Abstract

Recent studies suggest that expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (Cox-2) is elevated in transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the urinary bladder and that inhibition of Cox-2 activity suppresses bladder cancer in experimental animal models. We have investigated the expression of Cox-2 protein in human TCCs (n = 85), in in situ carcinomas (Tis) of the urinary bladder (n = 17), and in nonneoplastic urinary bladder samples (n = 16) using immunohistochemistry. Cox-2 immunoreactivity was detected in 66% (67 of 102) of the carcinomas, whereas only 25% (4 of 16) of the nonneoplastic samples were positive (P < 0.005). Cox-2 immunoreactivity localized to neoplastic cells in the carcinoma samples. The rate of positivity was the same in invasive (T1–3; 70%, n = 40) and in noninvasive (Tis and Ta; 65%, n = 62) carcinomas, but noninvasive tumors had a higher frequency (32%) of homogenous pattern of staining (>90% of the tumor cells positive) than the invasive carcinomas (10%) (P < 0.05). However, several invasive TCCs exhibited the strongest intensity of Cox-2 staining in the invading cells, whereas other parts of the tumor were virtually negative. Finally, strong Cox-2 positivity was also found in nonneoplastic ulcerations (2 of 2) and in inflammatory pseudotumors (2 of 2), in which the immunoreactivity localized to the nonepithelial cells. Taken together, our data suggest that Cox-2 is highly expressed in noninvasive bladder carcinomas, whereas the highest expression of invasive tumors associated with the invading cells, and that Cox-2 may also have a pathophysiological role in nonneoplastic conditions of the urinary bladder, such as ulcerations and inflammatory pseudotumors.

Transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the urinary bladder is the third most common cancer in men and the 15th most common cancer in women accounting for 6.2 and 2.0% of the annually recorded cancer cases in Finland, respectively. 1 TCC-related deaths are mainly caused by the invasive type of the disease. However, the more frequent form of this carcinoma is either noninvasive or superficially invasive disease, which is usually curable, but demonstrates a challenge to the clinician because of its recurrent nature. Thus, more effective therapies are needed to prevent recurrence of superficial TCC and to inhibit progression of noninvasive tumors to invasive carcinomas.

Epidemiological studies suggest that the use of aspirin and other nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is associated with a reduced risk of gastrointestinal cancer. 2,3 In addition, NSAIDs can induce regression of premalignant colorectal polyps in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis, and inhibit carcinogenesis in several rodent models including those of bladder cancer. 3,4 The best known target of NSAIDs is cyclooxygenase (Cox), the rate-limiting enzyme in the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostanoids. 5,6 Two Cox genes have been cloned (Cox-1 and Cox-2) that share >60% identity at the amino acid level and have similar enzymatic activities. The most striking difference between the Cox genes is in the regulation of their expression. Although Cox-1 is constitutively expressed and the expression is not usually regulated, expression of Cox-2 is low or not detectable in most healthy tissues, but can be highly induced in response to cell activation by hormones, proinflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and tumor promoters. Thus, the pathophysiological role of Cox-2 has been connected to inflammation, reproduction, and carcinogenesis. 5-7

Recent animal studies suggest that Cox-2 expression, but not that of Cox-1, is elevated in bladder cancer. 8,9 Furthermore, NSAIDs that inhibit either preferentially or selectively Cox-2 are chemopreventive against bladder cancer in the rat. 10,11 Elevated Cox-2 expression has been described in several human malignancies. 5,7,12 However, in the case of bladder cancer, the data are inconsistent in respect of the presence of Cox-2 expression in in situ carcinomas (Tis), and whether Cox-2 is expressed in low-grade and in noninvasive TCCs. 13-15 The purpose of this study was to investigate the expression of Cox-2 in both noninvasive and invasive TCC and in nonneoplastic lesions of the bladder using immunohistochemistry and a Cox-2-specific monoclonal antibody combined with the use of appropriate control experiments.

