Abstract

The rectal mucosa, a region involved in human immunodeficiency virus/simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection and transmission, contains immune inductive sites, rectal lymphoid nodules (RLN), and effector sites, the lamina propria (LP). This study was designed to evaluate cell populations involved in rectal mucosal immune function in both RLN and LP, by immunocytochemical analysis of rectal mucosa from 11 SIV-infected (2 to 21 months postinfection) and five naive rhesus macaques. In the rectum, as previously observed in other intestinal regions, CD4+ cells were dramatically reduced in the LP of SIV-infected macaques, but high numbers of CD4+ cells remained in RLN indicating maintenance of T cell help in inductive sites. Cells expressing the mucosal homing receptor α4β7 were dramatically decreased in the RLN and LP of most SIV-infected macaques. The RLN of both naive and SIV-infected macaques contained high numbers of CD68 + MHC-II+ macrophages and cells expressing the co-stimulatory molecules B7-2 and CD40, as well as IgM + MHCII+ and IgM + CD40+ B cells, indicating maintenance of antigen presentation capacity. The LP of all three macaques SIV-infected for 2 months contained many B7-2+ cells, suggesting increased activation of antigen-presenting cells. LP of SIV-infected rectal mucosa contained increased numbers of IgM+ cells, confirming previous observations in small intestine and colon. The data suggest that antigen-presentation capacity is maintained in inductive sites of SIV-infected rectal mucosa, but immune effector functions may be altered.

The mucosa of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is rich in cells of the immune system including activated T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells which are targets of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and simian intestinal virus (SIV). Indeed, the GI mucosa is actively involved in HIV/SIV infection; 1,2 viral presence has been documented in the mucosa of the small intestine and colon of HIV-infected individuals 3,4 and SIV-infected macaques. 5-7 The prevalence of opportunistic intestinal infections in HIV/SIV-infected individuals 8,9 could be because of impairment of mucosal immune responses or to other effects of local viral replication in the intestinal mucosa. The intestinal mucosa is depleted of CD4+ T cells very early after intravenous inoculation with SIV, and this occurs long before CD4 T cell depletion is detected in blood, lymph nodes, or spleen. 10,11 These results, which have been independently confirmed, 12,13 entailed quantitation of cells in the duodenum, jejunum, and colon but did not include the rectal mucosa.

The rectal mucosa is of particular importance in HIV/SIV infection and transmission for several reasons. It is rich in lymphoid aggregates and follicles which have been shown to be sites of viral replication in HIV-infected patients. 4 Viral production in the rectal mucosa has been implicated in transmission of HIV from infected hosts to uninfected individuals. 14 The rectal mucosa offers a relatively convenient site for sampling of the GI mucosa in humans. In addition, the rectal mucosa is a site of initial HIV/SIV entry. 7,15,16 Administration of antigens via the rectum of humans results in local and systemic immune responses, 17,18 making the rectal mucosa an important candidate route for delivery of HIV/SIV vaccines. The cell populations responsible for induction of local immune responses in the organized lymphoid tissues of the small intestine (ie, the Peyer’s patches) have been studied in some detail, 19,20 but much less is known about the lymphoid tissues of the rectum.

We therefore undertook an immunocytochemical study of the rectal mucosa in normal and SIV-infected rhesus macaques to investigate possible alterations in the cellpopulations responsible for mucosal immune function. In the intestinal mucosa, the inductive and effector arms of the immune system are anatomically distinct. Inductive sites consist of organized lymphoid tissue, seen in the rectum as isolated rectal lymphoid nodules (RLN), whereas effector sites are represented by lymphocytes scattered diffusely throughout the lamina propria (LP) and within the epithelium. In this study, the RLN and LP were examined separately, because the cellular compositions of the two compartments are distinct and thus the effects of SIV infection may differ. For example, in the rectal mucosa of HIV-infected humans, depletion of CD4+ lymphocytes is more severe in the LP than in the RLN. 21 HIV/SIV infection could nevertheless interfere with the induction of immune responses in the RLN by affecting the processing and presentation of incoming foreign antigens and pathogens, depleting T cell help for generation of antigen-specific B cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), and impairing cytokine production for isotype switch to IgA. In the LP, infection could disrupt other mucosal protective functions. Indeed, others have observed altered morphology of subepithelial macrophages in SIV-infected monkey colon 5,6 and a reduction in LP IgA-producing cells in both HIV-infected humans and SIV-infected macaques. 21-23

To examine in more detail the effects of SIV infection on both inductive and effector sites in the rectal mucosa, cells with antigen-presentation capacity in both RLN and LP were identified by visualizing MHC-II and the co-stimulatory molecules CD40 and B7-2 (CD86). Possible alterations in mucosal homing/trafficking of cells to both compartments were evaluated by immunocytochemical identification of cells expressing the mucosal homing receptor α4β7 and the peripheral lymph node homing receptor L-selectin. In addition, possible alterations in B cell populations were analyzed with regard to expression of molecules associated with antigen presentation (MHC-II and CD40), differentiation state (CD20), and expression of immunoglobulin isotypes.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Rectal and distal colonic tissues (defined here as 3 to 10 cm and 10 to 15 cm from the anal verge, respectively) were obtained at necropsy from five naive, SIV-uninfected macaques, three short-term (2 months) SIV-infected macaques, and eight long-term (5 to 21 months) SIV-infected macaques. Although most of the sections from each group were from the rectum some were from the adjacent distal colon, a region in which the mucosa is histologically identical to the rectum; thus, for brevity all of the sections used in this study are referred to as rectal tissue. The three short-term SIV-infected macaques were inoculated intravenously with SIVmac239 50 days before sacrifice. The eight long-term SIV-infected rhesus macaques were inoculated intravenously (or in one case, vaginally) with SIVmac251 or SIVmac239 5 to 21 months before sacrifice. Table 1 ▶ shows designated animal numbers, numbers of CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood, and percentages of mucosal CD4+ T cells measured by flow cytometric analysis of mucosal T cell populations obtained from other intestinal regions as part of a previous study. 11 All of the SIV-infected animals in this study, with the exception of animal no. A97-254, had opportunistic infections of the GI tract as judged by microbial culture, histopathology, and/or clinical symptoms.

Table 1.

