Abstract

Endocannabinoids are powerful modulators of synaptic transmission that act on presynaptic cannabinoid receptors. Cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) is the dominant receptor in the CNS, and is present in many brain regions, including sensory cortex. To investigate the potential role of CB1 receptors in cortical development, we examined the developmental expression of CB1 in rodent primary somatosensory (barrel) cortex, using immunohistochemistry with a CB1-specific antibody. We found that before postnatal day (P) 6, CB1 receptor staining was present exclusively in the cortical white matter, and that CB1 staining appeared in the grey matter between P6 and P20 in a specific laminar pattern. CB1 staining was confined to axons, and was most prominent in cortical layers 2/3, 5a, and 6. CB1 null (−/−) mice showed altered anatomical barrel maps in layer 4, with enlarged inter-barrel septa, but normal barrel size. These results indicate that CB1 receptors are present in early postnatal development and influence development of sensory maps.

Keywords: Cannabinoid, whisker, barrel, septa, axons, sensory map

The endocannabinoid (eCB) signaling system modulates synaptic transmission in many brain areas, including striatum, cerebellum, hippocampus, and neocortex (Chevaleyre et al., 2006). eCBs are lipids that are synthesized by postsynaptic neurons in response to depolarization, increases in intracellular calcium, and/or activation of specific metabotropic neurotransmitter receptors. eCBs diffuse retrogradely to activate cannabinoid receptors on presynaptic terminals, with the CB1 receptor being the primary cannabinoid receptor on presynaptic terminals in the brain (Piomelli et al., 1998; Wilson and Nicoll, 2001, 2002; Freund et al., 2003). CB1 receptors occur most prominently on inhibitory terminals (Marsicano and Lutz, 1999; Bodor et al., 2005), but also exist on excitatory terminals (Katona et al., 2006; Kawamura et al., 2006; Monory et al., 2006). CB1 receptor activation reduces presynaptic release probability (Brown et al., 2004), leading to short-term and long-term depression of excitatory and inhibitory transmission (Wilson and Nicoll, 2002; Chevaleyre et al., 2006). Such CB1-mediated synaptic plasticity is prominent in mature and adolescent neocortex (Sjostrom et al., 2003; Trettel and Levine, 2003; Trettel et al., 2004; Bodor et al., 2005; Bender et al., 2006b; Domenici et al., 2006).

While modulation of mature cortical synaptic transmission by eCB signaling is increasingly understood, less is known about the eCB system in cortical development. Cannabinoid ligands and CB1 receptors are present in many brain areas during development, including some areas that show transient, developmentally restricted CB1 expression (Fernandez-Ruiz et al., 2000; Fride, 2004). eCB signaling appears to significantly regulate some aspects of early brain development, including neurogenesis (Galve-Roperh et al., 2006), neuronal differentiation (Rueda et al., 2002), axon pathfinding (Gomez et al., 2003), and development of some transmitter systems (Fride, 2004). During early postnatal development, CB1 blockade can alter cortical activity patterns (Bernard et al., 2005), suggesting the potential to regulate activity-dependent synaptic refinement. However, a detailed understanding of the role of eCBs in cortical development is lacking.

As a first step in investigating the potential role of CB1 receptors in postnatal development of cerebral cortex, we studied CB1 receptor protein expression during postnatal development in rat and mouse somatosensory (S1) cortex, using immunohistochemical staining with a CB1-specific antibody. S1 cortex was chosen because of the detailed understanding of cortical microcircuits, postnatal development and plasticity in this area (Erzurumlu and Kind, 2001; Petersen, 2003; Feldman and Brecht, 2005). In the whisker region of S1, neurons in layer 4 are segregated into dense clusters called barrels, each of which receives lemniscal thalamocortical input corresponding to a single facial whisker. The barrels are arranged into an isomorphic whisker map (Woolsey and van der Loos, 1970). Barrels are separated by cell-sparse regions called septa, which receive extra-lemniscal input (Koralek et al., 1988; Lu and Lin, 1993; Kim and Ebner, 1999). We found that CB1 expression increased markedly from postnatal day (P) 4 to P16 in the whisker region of rat S1, with mature staining patterns attained by P16. CB1 staining was largely confined to axons, with highest levels in L2/3, L5a and L6. In L4, CB1 expression was most prevalent in septa. In CB1-deficient (CB1−/−) mice, septa were enlarged, but barrel size was unchanged. These results indicate that CB1 receptors are present during critical periods for activity-dependent synaptic refinement in S1, and suggest that CB1 receptors may play a role in development of S1 cortex.

Experimental Procedures

All procedures were approved by the UCSD Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. 14 Long-Evans rats (P4–P63; P0 was defined as the day of birth) (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) were used for developmental analysis of CB1 receptor expression. 7 adult CB1-deficient mice (either sex) in a predominant C57BL/6N background (chimeric C57BL/6N – 129 progenitors, backcrossed 5 generations into C57BL/6N; Marsicano et al., 2002) were used to assess CB1 staining and barrel map formation in CB1−/− animals. These mice were kindly provided by B. Lutz and G. Marsicano (Mainz, Germany). Mice were bred from heterozygote CB1+/− parents and genotyped by PCR to identify CB1−/− (n = 4) and CB1+/+ (n = 3) individuals prior to the experiments (Marsicano et al., 2002).

