Abstract

Many of the biological changes occurring in the endometrium during the menstrual cycle bear a striking resemblance to those associated with inflammatory and reparative processes. Hence, it would not be surprising to find that cytokines known for their pro-inflammatory properties, such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), could play a key role in the physiology of this tissue and that their action would be tightly controlled by local mechanisms. In the present study, immunohistochemical and Western blot analyses show that in normal women (n = 39), the endometrial tissue expresses, in a cycle-dependent manner, the IL-1 receptor type II (IL-1RII), a molecule of which the only biological property known to date is that of capturing IL-1, inhibiting thereby its binding to the functional type I IL-1 receptor. IL-RII immunostaining was particularly intense within the lumen of the glands and at the apical side of surface epithelium. Interestingly, the intensity of staining was markedly less pronounced in the endometrium of women with endometriosis (n = 54), a disease believed to arise from the abnormal development of endometrial tissue outside the uterus, especially in the early stages of the disease (stages I and II). This study is the first to show the local expression in endometrial tissue of IL-1RII, a potent and specific down-regulator of IL-1 action and its decreased expression in women suffering from endometriosis.

Uterine endometrium, one of the most dynamic tissues of the human body, is an active site of cytokine production and action. During each menstrual cycle and throughout the reproductive phase of women’s life, the endometrial tissue undergoes a series of dynamic physiological processes of regeneration, remodeling, and differentiation, followed by necrosis and menstrual shedding at the end of the cycle should implantation not occur. It is well established that these complex events are orchestrated by the coincident variations of estrogen and progesterone levels in the peripheral circulation. However, many of the biological changes occurring in the human endometrium during the menstrual cycle bear a striking resemblance to those associated with inflammatory and reparative processes. Hence, it is not surprising to find that pro-inflammatory cytokines can be involved at autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine levels in the modulation of a variety of endometrial functions. 1,2

Interleukin-1 (IL-1) is one of the major pro-inflammatory cytokines found to act on and to be produced by endometrial tissue. 2-5 Circulating levels of IL-1 were shown to be variable during the menstrual cycle and to reach maximal levels during the secretory phase (after ovulation). 6 The cytokine is produced by trophoblastic cells, and is believed to act as an embryonic signal and to play an important role during the implantation process. 2,7,8 IL-1 is produced locally in endometrial tissue as well, mainly in the late secretory phase, 3,9 suggesting that beside its potential role in implantation and embryonic development, this cytokine may be involved in the inflammatory-like process that takes place in the endometrium at the end of each menstrual cycle.

Based on the above evidence, it is reasonable to believe that endometrial tissue possesses the appropriate regulatory mechanisms that can operate locally and maintain tight control on the local level of pro-inflammatory cytokines. This is critical for maintaining the inflammatory-like process within safe physiological limits. Any defect in such mechanisms may lead to endometrial dysfunction and consequently to endometrium-related disorders affecting the reproductive function (ie, infertility, endometriosis, dysfunctional bleeding, and neoplasia).

Little is known about the mechanisms that modulate the expression and the action of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, in the endometrium. Cell activation by IL-1 results from its binding to cell surface IL-1 receptor type-1 (IL-1RI) that in concert with IL-1 receptor accessory protein (IL-1RAcP) is capable of transducing the activation signal. 10,11 Type II IL-1 receptor (IL-1RII) has, in contrast to the type I receptor, no signaling properties, but has recently been described as a “decoy receptor.” The extracellular domain of the receptor can be shed from the cell surface as a soluble molecule that is capable of capturing IL-1, thus preventing its interaction with the functional receptor. These studies suggest that IL-1RII play an important physiological role in the regulation of IL-1 action in the inflammation sites. 12-16

In the present study, we investigated the expression of IL-1 RII in the endometria of healthy women, and women with endometriosis, a very frequent endometrium-dependent gynecological disorder. The disease is characterized by an abnormal development of endometrial tissue outside the uterus, mainly in the peritoneal cavity, and associated with an immuno-inflammatory process that has been described in the both ectopic and eutopic endometrial sites. 17-22

Our study revealed that IL-1RII is indeed expressed in endometrial tissue and in a cycle-dependent manner. The expression was omnipresent in both epithelial and stromal compartments, and was more conspicuous in the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle. The most intense immunostaining was, however, located in the luminal side of endometrial glands and surface epithelium. Interestingly, we found out that such expression was strikingly deficient in women with endometriosis, particularly in the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle.

The study provides for the first time evidence for the local expression in human endometrial tissue of the IL-1 decoy receptor, one of the most specific down-regulators of IL-1 action. Furthermore, it reveals a defect in that expression in the intrauterine endometrium of women suffering from endometriosis, that is, in the tissue where the disease is believed to take origin.