Summary of Rhesus Macaques Used in this Study

| Animal no. | Sex | SIV strain | (Inoc. rte) | Time infected | CD4+ cells | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gut LP (FACS %) | Blood (no./ml) | |||||

| Naive | ||||||

| A97-60 | F | 19 C | NP | |||

| A97-128 | M | 28 C | 952 | |||

| A95-405 | M | 44 C | 1108 | |||

| A95-385 | M | 38 C | 1756 | |||

| A95-397 | M | 29 C | 1536 | |||

| Short-term SIV-infected (2 months) | ||||||

| A94-576 | M | 239* | (iv) | 50 d | 5 C | 971 |

| A96-529 | M | 239 | (iv) | 50 d | 7 C | 733 |

| A96-91 | M | 239 | (iv) | 50 d | 4 J | 2157 |

| Long-term SIV-infected (5 to 21 months) | ||||||

| A97-252 | F | 251† | (iv) | 5 mo | 5 I | 1268 |

| A97-76 | M | 251 | (iv) | 5 mo | 2 I | 50 |

| A97-253 | F | 251 | (iv) | 6 mo | 5 J | 1911 |

| A97-254 | F | 251 | (iv) | 6 mo | 2 C | 521 |

| A97-46 | F | 251 | (ivag) | 6 mo | NP | 371 |

| A95-458 | M | 239 | (iv) | 8 mo | NP | NP |

| A95-232 | M | 239 | (iv) | 15 mo | NP | 429 |

| A97-446 | M | 239 | (iv) | 21 mo | NP | 337 |

Abbreviations: C, colon; J, jejunum; I, ileum; NP, assay not performed.

*SIVmac 239.

†SIVmac 251.

Immunofluorescent Staining and Analysis

The reagents used in this study and their sources are shown in Table 2 ▶ . Immediately after sacrifice, rectal and colonic tissues were dissected, embedded in optimum cold temperature medium (OCT; Miles Inc., Elkhart, IN), frozen in 2-methylbutane (J. T. Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ), chilled by dry ice, and kept at −80°C until sectioned. Other tissue samples were fixed in 4% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin using standard procedures. Staining with all antibodies (with the exception of anti-S100 and HAM-56) was performed using 5-μm cryostat sections mounted on Superfrost Plus glass slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), dried at room temperature for 4 hours to overnight, and kept at −80°C until use. Before immunofluorescent staining the slides were brought to room temperature and immediately fixed with 100% acetone for 10 minutes at room temperature. The anti-S-100 antibody was applied to fixed, paraffin-embedded sections. The sections were washed three times, 5 minutes each in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and blocked in PBS containing 10% normal serum of the species in which the secondary reagent was raised. Primary reagents were applied to sections and incubated for 45 minutes at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. The sections were washed three times, 5 minutes each in PBS containing 0.05% Tween (PBS/Tween), and secondary reagents were applied for 45 minutes at room temperature. The sections were again washed three times, 5 minutes each in PBS/Tween and 5 minutes in PBS. Coverslips were mounted with Gel/Mount (Biomeda Corp, Foster City, CA) and slides were kept in the dark at room temperature until studied and photographed. Staining was repeated on at least two slides for each animal, with sections at least 30 μm apart. The intensity of fluorescent staining was generally similar on all sections analyzed, and background fluorescence was low.

Table 2.

List of Primary and Secondary Reagents Used

| Specificity | Source | Supplier* |

|---|---|---|

| Primary antibodies | ||

| Rhesus IgA | Goat | Accurate Scientific |

| Rhesus IgG | Goat | Accurate Scientific |

| Human IgM | Goat | SBA |

| Human CD20 | Mouse MAb | DAKO |

| Human CD40 | Mouse MAb | Ancel |

| Human CD86 (B7-2) | Mouse MAb | Pharmingen |

| Human CD3 | Rabbit | DAKO |

| Human CD4 | Mouse MAb | Ortho Diagnostics |

| Human CD8 | Mouse MAb | Beckton & Dickinson |

| Human CD1a | Mouse MAb | Beckton & Dickinson |

| Bovine S100 | Rabbit | DAKO |

| Human HLA-DR | Mouse MAb | Beckton & Dickinson |

| Human CD68 | Mouse MAb | DAKO |

| HAM56 | Mouse MAb | DAKO |

| Human Ki67 | Mouse MAb | Zymed |

| L-selectin (CD62L) | Mouse MAb | Pharmingen |

| Integrin α4β7 | Mouse MAb (ACT-1) | Leukosite |

| Secondary reagents | Conjugated to | |

| Rabbit anti-goat IgG | Biotin or FITC | Sigma |

| Swine anti-rabbit IgG | TRITC | DAKO |

| Rat anti-mouse IgG1 | FITC or phycoerythrin | SBA |

| Rat anti-mouse IgG2a | FITC or phycoerythrin | SBA |

| Sheep anti-mouse IgG | Phycoerythrin | SBA |

| Goat anti-mouse IgG | TRITC | Kirkegaard & Perry |

| Streptavidin | FITC or phycoerythrin | Sigma |

*SBA, Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL; Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corp., Westbury, NY; DAKO Corp., Carpinteria, CA; Ancel Immunology Research Products, Bayport, MN; Pharmingen, San Diego, CA; NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, NIAID, Rockville, MD; Becton and Dickinson, San Jose, CA; Zymed Laboratories, Inc., San Francisco, CA; Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO; Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD.

Positively stained RLN and LP cells were counted in 2 to 3 representative medium power fields per slide (25× objective and 10× eyepiece). Areas adjacent to RLN were not included in LP cell counts. Because in most fields there were some cells of borderline staining intensity and because counting cells in the RLN was difficult because of the close packing of lymphocytes, the counts could not be considered strictly quantitative. However, scores within a decile could be assigned with some confidence, and for each slide the average score was noted. Qualitative average scores for each animal (+ to ++++) were assigned as indicated in the Table ▶ footnotes.

Flow Cytometry

The absolute numbers of CD4+ cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and percentage of intestinal CD4+ T cells was determined by flow cytometry on single-cell suspensions prepared from intestinal tissues as previously described. 24 Briefly, pieces of jejunum, ileum, and/or colon were removed, washed in PBS, and cut into small pieces. The intestinal pieces were treated sequentially with magnesium and calcium-free Hanks’ balanced salt solution containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid to remove epithelial and intraepithelial cells, and then with RPMI containing 5% fetal calf serum, L-glutamine, streptomycin, and collagenase (type II; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) to release LP cells. The cells were separated on a Percoll density gradient, washed, and counted. Cell suspensions were then stained with an excess of phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-human CD4 monoclonal antibody (OKT4; Ortho, Raritan. NJ) for 30 minutes at 4°C, washed in PBS, and fixed overnight in 2% paraformaldehyde. Cells were analyzed using a FACS Scan flow cytometer and Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). Percentages of intestinal CD4 cells were determined by gating through lymphocytes using a bivariate dot plot display of forward versus side scatter as previously described. 24

Localization of SIV-Infected Cells by in Situ Hybridization and Immunohistochemistry

To identify cells that harbored viral mRNA, nonradioactive in situ hybridization was combined with immunohistochemistry on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections from rectum and distal colon as previously described. 11 Briefly, a DNA probe corresponding to the entire SIVmac239 genome was labeled with digoxigenin-11-dUTP by random priming (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) and hybridized onto paraffin-embedded sections overnight. Labeled cells were visualized using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-digoxigenin antibodies and diaminobenzidine plus nickel cobalt to give a black precipitate. In double-label experiments to determine whether cells of monocyte/macrophage lineage were infected, this was followed by immunostaining with HAM-56 using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and development using diaminobenzidine alone, resulting in an orange/brown precipitate. Other paraffin sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) were used for histological analysis of rectal mucosal tissue.

