Abstract

Clinical allergic airway disease is associated with persistent airway hyperreactivity and remodeling, but little is known about the mechanisms leading to these alterations. This paucity of information is related in part to the absence of chronic models of allergic airway disease. Herein we describe a model of persistent airway hyperreactivity, goblet cell hyperplasia, and subepithelial fibrosis that is initiated by the intratracheal introduction of Aspergillus fumigatus spores or conidia into the airways of mice previously sensitized to A. fumigatus. Similar persistent airway alterations were not observed in nonsensitized mice challenged with A. fumigatus conidia alone. A. fumigatus-sensitized mice exhibited significantly enhanced airway hyperresponsiveness to a methacholine challenge that was still present at 30 days after the conidia challenge. Eosinophils and lymphocytes were present in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples from A. fumigatus-sensitized mice at all times after conidia challenge. Compared with levels measured in A. fumigatus-sensitized mice immediately before conidia, significantly elevated interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and transforming growth factor (TGF-β) levels were present in whole lung homogenates up to 7 days after the conidia challenge. At day 30 after conidia challenge, significantly elevated levels of interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-13 were present in the A. fumigatus-sensitized mice. Histological analysis revealed profound goblet cell hyperplasia and airway fibrosis at days 30 after conidia, and the latter finding was confirmed by hydroxyproline measurements. Thus the introduction of A. fumigatus conidia into A. fumigatus-sensitized mice results in persistent airway hyperresponsiveness, fibrosis, and goblet cell hyperplasia.

Clinical allergic airway diseases, including bronchial asthma, are associated with persistent functional and structural changes within the airways that include airway hyperresponsiveness, increased mucus production, and subepithelial fibrosis. 1,2 Allergic airway inflammation is characterized by the increased presence of eosinophils, lymphocytes, and mast cells. Mediators released by these cells and structural cells around the airway play a major role in airway hyperresponsiveness to exogenous agonists. 3 Changes in the hyperresponsiveness of asthmatic airways are also related to the hyperplasia and hypertrophy of bronchial smooth muscle, concomitant with the occlusion of the airways by plugs of cellular exudate and mucus. Increased mucus secretion in the allergic airways is the consequence of increased numbers of mucus or goblet cells because of hyperplastic and metaplastic events in these specialized cells. 4 Interstitial collagen build-up beneath the airway basement membrane and the fibrotic process results from fibroblast 5 or modified smooth muscle cell 6 activation rather than bronchial epithelial cell dysfunction. The contribution of the airway remodeling response to the severity of asthma remains controversial because increased goblet cell number 7 and collagen deposition 8 around the airways do not appear to reflect the severity of this disease. However, other clinical studies have demonstrated that bronchial subepithelial fibrosis correlates with augmented airway hyperresponsiveness to methacholine. 9 In addition, airway remodeling, particularly around the smaller airways, is a serious consequence of asthma that leads to air flow obstruction 10 and irreversible airway obstruction in up to 80% of elderly patients. 11

Although it is widely recognized that more research is required to identify therapeutic strategies that prevent airway remodeling during allergic airway disease, simple reproducible animal models that recapitulate chronic changes in the airways are lacking. Several models of allergen-specific airway eosinophilia and altered airway physiology have previously been described. 12-14 Unfortunately, the majority of existing models lack persistent airway hyperresponsiveness, mucus cell hyperplasia, and peribronchial fibrotic changes typical of long-term clinical disease. In the present study, we describe a murine model of Aspergillus fumigatus allergen-induced airway disease that exhibits airway hyperresponsiveness, goblet cell hyperplasia, and airway fibrosis. A. fumigatus was the allergen of choice in this chronic model of allergic airway disease. Clinical hypersensitivity responses to A. fumigatus, commonly referred to as allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), can be characterized by asthma-like responses, bronchiectasis, eosinophilia, mucus hypersecretion, and pulmonary fibrosis. 15,16 A detailed description of the airway structural changes and the lung cytokine profile associated with this chronic model of allergic airway disease are provided in the present study. Finally, the development of a chronic model allows for the further evaluation of inflammatory mediators that are involved in the chronic stage of allergic airway disease and for the testing of specific therapeutics.

Materials and Methods

A Novel Model of Chronic Allergic Airway Disease

Specific-pathogen free (SPF) female CBA/J mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were maintained in a SPF facility for the duration of this study. Prior approval for mouse usage in the development of the ABPA model described herein was obtained from the University Laboratory Animal Medicine facility at the University of Michigan Medical School. Sensitization of mice to a commercially available preparation of soluble A. fumigatus antigens was performed as previously described in detail. 17 Briefly, mice received an intraperitoneal and subcutaneous injection of soluble A. fumigatus antigens dissolved in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant. Two weeks after systemic sensitization, each mouse then received a weekly intranasal challenge with A. fumigatus antigen to localize the allergic responsiveness to the airways. One week after the third intranasal challenge, each mouse then received 5.0 × 106 A. fumigatus conidia suspended in 30 μl of 0.1% Tween-80 via the intratracheal route. Nonsensitized mice received normal saline alone via the same routes and over the same time periods, and received the same number of conidia. Sensitized and non-sensitized mice were anesthetized with Vetamine (ketamine hydrochloride, 100 mg/kg i.p.; Mallinckrodt Veterinary, Mundelein, IL) before the intratracheal challenge with conidia. This dose of A. fumigatus conidia has previously been shown to be nonlethal in normal mice. 18 A. fumigatus strain 13073 was cultured as described elsewhere. 19 Conidia obtained from these cultures were suspended in a solution containing 0.1% Tween-80 solution and quantified by particle counter (Z2 particle analyzer; Coulter, Hialeah, FL.).

Determination of Systemic IgE

Sera from A. fumigatus-sensitized and nonsensitized mice were analyzed for total IgE at various times before and after conidia challenge. Complementary capture and detection antibody pairs for mouse IgE were purchased from PharMingen (San Diego, CA), and the IgE enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed according to the manufacturer’s directions. Duplicate sera samples were diluted to 1:100, IgE levels in each were calculated from optical density readings at 492 nm, and IgE concentrations were calculated from a standard curve generated using recombinant IgE (5–2000 pg/ml).

