Abstract

In Escherichia coli, homologous recombination initiated at double-stranded DNA breaks requires the RecBCD enzyme, a multifunctional heterotrimeric complex that possesses processive helicase and exonuclease activities. Upon encountering the DNA regulatory sequence, χ, the enzymatic properties of RecBCD enzyme are altered. Its helicase activity is reduced, the 3′→5′nuclease activity is attenuated, the 5′→3′ nuclease activity is up-regulated, and it manifests an ability to load RecA protein onto single-stranded DNA. The net result of these changes is the production of a highly recombinogenic structure known as the presynaptic filament. Previously, we found that the recC1004 mutation alters χ-recognition so that this mutant enzyme recognizes an altered χ sequence, χ*, which comprises seven of the original nucleotides in χ, plus four novel nucleotides. Although some consequences of this mutant enzyme-mutant χ interaction could be detected in vivo and in vitro, stimulation of recombination in vivo could not. To resolve this seemingly contradictory observation, we examined the behavior of a RecA mutant, RecA730, that displays enhanced biochemical activity in vitro and possesses suppressor function in vivo. We show that the recombination deficiency of the RecBC1004D-χ* interaction can be overcome by the enhanced ability of RecA730 to assemble on single-stranded DNA in vitro and in vivo. These data are consistent with the previous findings showing that the loading of RecA protein by RecBCD is necessary in vivo, and they also show that RecA proteins with enhanced single-stranded DNA binding capacity can partially bypass the need for RecBCD-mediated loading.

Introduction

RecBCD enzyme is a helicase/nuclease that functions at the initiation step of recombinational DNA repair in Escherichia coli 1,2. From a nearly blunt double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) end, RecBCD enzyme unwinds and degrades the dsDNA, powered by the two motor subunits, RecB and RecD 3. When the enzyme encounters the recombination hotspot sequence, χ (5′-GCTGGTGG), from the 3′ side on one of the DNA strands4, its 5′ to 3′ nuclease activity is up-regulated and its 3′ to 5′ nuclease activity is down-regulated 5–7. The consequence of these changes is the production of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) with the χ sequence at the 3′-terminus; this product is referred to as the “χ-containing ssDNA”. In addition, RecBCD enzyme pauses at χ for approximately 5 seconds, and then resumes unwinding at a rate that is about 2-fold slower than the rate prior to χ recognition 8,9. Perhaps the most biologically important property of the χ-modified RecBCD enzyme is its ability to load RecA onto ssDNA 10,11. Although the molecular details of this regulatory process remain to be fully understood, the changes elicited by χ-recognition are not the result of RecD-ejection at χ because, even though the RecD subunit regulates RecBCD enzyme activities 12–14, recent single-molecule studies showed that the RecD subunit continues to translocate with the holoenzyme after χ recognition 9. Rather, single-molecule studies 8,9, the x-ray crystallographic structure of the enzyme-DNA complex 15, and analysis of a RecBCD enzyme homolog (the Bacillus subtilis AddAB enzyme) 16 suggest that binding of the χ sequence itself to RecBCD enzyme elicits the allosteric changes that underlie the enzymatic alterations.

Many studies suggest that the degradative capacity of RecBCD enzyme is part of an antiviral system of E. coli that works in conjunction with the restriction-modification system 17,18; the χ sequence allows RecBCD enzyme to recognize chromosomal DNA and to thereby protect it from degradation. Consequently, in recBC-deficient cells, DNA double-strand breaks accumulate 19–21. The χ sequence is over-represented in the E. coli genome 22, whereas it is absent from or under-represented in bacteriophages (N. H., unpublished observations). Therefore, the χ sequence is an identification marker of the E. coli genome. Interestingly, this relationship between a nuclease and its cognate attenuation sequence is conserved in many prokaryotes 23. In Salmonella typhimurium, the same eight-nucleotide sequence functions as χ 24, whereas in Lactococcus lactis, Bacillus subtilis and Haemophilus influenzae, the cognate χ sequences are 5′-GCGCGTG, 5′-AGCGG, and 5′-GNTGGTGG, respectively 25–27.

Mutant alleles of recBCD that recovered all the activities of RecBCD enzyme, except for χ recognition, were originally isolated as pseudo-revertants of a mutant with a recC null phenotype. This class of mutants, called RecC*, showed almost the same basal level of recombination as wild type, but this recombination was not stimulated by χ 28,29. Sequencing revealed that, due to a frameshift, all of the analyzed alleles possess substitutions of amino acid residues between positions 647 and 655 in the recC gene 30. It was found that a novel sequence, different from the canonical χ sequence, was specifically recognized by one of these mutants, recC1004, in vivo 29. Resembling the original χ sequence in its genetic behavior 31, this novel sequence conferred an increased growth rate to red− gam− bacteriophage λ on the recC1004 strain. This novel sequence, which was named χ*, is the 11 nucleotide sequence, 5′-GCTGGTGCTCG 29 and comprises the first seven bases of the E. coli χ, plus 4 additional novel bases. As for the wild type pair, the nuclease activity of the recC1004 mutant protein was attenuated in vivo by the χ* sequence 29. Purified RecBC1004D enzyme possessed wild type levels of dsDNA exonuclease and helicase activities, but displayed reduced recognition of wild type χin vitro 30. However, this mutant RecBCD enzyme recognized the mutant χ sequence more efficiently than wild type χ, albeit with a lower efficiency than the wild-type enzyme recognized wild type χ. Furthermore, χ*-dependent joint molecule formation was stimulated by the RecBC1004D enzyme, demonstrating that RecA-loading activity was preserved but, again, the yield was lower than for the fully wild type reaction. Despite these biochemical results, stimulation of recombination in vivo using bacteriophage λ crosses could not be detected for this RecC1004 - χ* interaction 29. This inconsistency was explained by a greater detection sensitivity of the in vitro assays relative the in vivo assay 30.

E. coli possesses a second recombination pathway, called the RecF pathway 2. In the absence of RecBCD function, the RecF pathway can be activated to function at double-stranded DNA breaks by mutation of sbcB, which is in the gene encoding exonuclease I 32. RecF protein works together with RecO and RecR proteins to load RecA protein onto ssDNA complexed with ssDNA-binding protein (SSB) protein at 5′-end of dsDNA gaps 33. Mutations in the recF gene can be suppressed by alleles of recA that display enhanced functionality 34–36. These mutant RecA proteins (e.g., RecA803 and RecA730) nucleate onto ssDNA more rapidly than wild type RecA protein 37,38. Biochemical analysis further established that these enhanced RecA proteins displaced SSB protein from ssDNA faster and more completely than wild type protein, and the resulting filaments were kinetically more resistant to subsequent displacement by SSB protein.

The relationship between RecA-loading in vitro and recombination activity in vivo is relatively unstudied. Toward this end, we examined the effect of the recA730 allele on the recombination phenotype of cells defective in recBCD function. We found that, in response to χ* recognition, RecBC1004D enzyme loaded RecA730 protein onto ssDNA to form nucleoprotein filaments that were more stable than those formed by wild type RecA protein. Furthermore, we found that recA730 suppressed the recombination deficiency of the mutant RecBC1004D-χ* interaction in vivo, showing that an intrinsic increased propensity to nucleate on ssDNA and to form more stable nucleoprotein filaments can compensate for the lower yield of χ*- containing ssDNA produced by RecBC1004D enzyme processing.

