Abstract

Alport syndrome is an inherited nephropathy characterized by alterations of the glomerular basement membrane because of mutations in type IV collagen genes. COL4A5 mutations, causing X-linked Alport syndrome, frequently result in the loss of the α5 chains of type IV collagen in basement membranes. This is associated with the absence of the α3(IV) and α4(IV) chains and increased amounts of α1(IV) and α2(IV) in glomerular basement membranes. The mechanisms resulting in such a configuration are still controversial and are of fundamental importance for understanding the pathology of the disease and for considering gene therapy. In this article we studied, for the first time, type IV collagen expression in kidneys from X-linked Alport syndrome patients, using in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry. We show that, independent of the type of mutation and of the level of COL4A5 transcription, both COL4A3 and COL4A4 genes are actively transcribed in podocytes. Moreover, using immunofluorescence amplification, we were able to demonstrate that the α3 chain of type IV collagen was present in the podocytes of all patients. Finally, the α1(IV) chain, which accumulates within glomerular basement membranes, was found to be synthesized by mesangial/endothelial cells. These results strongly suggest that, contrary to what has been found in dogs affected with X-linked Alport syndrome, there is no transcriptional co-regulation of COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5 genes in humans, and that the absence of α3(IV) to α5(IV) in glomerular basement membranes in the patients results from events downstream of transcription, RNA processing, and protein synthesis.

Alport syndrome (AS) is an inherited disorder of the glomerular basement membrane (GBM) characterized by hematuria, progressive renal failure, and sensorineural hearing loss, frequently associated with ocular abnormalities such as lenticonus and retinal anomalies. 1-4 AS is caused by defects in type IV collagen, a major component of basement membranes. 5 Six α(IV) collagen chains, α1(IV) to α6(IV), have been identified so far in mammals. They are encoded by six distinct genes, COL4A1 to COL4A6, localized pairwise on three chromosomes. 6-11 COL4A5 mutations lead to the most common form of AS which is X-linked, whereas COL4A3 and COL4A4 mutations are responsible for the autosomal recessive forms. 12-19

The primary structure of the six α(IV) chains is very similar. Each is characterized by an ∼25-residue noncollagenous domain at the amino terminus, an ∼1400 residue collagenous domain of Gly-X-Y repeats (in which X is frequently proline and Y is frequently hydroxyproline), that forms, in association with two other chains, the triple helix, and an ∼230-residue noncollagenous (NC1) domain at the carboxyl terminus. 9,20,21 The amino terminus of the collagenous domain is involved in the tetramerization of triple helical molecules, whereas the NC1 domain is involved in their dimerization. This organization eventually leads to the formation of a three-dimensional tight network that forms the scaffold of the basement membrane. The expression of the six α(IV) chain proteins and mRNA varies from one tissue to another. The α1(IV) and α2(IV) chains are expressed in all basement membranes, mainly in the form of the [α1(IV)]2-α2(IV)] trimer, whereas the α3(IV) to α6(IV) chains have a tissue-restricted distribution. In the human and rodent kidney, immunohistochemical studies have shown a low-level expression of α1(IV) to α2(IV) in mature GBM whereas the α3(IV) to α5(IV) chains are highly expressed. 22-27 Little is known about the different isoforms of triple-helical type IV collagen molecules, 5,28 and their supramolecular organization in the different basement membranes. However, different subpopulations of NC1 hexamers, which reflect the association of two triple-helical molecules within the type IV collagen network, have been described recently in GBM as well as in other basement membranes. 28-31 The presence of cysteine-rich α3(IV) and α4(IV) chains, forming with α5(IV) a network containing loops and supercoiled triple helices stabilized by disulfide bonds between the chains, seems to be important with regards to the long-term stability of the GBM and its role as a filter. 26,32

Despite the increasing number of AS mutations reported in the literature 12-19 and the existence of AS animal models, 33-37 several questions regarding the consequences of AS mutations on the collagen organization within the GBM and the mechanisms responsible for the progressive development of AS nephropathy remain unanswered. A striking feature observed in the majority of AS is the absence of all three α3(IV), α4(IV), and α5(IV) chains within the GBM although only one of these chains is actually mutated. 13,24-27,32,38-42 This suggests that transcriptional, translational, and/or posttranslational events link the expression of the different type IV collagen chains. Furthermore, the α1 and α2 chains, which are normally confined to the subendothelial aspect of the GBM, and presumed to be synthesized by mesangial/endothelial cells in the normal kidney, are strongly expressed across the entire width of the GBM in AS patients. 43 The cellular origin, whether mesangial-subendothelial or epithelial, of these two chains in AS GBM, remains to be elucidated. To address these questions, we analyzed the expression of type IV collagen chains in glomeruli from normal controls and patients with X-linked AS, both at the transcriptional and at the protein level.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Renal specimens from six unrelated AS male patients previously shown to be lacking α3(IV) to α5(IV) isoforms within their GBM were used for this study. Clinical, morphological, and genetic data are presented in Table 1 ▶ . All patients were affected with a severe (juvenile) disease. X-linked transmission was demonstrated on the basis of pedigree structure (5 patients), linkage analysis (3 patients), and/or the demonstration of a COL4A5 mutation (4 patients) which has been previously reported. 12,13

Table 1.

Clinical, Morphological, and Genetic Data in the Six X-Linked Alport Syndrome Patients

| Patients | Family history | Age at ESRD | Hearing loss | Ocular lesions | GBM changes | GBM antigeniticy | COL4A5 mutations | Effect on coding sequence | Exon (Reference) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | + | −* | + | + (L) | T+t | − | Deletion | Frameshift | 3 → 41 (12) |

| 2 | + | 14 | + | + (L) | nd | − | del of G at 890-1/891 | Frameshift | 13 (13) |

| 3 | [−] | 14 | + | − | T+t | − | A → T at 3807-3 | 3′ splice | 41 (13) |

| 4 | + | 13 | + | − | nd | − | nd | / | / |

| 5 | + | 11 | + | − | T+t | − | nd | / | / |

| 6 | + | −* | + | + (M) | T | − | G → C at 3398 | Gly → Arg at 1066 | 36 (13) |

L, lenticonus; M, maculopathy; T, thickening and splitting of the GBM; T+t, alternatively thick and thin GBM; nd, not determined.

*Chronic renal failure was observed in patient 1 at 23 years and in patient 6 at 26 years.