Results

Organized Lymphoid Tissues in the Rectal Mucosa of Rhesus Macaques

RLNs were present at the recto-anal junction and at frequent intervals in the rectal and distal colonic tissues examined. The majority of RLN were located in the submucosa, but because serial sections were not examined it is possible that some of these extended into the mucosa as previously described in humans. 25 The association of mucosal nodules with follicle-associated epithelium containing M cells was seen in only a few of the sections examined. The histological organization of the RLN in macaques was similar to that reported for organized mucosal lymphoid tissues in the human colon. 26

Changes in the Distribution of CD4+ T Cells in Rectal Mucosa of SIV-Infected Macaques

Flow cytometry of single-cell suspensions prepared from small and large intestines of intravenously SIV-inoculated rhesus macaques showed that numbers of CD4+ cells were dramatically reduced in the intestinal mucosa at early times after infection, 2,10-13 but this decrease was less dramatic in the Peyer’s patches which contain both organized and diffuse lymphoid tissues. 11 FACS analysis of mucosal tissues from the monkeys in this study confirmed previous reports, showing a dramatic decrease in mucosal CD4+ cells (Table 1) ▶ . To separately evaluate the organized and diffuse lymphoid tissue of the rectum, we directly visualized CD4+ cells in RLN and LP of SIV-inoculated and naive macaques by immunofluorescent staining. As expected from earlier reports of the small intestine and colon, numbers of CD4+ cells were much reduced in the rectal LP of SIV-infected macaques (data not shown). However, many CD4+ cells were present in the RLN of SIV-infected macaques even in monkeys at late stages of SIV infection and AIDS. The fact that organized lymphoid tissues of the rectal mucosa of these SIV-infected macaques contained CD4+ target cells, confirms previous observations in the small intestinal mucosa of SIV-infected macaques 11 and the rectal mucosa of HIV-infected humans. 21

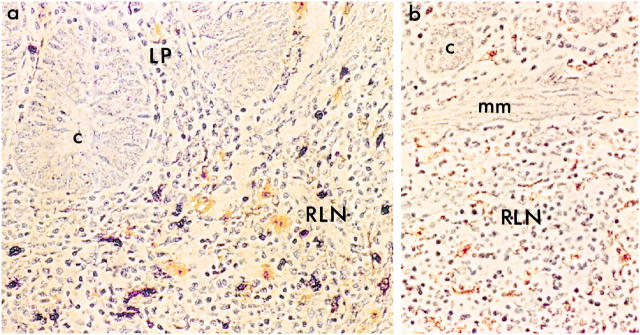

In situ hybridization showed that in all specimens examined ranging from 2 months postinfection to those with terminal AIDS, the majority of SIV-containing cells were in the RLN and fewer were in the LP. This is consistent with earlier findings in small and large intestines of macaques infected for 3 to 17 months, 5 and in the upper GI tract at 2 months postinfection. 11 In situ hybridization combined with immunohistochemical staining with HAM-56, a marker for macrophage lineage cells, showed that some (but not all) of the SIV-infected cells in both RLN and LP were macrophages (Figure 1) ▶ . Whether the numbers of SIV-infected mucosal macrophages was enhanced by opportunistic GI infections in these animals, as previously observed in esophageal mucosa, 27 could not be determined because 10 of the 11 infected animals harbored such infections. In any case, these results confirmed that rectal mucosal T cells and macrophages, both of which express HIV/SIV co-receptors 28 may serve as a reservoir of SIV in the rectum even after LP CD4+ T cells are depleted.

Figure 1.

Identification of SIV-infected cells in RLN and LP. Macrophages were identified by immunohistochemistry using the HAM-56 antibody followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (orange/brown). SIV-infected cells were detected by in situ hybridization using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibodies and developed with diaminobenzidine and nickel-cobalt (dark purple/black). Infected cells were present primarily in RLN of SIV-infected macaques (a: animal no. A94-576) but not in uninfected controls (b: animal no. A95-397) (mm, muscularis mucosae; c, crypt). Original magnification, ×405.

Loss of Cells Expressing the Mucosal Homing Receptor α4β7 in SIV-Infected Macaques

