Abstract

Objective

Client satisfaction with mental health services is used commonly as an indicator of the quality of care, but there is minimal research on the construct of client satisfaction in youth services, and the extent to which satisfaction is related to improvements in clinical functioning versus other determinants. We examined the relationship between parent and youth satisfaction with youth services, and tested for significant determinants of satisfaction across three major domains: (1) change in youth clinical functioning; (2) youth/family service entry characteristics; (3) treatment/therapist characteristics.

Method

The participants were 143 youths receiving community-based out-patient care. Youths and parents were interviewed at service entry and six months later using well-established measures of clinical functioning and service satisfaction.

Results

Youths and parents reported generally high satisfaction, but the correlation between them was low. Despite testing for many potential predictors of satisfaction, very few significant effects were found. In regression analyses of significant predictors of satisfaction, higher youth satisfaction was significantly associated with Caucasian ethnicity and more positive youth expectations about treatment. Higher parent satisfaction was associated with lower caregiver strain at service entry, increased number of sessions, and improvement in youth-reported functional impairment.

Conclusions

Keywords: Client satisfaction, youth psychotherapy, outcomes

Introduction

Measurement of consumer satisfaction with mental health services is ubiquitous in many publicly and privately-funded mental health care systems. In an increasingly competitive market, with greater pressure on providers to measure outcomes, assessing consumer satisfaction is a relatively inexpensive and efficient way to generate data on service quality (Edlund et al., 2003; Lambert et al., 1998). Measurement of consumer satisfaction is also consistent with broader trends in health care emphasizing the importance of consumer input on health care decision-making and evaluation (Kessler & Mroczek, 1995). However, despite its common use, limited research exists on the construct of client satisfaction. For example, in a comprehensive recent review of youth psychotherapy outcome research, Weisz and colleagues (2005) found that only 7.6% of 236 studies included some measurement of satisfaction. This lack of empirical attention to a common "real world" construct is another example of the oft-cited gap between research and practice of mental health services.

There is considerable ambiguity about the meaning of consumer satisfaction with mental health services and in particular, the extent to which satisfaction is associated with other types of clinical outcomes such as change in patients' symptom severity and/or functional impairment (Edlund et al., 2003; Garland et al., 2003; Lambert et al., 1998). Some research suggests that consumer satisfaction is not strongly related to improvements in clinical outcomes (Garland et al., 2003; Kaplan et al., 2001; Lambert et al., 1998; Pekarkik & Guidry, 1999), whereas other research indicates that clinical outcomes are important determinants of mental health consumer satisfaction (Fontana & Rosenheck, 2001; Fontana et al., 2003; Liao & Sukumar, 2005). Relatively less research has been conducted on the measurement of consumer satisfaction with youth mental health services, and there are no well-developed theoretical models to guide investigation of the satisfaction construct. Youth service satisfaction is also complicated by the two potential consumers, youth and parent. Greater exploration of the satisfaction construct is needed within the youth mental health services field given the construct's widespread use and its potential influence in evaluating the effectiveness and/or quality of mental health services.

Consumer satisfaction data are often used in policy and funding arenas and included in health care accreditation reviews (Lambert et al., 1998; Rosenblatt et al., 1998; Salzer, 1999). In fact, satisfaction data often serve as the only indicator of the quality of mental health services (Bickman, 2000). These data have strong face validity and may be more easily interpretable than more complex, longitudinal, repeated measures of clinically significant change. Thus, consumer satisfaction has popular appeal. In a survey of behavioral health care organization representatives, Bilbrey and Bilbrey (1995) reported that organization representatives judged customer satisfaction to be the most helpful of all measures of outcomes. Ten years later, we conducted an informal brief telephone survey of the ten largest behavioral health care organizations in the United States and confirmed that all ten use consumer satisfaction data. Our State Department of Mental Health also collects consumer satisfaction data for adult and youth publicly funded services for use in fiscal and policy decision-making in mental health, and this is likely not unique to California. Consumer satisfaction ratings may be assumed to be a "proxy" indicator of the effectiveness of care, but if satisfaction is not strongly associated with changes in other clinical outcomes, what does it represent and to what extent is it influenced by the actual care received?