Materials and Methods

Study Participants

Women were recruited into the study after they provided informed consent for a protocol approved by the Saint-François d’Assise Hospital Ethics Committee on Human Research. Women included in the study (Table 1) ▶ had no signs of endometrial hyperplasia or neoplasia and were not receiving any anti-inflammatory or hormonal medication at least 3 months before laparoscopy. Endometriosis was diagnosed during investigative laparoscopy for infertility and/or pelvic pain, or at tubal ligation. The stage of endometriosis was determined according to the revised classification of the American Fertility Society. 23 Patients with endometriosis (n = 54) otherwise had no other pelvic pathology. Normal women (n = 39) were fertile, requesting tubal ligation, and having no visible evidence of endometriosis at laparoscopy. Menstrual cycle dating was determined by menstrual history and confirmed by histological examination using the criteria of Noyes and colleagues. 24

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients at Time of Laparoscopy

| Number of subjects | Age (Mean ± SD) | Number of subjects by cycle phase | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferative | Secretory | |||

| Controls | 39 | 35.6 ± 5.2 | 18 | 21 |

| Endometriosis (total) | 54 | 31.0 ± 5.5 | 22 | 32 |

| Stage I | 23 | 30.1 ± 6.3 | 10 | 13 |

| Stage II | 16 | 30.8 ± 4.7 | 6 | 10 |

| Stage III–IV | 15 | 32.7 ± 5.0 | 6 | 9 |

| Fertile | 24 | 30.6 ± 6.9 | 8 | 16 |

| Infertile | 30 | 31.4 ± 4.2 | 14 | 16 |

Collection of Endometrial Biopsies

Endometrial biopsies were obtained during laparoscopy with the use of a Pipelle (Unimar Inc., Prodimed, Neuilly-En-Tchelle, France). Specimens were placed at 4°C in sterile Hanks’ balanced salt solution containing 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/ml amphotericin, immediately transported to the laboratory, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen or embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Miles Inc., Elkhart, IN), and stored at −70°C until analyzed.

Immunohistochemistry

Serial 4-μm cryosections were placed on poly-l-lysine-coated glass microscope slides and fixed for 20 minutes in formaldehyde [4% in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] (Fisher Scientific, Montreal, Quebec, Canada). All incubations were performed at room temperature in a humidified chamber. Sections were rinsed in PBS, immersed in PBS-1% Triton X-100 for 20 minutes at room temperature, rinsed again in PBS, and treated for 20 minutes with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (0.3% in absolute methanol) to eliminate endogenous peroxidase. After a PBS rinse, immunostaining was performed using a mouse monoclonal anti-human IL-1RII antibody (R and D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) (primary antibody), a Vectastain Elite ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and diaminobenzidine (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) as chromogen. Briefly, after incubation with blocking serum for 30 minutes, sections were rinsed in PBS, incubated for 90 minutes with an appropriate and predetermined dilution of primary antibody (15 μg/ml of PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin), rinsed in PBS, and incubated for 60 minutes with the secondary antibody consisting of biotinylated goat anti-mouse polyclonal antibody. Sections were then rinsed in PBS and the avidin-biotinylated horseradish peroxidase complex was applied for 45 minutes. After a PBS rinse followed by a 10-minute incubation with diaminobenzidine:H2O2 (0.5 mg/0.03% H2O2 in PBS) sections were washed in tap water, counterstained with hematoxylin, and mounted with Mowiol (Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corp., La Jolla, CA). Sections incubated without the primary antibody or with nonimmune mouse serum were included as negative controls in all experiments. Slides were viewed using a Leica microscope (Leica mikroskopie und systeme GmbH, Model DMRB; Postfach, Wetzlar, Germany) and photomicrographs were taken with Kodak 100 ASA film (Kodak, Toronto, Ontario, Canada). IL-1RII immunostaining was evaluated in a blinded manner by two independent observers having no knowledge of laparoscopic findings. The intensity of staining was evaluated three times in three different areas randomly selected in the section and a mean score was given using an arbitrary scale (0, absent; 1, light; 2, moderate; and 3, intense). High concordance between the two observers was found as determined by the κ measure of agreement (κ = 0.89).

Dual Immunofluorescent Staining

Tissue sections were treated and incubated at room temperature with the mouse monoclonal anti-IL-1RII antibody as described earlier. After a PBS rinse, the sections were incubated for 60 minutes with a rabbit polyclonal anti-IL-1β antibody diluted 8:1,000 in PBS-1% bovine serum albumin (R and D Systems), washed in PBS, incubated for 60 minutes with a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Vector Laboratories) diluted 1:100 in PBS-1% bovine serum albumin, washed again in PBS, and finally incubated simultaneously for 60 minutes in the dark with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated streptavidin and a rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Sigma), which were used at a final dilution of 1:100 and 1:10 in PBS-1% bovine serum albumin, respectively. Slides were then mounted with Mowiol to which p-phenylenediamine (Sigma), an anti-fading agent, was added at a final concentration of 1 mg/ml, then observed under the Leica microscope equipped for fluorescence with a 100 watt UV lamp and photomicrographs were made with Kodak 400 ASA film. In every experiment, sections from each endometrial tissue incubated with normal mouse and normal rabbit IgGs (used at concentrations equivalent to those of the primary antibodies) were included as negative controls.