Immunohistology

Antibodies

Commercially available affinity-purified antibodies raised against pepsin-digested human placenta type IV collagen were obtained from Pasteur-Lyon (Lyon, France). They recognize the collagenous domain of the [α1(IV)2 α2(IV)] collagen protomer. Monoclonal antibodies recognizing the NC1 domain of, respectively, the α1 (mAb1), α3 (mAb3), and α5 (mAb 5) chains of type IV collagen were from Wieslab (Lund, Sweden). Monoclonal antibodies against the NC1 domain of the α4 chain of type IV collagen (mAb 85) (22) were a gift from MM Kleppel, (22) and monoclonal antibodies against the NC1 domain of the α6(IV) chain (H63) were from Y Sado. 23

Affinity-purified fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated sheep immunoglobulin G anti-rabbit and anti-mouse immunoglobulins were from Silenius (Victoria, Australia). Fluorescein-conjugated affinity-purified donkey anti-sheep immunoglobulin G (H+L) antibodies were from Jackson Laboratories (West Grove, PA).

Standard Indirect Immunofluorescence and Amplification Technique

Renal tissues from the six AS patients were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen using cryo-M-bed (Bright Instrument Co., Huntingdon, UK). Cryostat sections (3-μm thick) were air dried and fixed in acetone for 10 minutes. Sections to be stained with mAb 85 and mAb A7 were pretreated with 0.1 mol/L glycine, 6 mol/L urea, pH 3.5, for 10 minutes, then rinsed with distilled water, as previously described. 39 After washing in fresh buffer (0.01 mol/L phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4), sections were incubated in a moist chamber with the appropriate dilution of monoclonal antibodies against the α1, α3, α4, α5, and α6 chains of type IV collagen before incubation with fluorescein isothiocyanate sheep anti-mouse antibodies (1/20). For amplification of the signal, a further incubation with fluorescein isothiocyanate donkey-anti-sheep antibodies (1/50) was performed. A mounting media containing p-phenylenediamine was used to delay fluorescence quenching. Labeling was examined with a Leitz Orthoplan microscope (Leica Microscopic Systems, Heezbrugg, Switzerland) equipped with appropriate filters. Tissue sections directly incubated with secondary antibodies served as a control for nonspecific binding, and negative results were obtained in all cases. Four normal kidneys (two nontransplanted kidneys and normal renal tissue adjacent to renal cell carcinoma in two patients) and 12 renal biopsy specimens of patients presenting various types of acquired glomerulopathies were tested as controls.

In Situ Hybridization

Riboprobe Transcription

Recombinant plasmids for type α(IV) collagen chain cDNA, restriction enzymes for linearization, and RNA polymerase used for in vitro transcription to generate anti-sense and sense cRNA probes are presented in Table 2 ▶ .

Table 2.

Recombinant Plasmids, Restriction Enzymes Used for Linearization, RNA Polymerases Used to Generate Antisense and Sense mRNA Probes

| Chain | Insert length (bp) | Plasmid | Anti-sense probe | Sense probe | Location in cDNA (reference) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | Promotor | Enzyme | Promotor | ||||

| α1 | 533 | PCRTMII | HindIII | T7 | EcoRV | Sp6 | NC1 domain |

| (1–533 of NC domain) | |||||||

| (44) | |||||||

| α3 | 462 | pBSII SK | EcoRV | T3 | EagI | T7 | NC1 domain (4357–4819) |

| (45) | |||||||

| α4 | 760 | pBSII KS | EcoRV | T7 | EagI | Sp6 | NC1 domain (4521–5281) |

| (46) | |||||||

| α5 | 579 | pBSII SK | EcoRV | T3 | EagI | T7 | Collagenous domain |

| (1921–2500) (47) |

Labeled RNA probes were synthesized with Sp6, T7, or T3 RNA polymerases (Boehringer-Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) using 35S-UTP (Amersham, Brauschweig, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. They were DNaseI-treated (Boehringer-Mannheim) immediately after the RNA polymerase reaction. After purification by ammonium acetate-ethanol precipitation, the probes were dissolved in 10 mmol/L Tris, 1 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 20 mmol/L dithiothreitol, and stored at −80°C. Anti-sense and sense strands were synthesized for all riboprobes.

In Situ Hybridization

In patients 1 to 3, nephrectomy specimens obtained at the time of renal transplantation were used for in situ hybridization techniques. In all specimens preserved glomeruli were focally present between sclerotic areas. For technical reasons (too long of a time between nephrectomy and fixation revealed by the absence of labeling with COL4A1 anti-sense probes), in situ hybridization studies could not be performed in patients 4 and 5. Tissue from the small biopsy specimen of patient 6 was no longer available. Controls were performed on the four normal kidneys.

In situ hybridization was performed according to the protocol previously published. 48 In brief, 6-μm thick deparaffinized sections of formaldehyde-fixed tissue were pretreated by microwave heating for 7 and 5 minutes in a citric acid buffer (0.01 mol/L, pH 6.0) to enhance the hybridization signal. 49 They were postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, then digested for 20 minutes with proteinase K. After dehydration and air-drying, each section was covered with 30 μl of diluted heat-denaturated riboprobe in hybridization mixture (3–4 × 10 5 cpm/section) and incubated overnight in a humid chamber at 50°C. Slides were washed in solutions of increasing degrees of stringency (from 5× sodium chloride-sodium citrate with 50% formamide at 55°C to 0.01× sodium chloride-sodium citrate at room temperature) and digested with RNase A (50 mg/ml) to remove the unhybridized single-stranded RNA. Finally, the sections were dehydrated through increasing concentrations of ethanol diluted in 0.3 mol/L of ammonium acetate and air-dried. The hybridization signal was estimated macroscopically after autoradiography of sections using Biomax film (Kodak, Rochester, NY) for 1 to 3 days. Microscopic autoradiographic images were obtained by dipping the same slides in NTB-2 X-ray emulsion (Kodak) and exposing for 5 to 12 weeks depending on the autoradiogram intensity. Exposed slides were photographically developed in D-19 developer (Kodak) and fixed in G333C fixer (Agfa, Geveant, Belgium). After light counterstain with toluidine blue, the slides were dehydrated with ethanol and mounted. They were examined by four independent observers (LH, YC, LG, MCG) with a Leitz microscope fitted with phase-contrast and dark-field optics.

In each experiment, normal and AS kidney sections were simultaneously hybridized with sense and anti-sense probes, and developed for comparative evaluation of the hybridization signal. No specific labeling was detected with sense probes, this being the reason why only one example of sense probe hybridization was shown.

