Abstract

Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) is a γ2-herpesvirus consistently identified in Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), primary effusion lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman’s disease. Although HHV-8 infection appears to be necessary, it may not be sufficient for development of KS without the involvement of other cofactors. One potentially important cofactor is HIV-1. HIV-1-infected cells produce HIV-1-related proteins and cytokines, both of which have been shown to promote growth of KS cells in vitro. Though HIV-1 is not absolutely necessary for KS development, KS is the most frequent neoplasm in AIDS patients, and AIDS-KS is recognized as a particularly aggressive form of the disease. To determine whether HIV-1 could participate in the pathogenesis of KS by modulating HHV-8 replication (rather than by inducing immunodeficiency), HIV-1-infected T cells were cocultured with the HHV-8-infected cell line, BCBL-1. The results demonstrate soluble factors produced by or in response to HIV-1-infected T cells induced HHV-8 replication, as determined by production of lytic phase mRNA transcripts, viral proteins, and detection of progeny virions. By focusing on cytokines produced in the coculture system, several cytokines known to be important in growth and proliferation of KS cells in vitro, particularly Oncostatin M, hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor, and interferon-γ, were found to induce HHV-8 lytic replication when added individually to BCBL-1 cells. These results suggest specific cytokines can play an important role in the initiation and progression of KS through reactivation of HHV-8. Thus, HIV-1 may participate more directly than previously recognized in KS by promoting HHV-8 replication and, hence, increasing local HHV-8 viral load.

Human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8, also known as Kaposi’s sarcoma associated herpesvirus or KSHV) is the first known member of γ2-herpesviruses (genus Rhadinovirus) to infect humans. 1,2 This virus has been consistently associated with Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), primary effusion lymphomas (PEL, also termed body cavity-based lymphomas or BCBL), and multicentric Castleman’s disease. 3 Epidemiological evidence strongly implicates HHV-8 as the etiological agent of KS. This conclusion is based on the presence of HHV-8 in all four clinical forms of KS and in virtually all KS lesions, 4-7 the presence of HHV-8-specific antibodies in a majority of KS patients (over 80%), but a minor proportion of normal healthy blood donors (<10%), 8-11 and the presence of HHV-8-specific antibodies in patients before the development of KS lesions. 10

All herpesviruses, including HHV-8, share the ability to establish latent infections in their natural host cells. 12 In latent infection, the viral genome persists extrachromosomally as a circular episome, viral gene expression is severely restricted, and viral progeny are not produced. 13 Previous studies have demonstrated that HHV-8 viral replication in PEL and KS tumor cells is tightly regulated, with the virus being held predominantly in a latent state. 14,15 However, treatment of PEL cells with either phorbol esters (TPA) or n-butyrate induces HHV-8 reactivation. During reactivation, HHV-8-infected cells express a variety of lytic cycle genes and produce viral progeny, which ultimately results in the destruction of the host cell. 16-19 Regulation of viral replication is critical to disease progression as the proportion of virally infected cells undergoing lytic replication increases, so does the degree of tissue damage and progression of the infection. Indeed, studies have shown that HHV-8 viral load is higher in KS patients than in HHV-8-infected individuals without KS, and HHV-8 viral load also increases during progression of KS to the late (nodular) stage of the disease. 13,20,21

Although HIV-1 infection is neither necessary nor sufficient for the development of KS, AIDS-KS is known to be more aggressive, disseminated, and resistant to treatment than other forms of KS, including forms also associated with immunosuppression. 22-24 Immunosuppression clearly plays a role in the development of KS, but immunosuppression alone cannot explain the overwhelming prevalence of KS in AIDS patients (relative risk of developing KS in AIDS patients is 70-fold higher than in immunosuppressed transplant patients), 25,26 the frequent presentation of KS in the early stages of AIDS before the onset of severe immunosuppression, 27,28 and the overwhelming association of KS in patients infected with HIV-1 but not HIV-2. 29 Recent studies by Ariyoshi et al demonstrate that KS developed almost exclusively in HIV-1-positive, not HIV-2-positive, patients in Gambia, West Africa, despite essentially equivalent seroprevalance for HHV-8 and severity of immunosuppression in both groups. 29

In an attempt to explain the more aggressive nature of KS in HIV-1-positive patients, HHV-8 replication was examined in the persistently infected PEL cell line, BCBL-1, after coculture with an HIV-1-infected CD4+ T cell line. The results demonstrate that soluble factors produced by HIV-1-infected CEM cells induce lytic cycle replication of HHV-8. In the present study, we focused on inflammatory cytokines and found that cytokines important in the growth and proliferation of KS tumor cells in vitro, particularly Oncostatin M (OSM), hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (HGF/SF), and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), induce HHV-8 lytic cycle replication. Previous studies from our group and others have demonstrated the presence of HIV-1 in KS skin lesions in proximity to the cells that harbor HHV-8. These studies identified HIV-1 transcripts in dermal dendritic cells, T cells, and basal keratinocytes in KS. 30,31 Similarly, HHV-8 was identified in basal keratinocytes, eccrine epithelial cells, KS tumor cells, and endothelial cells. 32,33 In addition, recent studies have found that dendritic cells, keratinocytes, and macrophages can also be infected by HHV-8 in vitro. 34-36 Therefore, we propose that the HIV-1-mediated enhancement of HHV-8 lytic replication may increase the local viral load and, hence, increase the likelihood of tumor formation. Such a mechanism would point to a more direct relationship between HIV-1 and HHV-8 than previously postulated by other investigators studying KS.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Viral Infection

CEM-SS cells (kindly provided by Drs. Clive Woffendin and Gary Nabel, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI) were maintained in RPMI-1640 (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mmol/L glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (RPMI + 10% FBS). The BCBL-1 cell line, originally isolated by Drs. Michael McGrath and Don Ganem, was obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. 18 BCBL-1 cells, an EBV-negative and HHV-8-positive PEL cell line, were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% FBS, 5% normal human AB serum (BioWhittaker) and 2 mmol/L L-glutamine (BCBL-1 media) at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere. BC-1 cells (an HHV-8- and EBV-positive PEL cell line) and BC-3 cells (an EBV-negative and HHV-8-positive PEL cell line) were obtained from ATCC and were grown in RPMI + 10% FBS or RPMI + 20% FBS, respectively. 37 For experiments using normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), human whole blood was separated on a Ficoll-Hypaque gradient and PBMCs isolated from the interface. The cells were washed three times in RPMI 1640 and resuspended in RPMI + 10% FBS containing 20 U/ml interleukin-2 (IL-2) before infection with HIV-1.

In a majority of the coculture experiments, Transwell dishes (CoStar) were used to prevent cell-cell interactions while allowing passage of soluble factors, such as cytokines and viral particles, between the two cultures. Several experiments required supplementation of the culture media with recombinant cytokines. The cytokines used were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) and included IFN-γ (50–1000 U/ml), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α; 1000 U/ml), IL-6 (50 ng/ml), HGF/SF (100 ng/ml), OSM (10 ng/ml), and IL-2 (20 U/ml).

High-titer stocks of HIV-1IIIB (kindly provided by Drs. Clive Woffendin and Gary Nabel) and HIV-1SF2 (AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases) were prepared by passaging the viruses on CEM cells. The TCID50 titer (106/ml) was calculated as terminal dilution producing syncytia. CEM cells were incubated with 0.01 multiplicity of infection of HIV-1 for 4 hours at 37°C. After the incubation, cells were washed with RPMI-1640 and resuspended at 3 × 10 5 cells/ml in RPMI + 10% FBS. Production of HIV-1 was monitored by measuring reverse transcriptase (RT) activity in tissue culture supernatants (performed in duplicate) as previously described. 38

Northern Blot Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cells using a phenol/ guanidine isothiocyanate/chloroform-based technique (Trizol, Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Twelve micrograms of total RNA was fractionated on a 1% agarose formaldehyde gel and transferred to a nylon membrane (Zetabind, Cuno Inc., Meriden, CT). Even loading of RNA and efficiency of transfer was confirmed by staining of the 18S and 28S bands on the membrane with methylene blue. 39 The blot was prehybridized with Church’s hybridization buffer and probed with a [32P]-labeled dCTP probes generated using gel-purified PCR products and a random prime label kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN). The blots were washed with sodium phosphate buffers containing sodium dodecyl sulfate, EDTA, and bovine serum albumin and exposed to Kodak film.

Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

cDNA was synthesized from isolated RNA using the SuperScript Preamplication system for First Strand cDNA Synthesis (Gibco BRL) following the manufacturer’s instructions. To ensure no DNA contamination of the RNA, which could lead to false positive results, the RNA samples were treated with DNase I (Gibco BRL) before reverse transcription. As an additional control, each sample was also subjected to reverse transcription in the absence of RT. Single-stranded cDNA was then amplified using standard PCR techniques as previously described. 40,41 Primers used for analysis included HHV-8 ORF26 primers originally described by Chang et al 1 and HGF/SF (5′-TTT GCC TTC GAG CTA TCG GG-3′, 5′-GAA TTT GTG CCG GTG TGG TG-3′). To prevent PCR contamination due to previously amplified PCR products, all PCR reactions were set up in a separate location from the area used for amplification and analysis. All PCR-related reagents were stored in this room, including dedicated pipettors, aerosol barrier pipette tips, and reaction tubes. Uracil DNA glycosylase and dUTP-spiked dNTP were also used in the PCR reaction to destroy any previously amplified product, as previously described. 42,43

Immunoperoxidase Staining

Cytospin preparations of cultured cells were fixed for 10 minutes in 50:50 acetone:methanol and air-dried. The cells were immunostained to detect a variety of antigens using a highly sensitive avidin-biotin immunoperoxidase technique (Vectastain kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) as previously described. 44 The chromogen, 3-amino-4-ethylcarbazole was used, producing a positive red reaction. The panel of monoclonal antibodies (mAb) used included CD4 (mouse IgG; Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA), HHV-8 ORF 59 (clone 11D1, mouse IgG), and HHV-8 ORF K8.1 A/B (clone 2A3, mouse IgG). Both ORF 59 and K8.1 mAbs recognize HHV-8 lytic cycle proteins and have been previously described. 45-47 To calculate the percentage of positive cells, photographs of at least 10 unique fields were taken of every slide, and the number of positive and negative cells counted separately by two individuals, including one who was blinded to the results. Immunostaining was performed on samples from three separate experiments.

Ribonuclease Protection Assay (RPA)

Expression of mRNA encoding for cytokines was evaluated in BCBL-1, CEM, and HIV-1-infected CEM cells both before and after coculture using RPA kits and the manufacturer’s recommended instructions (RiboQuant RPA kit, Pharmingen, San Diego, CA).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Production of IFN-γ, OSM, and HGF/SF was measured in PBMC, PBMC + HIV, CEM, CEM + HIV, and BCBL-1 cells both before and after coculture using Quantikine ELISA kits (R&D Systems). The assay was performed as recommended by the manufacturer using undiluted tissue culture supernatants. Each sample was run in duplicate and the assay repeated a minimum of two times.

Electron Microscopy (EM)

BCBL-1 cells were stimulated for 7 days with HGF/SF as described. The cells were collected, washed once with PBS, and fixed with EM-grade glutaraldehyde in cacodylate buffer. Cells were processed, sectioned, and stained by the Loyola University Core Imaging facility. Analysis and interpretation of electron micrographs was performed by an expert electron microscopist, Dr. Raoul Fresco (Loyola University, Maywood, IL).

Results

Coculture of BCBL-1 Cells with HIV-1IIIB-Infected CEM Cells Results in Induction of HHV-8 Replication

To test the hypothesis that HIV-1 may play a role in regulation of HHV-8 replication, BCBL-1 cells were cultured in direct contact with HIV-1IIIB infected CEM cells (CEM + HIV-1IIIB). Northern blot analysis for T0.7 mRNA at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours after coculture demonstrated an increase in HHV-8 mRNA (data not shown). Expression of T0.7 mRNA increased over time in the cocultured cells, in comparison with untreated BCBL-1 (twofold increase at 24 hours, rising to a sixfold increase at 96 hours). Analysis of mRNA for the cellular “housekeeping” gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) on the same membrane indicated that loading of RNA was similar (data not shown).

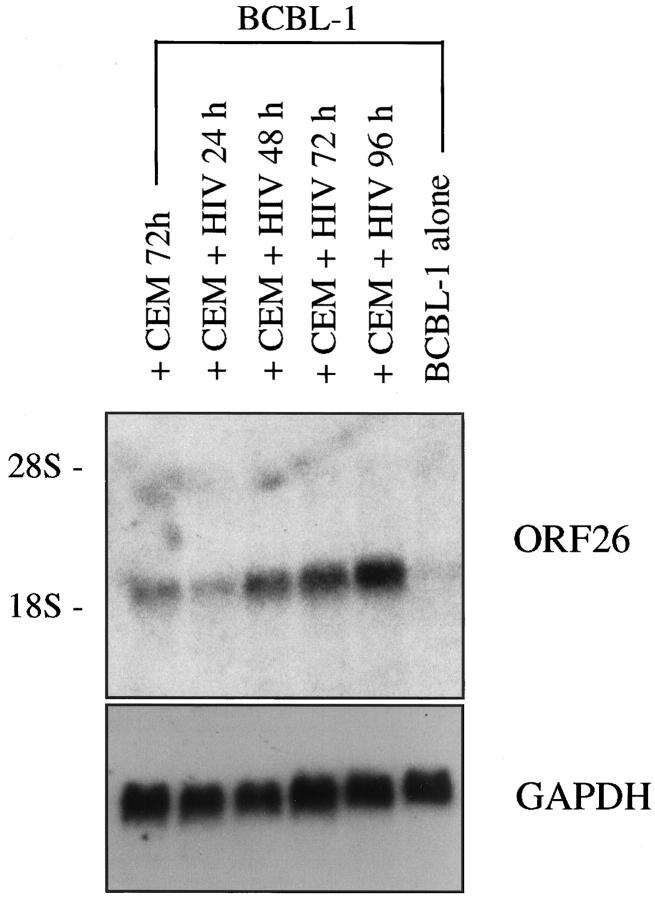

As the factor(s) responsible for increased HHV-8 replication may be either soluble or cell-associated, similar coculture experiments were performed in Transwell dishes to prevent direct contact between the two cell types. Northern blot analysis for ORF26 mRNA (expressed only during lytic HHV-8 replication) demonstrated an increase in mRNA expression, which continued to increase over time (Figure 1) ▶ . Of interest, ORF26 mRNA also increased after coculture with uninfected CEM cells, but to a lesser extent than demonstrated with CEM+HIV-1IIIB at the same time point (Figure 1) ▶ . Analysis of data from 5 independent experiments demonstrated that, on average, ORF26 expression was increased 2.6 ± 0.39-fold at 72 hours and 3.25 ± 0.44-fold at 96 hours when comparing BCBL-1 cells cocultured with uninfected versus HIV-infected CEM cells. In each experiment, analysis of GAPDH on the same membrane demonstrated loading of RNA was similar. The results indicated not only that soluble factors are responsible for induction of HHV-8, but these factors induce HHV-8 lytic phase replication; not simply a proliferation of latently infected cells.

Figure 1.

Expression of ORF26 mRNA is increased in BCBL-1 cells following coculture with CEM + HIV-1IIIB. BCBL-1 cells were cultured in Transwell dishes with uninfected or HIV-1IIIB-infected CEM cells as indicated. Lane 1, BCBL-1 cells cultured with CEM cells, 72 hours (2.7-fold increase compared to BCBL-1 cells alone); lane 2, BCBL-1 cells cultured with CEM + HIV-1IIIB, 24 hours (1.8-fold increase); lane 3, BCBL-1 cells cultured with CEM + HIV-1IIIB, 48 hours (4.8-fold increase); lane 4, BCBL-1 cells cultured with CEM + HIV-1IIIB, 72 hours (5.5-fold increase); lane 5, BCBL-1 cells cultured with CEM + HIV-1IIIB, 96 hours (7.0-fold increase); lane 6, BCBL-1 cells alone. A representative experiment is shown; seven independent experiments were run with similar results (increased ORF26 mRNA at 96 hours of coculture ranged from 6.0- to 12.9-fold increase).