Western Blot Analysis

Frozen endometrial tissues were directly homogenized with a microscale tissue grinder (Kontes, Vineland, NJ) in a buffer containing 0.5% Triton X-100, 10 mmol/L HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 2 mmol/L ethyleneglycoltetraacetic acid, 2 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.02% NaN3, and a mix of anti-proteases composed by 5 μmol/L aprotinin, 63 μmol/L leupeptin, and 3 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Tissue homogenate was then incubated at 4°C for 45 minutes under gentle shaking, and centrifuged at 11,000 × g for 30 minutes to recover the soluble extract, whose total protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad DC Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd., Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Proteins (100 μg) from each extract were then heat-denatured in a boiling bath for 3 minutes in 5× sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer (1.25 mol/L Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 50% glycerol, 25% β-mercaptoethanol, 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 0.01% bromophenol blue), separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in 10% acrylamide linear gradient gel slabs, and transferred onto 0.45-μm nitrocellulose membranes using electrophoretic transfer cell (trans-Blot, Bio-Rad). Nitrocellulose membranes were then immersed in PBS containing 5% skimmed milk and 0.1% Tween 20 (blocking solution) for 1 hour at 37°C, cut into strips, and incubated overnight at 4°C with a monoclonal mouse anti-human IL-1RII antibody (2 μg/ml of blocking solution) (R and D Systems) or with normal mouse immunoglobulins (IgGs) of the same immunoglobulin class and concentration as the primary antibody (R and D Systems). The specificity of the immunoreaction was also verified by pre-absorption of the antibody with an excess of IL-1RII (20 μg/ml).Thereafter, the strips were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with Fc-specific peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse antibody (1:3000 dilution in the blocking solution) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA), washed three times in PBS/0.1% Tween 20, incubated with chemiluminescence reagent (Amersham, Oakville, Ontario, Canada) for 1 minute, air-dried, wrapped in a plastic bag, and exposed to a Kodak X-OMAT AR film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) for 1 minute.

Statistical Analysis

IL-1RII staining scores follow an ordinal scale. Statistical analysis was performed using Fisher’s exact test, 25 and the Bonferroni procedure was applied when more than two groups were compared. Comparison of patient’s age was performed using one-way analysis of variance. All analyses were performed using the statistical analyses system (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina). Differences were considered as statistically significant for P values <0.05.

Results

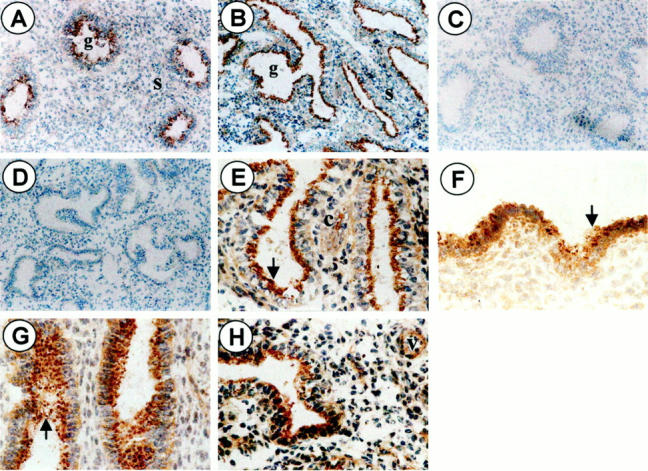

Positive immunohistochemical staining of IL-1RII was observed in many compartments of endometrial tissue. In the stroma, immunostaining was in general weak in the proliferative phase and more pronounced in the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle, mainly in isolated aggregates and microvessels (Figure 1) ▶ . However, the most marked staining was primarily located in epithelial cells. Immunostaining was observed all around cells (cellular staining), but also had the appearance of an intense brown extracellular deposit that was predominantly located within the lumen of the glands and the apical side of surface epithelium (luminal staining) (Figure 1) ▶ .

Figure 1.

Representative illustration of IL-1RII immunostaining in the human endometrium. Sections of endometrial tissue were incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-IL-1RII antibody (A, proliferative day 13; B, secretory day 24; original magnification, ×68) or with an equivalent concentration of normal mouse IgGs (C and D, respectively; original magnification, ×68). Sections were then incubated successively with biotinylated goat anti-mouse polyclonal antibody and avidin-biotinylated horseradish peroxidase complex. The immunoreaction was revealed with diaminobenzidine (brown staining) and hematoxylin was used for counterstaining (blue staining). Note the brown fine positive staining in stromal and epithelial cells (cellular staining) (E–H; original magnification, ×268), and the brown deposit (arrow) that is primarily located at the apical side of glandular (E, secretory phase day 24) and surface (F, secretory phase day 16) epithelium, or more spread within the glands lumen (G, secretory phase day 16). Positive immunostaining is also detected in isolated stromal cells (c) (G, secretory phase day 16) and microvessels (v) (H, secretory phase day 24) found in the stroma in the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle. s = stroma, g = gland.

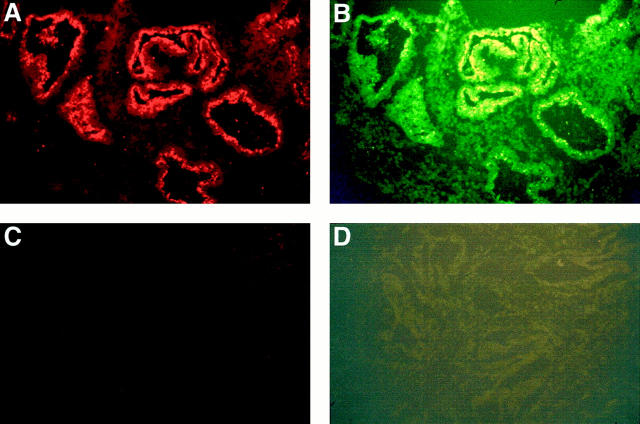

According to recent findings, IL-1RII is a decoy receptor that can be released by proteolysis from the membrane-bound receptor extracellular domain. The resulting soluble receptor seems to retain the same affinity for its natural ligand IL-1β. 12-14, 26 Dual immunofluorescence analysis using antibodies specific to IL-1RII and IL-1β clearly showed that both antigens were co-expressed within the luminal deposit that makes plausible the formation of IL-1RII-IL-1β complex (Figure 2) ▶ .

