Abstract

A growing body of evidence supports the hypotheses that retinoic acid receptor β2 (RAR β2) is a tumor suppressor gene. Although the loss of RAR β2 expression has been reported in many malignant tumors, including breast cancer, the molecular mechanism is still poorly understood. We hypothesized that loss of RAR β2 activity could result from multiple factors, including epigenetic modification and loss of heterozygosity (LOH). Using methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction and LOH analysis, we found that biallelic inactivation via epigenetic changes of both maternal and paternal alleles, or epigenetic modification of one allele combined with genetic loss of the remaining allele, could completely suppress RAR β2 expression in breast cancer. Thus, it is possible that substantial numbers of human cancers arise through suppressor gene silencing via epigenetic mechanisms that inactivate both alleles. Because of this, chromatin-remodeling drugs may provide a novel strategy for cancer prevention and treatment.

Retinoids, a group of structural and functional analogues of vitamin A, are known to mediate cellular signals critical for embryonic morphogenesis, cell growth, and differentiation. The use of retinoids to suppress tumor development has been evaluated in several animal models of carcinogenesis, including models of skin, breast, oral cavity, lung, hepatic, gastrointestinal, prostatic, and bladder cancers. 1 Clinically, retinoids are able to reverse premalignant lesions and inhibit the development of primary tumors. 2-5

The regulation of cell growth and differentiation by retinoids in normal, premalignant, and malignant cells is thought to result from both direct and indirect effects on retinoid gene expression mediated by nuclear receptors: retinoic acid receptors (RARs) and retinoid X receptors (RXRs). These receptors are ligand-activated transcription factors and members of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily, and both consist of three subtypes: α, β, and γ. Retinoid receptors activate transcription in a ligand-dependent manner by binding as RAR/RXR heterodimers or RXR homodimers to retinoic acid response elements (RAREs) located in the promoter regions of target genes.

One of the target genes of retinoid receptors is RAR β, which has a central role in the growth regulation of mammary epithelial cells. RAR β maps to chromosome 3p24, a region that exhibits a high frequency (45%) of loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in primary breast tumors. 6 Retroviral transduction of breast tumor cell lines with RAR β2 results in inhibition of tumor cell proliferation. 7 RAR β2 levels were found to be decreased or suppressed in a number of malignant tumors, including lung carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, and breast cancer. 8-10 These findings suggest that RAR β2 plays an important role in limiting the growth of many cell types, and that the loss of this regulatory activity is associated with tumorigenesis. To understand why RAR β activity is down-regulated or lost in malignant tumors, intense efforts have been directed at identifying possible alterations that affect either the RAR β2 promoter or its regulatory factors. 7,10,11 Intriguingly, methylation of the RAR β2 promoter region has recently been described in breast cancer. 12-14 The aim of this study was to further elucidate the mechanism of complete RAR β2 inactivation in breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Tissue Samples

Human female breast cancer cell lines T-47 D and MRK-nu-1 were obtained from Japan Cancer Research Resources Bank (Tokyo, Japan). A total of 45 paired tumor and peripheral blood samples were collected from the Affiliated Kihoku Hospital of Wakayama Medical College, Japan. Tumor samples were snap-frozen at −70°C immediately after resection. All specimens underwent histological examination by two pathologists to confirm diagnosis of adenocarcinoma through evaluation of more than 90% of sample tumor cells.

DNA and RNA Extraction

DNA and RNA extractions were performed using the QIAamp Tissue Kit and the Rneasy Kit (both Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Microsatellite Analysis of LOH

Analysis of polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based LOH was performed by using three microsatellite markers flanking chromosome 3p24: D3S 1283, D3S 1293, and D3S 1286. All primer sequences and their locations were obtained from human genetic linkage maps. PCR was carried out in reaction volumes of 50 μl containing 100 ng genomic DNA as template, 1× PCR buffer, 200 μmol/L dNTP mix, 300 nmol/L forward primer, 300 nmol/L reverse primer, and 2.5 units Taq DNA polymerase. Each microsatellite marker was amplified from paired normal and tumor DNA samples by PCR under the following reaction conditions: 94°C for 2 minutes for one cycle; followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 minute, 52–60°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 45 seconds, with a final incubation step at 72°C for 5 minutes. Ten-microliter aliquots of the PCR products were then loaded onto 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gels, and separated by electrophoresis at 350 volts for 3 to 6 hours. Gels were stained using the PlusOne DNA Silver Staining Kit in a GeneStain Automated Gel Stainer (Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Two observers analyzed the staining results visually and recorded allele imbalance when there was clear reduction in the intensity of one allele amplified from tumor DNA samples.

