Abstract

Background

Following infection with viruses, bacteria or protozoan parasites, naïve antigen-specific CD8+ T cells undergo a process of differentiation and proliferation to generate effector cells. Recent evidences suggest that the timing of generation of specific effector CD8+ T cells varies widely according to different pathogens. We hypothesized that the timing of increase in the pathogen load could be a critical parameter governing this process.

Methodology/Principal Findings

Using increasing doses of the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi to infect C57BL/6 mice, we observed a significant acceleration in the timing of parasitemia without an increase in mouse susceptibility. In contrast, in CD8 deficient mice, we observed an inverse relationship between the parasite inoculum and the timing of death. These results suggest that in normal mice CD8+ T cells became protective earlier, following the accelerated development of parasitemia. The evaluation of specific cytotoxic responses in vivo to three distinct epitopes revealed that increasing the parasite inoculum hastened the expansion of specific CD8+ cytotoxic T cells following infection. The differentiation and expansion of T. cruzi-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T cells is in fact dependent on parasite multiplication, as radiation-attenuated parasites were unable to activate these cells. We also observed that, in contrast to most pathogens, the activation process of T. cruzi-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T cells was dependent on MHC class II restricted CD4+ T cells.

Conclusions/Significance

Our results are compatible with our initial hypothesis that the timing of increase in the pathogen load can be a critical parameter governing the kinetics of CD4+ T cell-dependent expansion of pathogen-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T cells.

Introduction

MHC class Ia-restricted CD8+ T cells are important mediators of the adaptive immune response against infections caused by intracellular microorganisms. Following infection with certain viruses, bacterias or parasites, naïve antigen-specific CD8+ T cells go through a process of fast differentiation and proliferation, generating effector cytotoxic cells (expansion phase). These effector cells circulate between lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues to restrain the multiplication of the infectious pathogen. Following pathogen elimination, the number of specific effector CD8+ T cells is drastically reduced (contraction phase) and the establishment of a long-lived population of memory T cells responsible for perpetuating immunity against re-infection takes place. This kinetics of effector CD8+ T cell expansion, contraction and establishment of a memory population has been fairly well reproduced and it is being thoroughly studied in a number of experimental models, including virus, bacterias and protozoan parasites (reviewed in ref. 1–3).

Using these experimental models, it was possible to establish that specific CD8+ T cells differentiate and proliferate very quickly reaching a peak between days 4 and 8 after immunization with either lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), influenza virus, vaccinia virus, Listeria monocytogenes or Plasmodium yoelli [4]–[9]. Recent studies in mice infected with Toxoplasma gondii, Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG), Trypanosoma cruzi and Salmonella typhimurium described significantly different kinetics of differentiation and proliferation of specific CD8+ T cells. In the case of T. gondii, CD8+ T cells specific for a transgenic epitope became detectable only 10 days after challenge, and the maximum number of epitope-specific T cells peaked at day 23 [10]. Similarly, in mice injected with recombinant S. typhimurium or BCG the peak response to the transgenic epitope was day 21st or 30th following challenge, respectively [11], [12].

We recently described the kinetics of parasite-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T cell responses following mouse infection with the human protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi [13]. An interesting finding was that the initial inoculum of T. cruzi did not drive the differentiation and proliferation of effector CD8+ T cells. The expansion phase of specific splenic CD8+ T cells occurred after in vivo multiplication of parasites, between days 9 and 15 after i.p. challenge of C57BL/6 mice with 104 parasites of the Y strain. More recently, Martin et al., (2006) confirmed and extended our results in studies using different T. cruzi strains, which revealed that the peak of parasite epitope-specific CD8+ T cells could vary from 14 to 24 days post-infection [14].

The results obtained during T. gondii, BCG, S. typhimurium or T. cruzi infections sharply differed from the observations made in mice infected with LCMV, vaccinia, influenza, L. monocytogenes or P. yoelli and raised questions on the possible mechanisms controlling the kinetics of differentiation and proliferation following infection with different pathogens.

One mechanism that could influence the kinetics of specific CD8+ T cells differentiation and proliferation is the amount of antigen and parasite-derived adjuvant both of which accumulate during the infection. Immediately after the initial infectious inoculum, the amount of antigen and parasite adjuvant available for CD8+ T-cell priming may be limited, however both will increase after pathogen multiplication, and then may reach a certain threshold necessary to promote the maturation of antigen presenting cells (APC) - in the case of the adjuvant molecule - and trigger the activation of naïve CD8+ T cells, in the case of the antigen. If this hypothesis is correct, the timing of increase of pathogen adjuvant/antigen would be a key parameter governing the process of CD8+ T cell differentiation and expansion.

The aim of the present study was to determine whether modulation of the parasite load within a certain period of time can in fact alter the activation of effector/protective CD8+ T cells. For this purpose, we used an experimental model where C57BL/6 mice were challenged with different doses of parasite of the Y strain of Trypanosoma cruzi. This strategy allowed us to modulate the timing of increase in the parasite load and determine the effect it may have on the in vivo differentiation and proliferation of effector/protective CD8+ T cells. Using this experimental model, we were able to lend support to the hypothesis that the timing of accumulation of the parasite load can be a key factor influencing the differentiation and proliferation of CD4+ T cell-dependent specific CD8+ cytotoxic T cells following infection with a human pathogen.

Methods

Mice and parasites

Female 8 to 10-week-old wild type (WT) C57BL/6, CD8α deficient C57BL/6 (CD8 KO), MHC-II deficient C57BL/6 (MHC-II KO), CD4 deficient C57BL/6 (CD4 KO), p40 deficient C57BL/6 (IL-12 KO), wild type 129 and 129 deficient for the IFN-I receptor (IFN-I receptor KO) were obtained from University of São Paulo. Perforin deficient C57BL/6 (Perforin KO) mice were bred on our own facility.