Figure 2.

Dual immunofluorescent staining of IL-1RII (A) and IL-1β (B) in the endometrial tissue of normal women. Tissue sections were successively incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-IL-1RII antibody, rabbit polyclonal anti-IL-1 antibody, and biotinylated goat anti-rabbit antibody before being incubated simultaneously with rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated streptavidin. Serial sections incubated with normal mouse and normal rabbit IgGs instead of the primary antibodies were included as negative controls (C and D) (original magnification, ×160). Note the co-expression of IL-1RII (red color) and IL-1β (green-yellow color) within the luminal deposit in endometrial glands. Data from a normal woman in the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle (day 23).

Within the same endometrial section, the intensity of staining varied without any discernible or apparent order from one gland to another. Furthermore, great variations between biopsies taken from different women at different periods of the menstrual cycle were noted. The intensity of IL-1RII cellular and luminal staining was scored in a blinded manner by two independent observers using an arbitrary scale. Statistical analysis of the data regarding the influence of the menstrual cycle using the Fisher’s exact test showed that cellular staining was effectively more intense in the secretory than in the proliferative phase of the cycle both in stromal (P = 2 × 10−5) and epithelial (P = 0.0310) cells (Table 2) ▶ . However, only a weak tendency for an increased luminal staining in glandular and surface epithelium was noted in the secretory phase of the cycle as compared to the proliferative phase (P = 0.1370) (Table 3) ▶ . Scattered brown deposits, which were encountered in the stroma, albeit less markedly than in luminal and glandular epithelium, were also more frequent in the secretory phase than in the proliferative phase, but the difference did not reach the level of statistical significance (P = 0.0930).

Table 2.

Number of Normal and Endometriosis Patients According to the Intensity of IL-1RII Cellular Immunostaining in the Stroma, and in the Glands and Surface Epithelium

| Stroma intensity of staining | P value* | Glands and surface epithelium intensity of staining | P value* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Controls | 3 | 19 | 12 | 4 | 2 | 13 | 17 | 7 | ||

| Endometriosis (total) | 5 | 25 | 22 | 0 | 0.1120 | 4 | 21 | 26 | 1 | 0.0660 |

| Stage I | 1 | 9 | 13 | 0 | 0.1750 | 3 | 7 | 13 | 0 | 0.1030 |

| Stage II | 3 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 0.3240 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 1 | 0.2580 |

| Stage III–IV | 1 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0.7120 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 0.3680 |

| Fertile | 1 | 10 | 13 | 0 | 0.1910 | 1 | 9 | 14 | 0 | 0.1280 |

| Infertile | 11 | 15 | 9 | 0 | 0.3350 | 3 | 12 | 12 | 1 | 0.3010 |

| Controls | ||||||||||

| Proliferative phase | 2 | 15 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 6 | 1 | ||

| Secretory phase | 1 | 4 | 12 | 3 | 2 ×10−5† | 0 | 4 | 11 | 6 | 0.0310† |

| Endometriosis | ||||||||||

| Proliferative phase | 4 | 14 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 14 | 4 | 0 | ||

| Secretory phase | 1 | 11 | 19 | 0 | 0.0011† | 1 | 7 | 22 | 1 | 0.0004 |

| Proliferative phase | ||||||||||

| Control | 2 | 15 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 6 | 1 | ||

| Endometriosis | 4 | 14 | 3 | 0 | 0.2430 | 3 | 14 | 4 | 0 | 0.6060 |

| Secretory phase | ||||||||||

| Control | 1 | 4 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 11 | 6 | ||

| Endometriosis | 1 | 11 | 19 | 0 | 0.0910 | 1 | 7 | 22 | 1 | 0.0530 |

*Comparison with controls, P values corrected by the Bonferroni procedure.

†Comparison of the proliferative phase with the secretory phase.

Table 3.

Number of Normal and Endometriosis Patients According to the Intensity of IL-1RII Luminal Immunostaining in the Glands and Surface Epithelium

| Glands and surface epithelium intensity of staining | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Controls | 7 | 10 | 16 | 6 | |

| Endometriosis (total) | 37 | 8 | 3 | 6 | 10−6* |

| Stage I | 17 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0.0006* |

| Stage II | 11 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0.0015* |

| Stage III–IV | 9 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.0360* |

| Fertile | 16 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0.0010* |

| Infertile | 21 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4× 10−5* |

| Controls | |||||

| Proliferative phase | 5 | 2 | 9 | 2 | |

| Secretory phase | 2 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 0.1370† |

| Endometriosis | |||||

| Proliferative phase | 13 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Secretory phase | 24 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0.0590† |

| Proliferative phase | |||||

| Control | 5 | 2 | 9 | 2 | |

| Endometriosis | 13 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0.0760 |

| Secretory phase | |||||

| Control | 2 | 8 | 7 | 4 | |

| Endometriosis | 24 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 8× 10−7* |

*Comparison with controls; only significant P values were corrected by the Bonferroni procedure.

