Abstract

This paper describes the rationale for a randomized controlled trial, comparing cognitive behavior therapy in addition to treatment as usual with treatment as usual alone, for borderline personality disorder. Previous pioneering randomized controlled trials of psychotherapies have suffered from methodological weaknesses and have not always been reported clearly to allow adequate evaluation of either the individual study or comparisons across studies to be undertaken. We report on the recruitment and randomization, design, and conduct of an ongoing randomized controlled trial of one hundred and six patients with borderline personality disorder. Primary and secondary hypotheses and their planned analyses are stated. The baseline characteristics of 106 patients meeting diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder are described.

Those with borderline personality disorder (BPD) make great use of psychiatric services (Zanarini, Frankenburg, Hennen, & Silk, 2004), show a high prevalence of suicidal and self-injurious behavior (Mehlum, Friis, Vaglum, & Karterud, 1994) and demonstrate long-standing impairment in a wide variety of domains including difficulties in personal and social role functioning and impulse and affect regulation. There are indications that childhood adversity, genetic and neurobiological factors may play some role in the etiology of the disorder (Lieb, Zanarini, Schmahl, Linehan, & Bohus, 2004).

RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS FOR BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER

There are consistent indications from published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that psychotherapeutic approaches are beneficial in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: psychodynamic oriented therapy (Munroe-Blum & Marziali, 1995), psychodynamic informed partial hopitalization (Bateman & Fonagy, 1999, 2001), and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) (Linehan, Armstrong, Suarez, Allmon, & Heard, 1991; Linehan, Heard, & Armstrong, 1993; Linehan, Tuket, Heard, & Armstrong 1994; Verheul, van den Bosch, Koeter, de Ridder, Stijnen, & van den Brink, 2003; Koons et al., 2001; Turner, 2000). Table 1 describes the available randomized controlled trials. To avoid bias in reporting randomized controlled trials, the design, conduct, analysis and interpretation should be transparent (Moher, Schulz, Altman, & for the CONSORT Group, 2001). From the RCTs in Table 1, it would seem that all therapeutic approaches reduced self-harm when compared with a control treatment with the exception of DBT in one trial (Koons et al., 2001). Koons et al. (2001), unlike Linehan et al. (1991), found that DBT was superior to treatment as usual (TAU) on measures such as hopelessness and suicidal ideation. Koons et al. (2001) suggested that their sample may have been less behaviorally extreme than the participants in Linehan’s study (only 40% reported self harm at baseline) and may therefore have been more amenable to changes at an emotional and cognitive level.

TABLE 1.

Randomized Controlled Trials for Borderline Personality Disorder

| Psychodynamic Therapy | Dialectical Behavior Therapy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Munroe-Blum and Marziali (1995) | Bateman & Fonagy (1999; 2001) | Linehan et al. (1991)(1993) | Verheul et al. (2003) | Koons et al. (2001) | Turner (2000) |

| Sample | BPD men and women. Not required to have recent parasuicidal episode 1 center |

BPD men and women. Not required to have recent parasuicidal episode 1 center |

BPD women. Required recent parasuicidal episode. 1 center |

BPD women Not required to have recent parasuicidal episode 1 center |

BPD women veterans. Not required to have recent parasuicidal episode 1 center |

BPD men and women. Referred to community mental health outpatients treatment after suicide attempt. 1 center |

| Design | RCT | RCT | RCT | RCT | RCT | RCT |

| Treatment format | Interpersonal Group psychotherapy vs. Individual dynamic psychotherapy (one year) in 5 cohorts Follow-up 12 months | Psychoanalytically informed day hospital (PH) vs. TAU (18 months) Group + individual Follow-up 18 months | DBT vs. TAU (12 months) Group + individual Naturalistic follow-up 12 months | DBT (12 months) vs. TAU Group + individual No follow-up | DBT vs. TAU 6 months treatment Group + individual No follow-up | DBT oriented therapy vs. client centered treatment CCT. Both treatment 12 months. No follow-up. |

| Number randomized | n = 110 | n = 44 |

n = 63 (2 cohorts) |

n = 64 | n = 28 | n = 26 |

| Drop out from study | 31(28%) withdrew following randomization. Further 14 less than 3 sessions treatment (13%). n = 45 (41%) overall. |

16 out of 60 (27%) either refused randomization or would not comply with study requirements. 3 controls crossed over to PH. 3 in PH dropped out within 6 months. n = 6 (13.6%). No drop out from TAU. |

10 withdrew following randomization and further 7 dropped by investigators for refusing to comply with study conditions n = 17 (27%). 2 less than 4 sessions. n = 19 (30%): attrition from treatment DBT (16%), TAU (14%) |

2 refused treatment allocation and dropped from analysis, 4 DBT refused treatment n = 6 (10%). Of those entering treatment, attrition rate DBT N = 14 (37%); TAU, N = 26 (77%). | n = 3 dropped out at beginning of study. (11%) Drop out from treatment TAU, N = 2 (17%), DBT, n = 3 (23%) N = 8 (29%) overall. | 2 withdrew after randomization; 9 withdrew during treatment DBT(N = 3) & CCT(N = 6) (11/ 26:42% overall). N = 15 patients in treatment at 12 months |

| Analysis | No | No. N = 38. | No | Yes | No, completers only | Yes. N = 24 |

| Intention to treat? | n = 48 | Intention to treat analysis at follow-up | N = 44 | N = 47 | N = 20 | |

| Measures of deliberate self-harm | Objective Behaviors Index (included suicide attempts but not self-mutilation) | Suicide and Self-Harm Inventory: Suicide attempts episodes + self- mutilation | Parasuicide History Interview (PHI) Number of suicidal episodes or acts that require medical attention or treatment | Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index: suicidal behaviors. Lifetime Parasuicide Count: self- mutilating behaviors | Parasuicide History Interview (PHI) Number of suicidal episodes or acts that require medical attention or treatment | Target behavioral ratings 0-8 scale assessor rated |

| Blindness of assessors | Unclear | Unclear but measures self-report | Yes | Yes though doubts about maintenance of blindness | Yes | Yes |

| Results | IGP = individual psychotherapy at one year and at 12 month follow-up | PH > TAU at 18 months all measures PH > TAU 18 months follow-up (except trait anxiety) |