Materials and Methods

Patient Samples

Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded urinary-bladder tissue specimens from patients with invasive TCC (T1, T2, and T3; n = 40), noninvasive carcinomas (Tis or Ta; n = 62), and 16 nonneoplastic conditions (eight cystitis, two ulcerations, two inflammatory pseudotumors, and four samples with normal histology) were obtained from the files of the Department of Pathology, Helsinki University Central Hospital (Table 1) ▶ . The age of the carcinoma patients was 71 ± 13 years (mean ± SD; range, 42 to 95 years) and that of patients with nonneoplastic lesions 67 ± 18 years (range, 25 to 94 years). Of the TCC patients 25 were women and 77 men, and in the nonneoplastic group there was three women and 13 men. Twenty of the specimens were taken at radical cystectomy and the rest were transurethral biopsies. Grade (G1–3) of the tumor was determined according to the World Health Organization classification, 16 and by the more recent (low and high grade) World Health Organization/International Society of Urologic Pathologists consensus classification for the urothelial neoplasms. 17 All samples were reassessed by a pathologist (SN).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Urinary Bladder Carcinomas and Results of Cox-2 Immunohistochemistry

| Type | No. of patients | Cox-2 positivity (No.) | Positive for Cox-2 | Area of Cox-2 positivity >90% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Weak positive | Strong positive | ||||

| Stage | ||||||

| Tis | 17 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 71% | 53% |

| Ta | 45 | 18 | 22 | 5 | 60% | 24% |

| T1 | 21 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 62% | 14% |

| T2 | 12 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 75% | 0% |

| T3 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 86% | 14% |

| Grade (WHO) | ||||||

| G1 | 22 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 59% | 32% |

| G2 | 48 | 17 | 23 | 8 | 65% | 23% |

| G3 | 32 | 9 | 16 | 7 | 72% | 19% |

| All carcinoma cases | 102 | 35 | 48 | 19 | 66% | 24% |

Immunohistochemistry

The specimens were sectioned (4 μm), deparaffinized, and microwaved for 4 × 5 minutes at 700 W in 0.01 mol/L Na-citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for antigen retrieval. The slides were then immersed in 0.6% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 30 minutes to block endogenous peroxidase activity and in blocking solution [1.5:100 normal horse serum in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] for 15 minutes to block unspecific binding sites. Immunostaining was performed with Cox-2-specific anti-human monoclonal antibody (160112; Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI) in a dilution of 1:200 (2.5 μg/ml) in PBS containing 0.1% sodium azide and 0.5% bovine serum albumin at room temperature overnight. Then the sections were treated with biotinylated horse anti-mouse immunoglobulin (1:200; Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA) and avidin-biotin peroxidase complex (Vectastain ABComplex, Vector Laboratories). The peroxidase staining was visualized with 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), and the sections were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin. The specificity of the antibody was determined by pre-adsorption of the primary antibody with human Cox-2 control peptide (1 to 10 μg/ml, Cayman Chemical) for 1 hour at room temperature before the staining procedure. An α-smooth muscle cell actin peptide (50 μg/ml; DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) was used as a non-Cox-2 peptide.

The intensity of the Cox-2 immunoreactivity was graded negative, weakly positive, or strongly positive, reflecting both the intensity of staining as well as the amount of positive cells in consensus of two investigators (SN and AR). In addition, the proportion of Cox-2-positive tumor cells was estimated (<10%, 10 to 90%, >90%).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was calculated using the Fisher’s exact test, and P < 0.05 was selected as the statistically significant value.

