Worldwide concern about the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) pandemic in Africa is justified, but it should not overshadow the need for treatment of other diseases. Infectious diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, and even polio continue to pose major health risks for the 10% of the world's population who live in Africa. Cardiovascular disease is a growing threat to health in Africa, accounting for 9.2% of deaths in 2001, principally due to hypertension, stroke, cardiomyopathy, and rheumatic valve disease.1,2 Cardiovascular disease has a higher mortality rate in developing countries and affects younger people and women disproportionately. Peripartum cardiomyopathy is a major cause of heart failure in Africa. In some parts of Nigeria, heart failure in women is reported to occur after childbirth as often as once in every 100 births.3 Although ischemic heart disease is relatively uncommon in Africa, rheumatic valvular disease remains a commonly encountered cause of disability and death, and pericardial disease may be the first manifestation of HIV infection in its early stages. Aneurysms can also be associated with HIV. Worldwide surveys have found that congenital heart disease may occur in 12 to 15 of 1,000 live births and that it is often associated with high infant mortality rates.4

Meeting the healthcare needs of Africans is an enormous challenge. The World Health Organization (WHO) lists sub-Saharan Africa as one of the geographic areas least served by healthcare providers (doctors, nurses, and midwives).5 Socioeconomic barriers to cardiovascular care in Africa have included inadequate financing, lack of education of health workers, and poor laboratory support. Besides, poverty, political instability, and corruption exist in many parts of Africa today.

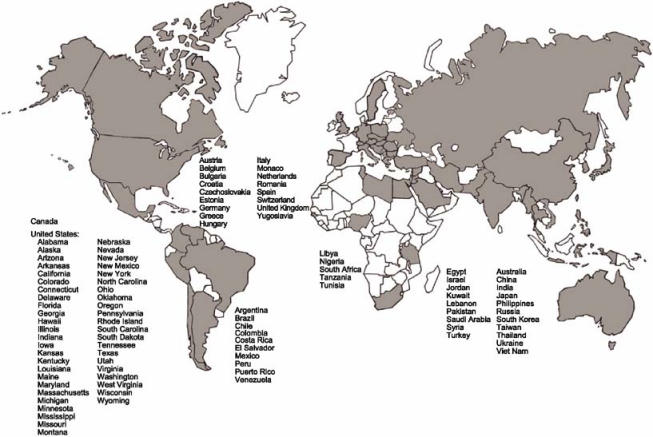

The Texas Heart® Institute was established in 1962 to foster excellence in cardiovascular care through education, research, and patient care. Over the past 45 years, the Texas Heart Institute has trained physicians and surgeons from all regions of the world (Fig. 1). In the current issue of the Texas Heart Institute Journal, Dr. John Eze, a recent graduate of our fellowship program, reports on the history and challenges encountered in establishing a program for cardiac surgery in Nigeria.6 Specifically, Dr. Eze relates the clinical experience of the cardiothoracic program in Enugu, Nigeria. More broadly, he talks candidly about the economic and social obstacles to health care in the country at large.

Fig. 1 Countries of origin of Texas Heart Institute trainees in cardiology and cardiovascular surgery.

Located in West Africa, Nigeria is slightly larger than twice the size of California and has a population of over 130 million people, or approximately 1 of every 6 Africans. That's the largest population in Africa; but 66% of the population falls below the poverty line of $1 in income per day. In fact, Nigeria is among the 20 poorest countries in the world, despite being the world's 5th-largest oil producer. Life expectancy is around 50 years. The prevalence of HIV was 5% in 2003, with 3.3 million people infected. In 2005, AIDS caused an estimated 220,000 deaths in Nigeria and left 930,000 orphans. Ten percent of HIV infections were attributed to blood transfusions.

Despite the complex challenges posed by disease in the African continent, there is hope for improvement of health care. Polio remains endemic in some countries in Africa, and northern Nigeria reports the largest number of active cases in the world. To eradicate polio, the WHO in 2004 began the mass immunization of 63 million children in 10 countries in west and central Africa. Studies in Nigeria have suggested that effective treatment of hypertension could avert 2 out of 5 deaths caused by that disorder, a reduction over 10 times that now observed in the United States.7 International health organizations, in cooperation with governments in Africa, have attracted funding for the screening and treatment of diseases, including hypertension and HIV infections.

It is hoped that one day the people of Africa will be able to receive appropriate cardiovascular care in their own countries. We are indebted to Drs. Eze and Ezemba for bringing this important topic to our attention. We invite them to report their experience with cardiovascular care in Nigeria over the next 5 years. We trust that improvements will be forthcoming, and we applaud these physicians for their dedication and commitment to the health care and well-being of their fellow citizens.

James J. Livesay, MD

Cardiac Surgeon, Texas Heart Institute at St. Luke's Episcopal Hospital, Houston

References

- 1.Kadiri S. Tackling cardiovascular disease in Africa. BMJ 2005; 331:711–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Opie LH, Mayosi BM. Cardiovascular disease in sub-Saharan Africa. Circulation 2005;112:3536–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Sliwa K, Damasceno A, Mayosi BM. Epidemiology and etiology of cardiomyopathy in Africa. Circulation 2005;112:3577–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Aburawi EH. The burden of congenital heart disease in Libya. Libyan J Med, AOP:060902 (published 8 September 2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Ntsekhe M, Hakim J. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus infection on cardiovascular disease in Africa. Circulation 2005;112:3602–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Eze JC, Ezemba N. Open-heart surgery in Nigeria: indications and challenges. Tex Heart Inst J 2007;34:8–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Cooper RS, Rotimi CN, Kaufman JS, Muna WF, Mensah GA. Hypertension treatment and control in sub-Saharan Africa: the epidemiological basis for policy. BMJ 1998;316:614–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]