Abstract

We addressed the effect of angiopoietin expression on tumor growth and metastasis. Overexpression of angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2) in Lewis lung carcinoma and TA3 mammary carcinoma cells inhibited their ability to form metastatic tumors and prolonged the survival of mice injected with the corresponding transfectants. In contrast, angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1) overexpression had no detectable effect on the ability of either tumor type to disseminate. Tumors derived from Ang-2-overexpressing cells displayed aberrant angiogenic vessels that took the form of vascular cords or aggregated vascular endothelial cells with few associated smooth muscle cells. These vascular cords or aggregates were accompanied by endothelial and tumor cell apoptosis, suggesting that an imbalance in Ang-2 expression with respect to Ang-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor may disrupt angiogenesis and tumor survival in vivo. Our observations suggest that Ang-2 may play an important role in regulating tumor angiogenesis.

Regulation of tissue perfusion is accomplished by two major mechanisms depending on the type of demand. The requirement for a rapid increase or reduction in blood flow is met by local vascular dilation or constriction, whereas the long-term regulation of blood supply relies on new blood vessel outgrowth or vascular regression. In the adult, physiological angiogenesis is limited to female reproductive organs, during the menstrual cycle and pregnancy, and to tissue repair. In pathological conditions, angiogenesis plays a key role in the regulation of inflammation and in the survival and growth of both primary and metastatic cancer. 1 Angiogenesis is defined as the sprouting of blood vessels from pre-existing ones and begins by focal reduction of vascular intercellular interactions and interactions between vascular cells and the extracellular matrix (ECM). These changes are illustrated by the loosening or loss of endothelial cell interactions with pericytes and smooth muscle cells, leading to the loss of vascular integrity, and are followed by endothelial cell proliferation, invasion, and remodeling of the ECM. 2,3 Reorganization of the ECM is thought to facilitate the formation of a new endothelial cell network that evolves into functional blood vessels that mature on deposition of basal lamina and recruitment and association of pericytes and/or smooth muscle cells on the abluminal endothelial cell surface.

Numerous classes of molecules are implicated in regulating angiogenesis, including growth factors and their receptors, a variety of proteases, adhesion receptors, and ECM components. 4-6 Key endothelial cell-specific growth factor receptors include the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors 1 (Flt1) 7,8 and 2 (Flk1) 9 and the Tie receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK), Tie-1 and Tie-2. 10-15 Tie-2, which is expressed in the normal vasculature 16 and is up-regulated in tumor angiogenic vessels, 17,18 has at least two known ligands, angiopoietin (Ang)-1 and -2. 15,19,20 Stimulation of Flk1 and Flt1 by VEGF, respectively, promotes endothelial cell migration/proliferation and tube formation. 21-23 Engagement of Tie-2 by Ang-1 promotes recruitment of pericytes and smooth muscle cells, thereby helping to establish and maintain vascular integrity and quiescence, induces endothelial sprouting in vitro, 24 and stimulates endothelial cell migration in culture. 25 Ang-2 is an antagonist of Ang-1, that competes for Tie-2, and induces the loosening of the interactions between endothelial and perivascular support cells and ECM, reducing vascular integrity and facilitating access to angiogenic inducers. 26

Angiogenesis is dependent on a tightly regulated balance between angiogenic promoters and inhibitors, 4 and it is becoming apparent that the production of VEGFs and angiopoietins must be coordinated both quantitatively and temporally to ensure appropriate angiogenesis. 26 Thus, Ang-2-dependent loosening of endothelial cell interactions with support cells and ECM, that precedes vessel sprouting, requires the cooperation of VEGF that is thought to supply endothelial cells with critical survival signals that may, in part, substitute for those provided by cell-cell and cell-ECM interaction. 18,27 In the absence of VEGF and/or Ang-1, Ang-2 production may cause irreversible loss of vascular structures, which, in the physiological situation, such as the menstrual cycle, corresponds to vascular involution.

Ang-1 and -2 are soluble 70-kd factors, which consist of an amino-terminal coiled-coil domain and a carboxy-terminal fibrinogen-like domain. 19,20 Targeted disruption of Ang-1 and overexpression of Ang-2 both resulted in embryonic death with defects in the normal angiogenesis. 15,20 Recent evidence indicates that both factors are expressed in tumor vasculature, 18,27 but the role of angiopoietins in tumor angiogenesis remains to be determined. To directly address the effect of angiopoietins in tumor angiogenesis, we overexpressed Ang-2 and Ang-1 in Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) and TA3 mammary carcinoma cells and tested the ability of the transfectants to form local and metastatic tumors in syngeneic mice. Our results indicate that overexpression of Ang-2, but not Ang-1, in both LLC and TA3 cells inhibits their tumor forming properties in both subcutaneous growth and experimental metastasis assays. Tumors derived from cells overexpressing Ang-2 exhibited aberrant angiogenesis in vivo, characterized by disorganized aggregates of endothelial cells with few or no associated smooth muscle cells, and massive apoptosis of endothelial cells and surrounding tumor cells. These observations provide evidence that Ang-2 may play a regulatory role in tumor angiogenesis and suggest that its potential use toward therapeutic ends may justify further studies.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Antibodies