DBT > TAU (end treatment) for parasuicidal acts and inpatient days, anger, social adjustment etc (interview rated). DBT = TAU 12 month F-up | For Parasuicidal behavior DBT = TAU Self-mutilation DBT > TAU Impulsive behavior DBT > TAU |

Post treatment: DBT > TAU Hopelessness, depression anger suicidal ideation. DBT = TAU on suicidal attempts, HRSD depression & anxiety, dissociation, inpatient days. | Both treatments showed improvments. DBT > CCT at 6 & 12/12 for self-harm/suicide, anger, impulsiveness, global mental health, hospitalization. DBT = CCT anxiety |

| Comments | Large drop out rate. | Active elements of treatment unclear. Small sample size. Follow-up consisted of continuation of less intensive treatment for PH group | Women only. Small sample size. Large drop out rate for TAU. | Women only. Small sample size. Large drop out rate for TAU & DBT. No follow-up. | TAU more systematized leading to less drop out. Small sample size. No follow-up. | No follow-up. No control group used. Therapist helping alliance accounted for as much variance in patient’s improvement as the differences between treatment conditions. |

Lifetime Parasuicide Count: Comtois, K. A. & Linehan, M. M. (1999) Lifetime ‘Parasuicide Count (LPC). Seattle. University of Washington.

Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index: suicidal behaviours Arntz, A., Hoorn, M., yan den Cornelis, J., et al. (2003). Reliability and validity of the Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index. Journal of Personality Disorders, 17, 54-49.

Parasuicide History Interview. Linehan MM, Wagner AW, Cox G. (1989). Parasuicide History Interview: Comprehensive Assessment of Parasuicidal Behavior. Seattle: University of Washington.

Suicide and Self-Harm Inventory, available by request from Dr. A. Bateman.

Although the above findings may be cause for optimism, several methodological problems limit the findings and their generalizability. Taking the studies as a whole, in all but one study sample sizes are small (range 24 to 64) and there is a general absence of discussion of sample size considerations. Between 1% and 42% of patients referred to the studies withdrew because of difficulties accepting randomization, or were withdrawn by investigators because of likely non-compliance with study requirements. From the information available, once in treatment, attrition rates vary from 13.6% to 37% for the experimental treatment and between 0% and 77% for the control treatment. Attrition rates from either DBT or psychodynamically oriented treatment are more similar than attrition rates for treatment as usual suggesting greater variation in TAU between studies. Apart from Linehan et al. (1991, 1994), Turner (2000) and Verheul et al. (2003), the analysis of data at the end of treatment was for completers only and not by intention to treat. Additional methodological problems include patients breaking randomization allocation, crossing over to the experimental treatment in one study, and the data from those patients being included in the non-randomized group in the analysis (Bateman & Fonagy, 1999). In terms of follow-up, only one of the DBT trials has followed-up patients at the end of a finite amount of treatment to investigate the naturalistic outcome (Linehan et al., 1994). Bateman and Fonagy (2001) report on patients who continued to receive active treatment throughout the follow-up period, thereby blurring the definition of follow-up. The therapy patients received has not always been clearly specified and all randomized controlled trials focusing on borderline personality disorder have included a group therapy component in addition to other interventions, making it impossible to disentangle the effect of each separately. Only one study had a measure of therapist competence (Koons et al., 2001), a factor known to have an impact on treatment outcome in a post hoc analysis (Davidson, Scott, Schmidt, Tata, Thornton, & Tyrer, 2004). All studies have reported findings from single centers only and therefore the degree to which findings might be replicated in other sites is unknown. With the exception of one study comparing DBT with client-centered therapy (Turner, 2000), the effectiveness of DBT has only been assessed in women. The above studies have been pioneering, decreasing therapeutic nihilism for this group of patients but future studies should improve on their methodological limitations.

As yet, there are no published randomized controlled trials examining the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for borderline personality disorder. CBT is a structured, time limited, individual treatment that is problem focused and less intensive in therapist time than other forms of psychotherapy developed for borderline personality disorder. A previous study evaluated CBT in twelve borderline and antisocial personality disordered patients using single case methodology (Davidson & Tyrer, 1996) and demonstrated that CBT was clinically effective in reducing self-harm and reducing self destructive behaviors and, in an abbreviated form, shown to be favorable to patients who repeatedly self-harm, some of whom had personality disorder (Evans et al., 1999). In an open trial of cognitive therapy, patients with borderline personality disorder showed significant improvements after weekly sessions over one year that continued to be maintained at 18-months follow-up (Brown, Newman, Charlesworth, Crits-Christoph, & Beck, 2004).

We are currently evaluating the effectiveness of cognitive therapy in addition to treatment as usual in a randomized controlled trial of patients with borderline personality disorder. We anticipate that the addition of cognitive behavioral therapy to treatment as usual (CBT plus TAU) will decrease the number of participants with in-patient psychiatric hospitalizations or accident and emergency room contact or suicidal acts over twelve months treatment and twelve months follow-up, compared with treatment as usual (TAU). We also anticipate that CBT plus TAU will lead to superior improvement in quality of life, social, cognitive, and mental health functioning compared to TAU alone.

Having set out the rationale for a more methodologically rigorous trial in this area, we now describe the main hypothesis, the study design and statistical analysis plan, and give details of the CBT treatment arm, the baseline characteristics of participants.

