Abstract

Background:

The use of invasive procedures has mostly been studied in retrospective (multi)- national registries. Limited evidence exists on the association between microalbuminuria and coronary artery disease (CAD).

Methods:

The incidence of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) and invasive cardiac procedures was registered between 1997 and 2003 in 8139 subjects, without prior documented CAD, in the PREVEND cohort study (the Netherlands), in which the focus is on microalbuminuria and cardiovascular risk. Qualitative coronary angiographic analysis was performed.

Results:

During 5.5 years of follow-up, a first MACE occurred in 271 (3.3%) and a first coronary angiography (CAG) was performed in 264 (3.2%) subjects. Of these, 216 CAGs were available for qualitative angiographic analysis. Indications for CAG were stable angina in 129, acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in 55 and ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in 32 subjects. Obstructive coronary artery disease was present in 61, 53 and 30 subjects, respectively. A revascularisation was performed in 50 (39%), 50 (91%) and 25 (78%) subjects, respectively. Microalbuminuria was associated with a first MACE, after adjustment for established risk factors. Microalbuminuria was present at baseline in 9% of subjects with normal coronary arteries, in 21% of subjects with one- and two-vessel CAD and in 39% of subjects with threevessel or left main CAD at CAG during follow-up (Ptrend=0.005).

Conclusion:

This large cohort study shows that two-thirds of diagnostic CAGs for stable angina were not followed by a revascularisation, in contrast to CAGs for STEMI or ACS. Furthermore, this study shows that microalbuminuria is associated with CAD. (Neth Heart J 2007;15:133-41.)

Keywords: coronary angiography, revascularisation, major adverse cardiac events, MACE, coronary artery disease, microalbuminuria

Most of our knowledge related to the incidence and consequences of invasive procedures in patients with suspected coronary artery disease (CAD) is derived from large (multi)national registries or randomised controlled trials, with a retrospective design and selection of participating hospitals or patient groups. These registries have shown that the increase in numbers of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) has been almost twice the increase in the number of coronary angiographies (CAG).1 In spite of this increase, an underuse of coronary revascularisations has been reported in appropriate candidates for a revascularisation procedure.1-3 Furthermore, it has been shown that up to 50% or more of CAGs are not followed by a revascularisation procedure.1,4

A prospective cohort analysis may provide additional information, since it allows insight into baseline clinical variables and the assessment of events and procedures in patients with suspected CAD, reflecting routine clinical practice. We therefore performed an additional analysis of the prospective Prevention of REnal and Vascular ENdstage Disease (PREVEND) cohort study, in which the focus is on microalbuminuria and cardiovascular risk in the general population, to assess the number of invasive procedures following major adverse cardiac events (MACE). Our second purpose was to assess the indications for CAGs and the incidence of subsequent revascularisation procedures in subjects with suspected CAD. Thirdly, we assessed the association between microalbuminuria and CAD.

Methods

Study population

The principle purpose of the PREVEND study is to assess the value of microalbuminuria in relation to cardiovascular and renal risk in the general population. During the period 1997 to 1998, all inhabitants of the city of Groningen, the Netherlands aged between 28 and 75 years were asked to answer a short questionnaire and to send in a morning urine sample. Insulin treatment and pregnancy were exclusion criteria. Altogether 40,856 subjects responded. All subjects with a morning urinary albumin concentration ≥10 mg/l (n=7768) and a random sample of subjects with a morning urinary albumin concentration <10 mg/l were invited to an outpatient clinic. The screening programme was completed by 8592 subjects, including 6000 subjects with and 2592 subjects without an elevated morning urinary albumin concentration. Collected baseline data at the outpatient clinic included medical history, demographics, biometric data, urine and blood collections and laboratory measurements. For the current analysis, only subjects without prior documented CAD were included. Prior documented CAD was defined as a history of myocardial infarction, revascularisation procedure or obstructive coronary artery disease prior to inclusion in the PREVEND study. A history of myocardial infarction was based on a subject’s medical history, including structured questionnaire, and the information on previous CAD was complemented by review of the medical report. In table 1, baseline demographics and laboratory parameters from the baseline visit of the PREVEND cohort are given. For details on the PREVEND study design we refer to earlier publications.5 The PREVEND study was approved by the medical ethics committee and conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the declaration of Helsinki. All subjects gave written informed consent.

