Abstract

To investigate the physiological function of the cellular isoform of prion protein (PrPC), the gene expression profile was studied by analyzing a cDNA expression array containing 597 clones of various functional classes in two distinct skin fibroblast cell lines designated SFK and SFH, established from PrP-deficient (PrP−/−) mice and PrP+/+ mice, respectively. The cells were incubated in the culture medium with or without inclusion of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF). When SFK cells were compared with SFH cells in untreated conditions, the expression of 15 genes, including those essential for cell proliferation and adhesion, was reduced, whereas the expression of 27 genes, including those involved in the insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) signaling pathway, was elevated. Northern blot analysis verified a significant down-regulation of the receptor tyrosine kinase substrate Eps8, cyclin D1, and CD44 mRNAs, and a substantial up-regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase p85, IGF-I, and serine protease inhibitor-2.2 mRNAs in SFK cells. The patterns of induction or reduction of gene expression after exposure to bFGF showed considerable overlap between both cell types. Furthermore, both Eps8 and CD44 mRNA levels were reduced greatly in the brain tissues of the cerebrum isolated from the PrP−/− mice. These results indicate that the disruption of the PrP gene resulted in an aberrant regulation of a battery of genes important for cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival, including those located in the Ras and Rac signaling pathways.

Prion diseases are a group of neurodegenerative disorders affecting both animals and humans. 1 The majority of these diseases are transmissible and characterized by intracerebral accumulation of an abnormal prion protein (PrPSc) that is identical in the amino acid sequence to the cellular isoform (PrPC) expressed on the cell surface and attached by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor. The PrPSc protein differs biochemically from PrPC by its β-sheet-enriched structure, detergent insolubility, limited proteolysis by proteinase K, and slower turnover rate. 1 It has been proposed that the conversion of PrPC into PrPSc is mediated by a homotypic interaction between endogenous PrPC and incoming or de novo generated PrPSc via an undefined post-translational process. 1 The gene coding for the PrPC protein is expressed constitutively in a wide variety of neural and nonneural tissues at the highest level in neurons in the central nervous system (CNS), yet little is known about its biological functions. 2,3 Recent studies indicate that the phylogenetically conserved octarepeat region of the PrPC protein has a capacity to bind copper, suggesting that PrPC plays a role in copper metabolism. 4,5

Recently, five independent groups have established lines of mice devoid of the PrPC protein (PrP−/−), designated Zur, Npu, Ngsk, Rcm0, and Rikn, using different gene-targeting strategies. 6-13 The entire open reading frame of the PrP gene (Prnp) was replaced by selectable markers in Ngsk, Rcm0, and Rikn PrP−/− mice, whereas a part of the open reading frame remained intact in Zur and Npu PrP−/− mice. All of these mice exhibited normal early development and complete protection against scrapie infection, indicating that PrPC, a dispensable protein in embryonic development, is essential for inducing prion diseases. 6-12 Zur PrP−/− mice showed impairment in the GABAA receptor-mediated fast inhibition and long-term potentiation in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons, suggesting that PrPC is necessary for normal synaptic function and plasticity in the hippocampus. 14,15 However, some investigators were unable to confirm these observations. 16 Both Zur and Npu PrP−/− mice exhibited altered circadian activity rhythms and sleep patterns. 17 Ngsk, Rcm0, and Rikn PrP−/− mice exhibited late-onset cerebellar ataxia due to an extensive loss of Purkinje cells in the cerebellum. 10-12 Furthermore, Ngsk PrP−/− mice showed a significant amount of demyelination in the spinal cord and peripheral nerves, although the pathophysiological basis for these abnormalities remains unclear. 10-12 The introduction of a wild-type PrP transgene rescued them from Purkinje cell degeneration and demyelination, indicating that PrPC is directly involved not only in the long-term survival of Purkinje neurons but also in the myelinating capacity of oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells. 10,11

The cDNA array technology is a novel approach that allows monitoring of the expression pattern of a large number of genes systematically in a single hybridization, using cDNA probes prepared from different RNA sources on a matrix where a wide variety of cDNA fragments or oligonucleotides are arrayed and immobilized. 18,19 Previously, using Western blot analysis, we showed that the constitutive and heat-inducible expression of heat shock proteins, HSP105, HSP72, HSC70, HSP60, and HSP25 was similar between two distinct fibroblast cell lines isolated from Ngsk PrP−/− mice and the control PrP+/+ mice, suggesting that the PrPC protein may not act as a cellular regulator during a heat shock response. 20 In this study, the gene expression profile was studied in these cell lines by analyzing a cDNA expression array containing 597 clones of various functional classes to elucidate the physiological function of the PrPC protein.

Materials and Methods

Skin Fibroblast Cell Lines Established from Ngsk Prion Protein-Deficient Mice and Control Mice

The method for producing mice homozygous for a disrupted PrP gene (Ngsk PrP−/− mice) was previously described. 9-11 Three distinct fibroblast cell lines were established from abdominal skin explant cultures of the homozygous PrP−/− mice with a mixed 129/Sv × C57BL/6J background (SFK), the heterozygous PrP+/− mice (SFHT), and the control C57BL/6J PrP+/+ mice (SFH) at ages 35 to 50 weeks, as described previously. 20 Both PrP−/− and PrP+/− mice were produced by intercross between F1 PrP+/− breeding pairs and their genotypes were determined by Southern blot analysis, 9-11 whereas PrP+/+ mice were obtained from Kyudo (Kumamoto, Japan). The cells were plated in 25-cm 2 culture flasks at a density of 10 6 cells/flask and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2/95% air incubator in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin (feeding medium). The passage of the cultures was performed biweekly. They were maintained for 4 months (SFK, SFH, and SFHT) or 7 months (SFK) before starting the experiments. After the cultures became subconfluent, the culture medium was replaced by a feeding medium containing 1% FBS instead of 10% FBS; this is the low serum concentration (LS) medium. After a 72-hour incubation in LS medium with or without inclusion of 50 ng/ml of recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for the final 24 hours, they were processed for RNA preparation.

