Abstract

Although placental development depends on careful coordination of trophoblast proliferation and differentiation, little is known about the mitotic regulators that are key to synchronizing these events. We immunolocalized a broad range of these regulators in tissue sections of the maternal-fetal interface (first trimester through term) that contained floating villi (which include cytotrophoblasts differentiating into syncytiotrophoblasts) and anchoring villi (which include cytotrophoblasts differentiating into invasive cells). Trophoblast populations at the maternal-fetal interface stained for 16 of the cell cycle regulators whose expression we studied. The staining patterns changed as a function of both differentiation and gestational age. Differentiation along the invasive pathway was associated with entrance into, then permanent withdrawal from, the cell cycle, as evidenced by the orchestrated expression of cyclins, their catalytic subunits, and inhibitors. Surprisingly, we found coexpression of molecules that regulate different portions of the cell cycle in the syncytium. These data, which constitute one of the few examples to date of in situ localization of an extensive repertoire of mitotic regulators, provide the basis for studies aimed at understanding factors that lead to abnormal placentation.

The placenta, which forms the interface between the embryo/fetus and the mother, is a critical determinant of pregnancy outcome. A great deal of information about its unique architecture and functions has come from studies that use biopsy specimens of the maternal-fetal interface. 1 The placenta, the fetal portion of this interface, is the first organ to function during development. In parallel, the uterine lining or placental bed, the maternal portion of this interface, undergoes extensive remodeling. 1-4

The human placenta’s unique anatomy is due in large part to differentiation of its epithelial stem cells, termed cytotrophoblasts (CTBs). 5 How these cells differentiate determines whether chorionic villi, the placenta’s functional units, float in maternal blood or anchor the conceptus to the uterine wall. In floating villi, CTB stem cells (referred to here as villus CTBs or vCTBs) differentiate by fusing to form multinucleated syncytiotrophoblasts (STBs) whose primary function, transport, is ideally suited to their location at the villus surface. In anchoring villi, CTB stem cells also fuse, but many remain as single cells that detach from their basement membrane and form aggregates termed cell columns. CTBs at the distal ends of these columns attach to and then deeply invade the uterus (interstitial invasion) and its vessels (endovascular invasion). Interestingly, endovascular invasion is more extensive on the arterial than the venous side. During this process CTBs replace the endothelial and muscular lining of uterine vessels, a process that greatly enlarges the diameter of arterioles, initiates maternal blood flow to the placenta, and permits venous return to the maternal circulation. As in most organs, the placenta retains a pool of undifferentiated stem cells that are evident even at term. Whether they can compensate for placental damage by differentiating later in gestation is an interesting possibility that has been hard to prove.

Some of the molecular mechanisms that govern human CTB differentiation and invasion are well understood. These include an upstream suite of transcriptional regulators such as Mash-2, 6 Hand1, 7,8 and Gcm1, 9,10 and a downstream set of effectors such as adhesion molecules, 11 proteinases, 12 and the trophoblast major histocompatibility antigen HLA-G. 13,14 In comparison, much less is known about how CTB proliferation is coordinated with differentiation. Although reagents, including many antibodies, are available for studying the expression of cell cycle regulators in tissue sections, few published studies have broadly used this approach to localize markers that are specifically expressed during key transitions and phases. This information, in conjunction with the extensive mechanistic insights that have been obtained about the biochemical roles of cell cycle regulators, 15 could be very informative.

Although a few markers have been localized, 16-18 it is not surprising that CTB progression through and exit from the cell cycle as a function of differentiation have not been systematically studied. Based on mitotic index, 19 it is now well established that vCTBs are placental stem cells. 20,21 In addition to vCTBs, proliferative cells that express S phase markers are also detected in the proximal portions of cell columns associated with anchoring villi. 22-24 Immunostaining of first trimester placental bed biopsy specimens with an antibody against the Ki67 antigen, which is expressed by cells that are synthesizing DNA, revealed that its expression abruptly stops at sites where CTBs differentiate and attach to the uterine wall. Together, these data suggest that differentiation of invasive CTBs is coordinated with exit from the cell cycle. 25 The expression patterns of G1 and G2 cyclins and of their cyclin-dependant kinases (CDKs) further support this hypothesis. 17

To test this hypothesis, we immunolocalized markers that are specifically expressed during all of the key transitions and phases of the cell cycle in tissue sections of the maternal-fetal interface. The results showed that as CTBs differentiate/invade, they down-regulate the expression of molecules that are associated with mitosis and up-regulate the expression of a number of inhibitors that engineer permanent withdrawal from the cell cycle. In contrast, multinucleate STBs coexpressed an unusual repertoire of markers that are usually segregated to distinct portions of the cell cycle. We also saw interesting gestation-related changes. By the second trimester, many fewer CTB stem cells and cells in columns expressed mitotic markers. There was a reciprocal increase in the number of column CTBs that expressed inhibitors. Together, these data suggest that CTB proliferation, like differentiation, is part of a developmental program that is timed to precede development of the embryo/fetus.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Sources

Chorionic villi with attached decidua were collected immediately after elective pregnancy terminations for nonmedical reasons or after spontaneous deliveries. Because of their relatively small size, every sample from each first trimester placenta was processed. Second and third trimester samples were from three to five randomly chosen sites. None of the placentas had abnormalities that could be detected either grossly or histologically. Tissues were obtained from women whose pregnancies were terminated at 8 to 10 weeks (3 samples), 15 to 17 weeks (7 samples), or 20 weeks of gestation (5 samples). Fifteen samples were obtained at the time of normal term delivery (38–40 weeks of gestation). Conclusions were based on analysis of all samples in each group.

Antibodies

Antibodies were obtained from the following sources. Mouse monoclonal anti-cyclin D1, -cyclin D2, -cyclin D3, -p21, -p16, and -Mdm2, and rabbit polyclonal anti-cyclin E (C-19), -CDK4, -CDK6, -Cdc2, -p57, and -p27 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-specific p53 was purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA). Mouse monoclonal anti-p53 and -cyclin A were from Oncogene Research Products (Cambridge, MA). Mouse monoclonal anti-cyclin D2, -cyclin B, and -pRb were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-histone 3 was from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). Mouse monoclonal anti-Ki67 was purchased from DAKO (Carpinteria, CA). The rat anti-human cytokeratin (CK) monoclonal antibody (7D3) was produced by the Fisher laboratory. 11 Rhodamine- and fluorescein-labeled goat anti-mouse, -rat, and -rabbit IgG were obtained from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, Inc. (West Grove, PA). The specificities of antibodies that had not been previously used for immunolocalization were studied further. These included anti-cyclin D1, -cyclin B, -p21, -Mdm2, -p57, -p27, and -pRb, whose reactivity with a band of the expected molecular weight was confirmed by immunoblotting samples of electrophoretically separated human chorionic villi and purified CTB lysates as previously described. 25

Immunofluorescence Localization

Placental tissues were processed for double indirect immunolocalization as previously described. 26-29 Nuclei in these sections were visualized by staining with Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Briefly, tissues were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes, washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), infiltrated with 5 to 15% sucrose followed by Optimal Cutting Temperature compound (Miles Scientific, Naperville, IL), and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Sections (6 μm) were prepared using a cryostat (Slee International Inc., Tiverton, RI) and collected on poly-L-lysine-coated microscope slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Fixed sections were permeabilized in cold methanol for 5 minutes, washed three times in PBS for 5 minutes, and incubated for 30 minutes with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in PBS. Sections were then incubated for 1 hour with two primary antibodies (7D3 to detect trophoblasts and one that specifically reacted with a cell cycle regulator) followed by rinsing three times in PBS for 5 minutes. The sections were then incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated to rhodamine or fluorescein and washed three times in PBS for 5 minutes. Afterward, tissue sections were placed in the Hoechst dye (10 μg/ml PBS) for 2 minutes, washed in PBS (5 minutes), and mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). All incubations and washes were performed at room temperature. Negative controls were included in every experiment. Either pre- or non-immune serum was always used for this purpose. Other controls included isotype-matched non-immune serum and omission of the primary antibody. In no instance was staining observed in the negative controls. Samples were examined with a Zeiss Axiophot epifluorescence microscope (Thornwood, NY) equipped with filters to selectively view the rhodamine and fluorescein fluorescence. Hoechst staining was photographed under ultraviolet illumination.