CB1 immunostaining

Animals were perfused transcardially with 1% lidocaine and 0.5% heparin in phosphate buffer (PB, 0.1 M, pH 7.4), followed by 4% paraformaldehyde and 2% sucrose in PB. Brains were removed and post-fixed for 2 hours in 4% paraformaldehyde and 20% sucrose in 0.1M PB 2° C, then transferred to 30% sucrose in PB overnight at 2° C.

Sections of the posteromedial barrel subfield of S1 cortex (40 μm thick) were cut 50° from the midsagittal plane (see Fig. 1E for plane of section) on a freezing microtome (American Optical 860). This plane of section is orthogonal to the cortical representation of the 5 rows of large facial whiskers (termed A–E), such that each section contains one barrel from each of the whisker rows (Finnerty et al., 1999; Bender et al., 2003). As a result, barrel boundaries and inter-barrel septa are readily observable, and A–E barrels can be specifically identified in the sections.

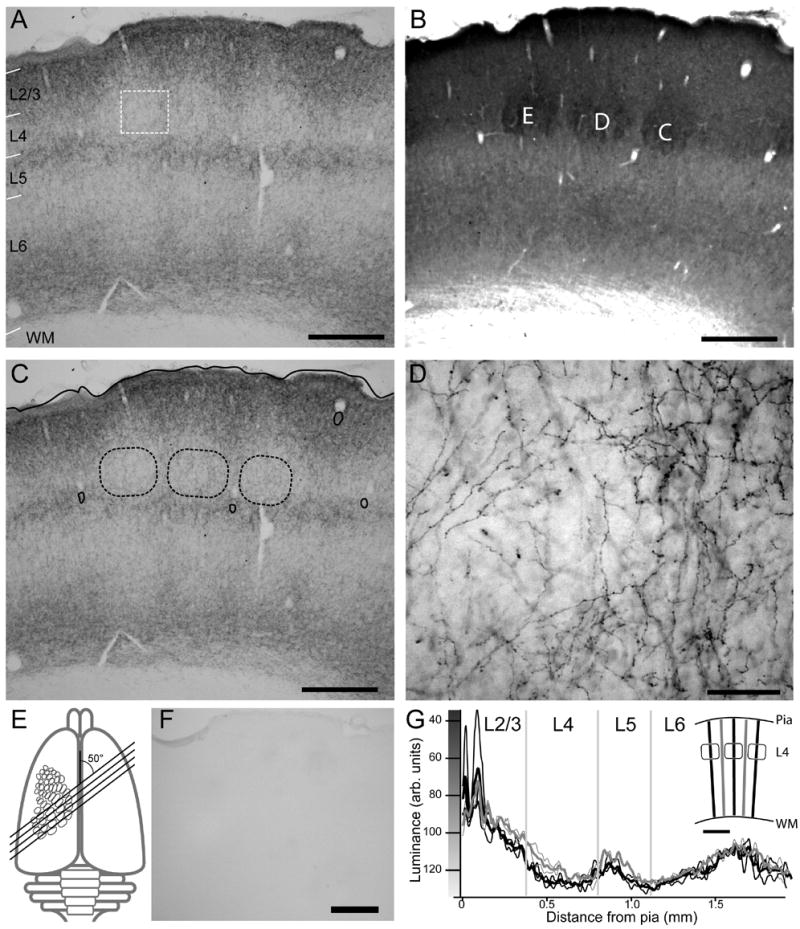

Figure 1.

CB1 immunoreactivity in mature (P40) rat barrel cortex. A, Low resolution brightfield image of CB1 staining in 50 micron-thick across-row S1 section. Layer boundaries were determined from neighboring CO-stained section in (B). WM, white matter. B, Neighboring cytochrome oxidase (CO)-stained section, showing barrels from whisker rows C, D and E. C, Same image as A, with barrel boundaries (dashed) projected from panel B. Solid contours are pia and blood vessels used for alignment. Scale in A–C: 500 μm. D, High power brightfield image of area in A marked with white rectangle. Scale: 50 μm. E, Schematic of rodent brain depicting across-row section angle. Relative size of S1 map was expanded to allow visualization. F. Section reacted in parallel without primary antibody. Scale: 500 μm. G. Quantification of CB1 staining intensity for section shown in A. Thin black traces, staining intensity along individual barrel-related transects. Thin grey traces, staining along septa-related transects. Thick traces show averages of individual transects. Locations of transects are shown in the inset. Grey vertical lines indicate layer boundaries, as determined from neighboring CO-stained section.

