Abstract

Background

RNA interference coupled with videorecording of C. elegans embryos is a powerful method for identifying genes involved in cell division processes. Here we present a functional analysis of the gene B0511.9, previously identified as a candidate cell polarity gene in an RNAi videorecording screen of chromosome I embryonic lethal genes.

Results

Whereas weak RNAi inhibition of B0511.9 causes embryonic cell polarity defects, strong inhibition causes embryos to arrest in metaphase of meiosis I. The range of defects induced by RNAi of B0511.9 is strikingly similar to those displayed by mutants of anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) components. Although similarity searches did not reveal any obvious homologue of B0511.9 in the non-redundant protein database, we found that the N-terminus shares a conserved sequence pattern with the N-terminus of the small budding yeast APC/C subunit Cdc26 and its orthologues from a variety of other organisms. Furthermore, we show that B0511.9 robustly complements the temperature-sensitive growth defect of a yeast cdc26Δ mutant.

Conclusion

These data demonstrate that B0511.9 encodes the C. elegans APC/C subunit CDC-26.

Background

A major goal in biology is to understand the function of each gene. For many organisms, complete genome sequences are now available. Combined with knockdown techniques such as RNAi or morpholino oligos, genes can be quickly assayed for in vivo function [1,2]. In C. elegans, genome-wide knockdown of gene activity through RNAi has provided important phenotypic information for thousands of genes [3-8]. Although a useful starting point, much of the phenotypic information lacks detail; for example, many genes are only annotated as essential for viability.

Several studies have carried out additional analyses to identify more precise gene functions. In particular, RNAi videorecording screens have uncovered very detailed defects allowing genes to be grouped into more specific phenotypic classes [4,7-9]. However, within each class there still exist groups of genes with different functions. Analysing the phenotypes of individual genes in more depth is important for assigning genes to specific functions. Through an interest in embryonic polarity, we investigated the function of B0511.9, previously identified as having embryonic polarity defects in a large-scale RNAi videorecording screen [9]. Through phenotypic analyses, we show that B0511.9 shares functions with components of the cell cycle regulator, the anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C).

The APC/C is a complex of 12 subunits in animal cells (13 in yeast) that regulates destruction of key cell cycle regulators at the appropriate times by targeting them for degradation by the 26 S proteasome through its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity (reviewed in [10-12]). In C. elegans, nine of the 12 APC/C subunits have been identified based on sequence analysis [13-17]; Cdc26, Apc7, and Apc13 were not identified. For seven subunits, loss of function using mutants or RNAi causes an arrest at metaphase of meiosis I; for two (apc-5 and apc-10), weak embryonic lethality was seen along with germline maintenance problems consistent with mitotic defects (reviewed in [18]).

Results and Discussion

B0511.9 is required for the metaphase to anaphase transition of meiosis I

In large scale RNAi videorecording screens, RNAi of B0511.9 was shown to cause different phenotypes: loss of asymmetry in the first cell division or one cell arrest due to failure to pass through meiosis [8,9]; To understand the role of B0511.9 in cell division, we examined the RNAi phenotype in detail.

We first carried out a time course of RNAi feeding of B0511.9 and examined embryos laid at different times after RNAi was initiated in the mother (Table 1). RNAi knockdown increases in strength during the time course. There was an increase in lethality from 17.9% at 24–32 hours post feeding to 100% at 56 hours post feeding or later. The terminal arrest phenotypes of the embryos changed over time. At 24–32 hours post feeding, most arrested embryos contained many cells whereas embryos laid 56 hours after initiation of RNAi feeding arrested as a single cell (Table 1). At intermediate time points, both types of terminal arrest embryos were seen (Table 1).

Table 1.