Staining was evaluated as follows. In most cases trophoblast nuclei, as confirmed by Hoechst staining, either stained brightly or failed to react with an antibody. The only exception was anti-cyclin-D3, which showed faint reactivity. The fact that these antibodies strongly stained nuclei in human cell lines suggested that the patterns we observed were correct. Therefore, intensity of staining was not quantified. In contrast, there was a great deal of variation in the number of cells in different regions that reacted with all of the other antibodies. As a result the number of antibody-reactive cells was graded according to the following semiquantitative scale of percentage of CK-positive cells showing reactivity: +++, more than 75%; ++, 50 to 74%; +, 25 to 49%; +/−, 5 to 24%; −, less than 5%. Unless otherwise noted, the same results were obtained for samples of all gestational ages within a group.

Results

Starting with G1, we immunolocalized cell cycle regulators in tissue sections of the maternal-fetal interface that contained floating villi (which include CTBs differentiating into syncytium) or anchoring villi (which include CTBs differentiating into invasive cells, and often the site of uterine attachment). The tissue sections were double-stained with anti-cytokeratin, which specifically reacts with all populations of trophoblast cells. The results obtained from analysis of first and second trimester tissues are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 ▶ ▶ , respectively. We focused on these stages because much placental development occurs during this period. Accordingly, proper coordination of CTB proliferation and differentiation during this time is a crucial determinant of pregnancy outcome.

Table 1.

First Trimester Staining Patterns of Cell Cycle Regulators at the Fetal-Maternal Interface

| Cell cycle phase | Marker* | Placenta—fetal side | Uterine wall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syncytiotrophoblast | Cytotrophoblast cells (CTBs) | ||||||

| Villus CTBs | Cell column CTBs | Invasive CTBs | |||||

| Proximal | Distal | Superficial | Deep | ||||

| G1 | Cyclin D1 | − | +++ | + | + | − | − |

| Cyclin D3† | − | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | |

| CDK4 | − | +++ | ++ | − | − | − | |

| CDK6 | − | +/− | − | − | − | − | |

| p16 | − | − | − | +/− | +++ | − | |

| G1-S | p21 | − | + | + | + | ++ | − |

| p27 | − | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | |

| p57 | − | + | − | + | +++ | +++ | |

| P-p53† | − | − | +/− | +/− | − | − | |

| Mdm2 | − | +++ | ++ | ++ | − | − | |

| S | Ki67 | − | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | − |

| Cyclin A | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | |

| G2-M | Cyclin B | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | − |

| Cdc2 | − | +++ | ++ | +/− | − | − | |

| M | Histone P-H3 | − | +/− | +/− | + | +++ | − |

Immunostaining was scored on a semiquantitative scale as described in Materials and Methods. Results ranged from +++ (≥75% of cells stained) to − (≤5% of cells stained).

*No immunostaining was observed for cyclin D2, pRb, or unphosphorylated p53.

†Cytoplasmic staining.

Table 2.

Second Trimester Staining Patterns of Cell Cycle Regulators at the Fetal-Maternal Interface

| Cell cycle phase | Marker* | Placenta—fetal side | Uterine wall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syncytiotrophoblast | Cytotrophoblast cells (CTBs) | ||||||

| Villus CTBs | Cell column CTBs | Invasive CTBs | |||||

| Proximal | Distal | Superficial | Deep | ||||

| G1 | Cyclin D1 | − | + | +/−, −† | − | − | − |

| Cyclin D3 | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| CDK4 | − | ++ | + | − | − | − | |

| CDK6 | − | ++ | + | − | − | − | |

| p16 | ++ | ++, +++‡ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |

| G1-S | p21 | − | +/− | +/− | − | − | − |

| p27 | − | +/− | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | |

| p57 | −, ++§ | ++ | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | |

| P-p53 | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Mdm2 | − | + | + | + | − | − | |

| S | Ki67 | − | ++ | + | − | − | − |

| Cyclin A | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | − | |

| G2-M | Cyclin B | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| Cdc2 | − | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | |

| M | Histone P-H3 | − | +/− | +/− | +/− | +/− | − |

Immunostaining was scored on a semiquantitative scale as described in Materials and Methods. Results ranged from +++ (≥75% of cells stained) to − (≤5% of cells stained).

*No immunostaining was observed for cyclin D2, pRb or unphosphorylated p53.

†+/−, 15 weeks; −, 20 weeks

‡++, 15 weeks; +++, 20 weeks

§−, ≤15 weeks; ++, ≥20 weeks

To begin mapping CTB progression through G1, we used antibodies to localize expression of D-type cyclins, together with their catalytic subunits, CDK4 and CDK6. The D-type cyclins serve as growth factor sensors that integrate extracellular signals with the cell cycle machinery. Together with their partner kinases, CDK4 and 6, they operate in early-to-mid G1 to promote progression through the G1-S restriction point. Thus their expression signals the cell’s commitment to replicate its genome. 30,31 Because these cyclin proteins have a very short half life (20 to 30 minutes), their protein levels are directly related to the rate of transcription. 32 Thus, staining patterns primarily identify cells in G1.

Staining for cyclin D1 showed very specific expression patterns in both first and second trimester tissues. In first trimester samples most cells of the vCTB monolayer and about 25% of CTBs in cell columns (Figure 1A) ▶ reacted with the antibody. In both cases predominantly nuclear staining was observed. In the latter case patches of CTBs stained. Less frequently, cells in the villus core also reacted with anti-cyclin D1. The STB layer (Figure 1A) ▶ and CTBs in the uterine wall (data not shown) did not stain for cyclin D1. In second trimester samples, a much lower percentage of the vCTB monolayer stained. Sometimes a few stained cells in the proximal column regions were observed in very early second trimester samples (eg, 15 weeks of gestation). At 20 weeks, cells in the column no longer stained (Figure 1C) ▶ . In the second trimester, we observed no staining of invasive CTBs within the uterine wall (data not shown) or of the syncytium (Figure 1C) ▶ .

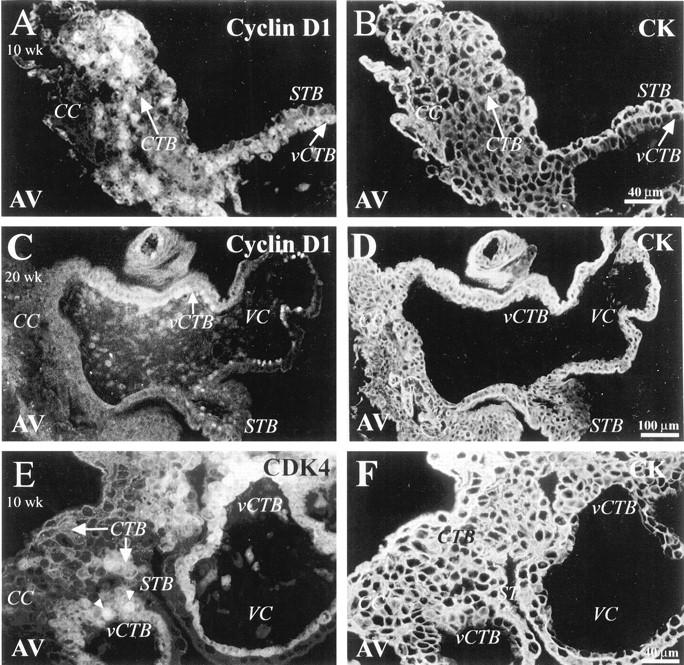

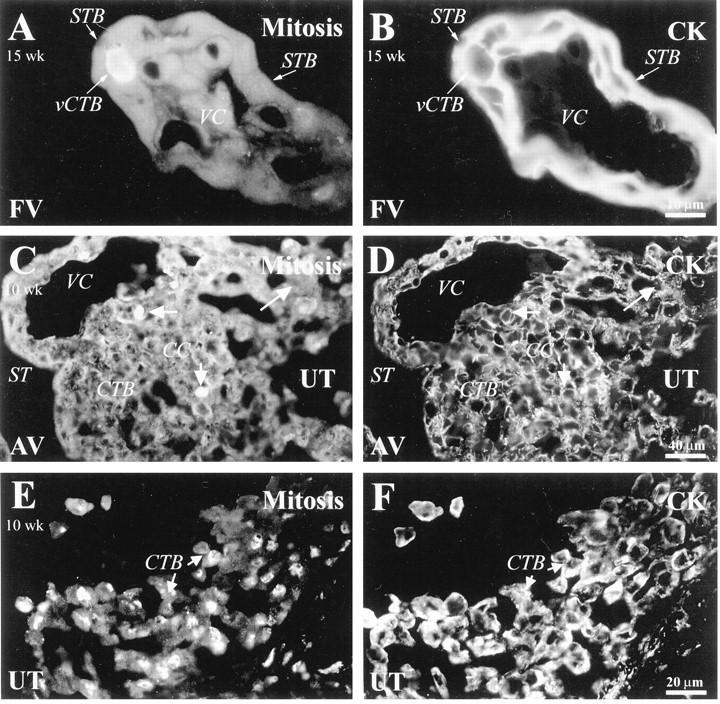

Figure 1.