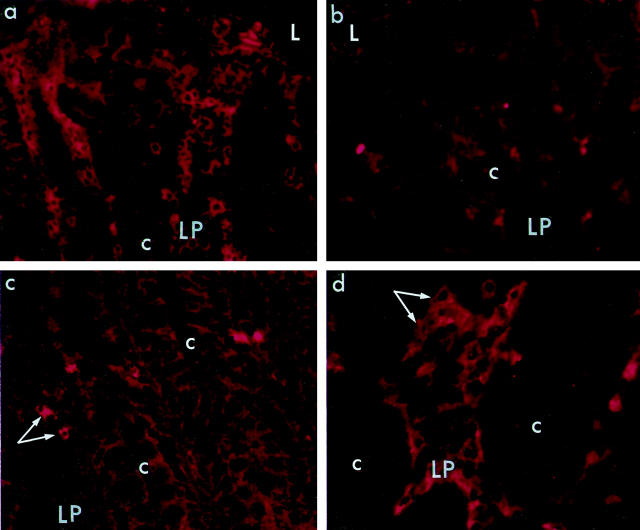

Lymphocytes migrate selectively into intestinal mucosal lymphoid tissues on the basis of the surface expression of α4β7 which interacts with the mucosal addressin MAdCAM-1 expressed primarily on mucosal endothelial cells. Although the homing receptor L-selectin (CD62L) may also be expressed by some mucosal lymphocytes, it is generally considered a homing receptor for systemic lymphoid tissues. 29 Because cell trafficking and the presence of mucosa-specific lymphocytes may be important in the pathogenesis of HIV/SIV and in the ability of infected animals to mount mucosal immune responses, we studied the distribution of α4β7+ and L-selectin+ cells in the RLN and LP of SIV-infected and naive macaques. In naive macaques α4β7+ cells were present in high numbers in RLN and were also numerous in the LP (Figure 2a ▶ , Table 3 ▶ ). In contrast, the majority of long-term SIV-infected macaques had few α4β7+ cells in either RLN or LP (Figure 2b ▶ and Table 3 ▶ ). In RLN of most of the naive and infected macaques there were few or no L-selectin+ cells, as expected. Although four out of 11 SIV-infected macaques had relatively high numbers of L-selectin+ cells in RLN, there were wide variations among individuals and no consistent pattern emerged (Table 3) ▶ . In the LP of naive macaques, low numbers of L-selectin+ cells were consistently present (Figure 3c) ▶ . However, in the LP of the three macaques infected for 2 months the numbers of L-selectin+ cells in LP were high, and L-selectin+ cells were also elevated in five of the eight animals infected for longer times (Figure 3d ▶ and Table 3 ▶ ). These findings suggest that in SIV-infected macaques, mucosal trafficking of lymphocytes may be altered or mucosally directed α4β7+ cells may fail to survive in the rectal mucosa.

Figure 2.

Decreased numbers of α4β7+ cells and increased L-selectin+ cells in LP of rectal mucosa of SIV-infected macaques. a and b: α4β7+ cells were numerous in LP of a naive macaque (a: animal no. A95-405), but depleted in LP of an SIV-infected animal (b: animal no. A97-252). Sections were stained with mouse anti-human α4β7 antibody followed by PE-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (L, lumen of rectum; c, crypt). Original magnification, ×405. c and d: L-selectin+ cells (arrows) were sparse in LP of a naive macaque (c: animal no. A97-128) but were numerous in LP of an SIV-infected macaque (d: animal no. A97-252, shown at higher magnification). Sections were stained with mouse anti-human CD62L (L-selectin), followed by PE-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (c, crypt). Original magnifications ×405 (c); and ×460 (d).

Table 3.

Cells Expressing Homing Receptors in Rectal Mucosa

| Animal no. | Lymphoid nodules | Lamina propria | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-selectin | α4β7 | L-selectin | α4β7 | |

| Naive | ||||

| A97-60 | nf | ++++ | − | +++ |

| A97-128 | + | +++ | + | +++ |

| A97-405 | − | ++++ | + | +++ |

| A97-385 | nf | ++++ | + | ++++ |

| A97-397 | ++ | nf | + | +++ |

| Short-term SIV-infected (2 months) | ||||

| A94-576 | nf | nf | +++ | ++ |

| A96-529 | ++ | − | +++ | ++ |

| A96-91 | nf | nf | +++ | ++ |

| Long-term SIV-infected (5 to 21 months) | ||||

| A97-252 | + | − | ++ | − |

| A97-76 | ++ | − | ++ | − |

| A97-253 | − | − | ++ | + |

| A97-254 | nf | nf | + | + |

| A97-461 | + | + | + | + |

| A97-458 | +++ | − | ++ | +++ |

| A97-232 | ++ | − | ++ | + |

| A97-446 | − | ++ | + | + |

Approximate number of positively stained cells per 25× field: 0 to 10 (−); 10 to 20 (+); 20 to 30 (++); 30 to 50 (+++); 50 and over (++++). nf; no lymphoid nodules found on sections.

Figure 3.

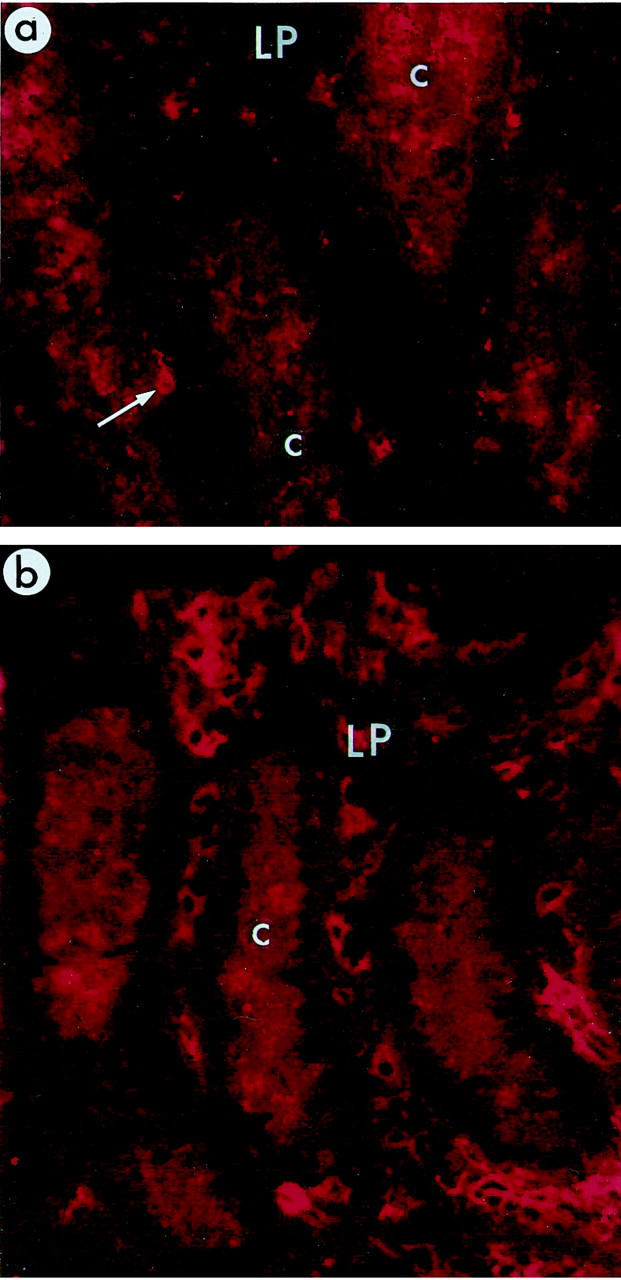

Distribution of B7-2+ cells in rectal mucosa. Relatively few B7-2+ cells (arrow) were present in rectal LP of naive macaques (a: animal no. A97--60), but B7-2+ cells were abundant in LP of SIV-infected macaques (b: animal no. A94-576). The antibodies used here (mouse anti-human B7-2 followed by PE-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG) produced some background staining in the cytoplasm of crypt epithelial cells (c, crypt; L, lumen of rectum). Original magnification, ×405.