Definition of endpoints and follow-up

Cardiac events and revascularisation procedures during follow-up were counted in PREVEND subjects without prior documented CAD at baseline. The endpoint of this study was defined as cardiovascular death (ICD- 10 I01-99), cardiac events (ICD-9 410, 411), PCI and coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG). The vital status of all subjects was evaluated through the municipal register until 31 December 2003. Causes of death were obtained from the Central Bureau of Statistics according to ICD-10 codes (I01-I99 for cardiovascular disorders). Information related to cardiac events and revascularisation procedures was obtained from the national hospital information system (Prismant, Utrecht, the Netherlands). Cardiac events were reviewed by a clinical event committee and divided into ST-elevation myocardial infarctions (STEMI) or non- ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes (ACS). STelevation myocardial infarction was defined as chest pain and ST elevation >1 mm in at least two contiguous leads.6 To evaluate therapeutic consequences after STEMI, subjects with STEMI were divided into those presenting within or over 24 hours after the onset of chest pain. Non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome was defined as chest pain with positive cardiac markers (troponin or creatinine kinase) and/or dynamic STsegment changes.7 Major adverse cardiac event was defined as cardiovascular death, STEMI, ACS or revascularisation procedure.

Assessment of coronary angiography

The incidence of coronary angiographies was obtained from the Catheterisation Laboratory registries of the two hospitals in the Groningen region, namely the University Medical Centre Groningen (UMCG) and the Martini Hospital Groningen (MHG) and was completed with information on CAG obtained from the national hospital information system (Prismant, Utrecht, the Netherlands). If a PCI was performed during the same session as the CAG, PCI and CAG were counted as separate procedures. All CAGs performed in the UMCG or MHG were requested in order to perform qualitative angiographic analysis and to evaluate the therapeutic consequences as decided by the UMCG Thoraxcentre multidisciplinary team. The UMCG Thoraxcentre multidisciplinary team makes the decisions regarding performing revascularisation procedures or continuing conservative treatment for all subjects in whom CAG is performed in the UMCG or MHG. The team has extensive experience with the RAND-UCLA criteria8,9 and bases its decisions on the European Society of Cardiology guidelines. 10 Indications for CAG were divided into STEMI presenting within or over 24 hours after the onset of chest pain, ACS or stable angina. Stable angina was defined as angina or angina-like symptoms. Indications for CAG and peri- and post-procedural events were reviewed by a senior cardiologist.

Qualitative angiographic analysis

We performed qualitative angiographic analysis of all available first CAGs for all indications (STEMI, ACS or stable angina). Qualitative coronary angiographic analysis was performed by a senior cardiologist (RT), who had no knowledge of the clinical indications for CAG or of the subjects’ clinical status. Analysis of CAGs included the identification of obstructive lesions (≥50% stenosis) or minor lesions (<50% stenosis) in the left main stem, left anterior descending artery, left circumflex artery and/or right coronary artery. If an obstructive lesion was found in a coronary vessel, additional minor lesions present in this vessel were not recorded. When no lesions were found, the coronary arteries were graded as normal. An interobserver agreement of 95% was found in a random sample of 44 coronary angiographies (20%) which were analysed by a senior cardiologist (FZ) unaware of the prior analyses.

Data handling and definitions

Risk factors were defined as follows or as given in the tables. Hypertension was defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg or use of antihypertensive medication. Hypercholesterolaemia was defined as total cholesterol >6.5 mmol/l or use of lipid-lowering treatment. Abdominal obesity was defined a waist circumference ≥102 cm in men and ≥88 cm in women.11 Low HDL cholesterol was defined as HDL cholesterol <1.04 mmol/l in men and <1.30 mmol/l in women.11 Diabetes was defined as fasting plasma glucose levels >6.9 mmol/l, or non-fasting plasma glucose levels >11.0 mmol/l or the use of oral antidiabetic drugs.12 High age was defined as age >60 years. High hs-Creactive protein (CRP) was defined as hs-CRP >3.0 mg/l.13