Measurement of Bronchial Hyperresponsiveness

Immediately before and at days 3, 7, and 30 after the intratracheal A. fumigatus conidia challenge, bronchial hyperresponsiveness in A. fumigatus-sensitized and nonsensitized mice was assessed in a Buxco plethysmograph (Buxco, Troy, NY). 20 Sodium pentobarbital (40 mg/kg i.p.; Butler Co., Columbus, OH) was used to anesthetize mice before their intubation for ventilation with a Harvard pump ventilator (Harvard Apparatus, Reno, NV). The following ventilation parameters were used: tidal volume = 0.25 ml, breathing frequency = 120/minutes, and positive end-expiratory pressure ≅ 3 cm H2O. Within the sealed plethysmograph mouse chamber, transpulmonary pressure (ie, Δ tracheal pressure −Δ mouse chamber pressure) and inspiratory volume or flow were continuously monitored online by an adjacent computer. Airway resistance was calculated online via computer software (Buxco) and was determined by the division of the transpulmonary pressure by the change in inspiratory volume. After a baseline period in the Buxco apparatus, anesthetized and intubated mice received a dose of 10 μg of methacholine by tail vein injection, and airway responsiveness to this nonselective bronchoconstrictor was again calculated online. Because nonsensitized mice typically exhibited a little change in airway resistance after a 10-μg methacholine challenge, this dose of methacholine was subsequently used to reveal changes in airway hyperresponsiveness in both conidia models. At the conclusion of the assessment of airway responsiveness each mouse was killed by exsanguination, and a bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed with 1 ml of normal saline. Approximately 500 μl of blood was also collected from each mouse and transferred to a microcentrifuge tube. Sera were obtained after the sample was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 minutes. Whole lungs were finally dissected from each mouse and snap frozen in liquid N2 or prepared for histological analysis.

Morphometric Analysis of Leukocyte Accumulation in BAL Samples

Neutrophils, macrophages, eosinophils, and lymphocytes were quantified in BAL samples applied to coded microscope slides with a cytospin (Shandon Scientific, Runcorn, UK). Identification of each cell type in the cytospins was facilitated by Wright-Giemsa differential stain, and the average number of each cell type was determined in 15 high-powered fields (HPF) (×1000) on every slide.

Cytokine ELISA Analysis

Murine interleukin-18 (IL-18), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), IL-10, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 protein levels were determined in 50 μl of whole lung homogenates, using a standardized sandwich ELISA technique previously described in detail. 21 Whole lungs were homogenized in 2 ml of normal saline containing 2 mg of protease inhibitor (Complete; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) with a Tissue Tearor. Nunc-immuno ELISA plates (MaxiSorp) were coated with the appropriate capture antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at a dilution of 1–5 μg/ml of coating buffer (in mol/L: 0.6 NaCl; 0.26 H3BO4; 0.08 NaOH; pH 9.6) overnight at 4°C. The unbound capture antibody was washed away and each plate was blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin—phosphate-buffered saline (BSA-PBS) for 90 minutes at 37°C. Each ELISA plate was then washed with PBS tween 20 (0.05%; v/v), and 50 μl of undiluted or diluted 1:10 whole lung homogenate was added to duplicate wells and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. After the incubation period, the ELISA plates were then thoroughly washed and the appropriate biotinylated polyclonal rabbit antibody (3.5 μg/ml) was added. After the plates were washed 30 minutes later, streptavidin-peroxidase (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA) was added to each well for 30 minutes, and then they were thoroughly washed again. Chromagen substrate (Bio-Rad Laboratories) was added and optical readings at 492 nm were obtained with an ELISA plate scanner. Recombinant murine cytokines were used to generate the standard curves from which the concentrations present in the samples were derived. The limit of ELISA detection for each cytokine was consistently above 50 pg/ml. Each ELISA was screened to ensure the specificity of each antibody used.

Whole Lung Histological Analysis

Whole lungs from nonsensitized and A. fumigatus-sensitized mice before and after A. fumigatus conidia challenge were fully inflated by the intratracheal perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde. Lungs were then dissected and placed in fresh paraformaldehyde for 24 hours. Routine histological techniques were used to paraffin-embed this tissue, and 5-μm sections of whole lung were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, Masson trichrome, periodic acid Schiff (PAS), and Gomori methanamine silver (GMS). Inflammatory infiltrates and other histological changes were examined around bronchioles and larger airways, using light microscopy because the eosinophilic inflammation was exclusively associated with these pulmonary structures. Eosinophils were counted at high magnification (×1000), using a multiple-step analysis of whole lung histological sections mounted on coded slides. A minimum of 20 airways was analyzed on each slide, and data were expressed as the average number of airway-associated eosinophils per HPF.

Hydroxyproline Assay

Total lung collagen levels were determined using a previously described assay. 22 Briefly, a 500-μl sample of lung homogenate (see above) was subsequently added to 1 ml of 6 N HCl for 8 hours at 120°C. To a 5-μl sample of the digested lung, 5 μl of citrate/acetate buffer (5% citric acid, 7.2% sodium acetate, 3.4% sodium hydroxide, and 1.2% glacial acetic acid, pH 6.0) and 100 μl of chloramine-T solution (282 mg chloramine-T, 2 ml of n-propanol, 2 ml of distilled water, and 16 ml of citrate/acetate buffer) were added. The resulting samples was then incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes before 100 μl of Ehrlich’s solution (Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI), was added. These samples were incubated for 15 minutes at 65°C, and cooled samples were read at 550 nm in a Beckman DU 640 spectrophotometer. Hydroxyproline concentrations were calculated from a standard curve of hydroxyproline (zero to 100 μg/ml).

Data Statistical Analysis

All results are expressed as mean ± SEM (SE). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons were used to determine statistical significance in both groups at various times after the conidia challenge; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Intratracheal Conidia Challenge in Nonsensitized and A. fumigatus-Sensitized Mice Did Not Precipitate Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis

Invasive aspergillosis is commonly observed in immunodeficient patients, 23 and this disease can be reproduced in mice rendered neutropenic with cyclophosphamide treatment and then challenged intratracheally with A. fumigatus conidia. 19 In the present study, GMS-stained histological sections of whole lung from nonsensitized and A. fumigatus-sensitized mice did not show any evidence of hyphae or invasive growth at any time after conidia challenge. In addition, A. fumigatus could not be cultured from BAL samples removed from either group at 3, 7, and 30 days after conidia challenge (not shown). These findings suggested that allergic airway disease induced in nonsensitized and A. fumigatus-sensitized mice was not associated with fungal colonization or invasive disease after conidia challenge.