Cells with Antigen Presentation Capacity Are Not Reduced in Rectal Mucosa of SIV-Infected Macaques

In the normal intestinal mucosa, cells capable of presenting antigens via the MHC Class II pathway are particularly abundant in organized inductive sites but are also present in the LP. To confirm their distribution in the normal macaque rectum and to evaluate possible changes in SIV-infected animals, we began by visualizing the MHC II molecule HLA-DR, the macrophage lineage marker CD68, and the putative dendritic cell markers CD1a (a marker of Langerhans cells in stratified epithelia) and S100, an actin-associated protein enriched in dendritic cells. In RLN of naive macaques, we found CD68+HLA-DR+ macrophages scattered throughout the nodules and in the LP, CD68+HLA-DR+ cells were abundant, particularly below the surface epithelium (data not shown). Similar cell distributions were observed in sections stained with a mouse anti-human CD11b reagent. No CD1a+ cells were found in naive macaque rectal mucosa in agreement with a previous report, 30 although using the same reagent we could readily detect CD1a + dendritic cells in frozen sections of tonsil (data not shown). Relatively few S100+ cells were observed in LP or RLN of naive macaques and in RLN, most of the S100+ cells were located at the periphery of the lymphoid nodules. We could not detect any alterations in the numbers or distribution of cells expressing any of these markers in SIV-infected rectal mucosa. These findings confirm the distribution of macrophage lineage cells observed by others in SIV-infected and uninfected macaque colonic mucosa. 5

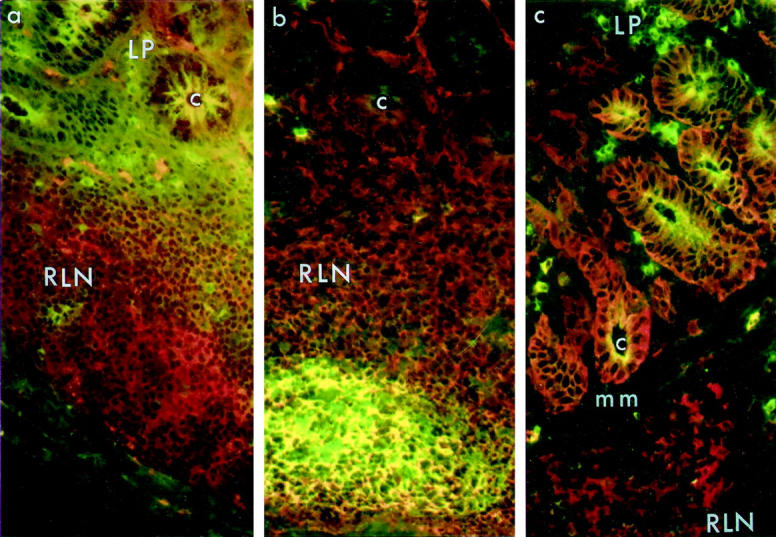

We then documented the distribution of cells expressing the co-stimulatory molecules B7-2 (CD86), and CD40. In naive macaques, the RLN contained high numbers of B7-2+ cells scattered throughout the nodules except in areas that appeared to be germinal centers. This distribution resembled that of CD68+ macrophages. There were also many CD40+ cells scattered throughout the RLN and a few of these, located at the periphery of the nodules, were intensely stained and had a dendritic morphology. In SIV-infected macaques, we detected no alterations in numbers and localization of B7-2+ or CD40+ cells in RLN (Figure 4a ▶ and Table 4 ▶ ). These finding confirm that the lymphoid nodules of the rectal mucosa are potential sites of antigen-presentation activity and that this immunophenotype is maintained in RLN, even in long-term SIV-infected macaques. In the LP, the putative effector site, we detected few or no B7-2+ cells in four of the five naive macaques (Figure 3a ▶ and Table 4 ▶ ). In contrast, many B7-2+ cells were present in the LP of all three short-term SIV-infected macaques and four of eight long-term SIV-infected macaques (Figure 3b ▶ and Table 4 ▶ ). We did not detect CD40+ cells in the LP of any naive macaques and detected CD40+ cells in the LP of only three of 11 SIV-infected macaques (Table 4) ▶ . These data suggest that the LP of SIV-infected macaques contains cells with the potential to function as antigen-presenting cells, despite the marked depletion of CD4+ T helper cells.

Figure 4.

Distribution of IgM+, CD40+, and MHCII+ cells in rectal mucosa. a: IgM and CD40. An abundance of CD40+ cells (red) in RLN but not in LP was detected in both naive and SIV-infected rectal tissue (shown here). The cluster of IgM+ cells that was seen in the centers of most follicles was not present in this section. Frozen sections were double-stained with biotinylated goat anti-human IgM and mouse anti-human CD40, followed by streptavidin-FITC (green) and PE-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1 (red). b and c: IgM and MHCII. Double immunofluorescence staining of naive (b: animal no. A97-60) and SIV-infected (c: animal no. A97-252) mucosa to detect IgM (green) and MHCII (red). Many B cells in the central regions of RLN expressed both IgM and MHCII (yellow) in both naive (b) and SIV-infected mucosa (in c, the central region of the follicle is not seen). IgM+ cells in LP of both naive (b) and SIV-infected (c) rectal mucosa were MHCII-negative. Expression of MHCII on crypt epithelial cells was variable, but was present in most specimens from both naive and infected animals (mm, muscularis mucosae; c, crypt). Original magnification, ×405.

Table 4.

Cells Expressing Co-stimulatory Markers in Rectal Mucosa

| Animal no. | Lymphoid nodules | Lamina propria | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B7-2 | CD40 + IgM− | B7-2 | CD40 + IgM− | |

| Naive | ||||

| A97-60 | nf | ++ | NP | NP |

| A97-128 | ++ | +++ | NP | − |

| A97-405 | nf | +++ | + | − |

| A97-385 | +++ | NP | +++ | + |

| A97-397 | nf | +++ | + | + |

| Short-term SIV-infected (2 months) | ||||

| A94-576 | nf | nf | +++ | +++ |

| A96-529 | +++ | +++ | +++ | − |

| A96-91 | nf | nf | +++ | − |

| Long-term SIV-infected (5 to 21 months) | ||||

| A97-252 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| A97-76 | ++ | ++++ | ++ | − |

| A97-253 | nf | +++ | + | − |

| A97-254 | +++ | nf | + | − |

| A97-461 | ++ | ++++ | + | − |

| A97-458 | +++ | ++++ | +++ | ++ |

| A97-232 | ++++ | ++++ | ++ | + |

| A97-446 | +++ | ++++ | + | − |

Approximate number of positively stained cells per 25× field: 0 to 10 (−); 10 to 20 (+); 20 to 30 (++); 30 to 50 (+++); 50 and over (++++). nf, no lymphoid nodules found on sections; NP, staining not performed.

