Abstract

This study reports the presence of oval-shaped pores in the basement membrane of the human bronchial airway that may be used as conduits for immune cells to traffic between the epithelial and mesenchymal compartments. Human bronchial mucosa collected after surgery was stripped of epithelial cells without damaging the basement membrane. Both scanning and transmission electron microscopy showed oval-shaped pores 0.75 to 3.85 μm in diameter in the bronchial basement membrane at a density of 863 pores/mm2. Transmission electron microscopy showed that the pores spanned the full depth of the basement membrane, with a concentration of collagen-like fibers at the lateral edges of the pore. Infiltrating cells apparently moved through the pores, both in the presence and absence of the epithelium. Taken together, these results suggest that immune cells use basement membrane pores as predefined routes to move between the epithelial and mesenchymal compartments without disruption of the basement membrane. As a persistent feature of the basement membrane, pores could facilitate inflammatory cell access to the epithelium and greatly increase the frequency of intercellular contact between trafficking cells.

In the airway, the epithelial basement membrane provides both the substrate for the epithelium and the boundary that strictly separates the epithelial and mesenchymal compartments. Epithelial and mesenchymal cells do not cross this boundary except under pathological conditions, such as full thickness damage to the epithelium or invasive tumorigenesis. In contrast, cells of the immune system move extensively between and within the epithelial and subepithelial compartments. The bronchial basement membrane can therefore be considered as a selective boundary for the passage of cells between the epithelial and mesenchymal compartments.

The recruitment of immune cells to mucosal sites is highly regulated, and the subsets of immune cells that enter the epithelium play a key role in immune surveillance and local mucosal immune responses. Neutrophils and eosinophils traverse the basement membrane and the epithelial compartment predominantly in a basal-to-apical direction, accumulating in the airway lumen, as evidenced by their presence in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. 1-3 In contrast, intraepithelial T lymphocytes and dendritic antigen-presenting cells (APCs) cross the epithelial basement membrane in both basal-to-apical and apical-to-basal directions. 4,5 Although the basal and columnar cells that make up the bronchial epithelium do not pass through the basement membrane, they will readily migrate across it to cover areas of damage. 6

As well as providing structural support, the basement membrane can facilitate adhesion and migration of epithelial cells through interaction with extracellular matrix proteins. 7 The basement membrane is also required for the establishment of the correct epithelial polarity and can modulate the phenotype of epithelial cells. 8,9 The upper basement membrane layers, the lamina lucida (which is considered an artifact of current preparatory techniques), and the lamina densa are synthesized predominantly by epithelial cells, whereas the lower, thicker lamina reticularis is of fibroblastic origin. 10-12 The combination of the lamina lucida and lamina densa forms the basal lamina. All layers comprise collagens, glycoproteins, and proteoglycans, although the composition varies between layers. 13

Conventionally, infiltrating immune cells are thought to cross the basement membrane by localized digestion. This would be facilitated by the release of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), particularly the gelatinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 and stored granule proteases. 14-17 However, in intestinal and conjunctival epithelia, holes in the basement membrane, termed pores, have been identified, indicating an alternative mechanism for the migration of cells into and out of the epithelium. 18-20 Furthermore, a recent report by Evans and colleagues using rat tracheal preparations has described “openings” in the lamina reticularis layer of the basement membrane. 21

The identification of basement membrane pores in conducting airways in this study provides a novel model for improving our understanding of cell trafficking between the epithelium and the underlying mesenchyme. Basement membrane pores would allow enhanced movement between epithelial and mesenchymal compartments without enzymatic disruption of the basement membrane and could facilitate interaction between inflammatory cells.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection

Rings of primary or lobar bronchus were excised from grossly normal areas of bronchial tissue after lung cancer resection and stored in Leibowitz (L15) medium (Gibco, Paisley, UK) at 4°C overnight.

A total of 10 samples underwent the epithelial stripping procedure, following a method modified for bronchial tissue from Mahida et al. 19 Tissue was washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove excess mucus, and the unstripped samples were fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 mol/L cacodylate/0.23 mol/L sucrose buffer for a minimum of 1 hour for electron microscopy. Samples for stripping were first incubated in 10 mmol/L dithiothreitol (DTT; Sigma, Poole, UK) in PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature. Following this, tissue was incubated in Ca2+/Mg2+-free Hanks’ balanced salt solution (Gibco) for 10 minutes at 37°C and then 10 mmol/L ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA; Sigma) in PBS for 30 minutes at 37°C. This was repeated twice, before culture or fixation in 3% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 mol/L cacodylate/0.23 mol/L sucrose buffer. For three samples, the technique was further modified by using a 13-mm round glass coverslip to gently stroke the airway surface at the end of each 30-minute incubation. Eight samples stripped of epithelium were cultured in M199 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 2% Ultroser G serum replacement (Gibco) for a maximum of 48 hours.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (EM) Preparation