Parasites of the Y strain of T. cruzi were used in this study [13]. Bloodstream trypomastigotes were obtained from the plasma of A/Sn mice infected 7 days earlier. The concentration of parasites was adjusted and each mouse was inoculated intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 0.2 mL containing the indicated amount of trypomastigotes. Parasite development was monitored by counting the number of bloodstream trypomastigotes in 5 µl of fresh blood collected from the tail vein [13]. When the parasitemia was above 105 trypomastigotes per mL, blood samples were diluted and the number of parasites estimated with the aid of a hemacytometer. Radiation-attenuated parasites were obtained by exposing them to gamma-irradiation (100 krads).

Immunological assays

For the in vivo cytotoxicity assays, C57BL/6 splenocytes were divided into two populations and labeled with the fluorogenic dye carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl diester (CFSE Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon, USA) at a final concentration of 5 µM (CFSEhigh) or 0.5 µM (CFSElow). CFSEhigh cells were pulsed for 40 min at 37°C with 1 µM of the H-2Kb ASP-2 peptide (VNHRFTLV), or TsKb-18 (ANYKFTLV) or TsKb-20 (ANYDFTLV). CFSElow cells remained unpulsed. Subsequently, CFSEhigh cells were washed and mixed with equal numbers of CFSElow cells before injecting intravenously (i.v.) 15 to 20×106 total cells per mouse. Recipient animals were mice that had been infected or not with T. cruzi. Spleen cells of recipient mice were collected 20 h after transfer, fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde and analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), using a Facscalibur Cytometer (BD, Mountain View, CA). The percentage of specific lysis was determined using the formula:

| 1 |

The ELISPOT assay for enumeration of Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) producing cells was performed essentially as described earlier [15].

Statistical analysis

The values of were compared by One-Way Anova followed by Tukey HSD tests available at the site http://faculty.vassar.edu/lowry/VassarStats.html. The LogRank test was used to compare the mouse survival rate after challenge with T. cruzi. The differences were considered significant when the P value was <0.05.

Results

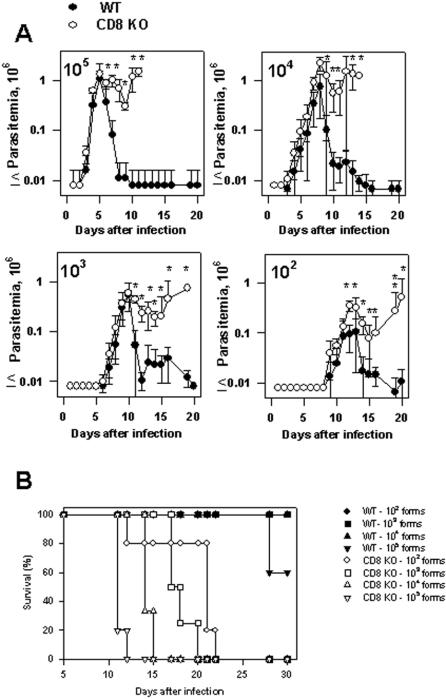

In initial studies we investigated the development of T. cruzi parasitemia in wild type C57BL/6 mice challenged i.p. with different doses of trypomastigotes (102, 103, 104 or 105 parasites per mouse). As shown in figure 1, infection with 102 parasites generated a parasitemia that could be first detected at day 8 and peaked at day 11 post challenge. Doses of 103, 104 or 105 parasites hastened the initial detection of parasitemia to days 5, 4 and 3, respectively. The peak parasitemia in mice receiving the highest parasite doses was also earlier, at days 9, 8 or 5 respectively. The magnitude of the peak parasitemias between the different mice groups was not significantly different when comparing groups of mice infected with 105 or 104. Similarly, no difference was found when comparing groups of mice infected with 103 or 102. Mice infected with 103 parasites presented a peak parasitemia lower (P<0.05) than the mouse group infected with 104 but not with 105 parasites. In repeated experiments, mice infected with 102 parasites presented a peak parasitemia lower than mouse groups infected with 104 or 105 (P<0.01 in both cases).

Figure 1. Trypomastigote-induced parasitemia in C57BL/6 mice challenged with different doses of trypomastigotes of T. cruzi.

C57BL/6 mice were infected i.p. with 102,103, 104 or 105 bloodstream trypomastigotes of the Y strain of T. cruzi. Parasitemia was followed daily from days 0 to 14 after challenge. The results represent the mean of 5–6 mice±SD. At the peak of infection, the parasitemia of mice infected with each different dose was compared by One-way Anova and Tukey HSD tests. The results of the comparisons were as follows: i) 102×103, Non-Significant (NS); ii) 102×104, P<0.01; iii) 102×105, P<0.01; iv) 103×104, P<0.05; v) 103×105, NS; vi) 104×105, NS. Results are representative of two independent experiments.