Time course of RNAi of B0511.9

| Time post RNAi | Dead embryos (n) | Hatched embryos (n) | Phenotype of dead embryos |

| 24–32 hours | 17.9% (93) | 82.1% (425) | Multicellular |

| 32–48 hours | 31.1% (324) | 68.9% (719) | One cell arrest or multicellular |

| 48–56 hours | 81.6% (288) | 18.4% (65) | Predominantly one cell arrest |

| > 56 hours | 100% (93) | 0% | One cell arrest |

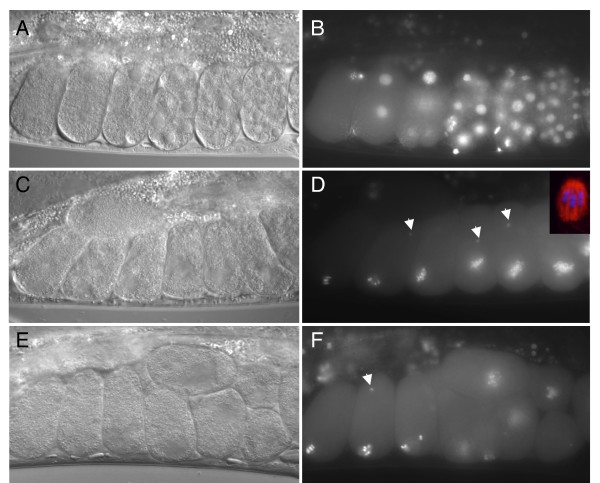

To investigate the arrest stage of the embryos after strong RNAi of B0511.9 we examined the pattern of DNA condensation of embryos inside the uterus using a GFP::histone reporter gene. Compared to the wild-type where progressively older embryos have progressively more cells (Figure 1A, B), embryos in the uteri of B0511.9(RNAi) mothers all showed the DNA condensation typical of metaphase of meiosis I (Figure 1C, D). Staining these arrested embryos for tubulin confirmed that embryos arrested with a meiosis I metaphase-like spindle (inset in Figure 1D). This phenotype is similar to that reported for mutants or strong RNAi of anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) subunits [13-15,17]. We confirmed that the phenotype of strong B0511.9(RNAi) embryos described above is identical to that seen after RNAi of APC/C component emb-27/Cdc16 (Figure 1E, F). These results indicate that like APC/C components, B0511.9 is required for progression from metaphase to anaphase of meiosis I.

Figure 1.

Meiotic metaphase arrest induced by strong RNAi of B0511.9. Pairs of pictures show DIC and fluorescence images of embryos in the uterus of a mother carrying a GFP::H2B transgene marking nuclei. (A, B) wild-type embryos show progressively more nuclei as divisions proceed. (C, D) B0511.9(RNAi) embryos are all arrested at the one cell stage; staining of such embryos for beta-tubulin (red) and DNA (blue) shows arrest stage is at meiotic metaphase I (inset). (E, F) emb-27/Cdc16(RNAi) embryos arrested in metaphase of meiosis I [15], a phenotype identical to that of B0511.9(RNAi) in (C, D). Arrows in (D) and (F) point to sperm chromatin, indicating that the embryos have been fertilized.

Weak depletion of B0511.9 causes embryonic polarity defects

We next examined the phenotype of embryos laid after shorter maternal RNAi of B0511.9, which should cause a weaker depletion. In wild-type embryos, the first cell division is asymmetric, occurring at 56% embryo length (range of 54–57%, n = 20). In contrast, we found that first division in B0511.9(RNAi) embryos is much more symmetric, occurring on average at 52% embryo length (range of 51–54%, n = 10). This suggests that B0511.9(RNAi) embryos have a defect in embryonic polarity.

In wild-type embryos, polarity is initiated during the first cell cycle, leading to the asymmetric localisation of PAR polarity proteins, with a complex of PAR-3/PAR-6/PKC-3 at the anterior cortex and PAR-1 and PAR-2 at the posterior cortex (reviewed in [19]). These proteins are required for the posterior displacement of the first mitotic spindle, which leads to an asymmetric cell division. In par mutant embryos, the first division is symmetric instead of asymmetric and the remaining PAR proteins are often mislocalized [19-26].