Results

RecA protein is loaded onto χ*-containing ssDNA by RecBC1004D enzyme

Previously, it was shown that the recC1004 mutation changed the specificity of χ recognition from the canonical sequence to a novel sequence, χ* 29. The purified RecBC1004D enzyme produced χ*-dependent joint molecules in response to χ* recognition, but with a lower yield than the wild type reaction 30. However, the interaction between RecBC1004D enzyme and χ* did not result in an increased frequency of recombination as measured by bacteriophage λ crosses 29, suggesting that the in vitro assay was more sensitive than the in vivo assay. To analyze the mutant interaction in more detail, RecA-loading assays were performed as described previously 10, but with one significant difference: ATPγS was not added to stabilize the RecA nucleoprotein filaments. By omitting the ATPγS, the resulting ATP-RecA nucleoprotein filaments were kinetically less stable, permitting experimental distinction between wild type and RecA730 proteins (see below).

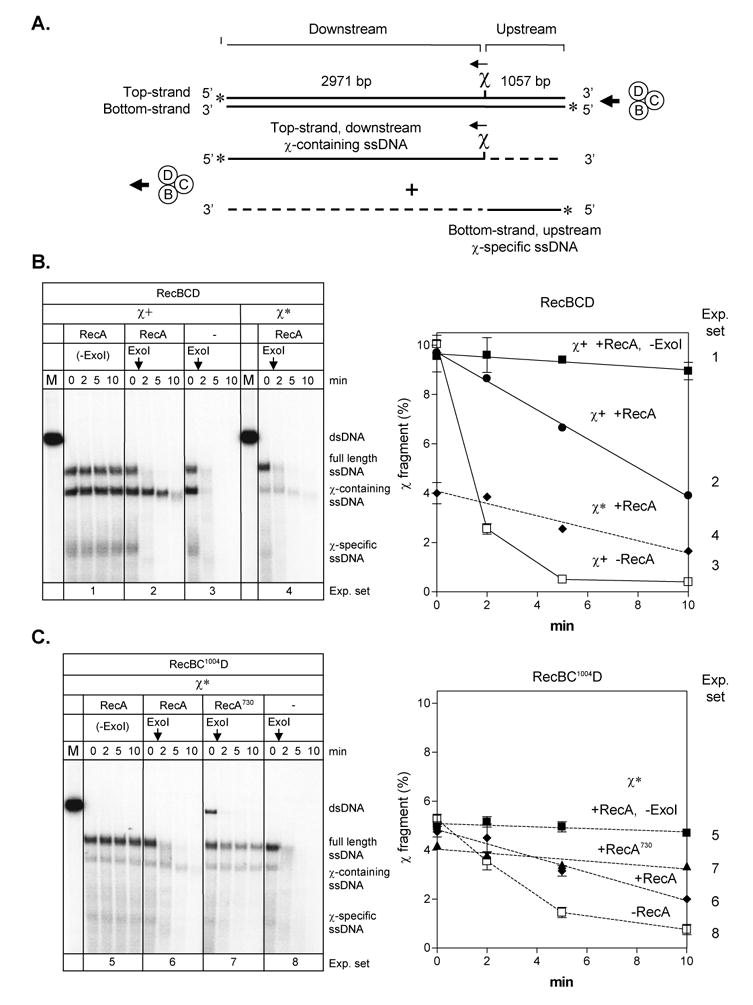

As shown in Figure 1, in response to χ-recognition, wild type RecBCD enzyme produced full-length ssDNA and two χ–specific ssDNA fragments (Figure 1B, experiment set 1). To determine whether RecA protein is bound to the 3′-end of any of these ssDNA products, exonuclease I, a 3′-specific ssDNA exonuclease, was added prior to deproteinization 10. As reported previously, when exonuclease I was added to the processing products that were formed in the absence of RecA protein, both the full length ssDNA and the χ-specific ssDNA were degraded within a few minutes because exonuclease I rapidly degrades ssDNA that is complexed with SSB protein (Figures 1B, experiment set 3, and 1C, experiment set 8). On the other hand, when RecA protein was present, the χ-containing ssDNA, but not the full length ssDNA nor the other χ-specific ssDNA, was protected by the RecA protein from exonuclease digestion (Figure 1B, experiment set 2) because exonuclease I digests the RecA-coated ssDNA slowly than the SSB-ssDNA complex 10,39. When RecBC1004D enzyme and a χ*-containing dsDNA were examined in the same reactions (Figure 1C), protection of the χ*-containing ssDNA by RecA protein was also detected (compare Figure 1C, experiment sets 5 and 6), even though production of the χ*-containing ssDNA was reduced by approximately half relative to production of the χ-specific ssDNA as was reported previously 30,40.

Figure 1. RecBCD and RecBC1004D enzymes load RecA and RecA730 proteins onto χ*–containing ssDNA.

A. Illustration of the substrate used and the major products produced by the helicase/nuclease activities of RecBCD enzyme upon χ recognition. B. Wild type RecBCD enzyme. Left: Gel showing RecA-loading onto χ-containing ssDNA, assayed by protection from exonuclease I digestion (present in all lanes except “-ExoI” controls). The proteins and linear dsDNA (χ+ or χ*) present are indicated at the top of the gel. The vertical arrows indicate the time of exonuclease I addition. Right: Quantification of χ–containing ssDNA protection. The amount of χ–containing ssDNA remaining is expressed relative to the initial amount of dsDNA (lane M): filled squares: RecA in the absence of exonuclease I (exp. set 1); filled circles: RecA (exp. set 2); open squares: RecA omitted (exp. set 3); and filled diamonds: RecA and χ* instead of χ (exp. set 4). C. RecBC1004D enzyme and χ*. Left: Gel showing RecA-loading onto χ*containing ssDNA, assayed by protection from exonuclease I digestion. The proteins (wild type RecA or RecA730) and linear dsDNA (χ*) present are indicated at the top of the gel. Right: Quantification of χ*–containing ssDNA protection: filled squares: RecA in the absence of exonuclease (exp. set 5); filled diamonds: RecA (exp. set 6); filled triangles: RecA730 (exp. set 7); and open squares: RecA omitted (exp. set 8). .

RecA730 protein is loaded onto χ-containing fragments more rapidly and produces more stable nucleoprotein filaments than wild type protein

The yield of χ*-containing ssDNA produced by the RecBC1004D enzyme is reduced relative to the wild type interaction, resulting in a lower yield of RecA nucleoprotein filaments needed for recombination 30. However, we reasoned that perhaps a mutant RecA protein which had an intrinsically greater SSB-displacement activity might increase the observed yield of active nucleoprotein filaments; consequently, recombination might be increased in vivo. Therefore, RecA730 protein was examined. The RecA730-ssDNA complex was found to produce nucleoprotein filaments that were more resistant to exonuclease I (Figure 1C, experiment set 7). Full length ssDNA was also protected by the mutant RecA protein, as expected from the enhanced SSB-displacement ability of RecA730 protein 38. RecA730 protein also protected ssDNA produced by RecQ, RecB1080CD, or RecB2109CD helicases from degradation (data not shown), showing that the increased protection is not specific to any DNA helicase, but rather it is consistent with its enhanced filament nucleation capability.

