Abstract

Previous research indicates that dopamine controls both the speed of an internal clock (Maricq and Church, 1983) and sharing of resources between the timer and other cognitive processes (Buhusi, 2003). For example, dopamine agonist methamphetamine increases the speed of an internal clock and resets timing after a gap, while dopamine antagonist haloperidol decreases the speed of an internal clock and stops timing during a gap (Buhusi and Meck, 2002a). Using a 20-s peak-interval procedure with gaps we examined the acute effects of clozapine (2.0 mg/kg i.p.), which exerts differential effects on dopamine and serotonin in the cortex and striatum, two brain areas involved in interval timing and working memory. Relative to saline, clozapine injections shifted the response functions leftward both in trials with and without gaps, suggesting that clozapine increased the speed of an internal clock and facilitated the maintenance of the pre-gap interval in working memory. These results suggest that clozapine exerts effects in different brain areas in a manner that allows for the pharmacological separation of clock speed and working memory as a function of peak trials without and with gaps.

Keywords: Clozapine, Dopamine, Gap, Interval timing, Lever-pressing, Peak-interval procedure, Rat, Serotonin

1. Introduction

Bees, fish, turtles, birds, rodents, and primates (Buhusi and Meck, 2005; Church, 1984; Fortin, 2003; Gibbon et al., 1997; Matell and Meck, 2000) process temporal information as if they use a stopwatch (Church, 1978). Church’s stopwatch metaphor encompasses data showing that animals’s internal clock times up in a linear fashion (Church, 1984; Gibbon and Church, 1981), can be used to time signals from different modalities both sequentially and simultaneously (Meck and Church, 1984; Olton et al., 1988) and can be stopped temporarily and reset on command (Church, 1978, 1984; S. Roberts and Church, 1978). This stopwatch metaphor is instantiated by the information-processing (IP) version (Church, 1984; Gibbon et al., 1984) of Scalar Timing Theory which is the leading model of interval timing (Allan, 1998; Church, 1984, 2003; Wearden, 1999, 2005). According to this model, pulses emitted at regular intervals by a pacemaker (Fraisse, 1957; Francois, 1927; Hoagland, 1933; Woodrow, 1930) are stored in an accumulator whose content represents the current subjective time (Treisman, 1963). The number of pulses in the accumulator is stored in long-term memory to inform subsequent behavior. In the model, interval timing behavior is controlled by the ratio of the current subjective time to the learned criterion, thus accounting for the scalar property (Gibbon, 1977).

The success of the IP model of interval timing is due in large part to the modularity of the clock, memory, and decision stages of the model which allows for ample theoretical and experimental evaluations and development at mathematical (Church et al., 1994; Gibbon and Church, 1981), behavioral (Church, 1978, 1984; Church and Deluty, 1977) and neurophysiological levels (Maricq and Church, 1983; Maricq et al., 1981; Olton et al., 1987; Olton et al., 1988), as well as for extensions to other fields such as counting (Meck and Church, 1983; Meck et al., 1985) and magnitude processing (Gallistel and Gelman, 1992).

To evaluate the behavioral and neurophysiological properties of the internal stopwatch, Church (1978) extended Catania’s (1970) peak-interval (PI) procedure to include trials with brief breaks (gaps). In the PI procedure with gaps (gap procedure), subjects are exposed to three types of trials: fixed-interval (FI) trials, PI trials and gap trials. In FI trials subjects are presented with a signal for an FI; the first response after the FI terminates the to-be-timed signal, and triggers the delivery of reinforcement. In PI trials, the to-be-timed signal is presented for about three times the duration of the FI, and subject’s responses are not reinforced; in these trials the mean response rate reaches a peak about the time when subjects were (sometimes) reinforced (Catania, 1970). Gap trials are similar to PI trials, but the to-be-timed signal is interrupted for a brief break (gap); typically, in gap trials the mean response rate increases in the pre-gap interval, declines during the gap, and then increases again after the gap, reaching a peak that is delayed relative to the peak-time during standard PI trials (Church, 1978). A major benefit of the PI procedure with gaps (Church, 1978) is that timing and its flexible use are evaluated in separate trials.

This property has been used extensively to evaluate the mechanisms of the internal stopwatch at the theoretical, neurophysiological, and behavioral level. For example, the use of the PI procedure with gaps allowed for the development and evaluation of a multitude of putative behavioral hypotheses on the underlying mechanism of the flexible use of interval timing, from the seminal switch hypothesis (Church, 1978; Gibbon et al., 1984), to the more recent memory decay hypothesis (Cabeza de Vaca et al., 1994), ambiguity hypothesis (Kaiser et al., 2002; S. Roberts and Church, 1978; Sherburne et al., 1998), and time-sharing hypothesis (Buhusi, 2003; Fortin and Masse, 2000). The use of the PI procedure with gaps also allowed for the mapping the Information Processing model of interval timing (Church, 1984; Gibbon et al., 1984) onto brain structures and neurotransmitter systems. For example, the pacemaker component was shown to be dependent on the dopaminergic (DA) system (Buhusi and Meck, 2005; Maricq and Church, 1983; Meck, 1996), while the long-term memory stage is affected by cholinergic manipulations (Meck and Church, 1987a, 1987b; Meck et al., 1987). Moreover, lesions of the hippocampal system were shown to interfere with working memory for time (Buhusi and Meck, 2002b; Meck et al., 1984). More importantly for this paper, a recent study (Buhusi and Meck, 2002a) showed that the clock stage and the working-memory stage of the IP model can be dissociated pharmacologically in the PI procedure with gaps, because DA drugs shift the response functions in opposite direction in trials with and without gaps. While these data implicate DA as a major substrate for the internal clock, data obtained in other interval timing paradigms (Body et al., 2006) suggest that other neurotransmitter systems—such as serotonin (5-HT)—might also contribute to interval timing behavior.