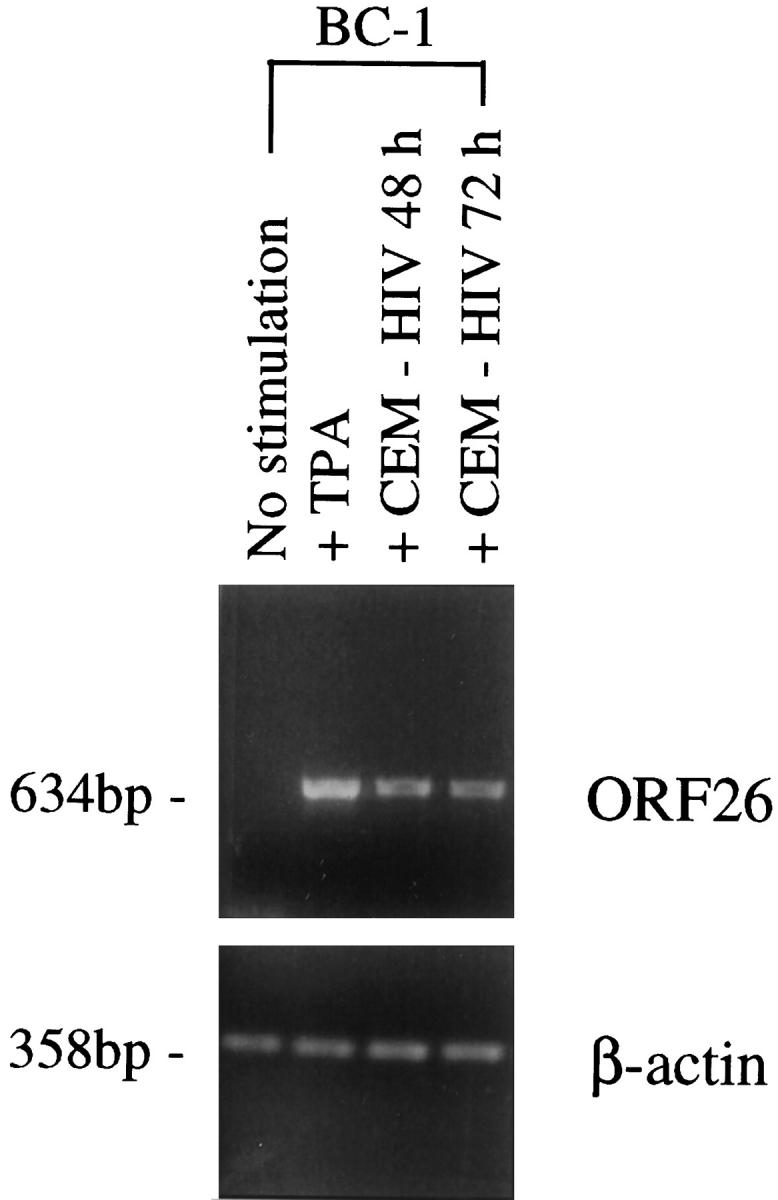

Experiments were also performed with two additional PEL cell lines, BC-1 and BC-3 cells. Results with BC-3 cells (HHV-8-positive, EBV-negative PEL cells) were similar to the BCBL-1 cell line. Northern blot analysis showed increased expression of ORF26 mRNA in BC-3 cells following 96 hours of coculture with CEM cells (1.7-fold increase compared to BC-3 cells alone) or with CEM + HIV (4.3-fold increase, data not shown). BC-1 cells are infected with both HHV-8 and EBV, and replication of HHV-8 is tightly confined to the latent phase. 37 Northern blot analysis demonstrated no detectable expression of ORF26 following coculture with HIV-infected or uninfected CEM cells (data not shown). However, ORF26 was readily identifiable in positive control lanes containing RNA from TPA and/or butyrate stimulated BC-1 cells. As Northern blot analysis is a relatively insensitive method for detection of transcripts expressed at low levels, RT-PCR was performed. Indeed, the results showed ORF26 transcripts were not detected in unstimulated BC-1 cell cultures; however, after coculture with HIV-1 infected CEM cells, ORF26 transcripts were induced (Figure 2) ▶ . The difference in the results between BCBL-1 and BC-1 cells may be due to the expression of EBV-regulatory proteins in BC-1 cells, which may suppress HHV-8 re-activation.

Figure 2.

RT-PCR analysis for ORF26 mRNA expression in BC-1 cells cocultured with CEM + HIV-1IIIB. Transcripts for ORF26 were not detected in unstimulated BC-1 cells, but were induced after coculture with CEM + HIV-1IIIB or TPA stimulation (positive control). β-actin was readily detectable in all samples indicating the presence of amplifiable cDNA, and no bands were seen in control reactions performed in the absence of RT, indicating that the RNA template was not contaminated with DNA (data not shown).

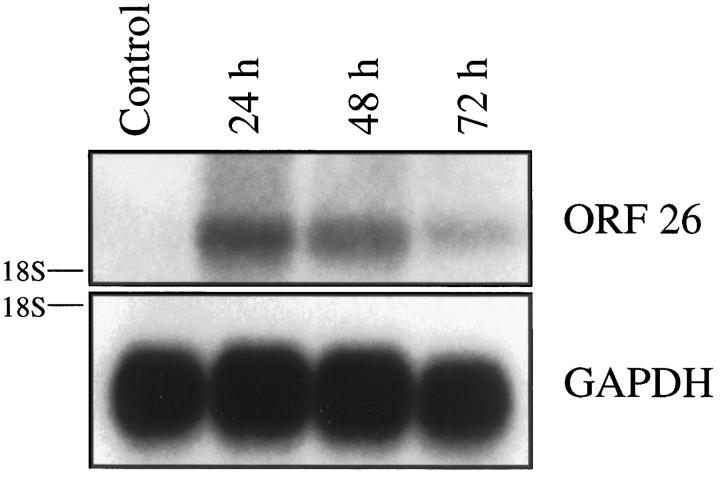

To confirm that soluble factors were responsible for induction of HHV-8 mRNA, conditioned media was collected from a BCBL-1/CEM + HIV-1IIIB coculture experiment at 96 hours, filtered to remove contaminating cells, and added to fresh BCBL-1 cells for a final concentration of 50% conditioned media. Northern blot analysis demonstrated a significant increase in HHV-8 ORF26 mRNA after 24 hours of culture which decreased at both the 48 and 72 hour time points (Figure 3) ▶ . The decrease in HHV-8 ORF26 mRNA likely represented exhaustion of critical factors in the conditioned media over time which are responsible for induction of the HHV-8 lytic cycle.

Figure 3.

Northern blot analysis for ORF26 mRNA in BCBL-1 cells cultured for 24 to 72 hours in 50% conditioned media. ORF26 mRNA was increased following culture of BCBL-1 cells for 24 hours with conditioned media (10.8-fold increase compared with untreated BCBL-1 cells) which decreased at both the 48- and 72-hour time points (7.1-fold and 2.4-fold increase compared to untreated cells, respectively).