Results

The α3(IV), α4(IV), and α5(IV) Chains Are Synthesized by the Podocyte and the α1(IV) Chain Is Synthesized by Mesangial/Endothelial Cells in Normal Glomeruli

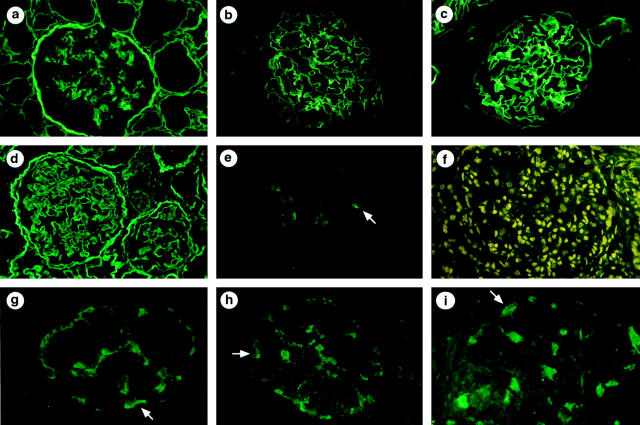

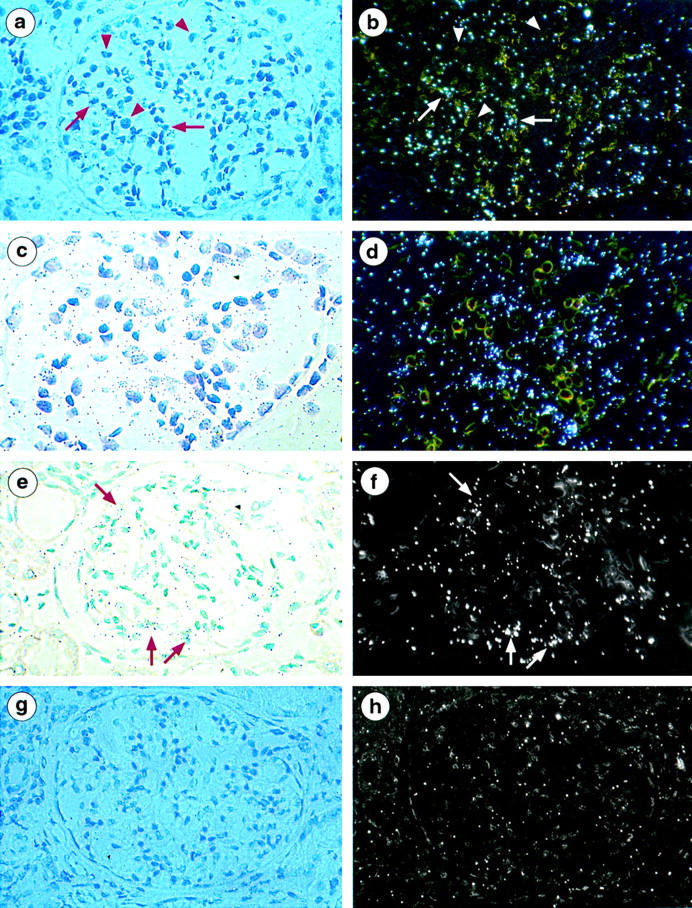

COL4A1 transcripts, but not COL4A3 to COL4A5 transcripts, could be detected in endocapillary cells (mesangial and endothelial cells could not be differentiated because of their close contact) and Bowman’s capsule epithelial cells but not in podocytes (Figure 1, a and b) ▶ . In contrast, sections probed for α3(IV), α4(IV), or α5(IV) mRNA exhibited silver labeling on cells regarded as podocytes because of their localization on the periphery of the glomerular tuft, their large size, and their pale oval-shaped nucleus (Figure 1, c–f) ▶ . No signal was detected on endocapillary cells (mesangial or endothelial) cells. No specific labeling was observed with sense probes (Figure 1, g and h) ▶ . In addition, COL4A1 transcripts were observed in arterial walls and focally in tubular cells and faint expression of COL4A3 to COL4A5 transcripts was focally detected in distal tubular cells (data not shown). These findings are consistent with the previously established immunohistochemical localization of the α(IV) chains within the normal kidney (Figure 2, a–c) ▶ . Within normal glomeruli, no glomerular cell labeling was detected with any of the anti-α1(IV) to anti-α6(IV) antibodies.

Figure 1.

Kidney localization of α1(IV), α3(IV), and α5(IV) mRNA in controls with 35S-labeled anti-sense riboprobes. a and b: Bright-field and dark-field micrografts using α1(IV) anti-sense probes show silver grains distributed focally over capsular epithelial cells and within mesangial stalks (arrow). Podocytes characterized by their large oval-shaped nucleus are unstained (arrowhead). c and d: Bright-field and dark-field micrografts using α3(IV) anti-sense probes show clusters of grains in the periphery of capillary loops overlying podocytes. Endocapillary cells characterized by their small dark nucleus are unlabeled. e and f: Bright-field and dark-field micrografts using α5(IV) anti-sense probes also show clusters of grains in the periphery of capillary loops overlying podocytes (arrow). g and h: Bright-field and dark-field micrografts using α1(IV) sense probes show no specific signal. Magnification, ×250 (a, b and e–h), ×350 (c and d).

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical distribution of type IV collagen α1, α3, and α5 chains in the kidney of controls (a–c) and X-linked AS male patients (d–i). Controls: a, anti-α1(IV) antibodies strongly stained the mesangial matrix, Bowman’s capsule, and tubular basement membranes and reacted faintly with the GBM; b, anti-α3(IV) antibodies stained the GBM; and c, with anti-α5(IV) antibodies, the GBM and also the Bowman’s capsule are strongly stained. AS patients: d, strong and diffuse labeling of the GBM is observed with anti-α1(IV) antibodies; e, no GBM labeling is observed with anti-α3(IV) antibodies but faint staining of two podocytes (arrow) is seen (patient 1); f, absence of GBM staining with anti-α5(IV) antibodies; g–i, after amplification of the α3(IV) signal, strong podocyte labeling is observed (arrow) (patients 1, 2, and 5). Magnification, ×150 (a–e, g and h), ×180 (f), ×240 (i).