To address this issues we used the PI procedure with gaps to evaluate the acute effects of systemic administration of clozapine—a drug acting both on the DA and 5-HT systems—on interval timing. We found that clozapine shifted the response functions in the same direction (leftward) both in trials without gaps—suggestive of an effect on the clock stage of the internal stopwatch—as well as during gap trials—suggestive of an effect on the working-memory stage of the internal stopwatch. Together with results reviewed above, these data suggest that the PI procedure with gaps (Church, 1978) is an ideal tool to dissociate the mechanisms of the internal stopwatch at the behavioral and pharmacological level.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

The subjects were ten Sprague-Dawley male rats six-months old at the beginning of the experiment. Rats were housed in pairs in a temperature-controlled room, under a 12/12-h light-dark cycle. Water was given ad lib in the home cages. The rats were maintained at 85% of their ad lib weight by restricting access to food (Rodent Diet 5001, PMI Nutrition International, Inc., Brentwood, MO). Manipulations were carried out in accordance with standard procedures approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Duke University.

2.2. Apparatus

The apparatus consisted of 10 standard operant boxes (MED Associates, Inc., Model ENV-007) housed in sound attenuating cubicles (Med Associates, Inc., Model ENV-019). Each operant box had inside dimensions of approximately 24 x 31 x 31 cm. The top, sidewall, and door were 6 mm clear acrylic plastic. The front and back walls were stainless steel, and the floor was comprised of 19 parallel stainless steel bars. Each box was equipped with three response levers (two retractable and one fixed, Med Associates, Inc., Model ENV-112) situated on the front wall of the box. All experimental procedures used only the left lever. According to the schedule, 45-mg Noyes precision food pellets (Research Diets, Inc., New Brunswick, NJ) were delivered in a food cup situated on the front wall, 1 cm above the grid floor, under the center lever, by a pellet dispenser (MED Associates, Inc., Model ENV-203). The visual stimulus used in this experiment was a 28-V 80-mA 2500-lux house light (Med Associates, Inc., Model ENV-215) mounted at the center-top of the front wall. The brightness of the light stimulus was measured with a light meter (Lutron Electronics Co., Coopersburg, PA, Model LX-102), positioned 1 cm from the house light. A 66-dB sound produced by a fan was present throughout all procedures. The intensity of the fan was measured with a sound level meter (Realistic Radio Shack, Model 33-2050) from the center of the (silent) box.

2.3. Autoshaping

The rats were autoshaped to lever press for 3 daily sessions. The response lever was retracted for 1 s and re-inserted into the box followed by the delivery of a food pellet every 60 s independent of responding. In addition, each lever-press was reinforced on a continuous reinforcement (CRF) schedule, and the lever was not retracted. This procedure continued for a maximum of 1 hr or until the rat had received 60 food pellets. During the rest of the experiment the response lever was always inserted into the box for the entire session.

2.4. FI procedure

Rats were randomly assigned to two groups, Standard (N=5) and Reversed (N=5). For the rats in the Standard group the to-be-timed signal was the presence of the visual stimulus and the ITI was dark, while for the the rats in the Reversed group the to-be-timed signal was the absence of the visual stimulus and the ITI was illuminated (Buhusi and Meck, 2000). In each daily session all rats received 64 FI trials. The first lever press 20 s after the onset of the to-be-timed signal was reinforced by the delivery of a food pellet and turned the to-be-timed signal off for the duration of the random ITI. Trials were separated by a 60 ± 30-s random ITI. Statistical analyses of the accuracy of timing (peak time, parameter t0, see Data collection and analysis), precision of timing (parameter b), and peak response rate (parameter a+d) failed to reveal differences between the two groups, so data were collapsed across this variable.

2.5. PI procedure

After 9 sessions of FI training, rats received 22 daily sessions of PI training. During each session the rats received 32 FI trials randomly intermixed with 32 non-reinforced probe trials in which the to-be-timed signal (according to the group) was turned on for a duration three times longer than the FI time, before being terminated irrespective of responding. Trials were separated by a 60 ± 30-s random ITI.

2.6. Gap sessions

In each of the next 6 daily sessions rats received 32 FI trials randomly intermixed with 32 non-reinforced test trials (8 PI trials and 8 trials for each of the three types of gaps). Three types of gaps were tested: EARLY (5-s gap presented 5-s from signal onset), LONG (10-s gap presented 5-s from signal onset), and LATE (5-s gap presented 10-s from signal onset). During gap trials, the to-be-timed stimulus was turned on for the pre-gap duration and off for the duration of the gap. At the offset of the gap the to-be-timed signal was reinstated for a duration that matched the duration used in the PI trials, and then terminated independently of responding for the random duration of the ITI. Trials were separated by a 60 ± 30-s random ITI.

2.7. Drug administration

Fifteen minutes before the last 2 PI sessions each rat was injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with saline. Also, fifteen minutes before each of the 6 gap sessions, each rat was injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with either saline or with clozapine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in saline at a dose of 2 mg/kg. Drug sessions alternated between saline and clozapine (counterbalanced) to reduce the sensitization and tolerance effects as well as to prevent possible effects of the drugs on memory storage (Meck, 1983, 1996). Data from the 3 gap sessions of saline administration and 3 gap sessions of clozapine administration were analyzed as follows.

2.8. Data collection and analysis

The experimental procedures were controlled through a MED Associates interface connected to an IBM-PC compatible computer running a MED-PC software system (MED-Associates, 1999). Responses were recorded in real time. Only data recorded during test trials were used in the analyses. Additional programs were used to extract the daily mean response rates and individual peak times necessary for obtaining the performance measures described below.

Data were used to estimate the peak time, peak rate, and precision of timing of the response functions of each rat from the collapsed data from the three gap sessions with saline and the collapsed data from the three gap sessions with clozapine. The number of responses (in 2-s bins) was averaged daily over trials, to obtain a mean response rate for each rat. Further analyses were conducted on the data from an interval twice as large as the fixed interval (i.e., 40 s), starting at the onset of the signal (for data in PI trials) or at the offset of the gap (for gap trials). The mean response rate in the interval of interest was fit using the Marquardt-Levenberg (Marquardt, 1963) iterative algorithm to find the coefficients (parameters) of the following Gaussian+linear equation

| (Equation 1) |

that gave the “best fit” (least squares minimization) between the equation and the data, as described in Buhusi and Meck (2000). The iterative algorithm provided parameters a, b, c, d and t0. Parameter t0 was used as an estimate of timing accuracy (peak time of responding), a+d was used as an estimate of the peak rate of response, and parameter b was used as an estimate of the precision of interval timing. For data in gap trials, a shift in response relative to PI trials was computed by subtracting from the peak time in gap trials the peak time in PI trials and the duration of the gap. The parameters t0, b, and a+d, and the peak time shift were submitted to statistical analyses. Because the analyses failed to suggest a significant effect of session during gap testing, data from gap sessions were collapsed over sessions and re-fit using the Marquardt-Levenberg algorithm.

