Summary

Recently, Paul Modrich’s group reported the discovery of an intrinsic endonuclease activity for human MutLα. This breakthrough provides a satisfactory answer to the longstanding puzzle of a missing nuclease activity in human mismatch repair and will undoubtedly lead to new investigations of DNA repair and replication. Here, the implications of this exciting new finding are discussed in the context of mismatch repair in E. coli and humans.

Correction of replication errors by mismatch repair (MMR) has long been recognized as critical for genomic stability. Inactivation of MMR in humans has been implicated in > 90% of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancers [1]. Like every DNA repair process, the success of MMR depends on two essential steps: lesion detection and removal. MMR is unique in two aspects. The targets of repair are normal rather than damaged nucleotides, and nucleotide removal has to be specific to the newly synthesized daughter strand and not the template. E. coli MMR is the best understood and has been fully reconstituted in vitro using a dozen or so purified proteins [2,3]. Recognition of a normal nucleotide that fails to make a Watson-Crick base pair in a DNA duplex is accomplished by the MutS protein. The strand specificity of MMR in E. coli is conferred by a sequence and methylation specific endonuclease MutH, which makes an incision (nick) 5′ to a GATC sequence in the unmethylated daughter strand. The GATC sequence may be several hundred base pairs from the mismatch on either the 5′ or 3′ side (Fig. 1A). The direction of daughter strand removal is strongly biased towards the shorter track between the nick and mismatch in a circular genome. The degradation of hundreds to a thousand nucleotides is carried out by one of several exonucleases with 5′ → 3′ or 3′—gt; 5′ polarity in the presence of the UvrD helicase and the single strand binding protein SSB. An additional central player in MMR is MutL, a molecular matchmaker that mediates protein-protein interactions and coordinates mismatch recognition with strand incision and degradation (Fig. 1A).

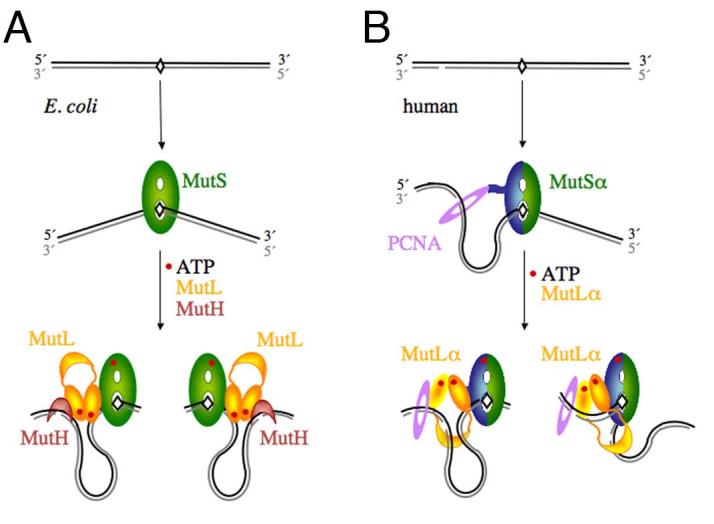

Figure 1.

Diagrams of the initial incision step of MMR in E.coli and humans. A. In E. coli, MutS recognizes a mismatch, binds it and bends the DNA by 60° towards the major groove. The newly synthesized and unmethylated daughter strand is shown in grey. In the presence of ATP, MutL is recruited to the MutS-mismatch complex, and together they activate MutH to nick the daughter strand on either the 5′ or 3′ side of the mismatch. Since the DNA binding activity of MutL is not necessary for this step and slightly inhibits MutH activation [34], we propose that the DNA in between the mismatch and incision site is looped out. B. In humans, MutSα is made of MSH2 (green) and MSH6 (blue) and interacts with PCNA (purple). The daughter strand is marked by a pre-existing strand break. A break 3′ to the mismatch is shown here as an example. MutSα may have a strand preference when loaded by PCNA. The ensuing MutSα-MutLα-mismatch complex could also be biased due to the asymmetric (heterodimeic) nature. Incisions by the PMS2 subunit of MutLα on the 3′ side of the mismatch may be guided by PCNA and MutSα, and incisions on the 5′ side may be limited by how far the C-terminal domain of MutLα (the endonuclease active site) can extend from the MutSα-MutLα complex located on the mismatch site.