Fixed tissue was transferred to 0.1 mol/L cacodylate/0.23 mol/L sucrose buffer and dehydrated through a graded series of alcohols. The tissue underwent critical point drying with CO2 using a Balzers critical point drier (Balzers, Liechtenstein). Dried specimens were glued onto metal stubs and sputter-coated with a platinum/gold mixture. Scanning EM was performed on a Hitachi S800 (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) scanning electron microscope. Representative micrographs were taken of each sample.

Transmission EM Preparation

Fixed tissue was transferred to 0.1 mol/L cacodylate/0.23 mol/L sucrose buffer before 2 hours postfixation in 2% osmium tetroxide in cacodylate/sucrose buffer. The tissue was then incubated in 1.5% aqueous uranyl acetate for 30 minutes at room temperature before dehydration through a series of graded alcohols and embedding in Spurr resin, following a standard protocol. A suitable area of epithelium in transverse section was selected and ultrathin sections were cut using a diamond knife on an Ultracut ultramicrotome (Leica, Milton Keynes, UK) set to 90 nm. Sections were dried onto copper grids, stained with lead citrate, and examined on a Hitachi H7000 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi). The full length of the basement membrane of each section was scanned for pores, and all pores were photographed.

Pore Counts and Analysis

Three scanning EM photographs (×500 magnification) were taken of stripped basement membrane from each sample. Pores were counted and the area of stripped basement membrane measured by image analysis (Scion Image PC, Scion Corp., Frederick, MD). Pore counts were represented as pores/mm 2 of basement membrane. The minimum and maximum diameter of each pore was determined using a magnifying eyepiece with a 20-mm scale bar and converted back to original size.

Nearest neighbor distances were calculated by measuring the distance between each individual pore and its five nearest neighbors. After ranking the results in order of distance, Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics were applied to test for differences in the spatial arrangement of the pores from a normal distribution, using the SPSS statistical program v.9 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Morphology of the Bronchial Epithelial Basement Membrane

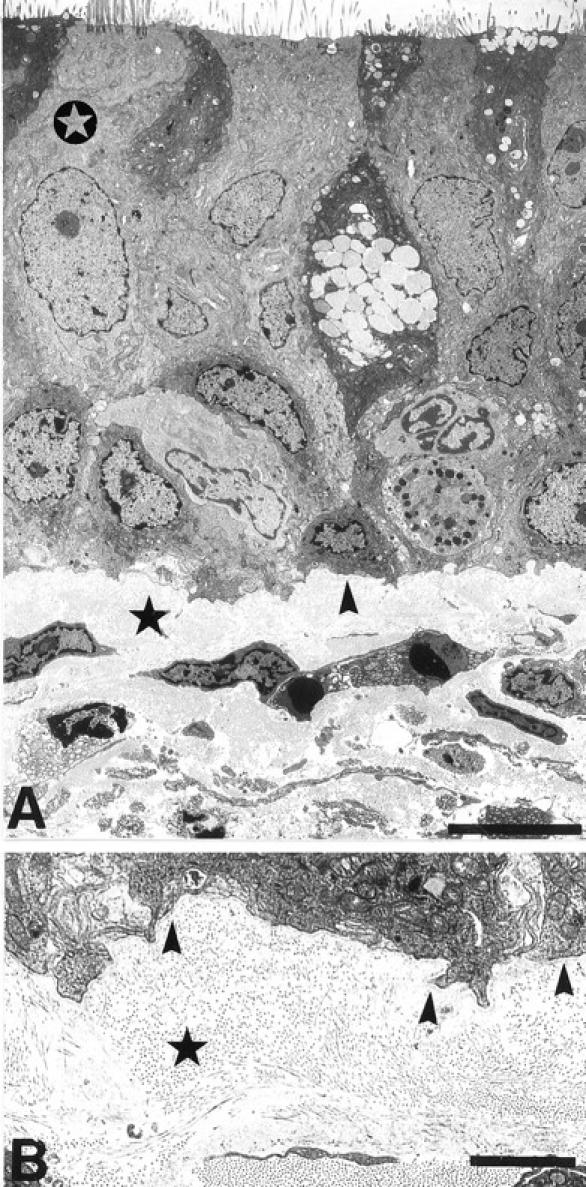

Transmission EM of undamaged bronchial epithelium revealed basal cells attached to the basement membrane and ciliated columnar cells and nonciliated secretory cells suprabasal to these (Figure 1A) ▶ . The complete basement membrane consisted of the lamina densa, a thin afibrous and agranular layer, whereas the lamina reticularis extended below contained fibrous collagen cut in mostly transverse section (Figure 1B) ▶ . A boundary was evident between the acellular lamina reticularis and the cellular lamina propria, which included infiltrating cells (Figure 1A) ▶ .

