Abstract

Interfollicular small lymphocytic lymphoma (I-SLL) has not been well characterized and its relationship to small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) or chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is uncertain. Moreover, two different proliferation center growth patterns have been described with respect to reactive germinal centers. In this study, we evaluate the histological and immunophenotypic features of 13 cases of I-SLL and immunoglobulin heavy chain variable (VH) gene sequences from 10 cases. Immunophenotypic analyses indicate that cases showing either growth pattern have the same CD5-positive B cell phenotype typical of SLL or CLL. Sequence analysis revealed the use of VH, D, and J gene segments often found in CLL, although there may be more frequent use of J6. Similar to recent studies of CLL, there were approximately equal numbers of cases with either mutated or unmutated VH genes without evidence of ongoing mutation, consistent with I-SLL having either a naïve or memory B cell origin. Interestingly, the mutational status of the I-SLL VH genes seemed to correlate with the two different histological growth patterns. These studies support the proposal that I-SLL represents SLL/CLL and suggest the recently proposed two types of CLL originating from either memory or naïve B cells may have different histological patterns of growth in lymph nodes that show architectural preservation.

Small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) is a B cell neoplasm that closely resembles chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). It is widely recognized that SLL and CLL have the same immunophenotype (CD5+, CD23+, CD10−) and similar histological patterns of lymph node and marrow involvement. 1,2 The only recognized difference between CLL and SLL is the predominant site of disease with CLL being primarily bone marrow-based and SLL being primarily lymph node-based. 2 However, even this distinction is often arbitrary because both CLL and SLL show considerable overlap in terms of sites of involvement, especially in more advanced stages.

Interfollicular small lymphocytic lymphoma (I-SLL) as described by Ellison et al 3 is an indolent malignancy of small B lymphocytes present in the interfollicular areas of lymph nodes that histologically resembles SLL. Unlike typical SLL, however, the normal lymph node architecture is not completely effaced because reactive follicles and open sinuses are also present. Similar to SLL, I-SLL have proliferation centers that in some cases are present around the reactive follicles (perifollicular) and in others localized only between reactive follicles. Proliferation centers, which have also been termed pseudofollicles, are characteristic histological features of CLL or SLL and represent pale areas composed of cells that cytologically resemble prolymphocytes and paraimmunoblasts (intermediate-sized lymphocytes with central prominent nucleoli) and more mitotic figures. 4 Whether I-SLL does indeed represent SLL/CLL or some other type(s) of mature B cell neoplasm, however, has not been well established. Studies to confirm I-SLL cells have the characteristic immunophenotype of SLL have been reported for only a few cases. 5 Moreover, finding perifollicular proliferation centers is a histological pattern that suggests the possibility of a marginal zone B cell neoplasm that would not be expected to express CD5 or even an atypical mantle cell lymphoma. 1

The possibility that I-SLL may represent two distinct neoplasms, one with proliferation centers organized around reactive follicles and the other with proliferation centers found only between reactive follicles, is particularly interesting in light of recent studies of immunoglobulin VH genes that suggest CLL represents two distinct neoplasms. 6-9 Sequence analysis of VH genes can provide valuable information about the developmental stage of a lymphoma cell of origin, because somatic hypermutation is thought to occur as B cells pass through the germinal center. 10,11 Similar to their normal B cell counterparts, neoplasms of pregerminal center B cells seem to mostly express unmutated VH genes, neoplasms derived from postgerminal center B cells express mutated VH genes, whereas neoplasms of germinal center B cells typically show evidence of active hypermutation and have mutated VH genes. 11,12 Recent studies suggest that CLL can have either a pregerminal or postgerminal center cell of origin and that patients with these two different types of CLL have markedly different responses to treatment. 8,9 Whether these two proposed different types of CLL show histological differences in involved lymph nodes that still show significant architectural preservation is not known.

To further characterize I-SLL, 15 biopsies from 13 patients were analyzed in this study, and the VH genes were cloned and sequenced from 10 of the cases. These studies confirmed that I-SLL has an immunophenotype similar to SLL/CLL and are consistent with I-SLL representing SLL/CLL that shows preservation of lymph node architecture. They also suggest that the proposed two different types of pregerminal center or postgerminal center CLLs may have different histological patterns of growth.

Materials and Methods

Case Selection

The 13 cases studied were obtained from the hematopathology files of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. Selection was based on having histological features that resembled SLL on review of hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissue sections where there was also partial preservation of normal lymph node architecture with at least some intact sinuses and reactive follicles.

Immunohistochemical Staining

The various antibodies used and suppliers are listed in Table 1 ▶ . Staining was done on 5-μm deparaffinized tissue sections using the avidin-biotin complex technique of Hsu et al. 13 Various enhancement procedures were used including microwave treatment, protease treatment, or tyramide treatment (Dupont-New England Nuclear Research Products, Boston, MA). Hyperplastic human tonsil tissue sections were used as controls. The slides were also counterstained with hematoxylin before evaluation.