The MMR pathway is conserved from E. coli to humans [3]. The essential proteins known to specialize in human MMR are so far limited to MutS and MutL homologs and a 5′ → 3′ exonuclease, ExoI. Eukaryotic MutS and MutL are heterodimers of homologous subunits as opposed to homodimers in bacteria. Human MutSα consists of MSH2 and MSH6, and MutLα consists of MLH1 and PMS2. A strand-specific endonuclease that nicks the daughter strand, like MutH in E. coli, is missing in all eukaryotes and in many bacteria. It is thus suspected that the discontinuities in the daughter strands due to the 3′ end or Okazaki fragments may designate the newly synthesized strand for MMR in these organisms. The remaining longstanding question is which nuclease removes a mismatch when the discontinuity is 3′ to the mismatch (3′ strand break) as the uni-directional ExoI only removes a mismatch when the break is 5′ to it (5′ strand break). Recently Paul Modrich and his colleagues at Duke University discovered that human MutLα has an intrinsic endonuclease activity. This endonucleolytic activity is activated by MutSα bound to a mismatch and the sliding clamp PCNA loaded by RFC at a free 3′ end, and it cleaves the discontinuous strand on either side of the mismatched base [4]. In principle, the endonuclease activity of MutLα and the 5′ → 3′ exonuclease of ExoI together can remove a mismatch from a 5′ or 3′ strand break.

The discovery of a MutL endonculease activity is a triumph of dogged pursuit by a group of very talented biochemists. Initially Drs. Genschel and Modrich, using mammalian cell extracts, showed that ExoI and MutSα are essential for mismatch removal from a 5′ strand break, but MutLα is required in addition when the break is 3′ to the mismatch [5]. Later, in vitro reconstitution of human MMR with purified proteins revealed the additional requirements for the sliding clamp PCNA and its loader RFC for 3′ directed MMR [6]. This finding coincided with an earlier report that PCNA was required for MMR prior to replacement strand synthesis [7]. The possibility of a cryptic 3′ → 5′ hydrolytic activity in ExoI was raised [6], but no evidence was found. Finally, with purified MutSα, MutLα, RFC and PCNA, an endonuclease activity, which weakly but specifically incises the discontinuous strand in a mismatch-containing heteroduplex, was detected and located in MutLα [4]. The authors further showed that the endonucleolytic activity of MutLα requires Mn2+ and ATP.

