is 2.1 years (Figure 2A), and survival probabilities were significantly greater in stage I-II, never-smoking, and female patients than in their counterparts (P=0.015, 0.0058 and 0.015 (log-rank test), respectively, in Figure 2, panels B, E and F). Although there were very slight trends that survival probabilities were somewhat greater in those whose tumor had low Akt activity, or non-mucinous subtype, the differences did not reach statistical significance (P=0.35, and 0.19, respectively in Figure 2, panels C and D).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves stratified by clinicopathological factors. (A) All patients (n=44). (B) Stratification by stage I-II (asterisks, n=27) vs. stage III-IV (open circles, n=16), p=0.015 (log-rank test). (C) Stratification by Akt status. Asterisks denote low Akt (n=15) and open circles denote med/high Akt (n=29), p=0.35 (log-rank test). (D) Stratification by mucinous histology. Asterisks denote non-mucinous type (n=37), and open circles denote mucinous type (n=7), p=0.19 (log-rank test). (E) Stratification by smoking status. Asterisks denote smokers (n=23), and open circle denote non-smokers (n=8), p=0.0058 (log-rank test). (F) Stratification by gender. Asterisks denote female patients (n=28), and open circles denote male patients (n=16), p=0.016 (log-rank test).

The results of univariate analysis regarding the association of a variety of factors with survival are summarized in Table 4. The final Cox proportional hazard model on 43 patients, excluding smoking, demonstrated that male gender and advanced stage were jointly found to be poor prognostic factors in the cohort (hazard ratios 2.24 (95% C.I. 1.07–4.71, P=0.032) and 2.17 (95% C.I. 1.004–4.71, P=0.049), respectively; see Table 5A). Smoking status was the only prognostic factor, with hazard ratio 6.89 (95% C.I. 1.49–31.88, P=0.013) in the Cox proportional hazards model based on 31 patients for whom smoking history was available (Table 5B).

Table 4.

Univariate Analysis of Association of Factors with Survival in Patients with BAC

| Trait | HR | 95% C.I. for HR | L-R P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| AKT (L vs M/H) | 1.4 | (0.69–2.82) | 0-35 |

| T308 (L vs H) | 1.06 | (0.54–2.06) | 0.87 |

| Age (<=65 vs.66+) | 1.47 | (0.74–2.91) | 0.64* |

| Gender | 2.33 | (1.14–4.77) | 0.016 |

| Stage | 2.46 | (1.16–5.21) | 0.015 |

| Mucin / Non-Mucin | 2.01 | (0.7–5.77) | 0.19 |

| Smoking | 6.89 | (1.49–31.88) | 0.0058 |

L-R: log-rank test

L: Low; M: Intermediate; H: High

global p-value based on 4 age categories.

Table 5-A.

Final Cox proportional hazard model based on 43 patients with complete data (except for smoking)

| Variable | Parameter Estimate | P-value | HR | 95%C.I.for HR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.81 | 0.032 | 2.24 | 1.07–4.71 |

| Stage | 0.77 | 0.049 | 2.17 | 1.004–4.71 |

HR: hazard ratio; C.I.: confidence interval

Table 5-B.

Final Cox proportional hazard model based on 31 patients with smoking history available

| Variable | Parameter Estimate | P-value | HR | 95%C.I.for HR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | 1.93 | 0.013 | 6.89 | 1.49–31.88 |

HR: hazard ratio; C.I.: confidence interval

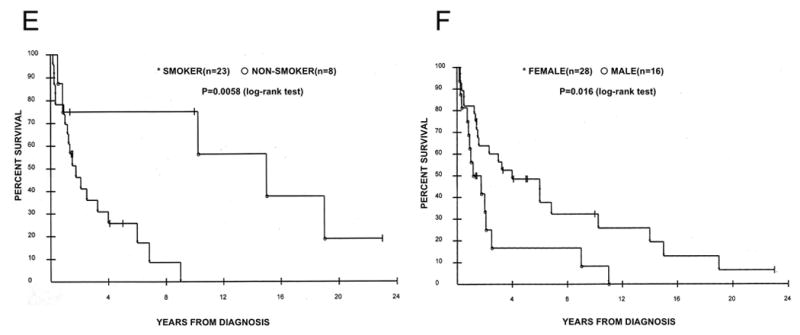

Since we previously showed that evaluation of T308 phosphorylation alone might better reflect the prognostic significance of Akt activation (especially for early stage patients) (8), Kaplan-Meier analyses were repeated and stratified by T308 phosphorylation for all patients or restricted to those with stage I-II disease (Figure 3). There were no significant differences in survival probability between those whose tumor had high or low T308 phosphorylation in all patients or restricted to those with stage I-II disease (P=0.87 and 0.73, respectively). Furthermore, there were no significant associations between phosphorylation of T308 and clinicopathological factors (data not shown). These results show that Akt activation, as defined by either combining both sites of phosphorylation or taken individually, is not prognostic for BAC patients in this cohort. In contrast, clinical features such as smoking status, male gender, and advanced stage were identified as potentially important prognostic factors.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves stratified by phosphorylation of Akt on T308 in all patients (A), and stage I-II patients (B). Asterisks denote low Akt (n=21 in all patients, n=15 in stage I-II patients), and open circles denote high Akt (n=23 in all patients, n=12 in stage I-II patients). p=0.87 and 0.73 (log-rank) in (A) and (B), respectively.