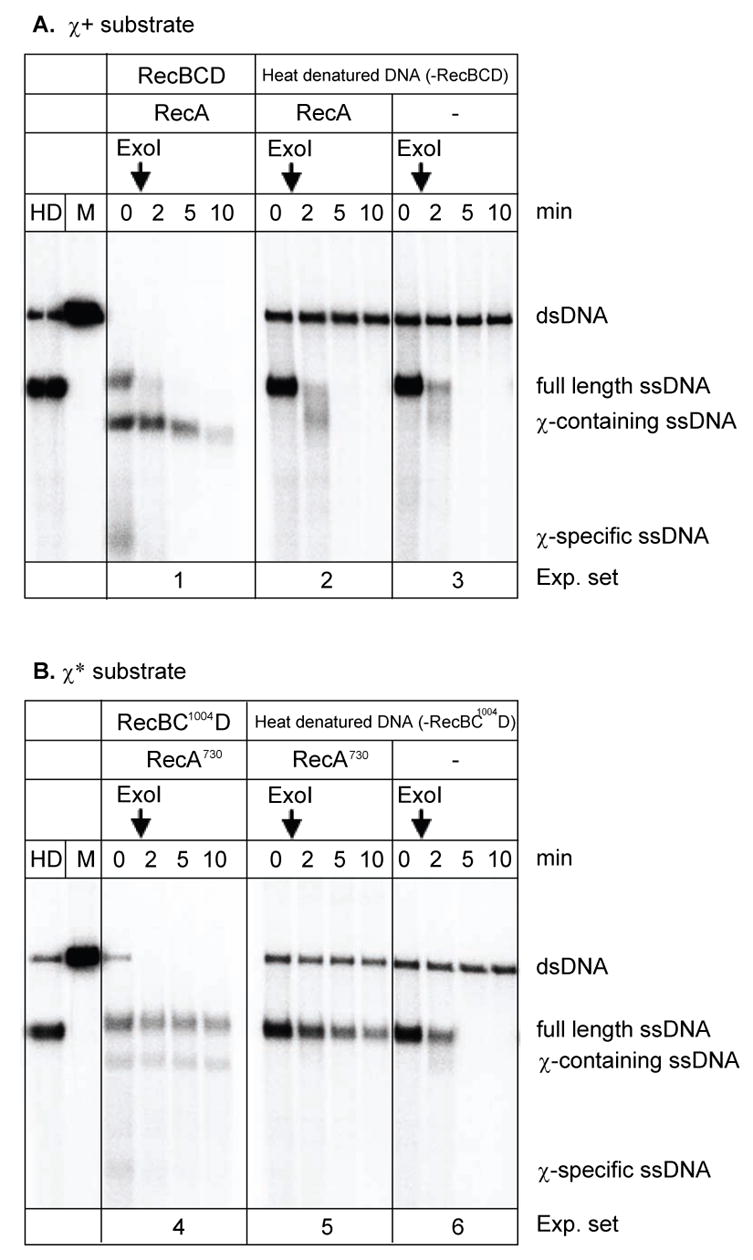

Enhanced assembly of nucleoprotein filaments is an intrinsic property of RecA730

To confirm that the increased protection of all ssDNA is intrinsic to RecA730 protein, reactions where RecA nucleoprotein filament assembly was coupled to ssDNA production by RecBCD enzyme were compared to reactions where RecA protein was assembled on heat-denatured DNA in the absence of RecBCD enzyme 10,39. As previously reported, wild type RecA protein did not protect ssDNA produce by heat-denaturation from exonuclease I degradation, because it cannot displace SSB protein efficiently (Figure 2A, experiment set 2). In contrast, there was greater protection by RecA730 than by wild type protein of the full length ssDNA produced either by heat denaturation (Figure 2B, experiment set 5) or by RecBCD enzyme (Figure 2B, experiment set 4). This observation supports our conclusion that the higher nucleation frequency of RecA730 protein, which results in increased displacement of SSB protein, is responsible for the enhanced protection of any ssDNA produced.

Figure 2. RecA730 possesses an enhanced capacity to form stable nucleoprotein filaments on SSB-ssDNA complexes.

RecA nucleoprotein filaments were formed on heat-denatured linear dsDNA in the presence of SSB protein for comparison to nucleoprotein filament formation in the coupled RecA and RecBCD reactions. A. Wild type RecA protein and χ+ DNA. B. RecA730 protein and χ* DNA. The RecA proteins used in each experiment are indicated. The vertical arrows indicate the time of exonuclease I addition. Lanes marked “HD” and “M” represent heat-denatured and linear dsDNA, respectively. For comparison, experiments 1 and 4 are coupled reactions.