LLC (ATCC, Rockville, MD) and TA3 mammary carcinoma 28 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA). All LLC and TA3 transfectants were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 5 mg/ml blasticidin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Anti-vWF, anti-smooth muscle actin, anti-CD34 mAb, anti-VEGF, and anti-v5 epitope tag antibodies were from DAKO (Carpinteria, CA), Pharmingen La Jolla, (CA), Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY), and Invitrogen, respectively. The Apoptag kit was purchased from Oncor, Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD).

Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) and Expression Constructs

Total RNA was isolated from mouse placenta, B16F1 and B16 F10 melanoma cells, and LLC and TA3 carcinoma cells using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. cDNA was synthesized from 5 mg of total RNA using Superscript II RNase H− reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Inc.). PCR was performed as described 28 using the following primer pairs: Ang-1: forward, 5′-ATCTACACTATTTATTTTAATAAT-3′; reverse, 5′-AAAGTCCAAGGGCCGGATCATCAT-3′; Ang-2: forward, 5′-GAGGGAGGACTGGTGACAGCCACGG-3′; reverse, 5′-GAAATCTGCTGGCCGGATCATCAT-3′; VEGF: forward, 5′-ACCATGAACTTTCTGCTCTCTTGG-3′; reverse, 5′-CCGCCTTGGCTTGTCACATCTGCA-3′.

Full-length Ang-1 and Ang-2 cDNAs were isolated by PCR from mouse placenta cDNA using Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and primer pairs corresponding to the 5′- and 3′-most 24 nucleotides of the coding sequence of each molecule derived from GenBank accession numbers U83509 and AF004326. The stop codons were omitted from the reverse primers to ensure C-terminal v5 epitope tag for both Ang-1 and Ang-2 molecules. The resulting PCR fragments were inserted into pEF6/V5-His TOPO vector (Invitrogen), which contains an C-terminal v5-epitope tag and a blasticidine resistance gene (Invitrogen). Authenticity and correct orientation of the Ang-1 and Ang-2 inserts were confirmed by DNA sequencing using the dideoxy chain termination method.

Transfection

LLC and TA3 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine (Life Technologies, Inc.) with expression vectors containing cDNAs encoding Ang-1, Ang-2, or with expression vector alone. Stable transfectants were selected for growth in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and blasticidine (5 μg/ml), and resistant colonies were picked after 2to 3 weeks of growth in the selection medium. The culture supernatants of the transfectants were tested by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and Western blot analysis using anti-v5 mAb (Invitrogen) for expression of the appropriate gene products.

Sample Preparation and Western Blot Analysis

Serum-free supernatants of cultured LLC and TA3 transfectants were collected, concentrated using Amicon filters (Millipore, Bedford, MA), and separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The proteins were transferred onto Hybond-ECL membranes (Amersham Corp., Arlington Heights, IL) and v5-tagged Ang-1 and Ang-2 were detected using anti-v5 mAb (Invitrogen).

Tumor Growth and Metastasis

Transfected LLC and TA3 cells (10 6 in 0.2 ml of Hanks’ balanced salt solution per mouse) were injected subcutaneously or intravenously into male syngeneic C57BL or A/Jax mice, respectively (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). Three independent isolates of each transfectant were used. Six mice were injected for each transfectant and two independent experiments were performed, such that each transfectant was injected into a total of 12 mice. The animals were observed daily. The duration of survival of the mice injected intravenously was monitored, and animals that seemed to be symptom-free 3 months after injection were sacrificed and examined at autopsy for detectable tumor growth. The lungs from all intravenously injected mice were removed and fixed for histological analysis. Mice were sacrificed 4 weeks after subcutaneous injection, and the tumors were isolated, weighed, and sectioned to assess angiogenesis.

Histology and Immunocytochemistry

Solid tumors from the experimental animals and lungs derived from intravenously injected mice were dissected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), washed with PBS, dehydrated through 30%, 70%, 95%, and 100% ethanol and xylene, and embedded in paraffin wax (Fisher). Five- to 10-mm sections were cut, mounted onto slides, and stained with either Gill-2 hematoxylin and eosin (Fisher) for histological analysis, anti-von Willebrand factor, anti-smooth muscle actin, anti-CD34, and anti-VEGF antibodies (DAKO, Pharmingen, and Upstate) to assess tumor angiogenesis, or Apoptag (Oncor, Inc.) to assess apoptosis.