All statistical tests were evaluated at a significance level of 0.05.

3. Results

Statistical analyses of response accuracy (peak time, parametet t0), precision (parameter b) and rate (parameter a+d) failed to reveal a reliable effect of the Group variable (Standard, Reversed), or interactions with the other variables. For example, a mixed ANOVA of the accuracy (peak time parameter) of the response function with between-factor Group (Standard, Reversed) and repeated-factors Drug (Saline, Clozapine) and Trial type (PI, Early gap, Late gap, Long gap) failed to reveal a reliable effect of Group or interactions with the Group variable, Fs < 4.93, p>0.05. Similarly, a mixed ANOVA of precision (width) of the response function with between-factor Group and repeated-factors Drug and Trial type failed to reveal any reliable effects or interactions, Fs < 2.66, p>0.05. Finally, a mixed ANOVA of the rate of response with between-factor Group and repeated-factors Drug and Trial type failed to reveal any reliable effect of Group or interactions with the Group variable, Fs < 1.78, p>0.05. Therefore, in further analyses data were collapsed across the Group variable. A summary of performace is given in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of performance.

Peak time is given by parameter t0 and is measured from the begining of trial. The width of the function is given by parameter b. PI: peak-interval. SAL: saline; CLZ: clozapine.

| Trial type | Drug | Peak time ± SEM | Width ± SEM | R2 ± SEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI

|

SAL

CLZ |

20.64 ± 0.43

18.30 ± 0.94 |

8.1 ± 0.43

9.18 ± 0.45 |

0.95 ± 0.01

0.85 ± 0.03 |

| EARLY GAP

|

SAL

CLZ |

30.53 ± 0.76

25.53 ± 1.09 |

8.09 ± 0.89

9.7 ± 1.09 |

0.90 ± 0.02

0.82 ± 0.03 |

| LONG GAP

|

SAL

CLZ |

36.19 ± 0.96

32.49 ± 1.01 |

8.67 ± 0.97

10.25 ± 0.91 |

0.89 ± 0.03

0.84 ± 0.03 |

| LATE GAP

|

SAL

CLZ |

35.11 ± 1.72

29.5 ± 1.23 |

9.49 ± 1.37

9.32 ± 1.25 |

0.78 ± 0.03

0.80 ± 0.04 |

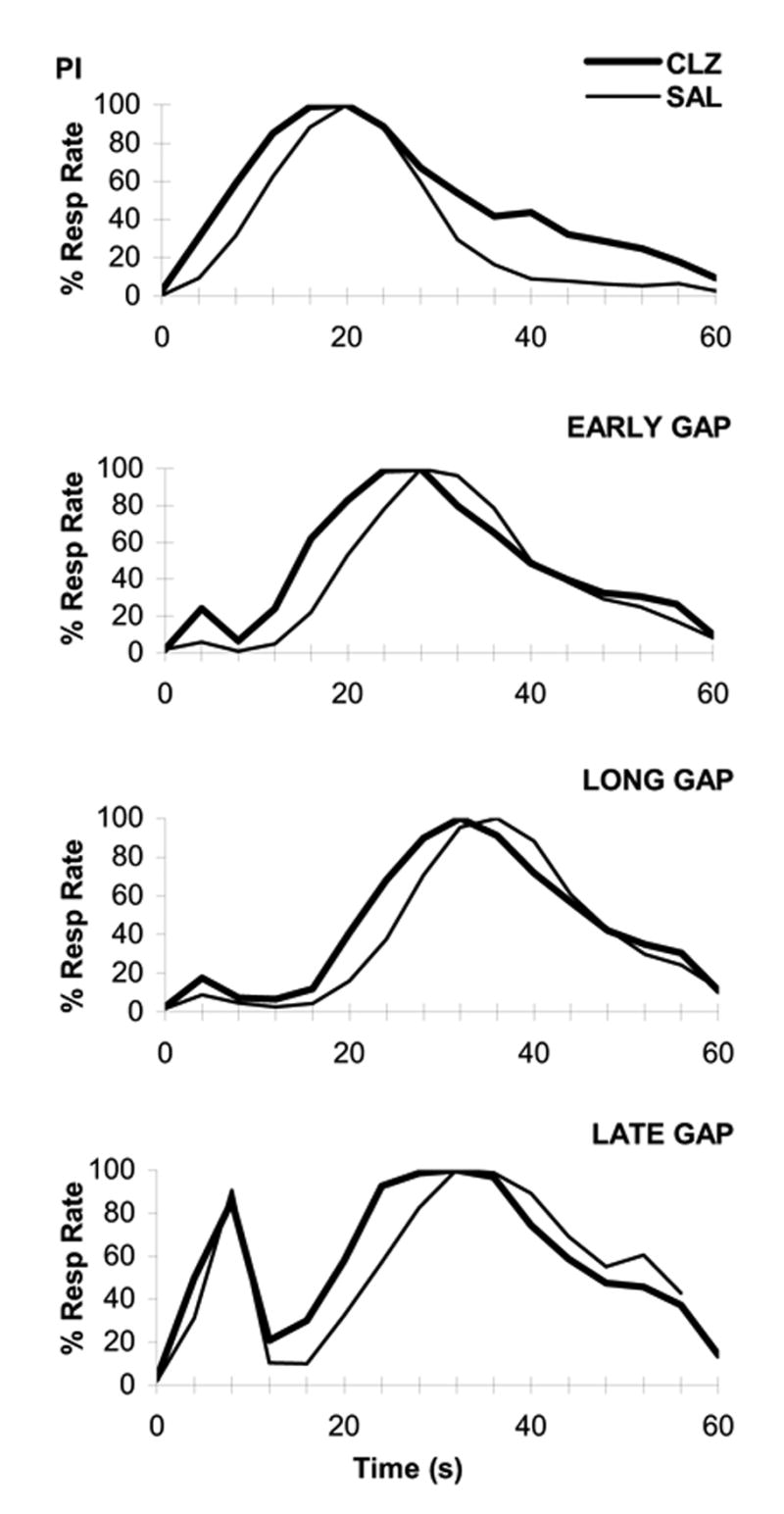

The mean percent maximum response rate in PI and gap trials from the saline and clozapine gap sessions is shown in Figure 1. The upper panel of Figure 1 shows that in PI trials the mean response rate peaked about the criterion time (20s) under saline, but earlier under clozapine. A repeated-measures ANOVA of the accuracy of timing (peak time) with factor Drug (Saline, Clozapine) revealed a reliable effect of clozapine, F(1,9)=13.26. In PI trials, acute, systemic administration of clozapine reliably decreased the peak time of the response rate from 20.63 ± .43 s under saline to 18.30 ± .94 s under clozapine. These analyses indicate that rats acquired the interval-timing task with a high degree of accuracy, and that under clozapine their response peaked earlier than under saline, possibly due to an increase in the speed of the internal stopwatch.