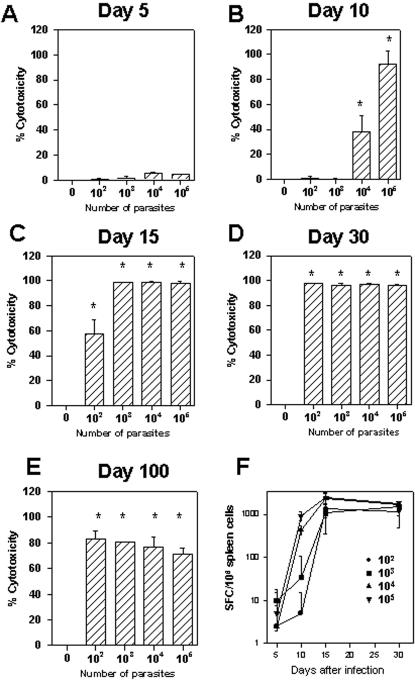

In view of these results, we concluded that there is an inverse relationship between parasite inoculum and the timing of the development of T. cruzi parasitemia, a feature that had not been described. In addition, we observed that the peak parasitemia did not differ significantly among groups of mice injected with 103, 104, or 105 parasites. Mice infected with 102 parasites consistently presented lower peak parasitemia than animals challenged with much higher parasite doses (104 or 105 parasites per mouse). In spite of the fact that the parasitemia reached the peak earlier when the parasite inoculum was increased, these mice were capable of controlling the infection and survived the challenge. Because in this mouse model of infection CD8+ T cells are critical for survival [13], the fact that animals injected with increasing parasite inoculum survived infection suggested that they were able to develop protective immunity in spite of increasing the infective dose. To determine whether protective immunity dependent on CD8+ T cells could indeed be developed in these animals, we compared the parasitemia and mortality of wild type and CD8 KO mice following infection with different doses of parasites. As shown in figure 2A, when comparing infected wild type and CD8 KO mice, the ascendant part of the curve of parasitemia was not significantly different. These results indicated that CD8+ T cells were not important for parasite control during that period regardless of the parasite dose used for challenge. After the day of the peak parasitemia, wild type mice rapidly controlled the number of parasites in the blood. In sharp contrast, CD8 KO mice were unable to control the parasitemia, became ill and eventually died.

Figure 2. Infection in WT C57BL/6 or CD8 KO mice challenged with different doses of T. cruzi.

Groups of WT C57BL/6 or CD8 KO were infected i.p. with 102,103, 104 or 105 bloodstream trypomastigotes of the Y strain of T. cruzi. (A) Course of infection, estimated by the number of trypomastigotes per mL of blood. Results represent the mean values of 4–5 mice±SD. The parasitemias of WT C57BL/6 or CD8 KO mice were compared by One-way Anova. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences (P<0.05). (B) Kaplan-Meier curves for survival of WT C57BL/6 or CD8 KO infected mice with different doses of parasites. Statistical analyses were performed using LogRank test comparing the different mouse groups. Initially, we compared groups of WT C57BL/6 infected with different doses. The results of the comparison showed no statistically significant differences among them. Subsequently, we compared WT C57BL/6 or CD8 KO infected with each different dose of parasites. The results of the comparison showed statistically significant differences in between C56BL/6 or CD8 KO challenged with each parasite dose (P<0.0001, in all cases). Finally, statistical analyses were performed comparing the groups of CD8 KO infected with different doses. The results of the comparison were as follows: i) CD8 KO 102×CD8 KO 103 (P = 0.0025); ii) CD8 KO 102×CD8 KO 104 (P = 0.0046); iii) CD8 KO 102×CD8 KO 105 (P = 0.0016); iv) CD8 KO 103×CD8 KO 104 (P = 0.01); v) CD8 KO 103×CD8 KO 105 (P = 0.0035); vi) CD8 KO 104×CD8 KO 105 (P = 0.0082).

When we compared the timing of death of each group of CD8 KO mice, we observed an inverse relationship between the size of parasite inoculum and the timing of death. Statistical analysis revealed a significant difference among the groups of infected CD8 KO mice (P≤0.01 in all cases, Fig. 2B). As wild type mice survived, these results clearly confirmed the importance of CD8+ T cells as a protective mechanism in mice infected with different doses of parasite. These results also suggest that the activation of protective CD8+ T cells in wild type C57BL/6 mice takes place earlier as the parasite inoculum is increased.

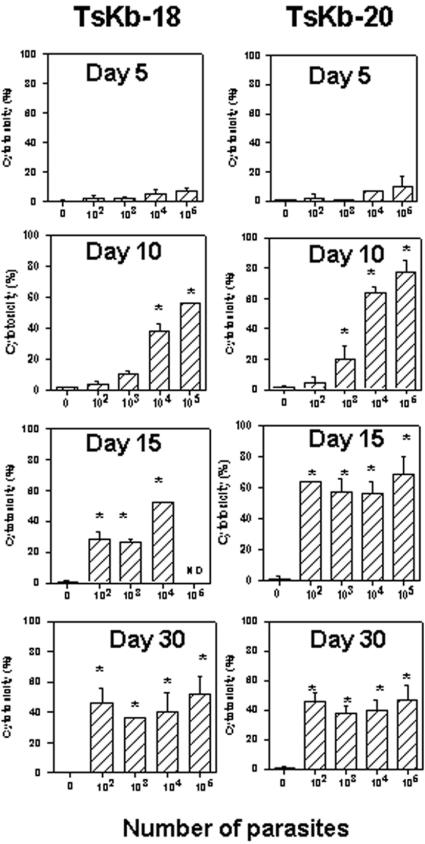

To determine whether there was an inverse relationship between the parasite inoculum used for infection and the timing of expansion of specific CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, we characterized the kinetics of effector CD8+ T cell development. For this purpose we used a functional cytotoxic assay which measures the in vivo elimination of target cells coated with peptide VNHRFTLV [13]. The phenotype of effector cells mediating peptide-specific in vivo cytotoxicity was established earlier as being CD8+ T cells [13]. As shown in Fig. 3A, at day 5 post-infection, none of the mouse groups presented peptide-specific cytotoxicity. At day 10 day post-infection, we observed a direct correlation between the size of parasite inoculum and intensity of the in vivo cytotoxicity (Fig. 3B). By day 15th, groups of mice infected with 103, 104 or 105 parasites had reached their maximum cytotoxicity (close to 100% specific lysis). In contrast animals infected with 102 parasites still displayed only ∼50% cytotoxic activity (Fig. 3C). By day 30th post-infection, the in vivo cytotoxicity reached frequencies close to 100% in all mouse groups (Fig. 3D). The in vivo cytotoxicity continued at a high level in all infected groups until tested 100 days after challenge (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3. Kinetics of specific CD8+ T-cell mediated immune responses following challenge with T. cruzi.