Extraction of RNA and Synthesis of 32P-Labeled cDNA Probes

Total RNA was extracted from bFGF-treated SFK, SFH, and SFHT cells (SFK-B, SFH-B, and SFHT-B) and untreated SFK, SFH, and SFHT cells (SFK-C, SFH-C, and SFHT-C), or from the whole cerebral cortices isolated from the PrP−/− mice (CBRK) and from the PrP+/+ mice (CBRH), from which SFK or SFH cells have originated. Poly A+ RNA was purified from total RNA pretreated with DNase I, using the oligotex-dT30 latex bead system (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). One microgram of poly A+ RNA was reverse-transcribed by incubating at 50°C for 20 minutes in 11 μl of a reaction mixture containing 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 75 mmol/L KCl, 3 mmol/L MgCl2, 500 μmol/L dCTP, 500 μmol/L dGTP, 500 μmol/L dTTP, 5 μmol/L dATP, 35 μCi of [α-32P]dATP, 5 mmol/L DTT, 50 units of Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcriptase, and the coding sequence primers at a final concentration of 1× using a commercial kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) followed by purification through column chromatography.

Southern Blot Hybridization of a cDNA Expression Array

A set of filters containing 597 mouse cDNA clones of various functional classes immobilized as a spot of duplicate dots on a positively charged nylon membrane (Atlas Mouse cDNA Expression Array I, Clontech) were hybridized at 68°C overnight in the hybridization solution containing the 32P-labeled cDNA probes at a concentration of 1 × 10 6 cpm/ml, according to the methods described previously. 21 The membranes were exposed to Kodak BioMax MS X-ray films with the intensifying screen at −80°C for 24 hours. For rehybridization, the probes were stripped from the membranes by washing in boiled 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate solution for 15 minutes. Densitometric analysis was performed on an imaging system using NIH Image version 1.61 software. The signal intensities were standardized against those of a housekeeping gene, β-actin.

RT-PCR Analysis and Northern Blot Analysis

For reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis, 5 μg of total RNA pretreated with DNase I was processed for cDNA synthesis using oligo(dT)12–18 primers and SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD). Fifty nanograms of cDNA were amplified by PCR using the specific sense and antisense primers listed in Table 1 ▶ . For Northern blot analysis, 2 μg (SFK, SFH, and SFHT) or 6 μg (CBRK and CBRH) of total RNA was separated on a 1.5% agarose-6% formaldehyde gel, transferred onto nylon membranes, and immobilized by UV fixation as described previously. 21,22 The membranes were hybridized at 53°C overnight in the hybridization buffer containing a digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled DNA probe synthesized using a PCR DIG probe synthesis kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) and the specific sense and antisense primers listed in Table 1 ▶ . The membranes were further processed for rehybridization with the DIG-labeled DNA probe specific for the β-actin gene to normalize the reaction. The specific reaction was visualized using the DIG chemiluminescence detection kit (Boehringer Mannheim).

Table 1.

Primer Sequences Used for PCR Amplification

| Primers | Sequence | Product size (bp) | Genbank accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eps8 sense | 5′TGTCTAACCGCTCCAGTGGGTATG3′ | 676 | L21671 |

| Eps8 antisense | 5′CTAACGTCCACCTGTGTGACAGTC3′ | ||

| cyclin D1 sense | 5′CGTACCCTGACACCAATCTCCTCA3′ | 641 | S78355 |

| cyclin D1 antisense | 5′TGTGCGGTAGCAGGAGAGGAAGTT3′ | ||

| CD44 sense | 5′AATGTAACCTGCCGCTACGCAGGT3′ | 475 | M27129 |

| CD44 antisense | 5′AGCCGCTGCTGACATCGTCATCTA3′ | ||

| PI3K p85 sense | 5′AGTGCAGAGGGCTACCAGTACAGA3′ | 484 | M60651 |

| PI3K p85 antisense | 5′GTCGTAATTCTGCAGGGTTGCTGG3′ | ||

| IGF-I sense | 5′TCGTCTTCACACCTCTTCTACCTG3′ | 369/421 | X04480 |

| IGF-I antisense | 5′GGTCTTGTTTCCTGCACTTCCTCT3′ | ||

| Spi-2.2 sense | 5′GAACTCCCCAAGTGTTGACGCTTC3′ | 521 | M64086 |

| Spi-2.2 antisense | 5′GTGGACAAAGTGAGGAGATCCTGC3′ | ||

| PrP sense | 5′CATTTTGGCAACGACTGGGAGGAC3′ | 551 | M13685 |

| PrP antisense | 5′GACTCCATCAAAGGGACCTGAAGC3′ | ||

| β-actin sense | 5′GAGCACAGCTTCTTTGCAGCTCCT3′ | 255 | X03672 |

| β-actin antisense | 5′GGTCAGGATACCTCTCTTGCTCTG3′ |

PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; IGF-I, insulin-like growth factor-I; Spi, serine protease inhibitor; PrP, prion protein.

Results

Nonexpression of the PrP Gene in SFK Cells Derived from the PrP−/− Mice

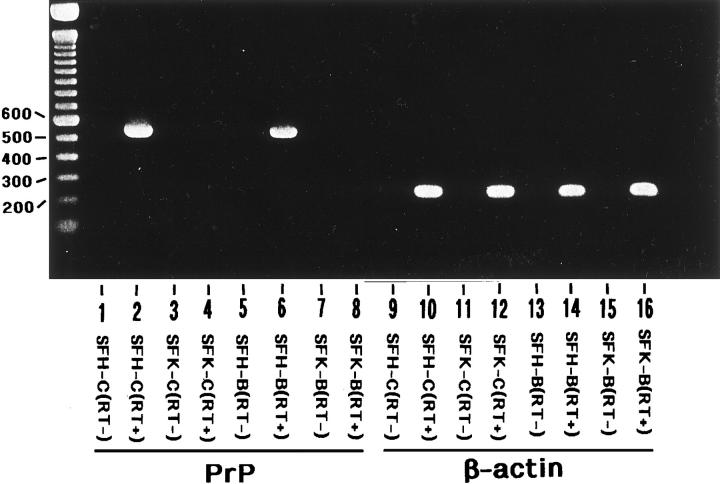

With RT-PCR analysis, the expression of PrP mRNA was undetectable in bFGF-treated and untreated SFK cells (SFK-B and SFK-C), whereas it was identified in SFH cells derived from the PrP+/+ mice under both culture conditions, SFH-B and SFH-C (Figure 1 ▶ , lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8). In contrast, the expression of β-actin mRNA was observed in both SFK and SFH cells (Figure 1 ▶ , lanes 10, 12, 14, and 16). No products were amplified in total RNA samples processed for PCR when the reverse transcription step was omitted, confirming that a contamination of genomic DNA was excluded (Figure 1 ▶ , lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15).