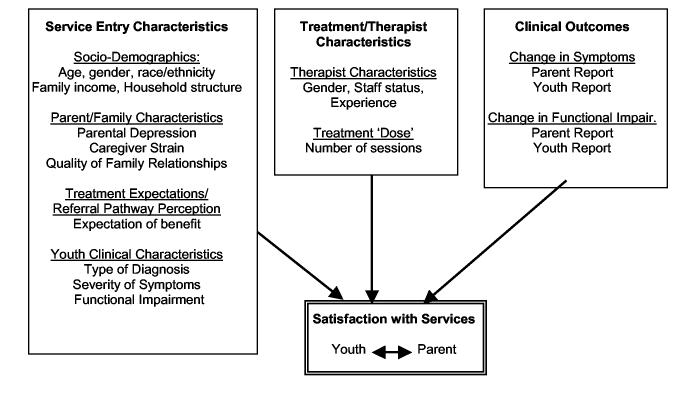

Figure 1 presents a heuristic model of potential determinants of client satisfaction with mental health services examined in this study. Preliminary research suggests that consumer satisfaction for child and adolescent services may be driven largely by factors predetermined at entry into treatment (Garland et al., 2000a). These factors include severity of symptoms at entry, expectations about services, and referral pathways into treatment (Garland et al., 2000a; Godley et al., 1998; Lebow, 1983). Specifically, several studies have found that more severe psychiatric symptomotology at service entry is associated with poorer service satisfaction (Garland et al., 2000a; Godley et al., 1998). More positive expectations about treatment at service entry have been associated with greater satisfaction (Garland et al., 2000a; Rosen et al., 1994), while the perception of coercive referral into treatment has been associated with poorer satisfaction (Garland et al., 2000a; Martin et al., 2003). Other factors that have been shown to be associated with satisfaction with youth mental health services include patient socio-demographic characteristics such as race/ethnicity, age, gender, family composition, and socio-economic status (Heflinger et al., 2004; Shapiro et al., 1997); however, several studies have not found a significant relationship between these types of variables and satisfaction (e.g., Garland et al., 2000a; Martin et al., 2003).

Figure 1.

Potential Determinants of Satisfaction with Youth Mental

In this study we will also test the significance of the relationship between satisfaction and the treatment and therapist characteristics listed in Figure 1, including therapist experience and number of treatment sessions. Finally, we will examine the extent to which variation in consumer satisfaction is accounted for by change in clinical outcomes (e.g., symptoms and functioning according to both informants) as indicated in Figure 1. Mixed results on these relationships were reviewed earlier in the introduction.

Many studies of consumer satisfaction with mental health services suffer from methodological limitations. For studies of youth service satisfaction, methodological limitations include unacceptable or untested psychometrics of the satisfaction measure itself (often including negatively skewed data with limited variance) and/or low response rates, which suggest sample selection biases (Young et al., 1995). Child service satisfaction also presents the additional challenge of multiple informants. Some research has focused on parents' satisfaction with their children's care (Bradley & Clark, 1993; Heflinger et al., 2004), whereas other research has focused on youths' satisfaction with their own care (Garland et al., 2003; Shapiro et al., 1997). Only a few studies have examined both perspectives simultaneously and most have reported that the two informants' satisfaction ratings are only minimally to moderately correlated (Kaplan et al., 2001; Lambert et al., 1998; Loff et al., 1987). In addition, with a few exceptions (Garland et al., 2003; Lambert et al., 1998), most studies of youth service satisfaction have been cross-sectional, prohibiting an investigation of the extent to which prospectively measured change in symptoms, functioning and/or characteristics assessed at service entry are associated with satisfaction. The present study addresses these methodological limitations by using measures of consumer satisfaction with established psychometric properties and adequate variance, achieving a high response rate for a diverse sample of youths and parents from community-based psychiatric clinics, and prospectively measuring symptoms and functioning change with well-established measures.

The aims of this study are to examine the extent to which youth and parent reports of satisfaction with community-based youth psychotherapy are associated with: (a) each other; (b) youth and parent reports of change in clinical outcomes, (c) child, parent, and family characteristics at service entry, and (d) characteristics of the psychotherapy itself and the therapist. We also examine the extent to which each report of satisfaction is accounted for by significant factors across these domains (b through d above).

Method

Participants

Youth and parent participants

The participants in the current study are from a larger study of youths who received publicly-funded, out-patient mental health treatment in one of two large community-based clinics in San Diego County between May 2000 and April 2003. Youths with all clinician-assigned DSM-IV diagnoses were included to obtain a representative sample of youths receiving publicly-funded mental health services in San Diego, with the exception of individuals with significant mental retardation or acute psychotic thought processes limiting their ability to complete the study questionnaires. Only English-speaking youths entering treatment for the first time or for a new "episode" of care (i.e., after at least six months without mental health treatment) were included.

Participants were recruited into the study consecutively as they entered a new episode of treatment in either of the clinics. Of the 223 families solicited for participation, 170 (76%) consented to participate. Reasons cited not to participate included "too busy" (n=18) and "no interest" (n=12). The current sample consists of the 143 youth and parent participants who had complete data on all study measures (except the CBCL/YSR scales which were omitted for 24 parents and 24 youths due to an administrative error at the clinic sites; 112 (78%) of the 143 families had complete CBCL/YSR data at both baseline and follow-up). Sixty-two percent of youths (n=89) were males and 38% (n=54) were females ages 11 to 18 (M = 13.5; SD = 2.0). Forty-five (n=64) percent of youths self-identified as Caucasian; 18% (n=25) Latino; 13% (n=19) African American; and 25% (n=35) mixed or other racial/ethnic background. The parents interviewed were 92% (n=131) mothers or other female caregivers and 8% (n=12) fathers or other male caregivers. Twenty-nine percent (n=42) of the families reported an annual family income of less than $15,000; 37% (n=52) between $15,000 and $45,000; and 34% (n=49) more than $45,000.

Overall, study participants did not differ from non-participants on demographics (mean age, gender distribution, race/ethnicity) or on baseline clinical characteristics (CBCL Total Behavior Problems T-score) (Boxmeyer, 2004). In addition, study participants did not differ from the total population of youths receiving publicly-funded mental health services in the entire county on mean age, gender distribution, race/ethnic distribution, or mean CBCL Total Behavior Problems T-score (Baker et al., 2003), except that Latino families were slightly under-represented among participants (likely due to the requirement that study participants speak English fluently). Study retention rates were strong with 93% (n=157) of the total sample participating at six-month follow-up. Those lost to follow-up did not differ from participants on basic demographic or clinical characteristics. In addition, the subsample of 143 participants included in the current study was not significantly different from the excluded participants on demographic or child clinical variables at baseline.