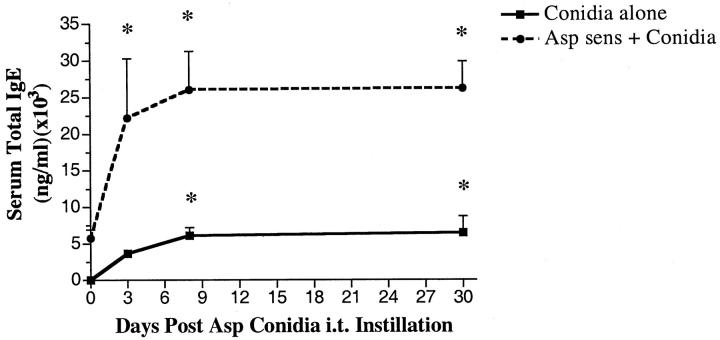

Profoundly Increased Serum IgE in A. fumigatus-Sensitized Mice Challenged Intratracheally with Conidia

Increased IgE is a hallmark of hypersensitivity to A. fumigatus, 23,24 and IgE levels fluctuate with ABPA severity. 25,26 Measurement of serum IgE levels in the present study revealed a marked difference in the generation of IgE by the two groups after their challenge with A. fumigatus conidia (Figure 1) ▶ . As expected, mice previously sensitized to A. fumigatus had approximately 5250 ± 500 ng/ml of IgE immediately before conidia challenge, whereas total IgE levels were below the level of detection in the nonsensitized group. In both groups, peak IgE levels were measured at day 7 after conidia, but approximately fivefold greater levels of IgE were evident in the A. fumigatus-sensitized mice compared with the nonsensitized group (Figure 1) ▶ . In both groups, the levels of total IgE remained significantly elevated above baseline levels at day 30 after conidia. Thus these results suggested that the introduction of A. fumigatus conidia into sensitized mice greatly augmented the IgE response to this fungus.

Figure 1.

Serum IgE levels in nonsensitized and A. fumigatus-sensitized mice before and at various times after A. fumigatus conidia challenge. Total IgE was measured using a specific ELISA as described in the Materials and Methods section. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 5/group/time point. * denotes P ≤ 0.05 compared with values measured in both groups before the conidia challenge.

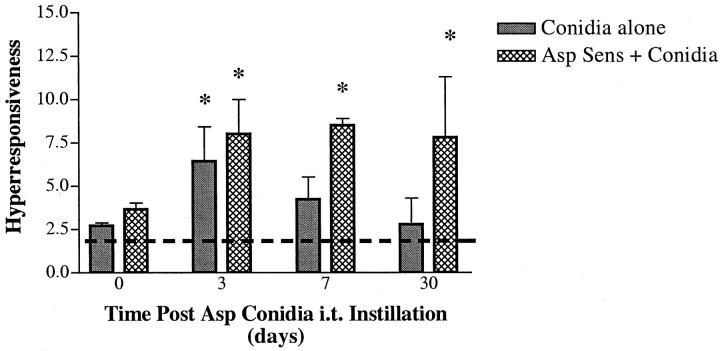

Airway Hyperresponsiveness Is Present in A. fumigatus-Sensitized Mice Intratracheally Challenged 30 Days Previously with Conidia

We have previously examined airway hyperresponsiveness in mice that were sensitized with soluble A. fumigatus antigens and observed that airway physiology had returned to normal by day 3 after an intratracheal challenge with soluble A. fumigatus. 17 In the present study, our objective was to obtain a model in which airway physiology changes persisted for a much longer time. Accordingly, airway physiology was monitored immediately before and at various days after the intratracheal challenge of nonsensitized and A. fumigatus-sensitized mice with A. fumigatus conidia. Before conidia, the two groups of mice exhibited similar changes in airway resistance (units = cm H2O/ml/second) after intravenous methacholine provocation (Figure 2) ▶ . However, neither group showed airway responses at this time that were significantly increased above the baseline airway resistance measured in the absence of methacholine (Figure 2 ▶ ; the dashed line is the baseline response for both groups of mice). At day 3 after conidia, airway hyperresponsiveness was significantly increased threefold above the baseline in the nonsensitized group, whereas airway resistance was increased fourfold above the baseline in the A. fumigatus-sensitized group. At days 7 and 30 after conidia, significantly increased airway responsiveness to methacholine was present only in mice previously sensitized to A. fumigatus (Figure 2) ▶ . Thus these results demonstrated that persistent airway hyperresponsiveness is a consequence of conidia challenge in mice previously sensitized to A. fumigatus and that chronic changes to airway physiology can occur in a murine model of allergic airway disease.

Figure 2.

Airway hyperresponsiveness in nonsensitized and A. fumigatus-sensitized mice before and at various times after A. fumigatus conidia challenge. Changes in airway resistance or hyperresponsiveness (units = cm H2O/ml/second) were monitored at each time point by the intravenous injection of methacholine. The dashed line indicates the airway resistance measured in both groups in the absence of methacholine (ie, baseline resistance). Values are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 5/group/time point. * denotes P ≤ 0.05 compared with the baseline airway resistance.

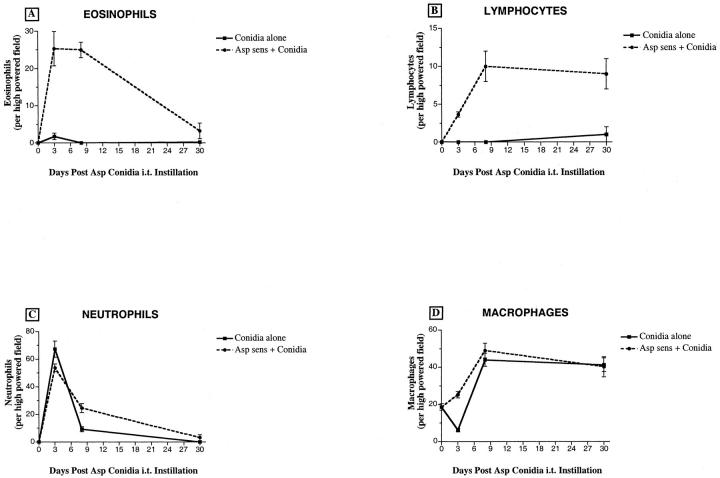

Eosinophils and Lymphocytes Are Present in BAL Samples from A. fumigatus-Sensitized Mice Intratracheally Challenged 30 Days Previously with Conidia

We next examined leukocyte populations within BAL samples before and after conidia challenge, and major differences in eosinophil and lymphocyte numbers were apparent between the two groups of mice described here. BAL samples from mice previously sensitized to A. fumigatus contained 25 ± 5 and 25 ± 2 eosinophils per high-powered field (HPF) at days 3 and 7, respectively, after conidia challenge (Figure 3A) ▶ . At day 30 after conidia, eosinophils (4 ± 2 per HPF) were still present in BAL samples from the sensitized group. The greatest number of lymphocytes was detected at day 7 after conidia challenge (10 ± 3 per HPF), and lymphocyte counts remained significantly elevated at day 30 after conidia challenge (9 ± 3 per HPF) (Figure 3B) ▶ . In contrast, minor increases in eosinophil and lymphocyte numbers were observed in BAL samples from nonsensitized mice that received conidia alone (Figures 3, A and B ▶ , respectively). Overall, the changes in neutrophils and macrophage counts in the BAL were similar in the two conidia groups (Figures 3, C and D ▶ , respectively). Neutrophil and macrophage counts in the BAL were significantly elevated at days 3 and 7, respectively, after conidia in both groups of mice (Figure 3) ▶ . Thus these data suggested that the pulmonary inflammatory response to conidia differed greatly between the two groups of mice. This difference was most aptly illustrated by the markedly increased movement of eosinophils and lymphocytes into the BAL compartment during the conidia challenge.