Figure 1.

Nonexpression of the PrP gene in a skin fibroblast cell line established from the PrP−/− mice. Two cell lines were established from primary cultures of skin fibroblasts isolated from the PrP−/− mice (SFK) or from the PrP+/+ mice (SFH). They were maintained for 4 months in vitro before starting the experiments. The cells were incubated for 72 hours in LS medium with (SFH-B and SFK-B) or without (SFH-C and SFK-C) inclusion of 50 ng/ml of bFGF for the last 24 hours before processing for RNA preparation. Fifty nanograms of cDNA prepared from total RNA by reverse transcription (RT) was amplified by PCR using primer pairs specific for the PrP gene (lanes 1−8) or the β-actin gene (lanes 9−16) listed in Table 1 ▶ . Lanes 1 and 9 represent SFH-C cells processed for RT-PCR omitting the RT step; lanes 2 and 10, SFH-C cells processed for RT-PCR including the RT step; lanes 3 and 11, SFK-C cells processed for RT-PCR omitting the RT step; lanes 4 and 12, SFK-C cells processed for RT-PCR including the RT step; lanes 5 and 13, SFH-B cells processed for RT-PCR omitting the RT step; lanes 6 and 14, SFH-B cells processed for RT-PCR including the RT step; lanes 7 and 15, SFK-B cells processed for RT-PCR omitting the RT step; lanes 8 and 16, SFK-B cells processed for RT-PCR including the RT step. The DNA size marker (bp) is shown on the left.

Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes between SFK and SFH Cells by Analyzing a cDNA Expression Array

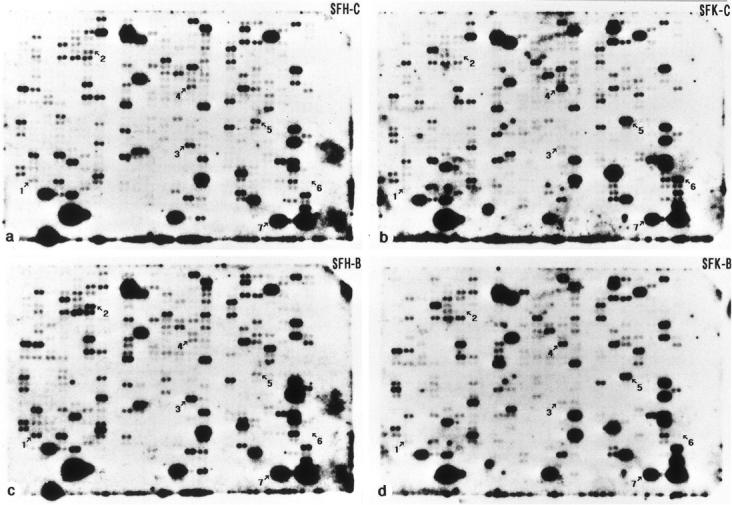

The cDNA expression array was analyzed by Southern blot hybridization with the 32P-labeled cDNA probes prepared from poly A+ RNA which was isolated from SFH-C, SFK-C, SFH-B or SFK-B cells, all of which were maintained for 4 months in vitro. Among the 597 cDNA clones, 42 genes exhibited a differential expression pattern between SFK-C and SFH-C cells (Figure 2, a and b ▶ , and Table 2 ▶ ). The expression of 15 genes including those essential for cell proliferation and adhesion, such as c-myc proto-oncogene, cyclin D1, the receptor tyrosine kinase substrate Eps8, CD44, and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, was reduced in SFK-C cells compared to the levels in SFH-C cells (Table 2) ▶ ▶ . In contrast, the expression of 27 genes including those involved in the insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) signaling pathway, such as phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) p85, IGF-binding proteins (IGFBP) -3, -5, and -6, and IGF-I, was elevated in SFK-C cells compared to the levels in SFH-C cells (Table 2) ▶ . Exposure to bFGF elevated the expression levels of 25 genes in SFH cells and 17 genes in SFK cells by up-regulating eight genes shared between both, such as 14-3-3η and the UV excision repair protein homologue MHR23B (Figure 2, a ▶ -d, and Table 2 ▶ ). Treatment with bFGF reduced the levels of expression of 15 genes in SFH cells and 22 genes in SFK cells by down-regulating 12 genes shared between both, such as cdk4/cdk6 inhibitor p18 and protein kinase C-θ (Figure 2, a ▶ -d, and Table 2 ▶ ).

Figure 2.

Southern blot hybridization of a cDNA expression array with 32P-labeled cDNA probes prepared from mRNA isolated from SFK and SFH cells. A set of filters containing 597 arrayed mouse cDNA clones of various functional classes, immobilized as a spot of duplicate dots on a nylon membrane, were hybridized with 32P-labeled cDNA probes prepared from poly A+ RNA that was isolated from bFGF-treated or untreated SFK and SFH cells maintained for 4 months in vitro: SFH-C (a), SFK-C (b), SFH-B (c), or SFK-B (d) cells. The spots indicated by arrows represent the clones of (1) the receptor tyrosine kinase substrate Eps8, (2) cyclin D1, (3) CD44, (4) phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) p85, (5) insulin-like growth factor (IGF-I), (6) serine protease inhibitor (Spi-2.2), and (7) β-actin.

Table 2.