The α1(IV) Chain Which Accumulates within the GBM in AS Patients Is Synthesized by Mesangial/Endothelial Cell

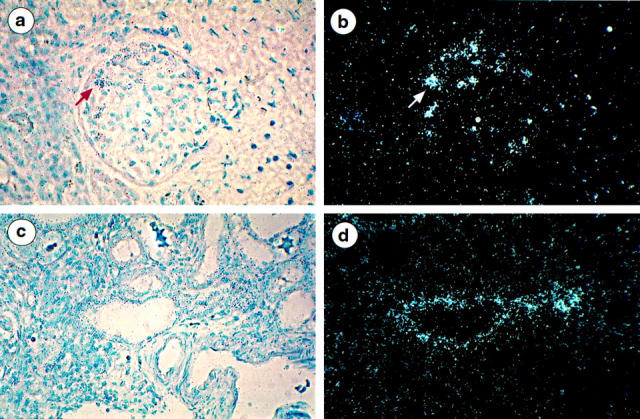

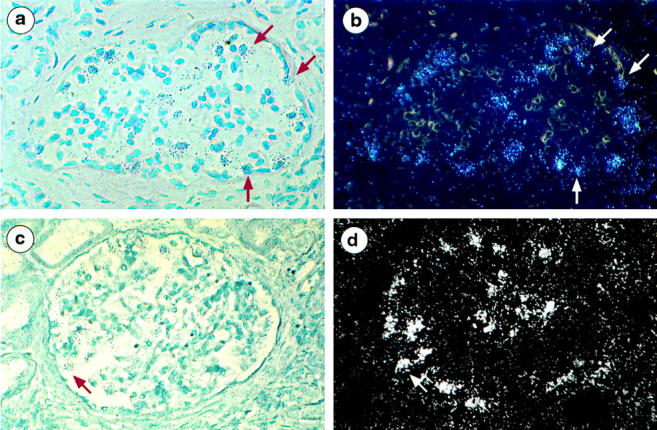

Contrasting with the absence of GBM staining with anti-α3(IV), anti-α4(IV), or anti-α5(IV) antibodies (Figure 2, e ▶ and f), a strong GBM staining with anti-type IV collagen [α1(IV)2 α2(IV)] and anti-α1(IV) antibodies was observed in AS patients (Figure 2d) ▶ , as previously published by us and others in most X-linked AS. 13,24-27,38,40-42 To determine the origin of these chains, in situ hybridization was performed in three patients. Moderate (patient 1) to marked (patients 2 and 3) labeling of endocapillary cells was observed (Figure 3, a and b) ▶ . Although this technique does not allow quantification of the level of transcription, the intensity of the signal was consistently higher in patient kidneys compared with control kidneys. It was associated with strong expression of α1(IV) mRNAs by capsular epithelial cells, particularly in glomeruli undergoing sclerosis. No podocyte expression of α1(IV) RNA was detected in AS patients whereas focal labeling of tubular cells was seen as in normal kidneys. In addition, hybridization signals more intense than those seen on tubular cells were observed within interstitial cells, particularly in areas of interstitial fibrosis (Figure 3, c and d) ▶ .

Figure 3.

Localization of α1(IV) mRNA in the kidney of AS patients using 35S-labeled anti-sense riboprobes. a and b: Bright-field and dark-field micrografts show clusters of silver grains over Bowman’s capsule epithelial cells (arrowhead) and mesangial cells (arrow). Podocytes characterized by their pale oval-shaped nucleus are unlabeled. c and d: : Bright-field and dark-field micrografts show silver grains focally distributed over tubular cells and accumulated in clusters over peritubular interstitial cells (arrow). Magnification, ×220 (a–d).

The COL4A5 Transcript Is Strongly Expressed by Podocytes in One X-Linked AS Patient with a COL4A5 Splice-Site Mutation

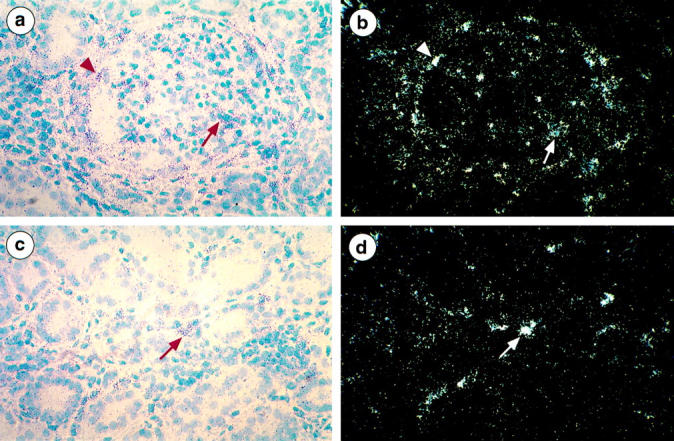

Using COL4A5 RNA anti-sense probes, no signal was detected in the podocytes of patients 1 and 2. Patient 1 has a large intragenic COL4A5 deletion extending from exon 3 to 41 and patient 2 has a deletion of G in exon 13. Both deletions would result in a frameshift mRNA. In contrast clusters of silver grains were concentrated over the podocytes of patient 3, who carries a splice site mutation involving the 3′ end of COL4A5 intron 40 (Figure 4, a and b) ▶ . Strong expression of the transcript in distal and collecting ducts was focally seen as well (Figure 4, c and d) ▶ . However, the related α5(IV) chain as well as the α3(IV) and α4(IV) chains were absent from renal basement membranes.

Figure 4.

Localization of α5(IV) mRNA in the kidney of AS patient 3 using 35S-labeled anti-sense riboprobes. a and b: Bright-field and dark-field micrografts show clusters of silver grains overlying focally cells in the periphery of the glomerular tuft (arrow). c and d: Epithelial cells of one tubular section are strongly labeled with the probe. Magnification, ×220 (a–d).

The COL4A3 and COL4A4 Transcripts Continue to Be Expressed by Podocytes in X-Linked AS

In the three AS patients studied by in situ hybridization, clusters of silver grains were observed over podocytes with COL4A3 and COL4A4 RNA anti-sense probes (Figure 5, a–d) ▶ . Signals were more intense than those obtained from normal kidneys under the same conditions of hybridization and exposure suggesting an increased level of transcription of these genes in the patients. Strong signals for both transcripts were focally observed in some groups of dilated or atrophic tubules (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Localization of α3(IV) and α4(IV) mRNA in the kidney of AS patients using 35S-labeled anti-sense riboprobes. a and b: Bright-field and dark-field micrografts using α3(IV) anti-sense probes show large clusters of silver grains over cells regarded as podocytes on their localization at the periphery of capillary loops (arrow). c and d: Bright-field and dark-field micrografts using α4(IV) anti-sense probes show clusters of silver grains overlying podocytes (arrow). Magnification, ×220 (a–d).