Results

Ang-2 Is Expressed by Tumor Cells

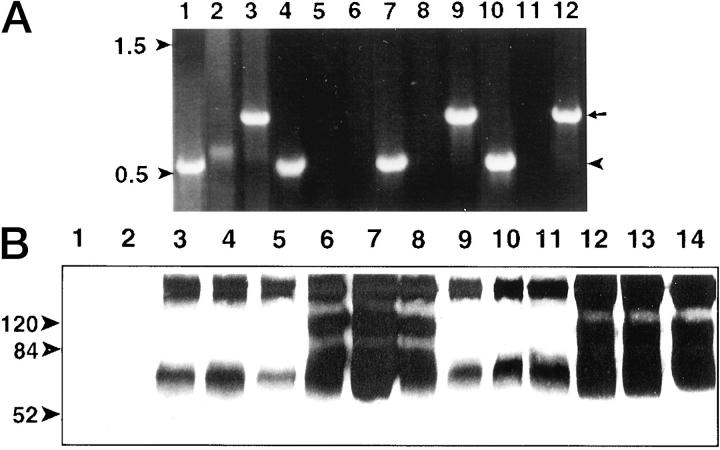

Unlike its more widely expressed antagonist, Ang-1, Ang-2 expression is thought to be primarily confined to endothelial cells. 20,25 Because malignant cells frequently generate their own angiogenesis regulating factors, we addressed angiopoietin expression in B16F1 and F10 melanoma, and LLC and TA3 mammary carcinoma cells by RT-PCR analysis. Ang-2 transcripts were readily detected in LLC, B16F1, and F10 melanoma cells (Figure 1A ▶ ; lanes 3, 9, 12, arrow), but not in TA3 cells (Figure 1A ▶ , lane 6). Ang-1 was only weakly expressed by LLC cells as assessed by RT-PCR (Figure 1A ▶ , lane 2). By contrast, VEGF was expressed in all four tumor cell lines (Figure 1A ▶ ; lanes 1, 4, 7, 10).

Figure 1.

Expression of Ang-1 and Ang-2 in tumor cell lines and transfectants. A: RT-PCR of transcripts from LLC (lanes 1–3), TA3 mammary carcinoma (lanes 4–6), B16F1 melanoma (lanes 7–9), and B16F10 melanoma (lanes 10–12) cells. VEGF (lanes 1, 4, 7, 10; arrowhead on right), Ang-1 (lanes 2, 5, 8, 11), and Ang-2 (lanes 3, 6, 9, 12; arrow on right) transcripts are shown. Arrowheads on left indicate the migration of 500- and 1500-bp molecular markers. B: Expression of Ang-1-v5 and Ang-2-v5 in serum-free conditioned media of LLC and TA3 cell transfectants as detected by Western blot analysis using anti-v5 antibody. Conditioned media were from: lanes 1 and 2, LLC and TA3 cells, respectively, transfected with vector only; lanes 3–8, independent isolates of LLC cells transfected with Ang-1-v5 (lanes 3–5) and Ang-2-v5 (lanes 6–8); lanes 9–14, independent isolates of TA3 cells transfected with Ang-1-v5 (lanes 9–11) and Ang-2-v5 (lanes 12–14). Molecular weight markers are indicated.

The finding that Ang-2 is expressed by several tumor cell lines led us to address the possible role of Ang-2 in tumor angiogenesis. Full-length mouse Ang-1 and Ang-2 cDNAs were isolated from mouse placenta mRNA by RT-PCR, inserted into v5-his-tagged expression vectors (pEF/V5-His TOPO) and verified for identity, appropriate orientation, and absence of mutations by dideoxy sequence analysis. Each cDNA expression vector was then stably transfected into LLC and TA3 cells. Transfectants were selected for blasticidin resistance and tested for Ang-1 and Ang-2 production by Western blot analysis of the corresponding conditioned serum-free culture media using anti-v5 mAb. Substantial variability in Ang-1 and Ang-2 production by the different transfectants was observed (Figure 1B ▶ and data not shown). Monomeric Ang-1 and Ang-2 are ∼70 kd (Figure 1B) ▶ , and as reported, have a tendency to form aggregates (Figure 1B) ▶ . Multiple independent transfectants were selected for subsequent experiments to minimize the possibility of observing behavior that reflects peculiarities of individual clones. Comparison for growth rate in vitro failed to show any effect of either Ang-1 or Ang-2 overexpression on LLC or TA3 cell proliferation (data not shown).