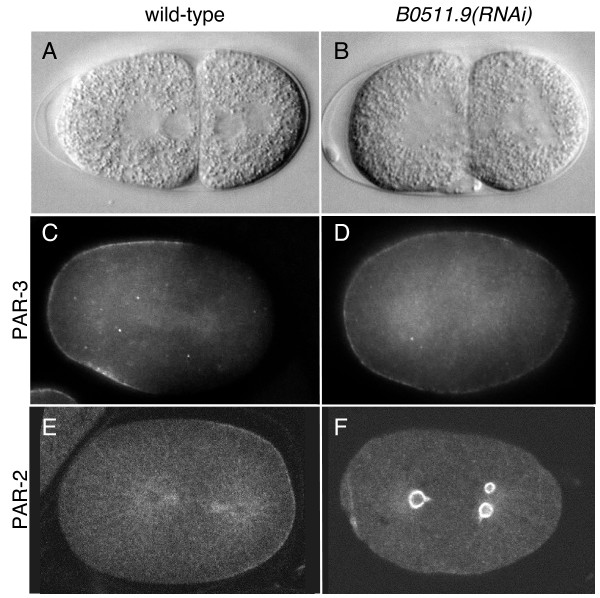

To determine whether RNAi of B0511.9 affected PAR polarity, we examined the localization of PAR-2 and PAR-3 in weakly affected B0511.9(RNAi) embryos. We found that these PAR proteins were abnormally distributed in 82% (n = 67) of such embryos, compared to 0% abnormal distribution in wild-type embryos (n = 30), indicating a defect in embryonic polarity. In most of B0511.9(RNAi) embryos, PAR-3 was expanded to encompass the entire cortex whereas PAR-2 was found in cytoplasmic puncta (Figure 2C–F and legend). This pattern is strikingly similar to that seen in partial loss of function mutants or weak RNAi of APC/C subunits emb-27/Cdc16, mat-1/Cdc27, mat-2/Apc1, mat-3/Cdc23, and emb-30/Apc4 [16]. The similarity in the range of phenotypes induced by RNAi of B0511.9 and APC/C components argues that B0511.9 functions with the APC/C.

Figure 2.

Embryonic polarity defects after weak RNAi of B0511.9. (A) wild-type 2 cell embryo after asymmetric first division; anterior AB cell is larger than the posterior P1 cell. (B) B0511.9(RNAi) embryo showing a symmetric first division. (C) PAR-3 at the anterior cortex of a wild-type one-celled embryo at anaphase. (D) PAR-3 on the entire cortex of a B0511.9(RNAi) embryo at anaphase. (E) PAR-2 at the posterior cortex of the wild-type one-celled embryo in (C). (F) PAR-2 in cytoplasmic structures in the B0511.9(RNAi) embryo shown in (D). The PAR-2 antibody shows weak cross-reaction with microtubules. PAR-2 and PAR-3 distributions were scored in wild-type and B0511.9(RNAi) embryos from prophase to the two cell stage. We distinguished weak versus strong classes of PAR staining defects in B0511.9(RNAi) embryos: (1) weak: an enlarged domain of cortical PAR-3 with a reduced domain of cortical PAR-2. (2) strong: complete cortical PAR-3 with PAR-2 in cytoplasmic puncta. In embryos where both meiotic divisions occurred, scored by the presence of two polar bodies, 50% were in the weak class and 17% in the strong class (n = 18). In embryos with a meiotic division defect, scored by the presence of only one polar body, 23% were in the weak class and 63% were in the strong class (n = 49). The PAR distribution defects in B0511.9(RNAi) embryos having two polar bodies suggests that its polarity function is separable from its meiotic function.

B0511.9 shows homology to the APC/C subunit Cdc26

There are two alternatively spliced isoforms of B0511.9 inferred from the sequence of ESTs, called B0511.9a and B0511.9b, which are predicted to encode proteins of 175aa and 187aa, respectively [27]. The final intron predicted in Wormbase [27] is not removed in the ESTs, making the proteins shorter than originally proposed due to an earlier stop codon. Homology searches using Blastp [28] with standard settings against the non-redundant protein database (NCBI) did not uncover any similarity of B0511.9 to any known protein. However, Blastp searches against the S. cerevisiae protein database revealed homology of the N-terminus of B0511.9 to the N-terminus of Cdc26.