Results

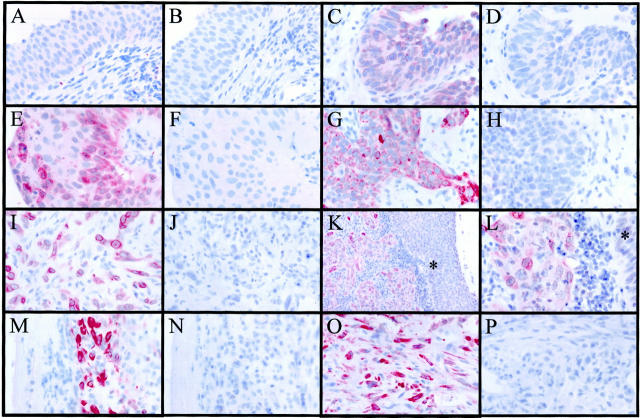

Expression of Cox-2 protein was investigated in 102 carcinoma specimens and in 16 nonneoplastic samples of the human urinary bladder using immunohistochemistry (Figure 1) ▶ . Cox-2 immunoreactivity was detected in 66% (67 of 102) of the carcinomas (Table 1) ▶ , whereas only 25% (4 of 16) of the nonneoplastic samples were positive (P < 0.005). Cox-2 immunoreactivity localized almost exclusively to the neoplastic cells in the TCCs, whereas the stroma of the tumors was negative (Figure 1, G to L) ▶ . Although 19% of the TCC specimens stained with high intensity, none of the nonneoplastic specimens showed strong staining in the epithelial cell compartment. The rate of positivity was the same in invasive (T1–3; 70%, n = 40) and in noninvasive (Tis or Ta; 65%, n = 62) TCCs. However, only 24% (24 of 102) of the TCCs exhibited homogenous staining (>90% of the tumor cells positive), suggesting that the staining pattern of Cox-2 is relatively heterogeneous. Interestingly, noninvasive specimens exhibited a higher frequency (32%, 20 of 62) of homogenous staining than the invasive TCCs (10%, 4 of 40) (P < 0.05). Furthermore, several invasive TCCs exhibited the strongest intensity of Cox-2 staining in the invading cells (1 of 45 of T1, 2 of 12 of T2, and 4 of 7 of T3), whereas other parts of the tumor expressed low or undetectable levels of the protein. No statistically significant difference in the Cox-2 positivity was found between different grades of the TCCs when either World Health Organization classification (Table 1) ▶ or World Health Organization/ISUP consensus classification were used (low-grade tumors were 61% and high-grade neoplasms 69% positive for Cox-2). In addition to the neoplastic epithelial cells of the TCCs, strong Cox-2 positivity was present at sites of nonneoplastic ulcerations (2 of 2) and in inflammatory pseudotumors (2 of 2), in which the immunoreactivity localized to the nonepithelial cells (Figure 1, M to P) ▶ . The pattern of the Cox-2 immunoreactivity in both neoplastic and nonneoplastic cells was of diffuse cytoplasmic type with occasional perinuclear staining (Figure 1; G, I, and L ▶ ). The specificity of the monoclonal antibody was confirmed by staining the specimens with and without pre-adsorption with the antigenic peptide, which blocked virtually all immunoreactivity obtained by the antibody (Figure 1 ▶ and data not shown). A peptide unrelated to Cox-2 did not reduce the immunoreactivity obtained by the monoclonal antibody.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical detection of Cox-2 protein in the human urinary bladder specimens using a Cox-2-specific monoclonal antibody. A: Normal transitional cell epithelium was negative or stained with weak intensity (B, pre-adsorption control using an antigenic peptide). C to L: Cox-2 immunoreactivity localized to the neoplastic cells in the TCC specimens, but tumor stroma remained negative. C: In situ carcinoma (D, the pre-adsorption control). E: Noninvasive (Ta) carcinoma (F, the pre-adsorption control). G: Invasive (T1) carcinoma (H, the pre-adsorption control). I: Invading cells of a T3 carcinoma (J, the pre-adsorption control). K and L: Cox-2 positivity in an invasive (T3) carcinoma, whereas normal transitional cell epithelial cells (asterisks) remained essentially negative. M to P: Strong Cox-2 positivity at sites of nonneoplastic ulcerations and in inflammatory pseudotumors, in which the immunoreactivity localized to the nonepithelial cells. M: Ulceration (N, the pre-adsorption control). O: Inflammatory pseudotumor (P, the pre-adsorption control). Original magnifications: ×600 (A–J and L–P ) and ×200 (K).