The α3(IV) Protein Is Expressed by Podocytes in X-Linked AS

By standard immunofluorescence, contrasting with the absence of GBM staining, the anti-α3(IV) antibodies weakly stained podocytes in AS patients 1 and 2 (Figure 2e) ▶ . This surprising finding prompted us to attempt to amplify the fluorescent signal. Amplification of the α3(IV) signal showed podocytes to be negative in normal kidneys as well as in 11 of the 12 control kidneys affected with various non-AS types of nephropathy. In only one patient, a 1-year-old boy with glomerular lesions secondary to severe renovascular hypertension, could a faint and focal podocyte labeling be detected. However, in all AS kidneys, podocyte staining was observed after α3(IV) labeling amplification. The expression of α3(IV) was intense and diffuse in patients 1, 2, 3, and 5 (Figure 1, g–i) ▶ and moderate and/or focal in the two others. No podocyte staining could be observed after amplification of α4(IV) or α5(IV) labeling in control or in AS kidneys.

Discussion

Because of the very low level of transcription of type IV collagen genes and the slow rate of type IV collagen protein turn-over in mature kidney, 50 only fragmentary data are available regarding the source of the different α(IV) chains present in the normal glomerular extracellular matrix. 51-54 In this study, we show that the α1(IV) chain is synthesized by glomerular endocapillary cells in the human mature kidney. COL4A1 transcripts are also detected in capsular epithelial cells but not in visceral epithelial cells. Podocytes, in contrast, synthesize the α3(IV), α4(IV), and α5(IV) chains. These results are in agreement with the data recently reported in rodents 51-54 and are consistent with the localization of the related proteins within the glomerular extracellular matrix: α1(IV) is observed in association with α2(IV) in the mesangial areas and the subendothelial aspect of the GBM, whereas α3(IV), α4(IV), and α5(IV) are present across the full width of the GBM. Moreover, they indicate that podocytes can be considered as the primary target for gene therapy of AS.

In ∼30% of patients with COL4A5 mutations, mainly consisting of missense or splicing mutations, the GBM distribution of the α(IV) chains is normal showing that some mutated chains can indeed assemble within the GBM collagenous network. 4,13,27,38,40-42 This normal pattern is usually observed in patients with a milder form of AS disease, characterized by the onset of end stage renal disease after 30 years, and the thin, rather than thick, GBM. 42 However, in most X-linked AS patients, the α5 chain of type IV collagen is absent from the GBM, as are the α3(IV) and α4(IV) chains although encoded by autosomal genes. 4,13,24-27,38,40-42 Similarly, the co-absence of the three chains in the GBM is also observed in autosomal recessive AS because of COL4A3 or COL4A4 mutations. 39 The same holds true in Samoyed dogs affected with an X-linked nephritis closely resembling the human AS, and because of a stop mutation in COL4A5 exon 35 55 and in mouse or dog models for autosomal recessive AS. 35-37 In these situations the α3(IV) to α5(IV) network is replaced, throughout the width of AS GBM, by an α1(IV) to α2(IV) network which is normally confined to the subendothelial region of the GBM. The precise mechanisms resulting in the lack of all three chains when only one gene is mutated and in their replacement by ubiquitous α1(IV) and α2(IV) chains remains speculative.

In this article, we studied the glomerular expression of the different type IV collagen chains at the transcriptional and at the protein level in X-linked AS kidneys, all lacking α3(IV) to α5(IV) chains in their GBM. In three out of the six X-linked AS patients we report here, we were able to perform in situ hybridization. Two of these, affected with a frameshift mutation and a large deletion, respectively, had no detectable COL4A5 transcript, a result similar to that reported in the Samoyed dog 55 and suggesting that such mutations are responsible for destabilization of the mutated message and its rapid degradation. 35,36 In the third patient, affected with a 3′ splice mutation, a COL4A5 transcript was clearly expressed. Splicing of such RNA would be predicted to give rise either to a transcript with an in-frame deletion (arising from exon skipping), and/or to an out-of-frame transcript and a putative truncated protein. Using COL4A3 and COL4A4 riboprobes, we show that COL4A3 and COL4A4 transcripts were readily detected in podocytes of these three patients, and hybridization signals were more intense than those obtained under the same conditions in normal controls. As this study was performed on a retrospective collection of human tissues, we cannot assume that differences observed were significant, but they are consistent with the slight increase in COL4A4 and COL4A5 expression detected in total kidney of AS mice lacking α3(IV). 35 These data indicate that, in humans, contrary to what has been observed in Samoyed AS dogs, 55 the level of expression of the three genes is not co-regulated, and that COL4A3 and COL4A4 are actively transcribed independently of the level of COL4A5 transcription and the type of COL4A5 mutation. This evidence highly suggests a posttranscriptional regulation for the co-expression of the type IV collagen chains in humans, which has been documented to occur for other collagens. 56-59 There are several other arguments which support a posttranscriptional regulation for type IV collagen chains. In humans, a normal level of COL4A3 and COL4A4 expression was suggested by semiquantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction analysis of AS patients’ kidneys. 60 In the mouse model for autosomal recessive AS produced by COL4A3 gene targeting, the co-absence of the three α3(IV) to α5(IV) chains in the GBM is observed despite a normal 36 or slightly increased 35 expression of COL4A4 and COL4A5 mRNAs. Similarly, in X-linked AS male patients without detectable α5(IV) and α6(IV) protein at the dermo-epidermal junction (where these two chains are normally co-expressed), a normal level of transcription of COL4A6 was observed in cultured fibroblasts. 61 In the same way, the α6(IV) mRNA level was found to be normal in bladder smooth muscle of Samoyed AS dogs, despite the absence of the α6(IV) chain. 62 The presence in the GBM of a supramolecular network including α3(IV), α4(IV), and α5(IV) chains, covalently linked by disulfide bonds further supports the hypothesis of the requirement of one chain for the assembly of the two others. 28-30 Such a mechanism has been well documented in Caenorhabditis elegans affected with embryonic lethal mutations of COL4A1 or COL4A2. In these animals, type IV collagen is reduced or absent from basement membranes, but is correspondingly seen to accumulate within the cells that synthesize it, possibly because of the high rate of α1(IV) to α2(IV) chain synthesis during development. 63

Using the immunofluorescence amplification technique and antibodies directed against the NC1 domain of the chain, we have been able to demonstrate for the first time the presence of the α3(IV) protein within human AS podocytes, a finding very special to AS patients, not seen in normal kidneys, and exceptional in other pathological conditions. The presence of both the transcripts and the protein indicate that the loss of the α3(IV) chain in X-linked AS GBM results from events downstream of transcription, RNA processing, and protein synthesis. Previous studies have shown that the switch in type IV collagen chains that normally occurs during kidney development is arrested in AS. 26 Our study suggests that this switch normally occurs in AS podocytes, which express COL4A3 and COL4A4 RNAs. A lower rate of α4(IV) protein synthesis, by comparison with α3(IV) might be the reason why we could not detect this chain in podocytes using the same technique, but this question remains open.