Table 1.

Antibodies Used for Immunohistochemistry

| Antibody (clone) | Source |

|---|---|

| CD20 (L26) | DAKO, Carpinteria, CA |

| CD3 | DAKO |

| CD43 (MT-1) | Biotest, Denville, NJ |

| CD43 (DF-T1) | DAKO |

| CD5 (4C7) | Novocastra/Vector, Burlingame, CA |

| CD23 (BU38) | Binding Site, Unlimited, Birmingham, UK |

| Cyclin D1 (5D4) | Immunotech, Westbrook, ME |

| Cyclin D1 (H295) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA |

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

DNA was isolated from unstained 5-μm tissue sections obtained from paraffin-embedded material as described. 14 All PCR reactions were performed in 50-μl volumes under standard conditions using Taq polymerase as described. 15 Initially, B cell clones were identified by amplifying a small proportion of the DNA preparation for 37 cycles with a 5′ consensus framework region 3 (FW3) and 3′ JH1 primer. The resultant products, which correspond mostly to CDR3 sequences, were subsequently electrophoresed in 8% acrylamide gels, stained with ethidium bromide, so that prominent bands indicative of monoclonal B cell populations could be easily identified. 14,15 The methods used for obtaining more complete length VH gene PCR products from paraffin-extracted DNA specimens have been previously described. 16 Briefly, DNA is first amplified for 37 cycles using a variety of 5′ primers specific for the framework region one (FW1) sequences of the various VH families with the consensus 3′ JH1 primer. To increase the sensitivity and obtain sufficient DNA for subsequent cloning, secondary amplification reactions were performed for 15 cycles using 0.5 μl of the initial reaction as template under the same conditions only substituting an internal JH primer (JH2 for JH1) or in two cases (case 1 and 13) an internal FW1 primer where it seemed the JH2 primer failed to work. Sequences for the various FW1 and JH primers used have been previously published. 16 The more full-length VH gene PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose and ethidium bromide staining.

Cloning and Sequencing of PCR Products

PCR products corresponding to the mostly complete VH genes were isolated from 1.5% low-melt agarose gels and the DNA purified using Wizard DNA preps (Promega, Madison, WI). Approximately one-third of the purified DNA was cloned using the PCR-Script kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Plasmid DNA used for sequencing reactions was obtained from overnight cultures of randomly selected bacterial colonies using Wizard minipreps (Promega). Dideoxy sequencing in both directions was performed using Sequenase (Amersham, Cleveland, OH) with approximately one-third of the DNA following the manufacture’s plasmid protocol. Isolation and purification of the clonal FW3-JH1 PCR products from 8% acrylamide gels was performed as described. 16 The small FW3-JH1 PCR products were directly sequenced from both ends as described. 16

Analysis of VH Sequences

Sequences were analyzed using version 4.0 MacVector software (IBI, New Haven, CT) and the VBASE database. 17 Germline D segments were assigned following the recommendations of Corbet et al 18 with the exception that one difference was allowed within a stretch of 10 consecutive nucleotides. Expected numbers of replacement (R) and silent (S) mutations in the CDRs and FWRs were calculated by considering all possible mutations as described by Chang and Casali. 19

Results

Clinical and Histological Findings

The 13 patients ranged in age from 39 to 78 years (median, 57 years) with six men and seven women (Table 2) ▶ . Although only limited clinical information was available, three of five patients studied were known to have widespread lymphadenopathy with at least three known sites of involvement above and below the diaphragm. The peripheral blood lymphocyte counts at diagnosis were reported to be normal in six of seven patients for whom this information was known and mildly elevated in one patient (12,800 per μl). Bone marrow involvement was documented in two of four patients examined. Six patients with follow-up information were alive with disease at 9 to 46 months.

Table 2.

Clinical Information

| Case no. | Age/sex | Widespread adenopathy | Lymphocyte count | Bone marrow | Disease status follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 58 /M | No | Normal | Indeterminate | AWD (37) |

| 2 | 53 /F | NA | Normal | NA | NA |

| 3 | 57 /F | Yes | Normal | Positive | AWD (28) |

| 4 | 50 /F | NA | NA | Negative | AWD (13) |

| 5 | 59 /M | Yes | Normal | NA | AWD (40) |

| 6 | 69 /F | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 7 | 55 /F | Yes | Normal | Positive | AWD (46) |

| 8 | 39 /M | NA | Elevated* | NA | NA |

| 9 | 78 /M | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 10 | 63 /M | No | NA | NA | NA |

| 11 | 57 /F | NA | Normal | NA | NA |

| 12 | 57 /M | NA | NA | NA | AWD (9) |

| 13 | 58 /F | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: F, female; M, male; AWD, alive with disease; NA, not available.