Groups of C57BL/6 mice were challenged or not i.p. with 102,103, 104 or 105 bloodstream trypomastigotes of the Y strain of T. cruzi. Panels A to E - At the indicated days, the in vivo cytotoxic activity against target cells coated with peptide VNHRFTLV was determined as described in the Methods Section. The results represent the mean of 4 mice±SD per group. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences when we compared T. cruzi challenged with control mice (P<0.05). Panel F- At the indicated days, IFN-γ producing spleen cells specific to the peptide VNHRFTLV were estimated by the ELISPOT assay. The results represent the mean number of peptide-specific spot forming cells (SFC) per 106 splenocytes±SD (n = 4). Results are representative of two or more independent experiments.

IFN-γ ELISPOT assays confirmed that at day 5 post-infection few peptide-specific T cells were detected in mice infected with increasing doses of T. cruzi. A direct correlation between the size of parasite inoculum and the number of peptide-specific cells was clearly evident by day 10 post-infection. By day 15th or 30th, in all mice groups we detected a high frequency of IFN-γ producing specific T cells (Fig. 3F).

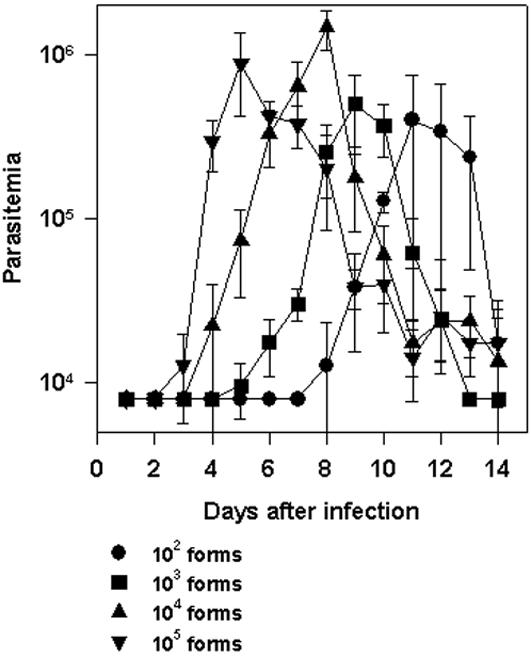

To evaluate whether the results described above could also be extended to other parasite epitopes, we evaluated the kinetics of the in vivo cytotoxicity specific for two other sub-dominant epitopes (TsKb-18 and TsKb-20, ref. 14). We found that the kinetics of cytotoxicity for both sub-dominant epitopes was also dependent on the dose of parasites used for the challenge (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Kinetics of CD8+ T-cell mediated immune responses specific for sub-dominant epitopes in C57BL/6 mice.

Groups of C57BL/6 mice were challenged or not i.p. with 102,103, 104 or 105 bloodstream trypomastigotes of the Y strain of T. cruzi. At the indicated days, the in vivo cytotoxic activity against target cells coated with peptide TsKb-18 or TsKb-20 was determined as described in the Methods Section. The results represent the mean of 4 mice±SD per group. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences when we compared T. cruzi challenged with control mice (P<0.05). ND = Not done. Results are representative of two or more independent experiments.