Analytical methods

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure measurements were calculated as the mean of the last two out of ten consecutive measurements with an automatic Dinamap XL model 9300 series device (Johnson-Johnson Medical INC, Tampa, Florida). Serum total cholesterol was determined by Kodak Ektachem dry chemistry (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, New York, USA). HDL cholesterol was determined by MEGA (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The urinary albumin excretion was measured as the mean of two 24-hour urine collections. Urinary albumin concentrations were determined by nephelometry with a threshold of 2.3 mg l-1 and intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation of less than 2.2 and 2.6%, respectively (Dade Behring Diagnostic, Marburg, Germany). High-sensitive CRP was measured by nephelometry with a threshold of 0.18 mg/l and intra- and interassay coefficients of variation of <4.4 and <5.7% respectively (BNII, Dade Behring Diagnostic, Marburg, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are given as means (standard deviation). In case of a skewed distribution, the median (interquartile range) was used. Differences between groups were evaluated by Χ2 tests, when appropriate. P values were two-sided and needed to be <0.05 to be significant. Probability-weighted Cox proportional hazard analyses were performed to adjust for the survey weights based on nonrandom inclusion of subjects with and without elevated morning urinary albumin concentration levels at the PREVEND cohort study entry. Models were fitted to evaluate the univariate impact of microalbuminuria, and after adjustment for age and sex, and after adjustment for established risk measures, namely smoking status, diabetes, obesity, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, low HDL cholesterol and high hs-CRP. Event-free survival time for subjects was defined as the period from the date of the outpatient clinic baseline assessment to the date of first MACE or CAG, or death from any cause until 31 December 2003, or 31 December 2002 until the date that follow-up information was available regarding specific causes of death. If a person had moved away from the city of Groningen or to an unknown destination, or died due to a noncardiovascular cause, the person was censored on the last available contact date or date of death. All calculations were performed with SPSS version 11.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of the initial 8592 subjects included, 8139 had no prior documented CAD (94.7%), and were included in the current analysis. The population consisted of middle-aged subjects and included an equal number of males and females. More than one third were current smokers and only a small number had diabetes (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 8139 PREVEND participants without prior documented CAD.

| Characteristics | n=8139 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 49 | (12) |

| Male gender, no. (%) | 3979 | (49) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) kg/m2 | 26 | (4) |

| Blood pressure, mean (SD), mmHg | ||

| - Systolic | 129 | (20) |

| - Diastolic | 74 | (10) |

| Smoking status, no. (%) | ||

| - Current | 2786 | (34) |

| - Past | 2880 | (35) |

| Diabetes, no. (%) | 270 | (3) |

| Cholesterol, mean (SD), mmol/l | ||

| - Total | 5.6 | (1.1) |

| - HDL | 1.33 | (0.40) |

| Albuminuria, median (interquartile range), mg/24 h | 9.17 | (6.24-16.88) |

| hs-CRP, median (interquartile range), mg/l | 1.24 | (0.54-2.87) |

| Medication, no. (%) | ||

| - Lipid-lowering | 875 | (5) |

| - Antihypertensive | 389 | (11) |

CAD=coronary artery disease, hs-CRP=high sensitivity C-reactive protein, HDL=high density lipoprotein. SI conversion factor: to convert mmol/l to mg/dl, multiply values for total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol by 38.6.

Incidence of MACE

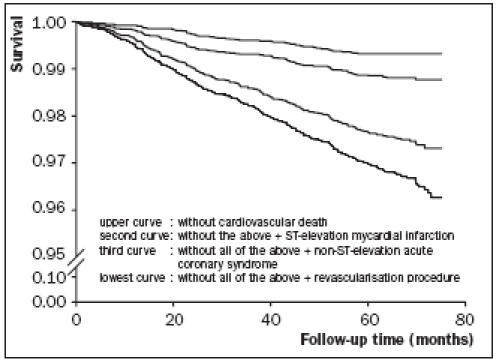

During a mean of 5.5 years of follow-up, 271 subjects (3.3%) experienced a first MACE. During follow-up, 747 subjects (9%) left the area and 186 subjects (2%) died from a noncardiovascular cause and were therefore censored. Incidence of all and first MACEs, respectively, are shown in table 2. Kaplan Meier survival curves for subjects who remained free from cardiovascular death, STEMI, ACS or revascularisation procedures show a gradual decrease in event-free survival (figure 1).

Table 2.