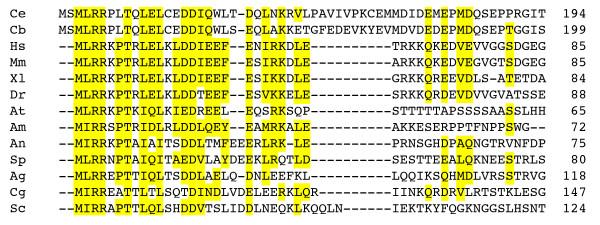

Budding yeast CDC26 encodes a small protein of 124 aa that is dispensable for proliferation at 25°C but essential for progression through mitosis at 37°C [29]. The protein resides within the APC/C where it stabilizes the association of the TPR repeat proteins Cdc16 and Cdc27 with other subunits of the complex [30,31]. Proteins related to Cdc26 have been found in the APC/C isolated from fission yeast and human cells [32,33]. Although the B0511.9 sequence is longer than those of other Cdc26 orthologues, it shares with all these proteins a conserved pattern of charged and large, hydrophobic residues at the very N-terminus (Figure 3). In contrast, the C-terminal regions of Cdc26 orthologues lack detectable sequence conservation. Indeed, the first 71 amino acids of S. cerevisiae Cdc26 are sufficient for proliferation albeit at a reduced rate [29].

Figure 3.

Multiple sequence alignment of N-terminal sequences from Cdc26 orthologues. All sequences start at the initiator methionine, and numbers give the total length of the protein. Conserved residues are highlighted in yellow. Ce, Caenorhabditis elegans (NP_740913, B0511.9); Cb, Caenorhabditis briggsae (CAE67051); Hs, Homo sapiens (NP_644815); Mm, Mus musculus (NP_647452); Xl, Xenopus laevis (BP677104); Dr, Danio rerio (NP_001004005); At, Arabidopsis thaliana (AAN10198); Am, Apis mellifera (XP_001122028); An, Aspergillus nidulans (AI210365); Sp, Schizosaccharomyces pombe (O13916, Hcn1); Ag, Ashbya gossypii (NP_984005); Cg, Candida glabrata (CAG60767); Sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae (NP_116694).

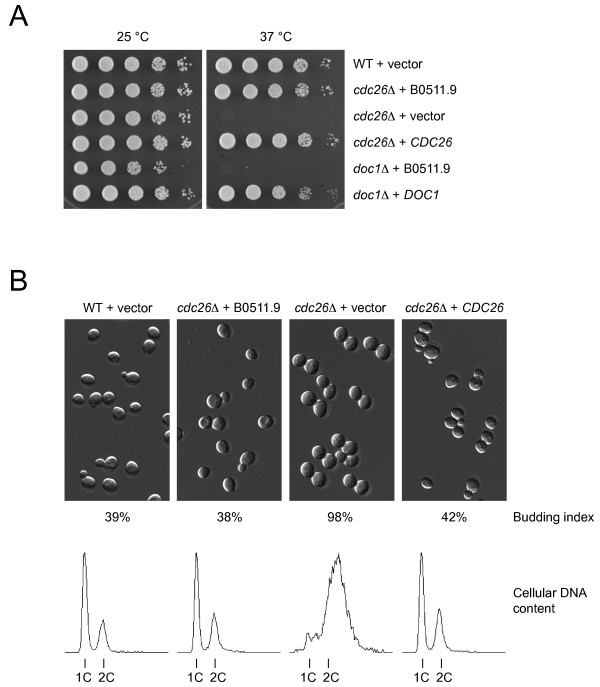

B0511.9 complements a budding yeast cdc26 mutant

To test whether B0511.9 could functionally replace Cdc26, we expressed it in S. cerevisiae cells lacking the endogenous CDC26 gene. As shown in Figure 4A, the B0511.9 plasmid but not the empty vector restored proliferation of cdc26Δ mutant cells at 37°C. Complementation was remarkably robust: cdc26Δ cells expressing B0511.9 grew with wild-type kinetics and were normal with respect to cell size, budding index, and cellular DNA content (Figure 4B). Expression of B0511.9 failed to rescue the temperature-sensitive growth defect of cells lacking another APC/C subunit, Doc1/Apc10. This result demonstrates that B0511.9 provides Cdc26 function to the yeast cells but does not rescue a general defect in APC/C activity.