Mutation Analysis

To amplify the region containing the βRARE, we used the following primer pairs: sense primer 5′-GGA GTT GGT GAT GTCAGA CTA G-3′, position 737–758; and antisense primer 5′-GAT CCC AAG TTC TCC TTC CAA G-3′, position 1062–1040 of RAR β2 promoter region (GenBank accession no. X56849). After an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 1 minute, DNA was amplified through 35 cycles of 30 seconds denaturing at 94°C, 30 seconds annealing at 60°C, and 45 seconds extension at 72°C in a DNA Thermal Cycler 480 (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, CT). Expected fragment length was 324 bp. PCR fragments were purified using the QIAquick Purification kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA), and 1-μl aliquots used in sequencing reactions using the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). After purification using Centri-Sep Spin Columns, samples were resuspended in 20 μl of template suppression reagent for sequence analysis in an Applied Biosystems Model 310 Sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Sequencing was performed on both DNA strands.

Evaluation of Methylation Status of the RAR β2 Promoter Region

Approximately 1.0 μg of each DNA sample was bisulfite modified using a commercial kit (CpGenome DNA modification kit, Oncor Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Bisulfite-modified DNA was PCR amplified by using the primer pairs RARβ-M and RARβ-U, as previously described. 15 Samples positive for RAR β2 promoter region methylation were confirmed using the PCR-based HpaII restriction enzyme assay according to the procedure detailed by Kane et al. 16 Briefly, genomic DNA samples were digested with HpaII or MspI, or incubated without restriction enzymes. The 550-bp region upstream of the RARβ2 gene, which contains 5 HpaII sites, was then amplified using the primer pairs: forward primer, 5′-TGC TCA ACG TGA GCC AGG A-3′, position 554–572; and reverse primer, 5′-AGG CTT GCT CGG CCA ATC CA-3′, position 1105–1086 of RAR β2 promoter region (GenBank accession no. X56849).

Cell Culture

RPMI 1640 growth medium was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Cultures were grown at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were seeded at 4 × 10 4 cells per T 75 flask on day 0 and treated for 24 hours on days 2, 3, and 4 with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-Aza-CdR). On day 6, cells were harvested for analysis of RAR β2 promoter region methylation status and for RAR β2 protein production.

Reverse Transcription (RT)-PCR for RAR β2

One-microgram aliquots of RNA were reverse-transcribed in 20-μl reaction volumes at 42°C using the SuperScript Preamplification System (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD), and 2-μl aliquots of cDNA then subjected to RT-PCR. Primers for exon 5 (sense primer 5′-ATC GAT GCC AAT ACT GTC GA-3′, position 503–522) and exon 6 (antisense primer 5′-GAC TCG ATG GTC AGC ACT G-3′, position 744–426) were designed according to published RAR β2 sequence 17 (GenBank accession no. AF157483). RT-PCR with actin primers (sense primer 5′-GCT CGT CTG CGA CAA CGG CTC-3′ and antisense primer 5′ -CAA ACA TGA TCT GGG TCA TCT TCT C-3′) was used as an internal RNA control. PCR products were analyzed on 2% agarose gels.