*The elevated peripheral blood lymphocyte count was 12,800 per μl.

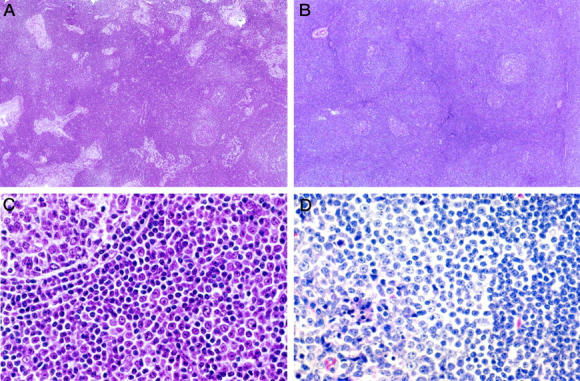

All 15 of the lymph node biopsies examined (nine cervical, six axillary) demonstrated at least partial architectural preservation. Nine cases had rare or focal subcapsular and intranodal sinuses, four cases showed moderate sinus preservation, and two cases had numerous intact sinuses (Table 3) ▶ . Reactive follicular centers, which varied in size, were present in all cases ranging from two to 66 follicles/low power (×2) field. Proliferation centers were present in all cases. In seven lymph node biopsies (cases 1 to 6), the proliferation centers were scattered between reactive follicles (Figure 1A) ▶ . The other eight lymph node biopsies (cases 7 to 13) demonstrated perifollicular proliferation centers sometimes also with scattered proliferation centers (Figure 1B) ▶ . The follicular centers associated with the perifollicular proliferation centers often had absent or thin mantle zones (Figure 1C) ▶ . Apparent localization of lymphoma cells in reactive follicles (follicular colonization) was seen in two cases with perifollicular proliferation centers (cases 7 and 13 and Figure 10). Two patients had two biopsies obtained at different times that showed proliferation centers with similar histological patterns (cases 1 and 7). A vaguely nodular growth pattern that by itself could raise the possibility of a follicular lymphoma was identified in six biopsies and was very pronounced in four cases, all with perifollicular proliferation centers.

Table 3.

Summary of Histologic Findings

| Case no. | Biopsy site* | Open sinuses | Reactive follicles (No./LPF) | Proliferation centers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cervical | 3+ | 38 | Scattered |

| Axillary | 1+ | 25 | Scattered | |

| 2 | Cervical | 1+ | 18 | Scattered |

| 3 | Cervical | 2+ | 7 | Scattered |

| 4 | Cervical | 1+ | 10 | Scattered |

| 5 | Axillary | 1+ | 6 | Scattered |

| 6 | Axillary | 2+ | 9 | Scattered |

| 7 | Axillary | 1+ | 11 | Scattered, perifollicular |

| Axillary | 1+ | 14 | Scattered, perifollicular | |

| 8 | Cervical | 2+ | 2 | Scattered, perifollicular |

| 9 | Axillary | 1+ | 66 | Perifollicular |

| 10 | Cervical | 1+ | 46 | Perifollicular |

| 11 | Cervical | 1+ | 25 | Perifollicular |

| 12 | Cervical | 2+ | 19 | Scattered, perifollicular |

| 13 | Cervical | 3+ | 15 | Perifollicular |

*All biopsies were lymph nodes. Two biopsies were available from case 1 and case 7 that were obtained 3 and 5 months apart, respectively. Numbers of open sinuses are estimated as being focal or rare (1+), moderate (2+), or numerous (3+). Numbers of reactive follicles are estimated from low-power field inspection (2×). Proliferation centers were seen growing around reactive follicles (perifollicular) or located between reactive follicles (scattered).

Figure 1.

Histological features of I-SLL. A: A low-power view of an I-SLL (case 4) that demonstrated extensive sinus preservation, reactive follicles, and only scattered pale proliferation centers. B: A low-power view of an I-SLL (case 9) with perifollicular proliferation centers around reactive follicles. C: A higher magnification of case 9 showing a reactive follicle (upper left) with its thin mantle zone surrounded by cells which closely resemble those of a proliferation center. D: A higher magnification of an I-SLL (case 13) that demonstrated reactive follicles partially colonized by proliferation center type I-SLL cells. The residual reactive follicular center cells are best seen in the lower left corner associated with tingible body macrophages.