Nuclear staining for cyclin D1 and its catalytic subunit CDK4 is detected in association with villus cytotrophoblasts and cytotrophoblasts in columns. Tissue sections that contained 10-week (A, B, E, F) and 20-week (C and D) anchoring villi were double stained with anti-cyclin D1 (A and C) or anti-CDK4 (E) and with anti-cytokeratin (CK) to mark cytotrophoblasts (CTB) (B, D, F). A: In anchoring villi (AV) from first trimester tissue, cyclin D staining was detected in association with the nuclei of villus CTBs (vCTB) and of CTBs (arrow) in cell columns (CC). C: At 20 weeks of gestation cyclin D1 expression was detected only in vCTBs and not in cell columns. A and C: Syncytiotrophoblasts (STB) did not stain for cyclin D1. E: Anti-CDK4 labeled vCTBs and column CTBs in 10-week samples. Staining was both nuclear (arrowheads) and cytoplasmic (arrows). VC, villus core.

To determine the degree of overlapping expression among the D-type cyclins, we also assessed the staining patterns of antibodies specific for cyclins D2 and D3, molecules that may play a role in cell proliferation or maintenance of terminal differentiation. 33 None of the trophoblast populations stained for cyclin D2, either in first or in second trimester samples (summarized in footnote to tables; data not shown). In first trimester tissue, anti-cyclin D3 failed to stain STBs, but did react with a substantial number of vCTBs and CTBs in the proximal region of cell columns. A cytoplasmic rather than a nuclear staining pattern was observed (data not shown). Because functionally active cyclins localize to the nucleus, the significance of this result was unclear. In second trimester tissue, anti-cyclin D3 did not stain any of the trophoblast populations (data not shown).

We also examined the expression of CDK4, a catalytic partner of D-type cyclins. In first trimester samples, both nuclear and cytoplasmic staining were detected (Figure 1E) ▶ , essentially in the same pattern as cyclin D1 expression; no staining for CDK4 was detected in CTBs past the mid-column region (data not shown). The same pattern was observed in second trimester samples, except that fewer vCTBs stained (data not shown). As to immunolocalization of CDK6, staining of first trimester samples was sometimes observed. Antibody reactivity was confined to a few vCTBs. In second trimester tissue CDK6 staining resembled that of CDK4 (data not shown); antibody-reactive cells were observed among the vCTB and proximal column populations.

Next, we localized cyclin E expression. Levels of this cyclin peak at the G1-S transition, ie, later than the D-type cyclins. Cyclin E associates with CDK2. The peak of the associated kinase activity, which also occurs during late G1, is required for progression into S phase. 34 After a cell enters S phase, cyclin E is rapidly degraded, which frees CDK2 to associate with cyclin A.

In general, we observed strong nuclear reactivity with anti-cyclin E in all CTBs (data not shown). Normally, cyclin E is expressed at the G1-S transition. However, we found cyclin E is coexpressed with cyclins that mark S and G2 (eg, cyclins A and D; see below). In light of this discrepancy, we could not interpret this staining pattern.

To understand how CDKs promote cell cycle progression, it is important to identify their physiological substrates. Cyclin D-CDK4/6, cyclin E-CDK2, and cyclin A-CDK2 complexes have been implicated in sequential phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein (pRb). Phosphorylation of pRb releases E2F and other transcription factors that trigger the activation of S-phase (such as cyclin A 35 ) and regulates the restriction point of “start” for cell cycle progression. 30,36 Staining of first and second trimester tissue samples for pRb was so weak that no obvious pattern could be discerned. Because commercially available antibodies do not discriminate between the phosphorylated (inactive) and nonphosphorylated (active) forms of pRb, this line of investigation was not pursued.

In addition to cyclin binding, the activity of the G1 cyclin-CDKs is regulated by specific cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CDKIs). CDKIs belong to two families that are differentiated by their targets. The INK4 family includes p15, p16, p18, and p19, which specifically inhibit the activity of CDK4/6 complexes. 37

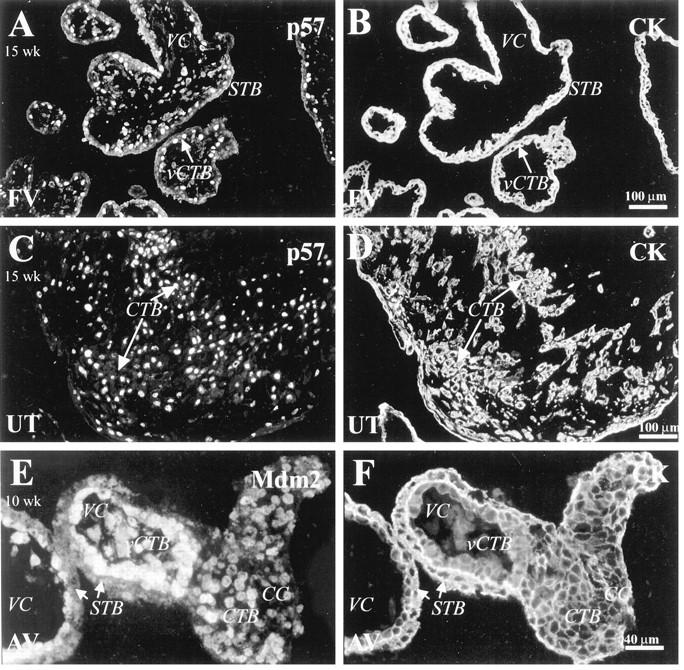

In first trimester tissue anchoring villi, nuclear staining for p16, the most specific inhibitor of CDK4 and CDK6, was confined to a few CTBs in the distal region of cell columns (Figure 2A) ▶ . Interestingly, most CTBs within the uterine wall expressed p16 (Figure 2C) ▶ . In second trimester tissue, staining for p16 was significantly up-regulated in association with STBs, vCTBs (Figure 3A) ▶ and column CTBs, in both the proximal and the distal regions (Figure 3C) ▶ . Most CTBs in all areas of the uterine wall stained for p16 (Figure 3C) ▶ .

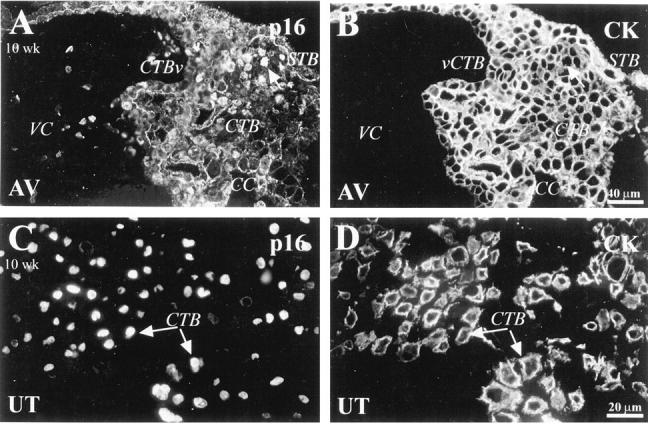

Figure 2.

Immunostaining for p16 in first trimester placentas was primarily localized to invasive cytotrophoblasts. A-D: Sections of 10-week placental bed tissue were double stained with anti-p16 (A and C) and anti-CK (B and D). A: Nuclear staining for p16 was detected in association with the nuclei of a few cytotrophoblasts (CTB; arrow) located in the distal portions of cell columns (CC). C: The nuclei of most invasive CTBs in the uterine wall (UT) also stained. VC, villus core; vCTB, villus CTB; STB, syncytiotrophoblast; AV, anchoring villi.