Alternate sections were stained with anti-CB1 antibody, or for cytochrome oxidase (CO) activity to visualize barrels and layer boundaries (Wong-Riley, 1979; Fox, 1992). CB1 immunostaining was performed as follows: Sections were treated with 0.5% hydrogen peroxide and 10% methanol in PB to quench endogenous peroxidases, and then incubated in blocking solution (20% normal goat serum, 5% sucrose, and 0.05% Triton-X 100 in PB) at room temperature for 2 hours. Sections were transferred to a primary antibody solution containing anti-CB1 antibody (L15 antibody, 1:500 for rat, 1:2000 for mouse) and 0.05% sodium azide in blocking solution, continuously agitated for 48 hrs at room temperature. Sections were washed in tris-buffered saline (TBS: 0.05M Tris base, 0.9% NaCl, pH: 7.4), and then placed in blocking solution (20% normal goat serum and 5% sucrose in TBS) for 2 hours, incubated for 2 hr in secondary antibody (biotinylated goat anti-rabbit, 1:200 at room temperature), and then treated with an avidin-biotin reaction (2 hrs, Vector). Peroxidases were visualized with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Sigma), intensified with cobalt and nickel (0.1% DAB, 0.005% CoCl2, 0.25% Ni(NH4)2(SO4)2). Sections were mounted from 0.3% gelatin in TBS onto Superfrost slides (Fisher), air dried 2–3 hrs, dehydrated in ascending ethanols, defatted with xylenes, and coverslipped in Permount.

The L15 anti-CB1 antibody used in this study was raised in rabbits against the last 15 C-terminal animo acid residues of the rat CB1 receptor. In previous studies, this antibody was shown to specifically recognize rat CB1 protein by western blot, and to specifically label cells transfected with the CB1 receptor (Bodor et al., 2005).

For comparison of staining across ages, sections of animals from each age (P4–P63) were run in parallel, using the same antibody and DAB solutions, in order to enable comparison of staining intensity across development.

Analysis of CB1 laminar staining

CB1-stained sections were digitally photographed on an Axioskop 2 plus microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) using a 4x objective and a Magnafire camera (Optronics, Goleta, CA). Image resolution was 2.66 μm/pixel. When comparing staining across ages (e.g., Figs. 2 and 3), photographs of all ages were made in a single session with illumination and exposure settings held constant across sections. Images were contrast-enhanced with a uniform, globally applied algorithm across all sections (Adobe Photoshop, Levels Function, input levels of 75–150 [which represented the dynamic range of camera output] were linearly mapped to output levels of 0–255). This algorithm, which was performed identically across all ages, was done to improve visualization of staining patterns.

Figure 2.

Representative CB1 immunoreactivity in S1 at different postnatal ages. Layer boundaries were determined from neighboring CO-stained sections (not shown). All sections in this image were stained and photographed in parallel to allow comparison of staining intensity across age. WM, white matter. Scale: 500 μm.

Figure 3.

Quantification of CB1 staining luminance as a function of depth below the pia. Lower numbers represent darker staining. Black, barrel-centered transects. Grey, septa-centered transects from the same sections. Bars show mean ± SEM, with each section counted as a single sample (see Experimental Procedures). N indicates number of sections. Light grey rectangles indicate mean depths corresponding to L4 and L5b, as determined by CO staining.

To determine barrel location and laminar boundaries in CB1-stained sections, barrels and laminar boundaries were traced from neighboring CO-stained sections using Neurolucida software (Microbrightfield, Williston, VT). These features were projected on CB1-stained sections in Neurolucida using blood vessel and pial landmarks for alignment. The quantitative laminar pattern of CB1 staining was determined by measuring luminance of CB1 staining along transects, 19 pixels (50 μm) wide, extending radially from the pia to the white matter, using Scion Image software (Scion Corporation, Frederick, Maryland). Transects were positioned to pass through barrel centers (defined by centroid of CO-stained barrel) or septal centers (defined as the midpoint between walls of two neighboring barrels). Luminance was averaged across all 19 pixels of the transect at a given depth relative to the pia, and then smoothed across depth using a 7 pixel box filter. Typically, 3 barrel-related transects and 2 septa-related transects were analyzed per section, and results were averaged to generate a single mean barrel-related and a single mean septal-related luminance profile per section. Barrel- and septal-related luminance profiles were then averaged across all sections for each age, with each section counted as a single sample for statistical analysis. L3–L4, L4–L5, and L5–L6 border boundaries are directly visible in CO-stained sections. Position of the L5a–L5b border was estimated at 40% of the depth through L5, as determined by analysis of adjacent Nissl- and CO-stained sections at these ages (D.E.F., unpublished data).

Comparison of cytochrome oxidase barrel maps in CB1+/+ and CB1−/− mice

To measure barrel maps, mice were perfused, as described above. After post-fixing the brain, cortical blocks containing S1 cortex were gently flattened between microscope slides, fixed for an additional 24–48 hrs in 4% paraformaldehyde and 30% sucrose in PB, and sectioned tangentially (i.e., parallel to the pia) at 50 μm. Sections were stained for cytochrome oxidase as described above. Barrels were traced from CO-stained sections and barrel maps were reconstructed across sections using Neurolucida software. Map reconstructions and morphological analysis were done blind to genotype. Barrel centroids were calculated using Neuroexplorer software (Microbrightfield, Williston, VT), and barrel and septal width were measured along line segments connecting centroids of adjacent barrels.