Immunophenotypic Studies

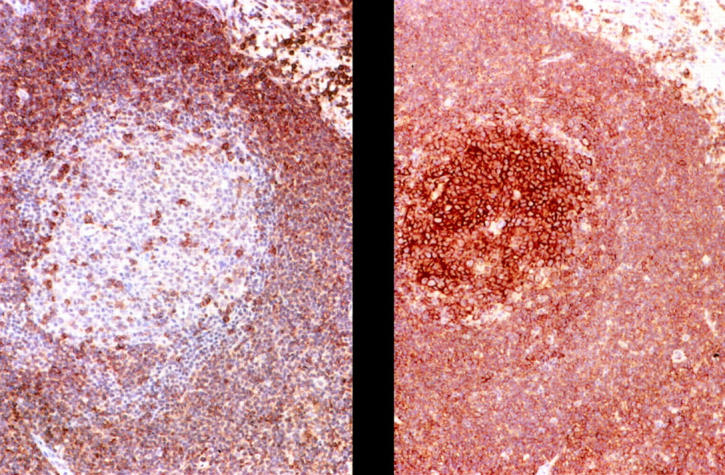

The neoplastic cells were L26 (CD20)-positive in all cases. Relative to the reactive follicles which demonstrated the strongest staining, the proliferation centers had intermediate CD20 intensity levels and the small lymphocytes, which made up the bulk of neoplastic population, were the most weakly stained (Figure 2) ▶ . The lymphoma cells in 10 of 13 cases were clearly CD5+-positive, and in three cases the staining was indeterminate (Table 4) ▶ . The three cases lacking definite CD5 positivity could only be studied by paraffin-section immunohistochemistry which has a lower sensitivity compared to flow cytometry of ∼80%. 20 The lymphoma cells were positive for CD43 in all 12 cases tested. Positive staining for CD23 was seen in 11 of 12 cases tested, whereas one case showed equivocal CD23 positivity. Staining for cyclin D1 was clearly negative in 12 of 13 cases tested and equivocal in one case. Surface immunoglobulin was weak to absent in the one case where staining intensity was known by flow cytometry (case 12).

Figure 2.

Representative immunohistochemical staining studies. Positive staining of I-SLL cells from case 1a with CD20 (right) and CD5 (left). Note the more intense CD20 staining of the follicular center cells relative to the more weakly staining I-SLL cells. Scattered CD5-positive T cells are present in the reactive follicle.

Table 4.

Results of Immunophenotypic Studies

| Case no. | CD5+ B cells* | CD43+ B cells† | CD23† | Cyclin D1† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | + (P, FZ) | + | + | − |

| 1b | + (P, FC) | + | + | − |

| 2 | + (P) | + | + | − |

| 3 | + (P) | + | + | − |

| 4 | + (FC), I (P) | + | + | I |

| 5 | + (P) | + | I | − |

| 6 | I (P) | + | + | − |

| 7a | + (P) | ND | ND | − |

| 7b | ND | + | + | ND |

| 8 | + (P) | + | + | − |

| 9 | I (P) | + | + | − |

| 10 | + (P) | + | + | − |

| 11 | I (P) | + | + | − |

| 12 | + (FC) | ND | ND | ND |

| 13 | + (P) | + | + | − |

*ND, not done; I, indeterminate; P, paraffin sections; FZ, frozen sections; FC, flow cytometry. Areas composed almost entirely of B cells were identified by CD20 staining.

†These studies were performed only on paraffin sections.