Figure 3.

In second trimester samples, p16 was expressed by many trophoblasts in all locations. Sections of 15-week floating (A and B) and anchoring (C and D) villi and the portion of the uterine wall to which they attached (C and D) were double stained with anti-p16 (A and C) and anti-CK (B and D). A and C: Prominent p16 staining, in a nuclear pattern, was detected in association with villus CTBs (vCTB), syncytiotrophoblasts (STB), and CTBs in cell columns (CC). C: Staining for p16 was also detected in association with cytotrophoblasts within the uterine wall (UT). FV, floating villi; AV, anchoring villi; VC, villus core.

In comparison to INK4 family members, the actions of Cip/Kip kinase inhibitors are less specific. 38-40 Family members include p21 (whose expression we previously studied at a biochemical level 25 ), p27, and p57. Expression of p21 is correlated with cell cycle arrest before terminal differentiation. 41 However, there are also a number of examples of p21 induction in association with cell cycle progression. 42-44 p27 is reported to inhibit cyclin D1-CDK4 activity and to modulate the actions of the cyclin D3-CDK4 complex by altering its substrate specificity. 45 Additionally, expression of p27 is stimulated by differentiation-promoting agents in vitro 46 and during differentiation in vivo. 47,48 It is interesting that in addition to their role as inhibitors, both p21 and p27 can be found in active kinase complexes of proliferating cells. 49,50 p57, a potent inhibitor of several cyclin-CDK complexes, is primarily expressed in terminally differentiated cells. 40

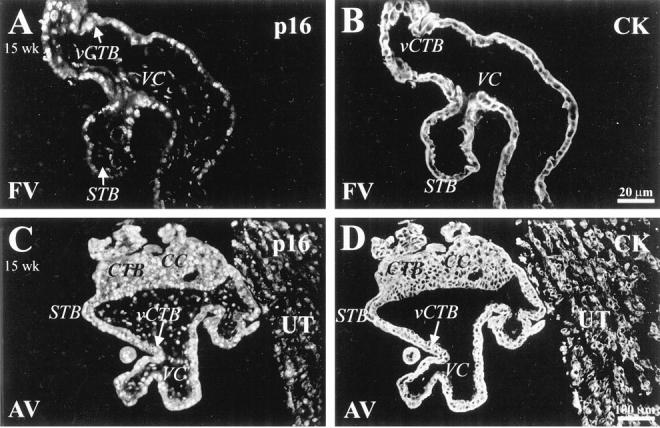

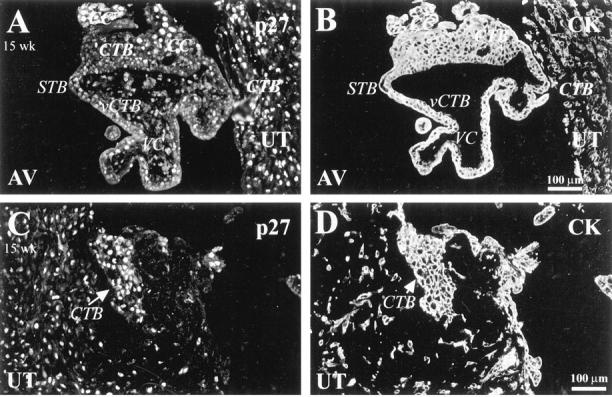

We found that the staining pattern for p21 changed with gestational age. In first trimester samples, about 25% of vCTBs and CTBs throughout the column reacted with the antibody (data not shown). More than 50% of CTBs in the superficial decidua also stained. In second trimester samples, fewer vCTBs and proximal column CTBs stained. No staining of CTBs within the decidua was observed. As for p27, STBs in first and second trimester samples failed to react with the antibody (eg, 15 weeks of gestation; Figure 4A ▶ ). In first trimester samples, anti-p27 stained the nuclei of ∼25% of vCTBs and CTBs in columns. A larger percentage of CTBs within the uterine wall also stained (data not shown). In second trimester samples, anti-p27 reacted with the nuclei of a few vCTBs and CTBs throughout cell columns (Figure 4A) ▶ . Most invasive CTBs within the uterine wall stained (Figure 4C) ▶ . In general, a greater percentage of CTBs stained in second than in first trimester samples. Immunolocalization of p57 showed a pattern similar to that of anti-p27 staining in both first (data not shown) and second trimester (Figure 5, A and C) ▶ samples. The only exception was STB staining, which was observed only at 20 weeks of gestation (data not shown).

Figure 4.

p27 staining correlated positively with cytotrophoblast differentiation along the invasive pathway. A-D: Sections of 15-week placental bed were double stained with anti-p27 (A and C) and with anti-CK (B and D). Anti-p27 stained the nuclei of some villus CTBs (vCTB), more CTBs in the distal portions of cell columns (CC) (A), and most invasive CTBs within the uterine wall (UT) (A and C). AV, anchoring villi; STB, syncytiotrophoblast; VC, villus core.

Figure 5.

Trophoblasts stained with anti-p57 and anti-Mdm2. Tissue sections from first and second trimester samples were double stained with anti-p57 (A and C) or anti-Mdm2 (E) and with anti-CK (B, D, F). A and C: p57 staining of 15-week tissue showed that many villus CTBs (vCTB) reacted with the antibody (A), as did most of invasive CTBs within the uterine wall (UT) (C). E: In 10-week placental tissue, most villus CTBs stained with anti-Mdm2. A slightly lower percentage of CTBs throughout cell columns (CC) also stained. STB, syncytiotrophoblast; VC, villus core; FV, floating villi; AV, anchoring villi.

The p53 tumor-suppressor protein is another very important transcription factor that is required for transactivation of a number of genes involved in growth control 51 and in cell cycle progression in response to various types of stress. 52 In response to DNA damage, p53 induces cell cycle arrest by triggering the synthesis of the CDK inhibitor p21. 53 The p53 protein, which is short-lived, is maintained at low levels in normal cells.

We observed no staining for nonphosphorylated p53. Staining (cytoplasmic, confined to columns) for the phosphorylated form of p53 was either weak or absent in first and second trimester tissue samples, respectively (data not shown). In contrast to p53, staining for the Mdm2 oncoprotein, a potent p53 inhibitor, 54,55 was observed in many vCTBs and CTBs throughout cell columns in first trimester tissue samples (Figure 5E) ▶ . No other trophoblast populations stained. The same pattern was observed in second trimester samples except that a lower percentage of cells stained (data not shown).

The Ki67 antigen is commonly used for in situ detection of cells in S phase. 56 We previously immunolocalized this marker in samples of first trimester chorionic villi. 25 The results showed that staining was confined to villus and column CTBs and that most of these cells stained. Ki67 expression was abruptly down-regulated as CTBs invaded the uterine wall. Essentially, the same staining pattern was observed in second trimester tissue samples, except that fewer vCTBs and CTBs in the proximal column stained; CTBs in the distal column region were negative (data not shown).

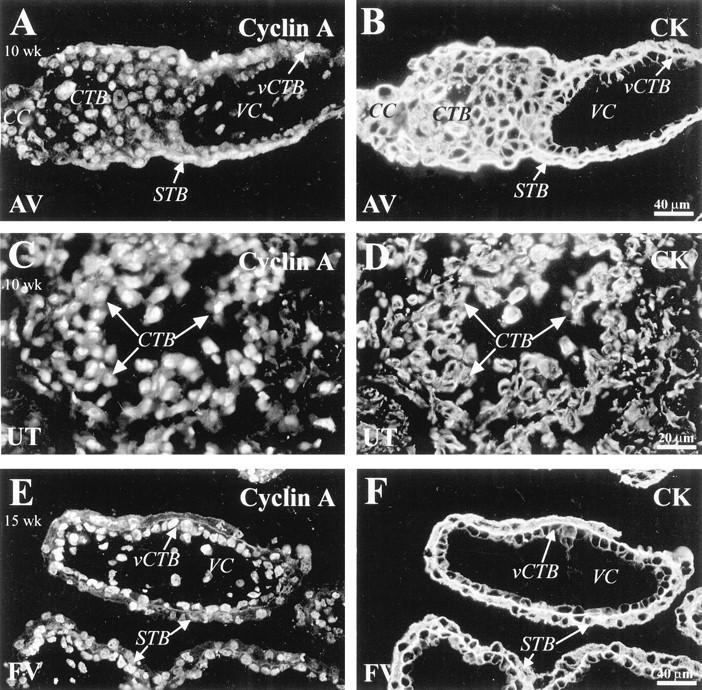

Next, we examined expression of cell cycle regulators that govern progression from S phase to mitosis. During progression from G1 to S, cyclin A acts synergistically with cyclin E-CDK2 to initiate DNA replication. 57 During S phase, cyclin A is transported to the nucleus where it binds Cdc2, generating a peak of activity in G2 before it is abruptly degraded early in M phase. 58