Western Blot Analysis

Total protein extracts were prepared in lysis buffer containing 40 mmol/L HEPES (pH 7.4), 1% triton-X 100, 10% glycerol, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Ten-microgram aliquots of total protein from each sample were analyzed in 10 to 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature using 5% skim milk (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) and then incubated overnight at 4°C with RAR β primary mouse monoclonal antibody raised against a C-terminal RARβ epitope (SA-179; Biomol Research Laboratories, Plymouth Meeting, PA) at a dilution of 1:1000. After three 8-minute washes with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.04% Tween 20, membranes were incubated for 1 hour with horseradish peroxidase-coupled anti-IgG secondary antibody (1:1000). An actin immunoblot (1:200 dilution; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was used to confirm the presence of protein in the cell extracts. Blots were visualized using the ECL Western blotting analysis system (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK) according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Results

Loss of Heterozygosity (LOH) on Chromosome 3p24

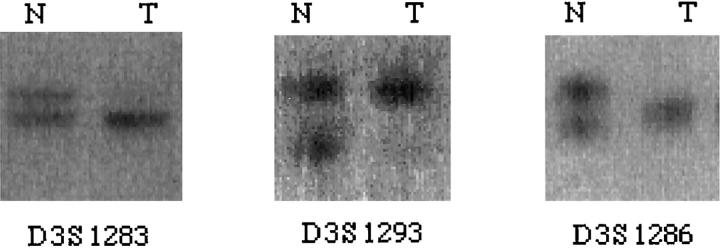

We performed LOH analysis on chromosome 3p24 at three loci: D3S 1283, D3S 1293, and D3S 1286. All patients were informative for at least one locus, and the overall LOH frequency at 3p24 involving at least one marker was 24% (11/45). When individual markers were analyzed, LOH was found in 24% of breast cancers at D3S 1283, 32% at D3S 1293, and 24% at D3S 1286 (Figure 1) ▶ . Retention of both maternal and paternal alleles was detected in both T-47D and MRK-nu-1 cell lines (data not shown).

Figure 1.

LOH at chromosome 3p24 in breast cancer. Three microsatellite markers were analyzed for LOH in surgical specimens obtained from breast cancer patients and compared with matched peripheral blood leukocyte samples. Representative examples of heterozygotes with LOH are shown. N, normal DNA (leukocyte DNA); T, tumor DNA.

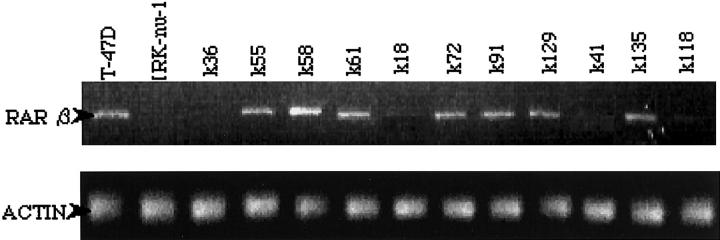

Loss of RAR β2 Expression in Breast Cancer Cell Lines and Tumors with LOH

We analyzed RAR β2 expression in the two tumor cell lines and in 11 breast cancers that exhibited LOH using RT-PCR and Western blot analysis. RAR β2 mRNA expression was observed in T-47D cells, and in 7 of 11 tumors (64%; Figure 2 ▶ ). This result suggests that LOH alone cannot completely suppress RAR β2 expression.

Figure 2.

RT-PCR analysis of RAR β2 expression in breast cancer cell lines and tumors. T-47D and MRK-nu-1 cell lines were untreated by 5-Aza-CdR. All patient samples used exhibited LOH. RAR β2 mRNA expression was not observed in MRK-1 cells, or in cases k36, k41, k18, and k118.

Methylation Status of RARβ Gene in Breast Cancer Cell Lines and Tumors with LOH

To examine the molecular mechanisms of RAR β2-loss in breast cancer, we sequenced the RAR β2 gene promoter for evidence of mutations. No mutations were found in RAR β2 promoter region at positions 737 to 1062 (GenBank accession no. X56849) in any of the breast cancer tumors or cell lines. We then examined the methylation status of the RAR β2 promoter region for evidence of epigenetic change. Using methylation-specific PCR, both methylated and unmethylated alleles were found in the T-47D cell line, but only methylated alleles were demonstrated in the MRK-nu-1 cell line (Figure 4A) ▶ .