To determine whether B cells in the rectal mucosa expressed MHC II and co-stimulatory molecules, we performed double-immunofluorescent staining of IgM with HLA-DR and with CD40. High and comparable numbers of cells expressing IgM and HLA-DR, and cells expressing IgM and CD40, were present in RLN of both naive and SIV-infected macaques (Figure 4 ▶ and Table 5 ▶ ). The IgM + MHCII+ cells were generally located outside apparent germinal center areas, whereas the IgM + CD40+ cells were found within these areas. These data suggest that some RLN B cells are potentially capable of functioning as antigen presenting cells (APC). Although IgM+ cells were present in the LP of naive macaques and were abundant in LP of SIV-infected macaques, none of them expressed MHCII+ or CD40+ (data not shown).

Table 5.

B Cell Phenotypes in Rectal Lymphoid Nodules

| Animal no. | IgA+ | IgM + CD20+ | IgM + Ki67+ | IgM + MHCII+ | IgM + CD40+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naive | |||||

| A97-60 | − | +++ | nf | +++ | NP |

| A97-128 | − | +++ | NP | +++ | ++++ |

| A97-405 | ++ | NP | nf | +++ | ++ |

| A97-385 | nf | NP | +++ | +++ | NP |

| A97-397 | − | NP | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| Short-term SIV-infected (2 months) | |||||

| A94-576 | nf | NP | nf | +++ | ++ |

| A96-529 | − | NP | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| A96-91 | nf | NP | nf | +++ | nf |

| Long-term SIV-infected (5 to 21 months) | |||||

| A97-252 | − | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| A97-76 | − | NP | − | +++ | ++ |

| A97-253 | − | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| A97-254 | nf | +++ | − | +++ | nf |

| A97-461 | − | NP | nf | +++ | ++++ |

| A97-458 | nf | NP | NP | +++ | ++++ |

| A97-232 | nf | NP | nf | +++ | ++++ |

| A97-446 | − | NP | ++ | +++ | ++++ |

Approximate number of positively stained cells per 25× field: 0 to 10 (−); 10 to 20 (+); 20 to 30 (++); 30 to 50 (+++); 50 and over (++++). nf, no lymphoid nodules found on sections; NP, staining not performed.

Immunoglobulin Isotypes and Differentiation of B Cells in Rectal Mucosa of Naive and SIV-Infected Macaques

Decreases in IgA+ cells and increases in IgM+ cells were previously reported in the LP of small intestine and colon of SIV-infected macaques, 23 but the phenotypes of B cells in the rectal mucosa had not been examined. Rectal B cells expressing immunoglobulin isotypes were visualized by double immunofluorescent staining of IgM with IgA or IgG. The RLN of both naive and SIV-infected macaques contained mainly IgM+ cells and few or no IgA+ (Table 5) ▶ or IgG+ (data not shown) cells, as others have observed (J. Mestecky, personal communication). The LP of SIV-infected macaques showed an increase in the numbers of IgM+ cells and a decrease in IgA+ cells when compared to the LP of naive macaques (data not shown), consistent with previous reports. 23 By double-immunofluorescent staining to visualize IgM and secretory component (SC), we detected similar levels of SC on crypt epithelial cells and co-localization of SC and IgM within epithelial cells and in the lumen of both naive and SIV-infected macaques, as expected (data not shown).

The increase in IgM+ B cells in SIV-infected LP raised the possibility that some of these cells might not only have failed to switch to the IgA isotype, but also failed to terminally differentiate into plasma cells. To determine what proportion of the IgM+ B cells in rectal LP were terminally differentiated, we performed double-immunofluorescent staining of IgM with CD20 (a B-cell differentiation marker expressed on B cells but not plasma cells) and Ki67 (a cell proliferation marker). In RLN of both naive and SIV-infected macaques, we found high numbers of IgM + CD20+ cells throughout the nodules as expected, indicating that the majority of B cells in these inductive sites were not plasma cells (Table 5) ▶ . In RLN, there were relatively few proliferating IgM + Ki67+ cells in both naive and SIV-infected macaques and these were confined mostly to the germinal centers as expected. In the LP of both SIV-infected and naive macaques, none of the IgM+ cells co-expressed either CD20 or Ki67 (datanot shown), confirming that all of these cells were terminally differentiated plasma cells.

Discussion

Lymphoid tissues in the intestinal mucosa show two distinct arrangements reflecting their differing roles in mucosal immune responses. The organized mucosal lymphoid nodules (also termed lymphoid follicles) are local inductive sites where antigens are sampled and lymphocytes are activated and expanded. In contrast, most of the LP of the intestinal mucosa is a widespread, diffuse lymphoid tissue where antigen-specific, terminally differentiated lymphocytes perform effector functions. This study of the rectal mucosa of intravenously inoculated macaques has shown that the effects of SIV infection on the mucosal immune system are more complex than previously appreciated. Immunopathology was most evident in the diffuse lymphoid tissue of the LP. CD4+ T cells and IgA-producing B cells were dramatically depleted from LP as previously observed in more proximal intestinal regions but in addition, cells expressing the B7-2 co-stimulatory molecule were increased and cells expressing the α4β7 mucosal homing receptor were depleted. In contrast, the cellular composition of organized mucosal lymphoid nodules showed fewer alterations; in particular, CD4+ T cells and activated antigen-presenting cells persisted in these inductive sites despite the presence of many SIV-infected cells.