Immunolocalization with an antibody specific for cyclin A showed that this cell cycle regulator was broadly expressed. In first trimester tissue, STBs, vCTBs, most CTBs in columns, and CTBs near the surface of the uterine wall stained brightly (Figure 6, A and C) ▶ . In contrast, CTBs that invaded more deeply failed to stain (data not shown). A similar pattern was observed in second trimester tissue samples, but fewer cells reacted with the antibody. Many of the nuclei of vCTBs and the syncytium stained (Figure 6E) ▶ , as did CTBs in cell columns and superficial decidua; CTBs within the deeper portions of the uterine wall did not (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Staining for cyclin A was detected in association with most trophoblast populations. Sections of 10-week (A-D) and 15-week (E and F) tissues were double stained with anti-CK (B, D, F) and anti-cyclin A (A, C, E). A: In first trimester tissue, anti-cyclin A stained syncytiotrophoblasts (STB), villus CTBs (vCTB), and CTBs in cell columns (CC). C: Also in first trimester tissue, most of the CTBs near the surface of the uterine wall (UT) stained, but those deeper in the decidua did not (data not shown). E: Sections of 15-week floating villi (FV) showed that many vCTBs and STBs stained with anti-cyclin A. VC, villus core.

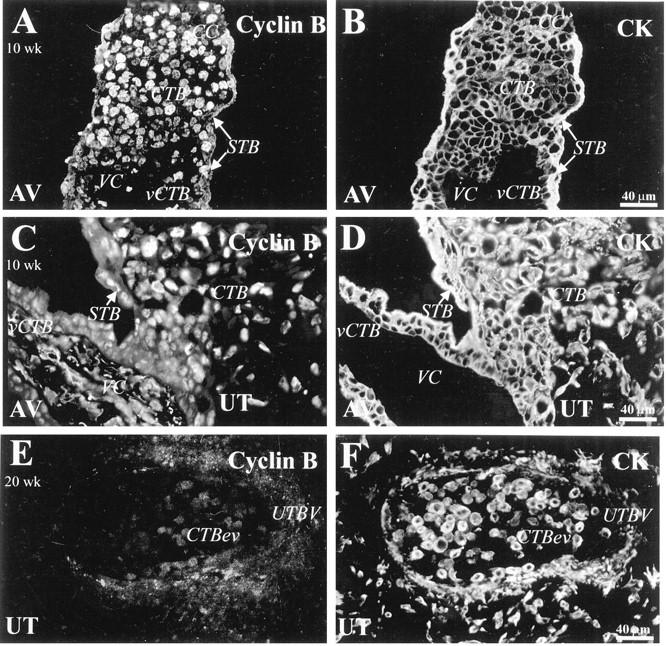

Two cyclin-CDK complexes function by reorganizing cells for mitosis: cyclin A-Cdc2 and cyclin B-Cdc2. The active cyclin B-Cdc2 complex initiates many events that are critical to mitosis. 59 During G1, S, and G2, cyclin B localizes to the cytoplasm. With progression toward M, cyclin B accumulates in the nucleus. When the nuclear envelope breaks down, this cyclin relocalizes from the nuclear matrix to the centrosomes and subsequently to the mitotic spindle. 58

In first trimester tissue samples, anti-cyclin B stained the nuclei of STBs, vCTBs, and column CTBs (Figure 7A) ▶ . Many invasive CTBs, only in the superficial region of the uterine wall, also stained with anti-cyclin B (Figure 7C) ▶ . A similar pattern of cyclin B expression was seen in second trimester tissue, except that many fewer CTBs in all locations stained and invasive CTBs failed to react with the antibody (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Staining for cyclin B, which was detected in association with CTBs in cell columns and within the uterine wall, was absent on endovascular CTBs. Tissue sections from first (10-week; A-D) and second trimester (20-week; E and F) samples were double-stained with anti-cyclin B (A, C, E) and with anti-CK (B, D, F). A and C: In first trimester tissue, anti-cyclin B stained the nuclei of villus CTBs (vCTB), column (CC) CTBs and syncytiotrophoblasts (STB). C: Many invasive CTBs in the superficial region of the uterine wall (UT) also stained with anti-cyclin B. E: A section of the uterus (UT) at 20 weeks that contained a blood vessel (UTBV) showed that endovascular CTBs (CTBev) failed to stain with anti-cyclin B. AV, anchoring villi; VC, villus core.

Because tissue sections that contain maternal spiral arterioles that have been modified by invasive CTBs are difficult to obtain, we could not fully analyze expression of cell cycle markers by endovascular trophoblasts. However, we did obtain information on their cyclin expression. In all cases no staining for D-type cyclins (data not shown), cyclin A (data not shown), or cyclin B (Figure 7E) ▶ was detected. In this regard the cells’ phenotype was similar to that of CTBs in the deep interstitium of the uterus.

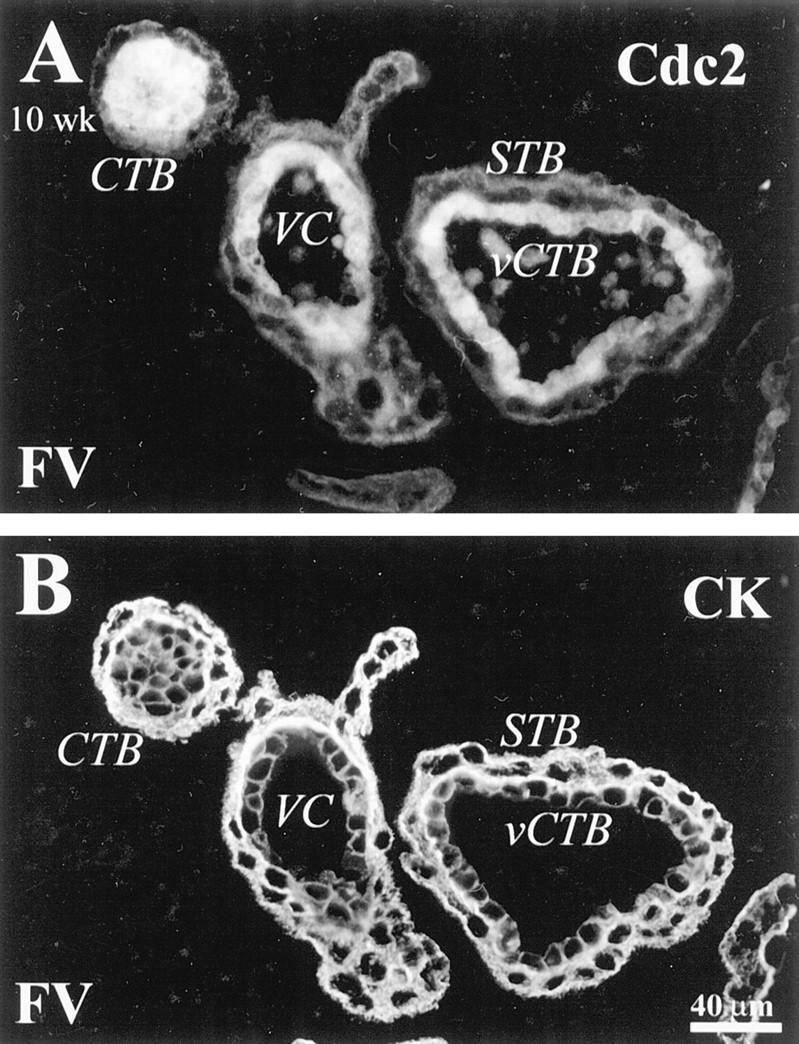

Association of cyclin B with the Cdc2 kinase is critical for progression through M phase. 60 To confirm that cyclin B and Cdc2 are coexpressed in trophoblasts, we also immunolocalized the latter marker in tissue sections from first and second trimester tissue samples. In both sets of samples, the nuclei and cytoplasm of many vCTBs (Figure 8A) ▶ and CTBs in the proximal column (data not shown) stained brightly. A few CTBs in the distal column region of some first trimester samples showed reactivity; no staining of cells in this region was observed in second trimester tissue. The STB layer (Figure 8A) ▶ and invasive CTBs did not stain for Cdc2 (data not shown).