Clinician participants

A total of 55 clinicians provided treatment at baseline to participating families in one of two publicly-funded youth mental health clinic systems in the region. The clinicians were 76% (n=42) females and 24% (n=13) males. Fifty-eight percent (n=32) self-identified as Caucasian, 18% (n=10) Latino, 4% (n=2) African American, and 20% (n=8) mixed or other racial/ethnic background. Twenty-seven percent (n=15) had attained doctoral level degrees (PhD, PsyD, MD), 44% (n=24) held master's level degrees (MSW, MFCC, MA), and 29% (n=15) held bachelor's level degrees (BA, BS). Forty-two percent (n=23) were staff members, while 58% (n=32) were trainees. Professional disciplines included psychiatry (24%; n=13), psychology (18%; n=11), social work (22%; n=13), and marriage and family therapy (36%; n=20). There were staff members and trainees in all discipline groups.

Procedure

Baseline measures were collected during in-person interviews at the family's home or at the research site, depending on family preference. Baseline interviews were usually conducted after the first treatment session, but never after more than two sessions. Follow-up measures were obtained via in-person interviews six months later, regardless of whether the youth was still receiving mental health treatment. The six-month interval was selected because it is a relatively common interval presumed to be enough time to observe change in clinical outcomes for this clinical population (Robbins et al., 2001). Informed written and verbal consent and assent was obtained prior to the interview from all participants and they were compensated minimally for their time. The study was approved by the University of California, San Diego and the Children's Hospital and Health Center, San Diego human subjects protection committees.

Measures

Satisfaction with youth psychotherapy

The Multidimensional Adolescent Satisfaction Scale (MASS; Garland et al., 2000a; 2000b) was used to assess youth satisfaction with psychotherapy at six-month follow-up. This 21-item self-report instrument has adequate internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha=.89 in the current sample) and strong test-retest reliability (r = .88 with a 1- to 2-week retest interval) has been demonstrated in a sample of adolescents in out-patient care (Garland et al., 2000a). Construct and divergent validity of the MASS have been demonstrated with similar treatment samples (Garland et al., 2000a, 200b). The well-established Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8; Larsen et al., 1979) was used to assess parent satisfaction at six-month follow-up. Cronbach's alpha was equal to .92 in the current sample.

Child clinical characteristics

Youth symptoms were assessed at baseline and follow-up utilizing the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach 1991a) and Youth Self Report (YSR; Achenbach 1991b), which are commonly-used measures of youth mental health problems with well-established reliability and validity. The Vanderbilt Functioning Index (VFI; Bickman et al., 1998) was used to assess youth and parent report of youth functional impairment. Reliability estimates using Cronbach's alpha for parent and youth reports of the VFI at baseline were.75 and .76 for parents and youth, respectively, and the VFI has exhibited adequate validity (Bickman et al., 1998). Clinician-assigned diagnoses of externalizing disorders (ADHD, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, and/or Conduct Disorder), mood disorders, and anxiety disorders were recorded at baseline.

Service entry characteristics

Parent report on youth age, youth gender, youth ethnicity (Caucasian vs. other), household structure (single vs. two-parent family), parent gender, and family income were assessed at baseline.

Parent/family characteristics

Parent/family characteristics at baseline were measured with several assessment tools. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) was used to assess parental depression symptoms (baseline Cronbach's alpha=.93). The CES-D has demonstrated validity in the general population across diverse racial/ethnic groups (Radloff, 1977). The Caregiver Strain Questionnaire (CSQ; Brannan et al., 1997) was used to assess the impact of caring for a child with emotional or behavior problems. The CSQ has demonstrated adequate validity (McCabe et al., 2003) and exhibited a Cronbach's alpha at baseline of .91. The Family Relationship Index subscale of the Family Environment Scale (FRI; Holaham & Moos, 1983) was used to assess the quality of family relationships based on both parent and youth report. The FRI has demonstrated good construct validity (Hoge et al., 1989), and reliability estimates for parent and youth reports of the FRI at baseline were .75 and .70, respectively.

Service expectations

At the baseline interview, parents and youths responded to two items assessing the degree to which they expected mental health treatment to be (a) a waste of time, and (b) to help with the youth's problems. These response choices ranged from "Strongly Disagree" to "Strongly Agree" on a 4-point scale. The two items were summed for each reporter after reverse scoring item (a).

Treatment characteristics

Clinicians were asked to report on their ethnicity, gender, status (trainee vs. staff), and years of experience at baseline. In addition, the number of sessions was assessed at six-month follow-up using billing data.

Data Analysis

To examine the amount of variation in client satisfaction that is accounted for by change in (a) clinical outcomes, (b) factors predetermined at service entry, and (c) characteristics of the treatment itself, two sets of analyses were conducted. Prior to conducting the analyses examining potential determinants of satisfaction, change scores were computed to represent change in clinical outcomes from baseline to six-month follow-up by subtracting the six-month follow-up score from the baseline score for each measure. Although there is controversy regarding the use of change scores (also known as simple gain scores), there is support for use of this method for this purpose (Williams & Zimmerman, 1996; Zimmerman & Williams, 1998) and they have been used in well established evaluations of outcomes in children's mental health services (Lambert et al., 1998).