Figure 1.

Transmission electron micrographs of normal human bronchial epithelium. A: The pseudostratified structure of the bronchial epithelium with upper ciliated cells (open star), resting on a layer of basal cells attached to the upper basement membrane layer of lamina densa (arrowhead). The underlying cellular lamina propria is separated from the lamina densa by the lamina reticularis (star). B: Higher magnification of the lamina densa and overlying basal cell showing the lamina densa as an afibrous layer (arrowheads), whereas fibrous collagen was found in the lamina reticularis cut in mostly transverse section (star). Scale bars, 5 μm (A) and 2 μm (B).

Basement Membrane Pores

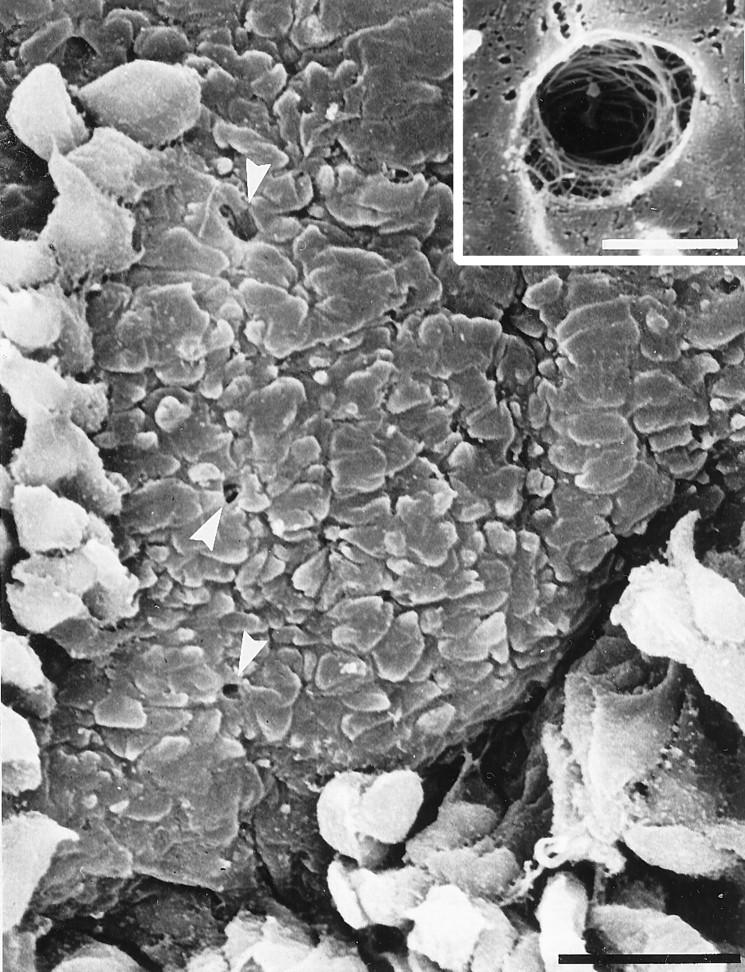

The basement membrane had a complex topography with an undulating structure of ridges and grooves a few micrometers across. Holes in the basement membrane were seen, clearly distinct from these ridges and grooves (Figure 2) ▶ . These were approximately oval, larger than the ridges, and were seen by scanning EM to penetrate into the basement membrane. The junction between the surface of the basement membrane and the internal structure of the pore was clearly delineated, and a collagen-like fibrous network lining the pore was revealed at higher magnifications (Figure 2 ▶ , inset). Although identification of the fibers was not possible by scanning EM, they appeared to surround the cylindrical pore in concentric rings. Pores were subsequently identified as oval holes with clear penetration of the basement membrane.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of an untreated bronchial epithelial sample, illustrating a limited area of damage to the epithelium to the level of the basement membrane caused by nonchemical means. Some columnar and basal cells remain attached in surrounding areas. Pores are found as oval structures distinct from the nodular basement membrane (arrowheads). Inset: Higher magnification view of a basement membrane pore showing the concentric rings of fibers lining the pore. Scale bar, 20 μm (2 μm in inset).