Figure 1. Effect of clozapine on interval timing in the PI procedure with gaps.

Percent maximum response rate in PI trials (upper panel) and gap trials (lower three panels) under acute administration of saline (SAL) and clozapine (CLZ).

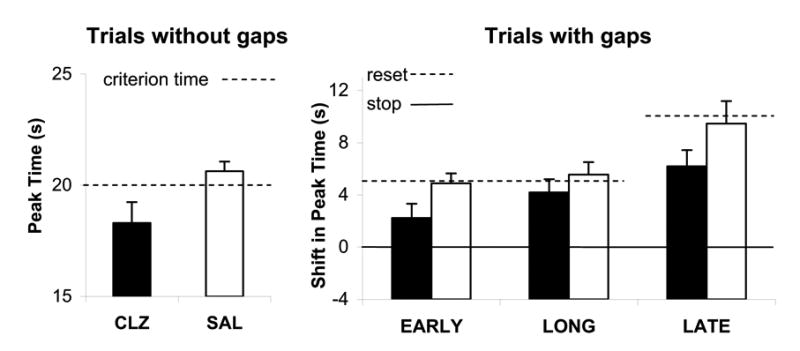

The mean percent maximum response rate in Early, Long, and Late gap trials in the saline and clozapine gap sessions is shown in the lower three panels of Figure 1, which indicate a leftward shift in response functions under clozpaine relative to saline in all gap trials. To evaluate the effect of clozapine in gap trials relative to PI trials, we computed a shift in peak time in gap trials by subtracting both the peak time in PI trials and the duration of the gap from the peak time in gap trials. The estimated shift in peak time in gap trials relative to PI trials is shown in the right panel of Figure 2. A repeated-measures ANOVA of the shift in peak time in gap trials relative to PI trials with repeated-factors Drug (Saline, Clozapine) and Gap (Early, Long, Late) revealed a reliable effect of clozapine, F(1,9)=7.87, and Gap, F(2,18)=14.61, but no interaction between these variables. As shown in the right panel of Figure 2, relative to saline, clozapine administration reliably decreased the shift in peak time (towards stopping timing) from 4.89 ± .76 s to 2.23 ± 1.09 s for Early gaps, from 5.55 ± .96 s to 4.19 ± 1.01 s for Long gaps, and from 9.47 ± 1.72 s to 6.19 ± 1.23 s for Late gaps.

Figure 2. Effect of systemic administration of clozapine on accuracy of timing in the PI procedure with gaps.

Accuracy of timing (response peak time) under acute, systemic administration of saline (SAL, open bars) and clozapine (CLZ, closed bars) was estimated by fitting a Gaussian-like function to individual response functions in trials without gaps (left panel) and trials with EARLY, LONG, and LATE gaps (right panel). The shift in peak time in gap trials (right panel) was computed by subtracting the estimated peak time in PI trials and the duration of the gap from the estimated peak time in gap trials. A null shift is indicative of the use of a stop rule, and a shift equal to the pre-gap duration is indicative of the use of a reset rule.

A summary of the effect of clozapine on the accuracy of timing in the PI procedure with gaps is presented in Figure 2. The left panel of Figure 2 shows that acute administration of clozapine decreases the response peak time, an effect consistent with an increase in the speed of the internal clock. The right panel of Figure 2 indicates that acute administration of clozapine reliably decreases the shift in peak time in gap trials relative to PI trials. The reported descrease of the shift in peak time under clozapine relative to saline is above and beyond the effect of clozapine in PI trials, and is consistent with clozapine increasing the capability of rats to maintain the pre-gap duration in working memory, or, in other words, with clozapine decreasing the rate of working-memory decay during the gap (Buhusi, 2003).

Moreover, a repeated-measures ANOVA of precision (width) of the response function in the saline and clozapine gap sessions with factors Drug (Saline, Clozapine) and Trial type (PI, Early gap, Long gap, Late gap) failed to reveal any reliable effects or interactions, Fs < 1.66, p>0.05, suggesting that the precision of timing was not affected either by drug or condition. In short, response functions were simply shifted rightward by the gap relative to PI trials, and leftward by clozapine relative to saline, suggesting that both the gap and clozapine affect the timing of the response without affecting the precision of timing.

Finally, a repeated-measures ANOVA of response rate in the collapsed data from the six gap sessions with factors Drug (Saline, Clozapine) and Trial type (PI, Early gap, Long gap, Late gap) revealed a reliable effect of Drug, F(1,9)=6.70, Trial type, F(3,27)=16.87, and Drug × Trial type interaction, F(3,27)=11.28. Relative to saline, clozapine reliably decreased the response rate in PI trials, F(1,9)=17.07, from 64.63 ± 9.02 resp / min to 40.79 ± 6.29 resp / min. However, clozapine did not reliably change the (already decreased) response rate in gap trials, F(1,9)=2.48. Relative to PI trials, the response rate was reliably reduced in gap trials, to an average of 36.17 ± 5.93 resp / min under saline, and 30.90 ± 5.20 resp / min under clozapine.

4. Discussion

Clozapine is an atypical antipsychotic, with a broad-spectrum pharmacological profile. It binds to dopaminergic, serotonergic, H1 histaminergic, muscarinic acethylcholine, and α1- and α2-adrenergic receptors (King and Waddington, 2004; Leysen, 2000). Clozapine has relatively low affinity for the D2 receptors in the striatum (Xiberas et al., 2001), while its in vitro affinity for the D4 receptors is much higher than that for D1, D2, D3, and D5 receptors (Coward, 1992; Kusumi et al., 1995). This accounts for the efficacy of clozapine in alleviating the symptoms of schizophrenia without causing extra pyramidal side effects (Farde et al., 1992), because D4 receptor density is high in the frontal cortex and amygdala but relatively low in the basal ganglia (De La Garza and Madras, 2000; Tarazi et al., 1998). The effect of clozapine in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex may be related to its blockade of α2-adrenoceptors , which has been proposed to be important for clozapine’s therapeutic effect (Blake et al., 1998; Hertel et al., 1999; Leysen, 2000).