The first analyses consisted of computing zero-order correlations between youth and parent reports of satisfaction and each of the variables of interest within the categories cited above (a-c). Second, variables that yielded a significant correlation with satisfaction were entered into a hierarchical regression model to assess both unique prediction and total variance accounted for by the set of robust predictors. Variables determined at service entry and characteristics of treatment were entered in the first step, followed by clinical change variables.

Results

Descriptive Data

Descriptive data are reported in Tables 1a and 1b. The mean item scores on the parent and youth satisfaction measures were equivalent (3.2 on 4 point scales), representing positive satisfaction with care for each informant. The correlation between youth and parent satisfaction was modest in magnitude but statistically significant (r = .26; p < .01). Given this minimal association, separate analyses were conducted to examine determinants of youth and parent satisfaction. Examination of the distributions of the continuous variables in the study indicated problematic skewness/kurtosis for the baseline youth report on the VFI and years of clinician experience (see Table 1a). A square root transformation of the baseline youth-reported VFI yielded an adequate skewness and kurtosis (-.21 and -.06, respectively) and was used in subsequent analyses including that variable. A natural log transformation of the years of clinician experience yielded an adequate skewness and kurtosis (-.43 and 1.07, respectively) and was used in subsequent analyses including that variable.

Table 1a.

Descriptives of All Baseline Study Variables (n=143)

| Variable | M (SD) or % | Range | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Youth Age | 13.47(1.96) | 11 to 18 | 0.36 | -0.96 |

| Youth Gender | ||||

| Male | 62.2% (n=89) | |||

| Female | 37.8% (n=54) | |||

| Youth Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 44.8% (n=64) | |||

| Other | 55.2% (n=79) | |||

| Parent Gender | ||||

| Male | 8.4% (n=12) | |||

| Female | 91.6% (n=131) | |||

| Family Income | 2.55 (1.24) | 1 to 4 | -0.03 | -1.62 |

| Youth Clinical Functioning | ||||

| CBCL Total T-Score - Parenta | 67.24 (9.56) | 41 to 87 | -0.38 | -0.56 |

| YSR Total T-Score - Youtha | 56.68 (13.75) | 24 to 95 | 0.01 | -0.30 |

| VFI Mean Item Score - Parent | 0.30 (0.17) | 0 to 1 | 0.16 | -0.46 |

| VFI Mean Item Score - Youth | 0.22 (0.18) | 0 to 1 | 1.35 | 2.37 |

| Externalizing Diagnosis - Clinicianb | 49.0% (n=70) | |||

| Mood Diagnosis - Clinicianb | 46.9% (n=67) | |||

| Anxiety Diagnosis - Clinicianb | 12.6% (n=18) | |||

| Parent/Family Characteristicsa | ||||

| FRI Mean Item Score - Parent | 0.58 (0.18) | 0 to 1 | -0.11 | -0.67 |

| FRI Mean Item Score - Youth | 0.55 (0.17) | 0 to 1 | -025 | -0.46 |

| CESD Mean Item Score - Parent | 1.03 (0.66) | 0 to 3 | 0.41 | -0.75 |

| CSQ Mean Item Score - Parent | 1.92 (0.86) | 1 to 5 | -0.08 | -0.83 |

| Expectations/Prior Use Variables | ||||

| Tx Expectation Sum Score - Parent | 7.08 (1.08) | 2 to 8 | -0.94 | 0.07 |

| Tx Expectation Sum Score - Youth | 6.65 (1.31) | 2 to 8 | -0.86 | -0.00 |

| Treatment Characteristics | ||||

| Clinician Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 58% (n=32) | |||

| Other | 42% (n=23) | |||

| Clinician Gender | ||||

| Male | 24% (n=13) | |||

| Female | 76% (n=42) | |||

| Clinician Status | ||||

| Trainee | 58% (n=32) | |||

| Staff | 42% (n=23) | |||

| Clinician Years of Experience | 5.95 (5.17) | 1 to 34 | 3.49 | 16.45 |

| Number of Sessions Completedc | 14.08 (9.25) | 0 to 46 | 0.55 | 0.26 |

Note: CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; YSR = Youth Self-Report; VFI = Vanderbilt Functional Impairment Scale; FRI = Family Relationship Inventory; CESD = Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale; CSQ = Caregiver Strain Questionnaire; Tx = Treatment.

n=119 due to administrative error at participating clinics.

These categories are not mutually exclusive as clinicians could assign more than one diagnosis.

Number of sessions completed over the six-month period prior to follow-up assessment.

Table 1b.

Descriptives of Satisfaction Measures at Six-Month Follow-Up and Change Scores on Youth Clinical Functioning Variables (n=143)

| Variable | M (SD) | Range | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction Measures | ||||

| Satisfaction Mean Item Score - Parent | 3.19 (0.65) | 1 to 4 | -0.98 | 0.64 |

| Satisfaction Mean Item Score - Youth | 3.20 (0.50) | 1 to 4 | -0.78 | 0.21 |

| Change in Youth Clinical Functioning | ||||

| CBCL Total Change T-Score – Parenta | 3.08 (7.73) | -20 to 26 | 0.26 | 1.01 |

| YSR Total Change T-Score – Youtha | 4.65 (11.45) | -22 to 52 | 0.71 | 2.97 |

| VFI Mean Item Change Score - Parent | 0.40 (0.19) | -0.43 to 0.71 | 0.36 | 1.10 |

| VFI Mean Item Change Score - Youth | 0.02 (0.16) | -0.40 to 0.67 | 0.26 | 1.34 |

Note: CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; YSR = Youth Self-Report; VFI = Vanderbilt Functional Impairment Scale; for change scores, a higher score value represents a greater reduction in the score from baseline to six-month follow-up.

n=112 due to administrative error at participating clinics (24 cases missing baseline assessment; additional 7 cases missing six-month follow-up assessment).