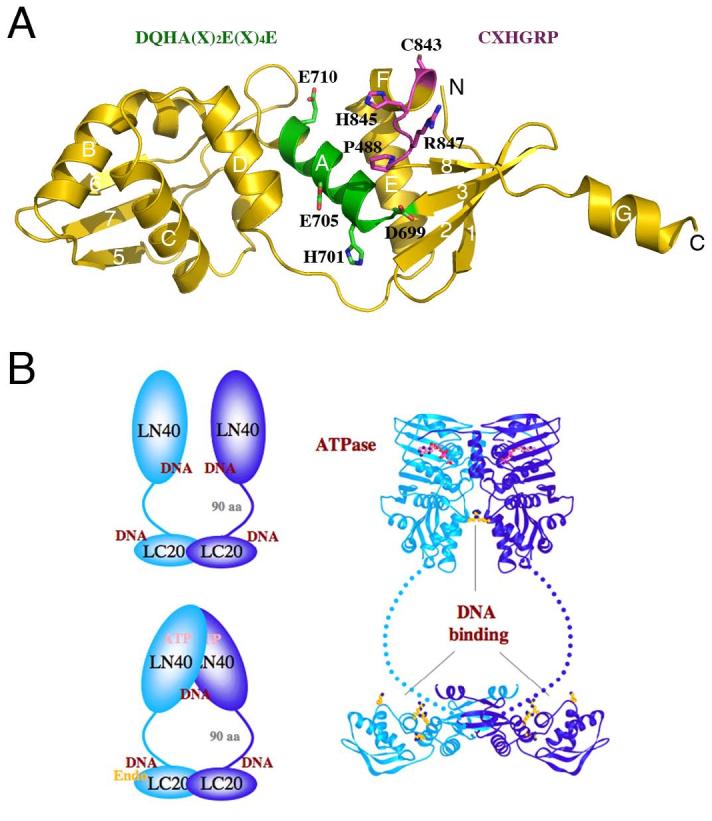

To ascertain that the low incision activity is intrinsic to MutLα and not due to a minor nuclease contamination, Kadyrov et al identified a divalent cation-binding site in the PMS2 subunit of MutLα by Fe2+-mediated hydroxyl radical “footprinting”. The binding site was mapped to the C-terminal region of PMS and included the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif. This motif is found in many eukaryotic and bacteria MutL proteins but not in MLH1 or E. coli MutL. Replacement of either the first Asp (D699 of hPMS2) or the middle Glu (E705 of hPMS2) with Ala eliminates the endonucleolytic activity of hMutLα [4]. This conserved motif is mapped onto an exposed surface of the C-terminal domain based on the crystal structure of the E. coli protein (Fig. 2A) since all MutL homologs are predicted to have a conserved tertiary fold [8,9]. Interestingly, the substitution within the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif of E. coli MutL includes two Arg residues, and these Arg sidechains were shown to be important for DNA binding (Fig. 2B) [8]. In the modeled PMS2 structure, the DQHA(X)2E(X)4E motif is juxtaposed to another sequence motif, CXHGRP, conserved among hPMS2-like MutL homologs (Fig. 2A) [8,9]. Although the overall structure and arrangement of the conserved residues in hPMSs do not immediately resemble any known nucleases, conserved Cys, His, Asp and Glu residues in this region can readily form a metal ion-binding site.

Figure 2.

Structural model of MutLα. A. A model of the C-terminal domain of PMS2 based on the E. coli MutL structure [8] (PDB accession: 1X9Z). The DQHA(X)2E(X)4E and CXHGRP motifs are highlighted in the ribbon diagram and written out above the diagram in the same color. B. The overall structure of an MutL dimer. The C-terminal domains of MutL form a stable dimer in E. coli and humans. The N-terminal ATPase domains associate in the presence of ATP and dissociate in its absence. The linker between the two domains contains ∼100-300 residues and adopts a rather extended conformation in E. coli MutL. Both the N- and C-terminal domains of E. coli and yeast MutL have been shown to interact with DNA. The DNA-binding region in the C-terminal domain of E. coli MutL coincides with the divalent cation-binding site in PMS2. Since MLH1 has no metal ion-binding site, MutLα is predicted to contain a single endonuclease active site. Homodimeric bacterial MutL proteins may have two endonuclease active sites per molecule, but the endonuclease activity may be asymmetric upon association with MutS and a mismatch site.

The relatively low and latent endonuclease activity of MutLα may explain why it eluded detection for a very long time. Conserved acidic residues in the rather diverse C-terminal domain of MutL homologs in eukaryotic and bacterial organisms that lack MutH homologs were noticeable. It even caught our imagination since conserved acidic residues are often a hallmark of the active site of phosphoryl transferases requiring divalent cations for catalysis. But a nuclease activity test of the purified C-terminal domains of human MutLα (a stable heterodimer of hMLH1 and hPMS2) was negative (Guarne & Yang, unpublished results). Using a reconstituted human MMR system with highly purified protein components, Guo-min Li’s group showed that MutLα negatively regulates the ExoI activity but has no nucleolytic activity itself and there is no 3′-directed MMR [10]. The difference between the two in vitro reconstituted systems, one with active and the other inactive MutLα endonuclease, is likely to be in the clamp loader RFC, the p38 subunit in particular [4].

MutL and its homologs are like a jack of all trades in MMR. When first identified, it was thought to have no enzymatic activity [11]. In 1994, the human MutL homolog MLH1 and PMS2 were implicated in the susceptibility to hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer [12,13]. In 1998, its ATPase activity was identified and shown to modulate the conformation and DNA binding properties of MutL (Fig. 2B) [14,15]. Now with the proper cofactors, MutLα is found to be an endonuclease! The new breakthrough provides a satisfactory solution to a longstanding puzzle and raises the following questions for future investigations of MMR. Firstly, is the MutLα endonuclease activity regulated to avoid unwanted DNA degradation? If so, how is it regulated? Secondly, the sites nicked by MutLα upon mismatch-dependent activation must be daughter-strand specific and localized around the mismatch site. What is the mechanism for such specificity?