Genes Exhibiting a Differential Expression Pattern between SFK and SFH Cells in Analysis of 597 Arrayed cDNA Clones

| Genes up-regulated or down-regulated in SFK-C cells compared to SFH-C cells | ||

|---|---|---|

| Up-regulation (27 clones) | Down-regulation (15 clones) | |

| c-ErbA proto-oncogene | ZO-1 tight junction protein | |

| Cot proto-oncogene | c-myc proto-oncogene | |

| PDGF receptor α | Cyclin B1 | |

| Golgi 4-transmembrane spanning transporter | *Cyclin D1 | |

| RNA-activating protein kinase inhibitor p58 | Thrombin receptor | |

| *Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase p85 | Transferrin receptor protein p90 | |

| Glutathione peroxidase | Transcription factor A10 | |

| Microsomal glutathione S-transferase | Matrix metalloproteinase-11 | |

| Mu 1 glutathione S-transferase | MHR23B UV excision repair protein homologue | |

| Pi 1 glutathione S-transferase | Activating transcription factor 4 | |

| Serine proteinase inhibitor SPI3 | *Eps8 receptor tyrosine kinase substrate | |

| Adipocyte differentiation-associated protein | *CD44 | |

| p45 NF-E2-related transcription factor | Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 | |

| Transcription factor S-II | IGF-binding protein-4 | |

| Monocyte chemoattractant protein-3 | Ornithine decarboxylase | |

| Growth hormone receptor | ||

| Integrin β1 | ||

| IGF-binding protein-3 | ||

| IGF-binding protein-5 | ||

| IGF-binding protein-6 | ||

| *IGF-I | ||

| TGF-β2 | ||

| Cathepsin B | ||

| Cathepsin D | ||

| *Serine protease inhibitor-2.2 | ||

| Serine protease inhibitor-2.4 | ||

| Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-3 | ||

| Genes Up-regulated or Down-regulated in SFH-B Cells Compared to SFH-C Cells | ||

| Up-regulation (25 clones) | Down-regulation (15 clones) | |

| c-myc proto-oncogene | Cot proto-oncogene | |

| Net transcription factor | Cdk4/cdk6 inhibitor p18 | |

| Lfc proto-oncogene | Prothymosin α | |

| Cyclin B2 | Protein kinase C-θ | |

| *Cyclin D1 | *Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase p85 | |

| Etoposide-induced p53 responsive mRNA | Glutathione reductase | |

| 14-3-3η | Homeobox protein-2.1 | |

| Microsomal glutathione S-transferase | Homeobox protein-8 | |

| Gadd45 | C5A receptor | |

| Serine proteinase inhibitor SPI3 | Cannabinoid receptor 2 | |

| PA6 stromal protein | P-selectin | |

| MHR23B UV excision repair protein homologue | IGF-binding protein-1 | |

| *Eps8 receptor tyrosine kinase substrate | IGF-binding protein-5 | |

| SRY-box containing gene 4 | *IGF-I | |

| Transcription factor SEF2 | FGF-7 | |

| Transcriptional enhancer factor-1 | ||

| YB1 DNA binding protein | ||

| Monocyte chemoattractant protein-3 | ||

| Insulin receptor substrate-1 | ||

| LDL receptor | ||

| *CD44 | ||

| Integrin β1 | ||

| Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 | ||

| Vimentin | ||

| Cathepsin L | ||

(Table continues)

Table 2A.

Continued

| Genes Up-regulated or Down-regulated in SFK-B Cells Compared to SFK-C Cells | |

|---|---|

| Up-regulation (17 clones) | Down-regulation (22 clones) |

| c-myc proto-oncogene | c-ErbA proto-oncogene |

| Lfc proto-oncogene | Cot proto-oncogene |

| Cyclin B1 | Cdk4/cdk6 inhibitor p18 |

| Cyclin B2 | Prothymosin α |

| Etoposide-induced p53-responsive mRNA | Protein kinase C-θ |

| Glucose regulated protein 78 | *Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase p85 |

| gp130 | Glutathione peroxidase |

| MAP kinase kinase-1 | Glutathione reductase |

| 14-3-3η | AT motif-binding factor 1 |

| Serine proteinase inhibitor SPI3 | BKLF CACCC box-binding protein |

| Matrix metalloproteinase-11 | Homeobox protein-2.1 |

| MHR23B UV excision repair protein homologue | Homeobox protein-8 |

| Adipocyte differentiation-associated protein | Bone morphogenic protein receptor |

| Transcription factor SEF2 | C5A receptor |

| Integrin β1 | Cannabinoid receptor 2 |

| Laminin receptor 1 | P-selectin |

| Serine protease inhibitor homologue J6 | IGF-binding protein-3 |

| *IGF-I | |

| TGF-β2 | |

| Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-specific serine protease CTLA-1 | |

| *Serine protease inhibitor-2.2 | |

| Serine protease inhibitor-2.4 | |

*The mRNA levels of Eps8, cyclin D1, CD44, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) p85, IGF-I, and serine protease inhibitor (Spi-2.2) in SFK and SFH cells were also analyzed by Northern blotting as shown in Figure 3A ▶ . Both SFK and SFH cells were maintained for 4 months in vitro before starting the experiments.

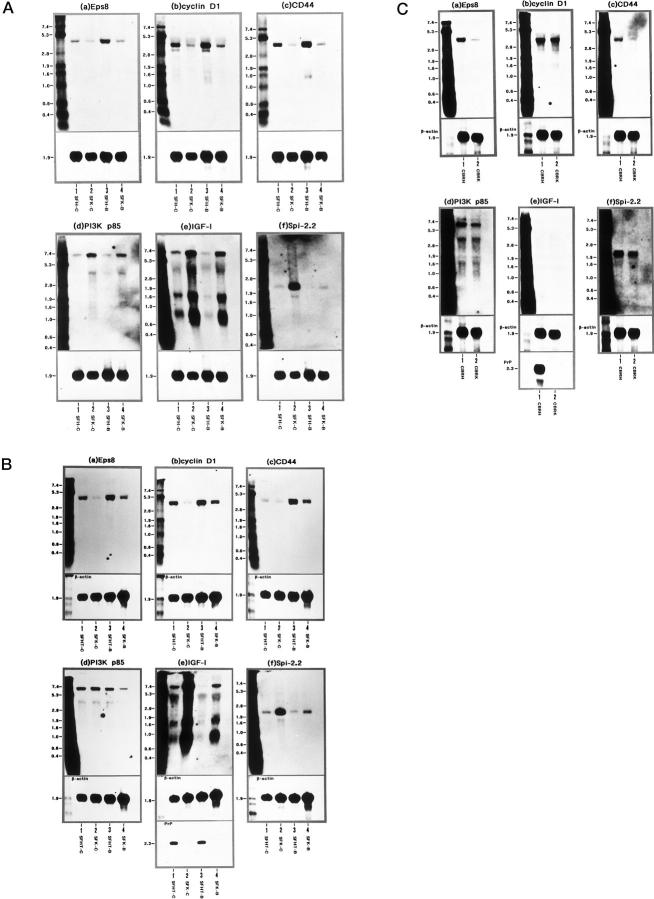

Northern Blot Analysis of Six Genes Expressed Differentially between SFK and SFH Cells