It has been suggested that the effect of clozapine and other atypical antipsychotic drugs, all of which are relatively more potent as 5-HT2A than dopamine D2 antagonists, to improve negative symptoms and cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia, is due to an increase in cortical dopamine release by an interaction with the serotonergic system (Ichikawa et al., 2001; Meltzer et al., 2003). Indeed, besides its DA action, clozapine is a potent blocker of the 5-HT2 receptor and a partial agonist of the 5-HT1A receptor (Ichikawa et al., 2001; Meltzer, 1999; Meltzer et al., 1989). The blockade of the 5-HT2A receptor has been shown to either directly—or indirectly by activation of the 5-HT1A—increase DA release in the medial prefrontal cortex (Chou et al., 2003; Ichikawa et al., 2001; Meltzer et al., 2003; Rollema et al., 1997).

Because interval timing is dependent upon DA–glutamate interactions in corticostriatal circuits (Buhusi and Meck, 2005; Matell et al., 2004; Matell and Meck, 2004; Matell et al., 2003; Meck, 1996, 2005, 2006a, 2006b), these findings suggest that clozapine may affect timing and time perception directly by changes in the mechanisms of an internal stopwatch (MacDonald and Meck, 2005) or by affecting motivational systems (Cilia et al., 2001; Mobini et al., 2000). The present experiment examined the effect of i.p. acute administration of clozapine 2mg/kg on timing in the Standard and Reversed PI procedure with gaps. We found that clozapine administration resulted in a horizontal leftward shift of the response functions relative to saline administration in PI trials (trials without gap). These data are consistent with an effect of clozapine on the clock stage of the internal stopwatch (MacDonald and Meck, 2005) or with an increase in reinforcer efficacy, as assessed by performance in progressive ratio schedules (Cilia et al., 2001; Mobini et al., 2000). Although the latter interpretation can not be ruled out, the fact that clozapine was shown to produce a leftward shift proportional to the timed criterion in a tri-peak procedure (MacDonald and Meck, 2005), strongly suggests that clozapine increases the speed of the internal stopwatch.

Moreover, we found that clozapine administration also resulted in a horizontal leftward shift of the response functions relative to saline in gap trials, suggestive of an effect on the flexible use of the internal stopwatch. Importantly, Figure 1 shows that the leftward shift produced by clozapine administration is larger in gap trials (lower three panels) than in PI trials (upper panel). To evaluate this effect, when computing the shift in peak time in gap trials we subtracted both the peak time in PI trials and the duration of the gap from the peak time in gap trials. The resulted shift in peak time was found reliably smaller under clozapine than under saline (right panel of Figure 2), above and beyond the effect of the drug when the to-be-timed signal is not interrupted by a gap (left panel of Figure 2). Therefore, these results differentiate two separate effect of clozapine on interval timing in trials with and without gaps.

In regard to the interpretation of the effects in gap trials, a number of hypothese have been put forward at a behavioral level. To account for data showing that rats tend to maintain the pre-gap duration in working memory during the gap, and resume timing where they left off following the gap (Church, 1978; S. Roberts, 1981)—a response rule called stop—Church (1978; Gibbon et al., 1984) proposed that the pacemaker is connected to the accumulator by means of a putative switch, that is closed during the to-be-timed signal and open during the gap, thus allowing, or not, pulse accumulation. In contrast to rats, birds tend to restart the entire timing process after the gap, a rule called reset (Bateson and Kacelnik, 1998; Brodbeck et al., 1998; Cabeza de Vaca et al., 1994; W. A. Roberts et al., 1989). To acount for both the stop and reset behavior, Cabeza de Vaca et al. (1994) proposed that subjective time—stored in working memory—decays passively during the gap. Moreover, to account for the fact that pigeons tend to stop when the gap is dissimilar from the inter-trial interval (ITI), Zentall and colleagues (Kaiser et al., 2002; Sherburne et al., 1998) proposed that subjects may perceive the gap as an ambiguous, ITI-like event. Finally, a different interpretation of these results is that timing in the gap procedure depends on the balance of two processes: time accumulation and working-memory decay controlled by the salience of the interrupting event (Buhusi, 2003; Buhusi et al., 2005). This latter view accounts not only for the stop and reset rules, but also for data indicating that non-temporal parameters of the to-be-timed event influence the response rule adopted by rats (Buhusi and Meck, 2000, 2002a; Buhusi et al., 2005), mice (Houkal et al., 2005) and pigeons (Buhusi et al., 2006; Buhusi et al., 2002) in the PI procedure with gaps and/or distracters (Buhusi and Meck, 2006a, 2006b). Therefore, the present data suggest that clozapine either (a) decreases the ability of a putative switch to open, or (b) decreases the rate of working memory decay during the gap, thus allowing for more pulse accumulation. Alternatively, clozapine might (c) decrease the perceived similarity between the gap and the ITI, or (d) decrease the perceived salience of the gap, thus promoting the use of a stop rule. More experiments need to be done before these possibilities are differentiated.

Together with the previously reported effects of the indirect DA agonist methamphetamine and the DA D2 receptor antagonist haloperidol in the PI procedure with gaps, the present data suggest that the drug effects in PI and gap trials rely on separate neurophysiological mechanisms. In similarity to another serotonin 5-HT2A/2C agonist, DOI (Asgari et al., 2006), in the present experiment clozapine was found to shift the response functions leftward in trials without gaps; a similar effect was found after administration of indirect DA agonists methamphetamine (Buhusi and Meck, 2002a) and cocaine (Matell et al., 2004). Because only one dose of clozapine was use, caution is required in interpreting the results of the present study. However, in similarity to the present results, a study using multiple doses of clozapine found a dose-dependent leftward shift in response function consistent with an increase in clock speed (MacDonald and Meck, 2005). While methamphetamine and cocaine are indirect DA agonists with major action in the striatum, clozapine has different DA effects in striatum and frontal cortex. Clozapine is a DA antagonist in the mesolimbic system, and an indirect DA agonist in the frontal cortex by its activation of the 5-HT2A receptors on DA neurons in the frontal cortex. These opposite effects in striatum and frontal cortex may account for the present data, which are consistent with the hypothesis that the clock effect of clozapine is due to an increase in DA neurotransmission in frontal cortex (Chou et al., 2003; Ichikawa et al., 2001; Meltzer et al., 2003; Rollema et al., 1997) but not in the dorsal striatum (Body et al., 2006). On the other hand, in similarity to dopamine D2 antagonist haloperidol, clozapine shifted the response functions leftward in trials with gaps, suggesting that DA antagonism in the mesolimbic system has a major role in the biological mechanisms activated in gap trials (Farde et al., 1992).