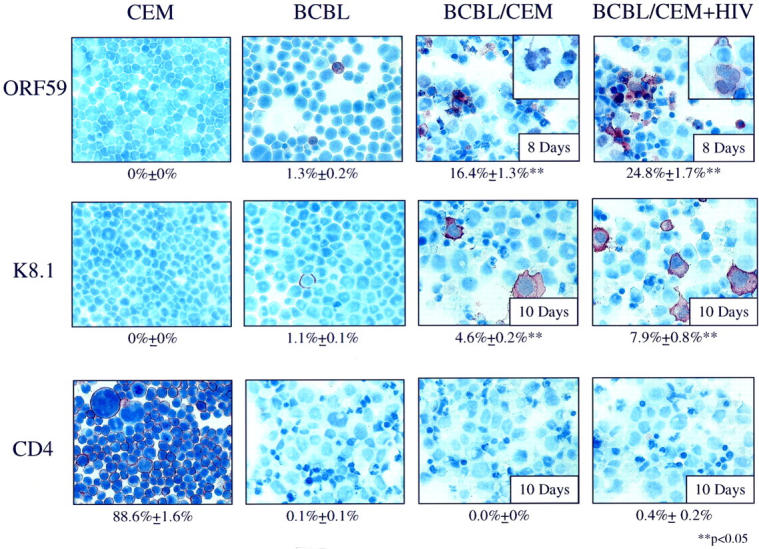

To determine whether induction of HHV-8 lytic cycle RNA also resulted in induction of lytic cycle proteins, immunostaining of BCBL-1 cells to detect two HHV-8 lytic cycle proteins (ORF59 and K8.1) was performed. After 8 days of coculture with CEM + HIV-1IIIB cells in Transwell dishes, 24.8 ± 1.7% of BCBL-1 cells expressed ORF59 compared to 16.4 ± 1.3% of BCBL-1 cells cultured with uninfected CEM cells or 1.3 ± 0.2% of untreated BCBL-1 cells (P < 0.005; Figure 4 ▶ , top row). Of importance, expression of ORF59 has been previously shown to occur earlier and more frequently in the lytic cycle compared with expression of ORF K8.1. 48 Indeed, after 10 days of coculture with CEM + HIV-1IIIB cells, 7.9 ± 0.8% of BCBL-1 cells expressed ORF K8.1 compared to 4.6% ± 0.2% of BCBL-1 cells cultured with uninfected CEM cells and 1.1% ± 0.1% of untreated BCBL-1 cells (P < 0.005, Figure 4 ▶ center row). Staining for an isotype control mAb, CD4, showed less than 0.4 ± 0.2% reactivity with cocultured BCBL-1 cells; however, 88.6 ± 1.6% of CEM cells were positive for CD4 (Figure 4 ▶ , bottom row).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical staining of BCBL-1 cells cocultured in Transwell dishes with CEM or CEM + HIV-1IIIB (original magnification, ×60). Top row (ORF59 mAb): CEM cells (0% positive), untreated BCBL-1 cells (1.3% positive), BCBL-1 cells cultured with uninfected CEM cells for 8 days (16.4% positive), BCBL-1 cells cultured with CEM + HIV-1IIIB for 8 days (24.8% positive). Inset figures are enlarged to show nuclear staining in the indicated samples with ORF59 mAb. Middle row (K8.1 mAb): CEM cells (0% positive), untreated BCBL-1 cells (1.1% positive), BCBL-1 cells cocultured with CEM cells for 10 days (4.6% positive), BCBL-1 cells cocultured with CEM + HIV-1IIIB for 10 days (7.9% positive). Bottom row (CD4 mAb): CEM cells (88.6% positive), untreated BCBL-1 cells (0.1% positive), BCBL-1 cells cocultured with CEM cells cultured for 10 days (0% positive), BCBL-1 cells cocultured with CEM + HIV-1IIIB for 10 days (0.4% positive). Note the low level of nonspecific mAb binding using the isotype-matched control mAb (CD4) in the coculture conditions. **Analysis of variance demonstrates statistically significant increases in K8.1 and/or ORF59 expression compared to untreated BCBL-1 cells.

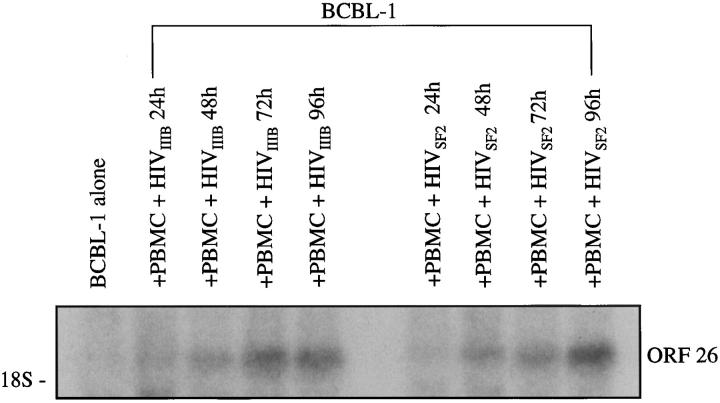

To determine whether the results with the CEM T cell line and HIV-1IIIB (a T cell-tropic HIV strain) could be generalized to other cell types and HIV-1 strains, Transwell coculture experiments were performed with normal human PBMCs infected with either HIV-1IIIB or HIV-1SF2, a monocytotropic strain of HIV. The results demonstrated an up-regulation in ORF26 mRNA expression which increased over time for PBMCs infected with either HIV strain (Figure 5) ▶ .

Figure 5.

Northern blot analysis of ORF26 expression in BCBL-1 cells cocultured with normal human PBMCs infected with HIV-1IIIB or HIV-1SF2. Lane 1: BCBL-1 alone, 72 hours; lane 2, BCBL with PBMC + HIV-1IIIB, 24 hours (1.6-fold increase); lane 3, BCBL with PBMC + HIV-1IIIB, 48 hours (4.2-fold increase); lane 4, BCBL with PBMC + HIV-1IIIB, 72 hours (8.2-fold increase); lane 5, BCBL with PBMC + HIV-1IIIB, 96 hours (8.4-fold increase); lane 6, BCBL with PBMC + HIV-1SF2, 24 hours (1.1-fold increase); lane 7, BCBL with PBMC + HIV-1SF2, 48 hours (4.5-fold increase); lane 8, BCBL with PBMC + HIV-1SF2, 72 hours (6.4-fold increase); lane 9, BCBL with PBMC + HIV-1SF2, 96 hours (12.8-fold increase).

Identification of Soluble Factors Contributing to Induction of HHV-8 Replication: Cytokines

As HHV-8 lytic replication was induced by soluble factors, we reasoned that cytokines released either by CEM, CEM + HIV-1IIIB, or BCBL-1 cells (in response to culture with HIV-1-infected T cells) were likely candidates to mediate this response. To identify cytokines modulated in the coculture system, RPA assays were performed (Table 1) ▶ . Of particular interest, IFN-γ mRNA was not detected in CEM or CEM + HIV-1IIIB cells, but was readily detected in BCBL-1 cells, particularly after coculture with CEM + HIV-1IIIB (10-fold increase at 72 hours of coculture compared to baseline levels). IFN-γ mRNA was also detected in BCBL-1 cells cocultured with uninfected CEM cells, but the increase was significantly less (fivefold increase at 72 hours of coculture) than in the presence of HIV-1. In addition, OSM mRNA was not expressed by BCBL-1 cells in any of the assay conditions, but was detected in CEM and CEM+HIV-1IIIB cells. CEM and CEM+HIV-1IIIB cells cocultured with BCBL-1 cells expressed OSM mRNA at modestly increased levels (25% increase compared to CEM or CEM+HIV-1IIIB alone). As the RPA kits do not evaluate expression of HGF/SF mRNA, RT-PCR was used to evaluate production of this mRNA. Results showed HGF/SF mRNA was not detected in CEM or CEM + HIV, but was readily detected in BCBL-1 cells both before and after coculture with CEM + HIV (data not shown).

Table 1.