Since it is impractical to quantify all 42 genes expressed differentially between SFK and SFH cells under untreated conditions using Northern blot analysis, six clones exhibiting a great difference between both were selected in view of their potential involvement in cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival. They included three genes down-regulated in SFK-C cells versus SFH-C cells: Eps8 (Figure 2 ▶ , spot 1), cyclin D1 (Figure 2 ▶ , spot 2), and CD44 (Figure 2 ▶ , spot 3) and three genes up-regulated in SFK-C cells versus SFH-C cells: PI3K p85 (Figure 2 ▶ , spot 4), IGF-I (Figure 2 ▶ , spot 5), and the serine protease inhibitor (Spi)-2.2, a mouse equivalent to the human α1-antichymotrypsin (ACT) 23 (Figure 2 ▶ , spot 6). In Northern blotting, the levels of expression of Eps8 (4.7 kb), cyclin D1 (4.5 and 3.8 kb), and CD44 (4.7 kb) mRNAs were reduced in SFK-C cells to 33%, 28%, or 22% of those in SFH-C cells, respectively, when standardized against corresponding β-actin signals detected on the identical blots (Figure 3A, a ▶ -c, lanes 1 and 2). After exposure to bFGF, the levels of Eps8, cyclin D1, and CD44 mRNAs were elevated in SFH-B cells by 3.2-fold, 1.4-fold, or 1.9-fold, respectively, compared to those in SFH-C cells, and increased in SFK-B cells by 2.4-fold, 1.3-fold, or 2.1-fold, respectively, compared to those in SFK-C cells (Figure 3A, a ▶ -c, lanes 1–4). However, the levels of Eps8, cyclin D1, and CD44 mRNAs were much lower in SFK-B cells than those in SFH-C cells (Figure 3A, a ▶ -c, lanes 1–4). In contrast, the levels of PI3K p85 (7.0 and 4.0 kb), IGF-I (7.0, 1.6, and 0.8 kb) and Spi-2.2 (2.1 kb) mRNAs were elevated in SFK-C cells by 4.6-fold, 6.0-fold, or 25.7-fold, respectively, compared to those in SFH-C cells (Figure 3A, d ▶ -f, lanes 1 and 2). After bFGF exposure, the expression of PI3K p85, IGF-I and Spi-2.2 mRNAs was reduced in SFK-B cells to 59%, 85%, or 6% of those in SFK-C cells, and decreased in SFH-B cells to 71%, 17%, or 16% of those in SFH-C cells, respectively, with the greatest reduction of Spi-2.2 expression in SFK cells after bFGF treatment (Figure 3A, d ▶ -f, lanes 1–4).

Figure 3.

Northern blot analysis of Eps8, cyclin D1, CD44, PI3K p85, IGF-I, and Spi-2.2 mRNA expression in SFK, SFH, and SFHT cells and brain tissues isolated from the PrP−/− and PrP+/+ mice. A distinct skin fibroblast cell line, designated SFHT, was established from the PrP+/− mice. SFHT cells were incubated for 72 hours in LS medium with (SFHT-B) or without (SFHT-C) inclusion of 50 ng/ml of bFGF for the last 24 hours before processing for RNA preparation. Total RNA was extracted from SFH-C, SFHT-C, SFK-C, SFH-B, SFHT-B, or SFK-B cells, and from the whole cerebral cortices isolated from the PrP−/− mice (CBRK) or from the PrP+/+ mice (CBRH). It was processed for Northern blot analysis by hybridization with digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled DNA probes specific for the Eps8 (a), cyclin D1 (b), CD44 (c), PI3K p85 (d), IGF-I (e), or Spi-2.2 (f) gene (upper panels), followed by rehybridization with the probe specific for the β-actin gene for standardization (lower panels) and, in limited experiments, with the probe specific for the PrP gene (lowest panels). A: Lanes 1–4 represent 2 μg of total RNA isolated from SFH-C (lane 1), SFK-C (lane 2), SFH-B (lane 3), and SFK-B (lane 4) cells, all of which were maintained for 4 months in vitro before starting the experiments. B: Lanes 1–4 represent 2 μg of total RNA isolated from the following cells: SFHT-C (lane 1), SFK-C (lane 2), SFHT-B (lane 3), and SFK-B (lane 4). SFHT cells were maintained for 4 months, whereas SFK cells were maintained for 7 months in vitro before starting the experiments. The lanes in C represent 6 μg of total RNA isolated from the brain tissues CBRH (lane 1) and CBRK (lane 2). The RNA size marker (kb) is shown in the left lane.

Effects of Culture Periods and Strain Differences on Gene Expression Levels in Skin Fibroblast Cell Lines

To examine the possible effects of strain differences (129/Sv × C57BL/6J background in SFK versus C57BL/6J background in SFH) on the gene expression levels, a distinct cell line designated SFHT was established from the skin explant cultures of the heterozygous PrP+/− mice that were produced by intercross between F1 PrP+/− breeding pairs. 9-11 The expression of Eps8, cyclin D1, CD44, PI3K p85, IGF-I, and Spi-2.2 mRNAs was studied between bFGF-treated or untreated SFHT cells (SFHT-B and SFHT-C) maintained for 4 months in vitro and SFK cells (SFK-B and SFK-C) maintained for 7 months in vitro (Figure 3B, a ▶ -f, lanes 1–4). In Northern blotting, the patterns of expression of these mRNAs were almost identical between SFK cells maintained for 4 months and those maintained for 7 months in vitro (Figure 3A, a ▶ -f, and 3B, a-f, lanes 2 and 4), indicating that the culture periods might not constitute a major factor contributing to the aberrant gene expression identified in SFK cells. Furthermore, there was a high degree of similarity between the patterns of expression of these mRNAs in SFHT-C and SFK-C cells and those in SFH-C and SFK-C cells examined in the initial experiments, except that SFHT-C cells expressed a lower level of CD44 mRNA and a higher level of PI3K p85 mRNA than SFH-C cells (Figure 3A, a ▶ -f, and 3B, a-f, lanes 1 and 2). The levels of expression of Eps8, cyclin D1, and CD44 mRNAs in SFK-C cells maintained for 7 months were reduced to 6%, 9%, or 34% of those in SFHT-C cells, respectively (Figure 3B, a ▶ -c, lanes 1 and 2). In contrast, the levels of IGF-I and Spi-2.2 mRNAs were elevated in SFK-C cells by 4.9-fold or 4.2-fold, respectively, compared to those in SFHT-C cells (Figure 3B, e and f ▶ , lanes 1 and 2). PrP mRNA was undetectable in SFK cells but detectable in SFHT cells (Figure 3B ▶ e, lanes 1–4). These results suggest that the aberrant gene expression identified in SFK cells is unlikely to be due to the effects of strain differences.