METHOD

TRIAL DESIGN

The trial is being carried out in three centers in the United Kingdom: Glasgow, London, and Ayrshire (Ayrshire & Arran). The study sites were chosen because they are representative of both rural and urban centers and could generate sufficient referrals to the trial. All centers have existing community mental health teams and all have, to a greater or lesser extent, opportunity for patients to be referred to specialist services such as psychodynamic psychotherapy or clinical psychology. Treatment as usual (TAU) therefore reflected what is likely to be available in the United Kingdom, that is community based mental health services, in-patient psychiatric treatment and accident and emergency services in general hospital settings.

Patients were eligible if they satisfied the following criteria:

Aged between 18 and 65.

Met criteria for at least 5 items of the borderline personality disorder using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II; First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams, & Benjamin, 1997).

Had received either in-patient psychiatric services or an assessment at accident and emergency services or an episode of deliberate self-harm (either suicidal act or self-mutilation) in the previous 12 months.

Able to give informed consent.

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

Currently receiving in-patient treatment for a mental state disorder

Currently receiving a systematic psychological therapy or specialist service particularly psychodynamic psychotherapy

Insufficient knowledge of English to enable them to be assessed adequately and to understand the treatment approach

Temporarily resident in the area

The existence of an organic illness, mental impairment, alcohol or drug dependence, schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder, as assessed by SCID I,/P (W/Psychotic Screen), (version 2); (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996)

RECRUITMENT AND RANDOMIZATION

Recruitment took place over 8 months (February 1, 2002 to September 30, 2002). Participants were identified by clinicians from new and existing patients referred to community mental health teams, clinical psychology and liaison psychiatry services, providing that they were not receiving a specific psychological treatment for their personality disorder. After agreement to be contacted, a research assistant invited participants to take part in an interview to confirm the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder and inclusion criteria. Research assistants were trained in the SCID-II by a senior member of the team (P. Tyer), experienced in its use with personality disorders. Those participants who met the inclusion criteria and who agreed to give written informed consent to take part in the study then completed baseline assessments and were randomly allocated to either one of two active treatment groups namely, TAU, or CBT plus TAU.

Randomization was stratified by center, (Ayrshire, Glasgow, & London) and by high (presence of suicidal acts in past 12 months) or low (presence of self mutilation only in past 12 months) episodes of self-harm, using randomized permuted blocks of size 4. The randomization schedules were generated by the study data center at the Robertson Centre for Biostatistics, Glasgow University, and kept securely and confidentiality by the trial coordinator at the Study Coordinating Centre at the Dept. of Psychological Medicine. The researcher contacted the trial coordinator by telephone to initiate a randomization, with the researcher remaining blind to the allocation. The trial coordinator informed the referring agent of the result of randomization immediately and in writing, and then contacted the CBT therapist/s in each area with the patients details so that CBT therapy could be initiated.

EXPERIMENTAL INTERVENTION

Cognitive Behavior Therapy plus Treatment as Usual (CBT plus TAU) for Borderline Personality Disorder

CBT is a structured, time limited, psychosocial intervention which has been developed to treat those with Cluster B personality disorder (Davidson, 2000a). Patients are encouraged to engage in treatment through a formulation of their problems within a cognitive framework. Interventions focus on the patient’s beliefs and behavior that impair social and adaptive functioning. Thirty sessions of CBT over one year, each lasting up to one hour, are required to work on long-standing problems and develop new ways of thinking and behaving. Every effort is made to ensure that patients are encouraged to attend for all 30 sessions. If patients fail to attend a session of therapy, they are contacted by letter and telephone and given another appointment. We believe that less that 15 sessions may be an inadequate amount of therapy and indicative of nonengagement. Priority is given to behaviors that cause harm to self or others. Preliminary evidence using single case methodology suggested that this treatment is acceptable to patients and is effective in reducing self-harm and harm to others and in improving social functioning (Davidson & Tyrer, 1996). In addition, participants received the usual treatment they would have received if the trial had not been in place (see below for further information).

TREATMENT AS USUAL

All participants received the standard treatment they would have received if the trial had not been in place. Although standard treatment may vary across the three sites, and depend on the specific problems of the individual participant, it was thought that all participants would be in contact with mental health services and would have some contact with accident and emergency services for repeated self-harm episodes. TAU will be documented carefully after each patient exits the trial.

THERAPISTS

Five therapists provided CBT in the trial. Four were registered mental nurses and one, an occupational therapist. Three of the therapists had completed a 10-month CBT training course and had a certificate in cognitive therapy and one therapist had received CBT training in psychosis. Only one therapist had no previous training in CBT but had experience of managing individuals with personality disorder. The average age of therapists and number of years working in mental health services was 36 years (SD 6.8) and 12 years (SD 5.2) respectively. All therapists received three days initial training to socialize them to the specifics of the treatment model and received four further joint training days during the trial. All therapists received ongoing case supervision in their center throughout the trial on a fortnightly basis from an experienced CBT therapist. Providing the patient consented, therapists were required to audiotape a sample of CBT sessions from each patient to assess adherence to the therapy protocol and to allow the assessment of therapist competence using the Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale and, as CBT for personality disorders differs from traditional CBT, a specific rating scale for CBT for personality was also developed and piloted to assess overall adherence and competence in delivering treatment.

The Working Alliance Inventory (Tracey & Kokotovic, 1989) is completed by those receiving CBT and their therapists between sessions three and five of treatment to assess if working alliance is related to drop out from therapy and clinical outcome.