Induction of Cytokine mRNA in Cocultured Cells

| Cytokine mRNA | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cells | Not detected | Low to moderate expression | High expression |

| BCBL-1 alone | |||

| TNF-α, TNF-β | TGF-β2, TGF-β3 | TGF-β1 | |

| OSM | IL-1, IL-6, IL-7, IL-9, IL-12 | IL-10 | |

| M-CSF | IFN-γ | ||

| LT-β | G-CSF | ||

| IL-15 | |||

| BCBL-1 coculture with CEM/CEM+ HIV | |||

| OSM | TGF-β2, TGF-β3 | TGF-β1 | |

| M-CSF | TNF-α, TNF-β | IL-10 | |

| IL-15 | IFN-γ | ||

| IL-1, IL-6, IL-7, IL-9, IL-12 | |||

| LT-β | |||

| G-CSF | |||

| CEM alone | |||

| TNF-α | TGF-β2, TGF-β3 | TGF-β1 | |

| IFN-γ | IL-15 | M-CSF | |

| IL-1, IL-6, IL-7 | TNF-β | ||

| IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 | OSM | ||

| G-CSF | LT-β | ||

| CEM cocultured with BCBL-1 | |||

| TNF-α | TGF-β2, TGF-β3 | TGF-β1 | |

| IFN-γ | IL-15 | M-CSF | |

| IL-1, IL-6, IL-7 | TNF-β | ||

| IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 | OSM | ||

| G-CSF | LT-β | ||

| CEM+ HIV | |||

| IFN-γ | TGF-β2, TGF-β3 | TGF-β1 | |

| IL-1, IL-6, IL-7 | TNF-α, TNF-β | M-CSF | |

| IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 | IL-15 | ||

| G-CSF | OSM | ||

| LT-β | |||

| CEM+ HIV cocultured with BCBL-1 | |||

| IFN-γ | TGF-β2, TGF-β3 | TGF-β1 | |

| IL-1, IL-6, IL-7 | TNF-α, TNF-β | M-CSF | |

| IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 | IL-15 | ||

| G-CSF | OSM | ||

| LT-β |

RPA kits were used to detect expression of cytokine-related mRNA in BCBL-1, CEM, and CEM + HIV cells before and after coculture. Densitometry was used to evaluate the intensity of bands for calculation of differences in mRNA expression. After background was subtracted for each lane, densitometry values <100 were considered low/moderate expression and values >100 were considered high expression. “Not detected” indicates that the densitometry value in the area of interest was equal to or less than background, with no evidence of a visible band.

G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; M-CSF, macrophage colony stimulating factor.

ELISA assays were used to confirm and extend the mRNA data. Supernatant samples from cocultures were tested with commercially available ELISA assays for IFN-γ, OSM, and HGF/SF proteins. IFN-γ was not detected in CEM cells, CEM+HIV-1IIIB cells, or BCBL-1 cells, but was produced by BCBL-1 cells cocultured with CEM + HIV-1IIIB. Levels of IFN-γ increased over time starting at undetectable levels at time 0 and reaching 12–20 pg/ml at 8 days of coculture. OSM was not produced by BCBL-1 cells, but was produced by CEM cells, CEM+HIV-1IIIB cells, and CEM or CEM+HIV-1IIIB cells cocultured with BCBL-1 cells. The cells produced approximately 10–14 pg/ml of OSM, and there was no significant difference in expression of OSM between the groups or over time. HGF/SF was not detected in BCBL-1, CEM or CEM + HIV-1IIIB cells. However, following coculture of either CEM or CEM + HIV-1IIIB cells with BCBL-1 cells, HGF/SF could be detected in the culture media. HGF/SF levels were undetectable at early time points and steadily increased over time to 90 ± 47 pg/ml (CEM cocultured with BCBL-1), and 206 ± 45 pg/ml (CEM + HIV cocultured with BCBL-1) after 10 days.

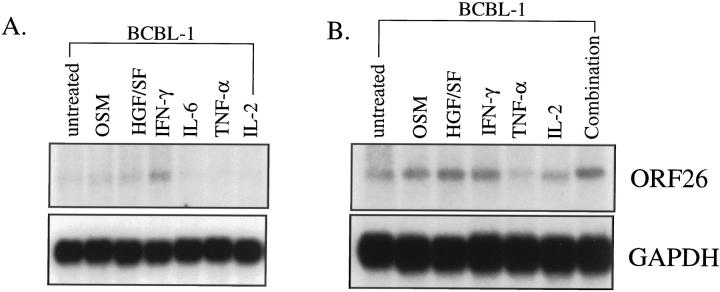

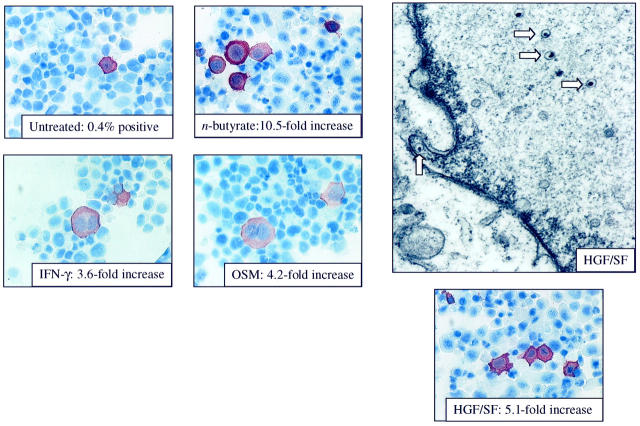

As IFN-γ, OSM, and HGF/SF were all detected at the protein level in pg/ml concentrations, experiments were designed to determine whether recombinant cytokines could also induce HHV-8 lytic replication. BCBL-1 cells were stimulated in culture with recombinant cytokines (IFN-γ, OSM, HGF/SF, IL-6, TNF-α, or IL-2) and HHV-8 replication examined. Using Northern blot analysis, studies demonstrated an increase in ORF26 mRNA in BCBL-1 cells stimulated with OSM, HGF/SF and IFN-γ, but not IL-6, TNF-α, or IL-2 at both 3 and 7 days of cytokine stimulation (Figure 6) ▶ . In addition, as the cytokines used in this study have all been identified in KS lesions, a cocktail of all six recombinant cytokines was used to determine whether the cytokines could act synergistically to promote higher levels of HHV-8 replication. Northern blot analysis demonstrated an increase in ORF26 mRNA levels with the cytokine cocktail that were equivalent or slightly higher than levels seen with the individual cytokines alone. Induction of HHV-8 proteins in BCBL-1 cells stimulated with recombinant cytokines was also demonstrated by immunohistochemical staining (Figure 7) ▶ . The results showed significant increases in HHV-8 K8.1 expression for OSM, HGF/SF, and IFN-γ, but not IL-6, TNF-α, or IL-2 at 7 days of stimulation. To confirm that the stimulated cells were indeed in lytic cycle and producing progeny virus, EM analysis of cells stimulated with HGF/SF was performed. As shown in Figure 7 ▶ , viral particles were readily identified in cells.

Figure 6.

Northern blot analysis of ORF26 mRNA expression after stimulation of BCBL-1 cells with recombinant cytokines. A: RNA isolated 3 days after initiation of culture. Lane 1, untreated BCBL-1 cells; lane 2, OSM (2.7-fold increase); lane 3, HGF/SF (3.0-fold increase); lane 4, IFN-γ (4.4-fold increase); lane 5, IL-6 (0.8-fold increase); lane 6, TNF-α (0.5-fold increase); lane 7, IL-2 (no change). B: RNA isolated 7 days after initiation of culture. Lane 1, untreated; lane 2, OSM (3.5-fold increase); lane 3, HGF/SF (4.6-fold increase); lane 4, IFN-γ (4.2-fold increase); lane 5, TNF-α (1.0-fold increase); lane 6, IL-2 (1.7-fold increase); lane 7, Combination of cytokines (4.3-fold increase). Three independent experiments were run with similar results.

Figure 7.