Results

To examine how CB1 receptor expression develops in rat S1 cortex, we stained for CB1 receptor protein in the posteromedial barrel subfield of rat S1, which is the portion of S1 that contains barrels representing the large facial whiskers. Sections were cut at an oblique angle that contains one barrel from each of the 5 rows on the face, termed A–E (Fig. 1E). Alternate sections were stained for CB1 protein using a specific anti-CB1 antibody (Bodor et al., 2005) (Fig. 1A), and for cytochrome oxidase activity, to label laminar boundaries and barrels in cortical layer 4 (Fig. 1B) (Wong-Riley and Welt, 1980). Projecting these features onto neighboring CB1-stained sections allowed us to characterize CB1 staining patterns relative to laminar boundaries and barrel-related columns in S1 (Fig. 1C).

CB1 antibody staining had a characteristic laminar pattern (Fig. 1A-C). Axons were strongly stained, with dense labeling of varicosities presumed to be synaptic boutons (Fig. 1D). This staining pattern is consistent with results in human and monkey cortex (Eggan and Lewis, 2006), and in a previous study of adult rat S1 (Bodor et al., 2005). The specificity of this staining pattern was assessed by omitting primary antibody in a subset of reactions. In these reactions, no axonal staining was observed (Fig. 1F).

The laminar pattern of antibody staining was analyzed quantitatively by measuring luminance of CB1 staining in radial transects, 50 μm wide, that extended from the pia to the white matter, orthogonal to the curvature of the barrels in layer (L) 4. Transects were positioned to pass through either the center of L4 barrels (Fig. 1G, insert, black lines) or the center of inter-barrel septa (grey lines). Mean luminance was calculated at each depth below the pia and smoothed over depth with an 18-μm box filter. Low luminance values, plotted upward in the figures, indicate dark staining. This analysis confirmed the visual impression that CB1 staining was darkest in supragranular layers, particularly upper L2/3. In L4, staining was sparse in barrel regions, but somewhat stronger in septal regions of L4 between the barrels. Dense staining was found in L5a, just below the barrels, and just above the white matter in L6. Between, in L5b and upper L6, staining was typically low, comparable to that found in L4 barrels (Fig. 1G).

CB1 immunoreactivity through development

To examine the development of CB1 receptor staining, we perfused Long-Evans rats at each of the following ages: P4, P6, P8, P12, P16, P20, P40 and P63. Two separate litters were analyzed. Within each litter, one animal at each age was tested, with sections from all animals being run in parallel, in the same solutions, to allow direct comparison of staining intensity across ages. The two litters were run in two separate immunohistochemical reactions. Figures 2 and 3 show the results of the first litter. The second litter yielded somewhat fainter staining, but with a similar developmental progression of staining across age.

At the earliest ages (P4–P8), transient CB1 staining was found in the white matter below L6 (Fig. 2). This is consistent with previous studies showing cannabinoid receptor expression in white matter tracts, including cortical white matter, during early development (Romero et al., 1997; Berrendero et al., 1998; Fernandez-Ruiz et al., 2000). White matter staining disappeared by P12.

CB1 staining in the cortical grey matter developed differently (Fig. 2). CB1 expression was faint at P4, and then developed in two distinct phases. First, immunoreactivity developed in L2/3 and L6, becoming quite intense by P12. Second, between P12 and P16, CB1 staining increased in L5a (the upper sublamina of layer 5), and in L4 septa. This pattern of staining remained stable through P63. This staining pattern matched that previously reported in adult Wistar rats (Bodor et al., 2005), suggesting it represents the mature pattern of CB1 staining in S1 cortex.

To quantitatively analyze the laminar distribution of CB1 reactivity, radial transects of staining intensity were made for multiple (2 or 3) barrel- and septa-related columns in each section, as described above. Within a section, results from each transect were averaged to generate a single mean barrel-related luminance profile, and a single mean septal-related luminance profile, per section. Mean staining profiles across sections were then compared at each age (Fig. 3). In this analysis, each section represents one sample. Analysis was restricted to ages ≥ P8 due to the faint CB1 staining at P4 and P6. Results confirmed the visual impression that staining in superficial L2/3 and L6 increases by P12, followed by an increase in staining in L5a beginning at P16–20. In addition, this analysis confirmed that in L4 and lower L2/3, CB1 staining was greater in septa-related columns than in barrel-related columns at P16, P40 and P63 (Fig. 3). Thus, CB1-positive axons are preferentially found in L4 septa, relative to L4 barrels in mature S1. In other cortical layers, CB1 staining was equivalent between barrel- and septa-related columns.