VH Gene Analysis

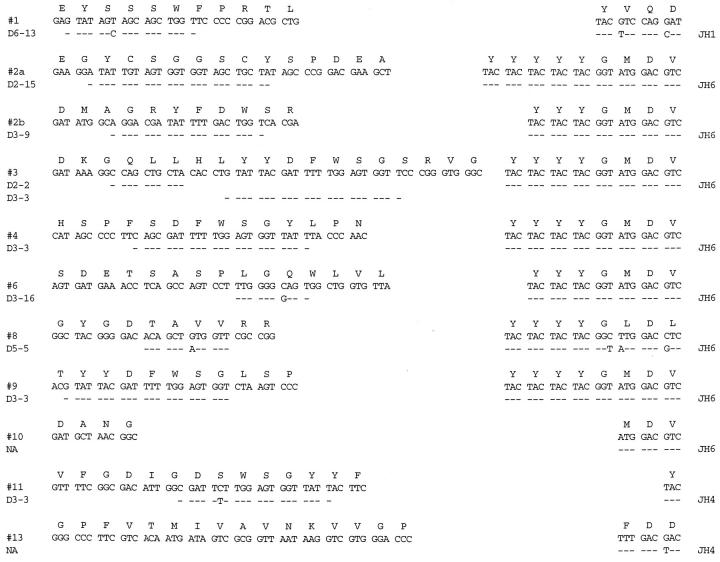

Rearranged VH genes were amplified, cloned, and sequenced from the 10 cases where DNA could be obtained. Clonally related repetitive VH sequences that had identical CDR3s were identified in all 10 cases (Figure 3 ▶ , Table 5 ▶ ). The same CDR3 sequences were also independently obtained by directly sequencing the clonal bands identified in each case using a standard heavy-chain PCR technique. This was done to confirm that the repetitively isolated VH sequences indeed represented B cell clones and were not repetition artifacts that can potentially arise with very poor quality DNA that is sometimes obtained from paraffin-embedded tissue specimens. All of the VH genes seemed to be functional because no stop codons or frame shifts were identified. In one case (case 2) two apparently functional VH genes were obtained which could represent the lack of allelic exclusion that has been described in occasional cases of CLL. 21 Comparing these clonal I-SLL VH genes to the known germline gene segments revealed that six of 11 used VH gene segments from the VH3 family, four from the VH1 family, and one from the VH4 family. Although most of the identified germline VH gene segments were found in only one clone, the V1-69 and V3-9 gene segments were both used by two different VH genes. Germline D segments could be assigned to all but two of the 11 VH genes (Figure 3) ▶ . As summarized in Table 5 ▶ , D segments from the D3 family were used most often being found in six of 11 (55%) VH genes. The D3-3 gene segment was the most frequently used member of the D3 family being found in four of 11 (36%) of cases and always in the same hydrophobic reading frame. The J6 gene segment was used by eight of 11 VH genes which may account for the average CDR3 length of 18.7 being slightly longer than normal (Figure 3) ▶ . Inspection of the deduced CDR3 amino acid sequence did not reveal conserved motifs between the VD or DJ junctions (Figure 3) ▶ .

Figure 3.

CDR3 sequences of I-SLL VH genes. The deduced amino acid sequences are shown along with the proposed D and J segment assignments. Nucleotide identity from the proposed D and J sequences is indicated with a dash. NA indicates that D segments could not be assigned with the described criteria. The complete VH gene nucleotide sequences have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession numbers AF299096-AF299106).

Table 5.

Analysis of I-SLL VH Sequences

| Case no. | VH gene (family) | % Homology (no. mutations) | J gene | D gene | Related seq/total seq |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | V3-48 (VH3) | 97.2 (7) | J1 | D6-13 | 3 /3 |

| 2 (band 1)* | V1-2 (VH1) | 100 (0) | J6 | D2-15 | 4 /4 |

| 2 (band 2)* | V3-9 (VH3) | 99.6 (1) | J6 | D3-9 | 2 /8 |

| 3 | V3-9 (VH3) | 99.6 (1) | J6 | D3-3 & D2-2 | 5 /5 |

| 4 | V1-69 (VH1) | 99.0 (3) | J6 | D3-3 | 3 /3 |

| 6 | V1-18 (VH1) | 99.3 (3) | J6 | D3-16 | 3 /3 |

| 8 | V4-34 (VH4) | 91.6 (21) | J6 | D5-5 | 4 /4 |

| 9 | V3-30 (VH3) | 100 (0) | J6 | D3-3 | 3 /3 |

| 10 | V3-21 (VH3) | 99.0 (3) | J6 | NA | 3 /3 |

| 11 | V1-69 (VH1) | 95.2 (14) | J4 | D3-3 | 2 /2 |

| 13 | V3-23 (VH3) | 94.8 (13) | J4 | NA | 3 /3 |

*Case 2 had two clonal bands both of which appeared to represent functional rearrangements. The germline V3-21 VH gene segment for case 11 is the HHG4 variant. Homology values for mutated VH genes (homology 98% or less) are in bold.

Mutational Analysis

Four of the VH sequences (cases 1, 8, 11, and13) showed significant numbers of apparent point mutations from the proposed germline gene sequences that cannot easily be explained by germline polymorphisms or Taq polymerase errors. All of these four mutated VH gene segments had homology values of 97% or less to the proposed germline genes (Table 5) ▶ , whereas the seven VH gene segments considered to be unmutated all had homology values of 99% or more. Information concerning the types of mutations, either replacement or silent, and locations in the VH gene segments, either CDR or FWR, is summarized in Table 6 ▶ for the four mutated VH genes. Two of these VH gene segments seem to have more replacement than silent mutations in CDR1 and CDR2 than would be expected by chance alone (cases 11 and 13). This finding suggests that at least some of the replacement mutations in the CDRs may have been positively selected through antigen binding.

Table 6.

Analysis of Mutations in Mutated I-SLL VH Genes

| Case no. | CDR1 and 2 | FW1,2, and 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R* | S | R/S | Random R/S | R | S | R/S | Random R/S | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4.4 | 2 | 4 | .5 | 2.8 |

| 8 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4.5 | 9 | 8 | 1.1 | 2.7 |

| 11 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 3.6 | 5 | 3 | 1.7 | 3.0 |

| 13 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 3.5 | 5 | 2 | 2.5 | 2.9 |

*Listed mutations were present in all VH clones from a given case and classified as replacement (R) or silent (S). Random R/S ratios represent the values expected by considering all possible mutations as described by Chang and Casali. 19

In addition to mutations from germline present in all of the VH clones from four of these cases, occasional isolated nucleotide differences were also identified between the different VH clones analyzed in eight of the cases. However, the frequencies of these differences were not significantly different from the Taq polymerase error rate which was estimated to be ∼0.2% from sequencing multiple VH clones from a mantle cell lymphoma case.