Immunohistochemical staining of cytokine-stimulated BCBL-1 cells (original magnification, ×60). BCBL-1 cells were stimulated for 7 days with recombinant cytokines, cytospin preparations were made and stained for expression of HHV-8 ORF K8.1. BCBL-1 cells alone: 0.4% positive; BCBL-1 cells stimulated with 0.3 mmol/L n-butyrate for 96 hours: 10.5-fold increase in K8.1 expression compared to BCBL-1 alone; BCBL-1 cells stimulated with IFN-γ: 3.6-fold increase (P < 0.05); BCBL-1 cells stimulated with OSM: 4.2-fold increase (P < 0.05); BCBL-1 cells stimulated with HGF/SF: 5.1-fold increase (P < 0.05). Stimulation with IL-2 (1.3-fold increase), TNF-α (1.2-fold increase) or IL-6 (1.7-fold increase) did not result in significant induction of HHV-8 K8.1 (data not shown). Electron microscopy (original magnification, ×20,000) from the BCBL-1 cells stimulated with HGF/SF for 7 days demonstrates the presence of both intranuclear nucleocapsids (arrows) and extracellular virions (data not shown).

Discussion

Previous studies have attempted to explain the high frequency and aggressive nature of KS in HIV-1-positive patients based on the attenuation of the immune system. Although immunosuppression is undoubtedly a component, other factors appear to be involved. The absence of HIV-1 sequences in KS tumor cells themselves suggests that HIV-1 plays an indirect role in KS pathogenesis. 49,50 It has been proposed by Gallo, Ensoli, and colleagues that the role of HIV-1 in KS involves at least two events, cytokine production and production of HIV-1 Tat protein. 51-55 Previous studies demonstrated that inflammatory cytokines, such as OSM, IFN-γ, HGF/SF, IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α, are produced in KS, both by KS tumor cells and mononuclear cells, including infected lymphocytes, infiltrating the lesion in AIDS patients. Many of these cytokines are known to promote the growth and proliferation of KS tumor cells in vitro. 52,56-63 In addition, cytokines have been show to induce normal endothelial cells, the likely precursor cell of the KS tumor cell, to acquire the characteristics typical of KS tumor cells, including spindle-shaped morphology, production of angiogenic factors, and expression of activation markers. These results, and others, have lead to the hypothesis that cytokines play a critical role in the initiation and development of KS by activating endothelial cells, promoting production of angiogenic factors, and providing the necessary growth factors for the tumor cells. 51

In the current study, we demonstrated that cytokines produced by HIV-1-infected cells can induce lytic cycle replication of HHV-8. Several cytokines known to be important in KS, particularly OSM, HGF/SF, and IFN-γ, were able to induce lytic cycle mRNA transcripts and viral proteins resulting in the production of progeny virions. These results are consistent with the above mentioned studies demonstrating the importance of cytokines in KS, and they add additional support to the hypothesis that cytokines may be involved in initiation of KS. As HHV-8 is a lymphotropic virus, a potential mechanism for initiation of KS could involve cytokine stimulation of latently infected mononuclear cells resulting in induction of lytic viral replication and production of viral progeny which can go on to infect endothelial cells. Indeed, recent in situ hybridization studies by Sturzl et al have shown HHV-8-infected mononuclear cells adherent to endothelial cells in KS lesions. 64 This direct contact between infected cells and endothelial cells may be important to infection of the tumor cell precursor. How infected endothelial cells acquire the malignant phenotype is currently unknown, but it may involve subsequent interactions between HHV-8-encoded proteins and host cytokines and/or growth factors. The end result of this host/virus interaction is transdifferentiation of the endothelial cell ultimately leading to the development of full-fledged KS lesions. Indeed, studies have shown that after opportunistic infections, cytokine levels are increased, and opportunistic infections frequently precede the development or growth of KS lesions. 65 In addition, early clinical studies attempting to treat KS with TNF and IFN-γ were unsuccessful due to rapid disease progression in many of the patients. 66-68 Our results are also consistent with recently published studies by Monini et al demonstrating that IFN-γ can induce HHV-8 lytic replication in KS patient PBMCs resulting in prolonged survival of HHV-8 in patients PBMCs in culture. 69 The data in the present study confirm and extend the work of Monini et al, indicating that other cytokines (ie, OSM and HGF/SF) are also able to induce HHV-8 replication, resulting in production of progeny virions. However, Monini and colleagues concluded that the effect of cytokines on HHV-8 replication were specific for PBMCs, as they found no significant differences in latent or lytic viral gene expression in BCBL-1 cells cultured with cytokines. 69 The discrepancy between these reports is likely due to experimental design, including differences such as cytokine concentration, duration of cytokine stimulation, and methods used for analysis of the results.

In the coculture system using HIV-1-infected CEM cells and the HHV-8-infected PEL cell line, BCBL-1, we found that both cells appeared to contribute to the combination of cytokines which induced HHV-8 replication. Of interest, the BCBL-1 cells, but not the CEM or CEM + HIV-1 cells, demonstrated expression of IFN-γ mRNA in RPA assays and coculture supernatants contained IFN-γ proteins as demonstrated by quantitative ELISA. IFN-γ production is generally attributed to T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, not to B cells. However, previous studies have demonstrated the constitutive expression of IFN-γ mRNA by B cell lines as well as the production of IFN-γ protein following stimulation of the cells with various agents including phorbol esters and cytokines. 70,71 The lack of IFN-γ production by the CEM or CEM + HIV-1 cells may be related to this particular T cell line. Indeed, ELISA assays indicated production of OSM (510 ± 21 pg/ml), HGF/SF (337 ± 33 pg/ml), and IFN-γ (19 ± 6 pg/ml) by normal human PBMCs in our coculture system that were equal to or exceeded levels seen with the CEM cells. Thus, cytokines involved in the reactivation of HHV-8 would likely be produced under physiological conditions.

Of course, the results demonstrating the cytokines OSM, HGF/SF, and IFN-γ, which are found in KS lesions and are produced either by HIV-infected cells or in response to HIV-infected cells, can induce HHV-8 replication does not eliminate the possibility that other factors, such as HIV-1-related proteins or additional cytokines, play a role in induction of HHV-8 replication either in vitro or in vivo. Studies by Ensoli, Gallo and colleagues have indicated that extracellular HIV-1 Tat protein can induce growth, migration, invasion and adhesion of both endothelial cells and KS tumor cells, and stimulation of normal endothelial cells with cytokines activates the cells so that they become responsive to Tat protein. 51,72,73 An intriguing brief report by Harrington et al indicates that Tat protein may be able to induce HHV-8 replication; however, this remains to be confirmed. 74

In conclusion, the “cross-talk” demonstrated in this study, whereby HIV-1-infected T cells can induce lytic replication of HHV-8 via specific cytokines, provides new opportunities for targeted intervention in AIDS-related KS. Further studies are clearly indicated to examine more carefully the colocalization of HIV-1 and HHV-8 in sites such as cutaneous KS, as previously observed, to determine whether these in vitro findings are relevant to local tissue levels of HHV-8 in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Linda Fox of the Loyola University Core Imaging Facility for assistance in the preparation of samples for EM and Raoul Fresco, M.D., Ph.D., for expert analysis of EM grids and photographs.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Kimberly E. Foreman, Ph.D., Department of Pathology, Skin Cancer Research Laboratories, Loyola University Oncology Institute, Room 302, 2160 South First Avenue, Maywood, IL 60153-5385. E-mail: kforema@luc.edu.

Supported by U. S. Public Health Service grants CA76951 (to K. E. F.), CA75893 (to B. J. N.), CA63928 (to B. J. N.), CA75911 (to B. C.), and CA82056 (to B. C.).