†Comparison of the proliferative phase with the secretory phase.

Based on these findings and the recently reported down-regulatory properties of IL-1RII toward IL-1-mediated inflammation and cell activation, we further investigated whether there was any alteration in IL-1RII expression in the endometrium of women with endometriosis, a frequent endometrium-related pathology associated with an aberrant inflammatory process observed not only in ectopic sites where endometrial tissue abnormally implants, but even in the eutopic intrauterine endometrium. Endometrial biopsies were collected from 54 women presenting laparoscopical and histological evidence of endometriosis. As in normal women, cellular staining in women with endometriosis was significantly higher in the secretory phase than in the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle, both in stromal and epithelial cells (P = 0.0011 and 0.0003, respectively). However, when compared to that of normal women, this staining showed a marked trend for a decreased intensity in glandular and luminal epithelium (P = 0.0660), whereas in the stroma the difference between women with and without was less evident (P = 0.1120). Furthermore, the decreased immunostaining observed in endometrial epithelial cells of women with endometriosis compared to normal controls appeared to occur in the secretory (P = 0.0530) rather than in the proliferative (P = 0.6060) phase of the menstrual cycle (Table 2) ▶ .

Scattered brown deposits were also observed in the stroma of women with endometriosis. As in normal women, they were more obvious in the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle and showed a comparable level of staining. The most striking difference between women with endometriosis and normal women was however detected at the level of IL-1RII staining in the lumen of endometrial glands and the apical side of surface epithelium. In fact, statistical analysis of the data (Table 3) ▶ showed a considerable lack of staining in women with endometriosis compared to normal controls (P = 10−6). Endometriosis patients were then stratified by severity of disease (stage I, II, and III–IV). Comparison of individual groups using the Fisher’s exact test and the procedure of Bonferroni showed that the intensity of staining was significantly lower in each endometriosis stage compared to controls, but the most significant decrease in IL-1RII immunostaining was found in the milder stages (I and II) (P = 0.0006 and 0.0015, respectively). Furthermore, statistical analysis of the data taking into account the phase of the menstrual cycle revealed that the most marked drop in IL-1RII luminal staining in endometriosis occurred in the secretory phase (P = 8 × 10−7). This was also observed in all stages of endometriosis, but was more pronounced in the early (I and II) (P = 0.0020) than in the late stages of the disease (III–IV) (P = 0.0060). In contrast, during the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle, the difference in IL-1RII luminal immunostaining between women with and without endometriosis was perceptible, but did not reach the level of statistical significance (P = 0.0760). The 54 patients with endometriosis were also stratified for infertility and IL-1RII luminal immunostaining scores were compared. Using the Fisher’s exact test, both fertile and infertile patients with endometriosis had decreased levels of immunostaining compared with control women (P = 0.0010 and 4 × 10−5, respectively), but more significant differences in infertile women with endometriosis was noted.

Representative examples of IL-1RII immunostaining in the endometrium of women with and without endometriosis are shown in Figure 3 ▶ (A, normal secretory, day 24; B, endometriosis secretory, day 26). Note the fine brown immunostaining around cells both in the stroma and glandular epithelium, and the brown deposit in the lumen of glands in normal women. No immunoreaction was observed in negative controls in which the anti-IL-1RII antibody was replaced by an equal concentration of mouse immunoglobulins of the same isotype or pre-absorbed with an excess of IL-1RII before incubation with endometrial tissue sections (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Representative illustration of IL-1RII immunostaining in the endometrium of women with and without endometriosis. A: Normal secretory day 24, luminal staining score 3, cellular staining score 2 in stromal and epithelial cells. B: Endometriosis stage secretory day 26, luminal staining score 0, cellular staining score 2 in stromal and epithelial cells. Note the lack of staining within the lumen of endometrial glands in B. Original magnification, ×160.