All these results demonstrate that in humans, the absence or the synthesis of an abnormal α5(IV) chain can prevent the integration of the α3(IV) to α4(IV) chains which continue to be normally synthesized by podocytes. This could occur, either within the cell if these chains form heterotrimers with α5(IV), or at the supramolecular level, within the GBM α3(IV) to α5(IV) network.

In AS patients or animal models lacking the α3(IV), α4(IV), and α5(IV) chains, α1(IV) and α2(IV) are abundant in the GBM, an observation consistent with several published reports. 22,26,42,43 This is thought to be responsible for an increased susceptibility to proteolytic attack, possibly because α1(IV) and α2(IV) contain less cysteine 26 than the α3(IV), α4(IV), and α5(IV) chains and form a network without loops and supercoiling of the triple helix. 30 The cell source of the α1(IV) and α2(IV) chains which accumulate within the GBM had not been investigated. In this paper, we show that α1(IV) messages are present in endocapillary cells. Signals were stronger than in controls, but as previously indicated no quantitative evaluation could be done. Strong signals for α1(IV) transcripts were also observed in capsular epithelial cells, especially in glomeruli progressing to sclerosis. In addition, the α1(IV) message was demonstrated in interstitial cells, a localization not detected in normal kidneys, indicating that classical type IV collagen synthesized by interstitial cells might participate in the development of interstitial fibrosis, a prominent feature in chronic AS nephropathy. The increase in α1(IV) mRNA observed in kidney from mutant AS mice as glomerular sclerosis and interstitial fibrosis are progressing, 35 may be due in a large extent to the de novo synthesis of type IV collagen by interstitial cells.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Marie Claire Gubler, INSERM U423, Tour Lavoisier, Hôpital Necker Enfants Malades, 149, rue de Sèvres, 75743 Paris Cedex 15, France. E-mail: gubler@necker.fr.

Supported by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, the Association Claude-Bernard, the Association pour l’Utilisation du Rein Artificiel, the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale, and the Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale.

References

- 1.Alport AC: Hereditary familial congenital haemorrhagic nephritis. BMJ 1927, 1:504-506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkin CL, Gregory MC, Border WA: Alport syndrome. ed 4 Schrier RW Gottschalk CW eds. Diseases of the Kidney, 1988, :pp 617-647 Little Brown and Company, Boston [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flinter FA, Cameron JS, Chantler C, Houston I, Bobrow M: Genetics of classic Alport’s syndrome. Lancet 1988, 2:1005-1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gubler MC, Antignac C, Deschênes G, Knebelmann B, Hors-Cayla MC, Grünfeld JP, Broyer M, Habib R: Genetic, clinical and morphologic heterogeneity in Alport’s syndrome. Adv Nephrol 1993, 22:15-35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Timpl R: Structure and biochemical activity of basement membrane proteins. Eur J Biochem 1989, 180:487-502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soininen R, Huotari M, Hostikka SL, Prockop DJ, Tryggvason K: The structural genes for alpha1 and alpha2 chains of human type IV collagen are divergently encoded on opposite DNA strands and have an overlapping promoter region. J Biol Chem 1988, 263:17217-17220 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hostikka SL, Eddy RL, Byers MG, Hoyhtya M, Shows TB, Tryggvason K: Identification of a distinct type IV collagen a chain with restricted kidney distribution and assignment of its gene to the locus of X-linked Alport syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990, 87:1606-1610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mariyama M, Zheng KG, Yang FT, Reeders ST: Colocalization of the genes for the alpha3(IV) and alpha4(IV) chains of type-IV collagen to chromosome 2 bands 2-q35–q37. Genomics 1992, 13:809-813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hudson BG, Reeders ST, Tryggvason K: Type IV collagen: structure, gene organization, and role in human diseases. Molecular basis of Goodpasture and Alport syndromes and diffuse leiomyomatosis. J Biol Chem 1993, 268:26033-26036 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou J, Ding M, Zhao Z, Reeders ST: Complete primary structure of the sixth chain of human basement membrane collagen α6(IV). Isolation of the cDNAs for α6(IV) and comparison with five other type IV collagen chains. J Biol Chem 1994, 269:13193-13199 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugimoto M, Oohashi T, Ninomiya Y: The genes COL4A5 and COL4A6, coding for basement membrane collagen chains α5(IV) and α6(IV), are located head-to-head in close proximity on human chromosome Xq22 and COL4A6 is transcribed from two alternative promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994, 91:11679-11683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antignac C, Knebelmann B, Drouot L, Gros F, Deschênes G, Hors-Cayla MC, Zhou J, Tryggvason K, Grünfeld JP, Broyer M, Gubler MC: Deletions in the COL4A5 collagen gene in X-linked Alport syndrome: characterization of the pathological transcripts in nonrenal cells and correlation with disease expression. J Clin Invest 1994, 93:1195-1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knebelmann B, Breillat C, Forestier L, Arondel C, Jacassier D, Giatras I, Drouot L, Deschênes G, Grünfeld JP, Broyer M, Gubler MC, Antignac C: Spectrum of mutations in the COL4A5 gene in X-linked Alport syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 1996, 59:1221-1232 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lemmink HH, Schroder CH, Monnens LAH, Smeets HJM: The clinical spectrum of type IV collagen mutations. Hum Mutat 1997, 9:477-499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Renieri A, Bruttini M, Galli L, Zanelli P, Neri T, Rossetti S, Turco A, Heiskari N, Zhou J, Gusmano R, Massella L, Banfi G, Scolari F, Sessa A, Rizzoni G, Tryggvason K, Pignatti PF, Savi M, Ballabio A, De Marchi M: X-linked Alport syndrome: an SSCP-based mutation survey over all 51 exons of the COL4A5 gene. Am J Hum Genet 1996, 58:1192-1204 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tryggvason K (Ed): Mutations in type IV collagen genes and Alport phenotypes. Contributions to Nephrology: Molecular Pathology and Genetics of Alport Syndrome, vol 117. Basel, Karger, 1996, pp 154–171 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Kawai S, Nomura S, Harano T, Harano K, Fukushima T, Osawa G, : the Japanese Alport Network: The COL4A5 gene in Japanese Alport syndrome patients. Spectrum of mutations in all exons. Kidney Int 1996, 49:814-822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boye E, Mollet G, Forestier L, Cohen-Solal L, Heidet L, Cochat P, Grünfeld JP, Palcoux JB, Gubler MC, Antignac C: Determination of the genomic structure of the COL4A4 gene and of novel mutations causing autosomal recessive Alport syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 1996, 63:1329-1340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plant KE, Green PM, Vetrie D, Flinter FD: Detection of mutations in COL4A5 in patients with Alport syndrome. Hum Mutat 1999, 13:124-132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heikkilä P, Soininen R: The type IV collagen gene family. Tryggvason K eds. Contributions to Nephrology: Molecular Pathology and Genetics of Alport Syndrome, 1996, vol 117.:pp 105-129 Karger, Basel [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou J, Reeders ST: The α chains of type IV collagen. Tryggvason K eds. Contributions to Nephrology: Molecular Pathology and Genetics of Alport Syndrome, 1996, vol 117.:pp 80-104 Karger, Basel [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butkowski RJ, Wieslander J, Kleppel M, Michael AF, Fish AJ: Basement membrane collagen distribution in the kidney: regional localization of novel chains related to collagen IV. Kidney Int 1989, 35:1195-1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ninomiya Y, Kagawa M, Iyama K, Naito I, Kishiro Y, Seyer JM, Sugimoto M, Oohashi T, Sado Y: Differential expression of two basement membrane collagen genes, COL4A6 and COL4A5, demonstrated by immunofluorescence staining using peptide-specific monoclonal antibodies. J Cell Biol 1994, 130:1219-1229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshioka K, Hino S, Takemura T, Maki S, Wieslander J, Takekoshi Y, Makino H, Kagawa M, Sado Y, Kashtan CE: Type IV collagen α5 chain. Normal distribution and abnormalities in X-linked Alport syndrome revealed by monoclonal antibodies. Am J Pathol 1994, 144:986-996 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peissel B, Geng L, Kalluri R, Kashtan C, Rennke HG, Gallo GR, Yoshioka K, Sun MJ, Hudson BG, Neilson EG, Zhou J: Comparative distribution of the α1(IV), α5(IV) and α6(IV) collagen chains in normal human adult and fetal tissues and in kidneys from X-linked Alport syndrome patients. J Clin Invest 1995, 96:1948-1957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalluri R, Shield CF, Todd P, Hudson BG, Neilson EG: Isoform switching of type IV collagen is developmentally arrested in X-linked Alport syndrome leading to increases susceptibility of renal basement membrane to endoproteolysis. J Clin Invest 1997, 99:2470-2478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gubler MC, Heidet L, Antignac C: Alport’s syndrome, thin basement membrane nephropathy and nail-patella syndrome. Heptinstall’s Pathology of the Kidney, ed 5. Edited by JC Jennette, JL Olson, MM Schwartz, FG Silva. Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1998, pp 1207–1230