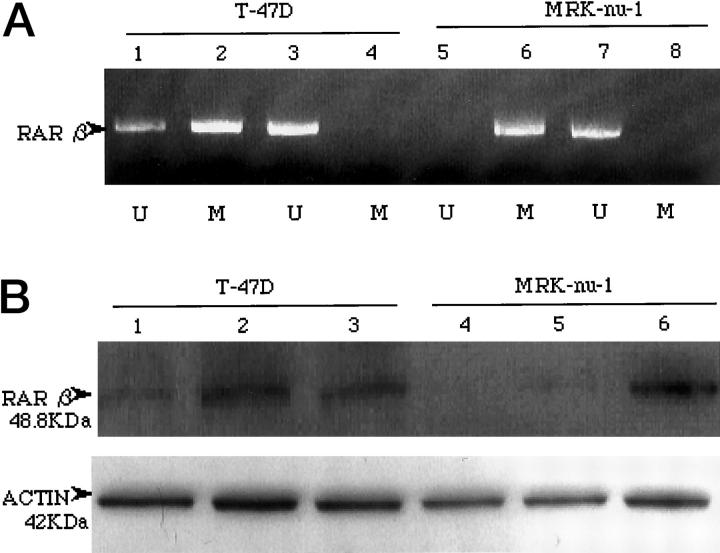

Figure 4.

Treatment with 5-Aza-CdR induces demethylation and RAR β2 protein expression in breast cancer cell lines. T-47D and MRK-nu-1 cells were left untreated or incubated for 3 days with 5-Aza-CdR. A: Methylation-specific PCR analysis of cell line DNA before (lanes 1, 2, 5, and 6) and after (lanes 3, 4, 7, and 8) 5.0 μmol/L 5-Aza-CdR treatment. Extracted DNA was treated with bisulfite as described in the text, and amplified by PCR using primers specific for methylated (M lanes) and unmethylated (U lanes) DNA. The presence of a 146-bp PCR product in lanes marked U indicates that the corresponding RAR β2 gene is unmethylated; product in lanes marked M indicates that RAR β2 is methylated. B: Western blot analysis of RAR β2 protein expression in cell lines before and after treatment for 3 days with 1.0 μmol/L (lanes 2 and 5) and 5.0 μmol/L (lanes 3 and 6) 5-Aza-CdR, in comparison with untreated cells (lanes 1 and 4).

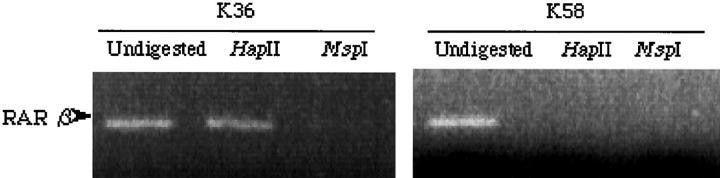

It has been reported that microdissected breast stroma and normal epithelial cells are unmethylated at RAR β2. 13 However, methylation-specific PCR analysis alone cannot determine whether unmethylated alleles were maintained in tumor cells as amplification could have occurred from normal epithelial or stromal cells mixed with the tumor cells. Therefore, we used the PCR-based HpaII restriction enzyme assay to evaluate the methylation status of the remaining RAR β2 alleles in the 11 breast cancer tumor samples with LOH. The four cases without RAR β2 mRNA expression were found to contain methylated alleles. In contrast, the seven cases with RAR β2 mRNA expression contained unmethylated RAR β2 alleles. Figure 3 ▶ shows representative examples of results from methylated and unmethylated alleles.

Figure 3.

Analysis of RAR β2 promoter methylation status of breast tumor samples. PCR amplification products resulting from the RAR β2 promoter region before or after digestion are shown. Case k36, methylated; k58, unmethylated.

5-Aza-CdR Induces Demethylation of the RAR β2 Promoter and Reactivates/Up-Regulates RAR β2 Gene Expression

To determine whether RAR β2 promoter methylation could be further linked to loss of RAR β2 expression, the cancer cell lines were treated with the demethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-Aza-CdR). Treatment of cells with 1.0 and 5.0 μmol/L 5-Aza-CdR for 3 days led to complete demethylation of both the T-47D and MRK-nu-1 cell lines (Figure 4A) ▶ . Moreover, as shown in Figure 4B ▶ , 5-Aza-CdR successfully restored RAR β2 protein expression in MRK-nu-1 cells that harbored methylated promoter regions. Up-regulation of RAR β2 protein expression was observed in T-47D cells that previously contained both methylated and unmethylated promoters. These data indicate that RAR β2 promoter methylation leads to the down-regulation or loss of RAR β2 transcription in breast cancer cell lines.