BASELINE AND OUTCOME MEASURES

Acts of deliberate self-harm in the twelve months prior to baseline are measured using a structured interview measure, the Acts of Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory (Davidson, 2000b). The aim of the inventory is to assess the frequency of attempts of both suicide and self-mutilation over a six month time period (12 months at baseline). In the inventory, suicidal acts and self-mutilation were recorded separately in chronological order. A suicidal act needed to meet all three of the following criteria: 1. deliberate (i.e. not be construed as an accident, there was planning involved, and the individual accepts ownership of the act, 2. life threatening, in that the individual’s life was deemed to be seriously at risk, or he or she thought it to be at risk, as a consequence of the act, and 3. the act resulted in medical intervention or intervention would have been warranted. The individual may have sought or would have warranted medical intervention or medical intervention was sought on their behalf. Medical intervention need not be treatment but at the minimum a physical examination is implied. An act of self-mutilation needed to satisfy the following criteria: 1. not a suicidal act as defined above, 2. deliberate (i.e., the act could not be construed as an accident and that the individual accepts ownership of the act, and 3. results in potential or actual tissue damage. If a patient reports self-harm events that occur within hours of each other (for example, scratching wrists or cigarette burning), these are to be considered as one event. Only when 24 hours has passed between events are they to be considered as separate acts. Inter-rater agreement on suicidal acts and acts of self-mutilation between two research assistants, where one interviewed a patient but the two assistants rated self-harm independently, was 100% (Cohen’s Kappa = 1) for both categories of self-harm on a sample of 12 patients.

Secondary outcome measures include the Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983), Beck Depression Inventory-II (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger, Gorsuch, & Lushene, 1970). Changes in social functioning are measured by the Social Functioning Questionnaire (Tyrer, 1990; Tyrer et al., 2004) and the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (Horowitz, Rosenberg, Baer, Ureno, & Villasenor, 1988), and changes in beliefs thought to be related to personality disorder are measured by the Schema Questionnaire (Young & Brown, 1990). The Euro-Qol (EQ-5D; the EuroQol Group, 1990) is used to measure health-related quality of life.

Trial participants are being assessed on all measures at six monthly intervals, except for the Schema Questionnaire and the Brief Symptom Inventory, where both are assessed at end of treatment and end of follow-up only. The research assistants on each site carry out all assessments and are blind to treatment group allocation. In addition, research assistants request that patients do not mention any details of any psychological treatment they may be receiving.

BLINDING

The research assistants responsible for the recording of outcomes were unaware of the treatment allocated or received. Therapists and research assistants were housed separately and did not knowingly come into contact with each other. Any unblinding of a research assistant to a patient’s treatment group is logged and another research assistant will follow-up that patient, where possible. At the end of the trial, data obtained by a research assistant who was unblinded will be informally compared with other data.

ECONOMIC EVALUATION

It is anticipated that the effectiveness of CBT may result in reductions in resource use and costs during follow-up of sufficient magnitude to offset the cost disadvantage compared to TAU alone. The primary objective of the economic analysis will be to estimate the total costs of health and social care, and other costs, from randomization to end of follow-up, and to estimate the relative cost-effectiveness of CBT plus TAU, in comparison with TAU alone, by combining the cost information with data on patients quality of life, assessed using the EQ-5D. The relative cost-effectiveness of CBT will be assessed by reference to the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), calculated as the incremental change in costs between the CBT and control group divided by the incremental change in quality of life. A cost-effectiveness acceptability curve will be used to incorporate the uncertainty around the sample estimates of mean costs and outcomes and uncertainty about the maximum or ceiling ICER that the decision maker would consider acceptable. The curve shows the probability that the data set are consistent with a true cost-effectiveness ratio falling below any particular ceiling ratio, based on the observed size and variance of the differences in both the costs and effects of the trial (Fenwick, Claxton, & Sculpher, 2001).

In the economic evaluation, a full assessment of direct and indirect costs is being made in both arms of the trial, including the cost of psychiatric, accident and emergency primary care, and social services using medical records and the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI; Knapp & Beecham, 1990). The number of emergency health service contacts and acts of deliberate self-harm will be sought from the patient for the 12 months prior to randomization and checked with medical records. Data on health services utilization during the trial will be collected directly from case notes at the end of the study. To maintain blindness, questions relating to health service use were omitted from the CSRI and this information collected from case notes at the end of the study. The CSRI was used to collect information on the current living arrangements and expenses of the client (including income, employment, and accommodation), together with questions about any use the client may have made of a range of social care and other services (e.g. social worker, voluntary agencies etc.). All the above measures were administered at baseline, prior to randomization and repeated at six monthly intervals for 24 months (6 and 12 months of treatment and at 6 and 12 months follow-up). All patients were assessed whether they completed treatment or not, provided consent was not withdrawn.

STATISTICAL ISSUES

Sample Size Considerations

The study was originally powered to detect an absolute difference of 35% at 2 years (1 year treatment phase, 1 additional year follow-up) after initiation of randomized treatment in the proportion of subjects with a primary outcome of any of 1. in-patient psychiatric hospitalization, 2. accident and emergency room contact, or 3. suicidal act. These three outcomes were chosen, a priori, because they represent both a personal and health burden. The data pertaining to these outcomes is also relatively easily obtained. There was uncertainty in the likely event rate at 24 months in the control group receiving TAU, so we considered rates of between 60% and 90%. With a total of n = 100 subjects randomized in equal proportion to CBT + TAU or TAU, and using a log rank test to compare the time to event curves in the two randomized groups, at a 5% level of significance, the study had 94% power (assuming a 60% control group proportion) and 96% power (assuming a 90% control group proportion). The study could tolerate a 35% loss to follow-up (reducing the effective sample size to 33 in each group) before the power reduced below the customary minimum requirement of 80% power. We can also address the issue of uptake of treatment. That is, it would be expected that not all subjects randomized to CBT will actually receive all the treatment sessions designed to yield the maximum treatment effect, leading to a potential dilution of the treatment effect. In practice we over recruited by 6%, randomizing n = 106 patients to the study. Assuming n = 53 randomized to each group, and assuming no loss to follow up, the study is powered at >80% to detect a smaller treatment of 25%. Combining these two effects of loss to follow up and dilution of treatment effect, the study would be powered at >80% to detect a 30% treatment effect assuming a 15% loss to follow up.