- 28.Johansson C, Butkowski R, Wieslander J: The structural organization of type IV collagen. Identification of three NC1 populations in the glomerular basement membrane. J Biol Chem 1992, 267:24533-24537 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kleppel MM, Fan WW, Cheong HI, Michael AF: Evidence for separate networks of classical and novel basement membrane collagen: characterization of α3(IV)-Alport antigen heterodimer. J Biol Chem 1992, 267:4137-4142 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gunwar S, Ballester F, Noelken ME, Sado Y, Ninomiya Y, Hudson BG: Glomerular basement membrane. Identification of a novel disulfide-cross-linked network of alpha3, alpha4 and alpha5 chains of type IV collagen and its implication for the pathogenesis of Alport syndrome. J Biol Chem 1998, 273:8767-8775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kasai TZ, Enders GC, Gunwar S, Brunmark C, Wieslander J, Kalluri R, Zhou J, Noelken ME, Hudson BG: Seminiferous tubule basement membrane. Compositions and organization of type IV collagen chains, and the linkage of alpha3(IV) and alpha5(IV) chains. J Biol Chem 1997, 272:17023-17032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harvey SJ, Zheng K, Sado Y, Naito I, Ninomiya Y, Jacobs RM, Hudson BG, Thorner PS: Role of distinct type IV collagen networks in glomerular development and function. Kidney Int 1998, 54:1857-1866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng K, Thorner P, Marrano P, Baumal R, McInnes RR: Canine X chromosome-linked hereditary nephritis: a genetic model for X-linked hereditary nephritis resulting from a single base mutation in the gene encoding the α5 chain of collagen type IV. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994, 91:3989-3993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hood JC, Savige J, Hendtlass A, Kleppel MM, Huxtable CR, Robinson WF: Bull terrier hereditary nephritis: a model for autosomal dominant Alport syndrome. Kidney Int 1995, 47:758-765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miner JH, Sanes JR: Molecular and functional defects in kidneys of mice lacking collagen α3(IV): implications for Alport syndrome. J Cell Biol 1996, 135:1403-1413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cosgrove D, Meehan DT, Grunkemeyer JA, Kornak JM, Sayers R, Hunter WJ, Samuelson GC: Collagen COL4A3 knockout: a mouse model for autosomal Alport syndrome. Genes Dev 1996, 10:2981-2992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lees GE, Helman RG, Kashtan CE, Michael AF, Homco LD, Millichamp NJ, Ninomiya Y, Sado Y, Naito I, Kim Y: A model of autosomal recessive Alport syndrome in English cocker spaniel dogs. Kidney Int 1998, 54:706-719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kashtan CE, Kleppel MM, Gubler MC: Immunohistochemical findings in Alport syndrome. Tryggvason K eds. Contributions to Nephrology: Molecular Pathology and Genetics of Alport Syndrome, 1996, vol 117.:142-153 Karger, Basel [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gubler MC, Knebelmann B, Beziau A, Broyer M, Pirson Y, Haddoum F, Kleppel MM, Antignac C: Autosomal recessive Alport syndrome. Immunohistochemical study of type IV collagen chain distribution. Kidney Int 1995, 47:1142-1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mazzucco G, Barsotti P, Muda AO, Fortunato M, Mihatsch M, Torri-Tarelli L, Renieri A, Faraggiana T, De Marchi M, Monga G: Ultrastructural and immunohistochemical findings in Alport’s syndrome: a study of 108 patients from 97 Italian families with particular emphasis on COL4A5 gene mutation correlations. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998, 9:1023-1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naito I, Kawai S, Nomura S, Sado Y, Osawa G, : the Japanese Alport Network: Relationship between COL4A5 gene mutation and distribution of type IV collagen in male X-linked Alport syndrome. Kidney Int 1996, 50:304-311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakanishi K, Yoshikawa N, Iijima K, Kitagawa K, Nakamura H, Ito H, Yoshioka K, Kagawa M, Sado Y: Immunohistochemical study of α1–5 chains of type IV collagen in hereditary nephritis. Kidney Int 1994, 46:1413-1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kashtan C, Kim Y: Distribution of the α1 and α2 chains of collagen IV and of collagens V and VI in Alport syndrome. Kidney Int 1992, 42:115-126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pihlajaniemi T, Tryggvason K, Myers J, Kurkinen M, Lebo R, Cheung M, Prockop DJ, Boyd CD: cDNA clones for the pro-α1(IV) chain of human type IV procollagen reveal an unusual homology of amino acid sequences in two halves of the carboxyl-terminal domain. J Biol Chem 1985, 260:7681-7687 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mariyama M, Leinonen A, Mochizuki T, Tryggvason K, Reeders ST: Complete primary structure of the alpha 3(IV) collagen chain. Coexpression of the alpha3(IV) and alpha4(IV) collagen chains in human tissues. J Biol Chem 1994, 269:23013-23017 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leinonen A, Mariyama M, Mochizuki T, Tryggvason K, Reeders ST: Complete primary structure of the human type IV collagen alpha 4(IV) chain. Comparison with structure and expression of the other alpha(IV) chains. J Biol Chem 1994, 269:26172-26177 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou J, Hertz JM, Leinonen A, Tryggvason K: Complete amino acid sequence of the human a5(IV) collagen chain and identification of a single mutation in exon 23 converting glycine 521 in the collagenous domain to cysteine in an Alport syndrome patient. J Biol Chem 1992, 267:12475-12481 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heidet L, Cai Y, Sado Y, Ninomiya Y, Thorner P, Guicharnaud L, Boye E, Chauvet V, Cohen-Solal L, Beziau A, Garcia Torres R, Antignac C, Gubler MC: Diffuse leiomyomatosis associated with inherited Alport syndrome. Extracellular matrix study using immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization. Lab Invest 1997, 76:233–246 [PubMed]