Interestingly, in the present experiment we failed to find reliable differences between the response strategies used by rats in the Standard and Reversed groups. Previous data indicates that rats tend to use different response rules when timing the presence and absence of a visual stimulus. When timing the presence of a visual stimulus (Standard gap procedure), rats tend to stop timing during the dark gap, and when timing the absence of a visual stimulus (Reversed gap procedure), rats tend to reset after the illuminated gap (Buhusi and Meck, 2000). The failure to find reliable differences between the Standard and Reversed groups in our setting may be due to the relatively low salience of the timed signal / gap. According to the time-sharing hypothesis (Buhusi, 2003), the balance between time accumulation and working-memory decay controlled by the salience of the gap, proportional to the discriminability of the gap from the to-be-timed signal (gap-signal contrast). A high gap-signal contrast promotes resetting, while a low gap-signal contrast promote stopping (Buhusi et al., 2006; Buhusi et al., 2005; Buhusi et al., 2002). Indeed Buhusi et al. (2002) manipulated the intensity of a visual stimulus in the Standard and Reversed gap procedure in rats, and found a reliable Procedure × Intensity interaction, in that the difference in response strategies bewteeen the Standard and Reversed groups increases with the intensity of the visual stimulus (Buhusi, 2003; Buhusi et al., 2005). Indeed, in our experiment we used a relatively low-intensity, 2500-lux visual stimulus, while differences between the Standard and Reversed procedure have been reported with visual stimuli of 5000-lux or more (Buhusi and Meck, 2000; Buhusi et al., 2002). An alternative explanation of these data is that the failure to to find reliable differences between the response strategies used by rats in the Standard and Reversed groups is due to a ceiling effect. Future studies using a larger range of parameters may be able to diferentiate these two possibilities.

In the present experiment clozapine shifted the response functions leftward without changes in the width of the response functions, suggesting that clozapine did not interfere with response variability; a similar result has been reported for the DA D1 and D2 receptor antagonists SCH and raclopride (Rick et al., 2006). Moreover, in accord with other reports, clozapine administration decreased the rate of response in PI trials without affecting the (already lower) rate of response in gap trials (MacDonald and Meck, 2005). Together with data indicating that DA antagonist haloperidol shifts the response functions rightward in PI trials (opposite from clozapine) but decreases the response rates in PI trials (like clozapine) (Buhusi and Meck, 2002a; Drew et al., 2003; Rick et al., 2006), and that DA agonist cocaine shifts the response functions leftward in PI trials (like clozapine) but increases the response rates in PI trials (opposite from clozapine) (Matell et al., 2004), present results suggest that (a) the timing and the rate of response are operated on by different mechanisms in the PI procedure with gaps, and (b) the timing of the response in trials with and without gaps rely on different pharmacological mechanisms, dependent on both dopamine and serotonin. A plausible explanation of the present data is that clozapine increases the speed of an internal stopwatch by increasing DA release in frontal cortex following serotonergic blockade (Chou et al., 2003; Ichikawa et al., 2001; Meltzer et al., 2003; Rollema et al., 1997), and promotes the maintenance of the pre-gap duration in working by dopaminergic blockade (Farde et al., 1992). In summary, the PI procedure with gaps, originally developed by Church (1978) to explore the behavioral mechanisms of the internal stopwatch continues to be an effective tool for differentiating the biological mechanisms underlying the flexible use of interval timing.

Acknowledgments

This paper is dedicated to the seminal theoretical and empirical contributions of Dr. Russell M. Church to the understanding of the mechanisms of interval timing using mathematical, behavioral and neurobiological methods.

A portion of this research was presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, San Diego, CA, 2001. This work was supported by grants DA13344 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and MH65561 from the National Institute of Mental Health to C.V.B.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Catalin V. Buhusi, Duke University, Center for Behavioral Neuroscience and Genomics, Dept. Psychology and Neuroscience, GSRB-2 Bldg., Rm. 3012, Box 91050, Durham, NC 27708-91050, email: catalin.buhusi@duke.edu.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allan LG. The influence of the scalar timing model on human timing research. Behav Process. 1998;44:101–117. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(98)00043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asgari K, Body S, Zhang Z, Fone KC, Bradshaw CM, Szabadi E. Effects of 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptor stimulation on temporal differentiation performance in the fixed-interval peak procedure. Behav Process. 2006;71:250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateson M, Kacelnik A. Risk-sensitive foraging: Decision making in variable environments. In: Dukas R, editor. Cognitive ecology: The evolutionary ecology of information processing and decision making. Chicago University Press; Chicago: 1998. pp. 297–341. [Google Scholar]