Correlations between Satisfaction and Change in Clinical Outcomes

The coefficients presented in Table 2 represent zero-order correlations between satisfaction and change scores on clinical outcomes. The results indicate that youth satisfaction was significantly associated with reductions in parent-reported symptoms (CBCL) (r = .20) and that parent-reported satisfaction was significantly associated with youth-reported reductions in functional impairment (r = .29).

Table 2.

Zero-Order Correlations between Satisfaction and Change Scores on Youth Clinical Functioning Variables (n=143)

| Clinical Change Score | Satisfaction-Youth | Satisfaction-Parent |

|---|---|---|

| CBCL Total Change – Parenta | .20* | .14 |

| YSR Total Change – Youtha | -.09 | .08 |

| VFI Total Change – Parent | .18* | -.13 |

| VFI Total Change – Youth | .05 | .29** |

Note. Higher scores on the clinical change variables indicate greater reductions in symptoms or functional impairment. CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; YSR = Youth Self Report; VFI = Vanderbilt Functioning Index.

n=112 due to administrative error at participating clinics (24 cases missing baseline assessment; additional 7 cases missing six-month follow-up assessment).

p < .05,

p < .01.

Correlations between Satisfaction and Service Entry Characteristics

Table 3 presents zero-order correlation coefficients assessing the relationship between youth and parent satisfaction and a variety of service entry characteristics, grouped into the following categories: sociodemographic factors, child clinical characteristics, parent/family characteristics, and prior service experiences/current service expectations. The only statistically significant correlates of satisfaction for youths were youth race/ethnicity, with Caucasian youths reporting significantly higher rates of satisfaction than youths who were not Caucasian, and youth report on treatment expectations, with more positive expectations being significantly associated with higher satisfaction. The only statistically significant correlate of parent satisfaction was caregiver strain, whereby parents reporting lower levels of caregiver strain at baseline reported significantly higher rates of satisfaction.

Table 3.

Zero-Order Correlations between Satisfaction and Service Entry Characteristics (n=143).

| Predictor Variables | Satisfaction-Youth | Satisfaction-Parent |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||

| Youth Age | .13 | -.09 |

| Youth Gender (0=female; 1=male) | -.08 | .13 |

| Youth Ethnicity (0=Caucasian; 1=other) | -.21* | -.09 |

| Parent Gender (0=female; 1=male) | .13 | -.01 |

| Family Income | .01 | .03 |

| Child Clinical Characteristics | ||

| CBCL baseline Total T-Score – Parenta | .02 | -.13 |

| YSR baseline Total T-Score – Youtha | -.13 | -.01 |

| VFI baseline Mean Item Score – Parent | .05 | -.12 |

| VFI baseline Mean Item Score – Youthb | -.13 | .04 |

| Externalizing Diagnosis – Clinician | -.01 | .07 |

| Mood Diagnosis – Clinician | -.07 | -.11 |

| Anxiety Diagnosis – Clinician | .16 | .01 |

| Parent/Family Characteristics | ||

| Family Relationship – Parent | -.05 | .05 |

| Family Relationship – Youth | .11 | -.06 |

| Parental Depression – Parent | .02 | -.06 |

| Caregiver Strain – Parent | -.02 | -.20* |

| Treatment Expectations | ||

| Treatment Expectations – Parent | .07 | .07 |

| Treatment Expectations – Youth | .25** | .10 |

Note. CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; YSR = Youth Self Report; VFI = Vanderbilt Functioning Index.

n = 119 due to administrative error.

Square root transformation.

p < .05,

p < .01.

Relations between Satisfaction and Treatment/Therapist Characteristics

Table 4 presents zero-order correlation coefficients between satisfaction and treatment/therapist characteristics. Results indicate that youths who reported higher satisfaction had clinicians with significantly more years of experience. For parent report of satisfaction, the results indicate that parents who reported higher satisfaction had children who attended significantly more sessions.

Table 4.

Zero-Order Correlations between Satisfaction and Treatment/Therapist Characteristics (n=143).

| Treatment Characteristic | Satisfaction-Youth | Satisfaction-Parent |

|---|---|---|

| Clinician Ethnicity (0=Caucasian; 1=other) | -.08 | -.04 |

| Clinician Gender (0=female; 1=male) | .03 | .10 |

| Clinician Status (0 = Trainee; 1 = Staff) | .13 | .12 |

| Clinician Years of Experiencea | .17** | .07 |

| Number of Sessions | .13 | .18* |

Natural log transformation.

p < .05,

p < .01.

Predictive Power of Significant Correlates of Satisfaction

Tables 5a and 5b present the overall predictive power of the significant child clinical change variables, service entry characteristics, and treatment/therapist characteristics to explain variance in parent and youth reports of satisfaction. For each reporter of satisfaction, the statistically significant predictors within Tables 2 through 4 were included in a regression model predicting the corresponding reporter of satisfaction.

Table 5a.