Figure 8.

In first trimester samples, staining for the cyclin B-associated kinase Cdc2 was detected in association with villus CTBs. Sections of floating villi (FV) were double stained with anti-CK (B) and anti-Cdc2 antibodies (A). Cdc2 staining was detected in association with the nuclei and cytoplasm of villus CTBs (vCTB). CTBs in the proximal column region also stained (data not shown). VC, villus core; STB, syncytiotrophoblast.

To confirm that CTBs complete mitosis as they differentiate, we stained sections of the maternal-fetal interface with an antibody against the phosphorylated form of histone H3. Phosphorylation of H3 histone is involved in chromatin condensation during mitosis. 61 Accordingly, this antibody specifically labels cells in M phase.

In both first (data not shown) and second trimester villi (Figure 9A) ▶ , 5 to 10% of vCTBs stained with an antibody that recognized histone H3. These data suggest that vCTBs continue to divide throughout the first half of gestation and support the concept that they are stem cells. 20,21 In first trimester tissue samples, immunoreactive CTBs were found throughout the cell column (Figure 9C) ▶ and in the superficial portion of the uterine wall (Figure 9E) ▶ . Strikingly, the majority of cells in M phase were found within the superficial decidua. In second trimester samples, staining was restricted to a few cells in the columns and in the superficial regions of the uterus (data not shown).

Figure 9.

Cytotrophoblasts in M phase were detected at the maternal-fetal interface. Sections of 10-week (C−F) and 15-week (A and B) placental tissue were double stained with anti-histone H3 (A, C, E) to detect cells in M phase and with anti-CK (B, D, F). Antibody reactivity was detected among villus CTBs (vCTB; A) and CTBs in columns (C). E: Of all of the compartments examined, the highest number of CTBs in M phase were found in the superficial portion of the uterine wall (UT). FV, floating villi; AV, anchoring villi; VC, villus core; STB, syncytiotrophoblast.

Finally, we examined expression of all of the foregoing markers in third trimester samples (Table 3) ▶ . As expected, the term vCTB layer was incomplete and greatly diminished in cell number. The most striking difference from first and second trimester samples was the degree of variation between staining patterns of different placentas. There were also striking variations in vCTB expression of cell cycle markers in different regions of individual placentas. The most prominent feature of these cells was their strong and relatively uniform staining for inhibitors. For example, staining for p21 and p27 was up-regulated as compared to early gestation samples. However, each placenta also contained regions in which vCTBs expressed markers of all phases of the cell cycle. These vCTBs, usually found in clusters, had a staining pattern that was essentially indistinguishable from that observed in both first and second trimester samples. Most frequently, these cells expressed M phase markers such as cyclin B and histone H3. In contrast, Mdm2-positive cells, which are candidates for contributing to the stem cell population, were randomly distributed (approximately 1–5 cells per field).

Table 3.

Third Trimester Staining Patterns of Cell Cycle Regulators at the Fetal-Maternal Interface

| Cell cycle phase | Marker* | Placenta—fetal side | Uterine wall | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syncytiotrophoblast | Cytotrophoblast cells (CTBs) | ||||

| Villus CTBs | Invasive CTBs | ||||

| Superficial | Deep | ||||

| G1 | Cyclin D1 | − | +/−† | − | − |

| Cyclin D3 | − | − | − | − | |

| CDK4 | − | +/− | − | − | |

| CDK6 | − | − | − | − | |

| p16 | − | +/− | − | +++ | |

| G1-S | p21 | +/− | +/− | − | +/− |

| p27 | + | +/− | +++ | +++ | |

| p57 | +/− | ++ | +++ | +++ | |

| P-p53 | − | − | − | − | |

| Mdm2 | − | + | − | − | |

| S | Ki67 | − | + | − | − |

| Cyclin A | +/− | + | + | − | |

| G2-M | Cyclin B | + | + | +/− | − |

| Cdc2 | − | + | − | − | |

| M | Histone P-H3 | − | + | +/− | − |

Immunostaining was scored on a semiquantitative scale as described in Materials and Methods. Results ranged from +++ (≥75% of cells stained) to − (≤5% of cells stained).

*No immunostaining was observed for cyclin D2, pRb or unphosphorylated p53.

†+/−, Results varied (from + to −) between and within different regions of placentas.

As expected, columns of anchoring villi are largely depleted of cytotrophoblasts at term. Thus, they were greatly shortened as compared to those observed in early gestation which made them relatively harder to identify. Accordingly, data on this population of cells were not included in Table 3 ▶ . Nevertheless, it was interesting to note that the few column cytotrophoblasts that remained expressed a repertoire of cell cycle markers that was essentially indistinguishable from the pattern observed earlier in gestation. For example, CTBs at attachment sites stained with antibodies against cyclin A, cyclin B, and Cdc2; a few cells in mitosis were also observed, as evidenced by staining with anti-histone H3.

Discussion

Placental growth depends on CTB proliferation. A portion of CTBs, which retain an undifferentiated phenotype throughout pregnancy, provide a reservoir of stem cells. The remaining CTBs give rise to the two major trophoblast subpopulations, STBs and invasive CTBs. Here we mapped cell cycle progression in both populations with the goal of understanding the mechanisms that maintain a pool of vCTB stem cells and govern CTB exit from the cell cycle during differentiation along the invasive pathway. We were also very interested in the repertoire of cycle regulators that multinucleated STBs express.

We were particularly interested in the percentage of vCTBs that expressed all markers of cell cycle progression from G1 to M and did not express inhibitors of cyclin-CDK activity. Presumably these are stem cells. This pool was bigger in the first (≥50% of CTBs) than in the second (≤25% of CTBs) trimester. A further decline was noted at term (1–5% of CTBs), although a small proportion of CTBs retained the ability to proliferate until the end of pregnancy. These data are consistent with previous reports. 23 At all stages of gestation some vCTBs showed positive staining for the CDK inhibitors p16, p21, and p57. In general the percentage of CTBs that expressed inhibitors correlated positively with increased gestational age. We speculate that this population is composed of differentiating CTBs.

The most surprising and novel finding in first trimester samples was the expression of the Mdm2 oncoprotein in the nuclei of ≥75% of vCTBs. In CTBs Mdm2 was coexpressed with cyclins D1, A, and B, and with Cdc2. Mdm2 inhibits p53-mediated cell cycle arrest and apoptotic functions, 55,62 and overexpression of Mdm2 can reduce the amount of endogenous p53. Consistent with the role of Mdm2 as a p53 inhibitor, 63 we found that high expression of Mdm2 correlated with lack of staining for p53. In addition, Mdm2 relieves the proliferative block mediated by either p53 or pRb and promotes proliferation by stimulating the S-phase-inducing transcriptional activity of E2F. 64 We hypothesize that Mdm2 may be one of the factors that maintain the pool of proliferating stem cells in the placenta. The observed decrease in Mdm2 expression in second and third trimester tissue is consistent with slower growth as a function of advancing gestational age.

We also examined the expression of cell cycle markers in CTBs within cell columns. Again, we analyzed sections of placental tissue from all trimesters of pregnancy. In first trimester specimens, immunolocalization of cell cycle markers defined two distinct zones within cell columns: a proliferative zone of cycling cells (proximal regions of cell columns) and a zone of differentiation where cells transit M phase and permanently withdraw from the cell cycle (distal regions of cell columns with the site of uterine attachment). In the proximal regions of cell columns, CTBs expressed markers of progression from G1 through M. Interestingly, most CTBs in close proximity to the basement membrane stained with anti-Mdm2 antibodies. In the distal regions of cell columns, the majority of CTBs expressed markers of the S, G2, and M phases of the cell cycle. CTBs in the uterine wall expressed only markers that correlate with progression from G2 through M. The number of cells in M phase progressively increased from the proximal to distal column region and reached a maximum in the superficial decidua. Again, results obtained by analyzing second and third trimester specimens pointed to a marked decrease in the mitotic potential of CTBs. In second trimester tissue, anchoring villi had shortened cell columns with reduced zones of proliferation. Most CTBs expressed markers of G2 through M phase. In third trimester tissue, column CTBs were greatly decreased in number and expressed the same markers as observed in first and second trimester tissue. Taken together, these results suggest that anchorage sites with CTBs in the cell cycle and completing M phase are present throughout gestation, although the total number of CTBs in this location at term is very low.