Figure 3.

Leukocyte counts in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples from nonsensitized and A. fumigatus-sensitized mice before and at various times after A. fumigatus conidia challenge. BAL cells were dispersed onto microscope slides using a cytospin, and eosinophils, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages were differentially stained with Wright-Giemsa stain. Twenty-five high-powered fields were examined in each cytospin. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 25 hpf/time point.

Cytokine Levels in Whole Lung Homogenates are Markedly Altered in A. fumigatus-Sensitized Mice Intratracheally Challenged with Conidia

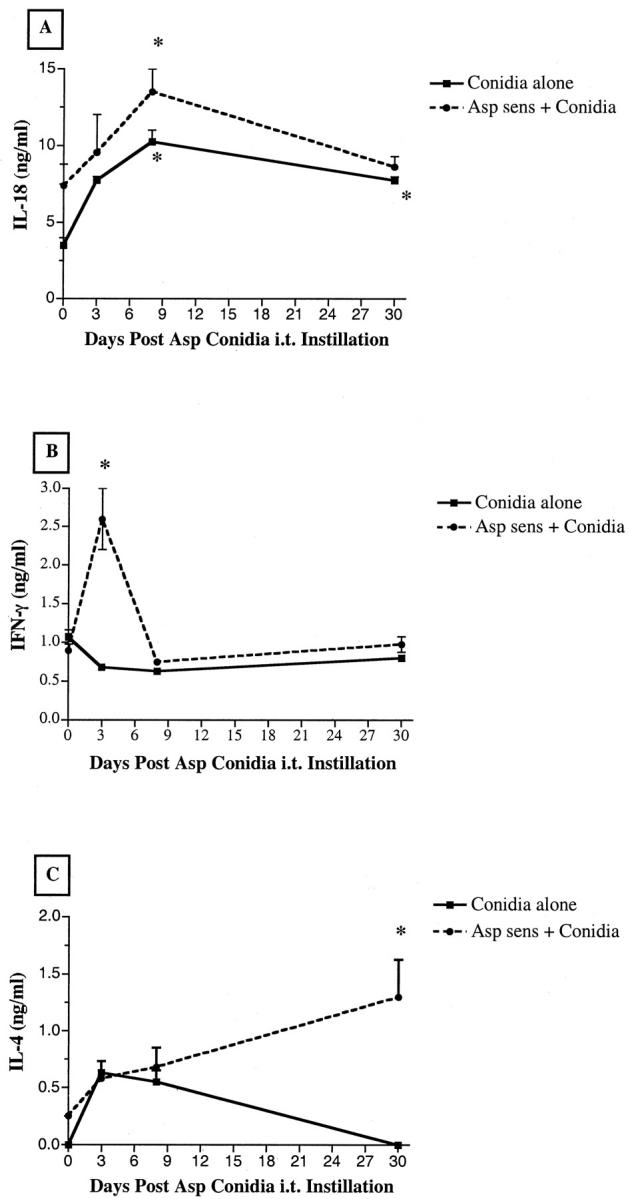

The intratracheal introduction of soluble A. fumigatus antigens into mice increases the synthesis of Th2- and Th1-type cytokines within the lung. 27 More recently, Grunig and colleagues 28 have shown that IL-10 is a natural modulator of inflammatory Th2-type as well as Th1-type responses during experimental ABPA. Figure 4,A and B ▶ , illustrates the changes in two common examples of Th1-type cytokines, namely IL-18 and IFN-γ, measured before (ie, baseline levels) and after conidia challenge in nonsensitized and A. fumigatus-sensitized mice. Baseline IL-18 levels in whole lung samples were significantly higher in the sensitized group compared with the nonsensitized group (Figure 4A) ▶ . After the conidia challenge, the two groups of mice showed similar significant elevations in IL-18. Furthermore, IL-18 remained significantly elevated above baseline levels in the nonsensitized group at day 30 after conidia. IFN-γ levels were similar in the two groups before the conidia challenge, but whole lung samples from the sensitized group contained significantly greater IFN-γ at day 3 after conidia challenge compared with the baseline levels (Figure 4B) ▶ . At the later time points, IFN-γ levels in both groups were not different from baseline levels. Also depicted in Figure 4 ▶ are changes in the Th2-type cytokine IL-4 (panel C). Baseline levels of IL-4 cytokines in whole lung homogenates were elevated in the sensitized group compared with the nonsensitized group. Whole lung levels of IL-4 were similar in the two groups at days 3 and 7 after conidia. However, IL-4 levels were significantly greater in the sensitized group compared with the nonsensitized group at day 30 after conidia.

Figure 4.

IL-18 (A), IFN-γ (B), and IL-4 (C) levels in whole lung homogenates from nonsensitized and A. fumigatus-sensitized mice before and at various times after A. fumigatus conidia challenge. Cytokine levels were measured using a specific ELISA as described in the Materials and Methods section. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 5 mice/group/time point. * denotes P ≤ 0.05 compared with values measured in both groups before the conidia challenge.