Confirmation of CB1 antibody specificity using CB1 null mice

To confirm that CB1 antibody staining was specific for CB1 protein, we measured CB1 staining in adult CB1 null mice (>60 days of age) (Marsicano et al., 2002). Sections were made in the across-row plane, as in rats. In wild type mice (CB1+/+, n = 2), CB1 expression was similar to rat, with highest levels in L2/3, upper L5 (presumptive L5a), and lower L6 (Fig. 4, top). The L5–L6 border was not determined precisely in these sections. In CB1−/− littermates (n = 2), all specific staining of axons was absent (Fig. 4, bottom). Very faint residual staining persisted in the pia, and in scattered nuclei within the cortex (Fig. 4, bottom). This was regarded as non-specific staining, and did not occur within axons. These results are consistent with prior studies showing lack of staining in CB1−/− mice using this antibody (Bodor et al., 2005). Thus, we conclude that axonal staining by the anti-CB1 antibody represents specific detection of CB1 protein.

Figure 4.

CB1 immunoreactivity in S1 in one wild type and one CB1 null mouse. Layer boundaries were determined from neighboring CO-stained sections (not shown). Scale: 500 μm.

Effects of CB1 deletion on barrel map formation

Finally, we sought to determine if CB1 receptor expression influences barrel map development, utilizing CB1−/− mice. We visualized barrel maps using cytochrome oxidase staining in tangential, flattened sections through L4 (Fig. 5A) (Fox, 1992). Staining was performed in adult wild type mice (CB1+/+, n = 2 mice, 4 hemispheres) and CB1−/− littermates (n = 3 mice, 6 hemispheres). Barrel maps were reconstructed from CO-stained sections and quantitatively analyzed blind to genotype. Barrel maps were present in both CB1+/+ and CB1−/− mice, but the details of map organization differed subtly between genotypes (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Tangential distribution of large whisker barrels in S1 of mature wild type (CB1+/+) and CB1 knockout (CB1−/−) mice. A: Montage of cytochrome oxidase stain of L4 barrels in one CB1−/−mouse. R, rostral. C, caudal. L, lateral. M, medial. B, Reconstruction of barrel boundaries for the case in (A). Point show centroids of C2, C3, C4, D3, and E3 barrels. Barrel and septal dimensions were measured along lines connecting centroids. C. Barrel maps from CB1+/+ and CB1−/− mice. Scale in A–C: 500 μm. D, Barrel width along the arc dimension, for barrels D1–D4. Bars are mean ± SEM. E, Width of septa between D and E barrels, for arc 1–4. Bars are mean ± SEM. Asterisks, p < 0.05

To examine the spatial organization of the barrel maps, we measured the size of barrels and septa, focusing attention on whisker arcs 1–4 and rows C–E. Septal size was measured along line segments connecting the centroids of neighboring barrels (Fig. 5B). In CB1−/− mice, the size of septa between whisker rows D and E was larger than in CB1+/+ mice, for arc 1 (CB1+/+: 33.3 ± 6.8 μm, CB1−/−: 102.0 ± 16.1 μm; p < 0.01), arc 2 (CB1+/+: 38.5 ± 10.3 μm, CB1−/−: 106.7 ± 10.0 μm; p < 0.01), and arc 3 (CB1+/+: 33.2 ± 9.3 μm, CB1−/−: 78.5 ± 13.3 μm; p < 0.05), but not arc 4 (CB1+/+: 77.9 ± 6.4 μm, CB1−/−: 65.0 ± 16.1 μm; p > 0.5) (Fig. 5C, E). Septal size between C3 and D3 barrels was also larger in CB1−/− vs. CB1+/+ mice (CB1+/+: 65.0 ± 5.8 μm, CB1−/−: 108.9 ± 8.6 μm; p < 0.01).

In contrast, septal size within a row was not altered in CB1−/− mice (eg., septal width between D1 and D2, CB1+/+: 26.0 ± 3.0 μm, CB1−/−: 30.0 ± 4.1 μm; p = 0.5). There were no differences in the width of D-row barrels along arcs (eg., D2 CB1+/+: 270.7 ± 12.3 μm, D2 CB1−/−: 274.8 ± 15.1 μm; p = 0.9) or rows (eg., D2 CB1+/+: 176.5 ± 6.3 μm, D2 CB1−/−: 174.0 ± 10.7 μm, p = 0.87). These results demonstrate that the precise topography of barrel maps is altered in CB1−/− mice, suggesting that CB1 receptors play a role in modulating septal vs. barrel components of the L4 map.

Discussion

Developmental pattern of CB1 staining

These results reveal that CB1 receptor expression in S1 cortex develops postnatally in a specific temporal and laminar pattern in Long-Evans rats. The earliest staining (observed at P4) is prominent staining in the cortical white matter. This finding is consistent with previous reports using cannabinoid agonist binding and in situ labeling of CB1 mRNA, which also revealed early CB1 receptor expression in white matter tracts (Romero et al., 1997; Berrendero et al., 1998). This expression may represent CB1 protein in actively extending axons, including protein being trafficked to developing terminals (Fernandez-Ruiz et al., 2000). White matter staining begins to decrease at ~ P6, and is absent by P12.