Unexpectedly, most of the nuclei in the syncytium in both first and second trimester tissue samples stained for cyclins A and B, but did not express their catalytic partner, Cdc2. At term, only a few syncytial nuclei, mostly in groups, stained for cyclins A and B. In addition, in second trimester tissue some STBs expressed the CDK inhibitors p16 and p57. Weak positive nuclear staining for p57 has been reported. 16 The meaning of these results is not clear, but is likely to be related to the fact that terminal differentiation along this pathway results in the novel process of fusion. Several reports show that terminally differentiated cells that are polyploid or multinuclear express an unusual repertoire of cell cycle regulators. For example, in bone marrow megakaryocytes undergoing endomitosis, cyclin B1 expression is sustained in the absence of CDK1. 65 Interestingly, endoreduplication, the differentiation pathway that gives rise to trophoblast giant cells in the mouse, is also characterized by the expression of an unusual set of cell cycle regulators. 66

In conclusion, our data show that the trophoblast populations at the maternal-fetal interface stain for a number of cell cycle regulators and that these staining patterns change as a function of both differentiation and gestational age. Currently, we are very interested in using the foregoing analysis of samples obtained during and after normal pregnancy to understand the etiology of pathological changes associated with pregnancy complications. Toward this end, we have determined that most of the staining patterns we observed were essentially unchanged in sections cut from placental tissues that were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formaldehyde (24 hours) and embedded in paraffin blocks. We are in the process of assaying archival tissues to determine which antigens survive under these conditions. Therefore, a subset of these cell cycle regulators have the potential to be clinically useful markers of trophoblast pathologies, analogous to the panel of markers, including Mdm-2, that are used as indicators of tumor progression. 67

Which pregnancy complications are most likely to be associated with alterations in trophoblast expression of cell cycle markers? In posing possible answers to this question, we have considered our findings that emphasize the importance of the rapid and highly regulated placental growth which precedes that of the embryo/fetus. The effects of physiological (eg, oxygen tension), pharmacological (eg, xenobiotics), and infectious (eg, cytomegalovirus) agents that impact transit through and exit from the cell cycle are likely to be greatest during the first and second trimesters. The magnitude of the effects is likely to be proportional to the assault, inducing abortion in the most severely affected pregnancies. We are also interested in whether pregnancy complications that are diagnosed in the late second and third trimesters show evidence of mitotic dysregulation. For example, both preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction are associated with abnormal cytotrophoblast invasion. We are currently investigating whether placental samples from these patients have altered expression of cell cycle markers. For example, a loss of Mdm2-positive vCTBs might be indicative of trophoblast damage, and an increase in the number of histone H3-positive cytotrophoblasts in columns might be evidence of compensatory repair.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rebecca Joslin and Ed Caceres for excellent technical assistance and Ms. Evangeline Leash for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Susan Fisher, HSW 604, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA 94143-0512. E-mail: sfisher@cgl.ucsf.edu.

Supported by a grant from the University of California Tobacco-Related Disease Program (3RT-0324) and HD 30367.

References

- 1.Damsky CH, Fisher SJ: Trophoblast pseudo-vasculogenesis: faking it with endothelial adhesion receptors. Curr Opin Cell Biol 1998, 10:660-666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cross JC, Werb Z, Fisher SJ: Implantation and the placenta: key pieces of the development puzzle. Science 1994, 266:1508-1518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rinkenberger JL, Cross JC, Werb Z: Molecular genetics of implantation in the mouse. Dev Genet 1997, 21:6-20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aplin JD, Haigh T, Lacey H, Chen CP, Jones CJ: Tissue interactions in the control of trophoblast invasion. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 2000, 55:57-64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher SJ, Damsky CH: Human cytotrophoblast invasion. Semin Cell Biol 1993, 4:183-188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guillemot F, Nagy A, Auerbach A, Rossant J, Joyner AL: Essential role of Mash-2 in extraembryonic development. Nature 1994, 371:333-336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Firulli AB, McFadden DG, Lin Q, Srivastava D, Olson EN: Heart and extra-embryonic mesodermal defects in mouse embryos lacking the bHLH transcription factor Hand1. Nat Genet 1998, 18:266-270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riley P, Anson-Cartwright L, Cross JC: The Hand1 bHLH transcription factor is essential for placentation and cardiac morphogenesis. Nat Genet 1998, 18:271-275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janatpour MJ, Utset MF, Cross JC, Rossant J, Dong J, Israel MA, Fisher SJ: A repertoire of differentially expressed transcription factors that offers insight into mechanisms of human cytotrophoblast differentiation. Dev Genet 1999, 25:146-157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anson-Cartwright L, Dawson K, Holmyard D, Fisher SJ, Lazzarini RA, Cross JC: The glial cells missing-1 gene is essential for branching morphogenesis in the chorioallantoic placenta. Nat Genet 2000, 25:311-314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damsky CH, Librach C, Lim KH, Fitzgerald ML, McMaster MT, Janatpour M, Zhou Y, Logan SK, Fisher SJ: Integrin switching regulates normal trophoblast invasion. Development 1994, 120:3657-3666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Librach CL, Werb Z, Fitzgerald ML, Chiu K, Corwin NM, Esteves RA, Grobelny D, Galardy R, Damsky CH, Fisher SJ: 92-kD type IV collagenase mediates invasion of human cytotrophoblasts. J Cell Biol 1991, 113:437-449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kovats S, Main EK, Librach C, Stubblebine M, Fisher SJ, DeMars R: A class I antigen, HLA-G, expressed in human trophoblasts. Science 1990, 248:220-223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMaster MT, Librach CL, Zhou Y, Lim KH, Janatpour MJ, DeMars R, Kovats S, Damsky C, Fisher SJ: Human placental HLA-G expression is restricted to differentiated cytotrophoblasts. J Immunol 1995, 154:3771-3778 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohn KW: Molecular interaction map of the mammalian cell cycle control and DNA repair systems. Mol Biol Cell 1999, 10:2703-2734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chilosi M, Piazzola E, Lestani M, Benedetti A, Guasparri I, Granchelli G, Aldovini D, Leonardi E, Pizzolo G, Doglioni C, Menestrina F, Mariuzzi GM: Differential expression of p57kip2, a maternally imprinted cdk inhibitor, in normal human placenta and gestational trophoblastic disease. Lab Invest 1998, 78:269-276 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ichikawa N, Zhai YL, Shiozawa T, Toki T, Noguchi H, Nikaido T, Fujii S: Immunohistochemical analysis of cell cycle regulatory gene products in normal trophoblast and placental site trophoblastic tumor. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1998, 17:235-240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bamberger A, Sudahl S, Bamberger CM, Schulte HM, Löning T: Expression patterns of the cell-cycle inhibitor p27 and the cell-cycle promoter cyclin E in the human placenta throughout gestation: implications for the control of proliferation. Placenta 1999, 20:401-406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tedde G, Tedde Piras A: Mitotic index of the Langhans’ cells in the normal human placenta from the early stages of pregnancy to the term. Acta Anatom 1978, 100:114-119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benirschke K, Kaufmann P: Pathology of the Human Placenta, 3rd ed. 1995, Springer-Verlag, New York

- 21.Fox H: Pathology of the Placenta, 1997, vol. 7. W. B. Saunders, 2nd ed. London