Monitoring

The study did not have a formal data and safety monitoring committee as there was felt to be no particular safety issues with the intervention under test (CBT plus TAU) and, with the steering committee monitoring study progress regularly using blinded data, the decision was for a fixed sample design with no sequential monitoring.

Outcomes and Statistical Analysis

The original primary analysis was a time to event analysis using a log rank test comparing the time spent without any of the 3 constituent outcomes, as listed above. It was felt by the steering committee that although event free duration was still an important goal of intervention, it did not address any potential reduction in the burden of outcomes—that is, the frequency with which these constituent outcomes occurred, and for what duration. We therefore changed the primary analysis to one based on a global test statistic as described by Tilley et al. (1999) following the work of Pocock, Geller, and Tsiatis (1987) and O’Brien (1984). This change was made without seeing any unblinded data. Since this change was made well after recruitment was over, with no prospect of additional recruitment, no power calculation on the new analysis has been done—however, it is our expectation that such an analysis will be at least as powerful as the original analysis, given that it incorporates additional information, albeit at the expense of the time to event. The actual power will depend on the correlation structure between the 3 constituent components of the primary outcome.

We have retained the time to event analysis as a secondary analysis, along with the 3 individual components of the primary outcome. Additional secondary outcomes include measures of mental state, social functioning, personality disorder, and quality of life (as listed previously), as well as other health service use data dealt with in the economic evaluation.

Comprehensive details of all the statistical analyses are documented in the Statistical Analysis Plan, agreed by the steering committee before any data is unblinded. All primary analyses will be according to the intention-to-treat principle. For subjects who withdrew from the study, consideration will be given to carrying forward their last recorded observations, and in the case of a subject with no post-randomization data, that would include their baseline data, in sensitivity analyses to explore the robustness of treatment effects to these missing data.

The primary analysis will be the composite outcome of the number of inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations, the number of accident and emergency room contacts, and the number of suicidal acts, using a global test statistic, at both 12 and 24 months post randomization. The secondary time to events analysis of time to first occurrence of any of the components of the primary outcome will compare the two treatment groups using a log rank test and the treatment effect estimated using a Cox proportional hazards model to adjust for the stratification factor and center and any baseline covariates considered to be of importance and pre-specified in the statistical analysis plan. The three primary outcomes will be considered together in the Cox model. Other secondary outcomes will be analyzed using techniques appropriate to the distribution of the data. Count data will be analyzed by χ2 tests or Fisher Exact tests, with adjustment for covariates via logistic regression. The continuous social, cognitive and mental health outcomes will be compared between the two groups using two sample t-tests with normal linear regression models to adjust treatment effects for covariates. Non-parametric methods such as Mann-Whitney test will be used if normal models appear inappropriate on inspection of the data.

Further analyses will be considered which attempt to estimate treatment effects to the observed levels of adherence to the study protocol, incorporating information on how many appointments were made and kept. Clearly there is the potential for bias to influence such analyses which incorporate post-randomization data as covariates, and this will be used primarily to support and better understand the results of the primary analyses based on intention to treat.

RESULTS

RECRUITMENT

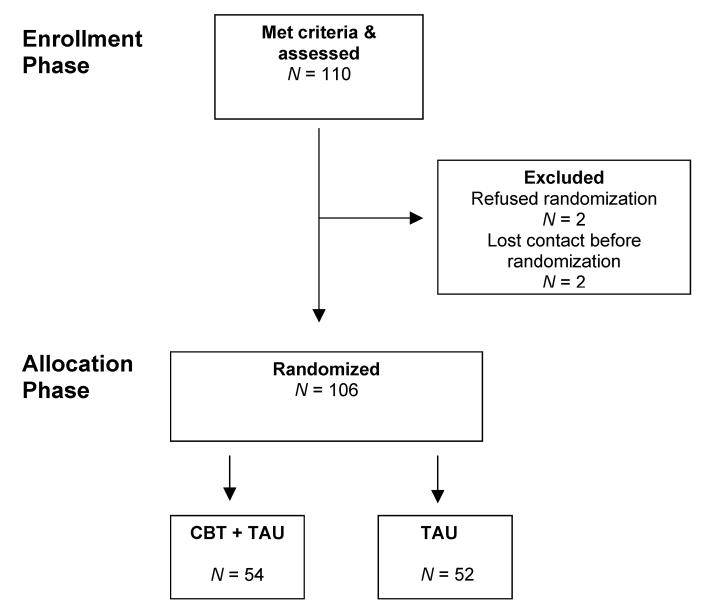

One hundred and twenty five patients were referred to the study. The rate of recruitment was steady over this time. Fifteen patients did not meet entry criteria. One hundred and ten patients met eligibility criteria. Of these, two refused to be randomized and a further two patients could not be contacted after initial assessment. One hundred and six patients were therefore randomized either to TAU, or CBT plus TAU. Forty-six patients were recruited from Glasgow, 42 from Ayrshire, and 18 from London. (See Figure 1 recruitment and randomization).

FIGURE 1.

Recruitment and randomization.

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

Baseline demographics and general clinical characteristics split by randomization group are given in Table 2. As one would expect in a randomized trial, the two groups were similar in respect to covariates at baseline.

TABLE 2.