Discussion

Our data indicate that Cox-2 is expressed in 65% of human TCCs (Ta and T1–4) as detected by immunohistochemistry. The Cox-2 immunoreactivity localized to the neoplastic cells, whereas the tumor stroma was negative. Importantly, all immunoreactive signal obtained by the Cox-2-specific monoclonal antibody was blocked by the antigenic Cox-2 peptide, but not by an unrelated peptide. Our data are consistent with previously published reports that indicate that 34 to 84% of TCCs are positive for Cox-2 as detected by immunohistochemistry or immunoblotting. 13-15 Furthermore, it has been reported that no Cox-2 expression is evident in nonneoplastic epithelium of the human, rodent, or canine urine bladder, 8,9,13,15 although one report indicated a relatively high frequency (53%) of Cox-2 expression in nonneoplastic epithelium adjacent to the tumor. 13 We found that the normal transitional cell epithelium was virtually negative for Cox-2 in both nonneoplastic and neoplastic specimens. However, we did find strong expression of Cox-2 at sites of nonneoplastic ulcerations and in inflammatory pseudotumors, but in contrast to the carcinomas, this injury- and inflammation-associated Cox-2 expression localized to the nonepithelial (inflammatory and connective tissue) cells. Thus, although the stroma of the bladder carcinomas was negative for Cox-2, we were able to detect Cox-2 expression in the stromal cells when they were appropriately activated. Because expression of Cox-2 has been associated with ulcer healing in the gastrointestinal tract and its expression is enhanced by various proinflammatory agents, 5 expression of Cox-2 in nonneoplastic bladder lesions may be related to healing process present at the site of ulceration and because of inflammatory activity in pseudotumors.

The chemopreventive effect of NSAIDs may be targeted to early lesions, because they induce regression of premalignant colorectal polyps in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis and in experimental animal models of this disease. 3,7,18 Cox-2 is also expressed in epithelial cells of preneoplastic dysplasias and in situ carcinomas of the stomach (unpublished results), 19, 20 esophagus, 21-23 and lung. 24,25 Furthermore, it is expressed in chemically induced preneoplastic lesions of the lung and in the urinary bladder of the rat. 8,26 However, although it is the carcinoma cells that express the highest level of Cox-2 in colorectal cancer, Cox-2 seems to localize to the stromal and to a lesser extent to the epithelial cells in colonic adenomas. 27-29 We found that Cox-2 is expressed in 71% of the Tis and in 60% of the Ta carcinomas. This is consistent with data published by Mohammed and colleagues 13 and by Shirahama, 15 who found 75 and 93% of Tis carcinomas to be positive for Cox-2 as detected by immunohistochemistry and by immunoblotting, respectively. However, our data differ from those published by Kömhoff and colleagues, 14 who did not detect any Cox-2 expression in noninvasive (Ta) or low-grade TCCs. In fact, we found a higher frequency of homogenous Cox-2 staining in the Tis and Ta tumors when compared to the invasive carcinomas. Discrepancies of the immunohistochemistry data may depend on the use of different antibodies and/or staining methods that affect both sensitivity and specificity. A more detailed description about the performance of different Cox-2 antibodies is beyond the scope of this paper. However, in respect of invasive carcinomas, we did find expression of Cox-2 to be high in invading cells of the invasive tumors, even when the rest of the tumor is negative for Cox-2. Interestingly, expression of Cox-2 may be related to invasion and metastasis of carcinomas, 30-33 which could potentially be connected to increased production and activation of matrix metalloproteinases as shown by overexpression of Cox-2 in cancer cell lines. 34,35

All this indicates that Cox-2 is highly expressed in noninvasive TCCs, and that it may contribute to the invasive potential of more advanced carcinomas. Because inhibition of Cox-2 is chemopreventive in animal models of urinary bladder cancer, 11 further studies are required to evaluate whether Cox-2-targeted therapy might prove to be effective against human TCC.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kaija Antila, Tuija Hallikainen, Elina Laitinen, and Sari Nieminen for excellent technical assistance; and Bastiaan van Rees for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Ari Ristimäki, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Helsinki University Central Hospital, P.O. Box 140, FIN-00029 Helsinki, Finland. E-mail: ari.ristimaki@hus.fi.

Supported by the Helsinki University Central Hospital Research Funds, the Finnish Cancer Foundation, and Finska Läkaresällskapet. K. S. received support from the Helsinki University Biomedical Graduate School.