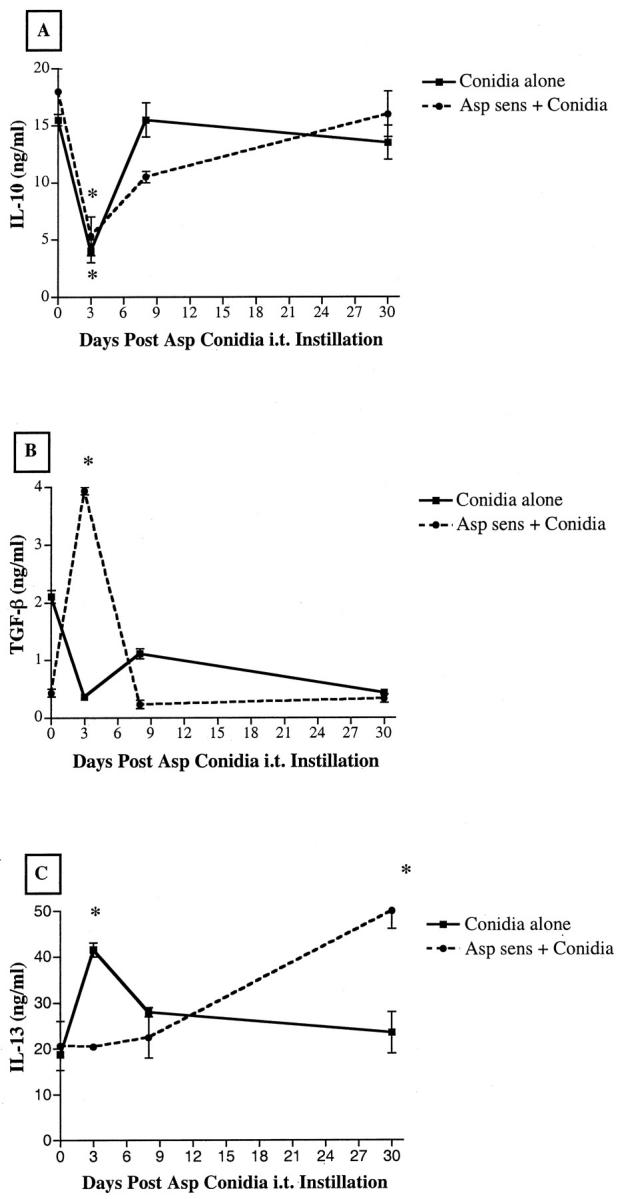

Figure 5 ▶ depicts whole lung levels of IL-10, TGF-β, and IL-13 before and after conidia challenge. Whole lung IL-10 levels were similar in the two groups before conidia and both showed similar significant decreases in IL-10 at day 3 after conidia (Figure 5A) ▶ . At day 30, IL-10 levels in both groups were similar to baseline levels. In contrast, TGF-β and IL-13 showed divergent patterns of expression in the two conidia groups both before and after conidia challenge. Before conidia challenge, TGF-β levels were increased significantly by fourfold in the nonsensitized group compared with the sensitized group. At day 3 after conidia, the levels of TGF-β were significantly increased eightfold in the A. fumigatus-sensitized group but decreased by fourfold in the nonsensitized group (Figure 5B) ▶ . The two conidia groups had similar levels of TGF-β at day 30 after conidia. IL-13 levels in lung homogenates were similar in the two groups before conidia. At day 3 after conidia, IL-13 levels in the nonsensitized group were significantly increased twofold above baseline levels. In contrast, significantly more IL-13 was detected only at day 30 after conidia challenge in the A. fumigatus-sensitized group. Thus major differences in the magnitude and timing of cytokine production were detected in whole lung homogenates from nonsensitized and A. fumigatus-sensitized mice after conidia challenge.

Figure 5.

IL-10 (A), TGF-β (B), and IL-13 (C) levels in whole lung homogenates from nonsensitized and A. fumigatus-sensitized mice before and at various times after A. fumigatus conidia challenge. Cytokine levels were measured using a specific ELISA as described in the Materials and Methods section. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 5 mice/group/time point. * denotes P ≤ 0.05 compared with values measured in both groups before the conidia challenge.

Severe Eosinophilic Inflammation, Goblet Cell Hyperplasia, and Collagen Deposition in A. fumigatus-Sensitized Mice Intratracheally Challenged 30 Days Previously with Conidia

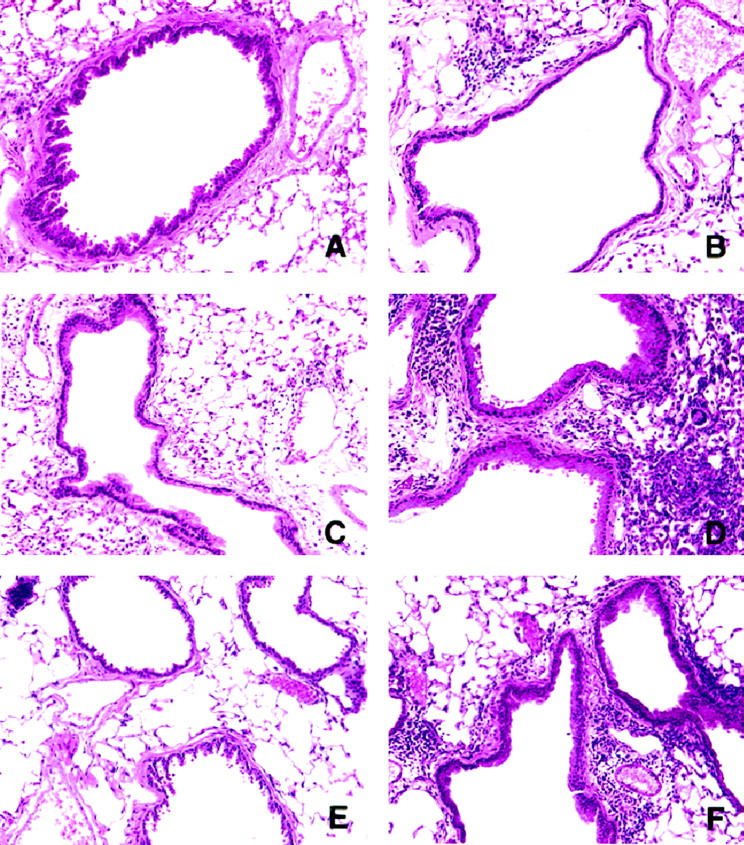

Many of the characteristic histological features of chronic human asthma were present in whole lungs from A. fumigatus-sensitized mice, particularly at the latter times of the conidia challenge period. Conversely, the nonsensitized group challenged with conidia exhibited fewer of these features, and at day 30 whole lungs from this group lacked all of the chronic features of chronic airway disease. As shown in Figure 6 ▶ , although absent from normal mice (A), an eosinophilic infiltrate was present around the airways of A. fumigatus-sensitized mice before the conidia challenge (Figure 6B) ▶ . Eosinophils and lymphocytes were commonly juxtaposed with small and large airways in both groups of mice at day 7 after conidia (Figure 6C) ▶ . However, the eosinophilic and lymphocytic inflammation was of much greater intensity in the sensitized mice at this time. As shown in Figure 6D ▶ , sensitized mice showed profound airway and parenchymal inflammation at day 7 after conidia. At day 30 after conidia, airway inflammation was not observed in the nonsensitized group (Figure 6E) ▶ , but evidence of some airway inflammation was still apparent in sensitized mice at this time (Figure 6F) ▶ .

Figure 6.

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained whole lung sections from nonsensitized and A. fumigatus-sensitized mice before and at various times after A. fumigatus conidia challenge, showing the extent of the eosinophilic and lymphocytic inflammation around small airways. The photomicrographs are representative of lungs removed from nonsensitized mice before conidia (A) and at day 7 (C) and day 30 (E) after conidia. Representative lung sections from A. fumigatus-sensitized mice before conidia (B) and at day 7 (D) and day 30 (F) after conidia are also depicted. Original magnification, ×200.