Baseline Characteristics

| Baseline characteristics | TAU (N= 52) | TAU + CBT (N= 54) | Total (N= 106) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous variables | |||

| Age (years) | 31.4 (9.4), [18-52] | 32.4 (9.0), [19-57] | 31.9 (9.1), [18-57] |

| Days in psychiatric hospital in past 12 months | 25.6 (54.7), [0-334] | 22.8 (39.9), [0-181] | 24.2 (47.5), [0-334] |

| Age first DSH† (years) | 17.6 (8.2), [5-39] | 16.8 (7.1), [5-43] | 17.2 (7.6), 5-43] |

| Age first received mental health services (years) | 22.0 (8.5), [9-41] | 21.6 (7.7), [8-44] | 21.8 (8.1), [8-44] |

| Years since first DSH† | 13.8 (10.1), [1-47] | 15.6 (9.9), [1-48] | 14.7 (10.0), [1-48] |

| Categorical variables | |||

| Gender (female) | 44 (84.6) | 45 (83.3) | 89 (84.0) |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 45 (86.5) | 39 (72.2) | 84 (79.2) |

| Married | 5 (9.6) | 9 (16.7) | 14 (13.2) |

| Divorced | 2 (3.8) | 6 (11.1) | 8 (7.6) |

| Education level: | |||

| Postgraduate degree | 0 (0) | 3 (5.6) | 3 (2.8) |

| First Degree | 4 (7.7) | 3 (5.6) | 7 (6.6) |

| 1-3 years college training | 13 (25.0) | 17 (31.5) | 30 (28.3) |

| 5-6 years secondary school | 5 (9.6) | 4 (7.4) | 9 (8.5) |

| Left school at 16 years | 21 (40.4) | 20 (37.0) | 41 (38.7) |

| Other | 9 (17.3) | 7 (13.0) | 16 (15.1) |

| Special educational needs at school | 11 (21.2) | 8 (14.8) | 19 (17.9) |

| Ethnic—White | 52 (100) | 54 (100) | 106 (100) |

| Living alone | 14 (26.9) | 24 (44.4) | 38 (35.8) |

| Unemployed | 35 (67.3) | 37 (68.5) | 72 (67.9) |

| Any benefits | 42 (80.7) | 47 (87.0) | 89 (84.0) |

| Involved with any legal/law enforcement services during last 6 months | 23 (44.2) | 27 (50.0) | 50 (47.2) |

Note. Data shown are mean (SD), range for continuous variables and number (%) for categorical variables.

Deliberate self-harm.

The study group is characterized as having an average age of 32 years, 84% female, 80% never married, about half leaving secondary school at 16 years old and all of White ethnicity. The mean (SD) time spent in psychiatric hospital in the 12 months prior to baseline was 24.2 (47.5) days and the average (SD) number of years since first act of deliberate self-harm (DSH) was 14.8 (10.0) years. Just under a half of the sample (47%) had contact with legal or law enforcement agencies in the six months prior to randomization. Overall, 36% of subjects were reported as living alone, 68% were unemployed, and 84% were receiving benefits, with around half of these receiving a severe disablement allowance.

Across centers (data not shown in Table 2) the participants were also broadly similar, although in London more males were recruited; 28% (5/18) compared to 17% (8/46) in Glasgow and 10% (4/42) in Ayrshire, and participants are on average 7 years older (37 years compared to 30 years in Glasgow and Ayrshire). There were some noticeable differences between sites in unemployment with less than 50% (21/46) of subjects in Glasgow unemployed at baseline compared to 88% (37/42) and 78% (14/18) in Ayrshire and London respectively. In addition, a higher proportion of participants in London lived alone and had been involved with legal/law enforcement services during last 6 months.

PSYCHOMETRIC MEASURES

Table 3 reports the baseline scores for the psychometric measures. For all psychometric tests, other than the EuroQol thermometer a higher score reflects a more maladaptive, unhealthy, or depressive state. The mean scores for the psychometric measures were broadly similar in all three centers and indicated severe levels of depression (Beck et al., 1996) and anxiety, moderate to high symptoms on the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) and high levels of interpersonal distress relative to the general population. For Young’s Schema Questionnaire (YSQ), the mean overall score (total score/75) and mean score for each of the 15 sub-scales (total score/5) is given instead of the sum. Inspection of average scores for the group as a whole on the YSQ shows relatively high scores on the dimensions of mistrust and abuse, fears of abandonment and social isolation, and lower scores on the entitlement dimension. In the case of the EuroQol the higher the score the better the participant felt their health status was that day. It is interesting to note that on average those in London reported their health status on the EuroQol thermometer at baseline to be better than participants in Glasgow and Ayrshire: mean 53.9 (SD 25.5) compared to 39.8 (21.5) and 47.3 (21.6).

TABLE 3.

Measures of Mood, Psychiatric Symptoms, Social & Interpersonal Functioning, and Beliefs at Baseline

| Psychometric measures | TAU (N= 52) |

TAU + CBT (N= 54) |

Total (N= 106) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BDI-II—Total Score (max = 63) | 42.5(12.3) | 42.6(10.1) | 42.5(11.2) |