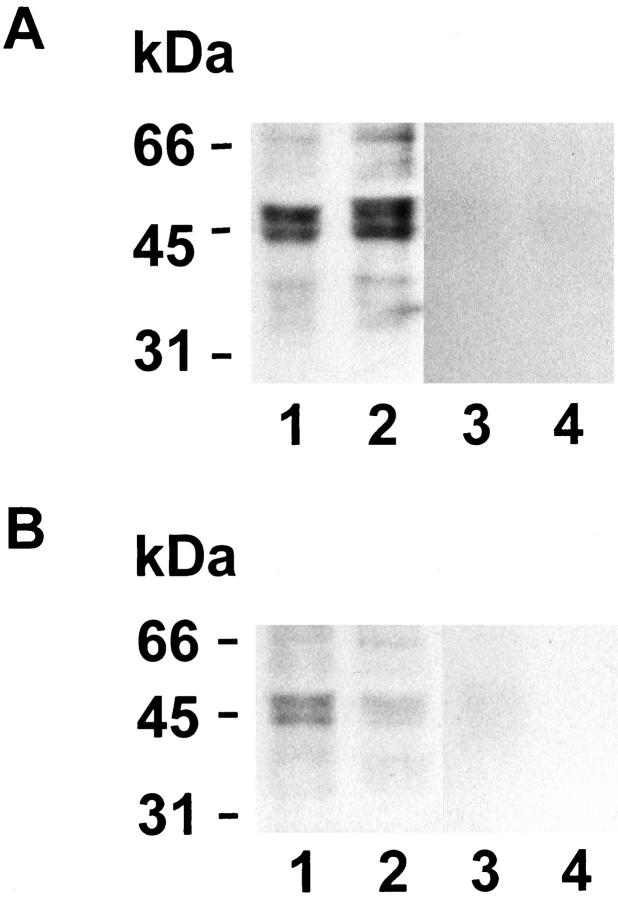

To confirm immunohistochemical data regarding the expression of IL-1RII in normal and endometriosis women and to determine whether the mobility of the endometrial receptor corresponds to the known molecular weight of this protein, equivalent amounts of endometrial proteins were analyzed by Western blot. Endometrial biopsies were selected from the proliferative and the secretory phases.

Figure 4 ▶ shows that monoclonal anti-IL-1RII antibody reacted primarily with a 68-kd band and a doublet of 45- and 48-kd molecular weight bands. Sixty-eight and 45 kd correspond to the reported molecular weights of the membrane-bound and the soluble forms of the IL-1RII receptor, respectively. 11-13 Minor bands of lower molecular weights recognized specifically by the antibody have not been reported previously and may presumably correspond to degradation products. However, for the same amount of total endometrial proteins, the intensity of IL-1RII bands was clearly lower in biopsies from women with endometriosis included within the same experiments.

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis of IL-1RII expression in the endometrial tissue. A: Normal women: day 10 (lanes 1 and 3) and day 24 (lanes 2 and 4). B: Women with endometriosis: stage II, day 13 (lanes 1 and 3) and stage II, day 25 (lanes 2 and 4). Equal amounts of endometrial proteins (100 μg/lane) were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. IL-1RII was detected using a mouse monoclonal antibody (lanes 1 and 2) and the immunocomplex was revealed by chemiluminescence. No immunoreaction was observed in negative controls where the anti-IL-1RII antibody was replaced by an equal concentration of mouse immunoglobulins of the same isotype (lanes 3 and 4).

Discussion

In the present study, we have shown that IL-1RII expression was ubiquitous throughout the endometrial tissue, and was in general cycle phase-dependent. The most marked immunostaining, which appeared microscopically as an extracellular brown deposit, was observed in the gland’s lumen and the apical side of luminal epithelium. The luminal secretion most likely corresponds to the soluble form of IL-1RII. Western blot analysis of IL-1RII in endometrial biopsies have shown, in fact, the presence of bands whose molecular weights are equivalent to those reported for the membrane-bound (68 kd) and the soluble (45 kd) forms of the IL-1RII receptor. Numerous recent studies have reported that IL-1RII is a decoy receptor that could be released in a soluble form after enzymatic cleavage of the extracellular domain of the membrane-bound receptor. The soluble receptor possesses the ability to bind IL-1β, the circulating and most active form of IL-1, inhibiting thereby the interaction of the latter with the functional IL-1RI and, consequently, IL-1-mediated cell activation. 12-14,26 Dual immunofluorescence analysis showed that IL-1RII and IL-1β were both effectively co-expressed within the luminal deposit, which makes plausible the formation of IL-1RII-IL-1β complex. These findings might be of interesting physiological significance. In fact IL-1 is one of the major cytokines that are involved in the different cyclic events occurring in human endometrium. 1,2 The cytokine has been demonstrated as a key mediator in the attachment of the embryo onto the endometrium and the implantation process. 2,7,8 In the peripheral circulation, IL-1 levels increase after ovulation, 6 and, locally within endometrial tissue, IL-1 production has been shown to considerably increase in the secretory phase, reaching its maximal levels at the end of the menstrual cycle. 9 Hence the considerable importance of the local availability in the endometrium of a regulatory mechanism such as that of IL-1RII that can counterbalance or buffer the local action of IL-1 and maintain its levels within the physiological limits during the crucial period of implantation and during the inflammatory-like process that takes place in the endometrium at the end of each menstrual cycle.

To investigate the role of IL-1RII in endometrium-related disorders, we assessed its expression in the endometrium of women suffering from endometriosis. The disease is associated with an immuno-inflammatory process observed consistently in the peritoneal cavity where endometrial tissue abnormally develops, 9,17,27 and recently noticed in the eutopic intrauterine endometrium of patients as well. 21,28,29 According to our data, the eutopic endometrium of women with endometriosis expresses in situ increased levels of MCP-1, 22 a chemokine endowed with the potent ability of inducing monocyte/macrophage chemoattraction and activation. 30 Furthermore, cultured endometrial epithelial cells from women with endometriosis displayed an increased responsiveness to IL-1 in vitro by secreting higher amounts of MCP-1 than cells from normal women after exposure to the same concentrations of the proinflammatory cytokine. 31 However, the cause(s) of such an exaggerated inflammatory reaction remain unknown. The present study shows a dramatic lack in IL-1RII expression in endometrial tissue of women with endometriosis. This was particularly obvious at the level of IL-1RII luminal secretion, but was also noticeable at the level of the cellular expression both in epithelial and stromal cells. Western blot analysis of IL-1RII expression in endometrial tissue confirmed immunohistochemical data as it showed that the intensity of the 68-kd and lower molecular weight bands recognized specifically by the anti-IL-1RII antibody, was markedly lower in women with endometriosis as compared to normal controls.