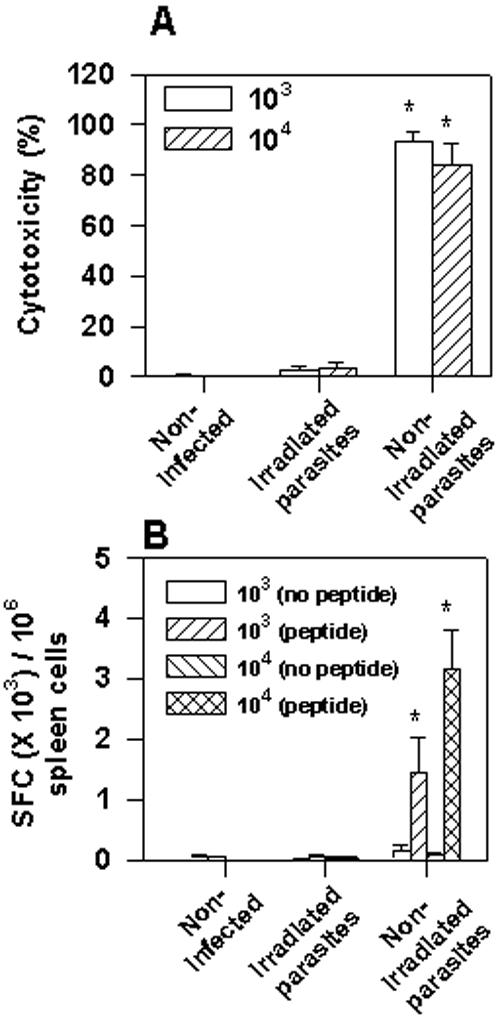

The results presented above established an inverse relationship between the parasite inoculum and the timing of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells differentiation and proliferation. However, it was not clear whether this event was in fact dependent on parasite multiplication or depended solely on dose of parasite used for challenge. To address this question, we challenged mice with irradiated or non-irradiated parasites. Irradiated parasites maintain their viability as assessed by their motility and capacity to infect host cells in vitro. However, they are unable to multiply (in vitro or in vivo) and establish an infection as determined by absence of parasitemia. Mice challenged with 103 or 104 irradiated parasites did not develop detectable in vivo cytotoxic activity or IFN-γ producing cells (Fig. 5A and 5B, respectively). In contrast, animals challenged with 103 or 104 non-irradiated parasites developed strong cytotoxic responses and peptide-specific IFN-γ producing cells (Fig. 5A and 5B, respectively). This result suggested that parasite replication was indeed an important factor to promote differentiation and proliferation of cytotoxic T cells.

Figure 5. Specific cytotoxicity in C57BL/6 mice challenged with irradiated or non-irradiated trypomastigotes of T. cruzi.

Groups of C57BL/6 mice were challenged or not i.p. with 103 or 104 irradiated or non-irradiated bloodstream trypomastigotes of the Y strain of T. cruzi. A) Fifteen days after challenge, the in vivo cytotoxic activity against target cells coated with peptide VNHRFTLV was determined. The results represent the mean of 4 mice±SD per group. B) Fifteen days after challenge, IFN-γ producing spleen cells specific to the peptide VNHRFTLV were estimated by the ELISPOT assay. The results represent the mean number of SFC per 106 splenocytes±SD (n = 4). Asterisks denote statistically significant differences (P<0.05) when we compared mice challenged with irradiated or non-irradiated trypomastigotes of T. cruzi. Results are representative of two independent experiments.

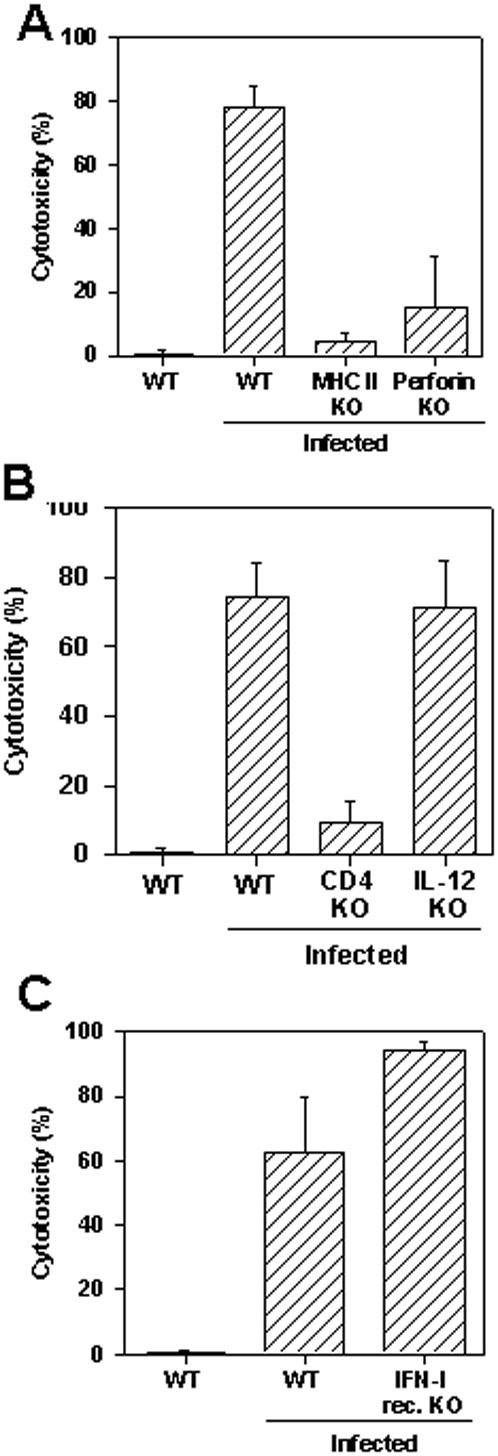

Because certain genetically deficient mice are highly susceptible to T. cruzi infection, and die before specific CD8+ T cells could be detected, it is difficult to study the importance that certain cells/molecules may have on proliferation and development of effector functions of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells following T. cruzi infection. However, the fast development of cytotoxic T cells observed in mice infected with large doses of T. cruzi (105 parasites per mouse), allowed us to study some of the molecules of the immune system that could play an important role in the development of protective CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. Using this strategy, we were able to study whether genetically deficient mice lacking MHC-II, CD4, IL-12, perforin or IFN-I receptor were capable of developing specific CD8+ cytotoxic T cell responses. We found that MHC-II or CD4 KO mice developed negligible levels of specific cytotoxicity in vivo (Fig. 6A and B, respectively). In contrast, IL-12 KO or IFN-I receptor KO mice developed normal levels of specific cytotoxicity in vivo (Fig. 6A and 6C, respectively). Cytotoxicity mediated by CD8+ T cell responses in Perforin KO mice were significantly reduced (∼75%) compared to control wild type animals. The results of these studies clearly indicate that MHC-II and CD4 are key molecules for the induction of an effective cytotoxic CD8+ T cell response following T. cruzi infection.

Figure 6. Specific cytotoxicity in WT or genetically deficient mice challenged with T. cruzi.