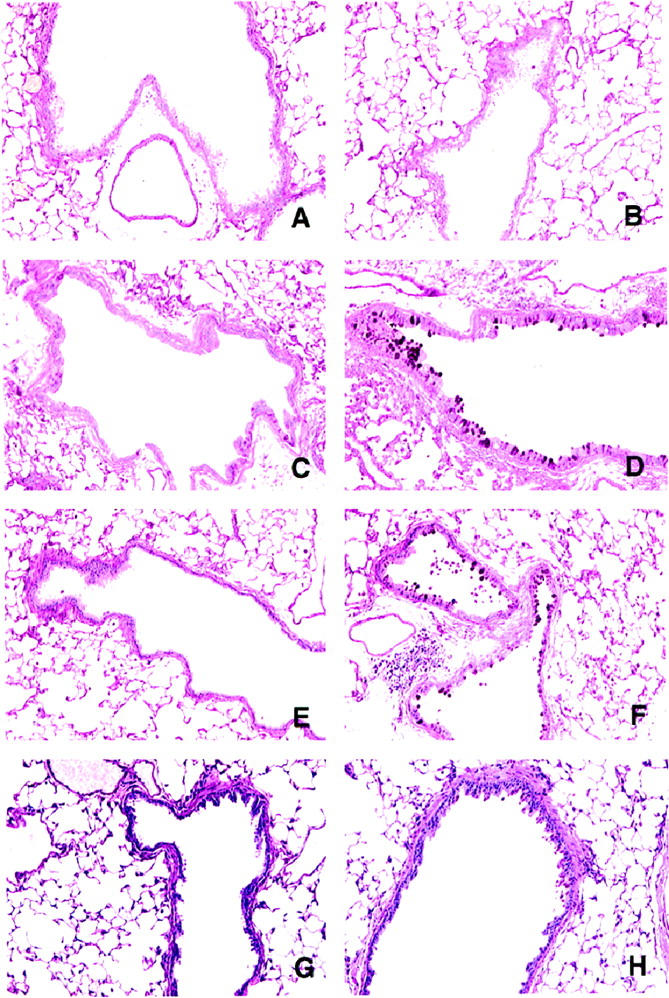

Changes in airway mucus cell numbers in both groups are illustrated in Figure 7 ▶ . Whole lungs from A. fumigatus-sensitized mice stained with PAS showed airway epithelial cell hypertrophy, mucus cell metaplasia, and the hyperproduction of acidic mucus in large and small airways at all times after conidia challenge (Figure 7, D, F, and H) ▶ . Similar increases in mucus cell numbers and hyperproduction of acidic mucus were absent from nonsensitized mice challenged with conidia.

Figure 7.

Periodic acid Schiff (PAS)-stained whole lung sections from nonsensitized and A. fumigatus-sensitized mice before and at various times after A. fumigatus conidia challenge, showing the extent of mucus or goblet cell hyperplasia. The photomicrographs are representative of lungs removed from nonsensitized mice before conidia (A) and at day 3 (C), day 7 (E), and day 30 (G) after conidia. B depicts representative PAS staining in the airways of A. fumigatus-sensitized mice before conidia. Goblet cells stained dark magenta were readily apparent in whole lung sections from A. fumigatus-sensitized mice at day 3 (D), day 7 (F), and day 30 (H) after conidia. Original magnification, ×200.

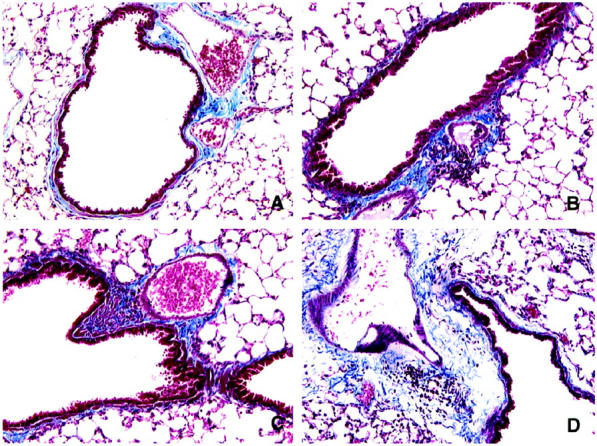

Masson trichrome staining was used to reveal the subepithelial deposition of collagen in both conidia groups (Figure 8) ▶ . Collagen staining was similar in the two groups before the conidia challenge (Figure 8, A and B) ▶ . At day 30 after conidia, collagen staining did not appear to be markedly increased above baseline in the nonsensitized group. Nevertheless, at the same time after conidia, the Masson trichrome staining revealed a marked increase in collagen surrounding the airways of the A. fumigatus-sensitized group. Thus the intratracheal introduction of conidia into A. fumigatus-sensitized mice markedly altered the pulmonary architecture.

Figure 8.

Masson trichrome-stained whole lung sections from nonsensitized and A. fumigatus-sensitized mice before and at various times after A. fumigatus conidia challenge, showing the extent of collagen deposition (light blue material) around small airways and adjacent blood vessels. The photomicrographs are representative of lungs removed from nonsensitized mice before conidia (A) and at day 30 (C) after conidia and A. fumigatus-sensitized mice before conidia (B) and at day 30 (D) after conidia. Markedly greater amounts of collagen were apparent around airways from sensitized mice challenged with conidia. Original magnification, ×200.

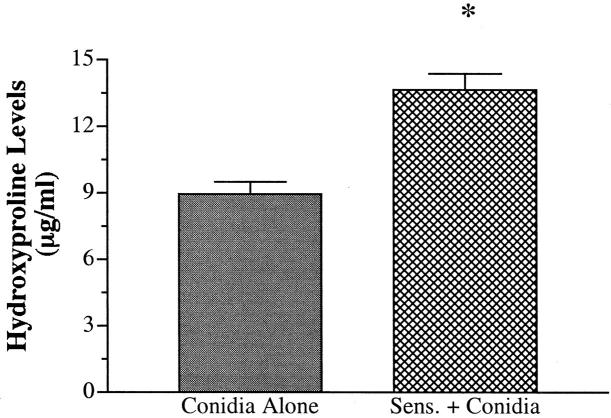

Hydroxyproline Levels Are Significantly Increased in A. fumigatus-Sensitized Mice Intratracheally Challenged 30 Days Previously with Conidia

The changes in Masson trichrome staining described above suggested that the airways of A. fumigatus-sensitized mice were surrounded with markedly greater amounts of collagen at day 30 after conidia. To confirm these histological findings, total hydroxyproline was measured in whole lung samples removed from both groups before and at 30 days after conidia challenge. Approximately 2 μg/ml of hydroxyproline was present in whole lung samples from both groups before conidia challenge. At day 30 after conidia, both groups showed significantly greater levels of hydroxyproline compared with their respective baseline levels before conidia challenge (Figure 9) ▶ . However, hydroxyproline levels were significantly greater in the sensitized group compared with the nonsensitized group at this time. Thus these findings confirm that the introduction of conidia into A. fumigatus-sensitized mice was associated with a marked enhancement in hydroxyproline levels and supported the histological evidence that these mice exhibited much greater subepithelial fibrosis.