Discussion

Ellison et al 3 proposed that I-SLL represented an indolent primarily lymph node-based neoplasm of interfollicular B cells that could display two histological growth patterns. All cases had proliferation centers but in approximately half of the described cases, the proliferation centers surrounded reactive germinal centers, whereas in the other cases, the proliferation centers were present only between reactive follicles. It was also suggested based on morphological analysis that I-SLL represented early or in situ SLL.

To further study whether I-SLL represents a single entity and how it may be related to SLL/CLL, 15 biopsies from 13 different cases were obtained from our tissue archives. The cases selected for study were histologically and clinically similar to those described by Ellison. 3 They were approximately equally divided between those that had proliferation centers located around reactive follicles (perifollicular) and those where the proliferation centers were present only between reactive follicles. The majority of lymphoma cells in the proliferation centers, even when perifollicular, were cytologically indistinguishable from the prolymphocytes and paraimmunoblasts present in SLL/CLL. In two cases with perifollicular proliferation centers, the prolymphocyte-like cells were present within reactive follicles, so called “follicular colonization.” Although this histological feature had not been previously described for I-SLL, it does not help elucidate the cellular origin because follicular colonization has been described in postgerminal center marginal zone B cell lymphomas 22 as well as pregerminal center mantle cell lymphomas. 23

Immunophenotypic studies indicate that I-SLL with either pattern of growth is a B cell neoplasm that resembles SLL/CLL in being positive for CD5, CD23, and CD43. 1 Although mantle cell lymphomas also typically express CD5, the observed cyclin D1 negativity effectively rules this out from consideration and the positive staining with CD23 would also be very unusual for mantle cell lymphoma. 1 In addition, cases with perifollicular proliferation centers also differed cytologically from typical mantle cell lymphomas where prolymphocytes and paraimmunoblasts are not usually found. 1 The presence of proliferation centers surrounding reactive germinal centers with absent or thinned mantle zones gives these I-SLL lymphomas an appearance that can resemble marginal zone lymphomas. 1,5 However, I-SLL differs immunophenotypically from marginal zone lymphomas that are only rarely CD5- or CD23-positive. 1 In addition, the malignant monocytoid appearing perifollicular cells in marginal zone lymphomas also usually differ cytologically from the prolymphocytes and paraimmunoblasts present in I-SLL.

The use of specific VH gene segments that we observed further supports I-SLL being closely related to SLL/CLL. For example, seven of the nine different I-SLL VH gene segments we identified have been reported to be frequently used by CLL being found in ∼5% or more of cases. 6,8 Two I-SLL cases used the V1-69 gene segment that seems to be overrepresented in CLL relative to normal CD5-positive B cells being found in |mf10 to 20% of cases. 6,8,24 The V4-34 gene segment, which also seems to be overrepresented in CLL relative to normal CD5-positive B cells 6,8 was identified in one I-SLL case. The frequent use of D3-3 (formally called DXP4) which was present in four of 11 VH genes (36%) is similar to what has been described for CLL 6,8 and may be related to the high frequency this D segment is used by normal CD5-positive B cells. 25 Additional I-SLL cases will need to be examined to determine whether the use of J6 which was identified in eight of 11 genes (76%) is significantly different from that observed in CLL or normal CD5-positive B cells.

Similar to what has been described for CLL, the VH genes used by I-SLL are either mutated (homology 98% or less from germline) or nonmutated (homology 99% or greater) and do not show evidence of ongoing mutation. 6,8 Because VH gene hypermutation is thought to occur as B cells pass through the germinal center, these findings are consistent with I-SLL, like CLL/SLL, representing two malignancies, one derived from naïve unmutated pregerminal center B cells and one of mutated postgerminal center memory B cells. 8,9 It may be significant that two of the four mutated I-SLL VH genes identified in this study use the V4-34 and V3-23 gene segments which seem to be almost always mutated when found in CLL. 6,8 In addition, all seven of the nonmutated I-SLL VH genes used the J6 joining segment, which may be related to J6 being overrepresented by |mf10-fold in nonmutated relative to mutated productive VH rearrangements in normal CD5-positive B cells. 26 These findings further support the possibility that I-SLL with mutated and unmutated VH genes represents two distinct malignancies and also suggest they may recognize different antigens.