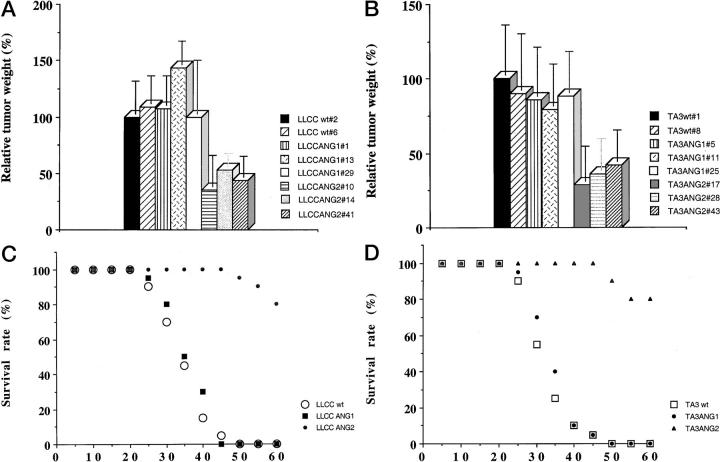

Ang-2 Expression by LLC and TA3 Tumor Cells Inhibits Local Tumor Growth

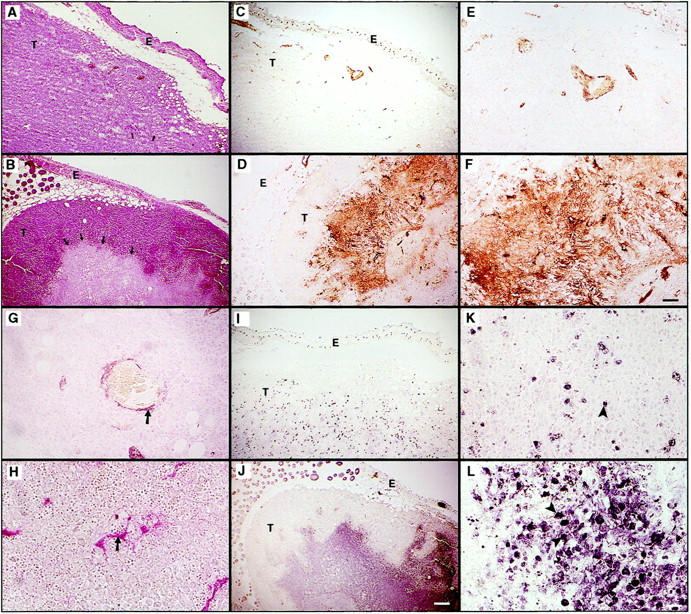

LLC and TA3 transfectants expressing Ang-1 or Ang-2 were injected subcutaneously into syngeneic mice and tumor development was compared to that derived from cells transfected with the expression vector alone. Three independent isolates of each transfectant were used for each experiment, and two independent experiments were performed. In each experiment six syngeneic mice were injected with each transfectant, such that a total of 36 mice were used to assess the effect of each angiopoietin in each cell type. Ang-1 expression did not significantly alter the rate of growth of either LLC- or TA3-derived tumors (Figure 2, A and B) ▶ . However, expression of Ang-2 in both cell types resulted in marked reduction of tumor growth (Figure 2, A and B) ▶ . The observed reduction in tumor growth varied according to the level of Ang-2 expression, and transfectants with the highest expression formed tumor nodules of 1 to 3 mm that failed to grow to a larger size even after several weeks (data not shown). In the cases illustrated in Figure 2 ▶ , mock-, Ang-1- and Ang-2-transfectant tumors were palpable 2 weeks after injection, but whereas mock transfectants formed rapidly growing tumors from that point on, Ang-2 transfectants displayed consistently slower growth. Thus, the difference in tumor size shown does not reflect delayed onset but rather slower and more limited growth. Histologically, these tumors displayed several distinct features. First, viable tumor tissue was found in a peripheral cuff, whereas the center appeared pale, consistent with necrotic and/or apoptotic tissue, and contained multiple hemorrhagic areas. By contrast, tumors derived from Ang-1 and vector-only transfectants seemed more homogeneous (Figure 3, A and B) ▶ . Second, whereas Ang-1 and vector-only transfectant-derived tumors displayed well-defined blood vessels surrounded by smooth muscle cells (Figure 3 ▶ ; C, E, and G, and data not shown), the central areas of Ang-2 transfectant-derived tumors stained positive for von Willebrand factor (vWF) and CD34, both of which are endothelial cell markers, with CD34 being more restricted to endothelium of angiogenic vessels, but the vessels appeared as cord-like structures with rare or absent lumina (Figure 3, D and F ▶ , and data not shown), and few disorganized smooth muscle cells (Figure 3H) ▶ . No detectable difference in VEGF expression was observed among Ang-2 and Ang-1 overexpressing and parental tumors (data not shown). Massive apoptosis of vascular endothelial cells and surrounding tumor cells, as indicated by terminal dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining, was observed within the Ang-2 transfectant-derived tumor centers (Figure 3, J and L) ▶ . In contrast, the LLC carcinoma cells transfected with Ang-1 and expression vector showed a low percentage of apoptotic cells that were evenly distributed within the solid tumor (Figure 3, I and K ▶ , and data not shown).

Figure 2.