Pores were also clearly evident by transmission EM spanning the basal lamina and lamina reticularis to a depth of 2 to 5 μm and terminating at the intersection with the lamina propria (Figure 3A) ▶ . Transmission EM revealed fibers surrounding both edges of the pore, spanning the full width of the basement membrane; the fibers being characteristic of collagen cut predominantly in transverse section (Figure 3B) ▶ . Furthermore, at the intersection between the pore and lamina propria, channels could be seen leading up to the pore with cells present within these channels (Figure 3A) ▶ .

Figure 3.

Transmission electron micrograph of bronchial epithelial basement membrane with a pore in longitudinal section. A: The pore (arrowheads) traverses the full thickness of the basement membrane with epithelium (E) intact and connects with what appears to be a cell-filled channel at the lamina reticularis/lamina propria boundary (star). LR, lamina reticularis. B: Higher magnification of the lateral edges of the pore. The lamina densa (arrowheads) ends at the lip of the pore and the lateral edges of the pore appear lined with collagen-like fibrils. Scale bars, 5 μm (A) and 1 μm (B).

Epithelial Stripping Procedure

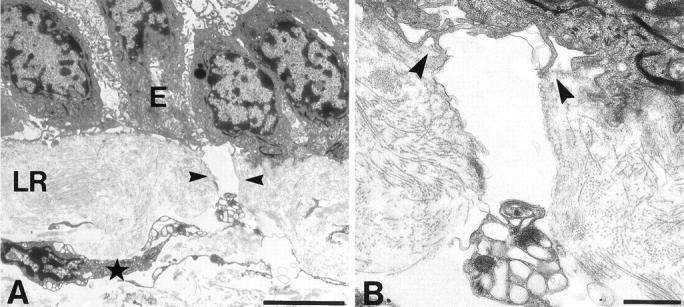

To study the basement membrane pores effectively, a stripping procedure using DTT and EDTA to chelate Ca2+ and break disulfide bonds, adapted from the method of Mahida et al, was used to remove covering epithelial cells from the basement membrane. 19 Low-magnification scanning EM examination of samples stripped in this manner showed patchy loss of the epithelium; in some areas, columnar but not basal cells were lost, and in others, the epithelium was removed to the level of the basement membrane. As this technique did not yield extensive areas of denuded basement membrane, further mechanical removal of epithelial cells was facilitated by using a circular glass coverslip. After this procedure, all samples showed extensive loss of basal and columnar cells, with epithelial cells remaining only in the deeper crevices of the epithelium. Scanning EM of basement membrane after stripping using a coverslip (Figure 4) ▶ was indistinguishable from unstripped basement membrane samples after unintentional loss of epithelial cells (Figure 2) ▶ . Moreover, by light microscopy of sections, neither sample showed any differences in the overall morphology of the basement membrane or lamina propria after DTT or EDTA treatment (results not shown).

Figure 4.

Scanning electron micrograph of bronchial basement membrane denuded of epithelium following a stripping procedure involving coverslip scraping. No columnar or basal cells remain attached to the basement membrane and the basement membrane retains its nodular appearance without apparent damage. Basement membrane pores are clearly evident (arrowheads). Scale bar, 20 μm.

Characteristics of Basement Membrane Pores

Three scanning EM micrographs of stripped samples at the same magnification were analyzed for each of 10 different individuals. The mean pore count was 863 pores/mm 2 (range, 208-2337; SD = 404 pores/mm2) with 95% confidence limits of 718-1009 pores/mm2, indicating that the variation in pore density between samples was low. Measurement of pore diameters showed that the mean diameter of the pore was 1.76 μm (range, 0.6–3.85 μm; SD = 0.67 μm). Variation in pore size was also low, with 95% confidence limits of 1.70–1.81 μm for the overall mean pore size. Pore diameter from transmission EM sections revealed a similar width distribution, with a mean pore diameter of 2.08 μm and a range of 0.62 to 4.2 μm. The mean distance between a pore and its nearest neighbor was 12.8 μm (range, 4.0–31.8 μm; SD = 5.25 μm). No significant difference was found on comparison of distribution of nearest neighbor measurements with a normal distribution.