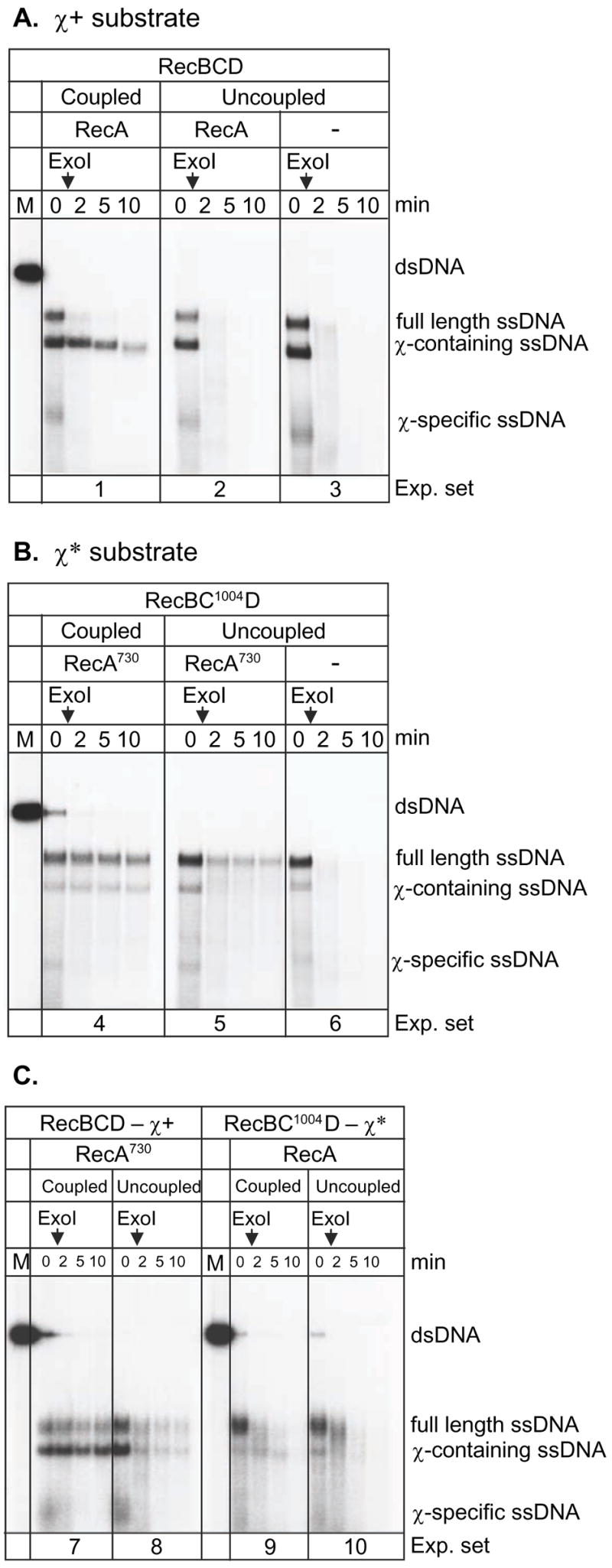

Previously, it was also shown that RecA protein was loaded onto χ-containing SSB-complexed ssDNA by RecBCD enzyme only when the RecA protein was present during DNA unwinding (a coupled reaction); in contrast, RecA protein was not loaded onto the χ-containing ssDNA when it was added subsequent to DNA processing by RecBCD enzyme (an uncoupled reaction) 10,39. In agreement, in an uncoupled reaction with wild type RecA protein, all of the ssDNA was digested by exonuclease I whereas, in a coupled reaction, only the χ–containing ssDNA was protected (Figure 3A, compare experiment sets 1 and 2). In contrast, but consistent with Figures 1 and 2, RecA730 protein afforded better protection to all ssDNA in both the coupled and uncoupled reactions, with both mutant and wild type RecBCD enzyme and both mutant and wild type χ sequences (Figures 3B and 3C). The enhanced ability of RecA730 protein, relative to wild type, to displace SSB protein is apparent in the coupled reactions (Figure 3B, experiment set 4 and Figure 3C, experiment set 7): both χ-containing ssDNA and full length ssDNA were more protected (compare to Figure 3A, experimental set 1 and Figure 3C, experiment set 9, respectively). Because the yield of χ*-containing ssDNA is always lower than that of the wild-type χ-containing ssDNA, the protection afforded by RecA730 is more difficult to assess by visual inspection; however, quantification of 5 independent replicates of Figure 3B shows that 76±7% of the χ*-containing ssDNA remained after 10 minutes in the coupled reaction (experiment set 4), whereas only 38±2% (two independent replicates) remained in the uncoupled reaction (experiment set 5). As expected, due to the absence of loading by RecBCD enzyme, in the uncoupled reaction, protection of the full length ssDNA (34±2%) was the same as that of the χ*-containing ssDNA (38±2%). Thus, RecA 730 protein can assemble more quickly on any ssDNA by an enhanced intrinsic polymerization capacity; in addition, it can be loaded onto χcontaining ssDNA by both wild type and mutant RecBCD enzyme in response to wild-type and mutant χ sequences.

Figure 3. RecA730 protein can be loaded onto χ-containing ssDNA to form nucleoprotein filaments that are more stable than those formed by wild type RecA protein.

A. Wild type RecBCD enzyme, RecA protein and χ+ DNA. “Coupled” experiments referred to reactions where RecA protein was present at the beginning of the DNA processing reaction by RecBCD enzyme. In “uncoupled” experiment, RecA protein was added after DNA processing by RecBCD enzyme. The vertical arrows indicate the time of exonuclease I addition. B. RecA730 protein, RecBC1004D enzyme, and χ* DNA. C. Comparison of RecA730 with wild type RecBCD and χ versus wild type RecA with RecBC1004D and χ*; both coupled and uncoupled reactions are shown.

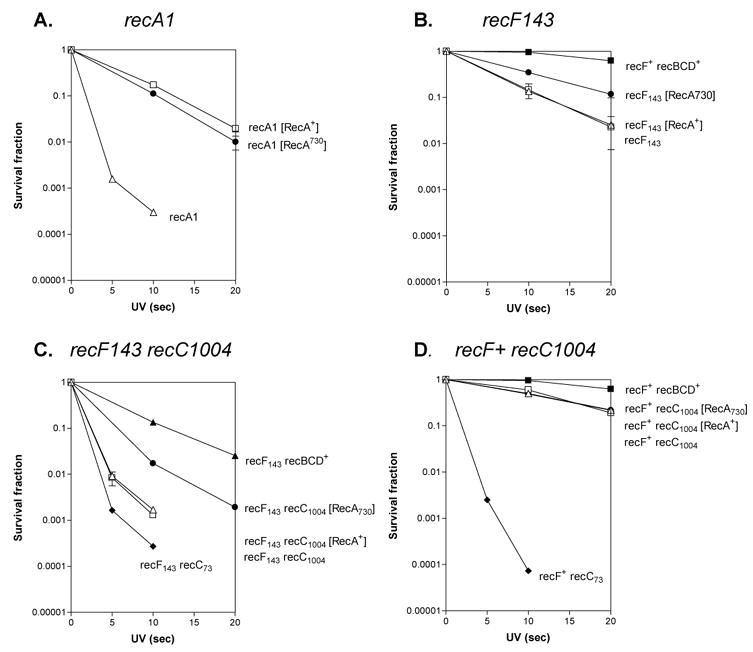

The RecA 730 mutation partially suppress the UV sensitivity of recF recC1004 strains

To determine whether the recombination deficiency of the RecBC1004D enzyme can be suppressed by RecA730 protein in vivo, the UV sensitivity of recC1004 mutants harboring RecA expression plasmids was measured. Expression of both recA730 and wild type recA suppressed the UV sensitivity of the recA− strain (Figure 4A). Also, as reported previously 34,36, recA730 partially suppressed a recF mutation (Figure 4B), whereas wild type recA could not. The recA730 mutation also partially suppressed the original recC1004 strain, which also carried a recF mutation and consequently showed severe UV sensitivity 28 (Figure 4C). To determine the effect of recA730 on the RecBCD pathway, a recF+ background was also investigated. In the recF+ background, however, the recC1004 mutation did not show a severe UV sensitivity (Figure 4D), and there was no detectable suppression of the modest UV sensitivity of the strain by recA730. Therefore, it is most likely that the partial suppression observed in recF− background by recA730 is due to suppression of the recF mutation, rather than the recC1004 mutation (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Suppression of UV sensitivity by recA730.

A. recA1 background. B. recF143 background. C. recF143 recC1004 background. D. recC1004 background. Open triangles represent the strains lacking any recA-expressing plasmid. Open squares represent the strains expressing wild type recA. Closed circles represent the strains expressing recA730; closed squares represent the wild type rec+ strains; closed diamonds represent the recC73 strains; and the closed triangles in panel C are recF143.