Youth Satisfaction Regressed on Robust Predictors.

| Predictor | β | p value for β | R2 Change | p value for R2 Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step #1. Baseline Variables | ||||

| Youth Ethnicitya | -.271 | .004 | .111 | ..005 |

| Treatment Expectations - Youth | .209 | .025 | ||

| Clinician Years of Experienceb | .154 | .096 | ||

| Step #2. Clinical Change Scores | ||||

| CBCL Change – Parent | .149 | .139 | .043 | .060 |

| VFI Change – Parent | .095 | .354 |

Note. n = 112; Model R2 = .154; CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; VFI = Vanderbilt Functioning Index.

Ethnicity is coded as 0 = Caucasian; 1 = other.

Natural log transformation.

Table 5b.

Parent Satisfaction Regressed on Robust Predictors.

| Predictor | β | p value for β | R2 Change | p value for R2 Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step #1. Baseline Variables | ||||

| Caregiver Strain – Parent | -.214 | .010 | .079 | .003 |

| Number of Sessions | .201 | .015 | ||

| Step #2. Clinical Change Scores | ||||

| VFI Change – Youth | .349 | .000 | .114 | .000 |

Note. n = 143; Model R2 = .193. VFI = Vanderbilt Functioning Index.

For youth report of satisfaction, the overall model R2 = .154, indicating that 15.4% of the total variance in youth report of satisfaction was explained by the significant service entry, treatment/therapist characteristics, and clinical change variables. For parent report of satisfaction, the overall model R2 = .193, indicating that 19.3% of the total variance in parent report of satisfaction was explained by the significant service entry, treatment/therapist characteristics, and clinical change variables. For youth report of satisfaction, only youth ethnicity and youth report of treatment expectations retained their significant association with satisfaction in the regression analysis, while for parent report of satisfaction all of the predictor variables retained their significance in the regression analysis. The magnitudes of associations were relatively low with most effect sizes under .20.

Discussion

The results suggest that the construct of client satisfaction with youth psychotherapy is complex. Consistent with most existing literature, parents and youths reported generally positive satisfaction, but youth and parent satisfaction were only minimally related to each other. The correlation found in this study between youth and parent satisfaction (r = .26) is similar to the correlation reported by Godley and colleagues (1998) (r = .16 for youth and parent satisfaction with individual therapy). In addition, there are few significant determinants of either informant's report of satisfaction.

The primary aim of this study was to examine the extent to which parent and youth satisfaction with out-patient mental health care could be accounted for by a wide variety of potential determinants, including prospectively measured change in patient clinical outcomes, factors pre-determined at service entry, and characteristics of the treatment itself. The results generally suggest that satisfaction is only minimally (but statistically significantly) associated with variables in all three categories. Consequently, the majority of the variance in satisfaction remained unaccounted for even after testing for many different potential correlates across the multiple categories of variables, reinforcing the complexity of the satisfaction construct. These negative findings are important given the fact that satisfaction is such commonly used indicator of the quality of services.

Consistent with some of the existing literature, we found a significant correlation between change in the patient clinical outcome of functional impairment and youth and parent satisfaction (Fontana & Rosenheck, 2001; Fontana et al., 2003; Garland et al., 2003), and this relationship was replicated for youth satisfaction in regression analyses accounting for potential overlapping variance with other constructs. In addition, we found a bivariate relationship between parent-reported overall change in symptom severity and youth (but not parent) satisfaction but this relationship did not remain significant in the regression analysis. The fact that there was a significant cross-informant effect whereby change in youth report of functional impairment was associated with parent-reported satisfaction is particularly noteworthy because some have argued that any relationship found between these constructs (i.e., satisfaction and clinical change) is due to shared informant variance as opposed to actual shared variance between the constructs (Lambert et al., 1998). However, it is also important to emphasize that the magnitude of the relationship we found was very small; only 4.3% of the variance in youth satisfaction and 11.4% of the variance in parent satisfaction was accounted for by the significant clinical change variables (see Table 5). Thus, we conclude that youth and parent satisfaction with care are significantly, though minimally, associated with reductions in youth functional impairment.

This study did not strongly support previous speculation by our research group that client satisfaction may be largely pre-determined at service entry by clinical characteristics and/or treatment expectations (Garland et al., 2000a; Garland et al., 2003). We tested for many different potential predictors of satisfaction, including numerous demographic variables, child clinical variables, parent/family characteristics, and treatment expectations (see Table 3). Only youth race/ethnicity (Caucasian youths reported higher satisfaction than minority youths) and treatment expectations (more positive expectations associated with higher satisfaction six months later) were associated with youth satisfaction. Only caregiver strain was associated with parent satisfaction (higher strain at entry was associated with lower satisfaction). The lack of demographic predictors of parent satisfaction with children's mental health services is consistent with several other studies (Martin et al., 2003). However, several studies have reported that more severe patient symptomatology is associated with client satisfaction in an inverse direction (Garland et al., 2000a; Godley et al., 1998), and we did not find these effects. In particular for parent-reported symptomatology, the data did not even show a trend in this direction, thus discounting lack of power as an explanation. Our sample did exhibit relatively high symptom severity on average (mean CBCL total behavior problem T score of 67.2, SD = 9.6), and it is possible that other studies have included patients with a wider range of symptom severity with youths with low severity reporting particularly high satisfaction.