O. N. and K. S. contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Finnish Cancer Registry—The Institute for Statistical and Epidemiological Cancer Res: Cancer incidence in Finland 1995. Cancer Statistics of the National Research and Development Center for Welfare and Health. Helsinki, Cancer Society of Finland publication No. 58, 1997

- 2.Thun MJ: Aspirin, NSAIDs, and digestive tract cancers. Cancer Metastasis Rev 1994, 13:269-277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giardiello FM, Offerhaus GJA, DuBois RN: The role of nonsteroidal anti inflammatory drugs in colorectal cancer prevention. Eur J Cancer 1995, 31:1071-1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.IARC Handbooks on Cancer Prevention, vol 1: Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Lyon, International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1997

- 5.Dubois RN, Abramson SB, Crofford L, Gupta RA, Simon LS, Van De Putte LB, Lipsky PE: Cyclooxygenase in biology and disease. FASEB J 1998, 12:1063-1073 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taketo MM: Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in tumorigenesis (part I). J Natl Cancer Inst 1998, 90:1529-1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taketo MM: Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in tumorigenesis (part II). J Natl Cancer Inst 1998, 90:1609-1620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitayama W, Denda A, Okajima E, Tsujiuchi T, Konishi Y: Increased expression of cyclooxygenase-2 protein in rat urinary bladder tumors induced by N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl) nitrosamine. Carcinogenesis 1999, 20:2305-2310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan KN, Knapp DW, Denicola DB, Harris RK: Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder in dogs. Am J Vet Res 2000, 61:478-481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okajima E, Denda A, Ozono S, Takahama M, Akai H, Sasaki Y, Kitayama W, Wakabayashi K, Konishi Y: Chemopreventive effects of nimesulide, a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, on the development of rat urinary bladder carcinomas initiated by N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl)nitrosamine. Cancer Res 1998, 58:3028-3031 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grubbs CJ, Lubet RA, Koki AT, Leahy KM, Masferrer JL, Steele VE, Kelloff GJ, Hill DL, Seibert K: Celecoxib inhibits N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl)-nitrosamine-induced urinary bladder cancers in male B6D2F1 mice and female Fischer-344 rats. Cancer Res 2000, 60:5599-5602 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koki AT, Leahy KM, Masferrer JL: Potential utility of Cox-2 inhibitors in chemoprevention and chemotherapy. Exp Opin Invest Drugs 1999, 8:1623-1638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohammed SI, Knapp DW, Bostwick DG, Foster RS, Khan KNM, Masferrer JL, Woerner BM, Snyder PW, Koki AT: Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in human invasive transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the urinary bladder. Cancer Res 1999, 59:5647-5650 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kömhoff M, Guan Y, Shappell HW, Davis L, Jack G, Shyr Y, Koch MO, Shappell SB, Breyer MD: Enhanced expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in high grade human transitional cell bladder carcinomas. Am J Pathol 2000, 157:29-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shirahama T: Cyclooxygenase-2 expression is up-regulated in transitional cell carcinoma and its preneoplastic lesions in the human urinary bladder. Clin Cancer Res 2000, 6:2424-2430 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mostofi FK, Sobin LH, Torloni H: Histological typing of urinary bladder tumours. International Classification of Tumors, 1973, vol 19. World Health Organization, Geneva