The low intrinsic endonuclease activity of MutLα stimulated by MMR cofactors (MutSα, PCNA, RFC, ATP and divalent cations) resembles the characteristics of MutH in E. coli MMR. The latent MutH endonuclease is activated by MutS and MutL associated with a mismatch, but it can also be activated by MutL alone in the presence of ATP and Mg2+ [15-17]. To avoid non-mismatch-dependent activation, the MutH endonuclease activity needs to be negatively regulated. Both SeqA and the Dam methylase in E. coli bind and compete for hemimethylated GATC with much lower Kd’s (nM) than that of MutH (μM) [8,18-21]. They likely prevent MutH from accessing the newly synthesized daughter strand in the absence of a mismatch. Only in the presence of a mismatch, MutH is activated by MutS and MutL and gains access to its recognition site [21,22]. Activation of MutH is estimated to be moderate, ∼10 to 20 fold [3], but this may be sufficient to overcome the competition from SeqA and Dam methylase. Overexpression of Dam or SeqA by several fold leads to a mutator phenotype [23,24], which highlights the delicate balance between negative and positive regulation of the MutH endonuclease for genomic stability. Although the endonucleolytic activity of MutLα that relaxes supercoiled DNA requires Mn2+, which is virtually absent in vivo [4], MutLα does cleave DNA in the absence of a mismatch or MutSα if a strand break already exists and Mg2+, ATP, PCNA, RFC and RPA are present [4]. Since Mg2+, ATP, PCNA, RFC, RPA and strand breaks are abundant in S phase, one might speculate that there is at least one inhibitor in vivo to keep the MutLα endonuclease activity at bay before a mismatch is detected.

The second layer of regulation is the sites of cleavage by MutLα endonuclease during MMR, which are strongly biased towards the discontinuous strand and surrounding a mismatched base pair [4]. The preference for a discontinuous over continuous strand is unprecedented. In E. coli, after MutH makes a nick in the daughter strand, the UvrD helicase and an exonuclease follow the daughter strand from the nick towards the mismatch site in single nucleotide steps [3,8,25,26]. Kadyrov et al. showed that nicking by MutLα precedes daughter strand removal by ExoI [4]. It is perplexing how MutLα determines whether a DNA strand has a break tens or hundreds of base pairs away, particularly when a mismatch site bound by MutSα separates a preexisting break from the new cleavage site (Fig. 1B). Although bacterial homodimeric MutS cannot differentiate between template and daughter strands [3,27,28], yeast PCNA is loaded onto a template-daughter strand junction by RFC with a defined orientation [29], and Kolodner’s group showed that PCNA and the MSH6 subunit of MutSα form specific interactions prior to mismatch detection [30]. It is possible that MutSα may be oriented by PCNA and loaded onto DNA with strand bias (Fig. 1B).

The MutL ATPase activity is another feature to be considered for its significance in strand specificity. Kadyrov et al. showed that mutations that abolish MutLα ATP hydrolysis also prevent the 3′ break-directed incision [4]. The ATPase domain in the N-terminal region of MutL is highly conserved and resembles those of DNA gyrase and topoisomerase II [14,15]. Can MutLα sense DNA topology? Both the N- and C-terminal domains of E. coli MutL contribute to DNA binding, and the ATPase and DNA-binding activity are inter-dependent [8,14,15] (Fig. 2B). The residues involved in DNA binding are not conserved, but the DNA-binding property is conserved in yeast MutL homologs and is essential for MMR [31]. Whether and how DNA binding by MutLα influences the endonuclease activity is yet to be determined.