Although the study did not include detailed measurement of psychotherapeutic processes, we were able to test the relationship between several therapist/treatment characteristics and satisfaction and, again, found few significant effects. Youth satisfaction was positively associated with the therapist's years of experience. Parent satisfaction was positively associated with the number of treatment sessions. Several other studies have reported a positive relationship between duration of treatment and satisfaction (Brannan et al., 1996; Godley et al., 1998; Lebow, 1982), but the causal direction of the relationship is not known (i.e., satisfied patients may attend more sessions and/or increased duration of treatment may improve satisfaction. We are not aware of studies reporting an effect of therapist experience on satisfaction. Again, all of these effects are of modest magnitude (i.e., largest correlation coefficient is .18).

Strengths and Limitations

There are many methodological strengths of this study, including use of well-established measures of client satisfaction and patient clinical outcomes and parent/family characteristics, a prospective design, and a diverse sample recruited from "real world" community-based clinics. Our measures of satisfaction have strong psychometric characteristics and sufficient variation in response, but are also very brief and thus feasible to administer in "real world" clinical settings, thus they are likely similar to measures used by public and private organizations. The sample is generally demographically and clinically representative of all youths receiving publicly-funded services in a large county system of care. The sample size has adequate power to address the study aims, but is not large enough to test the predictive power of all variables together. Although the sample is relatively ethnically diverse, it is too small to support analyses of different groups, requiring a less desirable strategy of grouping all ethnic minority categories together to compare to Caucasians. In addition, although the potential determinants of satisfaction included in the study encompassed a broad range of factors, there may be some important variables that were not assessed, including, most importantly, characteristics of the psychotherapy itself and richer data about provider-patient "match" on demographics, attitudinal/expectation variables, cognitive explanatory models of therapy, and therapeutic alliance.

Implications

Given that use of client satisfaction data has become standard practice for many, if not most, behavioral health organizations and private practitioners (Pekarik & Guidry, 1999), it is essential to critically examine the construct of satisfaction and its determinants. There is significant controversy over the extent to which satisfaction is an indicator of quality of care (Edlund et al., 2003; Seligman, 1996) and whether it should be labeled as an outcome of care as opposed to an indicator of treatment process (Pekarik & Guidry, 1999). Measurement of satisfaction is often fraught with methodological challenges (e.g., skewed data, lack of representative sample), but is far more feasible and more easily interpreted than repeated measurement of multiple informants' perspectives on clinical outcomes in practice. While client satisfaction may have important implications for patient engagement in treatment, this study, as well as others, reinforces concern that satisfaction should not be used to evaluate the effectiveness of care in achieving clinical outcome change for patients and families (Edlund et al., 2003; Lambert et al. 1998; Pekarik & Guidry, 1999).

This study revealed more about what does not determine client satisfaction than what does, supporting the need for more thorough investigation of this commonly assessed construct. Theoretically and empirically informed models of client satisfaction with mental health care need to be developed to guide interpretation of the construct and target new areas of research. Such models will incorporate theoretical work from other disciplines such as cognitive psychology, examining attitude formation and change. Like this study, most satisfaction research has been pragmatic and atheoretical, so more interdisciplinary work is needed. Future study should examine variables not assessed in this study or existing research. For example, satisfaction may be driven by patients' personality characteristics or cognitive styles, such as optimism, locus of control, or general conformity/social desirability. Satisfaction may also be determined by experiences in care not assessed in this study, ranging from "customer relations" type variables (e.g., courtesy and timeliness of telephone response, physical environment of the office/agency, convenience of scheduling, transportation, etc), to more complex, dynamic issues relating to the interpersonal interactions with the therapist. Satisfaction may also be driven by the fit between the patients'/patients' family's and the therapists' expectations or cognitive explanatory models for mental illness and treatment (Kleinman, 1978; Sue & Zane, 1987; Yeh et al., 2005). Client satisfaction is of paramount importance in the "real world" of practice and satisfaction data may drive fiscal and policy decision making. This somewhat elusive construct deserves more systematic study.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: Lauren Brookman-Frazee for her thoughtful comments on an earlier draft of this article, Scott Roesch for his statistical consultation, and Lindsay Lugo for her assistance in the preparation of this article. The authors would also like to thank the clinicians and families for their participation. This study was supported by grants K01-MH-01544 and R01-MH-66070 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the CBCL/4-18 and Profile. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; Burlington: 1991a. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the YSR/11-18 and Profile. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; Burlington: 1991b. [Google Scholar]

- Baker MJ, Miller B, Ganger W, Wilhite-Grow D, Mueggenborg MG, Zhang J. Children's Mental Health Services Fourth Annual System of Care Report. County of San Diego Health & Human Services Agency; San Diego, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L. Are you satisfied with satisfaction? (editorial) Mental Health Services Research. 2000;2:125. [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L, Lambert EW, Karver M, Andrade AR. Two low-cost measures of child and adolescent functioning for services research. Evaluation & Program Planning. 1998;21:263–275. [Google Scholar]

- Bilbrey J, Bilbrey P. Judging, trusting, and utilizing outcomes data: A survey of behavioral health care payers. Behavioral Health Care Tomorrow. 1995 July/August;:62–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxmeyer CL. Parent and family outcomes of community-based mental health treatment for adolescents. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences & Engineering. 2004;65(4B):2100. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley EJ, Clark BS. Patients' characteristics and consumer satisfaction on an inpatient child psychiatric unit. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;38:175–180. doi: 10.1177/070674379303800304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannan AM, Sonnichsen SE, Heflinger CA. Measuring satisfaction with children's mental health services: Validity and reliability of the Satisfaction Scales. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1996;19:131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Brannan AM, Heflinger CA, Bickman L. The Caregiver Strain Questionnaire: Measuring the impact on the family of living with a child with serious emotional disturbance. Journal of Emotional & Behavioral Disorders. 1997;5:212–222. [Google Scholar]