- 22.Bulmer JN, Morrison L, Johnson PM: Expression of the proliferation markers Ki67 and transferrin receptor by human trophoblast populations. J Reprod Immunol 1988, 14:291-302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnholdt H, Meisel F, Fandrey K, Löhrs U: Proliferation of villous trophoblast of the human placenta in normal and abnormal pregnancies. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol 1991, 60:365-372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mühlhauser J, Crescimanno C, Kaufmann P, Höfler H, Zaccheo D, Castellucci M: Differentiation and proliferation patterns in human trophoblast revealed by c-erbB-2 oncogene product and EGF-R. J Histochem Cytochem 1993, 41:165-173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Genbacev O, Zhou Y, Ludlow JW, Fisher SJ: Regulation of human placental development by oxygen tension. Science 1997, 277:1669-1672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Damsky CH, Fitzgerald ML, Fisher SJ: Distribution patterns of extracellular matrix components and adhesion receptors are intricately modulated during first trimester cytotrophoblast differentiation along the invasive pathway, in vivo. J Clin Invest 1992, 89:210-222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Y, Damsky CH, Chiu K, Roberts JM, Fisher SJ: Preeclampsia is associated with abnormal expression of adhesion molecules by invasive cytotrophoblasts. J Clin Invest 1993, 91:950-960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Genbacev O, Joslin R, Damsky CH, Polliotti BM, Fisher SJ: Hypoxia alters early gestation human cytotrophoblast differentiation/invasion in vitro and models the placental defects that occur in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest 1996, 97:540-550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou Y, Fisher SJ, Janatpour M, Genbacev O, Dejana E, Wheelock M, Damsky CH: Human cytotrophoblasts adopt a vascular phenotype as they differentiate: a strategy for successful endovascular invasion? J Clin Invest 1997, 99:2139-2151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sherr CJ: G1 phase progression: cycling on cue. Cell 1994, 79:551-555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weinberg RA: The retinoblastoma protein and cell cycle control. Cell 1995, 81:323-330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pines J: Protein kinases and cell cycle control. Semin Cell Biol 1994, 5:399-408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bartkova J, Lukas J, Strauss M, Bartek J: Cyclin D3: requirement for G1/S transition and high abundance in quiescent tissues suggest a dual role in proliferation and differentiation. Oncogene 1998, 17:1027-1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heichman KA, Roberts JM: Rules to replicate by. Cell 1994, 79:557-562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bartek J, Bartkova J, Lukas J: The retinoblastoma protein pathway and the restriction point. Curr Opin Cell Biol 1996, 8:805-814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Resnitzky D, Reed SI: Different roles for cyclins D1 and E in regulation of the G1-to-S transition. Mol Cell Biol 1995, 15:3463-3469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sherr CJ, Roberts JM: Inhibitors of mammalian G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Genes Dev 1995, 9:1149-1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiong Y, Hannon GJ, Zhang H, Casso D, Kobayashi R, Beach D: p21 is a universal inhibitor of cyclin kinases. Nature 1993, 366:701-704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Firpo EJ, Koff A, Solomon MJ, Roberts JM: Inactivation of a Cdk2 inhibitor during interleukin 2-induced proliferation of human T lymphocytes. Mol Cell Biol 1994, 14:4889-4901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan Y, Frisén J, Lee MH, Massagué J, Barbacid M: Ablation of the CDK inhibitor p57Kip2 results in increased apoptosis and delayed differentiation during mouse development. Genes Dev 1997, 11:973-983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parker SB, Eichele G, Zhang P, Rawls A, Sands AT, Bradley A, Olson EN, Harper JW, Elledge SJ: p53-independent expression of p21Cip1 in muscle and other terminally differentiating cells. Science 1995, 267:1024-1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nourse J, Firpo E, Flanagan WM, Coats S, Polyak K, Lee MH, Massague J, Crabtree GR, Roberts JM: Interleukin-2-mediated elimination of the p27Kip1 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor prevented by rapamycin. Nature 1994, 372:570-573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harper JW, Elledge SJ, Keyomarsi K, Dynlacht B, Tsai LH, Zhang P, Dobrowolski S, Bai C, Connell-Crowley L, Swindell E: Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases by p21. Mol Biol Cell 1995, 6:387-400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mantel C, Luo Z, Canfield J, Braun S, Deng C, Broxmeyer HE: Involvement of p21cip-1 and p27kip-1 in the molecular mechanisms of steel factor-induced proliferative synergy in vitro and of p21cip-1 in the maintenance of stem/progenitor cells in vivo. Blood 1996, 88:3710-3719 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dong F, Agrawal D, Bagui T, Pledger WJ: Cyclin D3-associated kinase activity is regulated by p27kip1 in BALB/c 3T3 cells. Mol Biol Cell 1998, 9:2081-2092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Y, Martindale JL, Gorospe M, Holbrook NJ: Regulation of p21WAF1/CIP1 expression through mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Cancer Res 1996, 56:31-35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Halevy O, Novitch BG, Spicer DB, Skapek SX, Rhee J, Hannon GJ, Beach D, Lassar AB: Correlation of terminal cell cycle arrest of skeletal muscle with induction of p21 by MyoD. Science 1995, 267:1018-1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee MH, Nikolic M, Baptista CA, Lai E, Tsai LH, Massagué J: The brain-specific activator p35 allows Cdk5 to escape inhibition by p27Kip1 in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996, 93:3259-3263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang H, Hannon GJ, Casso D, Beach D: p21 is a component of active cell cycle kinases. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 1994, 59:21-29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.LaBaer J, Garrett MD, Stevenson LF, Slingerland JM, Sandhu C, Chou HS, Fattaey A, Harlow E: New functional activities for the p21 family of CDK inhibitors. Genes Dev 1997, 11:847-862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clarke PR, Hoffmann I, Draetta G, Karsenti E: Dephosphorylation of cdc25-C by a type-2A protein phosphatase: specific regulation during the cell cycle in Xenopus egg extracts. Mol Biol Cell 1993, 4:397-411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gottlieb TM, Oren M: p53 in growth control and neoplasia. Biochim Biophys Acta 1996, 1287:77-102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.el-Deiry WS, Tokino T, Velculescu VE, Levy DB, Parsons R, Trent JM, Lin D, Mercer WE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B: WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell 1993, 75:817-825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen CY, Oliner JD, Zhan Q, Fornace AJ, Jr., Vogelstein B, Kastan MB: Interactions between p53 and MDM2 in a mammalian cell cycle checkpoint pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994, 91:2684-2688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen J, Wu X, Lin J, Levine AJ: mdm-2 inhibits the G1 arrest and apoptosis functions of the p53 tumor suppressor protein. Mol Cell Biol 1996, 16:2445-2452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwarting R: Little missed markers and Ki-67 (editorial). Lab Invest 1993, 68:597-599 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krude T, Jackman M, Pines J, Laskey RA: Cyclin/Cdk-dependent initiation of DNA replication in a human cell-free system. Cell 1997, 88:109-119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pines J, Hunter T: Human cyclins A and B1 are differentially located in the cell and undergo cell cycle-dependent nuclear transport. J Cell Biol 1991, 115:1-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ohi R, Gould KL: Regulating the onset of mitosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol 1999, 11:267-273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dunphy WG, Newport JW: Unraveling of mitotic control mechanisms. Cell 1988, 55:925-928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hendzel MJ, Wei Y, Mancini MA, Van Hooser A, Ranalli T, Brinkley BR, Bazett-Jones DP, Allis CD: Mitosis-specific phosphorylation of histone H3 initiates primarily within pericentromeric heterochromatin during G2 and spreads in an ordered fashion coincident with mitotic chromosome condensation. Chromosoma 1997, 106:348-360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haupt Y, Barak Y, Oren M: Cell type-specific inhibition of p53-mediated apoptosis by mdm2. EMBO J 1996, 15:1596-1606 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kubbutat MH, Jones SN, Vousden KH: Regulation of p53 stability by Mdm2. Nature 1997, 387:299-303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fiddler TA, Smith L, Tapscott SJ, Thayer MJ: Amplification of MDM2 inhibits MyoD-mediated myogenesis. Mol Cell Biol 1996, 16:5048-5057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Datta NS, Williams JL, Caldwell J, Curry AM, Ashcraft EK, Long MW: Novel alterations in CDK1/cyclin B1 kinase complex formation occur during the acquisition of a polyploid DNA content. Mol Biol Cell 1996, 7:209-223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.MacAuley A, Cross JC, Werb Z: Reprogramming the cell cycle for endoreduplication in rodent trophoblast cells. Mol Biol Cell 1998, 9:795-807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cuny M, Kramar A, Courjal F, Johannsdottir V, Iacopetta B, Fontaine H, Grenier J, Culine S, Theillet C: Relating genotype and phenotype in breast cancer: an analysis of the prognostic significance of amplification at eight different genes or loci and of p53 mutations. Cancer Res 2000, 60:1077-1083 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]