| BSI—Global Severity Index (GSI) | 2.4(0.9) | 2.6(0.6) | 2.5(0.8) |

| EuroQol—Thermometer (max = 100) | 48.4(23.9) | 42.0(21.1) | 45.1(22.6) |

| EuroQol—Weighted Health State Value | 0.52(0.36) | 0.49(0.37) | 0.50(0.36) |

| IIP-32—Total Score (max = 128) | 65.9(17.4) | 72.4(16.0) | 69.2(17.0) |

| SFQ—Total Score (max = 24) | 14.3(4.1) | 14.9(4.1) | 14.6(3.9) |

| State-Anxiety Scale (max = 80) | 51.4(12.0) | 53.6(12.2) | 52.5(12.1) |

| Trait-Anxiety Scale (max = 80) | 64.0(8.6) | 65.8(7.8) | 64.9(8.2) |

| Young Schema Questionnaire | |||

| Total Mean Score | 3.78(0.70) | 4.13(0.66) | 3.96(0.70) |

| Emotional Deprivation | 3.82(1.53) | 4.53(1.17) | 4.18(1.40) |

| Abandonment | 4.37(1.55) | 4.63(1.26) | 4.50(1.41) |

| Mistrust/Abuse | 4.46(1.38) | 4.84(1.04) | 4.65(1.23) |

| Social Isolation | 4.32(1.40) | 4.84(1.04) | 4.59(1.25) |

| Defectiveness/Shame | 4.16(1.15) | 4.40(1.08) | 4.28(1.12) |

| Failure | 4.16(1.56) | 4.34(1.58) | 4.25(1.57) |

| Dependence/Incompetence | 3.55(1.18) | 3.92(1.27) | 3.74(1.24) |

| Vulnerability to Harm & Illness | 3.89(1.29) | 4.06(1.31) | 3.98(1.30) |

| Enmeshment | 2.35(1.32) | 2.57(1.59) | 2.46(1.46) |

| Subjugation | 4.02(1.33) | 4.30(1.19) | 4.16(1.26) |

| Self Sacrifice | 3.80(1.38) | 4.10(1.41) | 3.95(1.40) |

| Emotional Inhibition | 3.49(1.39) | 3.98(1.41) | 3.74(1.41) |

| Unrelenting Standards | 3.93(1.43) | 4.01(1.36) | 3.97(1.39) |

| Entitlement | 2.33(1.05) | 3.02(1.24) | 2.68(1.19) |

| Insufficient Self-Control/Self- Discipline | 4.06(1.36) | 4.42(1.32) | 4.24(1.35) |

Note. Data are shown as mean (SD).

ACTS OF DELIBERATE SELF-HARM

Suicide attempts and acts of self-mutilation in the twelve months prior to randomization are summarized in Table 4. Seventy-five (71%) participants had at least one suicidal act (ranging from 1–12) in the 12 months prior to randomization and 99 (93%) of participants had at least one act of self-mutilation (ranging from 1–365). The most common parasuicidal method was overdose, with 61 participants attempting at least one overdose. Self-laceration, and overdose plus self-laceration, were the next two most frequently used methods. A lower percentage of London participants had at least one suicidal act in the previous 12 months: 61% (11/18) compared to 72% (33/46) for Glasgow and 74% (31/42) for Ayrshire.

TABLE 4.

Participants with Suicide Attempts and Acts of Self-Mutilation 12 Months Prior to Baseline

| Act | TAU (N= 52) | TAU + CBT(N= 54) | Total (N= 106) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide attempts (total)† | 37 (71.2) | 38 (70.4) | 75 (70.8) |

| Method: | |||

| Overdose | 29 (55.8) | 32 (59.3) | 61 (57.5) |

| Self-laceration | 6 (11.5) | 8 (14.8) | 14 (13.2) |

| Burning | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (0.9) |

| Swallowing sharp objects | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Hanging | 3 (5.8) | 4 (7.4) | 7 (6.6) |

| Shooting | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Jumping from height or under train | 4 (7.7) | 1 (1.9) | 5 (4.7) |

| Car exhaust fumes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Overdose & self-laceration | 8 (15.4) | 2 (3.7) | 10 (9.4) |

| Overdose & jumping | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (0.9) |

| Other | 5 (9.6) | 7 (13.0) | 12 (11.3) |

| Self mutilation‡ | 49 (94.2) | 50 (92.6) | 99 (93.4) |

Note. Data are presented as number (%).

For patients with at least one suicidal attempt. The median number of suicide attempts was 2 (range 1-12).

For those with at least one act of self-mutilation. The median number of acts of self mutilation was 13 (range 1-365).

DISCUSSION

This paper describes the rationale for a randomized controlled trial of individual cognitive behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder. We describe our study sample and methods, and record our primary and secondary hypotheses and plan for data analysis. The characteristics of the study sample suggest severe personality disturbance. Over seventy percent of the sample reported having at least one suicidal act in the 12 months before entry into the study and over ninety percent of participants reported self-mutilation. The average number of days in psychiatric hospital was 24 with at least one individual having spent all of the previous 12 month period in hospital. The average age at which self-harm had started was 17, though formal help had not been sought until the age of 21. The sample is also characterized by being mostly women, single, of white ethnicity, relatively poor educational achievement, on social security benefit, and with half the sample having some recent involvement with law enforcement. They report high levels of depression, anxiety, and interpersonal distress.

Of the six studies to date, a reduction in the frequency of suicidal acts has been a consistently measured outcome, even if not always the primary outcome of interest or required as an entry criteria of the study (see Table 1). A variety of different semi-structured interviews have been used to assess suicidal acts. Self-mutilation has also been assessed in most studies but usually if the mutilation required medical attention or treatment, indicating a relatively severe level of self-harm. We intend to report on self-reported levels of self-mutilation, whether this required medical attention or not, and suicidal acts at end of treatment and at follow-up as these behaviors result in different clinical outcomes and may differ on a number of psychological characteristics and functions that are yet to be more fully understood.

The trial described here has attempted to improve on methodological weaknesses of the previous randomized controlled trials for individuals with borderline personality disorder. The trial is multi-center, randomization procedures are specified and carried out off-site, the primary and secondary outcomes are declared at the outset, and the research assistants are blind to patient treatment allocation. The sample is satisfactory in terms of power and highly representative in terms of the patients referred to the trial (96% of patients meeting criteria were randomized), and involves both male and female participants. Only one mode of treatment is delivered in the experimental arm, and usual treatment is balanced between both arms of the trial. Therapist competency is assessed by recording audiotapes of sessions. A statistical analysis plan is declared before any data are unblinded. In addition, the cost effectiveness of the intervention will be fully assessed.