Incidence of MACE in 8139 PREVEND participants without prior documented CAD (1997-2003).

| Outcome | All events | First events |

|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Major adverse cardiac event | 419† (5.1) | 271‡ (3.3) |

| - Revascularisation procedure | 181 (2.2) | 70 (0.9) |

| - Percutaneous coronary intervention | 115 (1.4) | 40 (0.5) |

| - Coronary artery bypass surgery | 66 (0.8) | 30 (0.5) |

| - Non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome | 133 (1.6) | 118 (1.4) |

| - STEMI, time delay after onset of chest pain | 51 (0.6) | 50 (0.6) |

| - <24 hours | 38 (0.5) | 37 (0.5) |

| - >24 hours | 13 (0.2) | 13 (0.2) |

| - Cardiovascular mortality | 54 (0.7) | 33 (0.4) |

MACE=major adverse cardiac event, CAD=coronary artery disease, STEMI=ST-elevation myocardial infarction. MACE is defined as a composite endpoint comprising, respectively, any (†) and the first of any (‡) of these events: revascularisation procedure, non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome, ST-elevation myocardial infarction, or cardiovascular death.

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier survival curves of 8139 PREVEND subjects without prior documented CAD who remained free from cardiovascular death, ST-elevation myocardial infarction, non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome, or revascularisation procedure.

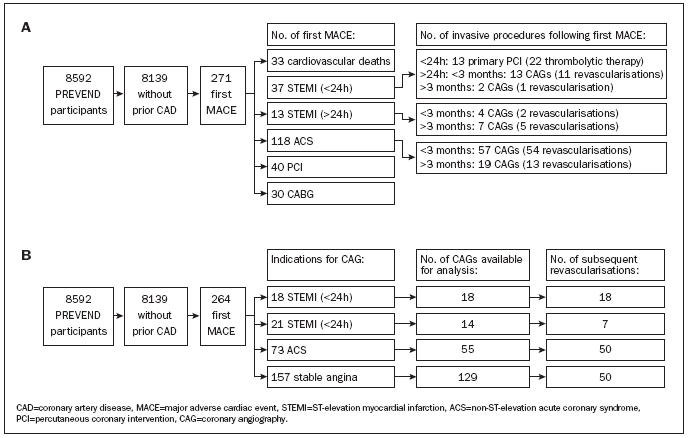

Number of invasive procedures following a first MACE

The number of invasive procedures and therapeutic consequences after a first MACE is shown in figure 2A (flowchart). Of the 50 patients presenting with STEMI as a first cardiac event, 37 subjects presented within 24 hours after onset of symptoms. Twenty-two of these subjects (59%) received thrombolytic therapy. In two subjects (5%) contraindications for thrombolytic therapy were present, but primary PCI was not performed. Primary PCI was carried out in 13 subjects (35%).

Of the 118 subjects with ACS, in 57 subjects (48%) CAG was performed within three months, which was followed by a revascularisation procedure in 54 subjects (46%). At a later stadium, more invasive procedures were performed in an additional number of subjects. This resulted in a total of 76 CAGs (64%) and 67 revascularisation procedures (57%), including 45 PCIs (38%) and 32 CABGs (27%), during the entire followup period.

Incidence of coronary angiographies

In total, 264 subjects (3.2%) underwent a first CAG after inclusion in the PREVEND study (incidence 0.6% per year). In 48 subjects (18.2%) this was followed by a second CAG (incidence 0.1% per year). The incidence of CAGs was stable during follow-up (data not shown). Indications for 264 first CAGs were STEMI in 39 subjects (15%), following an ACS in 73 subjects (28%) and stable angina in 152 subjects (58%), respectively, as shown in figure 2B (flowchart).

Figure 2.

Flow chart for the incidence of first MACE and subsequent invasive procedures (A) and for the incidence and indications of first coronary angiographies and subsequent revascularisation procedures (B).

Coronary angiographic findings and subsequent revascularisation procedures

Of 264 first CAGs, 240 CAGs were performed in the UMCG or MHG and 216 of these were available for angiographic analysis (90%). The angiographic findings and revascularisation procedures following these 216 first CAGs, according to indications, are given in table 3.

Table 3.

Indications and findings of first CAG in 216 PREVEND participants without prior documented CAD in whom CAG was available for analysis.

| N | Normal coronary arteries | Nonobstructive CAD | One-vessel CAD | Two-vessel CAD | Three-vessel CAD or LM lesion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STEMI (<24 h) | 18 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 11 | (61) | 5 | (28) | 2 | (11) |

| STEMI (>24 h) | 14 | 1 | (8) | 1 | (8) | 6 | (46) | 6 | (39) | 0 | (0) |

| ACS | 55 | 0 | (0) | 2 | (4) | 24 | (44) | 16 | (29) | 13 | (24) |

| Stable angina* | 129 | 34 | (26) | 34 | (26) | 21 | (16) | 23 | (18) | 17 | (13) |

ACS=non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome, CAD=coronary artery disease, CAG=coronary angiography, STEMI=ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

* Stable angina is defined as angina or angina-like symptoms.