There is abundant evidence that organized mucosal lymphoid tissues play a major role in antigen sampling and generation of lymphocytes including specific IgA effector B cells and T cells. This involves active lymphocyte proliferation, local production of certain cytokines, and continuous cellular trafficking. 19,20,31,32 Most of the available information about the cellular composition and function of mucosal lymphoid nodules has been obtained using macroscopically visible Peyer’s patches of the small intestine, where lymphoid follicles are aggregated. The structure and function of solitary lymphoid nodules that are numerous in the lower colon and rectum 26 is generally assumed to be similar to those of Peyer’s patches, although detailed studies have not been done. In normal intestine, antigens and pathogens are delivered by M cells in the follicle-associated epithelium from the lumen to subepithelial antigen-presenting cells, and hence into organized lymphoid follicles. 33,34 The organized lymphoid nodules of Peyer’s patches generally have a central B cell-rich region (which may include a germinal center) containing a network of macrophages and dendritic cells where antigen presentation, B cell expansion, and isotype switch is thought to occur. 20,31,32 Adjacent to the B cell center are CD4+ T cell-rich areas where monocytes and naive and memory lymphocytes enter the mucosa via high endothelial venules, directed by their α4β7 mucosal homing receptors. Our findings indicate that the lymphoid nodules of normal macaque rectum, like those of Peyer’s patches, are sites of antigen presentation as evidenced by expression of MHC-II and possibly B7-2 by macrophages and MHC-II and CD40 by IgM+ B cells. Moreover, B cell proliferation occurs in rectal nodules, as indicated by the presence of IgM + /Ki67+ and IgM + CD20+ cells. We confirmed that B cells in RLN of both naive and SIV-infected macaques were dominated by IgM+ cells, in contrast to the IgA+ cells observed in Peyer’s patches of other mammalian species including humans. 20,31,32

At the postinfection times studied here (2 months or more), most of the SIV-infected cells in the rectal mucosa appeared to be located in the lymphoid nodules, as others have observed. 5,6,11 Nevertheless, we found immunophenotypic evidence of high antigen presentation capacity in these inductive sites. The numbers of CD68 + MHCII+, IgM + MHCII+, CD40+, and B7-2+ cells in RLNs of naive and SIV-infected rhesus macaques were comparable, and the presence of CD4+ cells in mucosal nodules of SIV-infected macaques indicated that some T cell help was maintained in these inductive sites. The only clear change detected in the nodules was a decrease in the numbers of cells expressing the mucosal homing receptor α4β7.

A similar shift was observed in the LP of SIV-infected animals, where α4β7+ cells were depleted and L-selectin+ cells were generally more numerous than in naive controls. This observation is difficult to interpret because almost all of the SIV-infected macaques in our study had signs of gastrointestinal inflammation and/or documented opportunistic mucosal infections. Because inflammatory and infectious diseases of the GI tract are generally accompanied by an influx of α4β7+ cells into the LP, 35,36 we expected an increase in the number of α4β7+ cells in the LP of SIV-infected macaques. The fact that we observed a decrease suggests that the loss of α4β7+ cells in the rectal mucosa of SIV-infected macaques may be specifically associated with SIV infection. CD4+ T cells are depleted early in the intestinal LP, 10-13 and it may be argued that the reduction in the number of α4β7+ cells simply reflects the loss of CD4+ T cells. On the other hand CD8+ T cells, whose numbers are increased after SIV/HIV infection 11 as well as B cells, plasma cells, and macrophages, can also express α4β7 29,36-38 and similar numbers of total CD3+ T cells were observed in the intestinal mucosa of SIV-infected and naive macaques in previous studies. 11 It remains to be determined whether the SIV-associated loss of mucosal α4β7+ cells reflects altered mucosal trafficking as suggested by others 15 or selective loss of mucosally directed cells.

In naive macaques, the expression of the co-stimulatory molecules CD40 and B7-2 was primarily confined to the RLN and not the LP, consistent with the hypothesis that the organized lymphoid tissues are the principal inductive sites of the rectum. In SIV-infected macaques, however, numbers of B7-2+ macrophages were increased in the LP. Although this observation suggests that antigen-presentation activity was elevated in SIV-infected rectal mucosa, it cannot be directly attributed to SIV. Antigenic stimulation from the opportunistic mucosal infections in these animals could have affected the numbers and activity of these cells, as observed by others in esophageal mucosa of SIV-infected macaques. 27

In conclusion, our observations show that the organized lymphoid tissues of the rectal mucosa of SIV-infected macaques retain the immunophenotypic characteristics associated with high antigen-presentation capacity. In the LP, however, the loss of α4β7+ cells, along with loss of CD4+ T cells and changes in the isotype distribution of secreted antibodies, suggest alterations in immune effector functions. Elucidation of the significance of these changes will require further studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Ronald Desrosiers for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Marian R. Neutra, Ph.D., GI Cell Biology Laboratory, Enders 1220, Children’s Hospital, 300 Longwood Ave., Boston, MA 02115. E-mail: neutra_m@al.tch.harvard.edu.

Supported by National Institutes of Health Integrated Preclinical/Clinical AIDS Vaccine Development Grant A13565; National Institutes of Health Research Grants AI34757, AI38559, AI25328, and DK50550; and National Institutes of Health Grant DK34854 to the Harvard Digestive Diseases Center.

References

- 1.Smith PD, Wahl SM: Immunobiology of mucosal HIV infection. The Human Mucosal B-Cell System. Mucosal Immunology, ed 2. Edited by PL Ogra, J Mestecky, ME Lamm, W Strober, W Bienenstock, J McGhee. New York, Academic Press, 1999, pp 977–992