Functional Use of Basement Membrane Pores

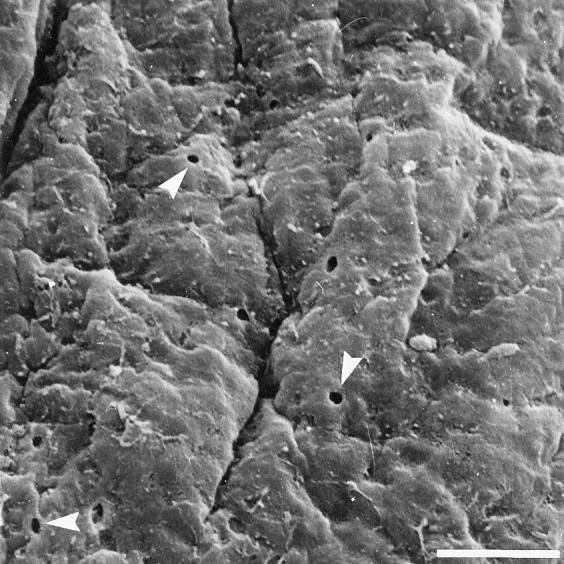

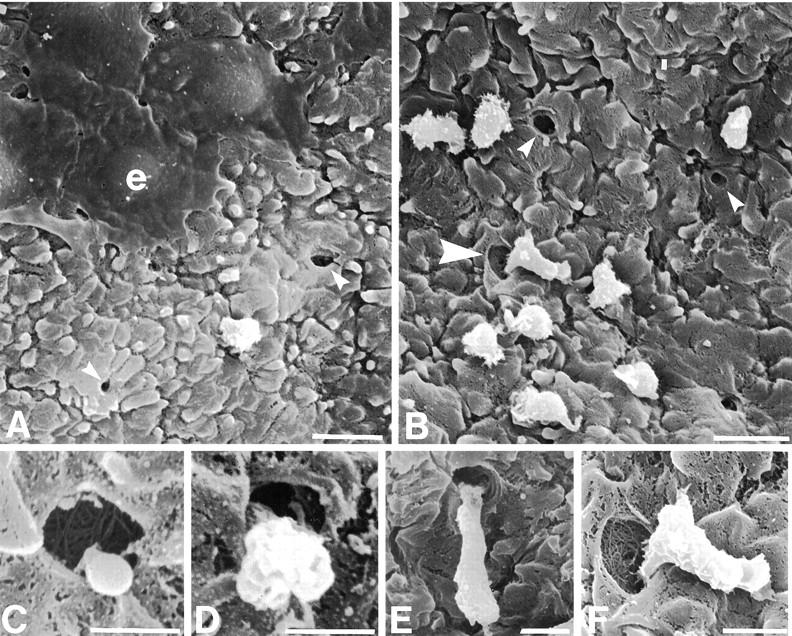

Epithelial cells remaining on the basement membrane after culture exhibited a flattened morphology with the features of the basement membrane visible below the cells, which was consistent with a dedifferentiated epithelium performing epithelial restitution (Figure 5A) ▶ . This contrasted with the rounded appearance of nonepithelial cells after the same length of culture (Figure 5, A and B) ▶ .

Figure 5.

Scanning electron micrograph of bronchial epithelial basement membrane after 24 hours’ culture. A: Epithelial cells (e) display a flattened morphology consistent with their migration across a denuded basement membrane, a nonepithelial cell with contrasting morphology is located between two pores (small arrowheads). B: Cells of nonepithelial morphology located on the basement membrane near pores (small arrowheads), with one cell apparently exiting a pore (large arrowhead). C–F: Morphology of cells consistent with different stages of cell migration through basement membrane pores. C: A cytoplasmic process appears to extrude from the lumen of a pore. D: A pore is blocked by the main body of a cell. E and F: The majority of a cell rests on the basement membrane surface adjacent to a pore, whereas cell processes clearly extend into the pore (F, magnified image of B). Scale bars, 10 μm (A and B), 2 μm (C and D), and 4 μm (E and F).

In all cultured samples, nonepithelial cells were seen on the epithelial side of the basement membrane, localized close to pores (Figure 5, A and B) ▶ . Although it is impossible to define movement in electron micrographs, cells could be observed extruding partly or wholly through the lumen of the pore. Occasional cells were seen with cytoplasmic extensions into the pore, consistent with cell migration through the pore (Figure 5, C–F) ▶ . The configuration of the cell processes suggested that they had not formed the pore.