In this rat strain, CB1 staining first appears in the cortical gray matter within L2/3 and L6, at around P6, which is after L4 barrels have formed (Keller, 1995). At P16, staining develops just below L4 barrels in L5a, as well as in L4 septa. L4 barrels remain largely devoid of staining at all ages. Thus, P6–16 marks a period of rapidly increasing staining intensity within L2/3, L4 septa, L5a, and L6. This is a period of rapid synaptogenesis and development of intracortical connections in S1 (Micheva and Beaulieu, 1996; Miller et al., 2001; Bender et al., 2003). This period also corresponds to the development of robust, adult-like sensory responses in some layers (Stern et al., 2001). The CB1 staining pattern visible at P16 remained stable until P63, suggesting that it represents the stable adult pattern. This mature pattern is consistent with a prior study of CB1 expression in adult rats (Bodor et al., 2005).

What cellular elements are represented by the CB1 staining?

A previous study found, using immunoelectron microscopy labeling of CB1 receptors, that CB1 receptors in S1 are found primarily on axon terminals from a subset of CCK-positive and calbindin-positive GABAergic interneurons (Bodor et al., 2005). Localization to GABAergic terminals is consistent with known physiological effects of CB1 receptors on GABA release, including depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition, DSI, which occurs in hippocampus, cerebellum, and neocortex (Chevaleyre et al., 2006). However, CB1 receptors also modulate excitatory transmitter release in S1 and other brain areas (Bender et al., 2006b; Chevaleyre et al., 2006). A recent study quantitatively examined CB1 receptor expression in inhibitory versus excitatory terminals using immunoelectron microscopy, and found that in hippocampus and cerebellar cortex, CB1 receptor expression was 10–20 fold higher in inhibitory terminals than in excitatory terminals (Kawamura et al., 2006). Given that the relatively low sensitivity of immunohistochemistry would make detection of CB1 staining in excitatory terminals unlikely, we conclude that the large majority of axonal staining we observed is likely to reflect staining within inhibitory terminals and axons. Thus, the developmental pattern of CB1 expression reported here is likely to reflect development of CB1-expressing inhibitory, rather than excitatory, circuits.

Effect of CB1 deletion on barrel maps

Unconditional deletion of the CB1 receptor in CB1−/− mice resulted in altered size of inter-barrel septa and spacing of barrels. This result indicates that the CB1 receptor plays a role, albeit a subtle one, in barrel map development. How CB1 receptors control formation of septa is unknown but could involve potential direct effects on septal neurons, glia, or afferents, or indirect effects on transmitter systems such as serotonin that are known to regulate barrel map formation (Erzurumlu and Kind, 2001). Because CB1 staining is largely absent in L4 before P4, when barrel and septal structure emerges, another possibility is that CB1 receptors expressed on early neurons or progenitors influence proliferation, differentiation, or migration of neurons or glia that form the septa (Fernandez-Ruiz et al., 1999). Finally, CB1 receptors may be required for the experience-dependent regulation of septal size that occurs throughout life (Polley et al., 2004). Because septal neurons integrate information across whiskers differently than barrel neurons (Kim and Ebner, 1999; Brecht and Sakmann, 2002), we speculate that the enlarged septa in CB1−/− mice may lead to abnormal processing of complex, dynamic multi-whisker input.

Possible functions of CB1 receptors in cortical development

The results shown here indicate that CB1 receptors are present during early development of somatosensory cortex, and function, in part, to regulate the precise topography of the whisker barrel map. CB1 receptors are strongly implicated in rapid synaptic plasticity, both of inhibitory synapses (DSI and long-term depression of inhibitory transmission) and excitatory synapses (transient, depolarization-induced suppression of excitation [DSE] and long-term depression of excitatory transmission) (Chevaleyre et al., 2006). Thus, CB1 receptors may contribute to late, activity-dependent cortical development, either by regulating sensory and spontaneous activity (Patel et al., 2002), or by directly mediating certain forms of experience-dependent synaptic plasticity. For example, long-term depression at excitatory L4–L2/3 synapses in S1 cortex requires CB1 receptors (Bender et al., 2006b). Whisker deprivation has been proposed to induce LTD at these synapses in vivo, which may drive Hebbian weakening of deprived whisker responses within the whisker map (Feldman and Brecht, 2005; Bender et al., 2006a). Thus, CB1 receptors may be involved in this component of developmental map plasticity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH R01 NS046652 to D.E.F.