RecA730 restores the recombination deficiency of the RecC1004 - χ* interaction

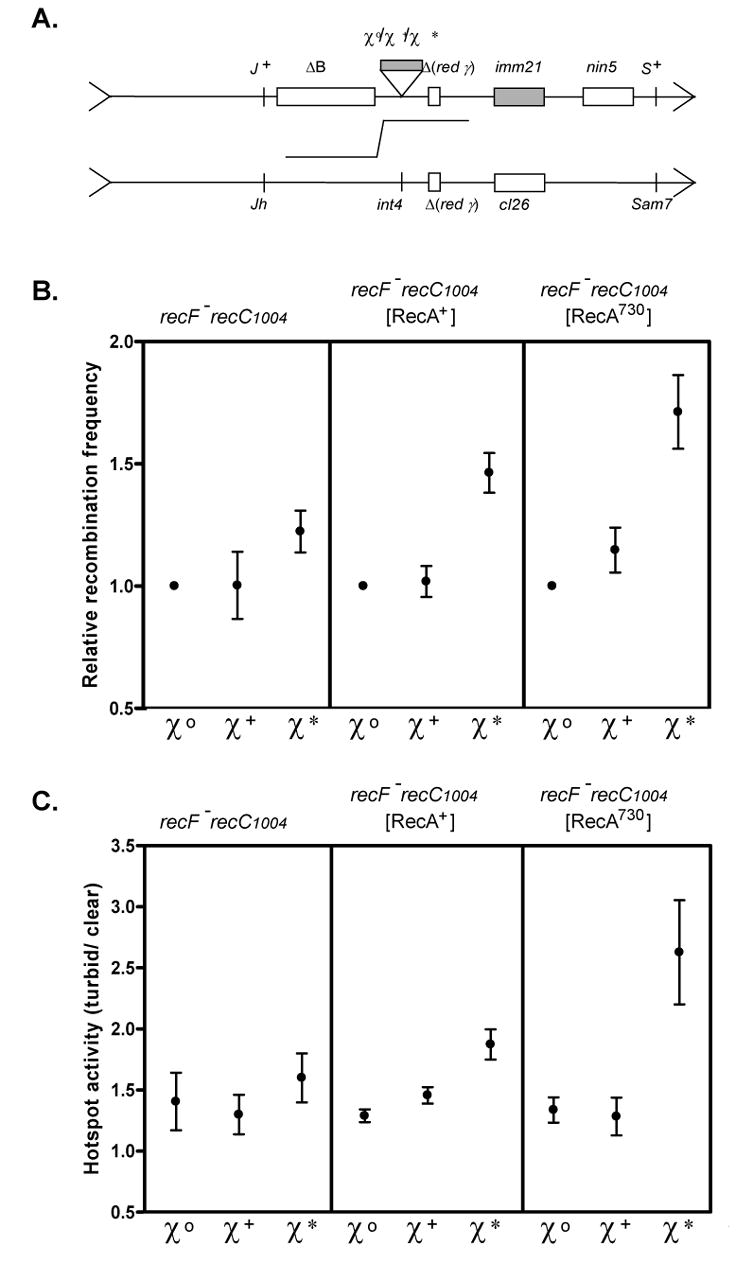

Partial suppression of the UV sensitivity of recF by recA730 was detected, but our in vitro findings suggested that RecA730 should also compensate for the lower production of χ*–containing ssDNA by RecBC1004D enzyme. To test this hypothesis, recombination between λ phages was investigated 29. The parental λ phages have either a Sam7 or Jh mutation, and the products of recombination crossover, recombinant phage possessing S+ and Jh, were selected (Figure 5A). In the recF recC1004 background, both the recombination frequency (Figure 5B left panel) and stimulation of recombination by χ+ and χ* was experimentally indistinguishable (Figure 5C left panel), as previously reported 29.

Figure 5. recA730 restores the recombination hotspot activity of χ* in a recF recC1004 strain.

A. Design of the λ recombination crosses 29. Parental phages are defective for their phage-encoded recombination functions (red− γ−− int−). The S+ Jh recombinant phages were scored as to whether the plaque was turbid (cI+; crossover before the immunity region) or clear (cI−; crossover beyond the region). B. Recombination frequency. The relative value, normalized to the wild type (χ0) strain, of the ratio [S+ Jh recombinants/total phage] is plotted. Left panel is the recF143 recC1004 strain without plasmid (N = 3). Center panel is the same strain with the wild type recA expressing plasmid (N = 3). Right panel is the same strain with the recA730 expressing plasmid (N = 4). The recombination frequency and standard deviation for χ0 was 0.43 ± 0.08, 0.41± 0.14, and 0.43 ± 0.11 for the parental strain, wild type recA, and recA730, respectively. C. Hotspot activity. The ratio of turbid plaques to clear plaques is plotted.

However, in the presence of RecA730, the frequency of recombination in recC1004 strains was increased (Figure 5B, right panel). Also, and more importantly, χ* shows significant recombination hotspot activity in the recC1004 background when RecA730 protein was present (Figure 5C, right panel). Even in the recF+ background, a similar suppression of RecBC1004D-χ* recombination was observed (data not shown). Using this identical assay, wild type RecBCD and χ+ showed a 4.2-fold increase in recombination frequency (the recombination frequency for χ0 λ phage was 0.50 ± 0.18), and a 6.5-fold increase for hotspot activity assay (data not shown; 29). Finally, it is worth noting that when wild type RecA protein was over-expressed, a partial stimulation of both recombination (1.46 ± 0.13 fold) and hotspot activity (1.87 ± 0.22) was observed only for χ* (Figure 5B and C, center panel). These findings suggest that increased concentrations of RecA protein can overcome the deficiency of RecBC1004D-χ* stimulated recombination in vivo.

Discussion

Here we show that a mutant RecA protein, RecA730, which has an enhanced capacity to nucleate on ssDNA, can rescue deficiencies of a mutant RecBCD enzyme. In vitro, the yield of RecA nucleoprotein filaments assembled on χ*-containing ssDNA, produced by the processing of dsDNA with a χ* sequence by RecBC1004D enzyme, is increased. In vivo, the frequency of χ*-stimulated recombination is increased by the RecA730 protein. Previously, we found that the χ* sequence attenuated the nuclease activity of the RecBC1004D enzyme both in vivo and in vitro 29,30, and that χ*-dependent joint molecules were produced in vitro 30. However, stimulation of recombination was not detected in vivo 29. Because DNA pairing in vitro coordinated by RecBC1004D enzyme and χ* was lower than for wild type enzyme, we concluded that the failure to detect recombination in vivo resulted from the lower yield of χ*-containing nucleoprotein filaments 30. Since the RecA730 protein both nucleates faster on ssDNA and more efficiently displaces SSB protein 38,41, we reasoned that this mutant RecA protein might suppress the recombination deficiency displayed by the RecBC1004D – χ* interaction. Indeed, RecA730 protein did so.

Suppressors of mutations in the RecF pathway were discovered that mapped in recA 34–36. Subsequently, it was established that these mutant RecA proteins assembled on ssDNA faster due to an increased frequency of spontaneous nucleation; as a consequence, these mutant RecA proteins more rapidly and more fully displace SSB protein from ssDNA 38,42–47. Recently, it was shown that components of the RecF pathway can contribute to RecBCD pathway if the RecA-loading activity of the RecBCD enzyme was inactivated 11,48–50. This suppression is not restricted to the recB1080 allele, because the UV sensitivity of recB2154, recB2155, recC2145, recC1002, and recC1004, which had been measured previously in a recF− background, was also corrected by recF+ (Figure 4 and N.H. and Ichizo Kobayashi (unpublished observations)). The partial suppression of UV sensitivity by the RecF pathway can be explained by RecA-loading ability of the RecFOR complex which compensates for the lost RecA-loading capacity of certain mutant RecBCD enzymes 11,50. Consequently, we could not determine whether RecA730 could suppress the UV sensitivity of the recC1004 mutation because this mutant showed little sensitivity to UV in a recF+ background, showing that the RecF pathway makes a significant contribution to UV resistance in these cells. This result is also consistent with the original finding that recC1004 is phenotypically Rec+ in phage λ crosses (Figure 5). Thus, due to the relatively low UV sensitivity of the recC1004 strain, an effect of RecA730 on UV survival could not be detected. However, we could clearly detect suppression of the UV sensitivity of recC1004 in a recF− background. Collectively, these results suggest that the basal level of recombination in recC1004 is sufficiently high in otherwise wild type cells for most χ* and χ-like sequence-stimulated recombinational DNA repair. However, this level of recombinational repair is clearly less than that of the wild-type RecBCD enzyme, which is apparent in a recF− background. We suggest that this sensitivity arises from the reduced yield of χ (-like) ssDNA that is needed for efficient repair. This sub-optimal level of repair can be suppressed by RecA730 protein or by over-expression of wild type RecA protein, either of which results in more effective utilization of the limited χ-containing ssDNA produced.

However, the suppression of recombination in a recC1004 background by recA730 that we observed in lambda crosses involving χ* (Figure 5) cannot be due to suppression by the RecF pathway, because χ* did not stimulate recombination even in a recF+ background 29 (data not shown). Consequently, we conclude that the increased SSB-displacement capability of this mutant protein is responsible for the heightened recombination frequency. Although RecA730 suppressed the recombination defect of RecBC1004D enzyme and χ*, the suppressed level was still below that of the wild type RecBCD-canonical χ interaction in vivo simply because the yield of the processed χ*containing ssDNA is reduced.