Differential Gene Expression in Brain Tissues of the PrP−/− Mice and PrP+/+ Mice

To evaluate the possibility that the differential gene expression between SFK and SFH cells might represent a fibroblast cell line-specific observation, the expression of Eps8, cyclin D1, CD44, PI3K p85, IGF-I, and Spi-2.2 mRNAs was studied in the brain tissues of the cerebrum isolated from the PrP−/− mice (CBRK) and the PrP+/+ mice (CBRH) from which SFK or SFH cells originated. In Northern blotting, the levels of expression of Eps8 and CD44 mRNAs in CBRK were reduced to 20% or 18% of those in CBRH, when standardized against corresponding β-actin signals detected on the identical blots (Figure 3C, a and c ▶ , lanes 1 and 2). Both PI3K p85 and Spi-2.2 mRNA levels in CBRK were decreased slightly to 83% or 88% of those in CBRH, whereas cyclin D1 mRNA expression was not significantly different between both (Figure 3C, b, d, and f ▶ , lanes 1 and 2). IGF-I mRNA was identified in neither of them, whereas PrP mRNA was detectable in CBRH but undetectable in CBRK (Figure 3C ▶ e, lanes 1 and 2).

Discussion

By analyzing a cDNA expression array containing 597 clones, this study showed that a number of biologically important genes exhibited a differential expression pattern between two fibroblast cell lines: SFK derived from the PrP−/− mice and SFH derived from the PrP+/+ mice. When SFK cells were compared with SFH cells without bFGF treatment, the expression of 15 genes, including those essential for cell proliferation and adhesion, was reduced, whereas the expression of 27 genes, including those involved in the IGF-I signaling pathway, was elevated. The patterns of induction or reduction of gene expression after exposure to bFGF showed a considerable overlap between both. Among the differentially expressed genes, Northern blot analysis verified a significant down-regulation of Eps8, cyclin D1, and CD44 mRNAs and a substantial up-regulation of PI3K p85, IGF-I and Spi-2.2 mRNAs in SFK cells, supporting the validity of the cDNA expression array analysis for screening the differential gene expression. The observations on SFHT cells established from the PrP+/− mice and SFK cells maintained for a longer period in culture indicated that the aberrant gene expression identified in SFK cells is unlikely to be due to the effects of culture periods and strain differences, but is most likely to be attributable to the homozygous disruption of the PrP gene in these cells. Furthermore, both Eps8 and CD44 mRNA levels were reduced greatly in the cerebral tissues isolated from the PrP−/− mice compared to those of the PrP+/+ mice. These results suggest that the PrPC protein plays an important role in regulating gene expression involved in cell proliferation, differentiation and survival, both in vitro and in vivo, because these genes encode key molecules located within or very close to the Ras and Rac signaling cascades.

The Ras proteins, activated after cell exposure to growth factors, integrate a number of downstream effectors, leading to an activation of the Raf/MAP kinase pathway, the Ral-GDS pathway, and the PI3K pathway. 24 Eps8 is originally identified as a widely expressed substrate for the receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). 25 Its overexpression in cultured fibroblasts enhances mitogenic responsiveness to endothelial growth factor. 25 Eps8 mRNA and protein expression is induced markedly in cultured fibroblasts by exposure to serum or phorbol esters, whereas it is suppressed in C2C12 myoblast cells after terminal differentiation. 26 Eps8 has a Src homology region 3 (SH3) domain that functions as an adapter, assembling intracellular signal-transducing molecules with RTKs. 25 Eps8 plays a pivotal role in signal transduction from both Ras and PI3K to Rac, a member of the subfamily of Rho-GTPases. 27 The Rac proteins that constitute the NADPH oxidase complex and act as a regulator of actin cytoskeletal reorganization have a role in cell cycle progression by activating the cyclin D1 promoter after the generation of intracellular reactive oxygen species through NF-κB activation. 28 Cyclin D1 expression is up-regulated in MCF7 human breast cancer cells by exposure to IGF-I, followed by hyperphosphorylation of a retinoblastoma protein Rb, whereas it is suppressed by PI3K-specific inhibitors. 29 CD44, a cell surface glycoprotein expressed in both hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cell types, is involved in cell adhesion by interacting with the extracellular matrix glycosaminoglycans fibronectin, laminin, and collagen. The expression of CD44 protein or its alternatively spliced variants is elevated in certain tumor cells with metastatic potential and in Ras-transformed fibroblasts in culture. 30 All of these observations could support the hypothesis that the down-regulation of Eps8, cyclin D1, and CD44 in SFK cells might reflect a functional impairment in the Ras and Rac signaling pathways in these cells.