List of Abbreviations

- CB1

Cannabinoid receptor type 1

- CO

Cytochrome oxidase

- DAB

Diaminobenzidine

- DSE

Depolarization-induced suppression of excitation

- DSI

Depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition

- eCB

Endocannabinoid

- L

Cortical layer

- LTD

Long-term synaptic depression

- P

Postnatal day

- PB

Phosphate buffer

- S1

Primary somatosensory cortex

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- WM

White matter

Footnotes

Section Editor: Chip Gerfen, Neuroanatomy.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bender KJ, Rangel J, Feldman DE. Development of columnar topography in the excitatory layer 4 to layer 2/3 projection in rat barrel cortex. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8759–8770. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-25-08759.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender KJ, Allen CB, Bender VA, Feldman DE. Synaptic basis for whisker deprivation-induced synaptic depression in rat somatosensory cortex. J Neurosci. 2006a;26:4155–4165. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0175-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender VA, Bender KJ, Brasier DJ, Feldman DE. Two coincidence detectors for spike timing-dependent plasticity in somatosensory cortex. J Neurosci. 2006b;26:4166–4177. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0176-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard C, Milh M, Morozov YM, Ben-Ari Y, Freund TF, Gozlan H. Altering cannabinoid signaling during development disrupts neuronal activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9388–9393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409641102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrendero F, Garcia-Gil L, Hernandez ML, Romero J, Cebeira M, de Miguel R, Ramos JA, Fernandez-Ruiz JJ. Localization of mRNA expression and activation of signal transduction mechanisms for cannabinoid receptor in rat brain during fetal development. Development. 1998;125:3179–3188. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.16.3179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodor AL, Katona I, Nyiri G, Mackie K, Ledent C, Hajos N, Freund TF. Endocannabinoid signaling in rat somatosensory cortex: laminar differences and involvement of specific interneuron types. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6845–6856. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0442-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SP, Safo PK, Regehr WG. Endocannabinoids inhibit transmission at granule cell to Purkinje cell synapses by modulating three types of presynaptic calcium channels. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5623–5631. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0918-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevaleyre V, Takahashi KA, Castillo PE. Endocannabinoid-mediated synaptic plasticity in the CNS. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:37–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domenici MR, Azad SC, Marsicano G, Schierloh A, Wotjak CT, Dodt HU, Zieglgansberger W, Lutz B, Rammes G. Cannabinoid receptor type 1 located on presynaptic terminals of principal neurons in the forebrain controls glutamatergic synaptic transmission. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5794–5799. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0372-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggan SM, Lewis DA. Immunocytochemical Distribution of the Cannabinoid CB1 Receptor in the Primate Neocortex: A Regional and Laminar Analysis. Cereb Cortex. 2006 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erzurumlu RS, Kind PC. Neural activity: sculptor of 'barrels' in the neocortex. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:589–595. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01958-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman DE, Brecht M. Map Plasticity in Somatosensory Cortex. Science. 2005 doi: 10.1126/science.1115807. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Ruiz J, Berrendero F, Hernandez ML, Ramos JA. The endogenous cannabinoid system and brain development. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:14–20. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01491-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Ruiz JJ, Berrendero F, Hernandez ML, Romero J, Ramos JA. Role of endocannabinoids in brain development. Life Sci. 1999;65:725–736. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00295-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnerty GT, Roberts LS, Connors BW. Sensory experience modifies the short-term dynamics of neocortical synapses. Nature. 1999;400:367–371. doi: 10.1038/22553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox K. A critical period for experience-dependent synaptic plasticity in rat barrel cortex. J Neurosci. 1992;12:1826–1838. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-05-01826.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund TF, Katona I, Piomelli D. Role of endogenous cannabinoids in synaptic signaling. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:1017–1066. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00004.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fride E. The endocannabinoid-CB(1) receptor system in pre- and postnatal life. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;500:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galve-Roperh I, Aguado T, Rueda D, Velasco G, Guzman M. Endocannabinoids: a new family of lipid mediators involved in the regulation of neural cell development. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:2319–2325. doi: 10.2174/138161206777585139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gary-Bobo M, Elachouri G, Scatton B, Le Fur G, Oury-Donat F, Bensaid M. The cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant (SR141716) inhibits cell proliferation and increases markers of adipocyte maturation in cultured mouse 3T3 F442A preadipocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:471–478. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.015040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez M, Hernandez M, Johansson B, de Miguel R, Ramos JA, Fernandez-Ruiz J. Prenatal cannabinoid and gene expression for neural adhesion molecule L1 in the fetal rat brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2003;147:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajos N, Katona I, Naiem SS, MacKie K, Ledent C, Mody I, Freund TF. Cannabinoids inhibit hippocampal GABAergic transmission and network oscillations. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:3239–3249. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona I, Rancz EA, Acsady L, Ledent C, Mackie K, Hajos N, Freund TF. Distribution of CB1 cannabinoid receptors in the amygdala and their role in the control of GABAergic transmission. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9506–9518. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09506.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona I, Urban GM, Wallace M, Ledent C, Jung KM, Piomelli D, Mackie K, Freund TF. Molecular composition of the endocannabinoid system at glutamatergic synapses. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5628–5637. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0309-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura Y, Fukaya M, Maejima T, Yoshida T, Miura E, Watanabe M, Ohno-Shosaku T, Kano M. The CB1 cannabinoid receptor is the major cannabinoid receptor at excitatory presynaptic sites in the hippocampus and cerebellum. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2991–3001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4872-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller A. Synaptic organization of the barrel cortex. In: Jones EG, Diamond IT, editors. The barrel cortex of rodents. New York: Plenum; 1995. pp. 221–262. [Google Scholar]