The most striking lack in IL-1RII luminal expression was observed in the earliest and initial stages of the disease (stages I and II). On one hand, this in keeping with numerous studies indicating that endometriosis is more active in the initial stages 32-34 and is consistent with the pattern of MCP-1 expression that we observed in the endometrium of endometriosis patients that increased in initial and decreased in late endometriosis stages. 22 On the other hand, these results suggest that abnormal IL-IRII expression may be involved in the initiation of the inflammatory process in the intrauterine endometrial tissue where the disease is believed to take origin. Interestingly, our study also showed that defective IL-1RII expression was more significant in infertile than in fertile women having endometriosis, which suggests an involvement in endometriosis-associated infertility.

The mechanisms underlying the decreased expression of IL-1RII in women with endometriosis remain to be further elucidated. The most significant deficiency occurred at the level of IL-1RII luminal secretion in epithelial cells, in particular in the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle. This would suggest an inhibited shedding of the receptor in endometriosis occurring throughout the cycle, but to a greater extent in the second phase. At the present time, it is still unclear what molecular and biochemical pathways could be involved in the generation of soluble IL-RII. According to recent data, matrix metalloproteases rather than differential splicing, play a key role in the production of soluble decoy RII by enzymatic cleavage from the cell surface receptor. 15 The observation of higher levels of cellular staining in epithelial cells of women with endometriosis in the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle as compared to the proliferative phase (P = 0.00037, Table 2 ▶ ), makes plausible a potential inhibition of IL-1RII release from the cell surface in the secretory phase. However, our results also show that either cellular staining in epithelial cells or the intensity of the 68-kd band corresponding to the reported membrane-bound form of IL-1RII receptor was reduced in women with endometriosis. This suggests that beyond a potential aberrant release of sIL-1RII from endometrial cells of women with endometriosis, a deficiency in IL-1RII protein synthesis and/or a reduced IL-1RII mRNA levels or gene transcription might be involved. In fact, our preliminary analyses of IL-1RII mRNA levels in the endometria of women with and without endometriosis tend to support such a hypothesis (data not shown).

In conclusion, this is the first study to show the expression in endometrial tissue of the decoy IL-1 receptor type II, a specific natural inhibitor of IL-1 that plays an important role in the regulation of IL-1β activity in the uterine environment. Furthermore, our study revealed a striking lack in IL-1RII expression in women suffering from endometriosis. This may represent a plausible mechanism underlying immuno-inflammatory changes observed in the eutopic endometrium of women with endometriosis as well as in endometrial tissue abnormally implanted in ectopic sites.

Acknowledgments

We thank the group of investigation in gynecology (Drs. François Belhumeur, Jacques Bergeron, Jean Blanchet, Marc Bureau, Simon Carrier, Elphège Cyr, Marlène Daris, Jean-Louis Dubé, Jean-Yves Fontaine, Céline Huot, Pierre Huot, Johanne Hurtubise, Philippe Laberge, André Lemay, Rodolphe Maheux, Jacques Mailloux, Antonin Rochette, and Marc Villeneuve) for patient evaluation and providing endometrial biopsies; and Madeleine Desaulniers, Isabelle Paradis, Monique Longpré, and Johanne Pelletier for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Ali Akoum, Ph.D., Laboratoire d’Endocrinologie de la Reproduction, Centre de Recherche, Hôpital Saint-François d’Assise, 10 rue de l’Espinay, Local D0-711, Québec, Québec, Canada, G1L 3L5. E-mail: ali.akoum@crsfa.ulaval.ca.

Supported by grant MT-14638 from the Medical Research Council of Canada (to A. A.). A. A. is a Chercheur-Boursier Senior of the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec (FRSQ).