Figure 4.

The C. elegans B0511.9 gene complements the proliferation defect of yeast cells lacking the CDC26 gene. (A) S. cerevisiae cells containing a deletion of CDC26 were transformed with a plasmid expressing the C. elegans B0511.9 gene from the yeast PGK promoter, or with the empty vector, or with a plasmid containing the yeast CDC26 gene. Wild type cells (WT) transformed with vector and cells lacking the DOC1/APC10 gene transformed with plasmids containing B0511.9 or the yeast DOC1 gene served as controls. Transformants were grown at 25°C in selective medium, normalized for cell density, and tenfold serial dilutions were spotted onto plates with rich medium. Shown are plates incubated at 25°C for 36 hours and at 37°C for 24 hours. (B) Strains from (A) were grown at 25°C and then shifted to 37°C for 5 hours. Shown are differential interference contrast pictures of the cells. Numbers indicate the percentage of budded cells in the indicated cultures. Graphs show cellular DNA content measured with a flow cytometer.

Conclusion

Our functional and phenotypic assays indicate that B0511.9 encodes the C. elegans APC/C subunit Cdc26 and accordingly we have named it cdc-26. Inhibition of cdc-26 activity leads to the same range of defects as seen after inhibition of other APC/C subunits, namely embryonic polarity defects after weak knockdown, and meiotic metaphase I arrest following strong knockdown. Consistent with the role of yeast Cdc26 in stabilizing the association of Cdc16 with other subunits, a large-scale two-hybrid study in C. elegans showed that CDC-26 binds to APC/C component EMB-27/Cdc16 [34].

Previous studies had identified C. elegans homologs of 9 of the 12 known human APC/C subunits (reviewed in [18]). No sequences with significant matches to Cdc26, Apc7, or Apc13 had been found. This study illustrates the power of RNA interference screens coupled with detailed phenotypic analyses in assigning gene function. RNAi embryo videorecording data for hundreds of genes are available [4,7-9]. In many cases, the defects observed in these movies give insight into the biological process affected. Further study of genes in different phenotypic classes will provide a deeper understanding into the mechanisms of shared cell division processes. For example, careful analyses of these data may lead to the identification of C. elegans Apc7 and Apc13.

Methods

Strains

The following strains were used and cultured by standard methods [35]: wild-type Bristol N2, AZ212: unc-119(ed3) ruIs32 [unc-119(+) pie-1::gfp::H2B] [36].

RNA interference

RNAi was carried out by feeding [37] as in [38] using RNAi feeding clones from [3,5]. Sequences of the clones are available in Wormbase [27] as sjj_B0511.9 for B0511.9 and as sjj_F10B5.6 for emb-27. For the time course in Table 1, wild-type N2 L4 hermaphrodites were placed on RNAi feeding plates containing the same bacterial strain at 20°C for 24 hours, then moved to new RNAi feeding plates for the indicated collection times. Embryos laid on each plate were scored the next day for embryo hatching and terminal phenotype. Fertilized embryos were easily distinguished from unfertilized oocytes by their oblong rather than rounded shape and presence of an eggshell, visible in the dissecting microscope. For strong RNAi of B0511.9 in Figure 1, GFP::H2B L4 hermaphrodites were placed on feeding plates for 30 hours at 25°C and then scored by DIC and GFP microscopy; for RNAi of emb-27/Cdc16, RNAi feeding was for 20 hours. For weak RNAi of B0511.9 in Figure 2 and for videorecording analyses, wild-type N2 L4s were placed on feeding plates for 40 hours at 20°C, then embryos dissected and processed for antibody staining or videorecording.