- Koralek K-A, Jensen KF, Killackey HP. Evidence for two complementary patterns of thalamic input to the rat somatosensory cortex. Brain Res. 1988;463:346–351. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90408-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim U, Ebner FF. Barrels and septa: separate circuits in rat barrels field cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1999;408:489–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu SM, Lin RC. Thalamic afferents of the rat barrel cortex: a light- and electron-microscopic study using Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin as an anterograde tracer. Somatosens Mot Res. 1993;10:1–16. doi: 10.3109/08990229309028819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsicano G, Lutz B. Expression of the cannabinoid receptor CB1 in distinct neuronal subpopulations in the adult mouse forebrain. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:4213–4225. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsicano G, Wotjak CT, Azad SC, Bisogno T, Rammes G, Cascio MG, Hermann H, Tang J, Hofmann C, Zieglgansberger W, Di Marzo V, Lutz B. The endogenous cannabinoid system controls extinction of aversive memories. Nature. 2002;418:530–534. doi: 10.1038/nature00839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheva KD, Beaulieu C. Quantitative aspects of synaptogenesis in the rat barrel field cortex with special reference to GABA circuitry. J Comp Neurol. 1996;373:340–354. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960923)373:3<340::AID-CNE3>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller B, Blake NM, Erinjeri JP, Reistad CE, Sexton T, Admire P, Woolsey TA. Postnatal growth of intrinsic connections in mouse barrel cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2001;436:17–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monory K, Massa F, Egertova M, Eder M, Blaudzun H, Westenbroek R, Kelsch W, Jacob W, Marsch R, Ekker M, Long J, Rubenstein JL, Goebbels S, Nave KA, During M, Klugmann M, Wolfel B, Dodt HU, Zieglgansberger W, Wotjak CT, Mackie K, Elphick MR, Marsicano G, Lutz B. The endocannabinoid system controls key epileptogenic circuits in the hippocampus. Neuron. 2006;51:455–466. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Gerrits R, Muthian S, Greene AS, Hillard CJ. The CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716 enhances stimulus-induced activation of the primary somatosensory cortex of the rat. Neurosci Lett. 2002;335:95–98. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen CC. The barrel cortex--integrating molecular, cellular and systems physiology. Pflugers Arch. 2003;447:126–134. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1167-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piomelli D, Beltramo M, Giuffrida A, Stella N. Endogenous cannabinoid signaling. Neurobiol Dis. 1998;5:462–473. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polley DB, Kvasnak E, Frostig RD. Naturalistic experience transforms sensory maps in the adult cortex of caged animals. Nature. 2004;429:67–71. doi: 10.1038/nature02469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero J, Garcia-Palomero E, Berrendero F, Garcia-Gil L, Hernandez ML, Ramos JA, Fernandez-Ruiz JJ. Atypical location of cannabinoid receptors in white matter areas during rat brain development. Synapse. 1997;26:317–323. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199707)26:3<317::AID-SYN12>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda D, Navarro B, Martinez-Serrano A, Guzman M, Galve-Roperh I. The endocannabinoid anandamide inhibits neuronal progenitor cell differentiation through attenuation of the Rap1/B-Raf/ERK pathway. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46645–46650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206590200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjostrom PJ, Turrigiano GG, Nelson SB. Neocortical LTD via coincident activation of presynaptic NMDA and cannabinoid receptors. Neuron. 2003;39:641–654. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00476-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern EA, Maravall M, Svoboda K. Rapid development and plasticity of layer 2/3 maps in rat barrel cortex in vivo. Neuron. 2001;31:305–315. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00360-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trettel J, Levine ES. Endocannabinoids mediate rapid retrograde signaling at interneuron right-arrow pyramidal neuron synapses of the neocortex. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:2334–2338. doi: 10.1152/jn.01037.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trettel J, Fortin DA, Levine ES. Endocannabinoid signalling selectively targets perisomatic inhibitory inputs to pyramidal neurones in juvenile mouse neocortex. J Physiol. 2004;556:95–107. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.058198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RI, Nicoll RA. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signalling at hippocampal synapses. Nature. 2001;410:588–592. doi: 10.1038/35069076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RI, Nicoll RA. Endocannabinoid signaling in the brain. Science. 2002;296:678–682. doi: 10.1126/science.1063545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong-Riley M. Changes in the visual system of monocularly sutured or enucleated cats demonstrable with cytochrome oxidase histochemistry. Brain Res. 1979;171:11–28. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90728-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong-Riley MT, Welt C. Histochemical changes in cytochrome oxidase of cortical barrels after vibrissal removal in neonatal and adult mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:2333–2337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.4.2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolsey TA, Van der Loos H. The structural organization of layer IV in the somatosensory region (SI) of mouse cerebral cortex. The description of a cortical field composed of discrete cytoarchitectonic units. Brain Res. 1970;17:205–42. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(70)90079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]