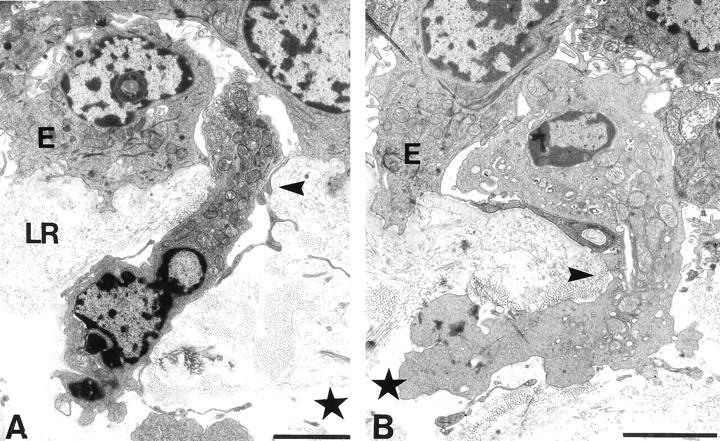

This pattern of cells traversing the basement membrane through basement membrane pores occurred not only in samples where the epithelium had been removed, but also in intact samples that had been left untreated (Figure 6, A and B) ▶ . Transmission EM images of unstripped and uncultured bronchial epithelium showed cells apparently moving between the lamina propria and the epithelium through the basement membrane pores. These pores, lined with collagen cut in a transverse section, confirmed the scanning EM images of concentric fibers lining the lumen of the pore (Figure 2 ▶ , insert). The cell in Figure 6B ▶ exhibited the hourglass morphology typical of a cell migrating through a narrow gap from a channel at the lamina reticularis/lamina propria boundary. Figure 6A ▶ shows a cell with the nucleus polarized to one end, apparently migrating in the direction of the epithelium.

Figure 6.

Transmission electron micrographs of cells traversing basement membrane through pores in a sample with an intact bronchial epithelium. Based on the positioning of their nuclei, the cells appear to be traversing into (A) and out of (B) the epithelium (E). The typical hourglass shape of one cell (B) is consistent with its migration through the limited space of the pore (arrowhead). Both pores appear to be continuous with channels (star) in the lamina propria and appear lined with collagen-like fibrils seen mostly in transverse section. LR, lamina reticularis. Scale bar, 3 μm (A and B).

Discussion

This study demonstrates the existence of pores in the basement membrane of human conducting airways. Pores were found by scanning EM in samples damaged by nonchemical means, either in vivo or during sample extraction, and also in the presence and absence of epithelium in untreated samples prepared for light and electron microscopy. Thus, the methods used to remove the epithelial cells were not responsible for the pores, nor were they artifacts of tissue processing. Although the study analyzed tissue from resection samples only, given the presence of openings in rat trachea and pores in basement membranes from a number of other human tissues, including healthy conjunctiva and inflammatory bowel disease, it seems unlikely that pores are a function only of disease. 20-22 However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the relative density of pores may reflect the severity of a disease process.

The pores were of a size, frequency, and distribution consistent with a role in normal inflammatory cell movement across the epithelial basement membrane. Their presence in basement membranes has been shown previously in colonic mucosa. 19 Using a chemical stripping method adapted from this study, we observed similar pores at a density of 863 pores/mm2. Analysis of the airway after the initial DTT incubation showed loss of ciliated and nonciliated columnar cells. To remove the basal epithelial cells required a further three incubations of EDTA with light scraping with a glass coverslip to aid detachment. The requirement for a scraping step in addition to the original method may reflect the pseudostratified structure of the bronchial epithelium or simply the greater resilience of bronchial epithelium to chemical disruption. Neither the chemical incubations nor the use of a coverslip appeared to cause any damage to the basement membrane or the underlying tissue.

The pores evident by scanning EM of stripped samples were similar in diameter to those reported previously to be present in colonic mucosa and, after analysis of nearest neighbor distances, were found to be scattered randomly across the basement membrane. 19 The nearest neighbor distance of 12.8 μm suggested that cells would not be more than 6.5 μm away from a pore and therefore, with the average diameter of an epithelial cell at approximately 5 μm, each pore may serve a total of seven epithelial cells. The relatively wide spacing of the pores, clearly distinguishable by scanning EM because of the wide field of view, probably explains why pores have not been reported previously by transmission EM studies, despite much previous literature about the ultrastructure of the respiratory tract in health and disease.

Pores may arise as a consequence of the proteolysis of basement membrane previously proposed to occur during trans-basement membrane migration. 16,17 An alternative hypothesis is that pores are an intrinsic structure of the basement membrane and are used predominantly or exclusively as migration portals into the epithelium. Consistent with this latter view, EM confirmed that pores penetrated the full depth of the basement membrane. The lamina densa layers of the basement membrane ended at the intersection with the pore; thereafter, collagen-like fibers were found, in transverse section, lining the lateral edges of the pore through the lamina reticularis. This correlated with scanning EM images showing that fibers ran in concentric circles lining the internal surface of the pore. The pore finally ended at the junction of the lamina reticularis and lamina propria, where channels could be found running parallel to the pore at the lamina reticularis/lamina propria boundary. Cells were frequently found within these channels. These observations correlate with findings in rat trachea, where the lamina reticularis was defined as a fibrous mat of predominantly collagen III with large and small openings to allow contact with fibroblasts in the lamina propria. 21