An especially interesting finding of this study is that the VH gene mutation status seems to correlate with the two different patterns of proliferation center growth seen in I-SLL. Specifically, three of the five sequenced I-SLL with perifollicular proliferation centers had highly mutated VH genes, whereas five of six VH genes from I-SLL with proliferation centers located only between reactive follicles were unmutated. Although the correlation was not perfect, the mutated VH gene from the single case where perifollicular proliferation centers were not identified (case 1) had approximately half as many mutations as the three other mutated cases suggesting it may be different from the others. Also, reexamination of the histology of this case after unmasking the VH gene mutation status revealed several follicles that may have been associated with subtle perifollicular proliferation centers. Conversely, the VH gene in one of the two cases with perifollicular proliferation centers that was classified as nonmutated (case 10) had three mutations and was most homologous to a germline gene termed HHG4. 27 However, HHG4, which is thought to be a variant of V3-21 differing at three nucleotide positions, has yet to be identified in a genomic clone. 17 It is possible, therefore, that the VH gene from case 10 may have additional mutations where V3-21 and HHG4 differ which would place it in the mutated category (<99% homologous). Although most memory B cells have mutated VH genes, it is also possible that the two cases with perifollicular proliferations centers without mutated VH genes display other markers of memory B cells such as CD148. 28

Because most lymph node biopsies of CLL/SLL show complete architectural effacement, our data are consistent with I-SLL representing early CLL/SLL as initially suggested by Ellison. 3 Indeed, one the two follow-up biopsies analyzed in this study showed greater effacement and less of an interfollicular growth pattern than the initial biopsy obtained several months earlier in agreement with this sequence of events (case 1). After complete architectural effacement, it is unlikely that cases with perifollicular proliferation centers will be histologically distinguishable from those with only scattered proliferation centers although they may appear more vaguely nodular. Therefore, only lymph node biopsies where there is less architectural effacement may be predictive of the VH mutational status.

In summary, the immunophenotypic and VH gene findings from this study support I-SLL being closely related, if not identical, to CLL/SLL. It is still possible, however, there are some biological differences between I-SLL and typical SLL/CLL that remain to be identified. From a diagnostic standpoint, I-SLL is important to recognize because it can be confused histologically with reactive follicular hyperplasia, marginal zone lymphoma, or occasionally follicular lymphoma. The clinical features of our patients and those described by Ellison 3 support I-SLL being primarily a nodal-based disease, although bone marrow involvement may be a frequent finding. In addition, the frequency of subtle peripheral blood involvement in I-SLL is not settled because immunophenotypic or genotypic studies would be required to document involvement in the absence of a lymphocytosis, although it seems peripheral blood involvement does sometimes occur. 5 Our studies also suggest that I-SLL represents two distinct neoplasms, one derived from naive pregerminal center B cells and one from postgerminal center memory B cells, with the later being more often associated with the presence of perifollicular proliferation centers. The recent studies of CLL relating VH mutation status with survival 8,9 suggest that I-SLL cases with perifollicular proliferation centers may have a better prognosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank John Miklos for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to David W. Bahler, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Pathology, University of Utah School of Medicine, Room 5C124, Salt Lake City, UT 84132. E-mail: bahlerdw@aruplab.com.

Supported by the Pathology Education and Research Foundation (University of Pittsburgh) and a Translational Research Grant from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (D. W. B.).