References

- 1.Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin MS, Lee F, Culpepper J, Knowles DM, Moore PS: Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS- associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Science 1994, 266:1865-1869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore PS, Gao SJ, Dominguez G, Cesarman E, Lungu O, Knowles DM, Garber R, Pellett PE, McGeoch DJ, Chang Y: Primary characterization of a herpesvirus agent associated with Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Virol 1996, 70:549-558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulz TF: Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus-8). J Gen Virol 1998, 79:1573-1591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang YQ, Li JJ, Kaplan MH, Poiesz B, Katabira E, Zhang WC, Feiner D, Friedman-Kien AE: Human herpesvirus-like nucleic acid in various forms of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Lancet 1995, 345:759-761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore PS, Chang Y: Detection of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in Kaposi’s sarcoma in patients with and without HIV infection. N Engl J Med 1995, 332:1181-1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boshoff C, Whitby D, Hatziioannou T, Fisher C, van der Walt J, Hatzakis A, Weiss R, Schulz T: Kaposi’s-sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in HIV-negative Kaposi’s sarcoma. Lancet 1995, 345:1043-1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ambroziak JA, Blackbourn DJ, Herndier BG, Glogau RG, Gullett JH, McDonald AR, Lennette ET, Levy JA: Herpes-like sequences in HIV-infected and uninfected Kaposi’s sarcoma patients. Science 1995, 268:582-583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sitas F, Carrara H, Beral V, Newton R, Reeves G, Bull, Jentsch U, Pacella-Norman R, Bourboulia D, Whitby D, Boshoff C, Weiss R: Antibodies against human herpesvirus 8 in black South African patients with cancer. N Engl J Med 1999, 340:1863–1871 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Kedes DH, Operskalski E, Busch M, Kohn R, Flood J, Ganem D: The seroepidemiology of human herpesvirus 8 (Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus): distribution of infection in KS risk groups and evidence for sexual transmission. Nat Med 1996, 2:918-924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao SJ, Kingsley L, Hoover DR, Spira TJ, Rinaldo CR, Saah A, Phair J, Detels R, Parry P, Chang Y, Moore PS: Seroconversion to antibodies against Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-related latent nuclear antigens before the development of Kaposi’s sarcoma. N Engl J Med 1996, 335:233-241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lennette ET, Blackbourn DJ, Levy JA: Antibodies to human herpesvirus type 8 in the general population and in Kaposi’s sarcoma patients. Lancet 1996, 348:858-861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roizman B: Herpesviridae: a brief introduction. Fundamental Virology, 2d ed. chapter 33. Edited by Fields BN, Knipe DM. New York, Raven Press, 1991, pp 841–847

- 13.Decker LL, Shankar P, Khan G, Freeman RB, Dezube BJ, Lieberman J, Thorley-Lawson DA: The Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is present as an intact latent genome in KS tissue but replicates in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of KS patients. J Exp Med 1996, 184:283-288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarid R, Flore O, Bohenzky RA, Chang Y, Moore PS: Transcription mapping of the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) genome in a body cavity-based lymphoma cell line (BC-1). J Virol 1998, 72:1005-1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dittmer D, Lagunoff M, Renne R, Staskus K, Haase A, Ganem D: A cluster of latently expressed genes in Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol 1998, 72:8309-8315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Neill E, Douglas JL, Chien ML, Garcia JV: Open reading frame 26 of human herpesvirus 8 encodes a tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate- and butyrate-inducible 32-kilodalton protein expressed in a body cavity-based lymphoma cell line. J Virol 1997, 71:4791-4797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu Y, Black JB, Goldsmith CS, Browning PJ, Bhalla K, Offermann MK: Induction of human herpesvirus-8 DNA replication and transcription by butyrate and TPA in BCBL-1 cells. J Gen Virol 1999, 80:83-90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Renne R, Zhong WD, Herndier B, McGrath M, Abbey N, Kedes D, Ganem D: Lytic growth of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) in culture. Nat Med 1996, 2:342-346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller G, Rigsby MO, Heston L, Grogan E, Sun R, Metroka C, Levy JA, Gao SJ, Chang Y, Moore P: Antibodies to butyrate-inducible antigens of Kaposi’s sarcoma- associated herpesvirus in patients with HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med 1996, 334:1292-1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noel JC: Kaposi’s sarcoma and KSHV. Lancet 1995, 346:1359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sturzl M, Blasig C, Schreier A, Neipel F, Hohenadl C, Cornali E, Ascherl G, Esser S, Brockmeyer NH, Ekman M, Kaaya EE, Tschachler E, Biberfeld P: Expression of HHV-8 latency-associated T0.7 RNA in spindle cells and endothelial cells of AIDS-associated, classical and African Kaposi’s sarcoma. Int J Cancer 1997, 72:68-71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedman-Kien AE, Laubenstein LJ, Rubinstein P, Buimovici-Klein E, Marmor M, Stahl R, Spigland I, Kim KS, Zolla-Pazner S: Disseminated Kaposi’s sarcoma in homosexual men. Ann Intern Med 1982, 96:693-700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buchbinder A, Friedman-Kien AE: Clinical aspects of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Curr Opin Oncol 1992, 4:867-874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strathdee SA, Veugelers PJ, Moore PS: The epidemiology of HIV-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma: the unraveling mystery. AIDS 1996, 10(suppl A):S51-S57 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beral V, Peterman TA, Berkelman RL, Jaffe HW: Kaposi’s sarcoma among persons with AIDS: a sexually transmitted infection? Lancet 1990, 335:123-128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ganem D: Human herpesvirus 8 and the biology of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Semin Virol 1996, 7:325-332 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poznansky MC, Coker R, Skinner C, Hill A, Bailey S, Whitaker L, Renton, Weber J: HIV positive patients first presenting with an AIDS defining illness: characteristics and survival. Br Med J 1995, 311:156–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Mocroft A, Youle M, Phillips AN, Halai R, Easterbrook P, Johnson MA, Gazzard B: The incidence of AIDS-defining illnesses in 4883 patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Int Med 1998, 158:491-497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ariyoshi K, Schim vdL, Cook P, Whitby D, Corrah T, Jaffar S, Cham F, Sabally S, O’Donovan D, Weiss RA, Schulz TF, Whittle H: Kaposi’s sarcoma in the Gambia, West Africa is less frequent in human immunodeficiency virus type 2 than in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection despite a high prevalence of human herpesvirus 8. J Hum Virol 1998, 1:193–199 [PubMed]