- Blake TJ, Tillery CE, Reynolds GP. Antipsychotic drug affinities at alpha2-adrenoceptor subtypes in post-mortem human brain. J Psychopharmacol. 1998;12:151–154. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Body S, Asgari K, Cheung TH, Bezzina G, Fone KF, Glennon JC, Bradshaw CM, Szabadi E. Evidence that the effect of 5-HT2 receptor stimulation on temporal differentiation is not mediated by receptors in the dorsal striatum. Behav Process. 2006;71:258–267. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodbeck DR, Hampton RR, Cheng K. Timing behaviour of blackcapped chickadees (parus atricapillus) Behav Process. 1998;44:183–195. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(98)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV. Dopaminergic mechanisms of interval timing and attention. In: Meck WH, editor. Functional and neural mechanisms of interval timing. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2003. pp. 317–338. [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, Meck WH. Timing for the absence of a stimulus: The gap paradigm reversed. J Exp Psych Anim Behav Process. 2000;26:305–322. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.26.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, Meck WH. Differential effects of methamphetamine and haloperidol on the control of an internal clock. Behav Neurosci. 2002a;116:291–297. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, Meck WH. Abstract Viewer / Itinerary Planner. 2002b. Ibotenic lesions of the hippocampus disrupt attentional control of interval timing. Society for Neuroscience. [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, Meck WH. What makes us tick? Functional and neural mechanisms of interval timing. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:755–765. doi: 10.1038/nrn1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, Meck WH. Interval timing with gaps and distracters: Evaluation of the ambiguity, switch, and time-sharing hypotheses. J Exp Psych Anim Behav Process. 2006a;32:329–338. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.32.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, Meck WH. Time sharing in rats: A peak-interval procedure with gaps and distracters. Behav Process. 2006b;71:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2005.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, Paskalis JPG, Cerutti DT. Time-sharing in pigeons: Independent effects of gap duration, position and discriminability from the timed signal. Behav Process. 2006;71:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, Perera D, Meck WH. Memory for timing visual and auditory signals in albino and pigmented rats. J Exp Psych Anim Behav Process. 2005;31:18–30. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.31.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, Sasaki A, Meck WH. Temporal integration as a function of signal and gap intensity in rats (rattus norvegicus) and pigeons (columba livia) J Comp Psych. 2002;116:381–390. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.116.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza de Vaca S, Brown BL, Hemmes NS. Internal clock and memory processes in animal timing. J Exp Psych Anim Behav Process. 1994;20:184–198. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.20.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania AC. Reinforcement schedules and psychophysical judgements: A study of some temporal properties of behavior. In: Schoenfeld WN, editor. The theory of reinforcement schedules. Appleton-Century-Crofts; New York: 1970. pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Chou YH, Halldin C, Farde L. Occupancy of 5-HT1A receptors by clozapine in the primate brain: A pet study. Psychopharm. 2003;166:234–240. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church RM. The internal clock. In: Hulse SH, Fowler H, Honig WK, editors. Cognitive processes in animal behavior. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1978. pp. 277–310. [Google Scholar]

- Church RM. Properties of an internal clock. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1984;423:566–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1984.tb23459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church RM. A concise introduction to scalar timing theory. In: Meck WH, editor. Functional and neural mechanisms of interval timing. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2003. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Church RM, Deluty MZ. Bisection of temporal intervals. J Exp Psych Anim Behav Process. 1977;3:216–228. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.3.3.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church RM, Meck WH, Gibbon J. Application of scalar timing theory to individual trials. J Exp Psych Anim Behav Process. 1994;20:135–155. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.20.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cilia J, Piper DC, Upton N, Hagan JJ. Clozapine enhances breakpoint in common marmosets responding on a progressive ratio schedule. Psychopharm. 2001;155:135–143. doi: 10.1007/s002130100682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coward DM. General pharmacology of clozapine. Br J Psychiatr Suppl. 1992;17:5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Garza R, 2nd, Madras BK. [3H]pnu-101958, a D4 dopamine receptor probe, accumulates in prefrontal cortex and hippocampus of non-human primate brain. Synapse. 2000;37:232–244. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20000901)37:3<232::AID-SYN7>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew MR, Fairhurst S, Malapani C, Horvitz JC, Balsam PD. Effects of dopamine antagonists on the timing of two intervals. Pharm Biochem Behav. 2003;75:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farde L, Nordstrom AL, Wiesel FA, Pauli S, Halldin C, Sedvall G. Positron emission tomographic analysis of central D1 and D2 dopamine receptor occupancy in patients treated with classical neuroleptics and clozapine. Relation to extrapyramidal side effects. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1992;49:538–544. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820070032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin C. Attentional time-sharing in interval timing. In: Meck WH, editor. Functional and neural mechanisms of interval timing. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2003. pp. 235–260. [Google Scholar]

- Fortin C, Masse N. Expecting a break in time estimation: Attentional time-sharing without concurrent processing. J Exp Psych Hum Percept Perform. 2000;26:1788–1796. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.26.6.1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraisse P. Psychologie du temps. Paris, France: P.U.F; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Francois M. Contributions a l'etude du sens du temps: La temperature interne comme facteur de varuation de l'appreciation subjective des durees. Annee Psychologique. 1927;27:186–204. [Google Scholar]

- Gallistel CR, Gelman R. Preverbal and verbal counting and computation. Cognition. 1992;44:43–74. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(92)90050-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon J. Scalar expectancy theory and weber's law in animal timing. Psych Rev. 1977;84:279–325. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon J, Church RM. Time left: Linear versus logarithmic subjective time. J Exp Psych Anim Behav Process. 1981;7:87–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon J, Church RM, Meck WH. Scalar timing in memory. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1984;423:52–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1984.tb23417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon J, Malapani C, Dale CL, Gallistel CR. Toward a neurobiology of temporal cognition: Advances and challenges. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7:170–184. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertel P, Fagerquist MV, Svensson TH. Enhanced cortical dopamine output and antipsychotic-like effects of raclopride by alpha2 adrenoceptor blockade. Science. 1999;286:105–107. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5437.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagland H. The psychological control of judgements of duration: Evidence for a chemical clock. J Gen Psychol. 1933;9:267–287. [Google Scholar]

- Houkal JJ, Buhusi M, Schachner M, Maness P, Buhusi CV. Impaired memory for time in mice lacking the CHL1 cell adhesion molecule; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Eastern Psychological Association; Boston, M.A.. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa J, Ishii H, Bonaccorso S, Fowler WL, O'Laughlin IA, Meltzer HY. 5-HT2A and D2 receptor blockade increases cortical da release via 5-HT1A receptor activation: A possible mechanism of atypical antipsychotic-induced cortical dopamine release. J Neurochem. 2001;76:1521–1531. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser DH, Zentall TR, Neiman E. Timing in pigeons: Effects of the similarity between intertrial interval and gap in a timing signal. J Exp Psych Anim Behav Process. 2002;28:416–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King DJ, Waddington JL. Antipsychotic drugs and the treatment of schizophrenia. In: King DJ, editor. Seminars in psychopharmacology. Gaskell; London: 2004. pp. 316–380. [Google Scholar]

