Abstract

Brugada syndrome is an inherited cardiac disease and is associated with a peculiar pattern on the electrocardiogram and an increased risk of sudden death. Electrical storm is a malignant but rare phenomenon in symptomatic patients with Brugada syndrome. We describe a patient who presented with repetitive ICD discharges during two episodes of recurrent VF. After the initiation of isoproterenol infusion and oral quinidine, the ventricular tachyarrhythmias were successfully suppressed. (Neth Heart J 2007;15:151-4.)

Keywords: Brugada syndrome, isoproterenol, quinidine, ventricular fibrillation (recurrent)

Brugada syndrome is a cardiac disease which demonstrates an autosomal dominant inheritance with variable expression and is associated with a pseudo right bundle branch block (RBBB), ST-segment elevation and terminal T-wave inversion in the precordial leads V1 to V3. Brugada syndrome accounts for approximately 20% of sudden arrhythmic deaths in patients without structural heart disease.1 The cellular basis or mechanism thought to underlie the STsegment elevation and the higher susceptibility for ventricular fibrillation in Brugada syndrome is an imbalance of transmembrane ionic currents in the right ventricular epicardium resulting in a transmural voltage gradient due to the loss of the phase 2 action potential dome,2 although there is evidence to support other hypotheses (e.g. conduction delay in the right ventricular outflow tract).3,4 In as many as one-third of all patients, sudden cardiac death is the first clinical manifestation of the disease. Patients who present with life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias or unexplained syncope have a higher risk for subsequent events compared with asymptomatic patients.5-7

The only established therapy for preventing sudden cardiac death (SCD) due to VF in this disease is insertion of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD). The effect is confined to the termination of VF and ICDs cannot influence the recurrence of VF. Although there is no proven pharmacological treatment for the prevention of SCD in Brugada syndrome, there are data suggesting that quinidine and hydroquinidine are successful in preventing spontaneous VF as well as inducible arrhythmias on electrophysiological (EP) testing.8The prevalence of ventricular arrhythmias can be quite high in Brugada syndrome; however, the occurrence of VF storm (more then 3 VF episodes over 24 hours) is very rare and seldom reported. Two drugs (isoproterenol and quinidine) have been reported to prevent the recurrence of ventricular fibrillation and repetitive traumatising therapeutic shocks in patients with an ICD during electrical storm.9-11

Case study

A 45-year-old man presented to the emergency room of a community hospital with repetitive ICD shocks. ICD interrogation revealed an electrical storm with nine therapeutic ICD discharges for episodes of VF. The last four of these appropriate ICD discharges occurred in a time span of less than one hour. Before referral to our hospital he had been treated with oxazepam infusion (a benzodiazepine) and an oral dose of 200 mg of a ‘slow-release’ β-blocking agent (metoprolol).

Two years ago this patient presented with syncope in the absence of obvious structural heart disease and an ECG compatible with Brugada syndrome with a type 2 pattern (figure 1) for which an ICD was implanted. One year later he received an upgrading to a high-energy device because two successive shocks of 31 joules were needed to convert VF into sinus rhythm.

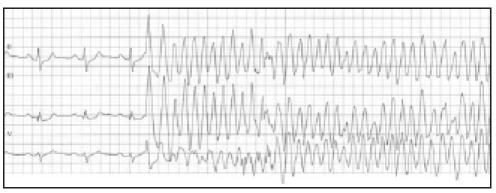

Figure 1.

ECG with typical features of Brugada syndrome (type 2 pattern).

Approximately 24 hours after admission to our medium care unit the patient developed a second electrical storm; five episodes of VF induced by monomorphic ventricular premature complexes and terminated by ICD discharges (figures 2 and 3). He was sent to the CCU where an isoproterenol infusion was started at 1 μg/min. After starting the isoproterenol, there were no new episodes of VF, the AV time shortened slightly and the ST-segment elevation previously seen decreased in the precordial lead V2 (figures 4A en 4B). Quinidine was initiated as oral therapy at a starting dose of 200 mg three times a day, which was increased to 400 mg three times a day. One day after starting quinidine the isoproterenol infusion was discontinued. In the next few days ventricular fibrillation did not recur and there was an ongoing resolution of the STsegment elevation in the precordial leads (figure 4C).

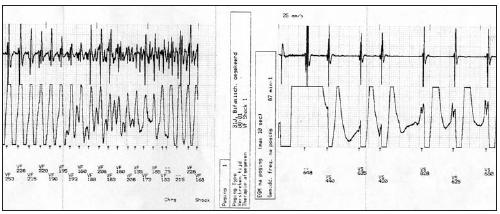

Figure 2.

The onset of ventricular fibrillation, induced by a (short coupled) ventricular premature complex. See text for details.

Figure 3.

Ventricular fibrillation converted to sinus rhythm by ICD discharge. See text for details.