References

- 1.Swerdlow SH: Small B-cell lymphomas of the lymph nodes and spleen: practical insights to diagnosis and pathogenesis. Mod Pathol 1998, 12:125-140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein H, Banks PM, Chan JKC, Cleary ML, Delsol G, De Wolf-Peeters C, Falini B, Gatter KC, Grogan TM, Isaacson PG, Knowles DM, Mason DY, Muller-Hermelink H, Pileri SA, Piris MA, Ralfkiaer E, Warnke RA: A revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the international lymphoma study group. Blood 1994, 84:1361-1392 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellison DG, Nathwani BN, Cho SY, Martin SE: Interfollicular small lymphocytic lymphoma: the diagnostic significance of pseudofollicles. Hum Pathol 1989, 20:1108-1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmid C, Isaacson PG: Proliferation centers in B-cell malignant lymphoma, lymphocytic (B-CLL): an immunophenotypic study. Histopathology 1994, 24:445-451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen DT, Diamond LW, Schwonzen M, Bohlen H, Diehl V: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia with an interfollicular architecture: avoiding diagnostic confusion with monocytoid B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 1995, 18:179-184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fais F, Ghiotto F, Hashimoto S, Sellars B, Valetto A, Allen SL, Schulman P, Vinciguerra VP, Rai K, Rassenti LZ, Kapps TJ, Dighiero G, Schroeder HWJ, Ferrarini M, Chiorazzi N: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells express restricted sets of mutated and unmutated antigen receptors. J Clin Invest 1998, 102:1515-1525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oscier DG, Thompsett A, Shu D, Stevenson FK: Differential rates of somatic hypermutation in VH genes among subsets of chronic lymphocytic leukemia defined by chromosomal abnormalities. Blood 1997, 89:4153-4160 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamblin TJ, Davis Z, Gardiner A, Oscier DG, Stevenson FK: Unmutated Ig VH genes are associated with a more aggressive form of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 1999, 94:1848-1854 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damle RN, Wasil T, Fais F, Ghiotto F, Valetto A, Allen SL, Buchbinder A, Budman D, Dittmar K, Kolitz J, Lichtman SM, Schulman P, Vincigurerra VP, Rai KR, Ferrarini M, Chiorazzi N: Ig V gene mutation status and CD38 expression as novel prognostic indicators in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 1999, 94:1840-1847 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pascual V, Liu Y-J, Magalski A, de Bouteiller O, Banchereau J, Capra JD: Analysis of somatic mutation in five B cell subsets of human tonsil. J Exp Med 1994, 180:329-339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein U, Goossens T, Fischer M, Kanzler H, Braeuninger A, Rajewsky K, Kuppers R: Somatic hypermutation in normal and transformed human B cells. Immunol Rev 1998, 162:261-280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevenson F, Sahota S, Zhu D, Ottensmeier C, Chapman C, Oscier D, Hamblin T: Insight into the origin and clonal history of B-cell tumors as revealed by analysis of immunoglobulin variable region genes. Immunol Rev 1998, 162:247-259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu SM, Raine L, Fanger H: The use of avidin-biotin peroxidase complex (ADC) and unlabeled antibody (PAP) procedures. J Histochem Cytochem 1981, 29:557-580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lister J, Miklos JA, Swerdlow SH, Bahler DW: A clonally distinct recurrence of Burkitt’s lymphoma at 15 years. Blood 1996, 88:1407-1410 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bahler DW, Miklos JA, Swerdlow SH: Ongoing Ig gene hypermutation in salivary gland mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue-type lymphomas. Blood 1997, 89:3335-3344 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bahler DW, Swerdlow SH: Clonal salivary gland infiltrates associated with myoepithelial sialadenitis (Sjogren’s syndrome) begin as nonmalignant antigen-selected expansions. Blood 1998, 91:1864-1872 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook GP, Tomlinson IM: The human immunoglobulin VH repertoire. Immunol Today 1995, 16:237-242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corbet SJ, Tomlinson IM, Sonnhammer EL, Buck D, Winter G: Sequence of the human immunoglobulin diversity (D) segment locus: a systematic analysis provides no evidence for the use of DIR segments, inverted D segments, “minor” D segments, or D-D recombination. J Mol Biol 1997, 270:587-597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang B, Casali P: The CDR1 sequences of a major proportion of human germline Ig VH genes are inherently susceptible to amino acid replacement. Immunol Today 1994, 15:367-373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen CC, Raikow RB, Sonmez-Alpan E, Swerdlow SH: Classification of small B-cell lymphoid neoplasms using a paraffin section immunohistochemical panel. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2000, 8:1-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rassenti LZ, Kipps TJ: Lack of allelic exclusion in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Exp Med 1997, 185:1435-1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isaacson PG, Wotherspoon AC, Pan L: Follicular colonization in B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Am J Surg Pathol 1991, 15:819-828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swerdlow SH, Zukerberg LR, Yang WI, Harris NL, Williams ME: The morphologic spectrum of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas with BCL1/cyclin D1 gene rearrangements. Am J Surg Pathol 1996, 20:627-640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson TA, Rassenti LZ, Kipps TJ: Ig VH 1 genes expressed in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia exhibit distinctive molecular features. J Immunol 1997, 158:235-246 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berzinschek HP, Berzinschek RI, Lipsky PE: Analysis of the heavy chain repertoire of human peripheral B cells using single-cell polymerase chain reaction. J Immunol 1995, 155:190-202 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brezinschek HP, Foster SJ, Brezinschek RI, Dorner T, Domiati-Saad R, Lipsky PE: Analysis of human VH gene repertoire: differential effects of selection and somatic hypermutation on human peripheral CD5+/IgM+ and CD5−/IgM+ B cells. J Clin Invest 1997, 99:2488-2501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuppers R, Fischer U, Rajewsky K, Fause A: Immunoglobulin heavy and light chain gene sequences of a human CD5 positive immunocytoma and sequences of four novel VHIII germline genes. Immunol Lett 1992, 34:57-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tangye SG, Liu YJ, Aversa G, Phillips JH, deVries JE: Identification of functional human splenic memory B cells by expression of CD148 and CD27. J Exp Med 1998, 188:1691-1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]