Embryo analyses

Videorecordings were done as in [9]. Antibody staining was done as in [22]. The PAR-3 antibody was raised in rat using GST-PAR-3 described in [21] and then affinity purified against the same protein after preclearing the serum of anti-GST antibodies. The PAR-2 antibody was raised in rabbit against N-terminally His-tagged full length PAR-2 and then affinity purified against the His-tagged N-terminus of PAR-2 (amino acids 1–100). Secondary antibodies were from Jackson Immunoresearch.

Yeast experiments

The cdc26Δ::KanMX4 strain and the corresponding wild-type are in the BY4741 genetic background (MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0) and were obtained from the European Saccharomyces cerevisiae Archive for Functional Analysis (EUROSCARF). The doc1Δ::KanMX4 deletion allele was introduced into the W303 background (MATa ade2-1 trp1-1 can1-100 leu2-3,112 his3-11,15 ura3-1).

To express C. elegans B0511.9a in yeast, a cDNA in the donor vector pDONR201 was obtained from [39] and then transferred to the expression destination vector pVV214 using GATEWAY recombinational cloning [40]. The resulting plasmid pJA189 contains an URA3 marker, the yeast 2-micron origin, and expresses B0511.9a from the PGK promoter. Translation starts at the second methionine of the original B0511.9a sequence where the homology with other Cdc26 orthologues begins (see Figure 3). To construct positive controls for the complementation of yeast mutants, yeast CDC26 and DOC1 were cloned into the vectors YCplac33 [41] and pRS426 [42], respectively. Standard protocols were used to transform yeast and to prepare growth media [43]. To determine the budding index > 200 cells were counted after brief sonication. To measure cellular DNA content cells were stained with propidium iodide and analyzed on a Becton Dickinson FACScan flow cytometer.

Bioinformatics

Database searches were performed at the National Center for Biotechnology Information with Tblastn and Blastp [28]. Multiple sequence alignments were generated with ClustalX [44] and edited manually.

Authors' contributions

YD participated in the design of the study, performed the experiments described in Figures 1 and 2 and Table 1, and helped to draft the paper; BH did the alignment in Figure 3; AB and WZ did the experiment described in Figure 4; JA conceived the study and participated in its design; JA and WZ wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Richard Durbin, Bruno Fievet, Gino Poulin, and Josana Rodriguez and anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript and Ken Kemphues for reagents. Some strains used in this work were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the NIH National Center for Research Resources (NCRR). YD and JA are supported by the Wellcome Trust (054523). Work in the WZ lab is supported by the Max Planck Society.

Contributor Information

Yan Dong, Email: yd208@mole.bio.cam.ac.uk.

Aliona Bogdanova, Email: bogdanova@mpi-cbg.de.

Bianca Habermann, Email: habermann@mpi-cbg.de.

Wolfgang Zachariae, Email: zachariae@mpi-cbg.de.

Julie Ahringer, Email: jaa@mole.bio.cam.ac.uk.