LLC and TA3 tumor growth and dissemination in syngeneic mice. Transfected LLC and TA3 cells (10 6 in 0.2 ml of Hanks’ balanced salt solution per mouse) were injected subcutaneously or intravenously into male syngeneic C57BL or A/Jax mice, respectively (Jackson Laboratory). Three independent isolates of each transfectant were used and at least 12 mice were injected with each transfectant. The animals were observed daily and were sacrificed 4 weeks after subcutaneous injection, whereupon tumors were isolated and weighed. The relative tumor weights are shown in A and B. The data are calculated by comparing the mean weight of transfectant-derived tumors with that of tumors derived from one isolate of LLC or TA3 cells transfected with expression vector alone, which is arbitrarily assigned a 100% value. Each bar represents the mean weight ± SD of tumors from 12 mice injected with the corresponding LLC or TA3 cell transfectant. The duration of survival of the mice injected intravenously was monitored and shown in C and D for animals injected with LLC and TA3 transfectants, respectively. Survival curves for a total of 36 mice injected with each type of transfectant (vector alone, Ang-1- and Ang-2-transfected LLC, or TA3 cells) are shown.

Figure 3.

Histology of subcutaneous LLC tumors derived from cells transfected with vector only (A, C, E, G, I, K) and Ang-2 cDNA (B, D, F, H, J, L). Sections were stained with H&E (A and B), anti-vWF antibody (C–F), anti-smooth muscle actin mAb (G and H), and assessed by TUNEL assay (I–L). Arrows in B indicate the demarcation between the peripheral cuff of viable tumor cells and the central area containing necrotic and apoptotic cells. Around the central area of the Ang-2-expressing tumor there are numerous structures that stain positively with anti-vWF antibody (D and F). Unlike the well-formed vessels in tumors derived from vector-only transfected cells (C and E), Ang-2-expressing tumor vasculature displays small or absent lumina and cord-like structure. Similarly, smooth muscle cells that surround vessels in tumors from vector-transfected LLC (G, arrow) are scattered haphazardly in Ang-2-overexpressing tumors (H, arrow). Whereas vector-transfected tumors display few scattered apoptotic cells (I and K, arrowheads), the central areas of Ang-2-overexpressing tumors have massive apoptotic cell death (J and L, arrowheads). E, epidermis; T, tumor. Scale bars: 200 μm (A–D, I, and J), 100 μm (E and F), and 50 μm (G, H, K, and L).

Ang-2 Expression Blocks Tumor Metastasis and Results in Aberrant Tumor Angiogenesis and Tumor Cell Apoptosis

As in the above experiments, a total of 36 mice were injected intravenously with three independent isolates of each angiopoietin transfectant (12 mice per isolate per cell type). Both TA3 and LLC cells form lung tumor nodules when injected into the tail vein of syngeneic mice, and death because of tumor growth typically occurred within 4 to 6 weeks after injection of 1 × 10 6 tumor cells. Ang-1 overexpression neither hindered nor promoted TA3 and LLC tumor formation in the lungs and did not affect animal survival (Figure 2, C and D ▶ , and data not shown). However, Ang-2 expression reduced and even abrogated tumor nodule formation in the lungs by both types of cells, and most of the animals survived to the end of the study period (Figure 2, C and D) ▶ . Gross examination of lung tissue at autopsy revealed no apparent tumor nodules (data not shown).