Groups of WT C57BL/6 (n = 4), WT 129 mice (n = 4), MHC-II KO (n = 4), perforin KO (n = 8), CD4 KO (n = 4), IL-12 KO (n = 4), and IFN-I receptor KO (n = 4) were challenged or not i.p. with 105 bloodstream trypomastigotes of the Y strain of T. cruzi. Ten days after challenge, the in vivo cytotoxic activity against target cells coated with peptide VNHRFTLV was determined. The results represent the mean of the above indicated number of mice±SD per group. The in vivo cytotoxicity was compared by One-way Anova and Tukey HSD tests. The results of the comparisons were as follows: i) WT C57BL/6×MHC-II KO (P<0.01); ii) WT C57BL/6×Perforin KO (P<0.01); iii) WT C57BL/6×CD4 KO (P<0.01); iv) WT C57BL/6×IL-12 KO (NS); v) WT 129×IFN-I receptor KO (NS). Results are representative of two or more independent experiments.

Discussion

Sufficient amounts of pathogen-derived adjuvant to mature APC and antigen to trigger T cells are possibly among the critical steps required for the differentiation and proliferation of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. However, during infection with different pathogens, it is not clear the point at which the amount of adjuvant and antigen reach the necessary threshold to induce APC maturation and T cell activation. Considering that in most cases the initial pathogen inoculum is limited, pathogen multiplication may be a critical step in this process. In our experimental model, after infection with viable irradiated parasites of T. cruzi, we were unable to detect differentiation and proliferation of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5). This result suggests that T. cruzi multiplication is critical to generate sufficient amounts of parasite adjuvant for the maturation of APC, and antigens for T cell activation. Our result contrasts with the data published using sporozoites of P. yoelii. In this case, relatively small doses (104–105 parasites per mouse) of non-replicating radiation-attenuated parasites efficiently prime effector/protective CD8+ T cells [16]. As for Listeria, non-replicating irradiated bacterias were also used during priming of effector/protective CD8+ T cells. However, large doses of bacteria (109 per mouse) were employed. This inoculum size of radiation-attenuated bacterias was considerably higher than the inoculum of 104 non-irradiated bacterias per mouse used to prime protective CD8+ T cells [17].

While the notion that the timing of accumulation of pathogen-derived antigen/adjuvant may influence the kinetics of expansion of effector CD8+ T cells appears to be reasonable, few experimental models provide an opportunity to evaluate this important aspect of the CD8+ T cell response. Our initial observation that increasing doses of T. cruzi caused an acceleration of T. cruzi parasitemia without increasing mouse susceptibility provided a suitable experimental model to study this issue. As observed with T. cruzi infection, an inverse relationship was described between the inoculum size of influenza virus and the timing of accumulation of viral load in the lung. However, in this experimental model, the rapid increase in the viral load augmented the apoptosis of CD8+ T cells mediated by Fas/FasL interaction, causing a reduction in the in vivo cytotoxicity mediated by CD8+ T cells and and increased death rate in mice which received larger viral doses [18]. Differently, in our T. cruzi model we observed that increasing the size of parasite inoculum accelerated the parasitemia and the timing of differentiation and expansion of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3). However, the different doses of parasite did not modified the final magnitude of the specific CD8+ T cell response as measured by the in vivo cytotoxicity or the ELISPOT assay (Fig. 3). Therefore, we concluded that differently to the influenza virus system, no inhibitory activity was generated in T. cruzi infection by the fast pace of parasite adjuvant/antigen accumulation in C57BL/6 mice.

The curves of parasitemia observed in WT C57BL/6 or CD8 KO mice challenged with different parasite doses, strongly suggest that protective CD8+ T cells are important for mouse survival only after the parasitemia reached a peak (Fig. 1 and 2). Until that day, the amounts of parasites in the blood of both, WT C57BL/6 and CD8 KO mice, were similar (Fig. 2, ref. 13). After the peak parasitemia, a rapid reduction in the number of blood parasites was observed in WT mice while CD8 KO mice failed to control parasite growth, became severely ill, and eventually died. Confirmation of the importance of CD8+ T cells in the period after the peak parasitemia was obtained in experiments in which we estimated the presence of cytotoxic T cells in vivo. For example, while the peak parasitemia of mice challenged with 105 parasites was reached 5 days post-infection, no peptide-specific cytotoxicity was detected at that day (Fig. 3A). However, 5 days later, the in vivo cytotoxicity was already 100% indicating that specific CD8+ T cells expanded vigorously during that period. Essentially the same sequence of events is observed in mice challenged with different doses of parasites. Based on these observations, we concluded that following challenge of naïve hosts with parasites of the Y strain of T. cruzi, the differentiation and expansion of splenic antigen-specific effector CD8+ T cells occurs after the peak parasitemia. These results are in close agreement with the data published by us and others using 4 different T. cruzi epitopes in two different mouse strains [13], [14]. We consider that our observations are consistent with the interpretation that the amount of T. cruzi antigen available before the peak of parasitemia is limited. When the parasitemia reaches its peak, the threshold for the level of adjuvant/antigen requirement may be achieved and only then, the triggering and fast activation of naïve CD8+ T cells may occur. Studies performed in mice infected with LCMV or L. monocytogenes described comparable timing for expansion of specific CD8+ T cells i.e., the peak of viral or bacterial numbers occurs approximately 2–3 days after infection. The peak of CD8+ T cell response was approximately 5 days later at day 7–8th post-infection [1], [2].