Besides nick-dependent strand specificity, MutLα is able to cleave DNA either 5′ or 3′ to a mismatched site. It appears to cleave roughly equidistant between the mismatch and a pre-existing strand break, which may span a few hundreds of base pairs. On the other side of the mismatch, it cleaves ∼ 100 base pairs from the mismatch. Kadyrov showed that the cleavage sites of MutLα endonuclease are much more dispersed in the reconstituted MMR system than in a system supplemented with nuclear extracts and proposed the existence of a regulator [4]. The regulatory factor missing in the reconstituted system may exert positive rather than negative effects. It may stabilize the MutSα-MutLα on a mismatch site and localize the incisions around the mismatch site. The extent of the cleavage range may also be a result of the flexible and extended nature of the MutLα molecule [8] and the influence of PCNA (Fig. 1B).

As we consider MMR in vivo and keep in mind that it occurs while DNA replication is ongoing, additional questions arise. While a mismatch, strand break, MutSα, PCNA and RFC are sufficient for MutLα endonuclease activation in vitro, many other PCNA-interacting proteins are prevalent during S phase. How does the interaction of MutLα mesh with a handful of different DNA polymerases, including those specialized in rescuing stalled replication forks, and many other DNA repair proteins? Does the presence of MutSα and MutLα on a mismatch prevent recruitment of DNA polymerase by RFC and PCNA? How does MMR compete with other DNA repair pathways? Kadyrov et al. suggest that it is the dual interaction of PCNA with both MutSα and MutLα [7,30,32,33] that may activate MMR. It will be of great interest to get to the bottom of the molecular interactions and their roles in genome stability.