References

- 1.Tabibzadeh S: Human endometrium: an active site of cytokine production and action. Endocr Rev 1991, 12:272-290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon C, Moreno C, Remohi J, Pellicer A: Cytokines and embryo implantation. J Reprod Immunol 1998, 39:117-131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon C, Piquette GN, Frances A, Polan ML: Localization of interleukin-1 type I receptor and interleukin-1 beta in human endometrium throughout the menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1993, 77:549-555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon C, Valbuena D, Krussel J, Bernal A, Murphy CR, Shaw T, Pellicer A, Polan ML: Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist prevents embryonic implantation by a direct effect on the endometrial epithelium. Fertil Steril 1998, 70:896-906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabibzadeh S, Kaffka KL, Satyaswaroop PG, Kilian PL: Interleukin-1 (IL-1) regulation of human endometrial function: presence of IL-1 receptor correlates with IL-1-stimulated prostaglandin E2 production. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1990, 70:1000-1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cannon JG, Dinarello CA: Increased plasma interleukin-1 activity in women after ovulation. Science 1985, 227:1247-1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Psychoyos A: The implantation window: basic and clinical aspects. Front Endocrinol 1993, 4:57-63 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheth KV, Roca GL, Al-Sedairy ST, Parhar RS, Hamilton CJ, Al-Abdul Jabbar F: Prediction of successful embryo implantation by measuring interleukin-1-alpha and immunosuppressive factor(s) in preimplantation embryo culture fluid. Fertil Steril 1991, 55:952-957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kauma S, Matt D, Strom S, Eierman D, Turner T: Interleukin-1 beta, human leukocyte antigen HLA-DR alpha, and transforming growth factor-beta expression in endometrium, placenta, and placental membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990, 163:1430-1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dinarello CA: Biologic basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood 1996, 87:2095-2147 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boraschi D, Bossù P, Macchia G, Ruggiero P, Tagliabue A: Structures-function relationship in the IL-1 family. Front Sciences 1995, 1:270-308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colotta F, Re F, Muzio M, Bertini R, Polentarutti N, Sironi N: Interleukin-1 type II receptor: a decoy target for IL-1 that is regulated by IL-4. Science 1993, 261:472-475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colotta F, Dower SK, Sims JE, Mantovani A: The type II ‘decoy’ receptor: a novel regulatory pathway for interleukin 1. Immunol Today 1994, 15:562-566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bossù P, Visconti U, Ruggiero P, Macchia G, Muda M, Bertini R, Bizzarri C, Colagrande A, Sabbatini V, Maurizi G, Del Grosso E, Tagliabue A, Boraschi D: Transfected type II interleukin-1 receptor impairs responsiveness of human keratinocytes to interleukin-1. Am J Pathol 1995, 147:1852-1861 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orlando S, Sironi M, Bianchi G, Drummond AH, Boraschi D: Role of metalloproteases in the release of the IL-1 type II decoy receptor. J Biol Chem 1997, 50:31764-31769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coulter KR, Wewers MD, Lowe MP, Knoell DL: Extracellular regulation of interleukin (IL)-1beta through lung epithelial cells and defective IL-1 type II receptor expression. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1999, 20:964-975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Witz CA, Schenken RS: Pathogenesis of endometriosis. Semin Reprod Endocrinol 1997, 15:199-208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McMaster MT, Lim KH, Taylor RN: Immunobiology of human pregnancy. Curr Probl Obstet Gynecol Fertil 1998, 21:5-23 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oral E, Olive DL, Arici A: The peritoneal environment in endometriosis. Hum Reprod Update 1996, 2:385-398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ota H, Igarashi S, Hayakawa M, Matsui T, Tanaka H, Tanaka T: Effect of danazol on the immunocompetent cells in the eutopic endometrium in patients with endometriosis: a multicenter cooperative study. Fertil Steril 1996, 65:545-551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tseng JF, Ryan IP, Milam TD, Murai JT, Scheriock ED, Landers DV, Taylor RN: Interleukin-6 secretion in vitro is up-regulated in ectopic and eutopic endometrial stromal cells from women with endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996, 81:1118-1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jolicoeur C, Boutouil M, Drouin R, Paradis I, Lemay A, Akoum A: Increased expression of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 in the endometrium of women with endometriosis. Am J Pathol 1998, 152:125-133 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.: American Fertility Society: Revised American Fertility Society classification of endometriosis. Fertil Steril 1985, 43:351-352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noyes RW, Hertig Rock J: Dating the endometrial biopsy. Fertil Steril 1995, 1:3-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siegel S, Castellan NJ: Nonparametric Statistics for the Behaviour of Science, ed 2 1988, McGraw-Hill, New York

- 26.Symons JA, Young PR, Duff GW: Soluble type II interleukin 1 (IL-1) receptor binds and blocks processing of IL-1β precursor and loses affinity for IL-1 receptor antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995, 92:1714-1718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vinatier D, Dufour P, Oosterlynck D: Immunological aspects of endometriosis. Hum Reprod Update 1996, 2:2371-2384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Isaacson KB, Galman M, Coutifaris C, Lyttle CR: Endometrial synthesis and secretion of complement component-3 by patients with and without endometriosis. Fertil Steril 1990, 53:836-841 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vigano P, Gaffuri B, Somigliana E, Busacca M, Di Blasio AM, Vignali M: Expression of intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 mRNA and protein is enhanced in endometriosis versus endometrial stromal cells in culture. Mol Hum Reprod 1998, 4:1150-1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leonard EJ, Yoshimura T: Human monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1). Immunol Today 1990, 11:97-101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akoum A, Lemay A, Brunet C, Hébert J, : Le Groupe d’Investigation en Gynécologie: Secretion of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 by cytokine-stimulated endometrial cells of women with endometriosis. Fertil Steril 1995, 63:322-328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haney AF, Jenkins S, Weinberg JB: The stimulus responsible for the peritoneal fluid inflammation observed in infertile women with endometriosis. Fertil Steril 1991, 56:408-413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vernon MW, Beard JS, Graves K, Wilson EA: Classification of endometriotic implants by morphologic appearance and capacity to synthesize prostaglandins. Fertil Steril 1986, 46:801-806 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lessey B, Castelbaum AJ, Sawin SW: Aberrant integrin expression in the endometrium of women with endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1994, 79:643-649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]