In the last part of our study, considering that a rapid induction of T. cruzi-specific CD8+ T cells occurred after administration of a large inoculum of parasites, we evaluated the importance that certain molecules/cells may have on differentiation/proliferation and effector function of specific CD8+ T cells following T. cruzi infection. For this purpose, we used genetically deficient mouse strains that are described as highly susceptible to infection with T. cruzi such as MHC-II KO, CD4 KO, IL-12 KO and perforin KO [13], [19]–[22]. MHC II KO or CD4 KO mice failed to develop peptide-specific cytotoxicity. We therefore concluded that MHC II-restricted CD4+ T cells are important for the maturation and/or expansion of T. cruzi specific cytotoxic CD8+ T cells.

Our results indicating that CD8+ T cells responses against T.cruzi are critically dependent on CD4+ T cells differ from most pathogens. Following viral or bacterial infections, the maturation and expansion of specific CD8+ T cells are not critically dependent on CD4+ T cells [23]–[29]. Similarly, CD4+ T cells are not required for the initial expansion of CD8+ T cells specific for epitopes expressed by the protozoan parasites P. yoelii or T. gondii [11], [30], [31]. The precise role for MHC II-restricted CD4+ T cells during the process of CD8+ T cell activation in our model has yet to be investigated. An intriguing possibility is that CD4+ T cells can license dendritic cells for the activation of highly cytotoxic CD8+ T cells detected by an in vivo assay [32].

Using IL-12 or IFN-I receptor KO mice, we observed that neither IL-12 nor IFN type I are critically important for the efficient maturation and expansion of T. cruzi-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. Our results contrasts with previous observation that IL-12 can provide an important third signal that, in addition to the engagements of TCR-MHC and CD28-B7, it could provide an optimal environment for the efficient cytotoxic CD8+ T cells differentiation and expansion [33]–[35].

Perforin KO mice were also severely impaired in their ability to eliminate peptide-coated targets in vivo. The low level killing detected in the absence of perforin may represent the contribution of perforin-independent killing mechanisms. Considering our previous results indicating that perforin KO mice are highly susceptible to infection with parasites of the Y strain of T. cruzi, we propose that the perforin-dependent granule exocytosis pathway represent an important mechanism of protection against T. cruzi infection. These results are in agreement with some viral models describing perforin as a key molecule for resistance against viral infection and mediating in vivo lysis of peptide-coated target cells [36], [37]. However, they differ with the observations made for other protozoan parasites in which perforin KO mice have been shown to develop protective CD8+ T cell mediated immunity [38]–[40].

In summary, our study provides new insights regarding the requirements for the differentiation and expansion of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells during experimental infection with a human protozoan parasite. Using this experimental model, we determined the importance of parasite load and MHC-II restricted CD4+ T cells for the maturation and expansion of highly cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. Also, it established an important role for perforin as a mediator of the in vivo cytotoxicity against parasite-infected cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thanks Dr. Fidel Zavala (Johns Hopkins University) for carefully reviewing the manuscript. The authors are in debt with Dr. Maria L. Juliano (UNIFESP-EPM) and Marcus L. Penido (UFMG) for kindly providing the peptide used in this study.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, and The Millennium Institute for Vaccine Development and Technology (CNPq - 420067/2005-1). FT is a recipient of a fellowship from FAPESP. PMP and MMR are recipients of fellowships from CNPq.