Extending previous studies, here we demonstrated that the assembly of a RecA nucleoprotein filament, either intrinsic or loaded by RecBCD enzyme after χ recognition, is an important aspect of genetic recombination. These findings further enforce the idea that the loading of a DNA strand exchange protein by recombination mediators is a crucial aspect of recombinational DNA repair. The universality of this concept is supported by recent findings in eukaryotic recombination. The assembly of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad51 nucleoprotein filament is facilitated by Rad55/57 51, and this Rad55/57-loading can be bypassed by suppressors in Rad51 protein that acquire an enhanced capacity to displace the ssDNA binding protein, RPA 52. Also, both Rad51 nucleoprotein filament assembly and RPA-displacement are mediated by Rad52 protein 53–55. Finally, the fungal homolog of BRCA2, Ustilago maydis Brh2 protein 56, also facilitates loading of Rad51 protein onto complexes of RPA and ssDNA 57. Thus, catalysis of RecA/Rad51 nucleoprotein filament formation is an essential aspect of recombinational DNA repair.

Materials & Methods

Bacterial strains, phages and plasmids

Escherichia coli strains used were: SCK303 (a ΔrecA srl::Tn10 derivative of KK2186 58; laboratory collection), BIK1291 (= DH10B; araD139 Δ(ara, leu)7697 ΔlacX74 galU galK mcrAΔ (mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) rpsL deoR (φ80dlacZΔ M15) endA1 nupG recA1; Dr. Ichizo Kobayashi) 59, V66 (= BIK796; recF143 argA his-4 met rpsL31 λ− F− ; Dr. Ichizo Kobayashi) 28, BIK1288 (as V66, but recF+ zic::Tn10; Dr. Ichizo Kobayashi) 29, V72 (= BIK1274; as V66, but recC1004; Dr. Ichizo Kobayashi) 28, BIK1284 (as V72, but recF+ zic::Tn10; Dr. Ichizo Kobayashi) 29, V68 (= BIK2411; as V66, but recC73; Dr. Ichizo Kobayashi) 28 and BIK3738 (as BIK1288, but recC73; Dr. Ichizo Kobayashi) 29, BIK808 (= FS620; C600 λrrecB21 supE ; Dr. Ichizo Kobayashi) 29, JM1 (= FS611; recB21 recC22 sbcA20 supF; Dr. Ichizo Kobayashi) 29. Bacteriophage λ strains, LIK916 (χ0), LIK950 (χ+), LIK907 (χ*) and LIK1068, were used for the recombination crosses (Dr. Ichizo Kobayashi) 29. The recC73 mutation displays a null phenotype 28 due to truncation by a frameshift mutation at position 1938 in the recC gene 30. The mutant gene product should produce a 663 amino acid polypeptide, comprising 646 amino acids of the wild type sequence, followed by an additional 17 amino acids. Plasmid pMS421 carrying lacIq gene was described 60. Multicopy plasmids pKM100, containing a lacUV5-controlled recA gene, and pKM300, containin a T7-promoter-controlled recA gene, as well as bacteriophage M13-KM2 were described previously 61. The recA730 derivative plasmids, pSNH50 and pSNH60, were made by site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) using 2 synthetic oligonucleotides (5′-GGGTGAAGACCGTTCTATGGATGTGAAAACCATCTCTACCG and 5′-CGGTAGAGATGGTTTTCACATCCATAGAACGGTCTTCACCC) from pKM100 and pKM300, respectively. Sequencing of the entire recA gene in these plasmids confirmed that no the other mutations were present (data not shown).

Media

E. coli cells were grown in L broth (1.0% Bacto-tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract and 1.0% sodium chloride (NaCl)), or tryptone broth (1.0% Bacto-tryptone and 0.5% NaCl) supplemented with 0.2% maltose, 10 mM MgSO4, and 10 μg/ml vitamin B1. Antibiotics at the following concentrations were added when required: ampicillin (amp) at 100 μg/ml, chloramphenicol (cam) at 25 μg/ml, tetracycline (tet) at 10 μg/ml, and spectinomycin (spc) at 30 μg/ml.

Proteins and reagents

RecBCD, RecBC1004D, SSB, and wild type RecA proteins were purified as described previously 40,62–64. RecA730 protein was purified using a procedure as described 65: Plasmid pSNH60 that carries the recA730 gene downstream of the T7 promoter was introduced into SCK303. The transformant was cultured at 37 oC in L broth containing amp to mid-log phase (OD600 = 0.3). RecA protein synthesis was induced by adding M13 phage (multiplicity of infection (moi) = 10) that expressed T7 RNA polymerase, M13-KM2, together with 1 mM isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 3 hr. Cells were harvested, re-suspended in ice-cold buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 5 mM EDTA, 25% sucrose and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol) and frozen at −80 oC. After thawing, cells were lysed with 0.5 mg/ml lysozyme followed by sonication. The lysate was mixed with 0.31% Brij-58 and centrifuged with 25 krpm for 45 min. The cleared lysate was diluted with the same buffer to adjust the OD260 to 160. Polyethyleneimine (pH 8) was added to 0.5% to precipitate the nucleic acids, and then centrifuged at 10 krpm for 20 min. The pellet was suspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, 0.3 M ammonium sulphate (Am2SO4) and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, stirred for 2 hr, and then centrifuged. After the centrifugation, the supernatant was made 60% saturating by adding solid Am2SO4 and centrifuged. The pellet was suspended in a dialysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 20 mM magnesium chloride (MgCl2), 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 10% glycerol) and dialyzed over night. The precipitate was dissolved in buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM EDTA, 1 M NaCl, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 10% glycerol) and centrifuged. The supernatant was loaded onto a S-300HR column (Pharmacia Biotech; 300 ml; flow rate of 3 ml/min) equilibrated with TEM + 1M NaCl buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol and 1 M NaCl). RecA730 protein, identified by ssDNA-dependent ATPase activity and SDS-PAGE analysis, eluted as a single peak. The pooled peak fractions from the S-300HR were loaded onto EconoPack Q column (Bio-Rad; 5 ml; flow rate of 0.5 ml/min) after dialysis against TEM + 50 mM NaCl buffer; the RecA730 protein eluted in the flow through. The pool was dialyzed against buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol), solid Am2SO4 was added to 70% saturating, and the solution was centrifuged. The pellet was suspended into TEDS + 100 mM NaCl (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and 100 mM NaCl) and dialyzed against the same buffer. The solution was filtered through a 0.2 μm filter, and then loaded onto MonoQ HR10/10 column (Pharmacia Biotech; 8 ml; flow rate of 3.0 ml/min). RecA730 protein eluted at approximately 480 mM NaCl in a 360 ml linear gradient (100 – 1000 mM NaCl). The pooled protein was concentrated by dialysis against storage buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 150 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol). The concentration of RecA730 protein was determined spectrophotometrically using an extinction coefficient of 2.15 x 104 M−1 cm−1 at 278 nm.

Exonuclease I, restriction endonucleases, and T4 polynucleotide kinase were products of New England Biolabs. Shrimp alkaline phosphatase was purchased from United States Biochemical Corp. Proteinase K was purchased from Roche Molecular Biochemicals. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) was purchased from Sigma. ATP was dissolved in water at pH 7.5 and the concentration was determined spectrophotometrically using an extinction coefficient of 1.54 x 104 M−1 cm−1 at 260 nm. All chemicals were reagent grade and solutions were prepared with NanoPure Water.