- 2.Veazey RS, Lackner AA: The gastrointestinal tract and the pathogenesis of AIDS. AIDS 1998, 12(suppl A):S35-S42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathijs JM, Hing M, Grierson J, Goldschmidt C, Cooper DA, Cunningham AL: HIV infection of rectal mucosa. Lancet 1988, 1:8594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kotler DP, Reka S, Borcish A, Cronin WJ: Detection, localization, and quantitation of HIV-associated antigens in intestinal biopsies from patients with HIV. Am J Pathol 1991, 139:823-830 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heise C, Vogel P, Miller CJ, Halsted CH, Dandekar S: Simian immunodeficiency virus infection of the gastrointestinal tract of rhesus macaques: functional, pathological, and morphological changes. Am J Pathol 1993, 142:1759-1771 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heise C, Miller CJ, Lackner A, Dandekar S: Primary acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection of intestinal lymphoid tissue is associated with gastrointestinal dysfunction. J Infect Dis 1994, 169:1116-1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuller L, Beneviste RE, Tsai CC, Clark EA, Palacino P, Watanabe R, Overbaugh J, Katze MG, Morton WR: Intrarectal inoculation of macaques by the simian immunodeficiency virus, SIVmneE11S: CD4+ depletion and AIDS. J Med Primatol 1994, 23:397-409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McClure HM, Andersen DC, Fultz DN, Ansari AA, Lockwood E, Brodie A: Spectrum of disease in macaque monkeys chronically infected with SIV/SMM. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 1989, 21:13-24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehrenpreis ED: Small intestinal manifestations of HIV infection. Int J STD AIDS 1995, 6:149-155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider T, Jahn H-U, Schmidt W, Reicken E-O, Zeitz M, Ullrich R: Loss of CD4+ lymphocytes in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is more pronounced in the duodenal mucosa than in peripheral blood. Gut 1995, 37:524-529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veazey RS, DeMaria M, Chalifoux LV, Shvetz DE, Pauley DR, Knight HK, Rosenweig M, Johnson RP, Desrosiers RC, Lackner A: Gastrointestinal tract as a major site of CD4+ T cell depletion and viral replication in SIV infection. Science 1998, 280:427-431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smit-McBride Z, Mattapallil JJ, McChesney M, Ferrick D, Dandekar S: Gastrointestinal T lymphocytes retain high potential for cytokine responses but have severe CD4+ T-cell depletion at all stages of simian immunodeficiency virus infection compared to peripheral lymphocytes. J Virol 1998, 72:6646-6656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kewenig S, Schneider T, Hohloch K, Lampe-Dreyer K, Ullrich R, Stolte N, Stahl-Hennig C, Kaup FJ, Stallmach A, Zeitz M: Rapid mucosal CD4+ T-cell depletion and enteropathy in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaques. Gastroenterology 1999, 116:1115-1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiviat NB, Critchlow CW, Hawes SE, Kuypers J, Surawicz C, Gollbaum G, Van Burik JA, Lampinen T, Holmes KK: Determinants of human immunodeficiency virus DNA and RNA shedding in the anal-rectal canal of homosexual men. J Infect Dis 1998, 177:571-578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pauza CD, Emau P, Salvato MS, Trivedi P, MacKenzie D, Malkovsky M, Uno H, Schultz KT: Pathogenesis of SIVmac251 after atraumatic inoculation of the rectal mucosa in rhesus monkeys. J Med Primatol 1993, 22:154-161 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clerici M, Clark EA, Polacino P, Axberg I, Kuller L, Casey NI, Morton WR, Shearer GM, Benveniste RE: T-cell proliferation to subinfectious SIV correlates with lack of infection after challenge of macaques. AIDS 1994, 8:1391-1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forrest BD, Shearman DJC, LaBrooy JT: Specific immune response in humans following rectal delivery of live typhoid vaccine. Vaccine 1990, 8:209-212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kozlowski PA, Cu-Uvin S, Neutra MR, Flanigan TP: Comparison of the oral, rectal, and vaginal immunization routes for induction of antibodies in rectal and genital tract secretions of women. Infect Immun 1997, 65:1387-1394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGhee JR, Lamm ME, Strober W: Mucosal immune responses: an overview. ed 2 Ogra PL Mestecky J Lamm ME Strober W Bienenstock J McGhee J eds. Handbook of Mucosal Immunology, 1999, :pp 485-506 Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandtzaeg P, Farstad IN: The human mucosal B-cell system. ed 2 Ogra PL Mestecky J Lamm ME Strober W Bienenstock W McGhee J eds. Mucosal Immunology, 1999, :pp 439-468 Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clayton F, Snow G, Reka S, Kotler DP: Selective depletion of rectal lamina propria rather than lymphoid aggregate CD4 lymphocytes in HIV infection. Clin Exp Immunol 1997, 107:288-292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janoff EN, Jackson S, Wahl SM, Thomas K, Peterman JH, Smith PD: Intestinal mucosa immunoglobulins during human immunodeficiency virus type I infection. J Infect Dis 1994, 170:299-307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jackson S, Moldoveanu Z, Mestecky J, Pitts MA, Eldridge MH, McGhee JR, Miller C, Marx PA: Decreased IgA-producing cells in the gut of SIV-infected rhesus monkeys. Adv Exp Med Biol 1995, 371B:1035-1038 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Veazey RS, Rosenweig M, Shvetz DE, Pauley DE, DeMaria M, Chalifoux LV, Johnson RP, Lackner A: Characterization of gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) of normal rhesus macaques. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1997, 82:230-242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moghaddami M, Cummins A, Mayrhofer G: Lymphocyte-filled villi: comparison with other lymphoid aggregations in the mucosa of the human small intestine. Gastroenterology 1998, 115:1414-1425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Leary AD, Sweeney EC: Lymphoglandular complexes of the colon: structure and distribution. Histopathology 1986, 10:267-283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith PD, Fox CH, Masur H, Winter HS, Ailing DW: Quantitative analysis of mononuclear cells expressing human immunodeficiency virus type I RNA in esophageal mucosa. J Exp Med 1994, 180:1541-1546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang L, He T, Talal A, Wang G, Frankel SS, Ho DD: In vivo distribution of the human immunodeficiency virus/simian immunodeficiency virus coreceptors: CXCR4, CCR3, and CCR5. J Virol 1998, 72:5035-5045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Butcher EC, Picker LJ: Lymphocyte homing and homeostasis. Science 1996, 272:60-66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hussain LA, Lehner T: Comparative investigation of Langerhans cells and potential receptors for HIV in oral, genitourinary and rectal epithelia. Immunology 1995, 85:475-484 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McIntyre TM, Strober W: Gut-associated lymphoid tissue: regulation of IgA B cell development. ed 2 Ogra PL Mestecky J Lamm ME Strober W Bienenstock J McGhee J eds. Mucosal Immunology, 1999, :pp 319-356 Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cebra JJ, Shroff KE: Peyer’s patches as inductive sites for IgA commitment. Ogra PL Mestecky J Lamm ME Strober W Bienenstock J McGhee J eds. Handbook of Mucosal Immunology. 1994, :pp 151-158 Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neutra MR, Frey A, Kraehenbuhl JP: Epithelial M cells: gateways for mucosal infection and immunization. Cell 1996, 86:345-348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neutra MR: Interactions of viruses and microparticles with apical plasma membranes of M cells: implications for HIV transmission. J Infect Dis 1999, 179(Suppl 3):S441-S443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rott LS, Rose JR, Bass D, Williams MB, Greenberg HB, Butcher EC: Expression of mucosal homing receptor α4β7 by circulating CD4+ cells with memory for intestinal rotavirus. J Clin Invest 1997, 100:1204-1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Erle DJ, Briskin MJ, Butcher EC, Garcia-Pardo A, Lazarovits AI: Expression and function of MAC-CAM-1 receptor, integrin alpha 4 beta 7, on human leukocytes. J Immunol 1994, 153:517-528 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farstad IN, Halstensen TS, Lien B, Kilshaw PJ, Lazarovits AI, Brandtzaeg P: Distribution of beta 7 integrins in human intestinal mucosa and organized gut-associated lymphoid tissue. Immunology 1996, 89:227-237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andrew DP, Rott LS, Kilshaw PJ, Butcher EC: Distribution of α4β7 and αEβ7 integrins on thymocytes, intestinal epithelial lymphocytes and peripheral lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol 1996, 26:897-905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]