DISCUSSION

Akt is an emerging target for cancer therapy because its activation confers a poor prognosis for many tumor types (21). We previously demonstrated that Akt activation was highly prevalent and highly selective for tumor vs. normal tissues in NSCLC patients (13). In addition, we observed an inverse association between survival of patients with NSCLC and Akt activity in NSCLC tumors. In that study, 300 primary NSCLC cases (150 cases of squamous cell carcinoma and 150 cases of adenocarcinoma) were examined for phosphorylation of Akt on S473 and T308 sites using IHC in a tissue microarray system. Evaluating an additional phosphorylation site (T308) appeared to improve the prognostic value of Akt activity (13). The present study demonstrated that Akt activation is also highly prevalent in BAC specimens, which is consistent with studies by Cappuzzo et al. that showed that S473 phosphorylation was positive in 10/13 BAC patients (22). Despite the high prevalence in our current study, however, there was no association between Akt activation and the prognosis of patients with BAC. The discordant prognostic significance of Akt activation in our prior and current studies implies that the role of Akt in BAC is distinct from other histological subtypes in NSCLC. Although the biological basis for this distinction is unclear, such histological subtype-specific association of Akt activation with survival of cancer patients has been demonstrated previously in subtypes of endometrial, ovarian, and thyroid cancers (23–25).

Even though Akt activation was not associated with survival, it was associated with non-mucinous histology, which could be related to the molecular abnormalities that are characteristic of non-mucinous BAC. For example, compared to mucinous BAC, non-mucinous BAC is more commonly associated with neoangiogenesis and remodeling of extracellular matrix (26), increased expression of EGFR and erbB2 (27), and mutations in p53 (28). Akt has been linked to each of these processes, as it is required for some types of experimental angiogenesis (29), is activated by EGFR and erbB2 (30, 31), and has reciprocal regulation of p53 function (32, 33). Like Akt activation, non-mucinous histology was not associated with poor prognosis, which is consistent with an earlier study that showed that survival of BAC patients with mucinous and non-mucinous histologies was not different (34).

Irrespective of Akt activation, we observed that gender, stage and smoking status were associated with the probability of survival in patients with BAC. There were no significant associations between these variables, and gender and smoking status were each found to be prognostic factors in this cohort. Advanced stage and increased tumor size have been previously reported as poor prognostic factors for patients with BAC (34, 35). However, the strong impact of smoking in survival of patients with BAC has not been reported previously. These results are consistent with the impact of smoking in other forms of NSCLC, and strengthen the concept that NSCLC is truly different in smokers vs. non-smokers.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: None declared for all authors