Of 129 subjects with a first CAG for stable angina, 61 subjects had obstructive CAD, while in 68 subjects normal coronary arteries or nonobstructive coronary artery disease were present. Of 61 subjects with obstructive CAD, a revascularisation procedure was performed in 50 subjects, while in 11 subjects conservative treatment was continued (due to a coronary anatomy not suitable for intervention in nine subjects, and angina being secondary to other causes in two subjects). Of 68 subjects without obstructive CAD, reasons for CAG were the evaluation of aortic valve disease, atrial septum defect or electrophysiology in 13 subjects. All subjects had angina or angina-like symptoms. In 26 subjects a CAG was performed because of stable angina, without evidence of ischaemia based on electrocardiographic exercise testing or myocardial perfusion imaging, in order to eliminate diagnostic uncertainty. In 15 subjects an abnormal electrocardiographic exercise test result and in 14 subjects a reversible myocardial perfusion defect were the reasons to perform CAG.

All subjects who underwent acute CAG for STEMI <24 hours had obstructive CAD and were treated with primary PCI. Of the 14 subjects in whom a CAG was performed for STEMI >24 hours, 12 were found to have CAD, and this followed by a revascularisation procedure in seven and conservative treatment in five subjects.

Obstructive CAD was found in 53 out of 55 subjects with a first CAG following an ACS. In 50 out of these 55 subjects (91%) a subsequent revascularisation procedure was performed. In three subjects with obstructive CAD, a revascularisation procedure was not indicated and conservative treatment was continued.

Association between microalbuminuria and CAD

The association between microalbuminuria and the occurrence of a first MACE during follow-up is shown in table 4. In univariate analysis and after adjustment for established coronary risk factors, microalbuminuria was associated with a first MACE.

Table 4.

Risk of a first MACE in 8139 PREVEND participants without prior documented CAD according to the presence of microalbuminuria.*

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

| Microalbuminuria | 3.03 (2.68-3.43) | 1.83 (1.60-2.08) | 1.24 (1.06-1.45) |

CI=confidence interval, HR=hazard ratio, MACE=major adverse cardiac event. *Microalbuminuria is defined as urinary albumin excretion levels >30 mg/24h.

Model 1 includes microalbuminuria. Model 2 includes microalbuminuria, age and sex. Model 3 includes microalbuminuria, age, sex, smoking, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolaemia, low HDL cholesterol, and elevated hs-CRP levels. For definitions please see the methods section.

As shown in table 5, microalbuminuria was present at baseline in 9% of subjects with normal coronary arteries, in 21% of subjects with one- and two-vessel CAD and in 39% of subjects with three-vessel or left main CAD at CAG during follow-up (Ptrend=0.005).

Table 5.

Severity of CAD at CAG according to the presence of microalbuminuria at baseline of the PREVEND cohort study.*

| Normal coronary arteries | Nonobstructive, 1- or 2-vessel CAD | 3-vessel or left main CAD | Ptrend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=32 | n=143 | n=31 | ||

| Normoalbuminuria, n (%) | 29 (91) | 113 (79) | 19 (61) | 0.005 |

| Microalbuminuria, n (%) | 3 (9) | 30 (21) | 12 (39) |

*In 206 subjects in whom CAG and urinary albumin excretion levels were available. Microalbuminuria was defined as urinary albumin excretion >30 mg/24h.

CAD=coronary artery disease, CAG=coronary angiography.

Discussion

This is the first report to describe the clinical and angiographic characteristics of subjects without a history of CAD undergoing a first CAG after inclusion in a prospective population-based cohort study. We performed the current analysis since most of the insight into the incidence of CAGs and revascularisation procedures results from registries with a retrospective design. This type of study uses a selection of hospitals and subject groups. A prospective cohort analysis has major advantages, since it allows insight into baseline clinical variables and the assessment of events and procedures in subjects with suspected CAD, reflecting routine clinical practice.