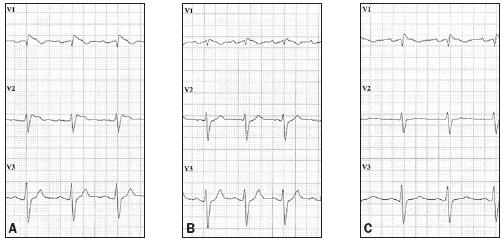

Figure 4.

The ECG A) on admission to the CCU; B) after initiation of the isoproterenol infusion and before oral quinidine was started. There is a decrease in ST-segment elevation especially in lead V2; C) after quinidine 200 mg three times a day and after discontinuing the isoproterenol infusion, with ongoing resolution of the ST-segment elevation. See text for details.

Discussion

Brugada syndrome is considered a primary electrical disease in which an outward shift in the balance of transmembrane ionic currents at the end of phase 1 and phase 2 of the action potential could be responsible for the ionic and cellular basis for the ST-segment elevation. The outward current is mainly due to activation of the transient outward current (Ito), and the inward current is mainly due to activation of an inward calcium current (ICa) and an inward sodium current (INa). The net outward shift of this current balance leads to a loss of the dome or phase 2 of the action potential. Such changes may affect the right ventricular epicardium more markedly than the endocardium and produce a marked voltage gradient in the membrane potential between the endocardial and epicardial sides of the right ventricular muscle fibres during phase 2 (a change corresponding to the characteristic ST-segment elevation in V1 to V3 in the ECGs of Brugada syndrome).12

The loss of the action potential dome in the epicardium but not in the endocardium results in the development of a marked transmural dispersion of repolarisation and refractoriness, responsible for the development of a vulnerable window during which a premature impulse or extrasystole can induce a reentrant arrhythmia. Because the loss of the action potential dome in the epicardium is usually heterogeneous, it leads to the development of epicardial dispersion of repolarisation and refractoriness. Conduction of the action potential dome from sites at which it is maintained to sites at which it is lost causes local pre-excitation via a phase 2 re-entry mechanism, leading to the development of a very closely coupled extrasystole, which captures the vulnerable window across the wall, thus triggering a circus movement reentry in the form of VT or VF.12,13

Isoproterenol in Brugada syndrome

In the last three years our patient has presented three times with episodes of VF. All three events occurred during the summer holidays, when the balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system should be in favour of the latter. This could represent the established role of the autonomic nervous system (especially an enhanced vagal tone) in the development of VF in patients with Brugada syndrome. 12,14 Theoretically there could be a therapeutic effect of sympathomimetic agents in the treatment of electrical storms, which is supported by experimental studies and case reports. These studies show that sympathetic agonists can normalise the ST-segment elevation and prevent VF in Brugada syndrome. Intravenous isoproterenol administration is especially known to be effective in suppressing ST elevation in leads V1 to V3, and in restoring the action potential dome in experimental models of this syndrome and in patients with Brugada syndrome, because it increases the ICa secondary to an elevation in the intracellular level of cyclic AMP.9,12,14,15

In our patient, despite no increase in heart rate after starting isoproterenol infusion, there was a clear positive result on the recurrence of VF. This shows that the therapeutic effect of β-adrenergic stimulation is probably due to the direct effect on the myocytes, instead of the elevation of the heart rate.

Sympathetic stimulation results in a marked increase in ICa, which can compensate for the prominent Ito (outward current of K) and the loss of plateau during phase 2 of the action potential, resulting in a decrease in electrical heterogeneity that is thought to underlie the ST elevation typical of Brugada.12 This decrease in transmural voltage gradient leads to a normalisation of the ST segment and prevents induction of VF by short-coupled premature complexes (during phase 2 of the action potential).

Efficacy of quinidine treatment

Brugada et al. stated that they have disappointing results in the treatment of electrical storms using quinidine.16 However, other reports show a positive result of oral quinidine in the treatment of VF storm in patients with Brugada syndrome.10,11 In these reports the dosage of oral quinidine was comparable with the dose in our report. A variety of pathophysiological conditions and pharmacological interventions, which either increase the transmembrane outward currents or reduce the inward currents, should produce a loss of the action potential dome in the right ventricular epicardium and facilitate the occurrence of VF. Phase 2 of the action potential could be abolished by reducing the INa as predicted by the ST-segment elevation after the application of Class IC agents and restored by increasing the inward current, e.g., by enhancing the ICa (e.g. by the application of isoproterenol) or by decreasing the outward Ito current, (e.g., by the application of quinidine), with a normalisation of the ST-segment elevations first reported by Alings et al.17 The anticholinergic action on the heart might contribute to the anti-VF effect of the drug by increasing the heart rate.