- Kusumi I, Matsubara S, Takahashi Y, Ishikane T, Koyama T. Characterization of [3H]clozapine binding sites in rat brain. J Neural Transm Gen Sect. 1995;101:51–64. doi: 10.1007/BF01271545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leysen JE. Receptor profiles of antipsychotics. In: Ellenbrook BA, Cools AR, editors. Atypical antipsychotics. Birkhauser; Basel: 2000. pp. 57–81. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald CJ, Meck WH. Differential effects of clozapine and haloperidol on interval timing in the supraseconds range. Psychopharm. 2005;182:232–244. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maricq AV, Church RM. The differential effects of haloperidol and methamphetamine on time estimation in the rat. Psychopharm. 1983;79:10–15. doi: 10.1007/BF00433008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maricq AV, Roberts S, Church RM. Methamphetamine and time estimation. J Exp Psych Anim Behav Process. 1981;7:18–30. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.7.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt DW. An algorithm for least squares estimation of parameters. J Soc Ind Appl Math. 1963;11:431–441. [Google Scholar]

- Matell MS, King GR, Meck WH. Differential modulation of clock speed by the administration of intermittent versus continuous cocaine. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118:150–156. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matell MS, Meck WH. Neuropsychological mechanisms of interval timing behavior. Bioessays. 2000;22:94–103. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200001)22:1<94::AID-BIES14>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matell MS, Meck WH. Corticostriatal circuits and interval timing: Coincidence detection of oscillatory processes. Cog Brain Res. 2004;21:139–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matell MS, Meck WH, Nicolelis MA. Interval timing and the encoding of signal duration by ensembles of cortical and striatal neurons. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:760–773. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.4.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH. Neuropharmacology of timing and time perception. Cog Brain Res. 1996;3:227–242. doi: 10.1016/0926-6410(96)00009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH. Neuropsychology of timing and time perception. Brain Cogn. 2005;58:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH. Frontal cortex lesions eliminate the clock speed effect of dopaminergic drugs on interval timing. Brain Res. 2006a;1108:157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH. Neuroanatomical localization of an internal clock: A functional link between mesolimbic, nigrostriatal, and mesocortical dopaminergic systems. Brain Res. 2006b;1109:93–107. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH, Church RM. A mode control model of counting and timing processes. J Exp Psych Anim Behav Process. 1983;9:320–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH, Church RM. Simultaneous temporal processing. J Exp Psych Anim Behav Process. 1984;10:1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH, Church RM. Cholinergic modulation of the content of temporal memory. Behav Neurosci. 1987a;101:457–464. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.101.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH, Church RM. Nutrients that modify the speed of internal clock and memory storage processes. Behav Neurosci. 1987b;101:465–475. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.101.4.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH, Church RM, Gibbon J. Temporal integration in duration and number discrimination. J Exp Psych Anim Behav Process. 1985;11:591–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH, Church RM, Olton DS. Hippocampus, time, and memory. Behav Neurosci. 1984;98:3–22. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.98.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH, Church RM, Wenk GL, Olton DS. Nucleus basalis magnocellularis and medial septal area lesions differentially impair temporal memory. J Neurosci. 1987;7:3505–3511. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-11-03505.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MED-Associates. WMPC software, version 1.15 [computer software] St Albans, VT: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer HY. The role of serotonin in antipsychotic drug action. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:106S–115S. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer HY, Li Z, Kaneda Y, Ichikawa J. Serotonin receptors: Their key role in drugs to treat schizophrenia. Progr Neuropsychopharm Biol Psychiatr. 2003;27:1159–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer HY, Matsubara S, Lee JC. The ratios of serotonin2 and dopamine2 affinities differentiate atypical and typical antipsychotic drugs. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1989;25:390–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobini S, Chiang TJ, Ho MY, Bradshaw CM, Szabadi E. Comparison of the effects of clozapine, haloperidol, chlorpromazine and d-amphetamine on performance on a time-constrained progressive ratio schedule and on locomotor behaviour in the rat. Psychopharm. 2000;152:47–54. doi: 10.1007/s002130000486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olton DS, Meck WH, Church RM. Separation of hippocampal and amygdaloid involvement in temporal memory dysfunctions. Brain Res. 1987;404:180–188. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91369-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olton DS, Wenk GL, Church RM, Meck WH. Attention and the frontal cortex as examined by simultaneous temporal processing. Neuropsychologia. 1988;26:307–318. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(88)90083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rick JH, Horvitz JC, Balsam PD. Dopamine receptor blockade and extinction differentially affect behavioral variability. Behav Neurosci. 2006;120:488–492. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.2.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S. Isolation of an internal clock. J Exp Psych Anim Behav Process. 1981;7:242–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S, Church RM. Control of an internal clock. J Exp Psych Anim Behav Process. 1978;4:318–337. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts WA, Cheng K, Cohen JS. Timing light and tone signals in pigeons. J Exp Psych Anim Behav Process. 1989;15:23–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollema H, Lu Y, Schmidt AW, Zorn SH. Clozapine increases dopamine release in prefrontal cortex by 5-HT1A receptor activation. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;338:R3–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)81951-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherburne LM, Zentall TR, Kaiser DH. Timing in pigeons: The choose-short effect may result from a confusion between delay and intertrial intervals. Psychon Bull Rev. 1998;5:516–522. [Google Scholar]

- Tarazi FI, Campbell A, Yeghiayan SK, Baldessarini RJ. Localization of dopamine receptor subtypes in corpus striatum and nucleus accumbens septi of rat brain: Comparison of D1-, D2-, and D4-like receptors. Neuroscience. 1998;83:169–176. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00386-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treisman M. Temporal discrimination and the indifference interval. Implications for a model of the "Internal clock". Psych Monogr. 1963;77:1–31. doi: 10.1037/h0093864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wearden JH. "Beyond the fields we know": Exploring and developing scalar timing theory. Behav Process. 1999;45:3–21. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(99)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wearden JH. Origines et développement des théories d'horloge interne du temps psychologique. Psychologie Francaise. 2005;50:7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Woodrow H. The reproduction of temporal intervals. J Exp Psych. 1930;13:473–499. [Google Scholar]

- Xiberas X, Martinot JL, Mallet L, Artiges E, Loc HC, Maziere B, Paillere-Martinot ML. Extrastriatal and striatal D2 dopamine receptor blockade with haloperidol or new antipsychotic drugs in patients with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatr. 2001;179:503–508. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.6.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]