- Edlund MJ, Young AS, Kung FY, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. Does satisfaction reflect the technical quality of mental health care? Health Services Research. 2003;38:631–645. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana A, Ford JD, Rosenheck R. A multivariate model of patients' satisfaction with treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:93–106. doi: 10.1023/A:1022071613873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana A, Rosenheck R. A model of patients' satisfaction with treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Administration and Policy in Mental Healt. 2001;h:28–475. doi: 10.1023/a:1012270625680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Aarons G, Saltzman M, Kruse M. Correlates of adolescents' satisfaction with mental health services. Mental Health Services Research. 2000a;2:127–139. doi: 10.1023/a:1010137725958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Saltzman M, Aarons G. Adolescents' satisfaction with mental health services: Development of a multi-dimensional scale. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2000b;23:165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Aarons GA, Hawley K, Hough RL. Relationship of youth satisfaction with services and changes in symptoms and functioning. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:1544–1546. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.11.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley SH, Fielder EM, Funk RR. Consumer satisfaction of parents and their children with child/adolescent mental health services. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1998;21:31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Heflinger CA, Simpkins CG, Scholle SH, Kelleher KJ. Parent/Caregiver Satisfaction with their Child's Medicaid Plan and Behavioral Health Providers. Mental Health Services Research. 2004;6:23–32. doi: 10.1023/b:mhsr.0000011254.95227.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge RD, Andres DA, Faulkner PA, et al. The family relationship index: validity data. Journal of Clinical Psycholog. 1989;y:45–897. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198911)45:6<897::aid-jclp2270450611>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH. The quality of social support: Measures of family and work relationships. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1983;22:157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan S, Busner J, Chibnall J, et al. Consumer satisfaction at a child and adolescent state psychiatric hospital. Psychiatric Service. 2001;s:52–202. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mroczek DK. Measuring the effects of medical interventions. Medical Care. 1995;33:AS109–AS119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Clinical relevance of anthropological and cross-cultural research: Concepts and strategies. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1978;135:427–431. doi: 10.1176/ajp.135.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert W, Salzer MS, Bickman L. Clinical outcome, consumer satisfaction, and ad hoc ratings of improvement in children's mental health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:270–279. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, Nguyen TD. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1979;2:139–150. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebow J. Consumer satisfaction with mental health treatment. Psychological Bulletin. 1982;91:244–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Q, Sukumar B. Relationship among service use, outcomes, and caregiver satisfaction; 17th Annual Conference Proceedings: A System of Care for Children's Mental Health: Expanding the Research Base..2005. pp. 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Loff CD, Trigg JL, Cassels C. An evaluation of consumer satisfaction in a child psychiatric service: viewpoints of patients and parents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57:132–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JS, Petr CG, Kappy SA. Consumer satisfaction with children's mental health services. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2003;20:211–226. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe KM, Yeh M, Lau A, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in caregiver strain and perceived social support among parents of youth with emotional and behavior problems. Mental Health Services Research. 2003;5:137–147. doi: 10.1023/a:1024439317884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekarik G, Guidry LL. Relationship of satisfaction to symptom change, follow-up adjustment, and clinical significance in private practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1999;30:474–478. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins JM, Taylor JL, Rost KM, Burns BJ, Phillips SD, Burnam MA, Smith GR. Measuring outcomes of care for adolescents with emotional and behavioral problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:315–324. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200103000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen LD, Heckman MA, Carro MG, Burchard JD. Satisfaction, involvement, and unconditional care: The perceptions of children and adolescents receiving wraparound services. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1994;3:55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt A, Wyman N, Kingdon D, Ichinose C. Managing what you measure: Creating outcome-driven systems of care for youth with serious emotional disturbances. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 1998;25:177–193. doi: 10.1007/BF02287479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzer M. The outcomes measurement movement and mental health services research: A review of three books. Mental Health Services Research. 1999;1:59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP. A creditable beginning. American Psychologist. 1996;51:1086–1088. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro JP, Welker CJ, Jacobson BJ. The Youth Client Satisfaction Questionnaire: Development, construct validation, and factor structure. Journal of Child Clinical Psychology. 1997;26:87–98. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2601_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Zane N. The role of culture and cultural techniques in psychotherapy: A critique and reformulation. American Psychologist. 1987;42:37–45. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.42.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Doss AJ, Hawley KM. Youth psychotherapy outcome research: A review and critique of the evidence base. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:337–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RH, Zimmerman DW. Are simple gain scores obsolete? Applied Psychological Measurement. 1996;20:59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh M, McCabe K, Hough RL, Lau A, Fakhry F, Garland A. Why bother with beliefs?: Examining relationships between race/ethnicity, parental beliefs about causes of child problems, and mental health service use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:800–807. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SC, Nicholson J, Davis M. An overview of issues in research on consumer satisfaction with child and adolescent mental health services. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1995;4:219–238. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman DW, Williams RH. Reliabiity of gain scores under realistic assumptions about properties of pre-test and post-test scores. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 1998;51:343–351. [Google Scholar]