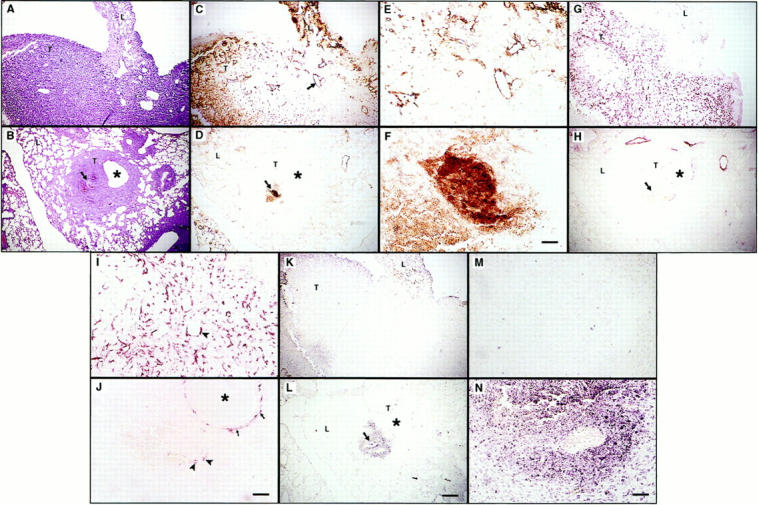

Histological examination of lung tissue sections from animals injected with LLC carcinoma cells expressing Ang-1 or vector only, revealed large confluent tumor nodules that invaded most of the lung parenchyma (Figure 4A) ▶ . Histological examination of lungs from animals injected with LLC carcinoma cells expressing Ang-2, on the other hand, revealed either absence of detectable tumor tissue (in 50% of mice) or between one and 10 microscopic tumor nodules that were typically centered by bronchioles or pre-existing peribronchial blood vessels (Figure 4B) ▶ . Remarkably, and in contrast to Ang-1 and vector transfectant-derived tumors, the majority of angiogenic vessels within these small tumor nodules, as identified by anti-vWF and anti-CD34 antibody staining, displayed an aberrant structure, characterized by aggregates of endothelial cells, with a narrow or absent lumen (Figure 4, C–F ▶ , and data not shown). A notable feature was the paucity or absence of smooth muscle cells surrounding the endothelial cells, in contrast to the normal angiogenic vessels in tumors derived from Ang-1 and vector-only transfected cells (Figure 4, G–J ▶ , and data not shown). TUNEL staining revealed that both endothelial and surrounding tumor cells were undergoing apoptosis in the Ang-2-expressing tumors whereas only occasional scattered TUNEL-positive cells were observed in tumors derived from Ang-1 and vector-only transfected cells (Figure 4, K–M ▶ , and data not shown).

Figure 4.

Histology of lung tumors derived from intravenously injected LLC transfected with vector only (A, C, E, G, I, K, M), or Ang-2 cDNA (B, D, F, H, J, L, N). Sections were stained with H&E (A and B), anti-vWF (C–F), and anti-smooth muscle actin mAb (G–J), and assessed by TUNEL assay (K–N). Serial sections are shown. Ang-2-transfected LLC cells formed small tumors surrounding bronchioles (B, D, H, L; asterisks indicate the lumina of bronchioles) with few vascular structures (B and D, arrows). These structures appeared abnormal compared to the vasculature of tumors derived from vector-only transfected cells (C, arrow, and E), and were surrounded by few if any smooth muscle cells (H, arrow; J, arrowhead). In contrast, smooth muscle cells appeared to be abundant around bronchioles of the host lung (J, arrows) and around vessels in the vector-only transfectant-derived tumors (G and I, arrowhead). Whereas tumor nodules derived from vector-only transfected cells displayed few apoptotic cells, as assessed by TUNEL analysis (K and M), endothelial as well as tumor cell apoptosis was observed around the aberrant vascular structures in nodules derived from Ang-2-transfected cells (L and N, arrow). L, host lung tissues; T, tumor nodules. Scales bars: 200 μm (A–D, G, H, K, and L), 100 μm (E, I, and J), 50 μm (F, M, and N).

Discussion

The temporal and quantitative balance in the expression of angiogenic factors seems to be key in the regulation of physiological as well as tumor angiogenesis. The observations presented here indicate that an imbalance between VEGF, Ang-1, and Ang-2, created by tumor cell overexpression of Ang-2, can lead to the disruption of tumor angiogenesis resulting not only in the reduction of local tumor growth but in the inhibition of tumor formation in experimental metastasis assays. In contrast, overexpression of Ang-1 did not seem to modify the rate of local or metastatic growth of either tumor type. The salient histological feature of Ang-2 secreting tumors was aberrant and incomplete angiogenesis, consistent with the notion that Ang-2 inhibits Ang-1-dependent vascular maturation. Tumor nodules that developed from Ang-2-secreting cells in experimental metastasis assays, seemed to do so by co-opting pre-existing blood vessels and were localized exclusively in peribronchial areas. These nodules were typically microscopic and displayed both vascular endothelial and tumor cell apoptosis. Most of the apoptotic cell death in the tumors was observed around the aberrant angiogenic vessels, consistent with the notion that the vessels are unable to provide appropriate nutritive support to the tumor tissue.

Earlier studies had suggested a possible association between high levels of Ang-2 expression, in the absence of VEGF, and tumor cell death. 18,27 In rat gliomas, Ang-2, VEGF, and Tie-2 expression were observed to vary in location and magnitude as a function of tumor size. In small tumors, Ang-2 transcripts were consistently observed in the vessels whereas VEGF expression was minimal. Tie expression was up-regulated in larger tumors, whereas VEGF induction was observed only in very large tumors and appeared in tumor cuffs surrounding the peripheral vessels, 27 where it coincided with Ang-2 expression. Areas where massive tumor cell apoptosis occurred were associated with Ang-2 expression in the absence of VEGF. In a separate study, Ang-2 expression was observed in endothelial cells of a subset of glioblastoma blood vessels that were typically associated with few periendothelial support cells. 18 Our present observations provide strong functional support for these correlations and indicate that disrupting the balance between VEGF (found to be expressed at comparable levels in vector-only, Ang-1, and Ang-2 transfectants), Ang-1 and Ang-2 by tumor cell overexpression of Ang-2 has a potent inhibitory effect on tumor growth and dissemination.