Acknowledgement

We thank D. Leahy, P. Friedhoff and R. Craigie for reviewing the manuscript. This research was supported fully by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIDDK.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Peltomaki P. Lynch syndrome genes. Fam Cancer. 2005;4:227–232. doi: 10.1007/s10689-004-7993-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lahue RS, Au KG, Modrich P. DNA mismatch correction in a defined system. Science. 1989;245:160–164. doi: 10.1126/science.2665076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Iyer RR, Pluciennik A, Burdett V, L and P. Modrich DNA mismatch repair: functions and mechanisms. Chem Rev. 2006;106:302–323. doi: 10.1021/cr0404794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kadyrov FA, Dzantiev L, Constantin N, Modrich P. Endonucleolytic function of MutLalpha in human mismatch repair. Cell. 2006;126:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Genschel J, Bazemore LR, Modrich P. Human exonuclease I is required for 5′ and 3′ mismatch repair. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13302–13311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Dzantiev L, Constantin N, Genschel J, Iyer RR, Burgers PM, Modrich P. A defined human system that supports bidirectional mismatch-provoked excision. Mol Cell. 2004;15:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Umar A, Buermeyer AB, Simon JA, Thomas DC, Clark AB, Liskay RM, Kunkel TA. Requirement for PCNA in DNA mismatch repair at a step preceding DNA resynthesis. Cell. 1996;87:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Guarne A, Ramon-Maiques S, Wolff EM, Ghirlando R, Hu X, Miller JH, Yang W. Structure of the MutL C-terminal domain: a model of intact MutL and its roles in mismatch repair. Embo J. 2004;23:4134–4145. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kosinski J, Steindorf I, Bujnicki JM, Giron-Monzon L, Friedhoff P. Analysis of the quaternary structure of the MutL C-terminal domain. J Mol Biol. 2005;351:895–909. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhang Y, Yuan F, Presnell SR, Tian K, Gao Y, Tomkinson AE, Gu L, Li GM. Reconstitution of 5′-directed human mismatch repair in a purified system. Cell. 2005;122:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Grilley M, Welsh KM, Su SS, Modrich P. Isolation and characterization of the Escherichia coli mutL gene product. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:1000–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bronner CE, Baker SM, Morrison PT, Warren G, Smith LG, Lescoe MK, Kane M, Earabino C, Lipford J, Lindblom A, et al. Mutation in the DNA mismatch repair gene homologue hMLH1 is associated with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. Nature. 1994;368:258–261. doi: 10.1038/368258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nicolaides NC, Papadopoulos N, Liu B, Wei YF, Carter KC, Ruben SM, Rosen CA, Haseltine WA, Fleischmann RD, Fraser CM, et al. Mutations of two PMS homologues in hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. Nature. 1994;371:75–80. doi: 10.1038/371075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ban C, Junop M, Yang W. Transformation of MutL by ATP binding and hydrolysis: a switch in DNA mismatch repair. Cell. 1999;97:85–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80717-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ban C, Yang W. Crystal structure and ATPase activity of MutL: implications for DNA repair and mutagenesis. Cell. 1998;95:541–552. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81621-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ahrends R, Kosinski J, Kirsch D, Manelyte L, Giron-Monzon L, Hummerich L, Schulz O, Spengler B, Friedhoff P. Identifying an interaction site between MutH and the C-terminal domain of MutL by crosslinking, affinity purification, chemical coding and mass spectrometry. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:3169–3180. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Giron-Monzon L, Manelyte L, Ahrends R, Kirsch D, Spengler B, Friedhoff P. Mapping protein-protein interactions between MutL and MutH by cross-linking. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49338–49345. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409307200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Herman GE, Modrich P. Escherichia coli dam methylase. Physical and catalytic properties of the homogeneous enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:2605–2612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Slater S, Wold S, Lu M, Boye E, Skarstad K, Kleckner N. E. coli SeqA protein binds oriC in two different methyl-modulated reactions appropriate to its roles in DNA replication initiation and origin sequestration. Cell. 1995;82:927–936. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Guarne A, Zhao Q, Ghirlando R, Yang W. Insights into negative modulation of E. coli replication initiation from the structure of SeqA-hemimethylated DNA complex. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:839–843. doi: 10.1038/nsb857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lee JY, Chang J, Joseph N, Ghirlando R, Rao DN, Yang W. MutH complexed with hemi- and unmethylated DNAs: coupling base recognition and DNA cleavage. Mol Cell. 2005;20:155–166. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Schofield MJ, Nayak S, Scott TH, Du C, Hsieh P. Interaction of Escherichia coli MutS and MutL at a DNA mismatch. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:28291–28299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103148200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Herman GE, Modrich P. Escherichia coli K-12 clones that overproduce dam methylase are hypermutable. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:644–646. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.1.644-646.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yang H, Wolff E, Kim M, Diep A, Miller JH. Identification of mutator genes and mutational pathways in Escherichia coli using a multicopy cloning approach. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:283–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Dao V, Modrich P. Mismatch-, MutS-, MutL-, and helicase II-dependent unwinding from the single-strand break of an incised heteroduplex. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9202–9207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.9202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Yamaguchi M, Dao V, Modrich P. MutS and MutL activate DNA helicase II in a mismatch-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9197–9201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.9197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Obmolova G, Ban C, Hsieh P, Yang W. Crystal structures of mismatch repair protein MutS and its complex with a substrate DNA. Nature. 2000;407:703–710. doi: 10.1038/35037509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lamers MH, Perrakis A, Enzlin JH, Winterwerp HH, de Wind N, Sixma TK. The crystal structure of DNA mismatch repair protein MutS binding to a G x T mismatch. Nature. 2000;407:711–717. doi: 10.1038/35037523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bowman GD, Goedken ER, Kazmirski SL, O’Donnell M, Kuriyan J. DNA polymerase clamp loaders and DNA recognition. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:863–867. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lau PJ, Kolodner RD. Transfer of the MSH2.MSH6 complex from proliferating cell nuclear antigen to mispaired bases in DNA. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14–17. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200627200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hall MC, Shcherbakova PV, Fortune JM, Borchers CH, Dial JM, Tomer KB, Kunkel TA. DNA binding by yeast Mlh1 and Pms1: implications for DNA mismatch repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2025–2034. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gu L, Hong Y, McCulloch S, Watanabe H, Li GM. ATP-dependent interaction of human mismatch repair proteins and dual role of PCNA in mismatch repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1173–1178. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.5.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kleczkowska HE, Marra G, Lettieri T, Jiricny J. hMSH3 and hMSH6 interact with PCNA and colocalize with it to replication foci. Genes Dev. 2001;15:724–736. doi: 10.1101/gad.191201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Junop MS, Yang W, Funchain P, Clendenin W, Miller JH. In vitro and in vivo studies of MutS, MutL and MutH mutants: correlation of mismatch repair and DNA recombination. DNA Repair (Amst) 2003;2:387–405. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]