After culture for 24 hours, cells were seen in what appeared to be the early and late stages of migration through basement membrane pores. In colonic mucosa, cells were reported to pass through pores only when the epithelium had been removed and there was no report of migration into intact epithelium. 19 In the current study, transmission electron micrographs show cells appearing as if they were in the process of crossing the basement membrane into undamaged epithelium. Each cell appears within a clearly identified pore, lined with collagen-like fibrils with cellular contact established at one side of the pore only. Examples of scanning EM during the early stages of migration showed thin cell processes within identifiable pores, indicating the presence of the pore before migration. At no time were epithelial cells or epithelial cell processes observed within basement membrane pores, and the cells migrating through the basement membrane pores did not conform to the morphological characteristics of basal cells after 24 hours’ culture. Thus, basement membrane pores in respiratory epithelium appear to be selective portals for infiltrating cells in the presence or absence of damage to the epithelium.

Inflammatory cell migration into the bronchial epithelium is a characteristic feature of respiratory inflammatory diseases, especially asthma. As well as an increase in the density of eosinophils, mast cells, and T lymphocytes in the lung tissues from asthmatic patients, such cells are also found in higher numbers in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. 3 The resolution of eosinophilic inflammation in the airway is thought to involve movement of eosinophils into the lumen and their apoptosis. 23 Basement membrane pores would allow rapid inflammatory cell trans-epithelial migration into the airway lumen, without requiring enzymatic degradation of the basement membrane. The enhanced basal-to-apical movement of eosinophils during resolution suggests that basement membrane pores could provide a selective gateway for access to the airway lumen, whereas the residual eosinophils may be lost by other mechanisms such as cytolysis. 23

Movement of professional APCs into the epithelium is also important in regulating the immune response. Dendritic APCs are resident in the lung for approximately 3 days, entering the lung in an immature form to monitor the environment, capturing antigen, and thereafter migrating from the lung to the local lymph nodes, maturing as they do so. 5 Persistent pores within the basement membrane could form an integral part of a predefined network of routes between epithelial, vascular, and lymphatic systems, the channels observed at the boundary of the lamina reticularis and basement membrane being representative of this. Similar routes have been described in lymph node architecture between the vasculature and lymphatics, with a system of conduits and corridors allowing maximal contact between APCs and migrating lymphocytes. 24 Such routes in the bronchial epithelium could enhance dendritic cell/T cell and T cell/inflammatory cell interactions within the lamina propria. Cell contact would occur frequently as one cell type exits the epithelium and others enter.

The existence of such a predefined network of routes would facilitate the operation of mechanisms analogous to those seen in leukocyte trans-endothelial migration. 25 Leukocytes enter the tissue from the vascular system by attachment at sites of altered selectin and integrin expression and the presence of local chemoattractant stimuli. 25 In a similar fashion, leukocytes from the vasculature could travel by haplotaxis along routes in the lamina propria distinguished by chemokine gradients and their ability to act as substrates for cell adhesion via integrins. In response to the local mediator environment, final trans-basement membrane migration could be initiated by altered integrin expression on infiltrating cells interacting with unique combinations of matrix components on the lateral edges of the basement membrane pore.

In summary, pores are present in the basement membrane of bronchial epithelium. These pores are lined with matrix material and allow the cells from the lamina propria to cross into the epithelium without degradation of the basement membrane. Pores with some permanence within the basement membrane could allow the generation of routes within the lamina propria leading to the pore. They could act as selective conduits between epithelial and mesenchymal compartments, thus enhancing the speed and ease of cellular access to the epithelium.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Pathology Department and Biomedical Imaging Unit at Southampton General Hospital for their help and advice and Drs. A. Semper, K. Roberts, and J. Collins for critically reading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Peter M. Lackie, Division of Respiratory, Cell and Molecular Biology, MP810, Level D, Centre Block, Southampton General Hospital, SO16 6YD, United Kingdom. E-mail: p.m.lackie@soton.ac.uk.

Supported in part by Medical Research Council program grant no. G8604034 (to S. T. H.).