Substrate DNA for biochemical analysis

Plasmids pBR322, pNH92 and pNH94 30 were purified using a Qiagen kit and digested by a restriction endonuclease, AvaI, following a reaction with shrimp alkaline phosphatase for removal of phosphoryl groups. After the 5′-end of the linear dsDNA was labeled by T4 polynucleotide kinase with 32P, unincorporated [γ-32P]ATP was removed by passage through a MicroSpin S-200 HR column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Exonuclease I protection assay and quantification of χ-specific fragment production

The procedure described previously was followed 10,39 except that ATPγ-S was omitted. Reactions contained 25 mM Tris-acetate (pH 7.5), 8 mM magnesium acetate, 5 mM ATP, 1 mM DTT, 10 μM nucleotide linear dsDNA, 5 μM either wild-type RecA or RecA730 protein, 4 μM SSB protein, and either 0.1 nM RecBCD or 0.2 nM RecBC1004D enzyme. Reactions (37 oC) were started by addition of RecBCD enzyme. After 3 min, poly(dT) (50 μM nucleotide) was added to sequester the free RecA protein. After 2 min of further incubation, an aliquot was taken (representing time zero) and then exonuclease I was added to a final concentration of 100 U/ml and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Control reactions contained heat-denatured DNA instead of dsDNA processed by RecBCD enzyme or, in the case of the uncoupled reactions, RecA protein was added 3 min after addition of RecBCD enzyme. Aliquots were added to stop solution (40 mM EDTA, 0.8% SDS, 1.5 μg/μl proteinase K and 0.04% BPB) at the indicated times after exonuclease I addition, and were analyzed by agarose gel (1.0 % (w/v)) electrophoresis. Production of χ-specific fragments was quantified by using a Molecular Dynamics STORM 870 PhosphorImager and ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics). The percentages were calculated relative to the initial amount of the substrate. Standard deviations were performed using GraphPad Prism version 4.02 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego California USA, www.graphpad.com. In all graphs, points represent the mean and the error bars are the standard deviation.

UV sensitivity measurement

Exponentially growing cultures (in L broth with amp and spc for selection of plasmid and IPTG to express the recA gene) were diluted into M9 medium 66 and spread on L agar plates. The plates were irradiated with UV light (254 nm) for various doses (times). Colonies were scored after incubation at 37 oC for 20 hr in the dark.

Lambda phage recombination assay

The experimental design is shown in Figure 5A. The procedure described previously was followed 29: Parental phages (both LIK916, 950 or 907 and LIK1068) were mixed together before infection of pre-warmed E. coli host cells. Infection was carried out at moi = 5 for each phage. After a cycle, S+ - Jh recombinant phages were counted by plating on BIK808 and total phages were measured by plating on JM1. The recombination frequency (%) was calculated as [recombinant phage titer/total phage titer] x 100 and the hotspot activity was assessed by the ratio, turbid plaque number/clear plaque number, four the recombinant phages plated on BIK808.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Katsumi Morimatsu for the RecA expression plasmids, advice regarding purification of the mutant RecA protein, and helpful discussion, and Dr. Ichizo Kobayashi for bacteria and phage strains. We are grateful to the members of the Kowalczykowski laboratory, Andrei Alexeev, Aura Carreira, Clarke Conant, Roberto Galletto, Katsumi Morimatsu, Amitabh Nimonkar, Behzad Rad, Edgar Valencia-Morales, Jason Wong, and Liang Yang for their critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health GM-41347 to S. C. K., the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Postdoctoral Fellowship for Research Abroad, and “Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research” from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (17049008, and 1770001) to N. H.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kowalczykowski SC, Dixon DA, Eggleston AK, Lauder SD, Rehrauer WM. Biochemistry of homologous recombination in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:401–465. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.401-465.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spies M, Kowalczykowski SC. Homologous recombination by RecBCD and RecF pathways. In: Higgins NP, editor. The Bacterial Chromosome. ASM Press; Washington, D.C.: 2005. pp. 389–403. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dillingham MS, Spies M, Kowalczykowski SC. RecBCD enzyme is a bipolar DNA helicase. Nature. 2003;423:893–7. doi: 10.1038/nature01673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bianco PR, Kowalczykowski SC. The recombination hotspot Chi is recognized by the translocating RecBCD enzyme as the single strand of DNA containing the sequence 5′-GCTGGTGG-3′. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:6706–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixon DA, Kowalczykowski SC. Homologous pairing in vitro stimulated by the recombination hotspot, Chi. Cell. 1991;66:361–71. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90625-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon DA, Kowalczykowski SC. The recombination hotspot χ is a regulatory sequence that acts by attenuating the nuclease activity of the E. coli RecBCD enzyme. Cell. 1993;73:87–96. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90162-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson DG, Kowalczykowski SC. The recombination hot spot χ is a regulatory element that switches the polarity of DNA degradation by the RecBCD enzyme. Genes Dev. 1997;11:571–81. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spies M, Bianco PR, Dillingham MS, Handa N, Baskin RJ, Kowalczykowski SC. A molecular throttle: the recombination hotspot χ controls DNA translocation by the RecBCD helicase. Cell. 2003;114:647–54. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00681-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Handa N, Bianco PR, Baskin RJ, Kowalczykowski SC. Direct visualization of RecBCD movement reveals cotranslocation of the RecD motor after χ recognition. Mol Cell. 2005;17:745–50. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson DG, Kowalczykowski SC. The translocating RecBCD enzyme stimulates recombination by directing RecA protein onto ssDNA in a χregulated manner. Cell. 1997;90:77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnold DA, Kowalczykowski SC. Facilitated loading of RecA protein is essential to recombination by RecBCD enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:12261–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.12261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amundsen SK, Taylor AF, Smith GR. The RecD subunit of the Escherichia coli RecBCD enzyme inhibits RecA loading, homologous recombination, and DNA repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7399–404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130192397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Churchill JJ, Kowalczykowski SC. Identification of the RecA protein-loading domain of RecBCD enzyme. J Mol Biol. 2000;297:537–542. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spies M, Kowalczykowski SC. The RecA binding locus of RecBCD is a general domain for recruitment of DNA strand exchange proteins. Mol Cell. 2006;21:573–80. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singleton MR, Dillingham MS, Gaudier M, Kowalczykowski SC, Wigley DB. Crystal structure of RecBCD enzyme reveals a machine for processing DNA breaks. Nature. 2004;432:187–93. doi: 10.1038/nature02988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chédin F, Handa N, Dillingham MS, Kowalczykowski SC. The AddAB helicase/nuclease forms a stable complex with its cognate χ sequence during translocation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18610–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600882200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Handa N, Ichige A, Kusano K, Kobayashi I. Cellular responses to postsegregational killing by restriction-modification genes. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2218–29. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.8.2218-2229.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnold DA, Kowalczykowski SC. Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. Nature Publishing Group; London: 1999. RecBCD helicase/nuclease.http://www.els.net [Google Scholar]