References

- Ekker SC. Morphants: a new systematic vertebrate functional genomics approach. Yeast. 2000;17:302–306. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(200012)17:4<302::AID-YEA53>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser AG, Kamath RS, Zipperlen P, Martinez-Campos M, Sohrmann M, Ahringer J. Functional genomic analysis of C. elegans chromosome I by systematic RNA interference. Nature. 2000;408:325–330. doi: 10.1038/35042517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonczy P, Echeverri C, Oegema K, Coulson A, Jones SJ, Copley RR, Duperon J, Oegema J, Brehm M, Cassin E, Hannak E, Kirkham M, Pichler S, Flohrs K, Goessen A, Leidel S, Alleaume AM, Martin C, Ozlu N, Bork P, Hyman AA. Functional genomic analysis of cell division in C. elegans using RNAi of genes on chromosome III. Nature. 2000;408:331–336. doi: 10.1038/35042526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath RS, Fraser AG, Dong Y, Poulin G, Durbin R, Gotta M, Kanapin A, Le Bot N, Moreno S, Sohrmann M, Welchman DP, Zipperlen P, Ahringer J. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature. 2003;421:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nature01278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda I, Kohara Y, Yamamoto M, Sugimoto A. Large-scale analysis of gene function in Caenorhabditis elegans by high-throughput RNAi. Curr Biol. 2001;11:171–176. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piano F, Schetter AJ, Mangone M, Stein L, Kemphues KJ. RNAi analysis of genes expressed in the ovary of Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1619–1622. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00869-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnichsen B, Koski LB, Walsh A, Marschall P, Neumann B, Brehm M, Alleaume AM, Artelt J, Bettencourt P, Cassin E, Hewitson M, Holz C, Khan M, Lazik S, Martin C, Nitzsche B, Ruer M, Stamford J, Winzi M, Heinkel R, Roder M, Finell J, Hantsch H, Jones SJ, Jones M, Piano F, Gunsalus KC, Oegema K, Gonczy P, Coulson A, Hyman AA, Echeverri CJ. Full-genome RNAi profiling of early embryogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2005;434:462–469. doi: 10.1038/nature03353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipperlen P, Fraser AG, Kamath RS, Martinez-Campos M, Ahringer J. Roles for 147 embryonic lethal genes on C.elegans chromosome I identified by RNA interference and video microscopy. Embo J. 2001;20:3984–3992. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.3984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passmore LA. The anaphase-promoting complex (APC): the sum of its parts? Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:724–727. doi: 10.1042/BST0320724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JM. The anaphase-promoting complex: proteolysis in mitosis and beyond. Mol Cell. 2002;9:931–943. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00540-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pines J. Mitosis: a matter of getting rid of the right protein at the right time. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis ES, Wille L, Chestnut BA, Sadler PL, Shakes DC, Golden A. Multiple subunits of the Caenorhabditis elegans anaphase-promoting complex are required for chromosome segregation during meiosis I. Genetics. 2002;160:805–813. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.2.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuta T, Tuck S, Kirchner J, Koch B, Auty R, Kitagawa R, Rose AM, Greenstein D. EMB-30: an APC4 homologue required for metaphase-to-anaphase transitions during meiosis and mitosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:1401–1419. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.4.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden A, Sadler PL, Wallenfang MR, Schumacher JM, Hamill DR, Bates G, Bowerman B, Seydoux G, Shakes DC. Metaphase to anaphase (mat) transition-defective mutants in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1469–1482. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.7.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappleye CA, Tagawa A, Lyczak R, Bowerman B, Aroian RV. The anaphase-promoting complex and separin are required for embryonic anterior-posterior axis formation. Dev Cell. 2002;2:195–206. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakes DC, Sadler PL, Schumacher JM, Abdolrasulnia M, Golden A. Developmental defects observed in hypomorphic anaphase-promoting complex mutants are linked to cell cycle abnormalities. Development. 2003;130:1605–1620. doi: 10.1242/dev.00385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeong FM. Anaphase-promoting complex in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:2215–2225. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.6.2215-2225.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro EM. PAR proteins and the cytoskeleton: a marriage of equals. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemphues KJ, Priess JR, Morton DG, Cheng NS. Identification of genes required for cytoplasmic localization in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1988;52:311–320. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(88)80024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etemad-Moghadam B, Guo S, Kemphues KJ. Asymmetrically distributed PAR-3 protein contributes to cell polarity and spindle alignment in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1995;83:743–752. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Kemphues KJ. par-1, a gene required for establishing polarity in C. elegans embryos, encodes a putative Ser/Thr kinase that is asymmetrically distributed. Cell. 1995;81:611–620. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung TJ, Kemphues KJ. PAR-6 is a conserved PDZ domain-containing protein that colocalizes with PAR-3 in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Development. 1999;126:127–135. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuse Y, Izumi Y, Piano F, Kemphues KJ, Miwa J, Ohno S. Atypical protein kinase C cooperates with PAR-3 to establish embryonic polarity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1998;125:3607–3614. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.18.3607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts JL, Etemad-Moghadam B, Guo S, Boyd L, Draper BW, Mello CC, Priess JR, Kemphues KJ. par-6, a gene involved in the establishment of asymmetry in early C. elegans embryos, mediates the asymmetric localization of PAR-3. Development. 1996;122:3133–3140. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd L, Guo S, Levitan D, Stinchcomb DT, Kemphues KJ. PAR-2 is asymmetrically distributed and promotes association of P granules and PAR-1 with the cortex in C. elegans embryos. Development. 1996;122:3075–3084. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wormbase http://www.wormbase.org