In a report by Belhassen et al., patients with Brugada syndrome, both symptomatic and asymptomatic, were treated with quinidine to evaluate the ability of preventing VF inducibility during EP testing. Patients who had inducible VF at baseline EP study were treated with quinidine and EP testing was repeated. In 22 of 25 (88%) patients, VF was no longer inducible after quinidine.8

There are, however, some limitations in using quinidine for the prevention of VF in patients with Brugada syndrome. There are some risks with antiarrhythmic agents with regard to the potential for a loss of efficacy or proarrhythmic effects under a number of conditions including hypokalaemia, hypomagnesaemia, bradycardia, therapy with other agents that alter repolarisation, metabolic inhibitors, and changes in myocardial substrates. Furthermore, quinidine is known to have other noncardiac side effects including abdominal cramping, diarrhoea, cinchonism, which consists of decreased hearing, tinnitus, and blurred vision, thrombocytopenia, lupus syndrome, and anticholinergic side effects including a dry mouth, urinary retention and so on. These side effects may affect the compliance with the drug.

Conclusion

Brugada syndrome is a unique form of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation (VF), and is characterised by an ECG pattern with right bundle branch block (J wave), ST-segment elevation and terminal T-wave inversion in leads V1 to V3. It accounts for approximately 20% of all cases of sudden cardiac death in patients with structurally normal hearts and appears to be more frequent in Southeast Asia than in other regions. To date, the only established therapy for preventing sudden cardiac death due to VF in this disease is to insert an ICD. Although there is no room for discussion regarding the excellent and uniform efficacy of ICDs for terminating VF, the effect is confined to the termination of VF, and ICDs cannot contribute to the prevention of VF. Therefore, there are some concerns regarding ICD therapy. The first is electrical storm associated with VF or polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, which is defined as frequent appropriate ICD shock deliveries for ventricular tachyarrhythmias of ≥3 times over 24 hours.

In patients with aborted sudden cardiac death or syncope of unknown origin (symptomatic Brugada syndrome), no one argues that the implantation of an ICD is the first-line therapy regardless of the findings of the EP study. For those patients, drug therapy plays a complimentary role to the ICD by reducing the number of ICD shocks delivered. Prevention of VF contributes to the improvement in the quality of life of the patients by avoiding uncomfortable ICD shock deliveries.

References

- 1.Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992;20:1391-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antzelevitch C. The Brugada syndrome: ionic basis and arrhythmia mechanisms. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2001;12:268-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meregalli P, Wilde A, Tan H. Pathophysiological mechanisms of Brugada syndrome: Depolarization disorder, repolarization disorder, or more? Cardiovasc Res 2005;67:367-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coronel R, Casini S, Koopmann TT, Wilms-Schopman FJG, Verkerk AO, de Groot JR, et al. Right ventricular fibrosis and conduction delay in a patient with clinical signs of Brugada syndrome: a combined electrophysiological, genetic, histopathologic, and computational study. Circulation 2005;112:2769-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brugada J, Brugada R, Antzelevitch C, Towbin J, Nademanee K, Brugada P. Long-term follow-up of individuals with the electrocardiographic pattern of right bundle-branch block and ST-segment elevation in precordial leads V1 to V3. Circulation 2002;105:173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eckardt L, Probst V, Smits JPP, Schulze Bahr E, Wolpert C, Schimpf R, et al. Long-term prognosis of individuals with right precordial ST-segment-elevation Brugada syndrome. Circulation 2005;111:257-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brugada J, Brugada R, Brugada P. Natural history of Brugada syndrome: the prognostic value of programmed electrical stimulation of the heart. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2003;14:455-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belhassen B, Glick A, Viskin S. Efficacy of quinidine in high-risk patients with Brugada syndrome. Circulation 2004;110:1731-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maury P, Couderc P, Delay M, Boveda S, Brugada J. Electrical storm in Brugada syndrome successfully treated using isoprenaline. Europace 2004;6:130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mok NS, Chan NY, Chiu AC. Successful use of quinidine in treatment of electrical storm in Brugada syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2004;27:821-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bettiol K, Gianfranchi L, Scarfo S, Pacchioni F, Pedaci M, Alboni P. Successful treatment of electrical storm with oral quinidine in Brugada syndrome. Ital Heart J 2005;6:601-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan GC, Antzelevitch C. Cellular basis for the Brugada syndrome and other mechanisms of arrhythmogenesis associated with STsegment elevation. Circulation 1999;100:1660-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lukas A, Antzelevitch C. Phase 2 reentry as a mechanism of initiation of circus movement reentry in canine epicardium exposed to simulated ischemia. Cardiovasc Res 1996;32:593-603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasanuki H, Ohnishi S, Ohtura M, Matsuda N, Nirei T, Isogai R, et al. Idiopathic ventricular fibrillation induced with vagal activity in patients without obvious heart disease. Circulation 1997;95:2277-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watanabe A, Fukushima Kusano F, Morita H, Miura D, Sumida W, Hiramatsu S, et al. Low-dose isoproterenol for repetitive ventricular arrhythmia in patients with Brugada syndrome. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1579-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brugada P, Brugada R, Antzelevitch C, Brugada J. The Brugada Syndrome. Mal Coeur Vaiss 2005;98:115-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alings M, Dekker L, Sadee A, Wilde A. Quinidine induced electrocardiographic normalization in two patients with Brugada syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2001;24:1420-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]