Invasive procedures after a first MACE

The low number of primary PCIs in subjects with STEMI, namely in only one-third, reflects the clinical practice between 1997 and 2003, because at this time thrombolytic therapy was still accepted as first-line treatment in these subjects. This number will have increased since then, as primary PCI has been accepted as a first-line treatment in subjects presenting with STEMI.14 The number of CAGs in subjects with ACS (48% within three months, 64% during total follow-up) was in line with the European Heart Survey (52%). The numbers of PCIs and CABGs (27 and 38%) in PREVEND were higher than the rates in European and American Surveys (25 to 33% and 5 to 12%, respectively), probably due to a longer follow-up time.15-17 The number of revascularisations was comparable with the ICTUS trial. In ICTUS, high-risk ACS subjects were randomised to an early invasive or conservative strategy under modern antiplatelet therapy. 18 Early CAG was followed by a revascularisation procedure in 79 vs. 54% of the ‘conservative’ patients. These data confirm the need for a revascularisation procedure in many subjects with ACS in the days or weeks following the acute presentation.

Coronary angiographic findings and subsequent revascularisation procedures

Coronary angiographies in subjects with STEMI or ACS were mostly followed by a revascularisation procedure. This was not the case for CAGs in subjects with stable angina, which was defined as angina or anginalike symptoms and the indication for most first CAGs. The high number (61%) of these CAGs not followed by a revascularisation procedure is in line with a large European registry.1 This high number is worrisome, since CAG is associated with considerable costs, and a small, but significant risk of major complications. There are two potential explanations for this phenomenon.

First, it has been reported that some subjects with an indication for a revascularisation procedure receive conservative treatment. This issue has been evaluated by several studies,2,8,9,19 in one of which the UMCG Thoraxcentre also participated.8,9 The relevance of this issue has been highlighted by the observation that in appropriate candidates for a revascularisation procedure, an underuse of revascularisation procedures was associated with a worse clinical outcome.2,20 In PREVEND, a decision to perform a revascularisation procedure was taken by the UMCG Thoraxcentre multidisciplinary team for 90% of subjects with obstructive CAD. In the other subjects performance of a revascularisation procedure was discussed, but conservative treatment was continued, due to presence of contraindications for a revascularisation procedure.

Second, current clinical guidelines advise carrying out noninvasive tests for the detection of myocardial ischaemia prior to CAG.4,21 Although we have not included the results of noninvasive tests in the current analysis, the high number of CAGs for stable angina in the absence of any coronary lesion, which is in line with previous reports,22 raises the suspicion that currently available noninvasive tests have a limited ability to differentiate between subjects at high vs. low coronary risk. Perhaps new imaging modalities that provide anatomical information on CAD, such as electron beam computed tomography or multislice detector computed tomography, will improve risk stratification prior to CAG. Future studies are needed to evaluate the impact of such a strategy on the incidence on CAG.

Impact of microalbuminuria on CAD

Microalbuminuria has been found to be present in 3 to 15% of the general population23-25 and has been associated with increased coronary risk. 23,24,26,27 The pathophysiological link between microalbuminuria and increased coronary risk still needs to be elucidated. Microalbuminuria may imply a vulnerability for atherosclerosis due to its association with inflammatory and prothrombotic changes involved in endothelial dysfunction. 28-35 There is conflicting evidence that microalbuminuria reflects a systemic transvascular leakage of albumin, which may be associated with leakage of lipoproteins and other macromolecules.36-38 Finally, microalbuminuria has been regarded as a marker of generalised atherosclerosis, although this hypothesis has previously been denied.39 In our study, an association between microalbuminuria and MACE was demonstrated, which confirms earlier evidence on the impact of microalbuminuria on cardiovascular risk. Furthermore, in line with an earlier angiographic study,40 microalbuminuria was most frequently present in subjects who had severe CAD at CAG during follow-up. Whether microalbuminuria can be regarded as an appropriate screening tool in asymptomatic populations is subject to future investigation.

Limitation

The generalisability of our results may be somewhat limited since a part of our study population was selected for the presence of microalbuminuria. Our cohort may therefore represent a population with an increased cardiovascular risk profile when compared with a general population-based cohort. We realise that the subjects of the PREVEND study were selected for a different reason than the observation of incidence and therapeutic consequences of coronary angiographies. Therefore, for example, the number of diabetes subjects is not representative for a population undergoing CAG. Furthermore, our study was a single-centre study and limited by a low number of coronary events. However, the advantage of a cohort study lies in its prospective design, and its population-based approach may better reflect routine clinical practice than multinational registries on the incidence of invasive procedures. Furthermore, the uniqueness of our study lies in the fact that we only included subjects without prior documented CAD.