The PI3K protein is composed of a 110-kd catalytic subunit (p110) and an 85-kd regulatory subunit (p85), the latter containing one SH3 domain and two SH2 domains by which it links to multiple signaling components. The PI3K protein, located immediately downstream from Ras, plays a role in insulin-stimulated glucose transport, exocytosis, neurite outgrowth, prevention of apoptosis, and cell cycle progression. 24 The downstream targets of PI3K are the Rac proteins, the ribosomal protein kinase p70S6K, and the serine/threonine protein kinase PKB/Akt. IGF-I activates PI3K, followed by activation of PKB/Akt, which promotes IGF-I-dependent survival of cerebellar neurons in culture. 31 Spi-2.2, a mouse homologue of the human ACT, belongs to a multigene family composed of closely related Spi-encoding genes derived by ancestral gene duplication. The expression of both Spi-2.1 and Spi-2.3 genes are up-regulated by growth hormone (GH) or by IGF-I, whereas Spi-2.2 gene expression is not GH-dependent but is induced after acute inflammatory reactions through activation of a panel of signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) proteins. 23,32 IGF-I stimulates the release of ACT in MCF7 cells. 33 All of these observations put forth a possible scenario that the up-regulated expression of PI3K p85, IGF-I, and Spi-2.2 mRNAs in SFK cells might represent a compensatory response to the reduced levels of cyclin D1 to maintain the cellular biological functions mediated by the IGF-I signaling pathway. 34 The regulatory mechanisms underlying IGF-I gene expression are highly complex, and include the use of alternative promoters acting on multiple initiation sites, differential RNA splicing, polyadenylation, and translation. 35 The biological activities of IGF-I are regulated by its half-life and affinity for specific receptors, which are affected by IGFBPs. 35 IGFBPs are cleaved by a family of serine proteases into non-IGF-I-binding fragments. 36 It is worth noting that the expression of a panel of IGFBP mRNAs is found to be elevated in SFK cells.

The mechanisms by which an absence of the PrPC protein in SFK cells deregulates the expression of a battery of genes located in the Ras and Rac signaling pathways remain unknown. The PrPC protein is enriched in a specialized compartment consisting of detergent-insoluble, cholesterol-rich membranous microdomains called caveolae-like domains (CLDs) or rafts, where a battery of signaling molecules including platelet-derived growth factor and endothelial growth factor receptors, Ras, PI3K, and nitric oxide synthase are clustered. 37,38 PrPC interacts with PrPSc in this compartment during the formation of nascent PrPSc protein. 37,38 PrP-deficient cells in culture showed an inability to deal with oxidative stress due to reduced activity of Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase, suggesting that the function of PrPC is important for cellular resistance to oxidative stress. 4,39 A recent study using hippocampal neuronal progenitor cell lines isolated from Rikn PrP−/− mice has revealed that serum removal from these cultures facilitates apoptosis. 13 Another study has shown that neuronal nitric oxide synthase is lost from the rafts in cerebellar tissues of adult Zur PrP−/− mice. 40 All of these observations suggest that PrPC might play a role in the organization of signaling complexes in CLDs (rafts), and the deficiency of its function might disturb the CLD- (raft-) associated signal transduction that is pivotal for protection against oxidative stress and apoptosis, or for synaptic transmission, although further studies are required to evaluate this hypothesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Kazuhiro Kurohara, Motohiro Yukitake, and Kimiko Tategami for their invaluable help.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Jun-ichi Satoh, Division of Neurology, Department of Internal Medicine, Saga Medical School, 5–1-1 Nabeshima, Saga 849-8501, Japan. E-mail: satoj1@post.saga-med.ac.jp.

Supported in part by a grant from the Ichiro Kanehara Foundation.