References

- 1.Carolan EJ, Mower DA, Casale TB: Cytokine-induced neutrophil transepithelial migration is dependent upon epithelial orientation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1997, 17:727-732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu LX, Zuurbier AEM, Mul FPJ, Verhoeven AJ, Lutter R, Knol EF, Roos D: Triple role of platelet-activating factor in eosinophil migration across monolayers of lung epithelial cells: eosinophil chemoattractant and priming agent and epithelial cell activator. J Immunol 1998, 161:3064-3070 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frew AJ, St Pierre J, Teran LM, Trefilieff A, Madden J, Peroni D, Bodey KM, Walls AF, Howarth PH, Carroll MP, Holgate ST: Cellular and mediator responses twenty-four hours after local endobronchial allergen challenge of asthmatic airways. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1996, 98:133-143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaw SK, Hermanowski-Vosatka A, Shibahara T, McCormick BA, Parkos CA, Carlson SL, Ebert EC, Brenner MB, Madara JL: Migration of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes into a polarised epithelial monolayer. Am J Physiol 1998, 38:G584-G591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holt PG, Haining S, Nelson DJ, Sedgwick JD: Origin and steady-state turnover of class II MHC-bearing dendritic cells in the epithelium of conducting airways. J Immunol 1994, 153:256-261 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erjefält JS, Sundler F, Persson CGA: Eosinophils, neutrophils, and venular gaps in the airway mucosa at epithelial removal-restitution. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996, 153:1666-1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terranova VP, Rohrbach DH, Martin GR: Role of laminin in attachment of PAM212 (epithelial) cells to basement membrane collagen. Cell 1980, 22:719-726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noguchi Y, Uchida Y, Endo T, Ninomiya H, Nomura A, Sakamoto T, Goto Y, Haraoka S, Shimokama T, Watanabe T, Hasegawa S: The induction of cell differentiation and polarity of tracheal epithelium cultured on the amniotic membrane. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1995, 210:302-309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boudreau N, Bissell MJ: Extracellular matrix signaling: integration of form and function in normal and malignant cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol 1998, 10:640-646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiser MW, Sykes DE, Killen PD: Rat intestinal basement membrane synthesis: epithelial versus non-epithelial contributions. Lab Invest 1980, 62:325-330 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laurie GW, Leblond CP: What is known of the production of basement membrane components? J Histochem Cytochem 1983, 31:159-163 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan FL, Inoue S, Leblond CP: The basement membranes of cryofixed or aldehyde-fixed, freeze-substituted tissues are composed of a lamina densa and do not contain a lamina lucida. Cell Tissue Res 1993, 273:41-52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paulsson M: Basement-membrane proteins-structure, assembly and cellular interactions. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 1992, 27:93-127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okada S, Kita H, George TJ, Gleich GJ, Leiferman KM: Migration of eosinophils through basement membrane components in vitro: role of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1997, 17:519-528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leppert D, Waubant E, Galardy R, Bunnett NW, Hauser SL: T-cell gelatinases mediate basement membrane transmigration in vitro. J Immunol 1995, 154:4379-4389 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobayashi Y, Matsumoto-Kobayashi M, Kotani M, Makino T: Possible involvement of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in Langerhans cell migration and maturation. J Immunol 1999, 163:5989-5993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heck LW, Blackburn WD, Irwin MH, Abrahamson DR: Degradation of basement membrane laminin by human neutrophil elastase and cathepsin-G. Am J Pathol 1990, 136:1267-1274 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toner PG, Carr KE, Ferguson A, Mackay C: Scanning and transmission electron microscopic studies of human intestinal mucosa. Gut 1970, 11:471-481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahida YR, Galvin AM, Gray T, Makh S, McAlindon ME, Sewell HF: Migration of human intestinal lamina propria lymphocytes, macrophages and eosinophils following the loss of surface epithelial cells. Clin Exp Immunol 1997, 109:377-386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott RAH, Lauweryns B, Snead DMJ, Haynes RJ, Mahida Y, Dua HS: E-cadherin distribution and epithelial basement membrane characteristics of the normal human conjunctiva and cornea. Eye 1997, 11:607-612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans MJ, Van Winkle LS, Fanucchi MV, Toskala E, Luck EC, Sannes PL, Plopper CG: Three-dimensional organisation of the lamina reticularis in the rat tracheal basement membrane zone. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2000, 22:393-397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McAlindon ME, Gray T, Galvin A, Sewell HF, Podolsky DK, Mahida YR: Differential lamina propria cell migration via basement membrane pores of inflammatory bowel disease mucosa. Gastroenterology 1998, 115:841-848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erjefält JS, Persson CGA: New aspects of degranulation and fates of airway mucosal eosinophils. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000, 161:2074-2085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gretz JE, Anderson AO, Shaw S: Cords, channels, corridors and conduits: critical architectural elements facilitating cell interactions in the lymph node cortex. Immunol Rev 1997, 156:11-24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Springer TA: Traffic signals for lymphocyte and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell 1994, 76:301-314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]