Biallelic Inactivation of RAR β2 in Breast Cancer

By Western blot analysis, small amounts of wild-type RAR β2 protein were detectable in T-47D but not MRK-nu-1 cells (Figure 4B) ▶ , demonstrating that both wild-type RAR β2 alleles were inactivated in MRK-nu-1. In many cancers, biallelic inactivation of suppressor genes is the result of mutation of one allele, followed by deletion of the remaining allele. 18 This two-step process can be observed as LOH involving polymorphic markers linked to suppressor gene loci. 18 When LOH at the RAR β2 locus was analyzed in the breast cancer cell lines, retention of both maternal and paternal alleles was detected in both T-47D and MRK-nu-1 cells. After 5-Aza-CdR treatment, RAR β2 induction was detected in the MRK-nu-1 cell line, and RAR β2 up-regulation observed in the T-47D cell line. Thus, monoallelic inactivation in T-47D and biallelic inactivation in MRK-nu-1 appears to be caused by epigenetic modification. Furthermore, of the 11 tumor samples that exhibited LOH, the four cases with methylation showed complete loss of RAR β2 transcripts. Therefore, biallelic inactivation of suppressor genes may also result from epigenetic modification of one allele followed by gene deletion of the remaining allele.

Discussion

Reduced RAR β2 mRNA expression has been observed in several solid tumors, including lung carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and breast cancer. 8-10 A growing body of evidence supports the hypotheses that the RAR β2 gene is a tumor suppressor gene 19-21 and that the chemopreventive effects of retinoids are due to RAR β2 induction. 22 However, the mechanism of RAR β2 suppression remains largely unknown.

The RAR β2 gene promoter includes a RARE motif that can be activated by RAR/retinoid X receptor (RXR) heterodimers. However, in breast cancer cell lines, retinoic acid does not induce RAR β2 gene expression, despite tumor cells being able to trans-activate an exogenous βRARE. 23 These facts support the concept that the endogenous receptors contain point mutations or polymorphisms that disrupt function. However, in our present study, we detected no mutations or polymorphisms within the βRARE promoter. Likewise, no mutations were found in the promoter region of RAR β2 in HeLa cervical carcinoma cells that also lack RAR β2. 24 Thus, it is likely that the RAR β2 promoter region is not a target for mutation in many cancers, and other mechanisms for RAR β2 suppression should be considered. Cote et al 15 first suggested that methylation may be a mechanism responsible for the lack of RAR β2 gene expression in a colon carcinoma cell line. Data presented in this report demonstrate that epigenetic silencing of the RAR β2 gene promoter may be an important event in breast cancer, and that an epigenetic silencing mechanism was closely associated with RAR β2 gene promoter methylation.

RAR β2 is located at chromosome 3p24, and LOH of chromosome 3p24 is a common event in breast cancer. 6 Therefore, we also performed LOH analysis on the cell line and tumor samples using microsatellite markers. It is thought that LOH alone cannot completely suppress RAR β2 expression, as many genes can be expressed monoallelically. 25,26 Indeed, the lack of correlation between retinoic acid receptor β2 expression and LOH at chromosome 3p24 has been demonstrated in esophageal cancer. 27 In our present study, seven breast cancer samples with LOH at 3p24 showed RAR β2 expression, which suggested that RAR β2 can be expressed in a monoallelic fashion.