References

- 1.Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. Memory CD8 T-cell differentiation during viral infection. J Virol. 2004;78:5535–5545. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.5535-5545.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harty JT, Badovinac VP. Influence of effector molecules on the CD8+ T cell response to infection. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:360–365. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00333-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsuji M, Zavala F. T cells as mediators of protective immunity against liver stages of Plasmodium. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:88–93. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(02)00053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butz EA, Bevan MJ. Massive expansion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells during an acute virus infection. Immunity. 1998;8:167–175. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80469-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murali-Krishna K, Altman JD, Suresh M, Sourdive DJ, Zajac AJ, et al. Counting antigen-specific CD8 T cells: a reevaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity. 1998;8:177–187. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Busch DH, Pilip I, Pamer EG. Evolution of a complex T cell receptor repertoire during primary and recall bacterial infection. J Exp Med. 1998;188:61–70. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pope C, Kim SK, Marzo A, Masopust D, Williams K, et al. Organ-specific regulation of the CD8 T cell response to Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Immunol. 2001;166:3402–3409. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrington LE, Most R, Whitton JL, Ahmed R. Recombinant vaccinia virus-induced T-cell immunity: quantitation of the response to the virus vector and the foreign epitope. J Virol. 2002;76:3329–3337. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.7.3329-3337.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sano G, Hafalla JC, Morrot A, Abe R, Lafaille JJ, et al. Swift development of protective effector functions in naive CD8+ T cells against malaria liver stages. J Exp Med. 2001;194:173–180. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.2.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwok LY, Lutjen S, Soltek S, Soldati D, Busch D, et al. The induction and kinetics of antigen-specific CD8 T cells are defined by the stage specificity and compartmentalization of the antigen in murine toxoplasmosis. J Immunol. 2003;170:1949–1957. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Faassen H, Dudani R, Krishnan L, Subash S. Prolonged Antigen Presentation, APC-, and CD8+ T Cell Turnover during Mycobacterial Infection: Comparison with Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol. 2004;172:3491–3500. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luu RA, Gurnani K, Dudani R, Kammara R, van Faassen H, et al. Delayed Expansion and Contraction of CD8+ T Cell Response during Infection with Virulent Salmonella typhimurium. J Immunol. 2006;177:1516–1525. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tzelepis F, de Alencar BC, Penido ML, Gazzinelli RT, Persechini PM, et al. Distinct kinetics of effector CD8+ cytotoxic T cells after infection with Trypanosoma cruzi in naive or vaccinated mice. Infect Immun. 2006;74:2477–2481. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.4.2477-2481.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin DL, Weatherly DB, Laucella SA, Cabinian MA, Crim MT, et al. CD8+ T-Cell responses to Trypanosoma cruzi are highly focused on strain-variant trans-sialidase epitopes. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2(8):e77. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyahira Y, Murata K, Rodriguez D, Rodriguez JR, Esteban M, et al. Quantification of antigen specific CD8+ T cells using ELISPOT assay. J Immunol Methods. 1995;181:145–154. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)00327-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hafalla JC, Sano G, Carvalho LH, Morrot A, Zavala F. Short-term antigen presentation and single clonal burst limit the magnitude of the CD8+ T cell responses to malaria liver stages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11819–11824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182189999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Datta SK, Okamoto S, Hayashi T, Shin SS, Mihajlov I, et al. Vaccination with irradiated Listeria induces protective T cell immunity. Immunity. 2006;25:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Legge KL, Braciale TJ. Lymph node dendritic cells control CD8+ T cell responses through regulated FasL expression. Immunity. 2005;23:649–659. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarleton RL, Grusby MJ, Postan M, Glimcher LH. Trypanosoma cruzi infection in MHC-deficient mice: further evidence for the role of both class I- and class II-restricted T cells in immune resistance and disease. Int Immunol. 1996;8:13–22. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michailowsky V, Silva NM, Rocha CD, Vieira FQ, Lannes-Vieira J, et al. Pivotal role of interleukin-12 and interferon-gamma axis in controlling tissue parasitism and inflammation in the heart and central nervous system during Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1723–1733. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63019-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galvao Da Silva AP, Jacysyn JF, Abrahamsohn IA. Resistant mice lacking interleukin-12 become susceptible to Trypanosoma cruzi infection but fail to mount a T helper type 2 response. Immunology. 2003;108:230–237. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01571.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muller U, Sobek V, Balkow S, Holscher C, Mullbacher A, et al. Concerted action of perforin and granzymes is critical for the elimination of Trypanosoma cruzi from mouse tissues, but prevention of early host death is in addition dependent on the FasL/Fas pathway. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:70–78. doi: 10.1002/immu.200390009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buller RM, Holmes KL, Hugin A, Frederickson TN, Morse HC., III Induction of cytotoxic T-cell responses in vivo in the absence of CD4 helper cells. Nature. 1987;328:77–79. doi: 10.1038/328077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahemtulla A, Fung-Leung WP, Schilham MW, Kundig TM, Sambhara SR, et al. Normal development and function of CD8+ cells but markedly decreased helper cell activity in mice lacking CD4. Nature. 1991;353:180–184. doi: 10.1038/353180a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riberdy JM, Christensen JP, Branum K, Doherty PC. Diminished primary and secondary influenza virus-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in CD4-depleted Ig−/− mice. J Virol. 2000;74:9762–9765. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.20.9762-9765.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shedlock DJ, Shen H. Requirement for CD4 T cell help in generating functional CD8 T cell memory. Science. 2003;300:337–339. doi: 10.1126/science.1082305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun JC, Bevan MJ. Defective CD8 T cell memory following acute infection without CD4 T cell help. Science. 2003;300:339–342. doi: 10.1126/science.1083317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marzo AL, Vezys V, Klonowski KD, Lee SJ, Muralimohan G, et al. Fully functional memory CD8 T cells in the absence of CD4 T cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:969–975. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bevan MJ. Helping the CD8+ T-cell response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:595–602. doi: 10.1038/nri1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrot A, Hafalla JC, Cockburn IA, Carvalho LH, Zavala F. IL-4 receptor expression on CD8+ T cells is required for the development of protective memory responses against liver stages of malaria parasites. J Exp Med. 2005;202:551–560. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lutjen S, Soltek S, Virna S, Deckert M, Schluter D. Organ- and disease-stage-specific regulation of Toxoplasma gondii-specific CD8-T-cell responses by CD4 T cells. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5790–5801. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00098-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castellino F, Germain RN. Cooperation between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells: when, where, and how. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:519–540. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valenzuela J, Schmidt C, Mescher M. The roles of IL-12 in providing a third signal for clonal expansion of naive CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:6842–6849. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt CS, Mescher MF. Peptide Ag priming of naive, but not memory, CD8 T cells requires a third signal that can be provided by IL-12. J Immunol. 2002;168:5521–5529. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curtsinger JM, Lins DC, Mescher MF. Signal 3 determines tolerance versus full activation of naive CD8 T cells: dissociating proliferation and development of effector function. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1141–1151. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kagi D, Ledermann B, Burki K, Seiler P, Odermatt B, Olsen KJ, et al. Cytotoxicity mediated by T cells and natural killer cells is greatly impaired in perforin-deficient mice. Nature. 1994;369:31–37. doi: 10.1038/369031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barber DL, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. Cutting edge: rapid in vivo killing by memory CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:27–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Renggli J, Hahne M, Matile H, Betschart B, Tschopp J, et al. Elimination of P. berghei liver stages is independent of Fas (CD95/Apo-I) or perforin-mediated cytotoxicity. Parasite Immunol. 1997;19:145–148. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1997.d01-190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Denkers EY, Yap G, Scharton-Kersten T, Charest H, Butcher BA, et al. Perforin-mediated cytolysis plays a limited role in host resistance to Toxoplasma gondii. J Immunol. 1997;159:1903–1908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morrot A, Zavala F. Effector and memory CD8+ T cells as seen in immunity to malaria. Immunol Rev. 2004;201:291–303. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]