The mechanism of Ang-2-associated endothelial cell death remains to be elucidated, but the absence of smooth muscle cells, that normally associate with endothelial cells to form mature vascular structures may provide an important lead. The inability of the endothelial cells to recruit smooth muscle cells may on the one hand lead to the absence of fully formed blood vessels, resulting in leakage and/or hemorrhage, and on the other, induce endothelial cell apoptosis because of the lack of signals generated by the physical interaction between smooth muscle and endothelial cells that ensure endothelial survival. 29 In addition, recent observations suggest that Tie-2 receptor engagement by Ang-1 may induce survival signals in vascular endothelial cells by activating the phosphatidyl 3′-inositol kinase/Akt signal transduction pathway. 30,31 It seems reasonable to predict that absence of Tie-2-mediated Akt activation coupled to ineffective interaction with smooth muscle cells, is responsible, at least in part, for the observed endothelial cell apoptosis.

The observed effect of Ang-2 on tumor growth seems to be the result of its interaction with endothelial cell receptors. We have not observed Ang-2 interaction with the tumor cell surface (data not shown) rendering unlikely the possibility that Ang-2 might have a direct effect on tumor survival and growth by engaging tumor cell surface receptors other than Tie-2. This notion is supported by the observation that expression of Ang-2 failed to alter tumor cell growth in vitro. Furthermore, histological examination of lung tissue at early time points in animals injected with Ang-2 overexpressing tumor cells, revealed focal host vascular endothelial apoptosis and hemorrhage (data not shown), consistent with the possibility that tumor-derived Ang-2 may trigger pre-existing vascular endothelial cell death. Taken together, our results provide evidence that Ang-2 overexpression in tumor cells inhibits tumor angiogenesis and may induce apoptosis of host endothelial cells to which tumor cells adhere. The hypoxia and lack of nutrients that accompany these effects may explain the extensive apoptosis observed in Ang-2 overexpressing tumors as well as the microscopic nature of tumor nodules in the lungs of animals injected with Ang-2 transfectants.

The present work extends previous observations by others that Ang-2 expression correlates with vascular regression and provides functional evidence that overexpression of Ang-2 has an anti-angiogenic effect in tumors. 18,27 The observation that Ang-2 can effectively block disseminated tumor growth raises the possibility that it may have a role to play in therapeutic anti-angiogenic intervention. Thus far, multiple synthetic reagents and ECM degradation products have been shown to have anti-angiogenic action, 32 but their therapeutic value remains to be fully elucidated. Creating an imbalance among angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors by targeting Ang-2 or synthetic Ang-2 mimetics that bind Tie-2 and displace Ang-1, to the tumor vasculature, may provide a means to control local and disseminated tumor growth. Such an approach offers the advantage of modulating the activity of a naturally occurring receptor whose physiological function is precisely the regulation of angiogenesis.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Ivan Stamenkovic, M.D., Massachusetts General Hospital. Molecular Pathology Unit, 149 13th Street-7th Floor, Charlestown, MA 02129-2000. E-mail: stamenko@helix.mgh.harvard.edu.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA55735 and GM54176.