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, Samuels A, Tiwari RC, Ghafoor A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2005. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005 Jan–Feb;55(1):10–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scagliotti GV, Smit E, Bosquee L, O'Brien M, Ardizzoni A, Zatloukal P, et al. A phase II study of paclitaxel in advanced bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (EORTC trial 08956) Lung Cancer. 2005 Oct;50(1):91–6. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.West HL, Crowley JJ, Vance RB, Franklin WA, Livingston RB, Dakhil SR, et al. Advanced bronchioloalveolar carcinoma: a phase II trial of paclitaxel by 96-hour infusion (SWOG 9714): a Southwest Oncology Group study. Ann Oncol. 2005 Jul;16(7):1076–80. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukuoka M, Yano S, Giaccone G, Tamura T, Nakagawa K, Douillard JY, et al. Multi-institutional randomized phase II trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (The IDEAL 1 Trial) [corrected] J Clin Oncol. 2003 Jun 15;21(12):2237–46. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, Tan EH, Hirsh V, Thongprasert S, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005 Jul 14;353(2):123–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kris MG, Natale RB, Herbst RS, Lynch TJ, Jr, Prager D, Belani CP, et al. Efficacy of gefitinib, an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in symptomatic patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized trial. Jama. 2003 Oct 22;290(16):2149–58. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller VA, Kris MG, Shah N, Patel J, Azzoli C, Gomez J, et al. Bronchioloalveolar pathologic subtype and smoking history predict sensitivity to gefitinib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Mar 15;22(6):1103–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brognard J, Clark AS, Ni Y, Dennis PA. Akt/protein kinase b is constitutively active in non-small cell lung cancer cells and promotes cellular survival and resistance to chemotherapy and radiation. Cancer Res. 2001;61(10):3986–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.West KA, Brognard J, Clark AS, Linnoila IR, Yang X, Swain SM, et al. Rapid Akt activation by nicotine and a tobacco carcinogen modulates the phenotype of normal human airway epithelial cells. J Clin Invest. 2003 Jan;111(1):81–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI16147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.West KA, Linnoila IR, Belinsky SA, Harris CC, Dennis PA. Tobacco carcinogen-induced cellular transformation increases activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3'-kinase/Akt pathway in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2004 Jan 15;64(2):446–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsurutani J, Castillo SS, Brognard J, Granville CA, Zhang C, Gills JJ, et al. Tobacco components stimulate Akt-dependent proliferation and NF{kappa}B-dependent survival in lung cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2005 Mar 24; doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsurutani J, West KA, Sayyah J, Gills JJ, Dennis PA. Inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway but not the MEK/ERK pathway attenuates laminin-mediated small cell lung cancer cellular survival and resistance to imatinib mesylate or chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2005 Sep 15;65(18):8423–32. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsurutani J, Fukuoka J, Tsurutani H, Shih JH, Hewitt SM, Travis WD, et al. Evaluation of two phosphorylation sites improves the prognostic significance of Akt activation in non-small-cell lung cancer tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Jan 10;24(2):306–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1990. pp. 100–2. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan E, Meier P. Non-Parametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mantel N. Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consierations. Cancer Chem Rep. 1966;50:163–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox D. Regression models and life tables. J Royal Stat Soc. 1972;34(B):187–202. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matthews DE, Farewell VT. Using and understanding medical statistics. Basel: Karger; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simon R, Altman DG. Statistical aspects of prognostic factor studies in oncology. Br J Cancer. 1994 Jun;69(6):979–85. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Travis WDC, Corin T, Shimosato B, Brambilla Y, E Sobin LH. World health organization: histological typing of lung and pleural tumors. Berlin: Springer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altomare DA, Testa JR. Perturbations of the AKT signaling pathway in human cancer. Oncogene. 2005 Nov 14;24(50):7455–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cappuzzo F, Magrini E, Ceresoli GL, Bartolini S, Rossi E, Ludovini V, et al. Akt phosphorylation and gefitinib efficacy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004 Aug 4;96(15):1133–41. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ringel MD, Hayre N, Saito J, Saunier B, Schuppert F, Burch H, et al. Overexpression and overactivation of Akt in thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2001 Aug 15;61(16):6105–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mills GB, Lu Y, Fang X, Wang H, Eder A, Mao M, et al. The role of genetic abnormalities of PTEN and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway in breast and ovarian tumorigenesis, prognosis, and therapy. Semin Oncol. 2001 Oct;28(5 Suppl 16):125–41. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Risinger JI, Hayes K, Maxwell GL, Carney ME, Dodge RK, Barrett JC, et al. PTEN mutation in endometrial cancers is associated with favorable clinical and pathologic characteristics. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4(12):3005–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guedj N, Couvelard A, Arcangeli G, Dubois S, Thabut G, Leseche G, et al. Angiogenesis and extracellular matrix remodelling in bronchioloalveolar carcinomas: distinctive patterns in mucinous and non-mucinous tumours. Histopathology. 2004 Mar;44(3):251–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.01803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erman M, Grunenwald D, Penault-Llorca F, Grenier J, Besse B, Validire P, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor, HER-2/neu and related pathways in lung adenocarcinomas with bronchioloalveolar features. Lung Cancer. 2005 Mar;47(3):315–23. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marchetti A, Pellegrini S, Bertacca G, Buttitta F, Gaeta P, Carnicelli V, et al. FHIT and p53 gene abnormalities in bronchioloalveolar carcinomas. Correlations with clinicopathological data and K-ras mutations. J Pathol. 1998 Mar;184(3):240–6. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199803)184:3<240::AID-PATH20>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wen S, Stolarov J, Myers MP, Su JD, Wigler MH, Tonks NK, et al. PTEN controls tumor-induced angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(8):4622–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081063798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou BP, Hu MC, Miller SA, Yu Z, Xia W, Lin SY, et al. HER-2/neu Blocks Tumor Necrosis Factor-induced Apoptosis via the Akt/NF- kappaB Pathway. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(11):8027–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.8027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okano J, Gaslightwala I, Birnbaum MJ, Rustgi AK, Nakagawa H. Akt/Protein Kinase B isoforms are differentially regulated by epidermal growth factor stimulation in esophageal cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2000 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004112200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mayo LD, Donner DB. A phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway promotes translocation of Mdm2 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001 Sep 25;98(20):11598–603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181181198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou M, Gu L, Findley HW, Jiang R, Woods WG. PTEN reverses MDM2-mediated chemotherapy resistance by interacting with p53 in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Cancer Res. 2003 Oct 1;63(19):6357–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dumont P, Gasser B, Rouge C, Massard G, Wihlm JM. Bronchoalveolar carcinoma: histopathologic study of evolution in a series of 105 surgically treated patients. Chest. 1998 Feb;113(2):391–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin DM, Ma Y, Zheng S, Liu XY, Zou SM, Wei WQ. Prognostic value of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma component in lung adenocarcinoma. Histol Histopathol. 2006 Jun;21(6):627–32. doi: 10.14670/HH-21.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]