- 19.Handa N, Kobayashi I. Accumulation of large non-circular forms of the chromosome in recombination-defective mutants of Escherichia coli. BMC Mol Biol. 2003;4:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seigneur M, Bidnenko V, Ehrlich SD, Michel B. RuvAB acts at arrested replication forks. Cell. 1998;95:419–430. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81772-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miranda A, Kuzminov A. Chromosomal lesion suppression and removal in Escherichia coli via linear DNA degradation. Genetics. 2003;163:1255–71. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.4.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blattner FR, Plunkett G, 3rd, Bloch CA, Perna NT, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner JD, Rode CK, Mayhew GF, Gregor J, Davis NW, Kirkpatrick HA, Goeden MA, Rose DJ, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–74. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chédin F, Kowalczykowski SC. A novel family of regulated helicases/nucleases from Gram-positive bacteria: insights into the initiation of DNA recombination. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43:823–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith GR, Roberts CM, Schultz DW. Activity of Chi recombinational hot spots in Salmonella typhimurium. Genetics. 1986;112:429–439. doi: 10.1093/genetics/112.3.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biswas I, Maguin E, Ehrlich SD, Gruss A. A 7-base-pair sequence protects DNA from exonucleolytic degradation in Lactococcus lactis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:2244–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chédin F, Noirot P, Biaudet V, Ehrlich SD. A five-nucleotide sequence protects DNA from exonucleolytic degradation by AddAB, the RecBCD analogue of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1369–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sourice S, Biaudet V, El Karoui M, Ehrlich SD, Gruss A. Identification of the Chi site of Haemophilus influenzae as several sequences related to the Escherichia coli Chi site. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:1021–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schultz DW, Taylor AF, Smith GR. Escherichia coli RecBC pseudorevertants lacking Chi recombinational hotspot activity. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:664–680. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.2.664-680.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Handa N, Ohashi S, Kusano K, Kobayashi I. Chi-star, a chi-related 11-mer sequence partially active in an E. coli recC1004 strain. Genes Cells. 1997;2:525–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1997.1410339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arnold DA, Handa N, Kobayashi I, Kowalczykowski SC. A novel, 11 nucleotide variant of χ, χ*: one of a class of sequences defining the Escherichia coli recombination hotspot χ. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:469–79. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lam ST, Stahl MM, McMilin KD, Stahl FW. Rec-mediated recombinational hot spot activity in bacteriophage lambda. II A mutation which causes hot spot activity. Genetics. 1974;77:425–33. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.3.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kushner SR, Nagaishi H, Clark AJ. Indirect suppression of recB and recC mutations by exonuclease I deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1972;69:1366–1370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.6.1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morimatsu K, Kowalczykowski SC. RecFOR proteins load RecA protein onto gapped DNA to accelerate DNA strand exchange: a universal step of recombinational repair. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1337–47. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Volkert MR, Margossian LJ, Clark AJ. Two component suppression of recF143 by recA441 in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:702–705. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.2.702-705.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang TC, Smith KC. recA (Srf) suppression of recF deficiency in the postreplication repair of UV-irradiated Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:940–6. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.2.940-946.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang TCV, Chang HY, Hung JL. Cosuppression of recF, recR and recO mutations by mutant recA alleles in Escherichia coli cells. Mutat Res. 1993;294:157–66. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(93)90024-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Madiraju MV, Templin A, Clark AJ. Properties of a mutant recA-encoded protein reveal a possible role for Escherichia coli recF-encoded protein in genetic recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:6592–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lavery PE, Kowalczykowski SC. Biochemical basis of the constitutive repressor cleavage activity of recA730 protein. A comparison to recA441 and recA803 proteins. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:20648–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Churchill JJ, Anderson DG, Kowalczykowski SC. The RecBC enzyme loads RecA protein onto ssDNA asymmetrically and independently of chi, resulting in constitutive recombination activation. Genes Dev. 1999;13:901–11. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arnold DA, Bianco PR, Kowalczykowski SC. The reduced levels of χ recognition exhibited by the RecBC1004D enzyme reflect its recombination defect in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16476–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Madiraju MVVS, Lavery PE, Kowalczykowski SC, Clark AJ. Enzymatic properties of the RecA803 protein, a partial suppressor of recF mutations. Biochemistry. 1992;31:10529–10535. doi: 10.1021/bi00158a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lavery PE, Kowalczykowski SC. Biochemical basis of the temperature-inducible constitutive protease activity of the RecA441 protein of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1988;203:861–74. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lavery PE, Kowalczykowski SC. Properties of recA441 protein-catalyzed DNA strand exchange can be attributed to an enhanced ability to compete with SSB protein. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:4004–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Madiraju MVVS, Clark AJ. Use of recA803, a partial suppressor of recF, to analyze the effects of the mutant Ssb (single-stranded DNA-binding) proteins in vivo and in vitro. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;224:129–135. doi: 10.1007/BF00259459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Madiraju MVVS, Clark AJ. Evidence for ATP binding and double-stranded DNA binding by Escherichia coli RecF protein. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7705–10. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.23.7705-7710.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kowalczykowski SC. Biochemical and biological function of Escherichia coli RecA protein: Behavior of mutant RecA proteins. Biochimie. 1991;73:289–304. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(91)90216-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kowalczykowski SC. Biochemistry of genetic recombination: Energetics and mechanism of DNA strand exchange. Annu Rev Biophys Biophys Chem. 1991;20:539–575. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.20.060191.002543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ivancic-Bace I, Peharec P, Moslavac S, Skrobot N, Salaj-Smic E, Brcic-Kostic K. RecFOR Function Is Required for DNA Repair and Recombination in a RecA Loading-Deficient recB Mutant of Escherichia coli. Genetics. 2003;163:485–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.2.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Amundsen SK, Smith GR. Interchangeable parts of the Escherichia coli recombination machinery. Cell. 2003;112:741–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anderson DG, Churchill JJ, Kowalczykowski SC. A single mutation, RecB(D1080A), eliminates RecA protein loading but not Chi recognition by RecBCD enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27139–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.27139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sung P. Yeast Rad55 and Rad57 proteins form a heterodimer that functions with replication protein A to promote DNA strand exchange by Rad51 recombinase. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1111–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.9.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fortin GS, Symington LS. Mutations in yeast Rad51 that partially bypass the requirement for Rad55 and Rad57 in DNA repair by increasing the stability of Rad51-DNA complexes. EMBO J. 2002;21:3160–70. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sung P. Function of yeast Rad52 protein as a mediator between replication protein A and the Rad51 recombinase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28194–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.New JH, Sugiyama T, Zaitseva E, Kowalczykowski SC. Rad52 protein stimulates DNA strand exchange by Rad51 and replication protein A. Nature. 1998;391:407–10. doi: 10.1038/34950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shinohara A, Ogawa T. Stimulation by Rad52 of yeast Rad51-mediated recombination. Nature. 1998;391:404–7. doi: 10.1038/34943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kojic M, Kostrub CF, Buchman AR, Holloman WK. BRCA2 homolog required for proficiency in DNA repair, recombination, and genome stability in Ustilago maydis. Mol Cell. 2002;10:683–91. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00632-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang H, Li Q, Fan J, Holloman WK, Pavletich NP. The BRCA2 homologue Brh2 nucleates RAD51 filament formation at a dsDNA-ssDNA junction. Nature. 2005;433:653–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zagursky RJ, Berman ML. Cloning vectors that yield high levels of single-stranded DNA for rapid DNA sequencing. Gene. 1984;27:183–91. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grant SG, Jessee J, Bloom FR, Hanahan D. Differential plasmid rescue from transgenic mouse DNAs into Escherichia coli methylation-restriction mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4645–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heath JD, Weinstock GM. Tandem duplications of the lac region of the Escherichia coli chromosome. Biochimie. 1991;73:343–52. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(91)90099-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morimatsu K, Horii T. Analysis of the DNA binding site of Escherichia coli RecA protein. Adv Biophys. 1995;31:23–48. doi: 10.1016/0065-227x(95)99381-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roman LJ, Kowalczykowski SC. Characterization of the helicase activity of the Escherichia coli RecBCD enzyme using a novel helicase assay. Biochemistry. 1989;28:2863–2873. doi: 10.1021/bi00433a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.LeBowitz J. Biochemical mechanism of strand initiation in bacteriophage lambda DNA replication PhD. Johns Hopkins University; Baltimore, MD: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mirshad JK, Kowalczykowski SC. Biochemical basis of the constitutive coprotease activity of RecA P67W protein. Biochemistry. 2003;42:5937–44. doi: 10.1021/bi027232q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morimatsu K, Horii T. The DNA-binding site of the RecA protein. Photochemical cross-linking of Tyr103 to single-stranded DNA. Eur J Biochem. 1995;228:772–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Second Edition. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]