References

- 1.Prusiner SB: Prions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998, 95:13363-13383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bendheim PE, Brown HR, Rudelli RD, Scala LJ, Goller NL, Wen GY, Kascsak RJ, Cashman NR, Bolton DC: Nearly ubiquitous tissue distribution of the scrapie agent precursor protein. Neurology 1992, 42:149-156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kretzschmar HA, Prusiner SB, Stowring LE, DeArmond SJ: Scrapie prion proteins are synthesized in neurons. Am J Pathol 1986, 122:1-5 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown DR, Qin K, Herms JW, Madlung A, Manson J, Strome R, Fraser PE, Kruck T, von Bohlen A, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Giese A, Westaway D, Kretzschmar H: The cellular prion protein binds copper in vivo. Nature 1997, 390:684-687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Viles JH, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB, Goodin DB, Wright PE, Dyson HJ: Copper binding to the prion protein: structural implications of four identical cooperative binding sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999, 96:2042-2047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Büeler H, Fischer M, Lang Y, Bluethmann H, Lipp H-P, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB, Aguet M, Weissmann C: Normal development and behaviour of mice lacking the neuronal cell-surface PrP protein. Nature 1992, 356:577-582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Büeler H, Aguzzi A, Sailer A, Greiner R-A, Autenried P, Aguet M, Weissman C: Mice devoid of PrP are resistant to scrapie. Cell 1993, 73:1339-1347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manson JC, Clarke AR, Hooper ML, Aitchison L, McConnell I, Hope J: 129/Ola mice carrying a null mutation in PrP that abolishes mRNA production are developmentally normal. Mol Neurobiol 1994, 8:121-127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakaguchi S, Katamine S, Shigematsu K, Nakatani A, Moriuchi R, Nishida N, Kurokawa K, Nakaoke R, Sato H, Jishage K, Kuno J, Noda T, Miyamoto T: Accumulation of proteinase K-resistant prion protein (PrP) is restricted by the expression level of normal PrP in mice inoculated with a mouse-adapted strain of the Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease agent. J Virol 1995, 69:7586-7592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakaguchi S, Katamine S, Nishida N, Moriuchi R, Shigematsu K, Sugimoto T, Nakatani A, Kataoka Y, Houtani T, Shirabe S, Okada H, Hasegawa S, Miyamoto T, Noda T: Loss of cerebellar Purkinje cells in aged mice homozygous for a disrupted PrP gene. Nature 1996, 380:528-531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishida N, Tremblay P, Sugimoto T, Shigematsu K, Shirabe S, Petromilli C, Erpel SP, Nakaoke R, Atarashi R, Houtani T, Torchia M, Sakaguchi S, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB, Katamine S: A mouse prion protein transgene rescues mice deficient for the prion protein gene from Purkinje cell degeneration and demyelination. Lab Invest 1999, 79:689-697 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore RC, Lee IY, Silverman GL, Harrison PM, Strome R, Heinrich C, Karunaratne A, Pasternak SH, Chishti MA, Liang Y, Mastrangelo P, Wang K, Smit AFA, Katamine S, Carlson GA, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB, Melton DW, Tremblay P, Hood LE, Westaway D: Ataxia in prion protein (PrP)-deficient mice is associated with upregulation of the novel PrP-like protein doppel. J Mol Biol 1999, 292:797-817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuwahara C, Takeuchi AM, Nishimura T, Haraguchi K, Kubosaki A, Matsumoto Y, Saeki K, Matsumoto Y, Yokoyama T, Itohara S, Onodera T: Prions prevent neuronal cell-line death. Nature 1999, 400:225-226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collinge J, Whittington MA, Sidle KCL, Smith CJ, Palmer MS, Clarke AR, Jefferys JGR: Prion protein is necessary for normal synaptic function. Nature 1994, 370:295-297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whittington MA, Sidle KCL, Gowland I, Meads J, Hill AF, Palmer MS, Jefferys JGR, Collinge J: Rescue of neurophysiological phenotype seen in PrP null mice by transgene encoding human prion protein. Nat Genet 1995, 9:197-201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lledo P-M, Tremblay P, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB, Nicoll RA: Mice deficient for prion protein exhibit normal neuronal excitability and synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996, 93:2403-2407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tobler I, Gaus SE, Deboer T, Achermann P, Fischer M, Rülicke T, Moser M, Oesch B, McBride PA, Manson JC: Altered circadian activity rhythms and sleep in mice devoid of prion protein. Nature 1996, 380:639-642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen C, Rocha D, Granjeaud S, Baldit M, Bernard K, Naquet P, Jordan BR: Differential gene expression in the murine thymus assayed by quantitative hybridization of arrayed cDNA clones. Genomics 1995, 29:207-216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao N, Hashida H, Takahashi N, Misumi Y, Sakaki Y: High-density cDNA filter analysis: a novel approach for large-scale, quantitative analysis of gene expression. Gene 1995, 156:207-213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Satoh J-I, Yukitake M, Kurohara K, Nishida N, Katamine S, Miyamoto T, Kuroda Y: Cultured skin fibroblasts isolated from mice devoid of the prion protein gene express major heat shock proteins in response to heat stress. Exp Neurol 1998, 151:105-115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Satoh J-I, Kuroda Y: Differential gene expression between human neurons and neuronal progenitor cells in culture: an analysis of arrayed cDNA clones in NTera2 human embryonal carcinoma cell line as a model system. J Neurosci Methods 2000, 94:155-164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Satoh J-I, Kurohara K, Yukitake M, Kuroda Y: Constitutive and cytokine-inducible expression of prion protein gene in human neural cell lines. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1998, 57:131-139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inglis JD, Lee M, Davidson DR, Hill RE: Isolation of two cDNAs encoding novel α1-antichymotrypsin-like proteins in a murine chondrocytic cell line. Gene 1991, 106:213-220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gille H, Downward J: Multiple Ras effector pathways contribute to G1 cell cycle progression. J Biol Chem 1999, 274:22033-22040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fazioli F, Minichiello L, Matoska V, Castagnino P, Miki T, Wong WT, Di Fiore PP: Eps8, a substrate for the epidermal growth factor receptor kinase, enhances EGF-dependent mitogenic signals. EMBO J 1993, 12:3799-3808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallo R, Provenzano C, Carbone R, Di Fiore PP, Castllani L, Falcone G, Alema S: Regulation of the tyrosine kinase substrate Eps8 expression by growth factors, v-Src and terminal differentiation. Oncogene 1997, 15:1929-1936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scita G, Nordstrom J, Carbone R, Tenca P, Giardina G, Gutkind S, Bjarnegård M, Betsholtz C, Di Fiore PP: EPS8 and E3B1 transduce signals from Ras to Rac. Nature 1999, 401:290-293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Page K, Li J, Hodge JA, Liu PT, Hoek TLV, Becker LB, Pestell RG, Rosner MR, Hershenson MB: Characterization of a Rac1 signaling pathway to cyclin D1 expression in airway smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 1999, 274:22065-22071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dufourny B, Alblas J, van Teeffelen HAAM, van Schaik FMA, van der Bung B, Steenbergh PH, Sussenbach JS: Mitogenic signaling of insulin-like growth factor I in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells requires phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and is independent of mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem 1997, 272:31163-31171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kogerman P, Sy M-S, Culp LA: CD44 protein levels and its biological activity are regulated in Balb/c 3T3 fibroblasts by serum factors and by transformation with the ras but not with the sis oncogene. J Cell Physiol 1996, 169:341-349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dudek H, Datta SR, Franke TF, Birnbaum MJ, Yao R, Cooper GM, Segal RA, Kaplan DR, Greenberg ME: Regulation of neuronal survival by the serine-threonine protein kinase Akt. Science 1997, 275:661-665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berry SA, Bergad PL, Stolz AM, Towle HC, Schwarzenberg SJ: Regulation of Spi 2.1 and 2.2 gene expression after turpetine inflammation: discordant responses to IL-6. Am J Physiol 1999, 276:C1374–C1382 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Confort C, Rochefort H, Vignon F: Insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) stimulates the release of α1-antichymotrypsin and soluble IGF-II/mannose 6-phosphate receptor from MCF7 breast cancer cells. Endocrinology 1995, 136:3759-3766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Furlanetto RW, Harwell SE, Frick KK: Insulin-like growth factor-I induces cyclin D1 expression in MG63 human osteosarcoma cells in vitro. Mol Endocrinol 1994, 8:510-517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.LeRoith D, Robert CT, Jr: Insulin-like growth factors. Ann NY Acad Sci 1993, 692:1-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nam TJ, Busby WHJr, Clemmons DR: Human fibroblasts secrete a serine protease that cleaves insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-5. Endocrinology 1994, 135:1385–1391 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Naslavsky N, Stein R, Yanai A, Friedlander G, Taraboulos A: Characterization of detergent-insoluble complexes containing the cellular prion protein and its scrapie isoform. J Biol Chem 1997, 272:6324-6331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okamoto T, Schlegel A, Scherer PE, Lisanti MP: Caveolins, a family of scaffolding proteins for organizing “preassembled signaling complexes” at the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem 1998, 273:5419-5422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown DR, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ, Schmidt B, Kretzschmar HA: Prion protein-deficient cells show altered response to oxidative stress due to decreased SOD-1 activity. Exp Neurol 1997, 146:104-112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keshet GI, Ovadia H, Taraboulos A, Gabizon R: Scrapie-infected mice and PrP knockout mice share abnormal localization and activity of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. J Neurochem 1999, 72:1224-1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]