Conclusion

This large cohort study shows that two-thirds of diagnostic CAGs for stable angina were not followed by a revascularisation, in contrast to CAGs for STEMI or ACS. Furthermore, this study confirms the association between microalbuminuria and CAD.

Acknowledgement

This study was financially supported by grant E.013 of the Dutch Kidney Foundation (Nier Stichting Nederland). Dade Behring (Marburg, Germany) is acknowledged for supplying reagents and equipment for the determination of hs-CRP and urinary albumin.

References

- 1.Togni M, Balmer F, Pfiffner D, Maier W, Zeiher AM, Meier B. Percutaneous coronary interventions in Europe 1992-2001. Eur Heart J 2004;25:1208-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hemingway H, Crook AM, Feder G, Banerjee S, Dawson JR, Magee P, et al. Underuse of coronary revascularization procedures in patients considered appropriate candidates for revascularization. N Engl J Med 2001;344:645-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatt DL, Roe MT, Peterson ED, Li Y, Chen AY, Harrington RA, et al. Utilization of early invasive management strategies for high-risk patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: results from the CRUSADE Quality Improvement Initiative.JAMA 2004;292:2096-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scanlon PJ, Faxon DP, Audet AM, Carabello B, Dehmer GJ, Eagle KA, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for coronary angiography. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines (Committee on Coronary Angiography). Developed in collaboration with the Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33:1756-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smilde TD, Asselbergs FW, Hillege HL, Voors AA, Kors JA, Gansevoort RT, et al. Mild renal dysfunction is associated with electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Hypertens 2005;18:342-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van de Werf F, Ardissino D, Betriu A, Cokkinos DV, Falk E, Fox KA, et al. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. The Task Force on the Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2003;24:28-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertrand ME, Simoons ML, Fox KA, Wallentin LC, Hamm CW, McFadden E, et al. Management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2002;23:1809-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rigter H, Meijler AP, McDonnell J, Scholma JK, Bernstein SJ. Indications for coronary revascularisation: a Dutch perspective. Heart 1997;77:211-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meijler AP, Rigter H, Bernstein SJ, Scholma JK, McDonnell J, Breeman A, et al. The appropriateness of intention to treat decisions for invasive therapy in coronary artery disease in the Netherlands. Heart 1997;77:219-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith SC Jr, Dove JT, Jacobs AK, Kennedy JW, Kereiakes D, Kern MJ, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines of percutaneous coronary interventions (revision of the 1993 PTCA guidelines) – executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (committee to revise the 1993 guidelines for percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty). J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:2215-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001;285:2486-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 1997;20:1183-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, Anderson JL, Cannon RO, III, Criqui M, et al. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation 2003;107:499-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silber S, Albertsson P, Aviles FF, Camici PG, Colombo A, Hamm C, et al. Guidelines for percutaneous coronary interventions: the task force for percutaneous coronary interventions of the European society of cardiology. Eur Heart J 2005;26:804-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhatt DL, Roe MT, Peterson ED, Li Y, Chen AY, Harrington RA, et al. Utilization of early invasive management strategies for high-risk patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: results from the CRUSADE Quality Improvement Initiative. JAMA 2004;292:2096-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox KA, Goodman SG, Anderson FA, Jr., Granger CB, Moscucci M, Flather MD, et al. From guidelines to clinical practice: the impact of hospital and geographical characteristics on temporal trends in the management of acute coronary syndromes. The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Eur Heart J 2003; 24:1414-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasdai D, Behar S, Wallentin L, Danchin N, Gitt AK, Boersma E, et al. A prospective survey of the characteristics, treatments and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes in Europe and the Mediterranean basin; the Euro Heart Survey of Acute Coronary Syndromes (Euro Heart Survey ACS). Eur Heart J 2002;23:1190-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Winter RJ, Windhausen F, Cornel JH, Dunselman PH, Janus CL, Bendermacher PE, et al. Early invasive versus selectively invasive management for acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1095-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shekelle PG, Kahan JP, Bernstein SJ, Leape LL, Kamberg CJ, Park RE. The reproducibility of a method to identify the overuse and underuse of medical procedures. N Engl J Med 1998;338:1888-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Filardo G, Maggioni AP, Mura G, Valagussa F, Valagussa L, Schweiger C, et al. The consequences of under-use of coronary revascularization; results of a cohort study in Northern Italy. Eur Heart J 2001;22:654-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibbons RJ, Abrams J, Chatterjee K, Daley J, Deedwania PC, Douglas JS, et al. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for the management of patients with chronic stable angina – summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina). Circulation 2003;107:149-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phibbs B, Fleming T, Ewy GA, Butman S, Ambrose J, Gorlin R, et al. Frequency of normal coronary arteriograms in three academic medical centers and one community hospital. Am J Cardiol 1988; 62:472-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hillege HL, Fidler V, Diercks GF, Van Gilst WH, De Zeeuw D, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Urinary albumin excretion predicts cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality in general population. Circulation 2002;106:1777-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borch-Johnsen K, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Strandgaard S, Schroll M, Jensen JS. Urinary albumin excretion. An independent predictor of ischemic heart disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1999;19:1992-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dinneen SF, Gerstein HC. The association of microalbuminuria and mortality in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. A systematic overview of the literature. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:1413-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hillege HL, Janssen WM, Bak AA, Diercks GF, Grobbee DE, Crijns HJ, et al. Microalbuminuria is common, also in a nondiabetic, nonhypertensive population, and an independent indicator of cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular morbidity. J Intern Med 2001;249:519-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yudkin JS, Forrest RD, Jackson CA. Microalbuminuria as predictor of vascular disease in non-diabetic subjects. Islington Diabetes Survey. Lancet 1988;2:530-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deckert T, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Borch-Johnsen K, Jensen T, Kofoed-Enevoldsen A. Albuminuria reflects widespread vascular damage. The Steno hypothesis. Diabetologia 1989;32:219-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barzilay JI, Peterson D, Cushman M, Heckbert SR, Cao JJ, Blaum C, et al. The relationship of cardiovascular risk factors to microalbuminuria in older adults with or without diabetes mellitus or hypertension: the cardiovascular health study. Am J Kidney Dis 2004;44:25-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stehouwer CD, Gall MA, Twisk JW, Knudsen E, Emeis JJ, Parving HH. Increased urinary albumin excretion, endothelial dysfunction, and chronic low-grade inflammation in type 2 diabetes: progressive, interrelated, and independently associated with risk of death. Diabetes 2002;51:1157-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stehouwer CD, Nauta JJ, Zeldenrust GC, Hackeng WH, Donker AJ, den Ottolander GJ. Urinary albumin excretion, cardiovascular disease, and endothelial dysfunction in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Lancet 1992;340:319-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Festa A, D’Agostino R, Howard G, Mykkanen L, Tracy RP, Haffner SM. Inflammation and microalbuminuria in nondiabetic and type 2 diabetic subjects: The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Kidney Int 2000;58:1703-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clausen P, Jensen JS, Jensen G, Borch-Johnsen K, Feldt-Rasmussen B. Elevated urinary albumin excretion is associated with impaired arterial dilatory capacity in clinically healthy subjects. Circulation 2001;103:1869-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clausen P, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Jensen G, Jensen JS. Endothelial haemostatic factors are associated with progression of urinary albumin excretion in clinically healthy subjects: a 4-year prospective study. Clin Sci (Lond) 1999;97:37-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McFarlane SI, Banerji M, Sowers JR. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:713-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Furtner M, Kiechl S, Mair A, Seppi K, Weger S, Oberhollenzer F, et al. Urinary albumin excretion is independently associated with carotid and femoral artery atherosclerosis in the general population. Eur Heart J 2005;26:279-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jensen JS. Renal and systemic transvascular albumin leakage in severe atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1995;15:1324-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jensen JS, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Borch-Johnsen K, Jensen KS, Nordestgaard BG. Increased transvascular lipoprotein transport in diabetes: association with albuminuria and systolic hypertension. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:4441-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jager A, Kostense PJ, Ruhe HG, Heine RJ, Nijpels G, Dekker JM, et al. Microalbuminuria and peripheral arterial disease are independent predictors of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, especially among hypertensive subjects: five-year follow-up of the Hoorn Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1999;19:617-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tuttle KR, Puhlman ME, Cooney SK, Short R. Urinary albumin and insulin as predictors of coronary artery disease: An angiographic study. Am J Kidney Dis 1999;34:918-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]