- 17.Epstein JI, Amin MB, Reuter VR, Mostofi FK: The World Health Organization/International Society of Urological Pathology consensus classification of urothelial (transitional cell) neoplasms of the urinary bladder. Bladder Consensus Conference Committee. Am J Surg Pathol 1998, 22:1435-1448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinbach G, Lynch PM, Phillips RK, Wallace MH, Hawk E, Gordon GB, Wakabayashi N, Saunders B, Shen Y, Fujimura T, Su LK, Levin B: The effect of celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, in familial adenomatous polyposis. N Engl J Med 2000, 342:1946-1952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ristimäki A, Honkanen N, Jänkälä H, Sipponen P, Härkönen M: Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in human gastric carcinoma. Cancer Res 1997, 57:1276-1280 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim HY, Joo HJ, Choi JH, Yi JW, Yang MS, Cho DY, Kim HS, Nam DK, Lee KB, Kim HC: Increased expression of cyclooxygenase-2 protein in human gastric carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2000, 6:519-525 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson KT, Fu S, Ramanujam KS, Meltzer SJ: Increased expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 in Barrett’s esophagus and associated adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res 1998, 58:2929-2934 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shirvani VN, Ouatu-Lascar R, Kaur BS, Omary MB, Triadafilopoulos G: Cyclooxygenase 2 expression in Barrett’s esophagus and adenocarcinoma: ex vivo induction by bile salts and acid exposure. Gastroenterology 2000, 118:487-496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shamma A, Yamamoto H, Doki Y, Okami J, Kondo M, Fujiwara Y, Yano M, Inoue M, Matsuura N, Shiozaki H, Monden M: Up-regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 in squamous carcinogenesis of the esophagus. Clin Cancer Res 2000, 6:1229-1238 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hida T, Yatabe Y, Achiwa H, Muramatsu H, Kozaki K, Nakamura S, Ogawa M, Mitsudomi T, Sugiura T, Takahashi T: Increased expression of cyclooxygenase 2 occurs frequently in human lung cancers, specifically in adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res 1998, 58:3761-3764 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolff H, Saukkonen K, Anttila S, Karjalainen A, Vainio H, Ristimäki A: Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in human lung carcinoma. Cancer Res 1998, 58:4997-5001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitayama W, Denda A, Yoshida J, Sasaki Y, Takahama M, Murakawa K, Tsujiuchi T, Tsutsumi M, Konishi Y: Increased expression of cyclooxygenase-2 protein in rat lung tumors induced by N-nitrosobis(2-hydroxypropyl)amine. Cancer Lett 2000, 148:145-152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sano H, Kawahito Y, Wilder RL, Hashiramoto A, Mukai S, Asai K, Kimura S, Kato H, Kondo M, Hla T: Expression of cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 1995, 55:3785-3789 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shattuck-Brandt RL, Lamps LW, Heppner Goss KJ, DuBois RN, Matrisian LM: Differential expression of matrilysin and cyclooxygenase-2 in intestinal and colorectal neoplasms. Mol Carcinog 1999, 24:177-187 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chapple KS, Cartwright EJ, Hawcroft G, Tisbury A, Bonifer C, Scott N, Windsor AC, Guillou PJ, Markham AF, Coletta PL, Hull MA: Localization of cyclooxygenase-2 in human sporadic colorectal adenomas. Am J Pathol 2000, 156:545-553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujita T, Matsui M, Takaku K, Uetake H, Ichikawa W, Taketo MM, Sugihara K: Size- and invasion-dependent increase in cyclooxygenase 2 levels in human colorectal carcinomas. Cancer Res 1998, 58:4823-4826 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hida T, Yatabe Y, Achiwa H, Muramatsu H, Kozaki K, Nakamura S, Ogawa M, Mitsudomi T, Sugiura T, Takahashi T: Increased expression of cyclooxygenase 2 occurs frequently in human lung cancers, specifically in adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res 1998, 58:3761-3764 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murata H, Kawano S, Tsuji S, Tsuji M, Sawaoka H, Kimura Y, Shiozaki H, Hori M: Cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression enhances lymphatic invasion and metastasis in human gastric carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 1999, 94:451-455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryu HS, Chang KH, Yang HW, Kim MS, Kwon HC, Oh KS: High cyclooxygenase-2 expression in stage IB cervical cancer with lymph node metastasis or parametrial invasion. Gynecol Oncol 2000, 76:320-325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsujii M, Kawano S, DuBois RN: Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human colon cancer cells increases metastatic potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997, 94:3336-3340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takahashi Y, Kawahara F, Noguch M, Miwa K, Sato H, Seiki M, Inoue H, Tanabe T, Yoshimoto T: Activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in human breast cancer cells overexpressing cyclooxygenase-1 or -2. FEBS Lett 1999, 460:145-148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]