- 49.Sibony M, Gasc JM, Soubrier F, Alhenc-Gelas F, Corvol P: Gene expression and tissue localization of the two isoforms of angiotensin I converting enzyme. Hypertension 1993, 21:827-835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tryggvason K, Heikkila P, Pettersson E, Tibell A, Thorner P: Can Alport syndrome be treated by gene therapy? Kidney Int 1997, 51:1493-1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laurie GW, Horikoshi S, Killen PD, Segui-Real B, Yamada Y: In situ hybridization reveals temporal and spatial changes in cellular expression of mRNA for a laminin receptor, laminin, and basement membrane (type IV) collagen in the developing kidney. J Cell Biol 1989, 109:1351-1362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee LK, Pollock AS, Lovett DH: Asymmetric origin of the mature glomerular basement membrane. J Cell Physiol 1993, 157:169-177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bergijk EC, van Alderwegen IE, Baelde HJ, de Heer E, Funabiki K, Miyai H, Killen PD, Kalluri RK, Bruijn JA: Differential expression of collagen IV isoforms in experimental glomerulosclerosis. J Pathol 1998, 184:307-315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Minto AW, Kalluri R, Togawa M, Bergilk EC, Killen PD, Salant DJ: Augmented expression of glomerular basement membrane specific type IV collagen isoforms (α3-α5) in experimental membranous nephropathy. Proc Assoc Am Physiol 1998, 3:207-217 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thorner PS, Zheng K, Kalluri R, Jacobs R, Hudson BG: Coordinate gene expression of the α3, α4, and α5 chains of collagen type IV: evidence from a canine model of X-linked nephritis with a COL4A5 gene mutation. J Biol Chem 1996, 271:13821-13828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prockop DJ: Mutations that alter the primary structure of type I collagen. The perils of a system for generating large structures by the principle of nucleated growth. J Biol Chem 1990, 265:15349–15352 [PubMed]

- 57.Chiodo AA, Sillence DO, Cole WG, Bateman JF: Abnormal type III collagen produced by an exon-17-skipping mutation of the COL3A1 gene in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV is not incorporated into the extracellular matrix. Biochem J 1995, 311:939-943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sakuntabhai A, Hammami-Hauasli N, Bodemer C, Rochat A, Prost C, Barrandon Y, de Prost Y, Lathrop M, Wojnarowska F, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Hovnanian A: Deletions within COL7A1 exons distant from consensus splice sites alter splicing and produce shortened polypeptides in dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Am J Hum Genet 1998, 63:737-743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hammami-Hauasli N, Schumann H, Raghunath M, Kilgus O, Luthi U, Luger T, Bruckner-Tuderman L: Some, but not all, glycine substitution mutations in COL7A1 result in intracellular accumulation of collagen VII, loss of anchoring fibrils, and skin blistering. J Biol Chem 1998, 1922, 273:8-34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nakanishi K, Yoshikawa N, Iijima K, Nakamura H: Expression of type IV collagen α3 and α4 chain mRNA in X-linked Alport syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 1996, 7:938-945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sasaki S, Zhou B, Fan WW, Kim Y, Barker DF, Denison JC, Atkin CL, Gregory MC, Zhou J, Segal Y, Sado Y, Ninomiya Y, Michael AF, Kashtan CE: Expression of mRNA for type IV collagen alpha1, alpha5 and alpha6 chains by cultured dermal fibroblasts from patients with X-linked Alport syndrome. Matrix Biol 1998, 17:436-444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zheng, K, Harvey S, Sado Y, Naito I, Ninomiya Y, Jacobs R, Thorner PS: Absence of the a6(IV) chain of collagen type IV in Alport syndrome is related to a failure at the protein assembly level and does not result in diffuse leiomyomatosis. Am J Pathol 1999, 154:1883–1891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Gupta MC, Graham PL, Kramer JM: Characterization of α1(IV) collagen mutations in Caenorhabditis elegans and the effects of α1(IV) and α2(IV) mutations on type IV collagen distribution. J Cell Biol 1997, 137:1185-1196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]