Figure 9.

Hydroxyproline levels in whole lung homogenates from nonsensitized and A. fumigatus-sensitized mice at day 30 after A. fumigatus conidia challenge. Hydroxyproline levels were measured as described in the Materials and Methods section. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 5/group/time point. * denotes P ≤ 0.05 compared with the values measured in the nonsensitized group.

Discussion

Complex inflammatory and repair processes create the phenotype that characterizes asthma and other allergic airway diseases. 29 Allergic airways are often occluded by cellular exudates and mucus, exhibit epithelial and goblet cell hyperplasia, 4 and are surrounded by copious amounts of newly deposited extracellular matrix. Eosinophils and lymphocytes are commonly found in close apposition to remodeled airways, suggesting that these cells or the mediators they release may contribute to these alterations. 30 Furthermore, infiltrating T cells have been shown to be responsible for airway hyperresponsiveness, allergic inflammation, and goblet cell hyperplasia but not IgE reactivity in an acute murine model of allergic airway disease. 31 However, the mechanisms responsible for persistent airway changes during allergic airway disease are poorly characterized because investigation has been hampered by the lack of a simple animal model that exhibits these features of this disease. Although chronic models of allergic airway disease have previously been described, these models are labor intensive because of the requirement for several allergen challenges over extended periods of time. 13

In the present study, chronic airway changes were observed in mice sensitized to soluble A. fumigatus antigens (using a standardized sensitization protocol) 12 and then given one intratracheal challenge with 5 × 106A. fumigatus conidia. The airway changes included airway hyperresponsiveness, mucus cell hyperplasia, and peribronchial fibrosis, and all of these features of chronic allergic airway disease were evident at day 30 after conidia challenge. Interestingly, these features were not present in nonsensitized mice at day 30 after conidia. We also examined the cytokine profile associated with both conidia groups and observed that the inflammatory response in the sensitized group was characterized by significant increases in IFN-γ, IL-4, TGF-β, and IL-13. Thus we have developed a chronic model of allergic airway disease that will allow for subsequent studies directed at defining the precise role of various soluble cytokine mediators during airway remodeling.

Increasing evidence points to a major immunomodulatory role for cytokines in allergic airway disease. Th2 cells are often isolated from asthmatic subjects, leading to the speculation that these cells exert a major role in asthma, but experimental data show that Th2-mediated allergic lung inflammation is also associated with a vigorous Th1-mediated response. 32 Furthermore, Grunig and colleagues 28 have shown that IL-10 regulates both Th responses during A. fumigatus-induced allergic airway disease. In the present study, we examined the changes in Th1-type (ie, IL-18 and IFN-γ) cytokines and IL-10 in whole lung homogenates from nonsensitized and A. fumigatus-sensitized mice at various times before and after the A. fumigatus conidia challenge. No previous studies have addressed the role of IL-18 in experimental allergic responses to A. fumigatus, but IFN-γ is elevated during clinical ABPA. 33 Elevations in IFN-γ are probably of great significance in the model of chronic airway inflammation described here because IFN-γ has been shown to prime alveolar macrophages during allergic reactions to release inflammatory cytokines. 34 Given that IL-10 has a major suppressive role during allergic airway responses to A. fumigatus, 28 it was interesting to note that whole lung IL-10 levels were significantly inhibited in both groups at day 3 after conidia. There is no explanation for this decrease at present, but it may be related to clinical findings showing that alveolar macrophages have an increased capacity to release proinflammatory cytokines and a reduced capacity to produce IL-10 during asthma. 35 Thus both conidia models were associated with changes in Th1-type cytokines and IL-10, particularly during the early stages after conidia challenge.

TGF-β, IL-4, and IL-13 are cytokines of particular interest because of their potential role in the chronic airway changes observed in sensitized mice challenged with conidia. TGF-β is a potent profibrotic cytokine that is greatly increased around asthmatic airways and is largely localized to infiltrating eosinophils. 2 IL-13 partly utilizes components of the IL-4 receptor signaling pathway for MCP-1 generation by endothelial cells 36 and β1-integrin and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) expression and MCP-1 generation by fibroblasts. 37 Furthermore, the targeted pulmonary expression of IL-13 elicits an inflammatory response, goblet hyperplasia, subepithelial fibrosis, de novo cytokine synthesis, airway obstruction, and hyperresponsiveness. 38 Thus the changes in whole lung levels of profibrotic and inflammatory cytokines such as TGF-β and IL-13 presumably contribute to the chronic airway changes in A. fumigatus-sensitized mice after conidia challenge.

In conclusion, we have developed a chronic model of allergic airway disease that will permit a detailed examination of the mechanisms that lead to persistent airway hyperresponsiveness, goblet cell hyperplasia, and peribronchial fibrosis. In particular, further investigations are planned to address the role of cytokines in the chronic airway changes associated with this model.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Cory M. Hogaboam, Department of Pathology, University of Michigan Medical School, 1301 Catherine Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-0602. E-mail: hogaboam@path.med.umich.edu.

Supported by an American Lung Association Research grant (CMH) and National Institutes of Health grants HL35276 (SLK), HL31963 (SLK), and AI36302 (SLK).