Biallelic inactivation has been demonstrated for many suppressor genes, such as p53 and APC, and is usually caused by mutational inactivation of one allele accompanied by deletion or loss of the cognate wild-type allele, via mechanisms that result in LOH. 18 However, we found that biallelic inactivation of the RAR β2 gene could result either from epigenetic inactivation of both parental alleles, or from epigenetic modification of one allele and deletion of the remaining allele. These findings suggest that epigenetic gene inactivation is a highly efficient mechanism of silencing RAR β2 gene expression. Transcriptional repression by DNA methylation can be mediated through a sequence-independent process that involves changes in chromatin structure and histone acetylation levels. Binding of the transcriptional repressor MeCP2 to methylated DNA is followed by recruitment of a complex containing a transcriptional corepressor and a histone deacetylase. Deacetylation of histones is associated with reduced transcription levels, perhaps through tighter nucleosomal packing. 28 On RXR-RAR heterodimer binding to RARE, chromatin structure undergoes dynamic, reversible changes in and around the RAR β2 promoter. 29 Therefore, elucidation of mechanisms underlying epigenetic inactivation of RAR β2 may be relevant to the understanding of many different types of human cancer.

This study established that RAR β2 promoter region methylation was strongly associated with epigenetic gene silencing, and that the silencing mechanism was sufficient to accomplish biallelic inactivation of the RAR β2 gene that could be reversed by exposure to demethylating agents. Knowledge of epigenetic changes at RAR β2 may have implications for both cancer therapy and prevention. It is tempting to speculate that demethylating agents might have a role in cancer prevention for individuals who are at risk for cancer or for individuals in whom RAR β2 promoter methylation is detected as an early neoplastic change. Moreover, knowledge of RAR β2 methylation state in primary breast cancers may be useful to identify tumors that are more likely to respond to RA-therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor R. L. Momparler (Departement de Pharmacologie, Universite de Montreal and Centre de Recherche Pediatrique, Hopital Ste-Justine, Quebec, Canada) for suggestions and encouragement.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Qifeng Yang, Second Department of Pathology, Wakayama Medical College, 811–1 Kimiidera, Wakayama City, 641-0012 Japan. E-mail: yang-qf@mail.wakayama-med.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Evans TRJ, Kaye SB: Retinoids: present role and future potential. Br J Cancer 1999, 80:1-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hong WK, Lippman SM, Itri LM, Karp DD, Lee JS, Byers RM, Schuntz SS, Kramer AM, Lotan R, Peters LL, Dimery TW, Brown BW, Goepfert H: Prevention of second primary tumors with isotretinoin in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med 1990, 323:795-801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kraemer KH, DiGiovanna JJ, Peck GL: Chemoprevention of skin cancer in xerodermu pigmentosum. J Dermatol 1992, 19:715-718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sporn MB, Goodman DS: Chemoprevention of cancer with retinoids. Fed Proc 1979, 38:2528-2534 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lippman SM, Lee JJ, Sabichi AL: Cancer chemoprevention: progress and promise. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998, 85:1492-1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng G, Lu Y, Zlotnikov G, Thor AD, Smith HS: Loss of heterozygosity in normal tissue adjacent to breast carcinomas. Science 1996, 274:2057-2059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seewaldt VL, Johnson BS, Parker MB, Collins SJ, Swisshelm K: Expression of retinoic acid receptor beta mediates retinoic acid-induced growth arrest and apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Cell Growth Differ 1995, 6:1077-1088 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Picard E, Seguin C, Monhoven N, Rochette-Egly C, Siat Joelle, Borrelly J, Martinet Y, Martinet N, Vignaud JM: Expression of retinoid receptor genes and proteins in non-small-lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 91:1059–1066 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Xu X-C, Liu X, Tahara E, Lippman SM, Lotan R: Expression and Up-Regulation of retinoic acid receptor-β is associated with retinoid sensitivity and colony formation in esophageal cancer cell lines. Cancer Res 1999, 59:2477-2483 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu X-C, Sneige N, Liu X, Nandagiri R, Lee JJ, Lukmanji F, Hortobagyi G, Lippman SM, Dhingra K, Lotan R: Progressive decrease in nuclear retinoic acid receptor β messenger RNA level during breast carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 1997, 57:4992-4996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu Q, Li Y, Liu R, Agadir A, Lee MO, Liu Y, Zhang X: Modulation of retinoic acid sensitivity in lung cancer cells through dynamic balance of orphan receptors nur77 and COUP-TF and their heterodimerization. EMBO J 1997, 16:1656-1669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bovenzi V, Le NLO, Cote S, Sinnett D, Momparler LF, Momparler RL: DNA methylation of retinoic acid receptor β in breast cancer and possible therapeutic role of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. Anticancer Drugs 1999, 10:471-476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sirchia SM, Ferguson AT, Sironi E, Subramanyan S, Orlandi R, Sukumar S, Sacchi N: Evidence of epigenetic changes affecting the chromatin state of the retinoic acid receptor β2 promoter in breast cancer cells. Oncogene 2000, 19:1556-1563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Widschwendter M, Berger J, Hermann M, Muller HM, Amberger A, Zeschnigk M, Widschwendter A, Abendstein B, Zeimet AG, Daxenbichler G, Marth C: Methylation and silencing of the retinoic acid receptor β2 gene in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000, 92:826-832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cote S, Sinnett D, Momparler RL: Demethylation by 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine of specific 5-methylcytosine sites in the promoter region of the retinoic acid receptor β gene in human colon carcinoma cells. Anticancer Drugs 1998, 9:743-750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kane MF, Loda M, Gaida GM, Lipman J, Mishra R, Goldman H, Jessup JM, Kolodner R: Methylation of the hMLH1 promoter correlates with lack of expression of hMLH1 in sporadic colon tumors and mismatch repair-defective human tumor cell lines. Cancer Res 1997, 57:5556-5560 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sommer KM, Chen LI, Treuting PM, Smith LT, Swisshelm K: Elevated retinoic acid receptor β4 protein in human breast tumor cells with nuclear and cytoplasmic localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999, 96:8651-8656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kinzler K, Vogelstein B: Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell 1996, 87:159-170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Houle B, Rochette-Egly C, Bradley WE: Tumor-suppressive effect of the retinoic acid receptor β in human epidermoid lung cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993, 90:985-989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y, Lee MO, Wang HG, Li Y, Hashimoto Y, Klaus M, Reed JC, Zhang X: Retinoic acid receptor β mediates the growth-inhibitory effect of retinoic acid by promoting apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol 1996, 16:1138-1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berard J, Laboune F, Mukuna M, Masse S, Kothary R, Bradley WE: Lung tumors in mice expressing an antisense RARbeta2 transgene. FASEB J 1996, 10:1091-1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lotan R, Xu XC, Lippman SM, Ro JY, Lee JS, Lee JJ, Hong WK: Suppression of retinoic acid receptor β in premalignant oral lesions and its up-regulation by isotretinoin. N Engl J Med 1995, 332:1405-1410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swisshelm K, Ryan K, Lee X, Tsou HC, Beacocke M, Sager R: Down-regulation of retinoic acid receptor β in mammary carcinoma cell lies and its up-regulation in senescing normal mammary epithelial cells. Cell Growth Differ 1994, 5:133-141 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartsch D, Boye B, Baust C, zur Hausen H, Schwarz E: Retinoic acid-mediated repression of human papillomavirus 18 transcription and different ligand regulation of the retinoic acid receptor beta gene in non-tumorigenic and tumorigenic HeLa hybrid cells. EMBO J 1992, 11:2283-2291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bix M, Locksley RM: Independent and epigenetic regulation of the interleukin-4 alleles in CD4+ T cells. Science 1998, 281:1352-1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hollander GA, Zuklya S, Morel C, Mizoguchi E, Mobisson K, Simpson S, Terhorst C, Wishart W, Golan DE, Bhan AK, Burakoff SJ: Monoallelic expression of the interleukin-2 locus. Science 1998, 279:2118-2121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qiu H, Lotan R, Lippman SM, Xu X-C: Lack of correlation between expression of retinoic acid receptor-beta and loss of heterozygosity on chromosome band 3p24 in esophageal cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2000, 28:196-202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones PA, Laird PW: Cancer epigenetics comes of age. Nat Genet 1999, 21:163-167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhattacharyya N, Dey A, Minucci S, Zimmer A, John S, Hager G, Ozato K: Retinoid-induced chromatin structure alterations in the retinoic acid receptor β2 promoter. Mol Cell Biol 1997, 17:6481-6490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]