References

- 1.Folkman J: Angiogenesis in cancer, vascular, rheumatoid and other disease. Nat Med 1995, 1:27-31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingber DE, Folkman J: How does extracellular matrix control capillary morphogenesis? Cell 1989, 58:803-805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Risau W: Differentiation of endothelium. FASEB J 1995, 9:926-933 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanahan D, Folkman J: Patterns and emerging mechanism of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell 1996, 86:353-364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Risau W: Mechanism of angiogenesis. Nature 1997, 387:671-674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gale NW, Yancopoulos GD: Growth factors acting via endothelial cell-specific receptor tyrosine kinases: VEGFs, angiopoietins, and ephrins in vascular development. Genes Dev 1999, 13:1055-1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mustonen T, Alitalo K: Endothelial receptor tyrosine kinases involved in angiogenesis. J Cell Biol 1999, 129:895-898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fong GH, Rossant J, Gertenstein M, Breitman ML: Role of the Flt-1 receptor tyrosine kinase in regulating assembly of vascular endothelium. Nature 1995, 376:66-70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shalaby F, Rossant J, Yamaguchi TP, Gertsenstein M, Wu XF, Breitman ML, Schuh AC: Failure of blood-island formation and vasculogenesis in Flk-1-deficient mice. Nature 1995, 376:62-66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dumont DJ, Yamaguchi TP, Conlon RA, Rossant J, Breitman ML: Tek, a novel tyrosine kinase gene located on mouse chromosome 4, is expressed in epithelial cells, and their presumptive precursors. Oncogene 1992, 7:1471-1480 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato TN, Qin Y, Kozak CA, Audus KL: Tie-1 and tie-2 define a new class of putative receptor tyrosine kinase genes expressed in early embryonic vascular system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993, 90:9355-9358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnurch H, Risau W: Expression of tie-2, a member of a novel family of receptor tyrosine kinases, in the endothelial cell lineage. Development 1993, 119:957-968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dumont DJ, Grawohl G, Fong GH, Puri MC, Gertsenstein M, Auerbach A, Breitman ML: Dominant-negative and targeted null mutations in the endothelial receptor tyrosine kinase, tek, reveal a critical role in vasculogenesis of the embryo. Genes Dev 1994, 8:1897-1909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sato TN, Tozawa Y, Deutsch U, Wolburg-Buchholz K, Fujiwara Y, Gendron-Magurire M, Gridley T, Wolbrug H, Risau W, Qin Y: Distinct roles of the receptor tyrosine kinase Tie-1 and Tie-2 in blood vessel formation. Nature 1995, 376:70-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suri C, Jones PF, Patan S, Bartunkova S, Maisonpierre PC, Davis S, Sato TN, Yancopoulos GD: Requisite role of angiopoietin-1, a ligand for the tie2 receptor, during embryonic angiogenesis. Cell 1996, 87:1171-1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong AL, Haroon ZA, Werner S, Dewhirst MW, Greenberg CS, Peters KG: Tie2 expression, and phosphorylation in angiogenic, and quiescent adult tissues. Circ Res 1997, 81:567-574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters KG, Coogan A, Berry D, Marks J, Iglehart JD, Kontos CD, Rao P, Sankar S, Trogan E: Expression of Tie2/Tek in breast tumor vasculature provides a new marker for evaluation of tumor angiogenesis. Br J Cancer 1998, 77:51-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stratmann A, Risau W, Plate KH: Cell-type specific expression of angiopoietin-1 and angiopoietin-2 suggests a role in glioblastoma angiogenesis. Am J Pathol 1998, 153:1459-1466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis S, Aldrich TH, Jones PF, Acheson A, Compton DL, Jain V, Ryan TE, Bruno J, Radziejewski C, Maisonpierre P, Yancopoulos GD: Isolation of angiopoietin-1, a ligand for the tie2 receptor, by secretion-trap expression cloning. Cell 1996, 87:1161-1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maisonpierre PC, Suri C, Jones PF, Bartunkova S, Wiegand SJ, Radziejewski C, Compton D, McClain J, Aldrich TH, Papadopoulos N, Daly TJ, Davis S, Sato TN, Yancopoulos GD: Angiopoietin-2, a natural antagonist for Tie 2 that disrupts in vivo angiogenesis. Science 1999, 277:55-60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leung DW, Cachianes G, Kuang WJ, Goeddel DV, Ferrara N: Vascular endothelial growth factor is a secreted angiogenic mitogen. Science 1989, 246:1306-1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plouet J, Schilling J, Gospodarowicz D: Isolation and characterization of a new identified endothelial cell mitogen produced by AtT20 cells. EMBO J 1989, 8:3801-3806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrara N, Carver-Moore K, Chen H, Dowd M, Lu L, O’Shea KS, Powell-Braxton L, Hillan KJ, Moore MW: Heterozygous embryonic lethality induced by targeted inactivation of the VEGF gene. Nature 1996, 380:439-442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koblizek TL, Weiss C, Yancopoulos GD, Deutsch U, Risau W: Angiopoietin-1 induces sprouting angiogenesis in vitro. Curr Biol 1998, 8:529-532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Witzenbichler B, Maisonpierre PC, Jones P, Yancopoulos GD, Isner JM: Chemotactic properties of angiopoietin-1 and -2, ligands for the endothelial-specific receptor tyrosine kinase Tie 2. J Biol Chem 1998, 273:18514-18521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lauren J, Gunji Y, Alitalo K: Is angiopoietin-2 necessary for the initiation of tumor angiogenesis? Am J Path 1998, 153:1333-1339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holash J, Maisonpierre PC, Compton D, Boland P, Alexander CR, Zagzag D, Yancopoulos GD, Weigand SJ: Vessel cooption, regression, and growth in tumors mediated by angiopoietins and VEGF. Science 1999, 284:1994-1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu Q, Toole BP, Stamenkovic I: Induction of apoptosis of metastatic mammary carcinoma cells in vivo by disruption of tumor cell surface CD44 function. J Exp Med 1997, 186:1985-1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shepro D, Morel NML: Pericyte physiology. FASEB J 1993, 7:1031-1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papapetropoulos A, Fulton D, Mahboubi K, Kalb RG, O’Connor DS, Li F, Altieri DC, Sessa WC: Angiopoietin-1 inhibits endothelial cell apoptosis via Akt/Survivin pathway. J Biol Chem 2000, 275:9102-9105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim I, Kim HG, So JN, Kim JH, Kwak HJ, Koh GY: Angiopoietin-1 regulates endothelial cell survival through the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase/Akt signal transduction pathway. Circ Res 2000, 86:24-29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sage EH: Pieces of eight: bioactive fragments of extracellular proteins as regulator of angiogenesis. Trends Cell Biol 1997, 7:182-186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]