References

- 1.Roberts CR: Is asthma a fibrotic disease? Chest 1995, 107(Suppl 3):111S-117S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minshall EM, Leung DY, Martin RJ, Song YL, Cameron L, Ernst P, Hamid Q: Eosinophil-associated TGF-β1 mRNA expression, and airways fibrosis in bronchial asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1997, 17:326-333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boulet LP, Chakir J, Dube J, Laprise C, Boutet M, Laviolette M: Airway inflammation and structural changes in airway hyper-responsiveness and asthma: an overview. Can Respir J 1998, 5:16-21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jany B, Basbaum CB: Mucin in disease. Modification of mucin gene expression in airway disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991, 144:S38-S41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roche WR, Beasley R, Williams JH, Holgate ST: Subepithelial fibrosis in the bronchi of asthmatics. Lancet 1989, 1:520-524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halayko AJ, Stephens NL: Potential role for phenotypic modulation of bronchial smooth muscle cells in chronic asthma. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 1994, 72:1448-1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lundgren JD, Vestbo J: The pathophysiological role of mucus production in inflammatory airway diseases. Respir Med 1995, 89:315-316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu HW, Halliday JL, Martin RJ, Leung DY, Szefler SJ, Wenzel SE: Collagen deposition in large airways may not differentiate severe asthma from milder forms of the disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998, 158:1936-1944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boulet LP, Laviolette M, Turcotte H, Cartier A, Dugas M, Malo JL, Boutet M: Bronchial subepithelial fibrosis correlates with airway responsiveness to methacholine. Chest 1997, 112:45-52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoshino M, Nakamura Y, Sim J, Shimojo J, Isogai S: Bronchial subepithelial fibrosis and expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in asthmatic airway inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1998, 102:783-788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reed CE: The natural history of asthma in adults: the problem of irreversibility. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999, 103:539-547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell EM, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM, Lukacs NW: Temporal role of chemokines in a murine model of cockroach allergen-induced airway hyperreactivity and eosinophilia. J Immunol 1998, 161:7047-7053 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Temelkovski J, Hogan SP, Shepherd DP, Foster PS, Kumar RK: An improved murine model of asthma: selective airway inflammation, epithelial lesions and increased methacholine responsiveness following chronic exposure to aerosolized allergen. Thorax 1998, 53:849-856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blyth DI, Pedrick MS, Savage TJ, Hessel EM, Fattah D: Lung inflammation and epithelial changes in a murine model of atopic asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1996, 14:425-438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richeson RBd, Stander PE: Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. An increasingly common disorder among asthmatic patients. Postgrad Med 1990, 88:217–219, 222, 224 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Elstad MR: Aspergillosis and lung defenses. Semin Respir Infect 1991, 6:27-36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hogaboam C, Gallinat C, Taub D, Strieter R, Kunkel S, Lukacs N: Immunomodulatory role of C10 chemokine in a murine model of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. J Immunol 1999, 162:6071-6079 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao JL, Wynn TA, Chang Y, Lee EJ, Broxmeyer HE, Cooper S, Tiffany HL, Westphal H, Kwon-Chung J, Murphy PM: Impaired host defense, hematopoiesis, granulomatous inflammation and type 1-type 2 cytokine balance in mice lacking CC chemokine receptor 1. J Exp Med 1997, 185:1959-1968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehrad B, Strieter RM, Standiford TJ: Role of TNFalpha in pulmonary host defense in murine invasive aspergillosis. J Immunol 1999, 162:1633-1640 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lukacs NW, Strieter RM, Warmington K, Lincoln P, Chensue SW, Kunkel SL: Differential recruitment of leukocyte populations and alteration of airway hyperreactivity by C-C family chemokines in allergic airway inflammation. J Immunol 1997, 158:4398-4404 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evanoff H, Burdick MD, Moore SA, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM: A sensitive ELISA for the detection of human monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1). Immunol Invest 1992, 21:39-49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keane MP, Belperio JA, Moore TA, Moore BB, Arenberg DA, Smith RE, Burdick MD, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM: Neutralization of the CXC chemokine, macrophage inflammatory protein-2, attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. J Immunol 1999, 162:5511-5518 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cockrill BA, Hales CA: Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Annu Rev Med 1999, 50:303-316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murali PS, Kurup VP, Bansal NK, Fink JN, Greenberger PA: IgE down regulation, and cytokine induction by Aspergillus antigens in human allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. J Lab Clin Med 1998, 131:228-235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patterson R, Greenberger PA, Lee TM, Liotta JL, O’Neill EA, Roberts M, Sommers H: Prolonged evaluation of patients with corticosteroid-dependent asthma stage of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1987, 80:663-668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knutsen AP, Mueller KR, Hutcheson PS, Slavin RG: Serum anti-Aspergillus fumigatus antibodies by immunoblot and ELISA in cystic fibrosis with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1994, 93:926-931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurup VP, Seymour BWP, Choi H, Coffman RL: Particulate Aspergillus fumigatus antigens elicit a Th2 response in BALB/c mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1994, 93:1013-1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grunig G, Corry DB, Leach MW, Seymour BW, Kurup VP, Rennick DM: Interleukin-10 is a natural suppressor of cytokine production and inflammation in a murine model of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. J Exp Med 1997, 185:1089-1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holgate ST: Asthma: a dynamic disease of inflammation and repair. Ciba Found Symp 1997, 206:5-28-34, 106110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeffery PK: Histological features of the airways in asthma and COPD. Respiration 1992, 59(Suppl 1):13-16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corry DB, Grunig G, Hadeiba H, Kurup VP, Warnock ML, Sheppard D, Rennick DM, Locksley RM: Requirements for allergen-induced airway hyperreactivity in T and B cell-deficient mice. Mol Med 1998, 4:344-355 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li L, Xia Y, Nguyen A, Feng L, Lo D: Th2-induced eotaxin expression and eosinophilia coexist with Th1 responses at the effector stage of lung inflammation. J Immunol 1998, 161:3128-3135 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker C, Bauer W, Braun RK, Menz G, Braun P, Schwarz F, Hansel TT, Villiger B: Activated T cells and cytokines in bronchoalveolar lavages from patients with various lung diseases associated with eosinophilia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994, 150:1038-1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dery RE, Bissonnette EY: IFN-γ potentiates the release of TNF-α, and MIP-1α by alveolar macrophages during allergic reactions. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1999, 20:407-412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.John M, Lim S, Seybold J, Jose P, Robichaud A, O’Connor B, Barnes PJ, Chung KF: Inhaled corticosteroids increase interleukin-10 but reduce macrophage inflammatory protein-1α, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and interferon-γ release from alveolar macrophages in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998, 157:256-262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goebeler M, Schnarr B, Toksoy A, Kunz M, Brocker EB, Duschl A, Gillitzer R: Interleukin-13 selectively induces monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 synthesis and secretion by human endothelial cells. Involvement of IL-4R α and Stat6 phosphorylation. Immunology 1997, 91:450-457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doucet C, Brouty-Boye D, Pottin-Clemenceau C, Canonica GW, Jasmin C, Azzarone B: Interleukin (IL)-4, and IL-13 act on human lung fibroblasts: implications in asthma. J Clin Invest 1998, 101:2129-2139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu Z, Homer RJ, Wang Z, Chen Q, Geba GP, Wang J, Zhang Y, Elias JA: Pulmonary expression of interleukin-13 causes inflammation, mucus hypersecretion, subepithelial fibrosis, physiologic abnormalities, and eotaxin production. J Clin Invest 1999, 103:779-788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]