Footnotes

The research is supported by a grant from the Wellcome Trust, UK. Reference 064027/Z01/Z.

REFERENCES

- Bateman A, Fonagy P. Effectiveness of partial hospitalization in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:1563–1569. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.10.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman AW, Fonagy P. Treatment of borderline personality disorder with psychoanalytically oriented partial hospitalisation: An 18 month follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:36–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman AW, Fonagy P. Mentalization-based treatment of BPD. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2004;18:36–51. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.1.36.32772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Freeman A. Cognitive therapy of personality disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GK, Newman CF, Charlesworth SE, Crits-Christoph P, Beck AT. An open trial of cognitive therapy for borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorder. 2004;18:257–271. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.3.257.35450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkin J, Widiger T, Frances A, Hurt SW, Gilmore M. Prototypic typology and the borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1983;92:263–275. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.92.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson KM. Cognitive therapy for personality disorders: A guide for clinicians. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann Press; 2000a. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson KM. Acts of deliberate self-harm inventory. 2000b. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson K, Scott J, Schmidt U, Tata P, Thornton S, Tyrer P. Therapist competence and clinical outcome in the Prevention of Parasuicide by Manual Assisted Cognitive Behavior Therapy Trial: The POPMACT study. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:855–863. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson KM, Tyrer P. Cognitive therapy for antisocial and borderline personality disorders: Single case series. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1996;35:413–429. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1996.tb01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine. 1983;13:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The EuroQol Group EuroQol: A new facility for the measurement of healthrelated quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans K, Tyrer P, Catalan J, Schmidt U, Davidson K, Dent J, et al. Manual-assisted cognitive behavior therapy (MACT): A randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention with bibliotherapy in the treatment of recurrent deliberate self-harm. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29:19–25. doi: 10.1017/s003329179800765x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenwick E, Claxton K, Sculpher M. Representing uncertainty: The role of cost-effectiveness acceptability curves. Health Economics. 2001;10:779–789. doi: 10.1002/hec.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Benjamin LS. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for Axis I DSM-IV disorders—Patient Edition (with psychotic screening) SCID-I/P (W/ psychotic screen) (version 2) New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz LM, Rosenberg SE, Baer BA, Ureno G, Villasenor VS. Inventory of Interpersonal Problems: Psychometric properties and clinical applications. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:885–892. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernberg OF. A psychoanalytic theory of personality disorder. In: Clarkin JF, Lenzenweger M, editors. Major theories of personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. pp. 106–137. [Google Scholar]

- Koons CR, Robins CJ, Tweed JL, Lynch TR, Gonzalez AM, Morse JQ, et al. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy in women veterans with borderline personality disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2001;32:371–390. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp M, Beecham J. Costing mental health services: The client services receipt inventory. Psychological Medicine. 1990;20:893–908. doi: 10.1017/s003329170003659x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieb K, Zanarini MC, Schmahl C, Linehan MM, Bohus M. Borderline personality disorder. Lancet. 2004;364:453–461. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16770-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Tuket DA, Heard HL, Armstrong HE. Interpersonal outcome of cognitive behavioral treatment for chronically suicidal borderline patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1771–1776. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.12.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, Allmon D, Heard HL. Cognitive behavioural treatment for chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:1060–1064. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360024003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Heard HL, Armstrong HE. Naturalistic follow-up of a behavioural treatment for chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:971–974. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240055007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlum L, Friis S, Vaglum P, Karterud S. The longitudinal pattern of suicidal behaviour in borderline personality disorder: A prospective follow-up study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1994;90:124–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, for the CONSORT Group The CONSORT statement: Revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet. 2001;357:1191–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munroe-Blum H, Marziali E. A controlled trial of short-term group treatment of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorder. 1995;9:190–198. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien PC. Procedures for comparing samples with multiple endpoints. Biometrics. 1984;40:1079–1087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock SJ, Geller NJ, Tsiatis AA. The analysis of multiple endpoints in clinical trials. Biometric. 1987;43:487–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C, Gorsuch R, Lushene R. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Tilley BC, Pillemer SR, Heyse SP, Li S, Clegg DO, Alarcon GS. Global statistical tests for comparing multiple outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis trials. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1999;42:9–1879. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199909)42:9<1879::AID-ANR12>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracey TJ, Kokotovic AM. Factor Structure of the Working Alliance Inventory. Psychological Assessment. 1989;1:207–210. [Google Scholar]

- Turner RM. Naturalistic evaluation of dialectical behavior therapy-oriented treatment for borderline personality disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2000;7:413–419. [Google Scholar]

- Tyrer P. Social Functioning Questionnaire. Personality disorder and social functioning. In: Peck DF, Shapiro CM, editors. Measuring human problems: A practical guide. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons; 1990. pp. 136–137. [Google Scholar]

- Tyrer P, Nur U, Crawford M, Karlsen S, McLean C, Rao B, Johnson T. Social Functioning Questionnaire: A rapid and robust measure of perceived functioning. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheul R, van den Bosch LMC, Koeter WJ, de Ridder MA, Stijnen T, van den Brink W. Dialectical behavior therapy with women with borderline personality disorder. 12-month, randomised clinical trial in the Netherlands. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;182:135–140. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger RJ, Gunderson JG. Completed psychotherapies with borderline patients. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 1984;38:190–202. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1984.38.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JE, Brown G. Young Schema Questionnaire. In: Young JE, editor. Cognitive therapy for personality disorders: A schema-focused approach. 3rd ed. Professional Resource Exchange, Inc.; 1990. (1999) [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Silk KR. Mental health service utilization by borderline personality disorder patients and Axis II comparison subjects prospectively followed up for 6 years. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:28–36. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]