- 30.Mahoney SE, Duvic M, Nickoloff BJ, Minshall M, Smith LC, Griffiths CE, Paddock SW, Lewis DE: Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transcripts identified in HIV- related psoriasis and Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions. J Clin Invest 1991, 88:174-185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahoney SE, Paddock SW, Smith LC, Lewis DE, Duvic M: Three dimensional laser scanning confocal microscopy of in situ hybridization of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol 1994, 16:44-51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foreman KE, Bacon PE, Hsi E, Nickoloff BJ: In situ PCR-based localization studies support role of HHV-8 as the cause of two AIDS-related neoplasms: Kaposi’s sarcoma and body cavity lymphoma. J Clin Invest 1997, 99:2971-2978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boshoff C, Schulz TF, Kennedy MM, Graham AK, Fisher C, Thomas A, McGee JO, Weiss RA, O’Leary JJ: Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infects endothelial and spindle cells. Nat Med 1995, 1:1274-1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foreman KE, Kash JJ, Eilers DB, Nickoloff BJ: Infection of dendritic cells (DCs) with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8). J Invest Dermatol 1999, 112:603(abstr) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cerimele F, Cesarman E, Curreli F, Hyjek EM, Knowles DM, Flore O: In vitro infection of primary human keratinocytes by Kaposi’s sarcoma associated herpesvirus. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999, 21:A28(abstr) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moses AV, Fish K, Ruhl R, Smith P, Chandran B, Nelson JA: HHV8/KSHV infects dermal endothelial cells and macrophages; implications for Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999, 21:A28(abstr) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cesarman E, Moore PS, Rao PH, Inghirami G, Knowles DM, Chang Y: In vitro establishment and characterization of two acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related lymphoma cell lines (BC-1 and BC-2) containing Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like (KSHV) DNA sequences. Blood 1995, 86:2708-2714 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dayton AI, Sodroski J, Rosen CA, Goh WC, Haseltine WA: The trans-activator gene of the human T cell lymphotropic virus type III is required for replication. Cell 1986, 44:941-957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herrin DL, Schmidt GW: Rapid, reversible staining of northern blots prior to hybridization. Biotechniques 1988, 6:196-200 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Foreman KE, Friborg J, Kong W, Woffendin C, Polverini PJ, Nickoloff BJ, Nabel GJ: Propagation of a human herpesvirus from AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. N Engl J Med 1997, 336:163-171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foreman KE, Alkan S, Krueger AE, Panella JR, Swinnen LJ, Nickoloff BJ: Geographically distinct HHV-8 DNA sequences in Saudi Arabian Iatrogenic Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions. Am J Pathol 1998, 153:1001-1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Longo MC, Berninger MS, Hartley JL: Use of uracil DNA glycosylase to control carry-over contamination in polymerase chain reactions. Gene 1990, 93:125-128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thornton CG, Hartley JL, Rashtchian A: Utilizing uracil DNA glycosylase to control carryover contamination in PCR: characterization of residual UDG activity following thermal cycling. Biotechniques 1992, 13:180-184 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Foreman KE, Wrone-Smith T, Boise LH, Thompson CB, Polverini PJ, Simonian PL, Nunez G, Nickoloff BJ: Kaposi’s sarcoma tumor cells preferentially express Bcl-xL. Am J Pathol 1996, 149:795-803 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chandran B, Bloomer C, Chan SR, Zhu L, Goldstein E, Horvat R: Human herpesvirus-8 ORF K8.1 gene encodes immunogenic glycoproteins generated by spliced transcripts. Virology 1998, 249:140-149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chan SR, Bloomer C, Chandran B: Identification and characterization of human herpesvirus-8 lytic cycle-associated ORF 59 protein and the encoding cDNA by monoclonal antibody. Virology 1998, 240:118-126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu L, Puri V, Chandran B: Characterization of human herpesvirus-8 K8.1 A/B glycoproteins by monoclonal antibodies. Virology 1999, 262:237-249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zoeteweij JP, Eyes ST, Orenstein JM, Kawamura T, Wu L, Chandran B, Forghani B, Blauvelt A: Identification and rapid quantification of early and late lytic human herpesvirus 8 infection in single cells by flow cytometric analysis: Characterization of antiherpesvirus agents. J Virol 1999, 73:5894-5902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jahan N, Razzaque A, Greenspan J, Conant MA, Josephs SF, Nakamura S, Rosenthal LJ: Analysis of human KS biopsies and cloned cell lines for cytomegalovirus, HIV-1, and other selected DNA virus sequences. AIDS Res Hum Retrovirus 1989, 5:225-231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Delli BP, Donti E, Knowles DM, Friedman-Kien A, Luciw PA, Dina D, Dalla-Favera R, Basilico C: Presence of chromosomal abnormalities and lack of AIDS retrovirus DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Cancer Res 1986, 46:6333-6338 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ensoli B, Cafaro A: HIV-1 and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Eur J Cancer Prev 1996, 5:410-412 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ensoli B, Barillari G, Buonaguro L, Gallo RC: Molecular mechanisms in the pathogenesis of AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Adv Exp Med Biol 1991, 303:27-38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Buonaguro L, Buonaguro FM, Tornesello ML, Beth-Giraldo E, Del Gaudio E, Ensoli B, Giraldo G: Role of HIV-1 Tat in the pathogenesis of AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Antibiot Chemother 1994, 46:62-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gallo RC: Some aspects of the pathogenesis of HIV-1 associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 1998, 23:55-57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ensoli B, Barillari G, Gallo RC: Pathogenesis of AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 1991, 5:281-295 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakamura S, Salahuddin SZ, Biberfeld P, Ensoli B, Markham PD, Wong-Staal F, Gallo RC: Kaposi’s sarcoma cells: long-term culture with growth factor from retrovirus-infected CD4+ T cells. Science 1988, 242:426-430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Naidu YM, Rosen EM, Zitnick R, Goldberg I, Park M, Naujokas M, Polverini PJ, Nickoloff BJ: Role of scatter factor in the pathogenesis of AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994, 91:5281-5285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fiorelli V, Gendelman R, Samaniego F, Markham PD, Ensoli B: Cytokines from activated T cells induce normal endothelial cells to acquire the phenotypic and functional features of AIDS- Kaposi’s sarcoma spindle cells. J Clin Invest 1995, 95:1723-1734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ensoli B, Nakamura S, Salahuddin SZ, Biberfeld P, Larsson L, Beaver B, Wong-Staal F, Gallo RC: AIDS-Kaposi’s sarcoma-derived cells express cytokines with autocrine and paracrine growth effects. Science 1989, 243:223-226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Samaniego F, Markham PD, Gallo RC, Ensoli B: Inflammatory cytokines induce AIDS-Kaposi’s sarcoma-derived spindle cells to produce and release basic fibroblast growth factor and enhance Kaposi’s sarcoma-like lesion formation in nude mice. J Immunol 1995, 154:3582-3592 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miles SA, Martinez-Maza O, Rezai A, Magpantay L, Kishimoto T, Nakamura S, Radka SF, Linsley PS: Oncostatin M as a potent mitogen for AIDS-Kaposi’s sarcoma-derived cells. Science 1992, 255:1432-1434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ensoli B, Barillari G, Gallo RC: Cytokines and growth factors in the pathogenesis of AIDS- associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Immunol Rev 1992, 127:147-155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cai J, Gill PS, Masood R, Chandrasoma P, Jung B, Law RE, Radka SF: Oncostatin-M is an autocrine growth factor in Kaposi’s sarcoma. Am J Pathol 1994, 145:74-79 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sturzl M, Wunderlich A, Ascherl G, Hohenadl C, Monini P, Zietz C, Browning PJ, Neipel F, Biberfeld P, Ensoli B: Human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8) gene expression in Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) primary lesions: an in situ hybridization study. Leukemia 1999, 13 (suppl. 1):S110-S112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Emmanoulides C, Miles SA, Mitsuyasu RT: Pathogenesis of AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma. Oncology 1996, 10:335-341 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aboulafia D, Miles SA, Saks SR, Mitsuyasu RT: Intravenous recombinant tumor necrosis factor in the treatment of AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1989, 2:54-58 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Krigel RL, Odajnyk CM, Laubenstein LJ, Ostreicher R, Wernz J, Vilcek J, Rubinstein P, Friedman-Kien AE: Therapeutic trial of interferon-gamma in patients with epidemic Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Biol Response Mod 1985, 4:358-364 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ganser A, Brucher W, Brodt HR, Busch W, Brandhorst I, Helm EB, Hoelzer D: Treatment of AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma with recombinant gamma-interferon. Onkologie 1986, 9:163-166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Monini P, Colombini S, Sturzl M, Goletti D, Cafaro A, Sgadari C, Butto S, Franco M, Leone P, Fais S, Melucci-Vigo G, Chiozzini C, Carlini F, Ascheri G, Cornali E, Zietz C, Ramazzotti E, Ensoli F, Andreoni M, Pezzotti P, Rezza G, Yarchoan R, Gallo RC, Ensoli B: Reactivation and persistence of human herpesvirus-8 infection in B-cells and monocytes by Th-1 cytokines increased in Kaposi’s sarcoma. Blood 1999, 93:4044-4058 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pang Y, Norihisa Y, Benjamin D, Kantor RR, Young HA: Interferon-gamma gene expression in human B-cell lines: induction by interleukin-2, protein kinase C activators, and possible effect of hypomethylation on gene regulation. Blood 1992, 80:724-732 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dayton MA, Knobloch TJ, Benjamin D: Human B cell lines express the interferon gamma gene. Cytokine 1992, 4:454-460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ensoli B, Buonaguro L, Barillari G, Fiorelli V, Gendelman R, Morgan RA, Wingfield P, Gallo RC: Release, uptake, and effects of extracellular human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein on cell growth and viral transactivation. J Virol 1993, 67:277-287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barillari G, Gendelman R, Gallo RC, Ensoli B: The Tat protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1, a growth factor for AIDS Kaposi sarcoma and cytokine-activated vascular cells, induces adhesion of the same cell types by using integrin receptors recognizing the RGD amino acid sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993, 90:7941-7945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Harrington WJ, Sieczkowski L, Sosa C, Chan H, Cai JP, Cabral, Wood C: Activation of HHV-8 by HIV-1 tat (letter). Lancet 1997, 349:774–775 [DOI] [PubMed]