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki H, Awane K, Ogawa N, Oshima Y. The CDC26 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is required for cell growth only at high temperature. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;231:329–331. doi: 10.1007/BF00279807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwickart M, Havlis J, Habermann B, Bogdanova A, Camasses A, Oelschlaegel T, Shevchenko A, Zachariae W. Swm1/Apc13 is an evolutionarily conserved subunit of the anaphase-promoting complex stabilizing the association of Cdc16 and Cdc27. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3562–3576. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.8.3562-3576.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariae W, Shin TH, Galova M, Obermaier B, Nasmyth K. Identification of subunits of the anaphase-promoting complex of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 1996;274:1201–1204. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gmachl M, Gieffers C, Podtelejnikov AV, Mann M, Peters JM. The RING-H2 finger protein APC11 and the E2 enzyme UBC4 are sufficient to ubiquitinate substrates of the anaphase-promoting complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8973–8978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H, Kumada K, Yanagida M. Distinct subunit functions and cell cycle regulated phosphorylation of 20S APC/cyclosome required for anaphase in fission yeast. J Cell Sci. 1997;110 ( Pt 15):1793–1804. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.15.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Armstrong CM, Bertin N, Ge H, Milstein S, Boxem M, Vidalain PO, Han JD, Chesneau A, Hao T, Goldberg DS, Li N, Martinez M, Rual JF, Lamesch P, Xu L, Tewari M, Wong SL, Zhang LV, Berriz GF, Jacotot L, Vaglio P, Reboul J, Hirozane-Kishikawa T, Li Q, Gabel HW, Elewa A, Baumgartner B, Rose DJ, Yu H, Bosak S, Sequerra R, Fraser A, Mango SE, Saxton WM, Strome S, Van Den Heuvel S, Piano F, Vandenhaute J, Sardet C, Gerstein M, Doucette-Stamm L, Gunsalus KC, Harper JW, Cusick ME, Roth FP, Hill DE, Vidal M. A map of the interactome network of the metazoan C. elegans. Science. 2004;303:540–543. doi: 10.1126/science.1091403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praitis V, Casey E, Collar D, Austin J. Creation of low-copy integrated transgenic lines in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2001;157:1217–1226. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.3.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmons L, Fire A. Specific interference by ingested dsRNA. Nature. 1998;395:854. doi: 10.1038/27579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahringer (ed.) J. Reverse genetics. In: The C. elegans Research Community, editor. Wormbook. Wormbook; http://www.wormbook.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Reboul J, Vaglio P, Rual JF, Lamesch P, Martinez M, Armstrong CM, Li S, Jacotot L, Bertin N, Janky R, Moore T, Hudson JR, Jr., Hartley JL, Brasch MA, Vandenhaute J, Boulton S, Endress GA, Jenna S, Chevet E, Papasotiropoulos V, Tolias PP, Ptacek J, Snyder M, Huang R, Chance MR, Lee H, Doucette-Stamm L, Hill DE, Vidal M. C. elegans ORFeome version 1.1: experimental verification of the genome annotation and resource for proteome-scale protein expression. Nat Genet. 2003;34:35–41. doi: 10.1038/ng1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Mullem V, Wery M, De Bolle X, Vandenhaute J. Construction of a set of Saccharomyces cerevisiae vectors designed for recombinational cloning. Yeast. 2003;20:739–746. doi: 10.1002/yea.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz RD, Sugino A. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene. 1988;74:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson TW, Sikorski RS, Dante M, Shero JH, Hieter P. Multifunctional yeast high-copy-number shuttle vectors. Gene. 1992;110:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90454-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amberg DC, Burke DJ, Strathern JN. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY , Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]