Abstract

Laminin 5 is a pivotal hemidesmosomal protein involved in cell stability, migration, and anchoring filament formation. Protein and gene expression of the α3, β3, and γ2 chains of laminin 5 were investigated in normal and invasive prostate carcinoma using immunohistochemistry, Northern analysis, and in situ hybridization. Laser capture microdissection of normal and carcinomatous glands, in conjunction with RNA amplification and reverse Northern analysis, were used to confirm the gene expression data. Protein and mRNA expression of all three laminin 5 chains were detected in the basal cells of normal glands. In contrast, invasive prostate carcinoma showed a loss of β3 and γ2 protein expression with variable expression of α3 chains. Despite the loss of protein expression, there was retention of β3 and γ2 mRNA expression as detected by in situ hybridization, Northern and reverse Northern analysis. Our findings imply that an altered mechanism of translation of β3 or γ2 mRNAs into functional proteins contributes to failure of anchoring filaments and hemidesmosomal formation. The resultant hemidesmosome instability or loss would suggest a less stable epithelial-stromal junction, increased invasion and migration of malignant cells, and disruption of normal integrin signaling pathways.

Laminins are components of the extracellular matrix that contribute to the architecture of the basal lamina (BL), and mediate cell adhesion, growth, migration, proliferation, and differentiation. 1 These molecules are heterotrimers consisting of α, β, and γ chains. Given the existence of 11 genetically distinct chain forms (α1 to α5, β1 to β3, and γ1 to γ3), 2-4 different combinations of chains could result in up to 45 different heterotrimeric isoforms. Only 13 laminin isoforms (laminins 1, 2, 4 to 12, 14, 15), however, have thus far been convincingly demonstrated. 3-6 Some laminins, such as laminin 10 (α5β1γ1), are ubiquitously present in BL, whereas other laminins demonstrate considerable tissue specificity. Laminin 5 (α3β3γ2), for example, is restricted to the BL of stratified and certain other epithelia, and is one of the primary hemidesmosomal proteins. 2 The N-terminus of the α3 chain serves as the collagen VII attachment site for anchoring fibril formation. 7 The globular domain of the laminin 5 α3 chain is the putative binding site for the α6β4 and α3β1 integrin receptors. The α6β4 integrin/laminin 5 complex is essential for signal transduction. 8-11 In addition to monomeric molecules, laminin 5 is frequently found covalently associated with laminin 6 (α3β1γ1) and laminin 7 (α3β2γ1). 12

Direct evidence for the crucial role of laminin 5 in maintaining the integrity of the BL has come from the identification of mutations in the laminin 5 genes observed in the Herlitz’s variant of junctional epidermolysis bullosa, a blistering and usually lethal skin disease caused by disruption of the epidermal-dermal junction. In Herlitz’s variant of junctional epidermolysis bullosa, genetic disruptions associated with the observed pathology have been associated with the presence of premature stop codons, or frameshift mutations on both alleles of any of the three genes encoding the chains of laminin 5. 13,14 Mutations resulting in the failure of expression of any of these three chains results in a complete absence of laminin 5 immunoreactivity and to ultrastructural changes in hemidesmosomes. 15

Laminin 5 has revealed variable patterns of expression in tumors derived from different tissues. In gliomas and carcinomas of the colon, stomach, and squamous epithelium, laminin 5 has been observed to be highly expressed and located at the invasive edge of the tumor. 16-19 In sharp contrast, laminin 5 expression is down-regulated in basal cell and squamous carcinomas, as well as in carcinomas of breast and prostate. 20-25

We have shown that the BL circumscribing normal prostate glands differs from the BL surrounding prostate carcinoma in that several extracellular matrix proteins are not detected in carcinoma. 26,27 Prostate tumor progression probably involves changes that occur within the de novo synthesized extracellular matrix of the BL of prostate carcinoma. These changes include the loss of laminin 5 expression, 23,26 which leads to cytoplasmic membrane instability of its integrin receptor α6β4, 28 and to alterations in cell signaling. We have shown a simultaneous loss of laminin 5, collagen VII, and β4-integrin protein expression in prostate carcinoma. 28 We conducted this study to clarify the mechanism explaining the loss of laminin 5 protein expression in prostate carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry, Northern analysis, and in situ hybridization were used to investigate gene expression. Moreover, individual selected normal and carcinoma glands underwent LCM. RNA isolated from these glands was amplified and examined by reverse Northern analysis.

Materials and Methods

Immunohistochemistry

Freshly obtained surgical samples of normal and malignant human prostate tissue were snap-frozen in an isopentane bath cooled by Freon, sectioned, and examined using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining to select normal areas and invasive carcinoma. Frozen 5-μm sections of human prostate samples containing both normal tissue and carcinomas were reacted with primary antibodies followed by binding with secondary antibodies conjugated to biotin. Streptavidin-diaminobenzidine was subsequently used to detect the antibody complex. Sources and dilutions of antibodies against the α3, β3, and γ2 chains of laminin 5 are listed in Table 1 ▶ .

Table 1.

Antibodies Used in this Study

| Specificity | Clone | Type | Dilution | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α3 of L5 | BM2(BM165) | mAb | 1:100 | Dr. R.E. Burgeson, Harvard Medical School |

| β3 of L5 | 6F12(BM140) | mAb | 1:100 | Dr. R.E. Burgeson, Harvard Medical School |

| γ2 of L5 | GB3 | mAb | 1:15 | Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corp |

| γ2 of L5 | J20 | Polyclonal | 1:100 | Dr. Jonathan Jones, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL |

| γ2 of L5 | D4B5 | mAb | 1:100 | Chemicon International, Inc. |

Cell Culture

Normal human prostate epithelial cells (PrE4428) were obtained from Clonetics Corp. (San Diego, CA). The cultured cells were maintained in PrEGM medium from Clonetics Corp. at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air, 5% CO2.

Preparation of Riboprobes

To construct sense and antisense probes for the α3, β3, and γ2 chains of laminin 5, chain-specific cDNA clones (Table 2) ▶ were subcloned into the pBluescript SKII transcription vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The sequences of the subclones were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The plasmids were then linearized and sense and antisense probes were synthesized using either T3 or T7 RNA polymerase, respectively. For in situ hybridization, the antisense and sense probes were labeled with digoxigenin-UTP (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) as previously described. 23

Table 2.

Probes Used in this Study

| cDNA clones | Specificity | Regions as probes | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| EP-1 | α3 of Lm-5 | 1183–1701 bp | Dr. M.C. Ryan, Seattle, WA |

| 5-5 | β3 of Lm-5 | −171–2202 bp | Dr. D. Gerecke, Charlestown, MA |

| 92-1 | β3 of Lm-5 | 2005–3751 bp | Dr. D. Gerecke, Charlestown, MA |

| pL4 | γ2 of Lm-5 | 583–2527 bp | Dr. K. Tryggvason, Oulu, Finland |

In Situ Hybridization

In situ hybridization with digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes was performed as previously described. 23

Northern Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from PrEC4428 cells as well as from microdissected areas of primary prostate carcinoma and adjacent normal prostate from three different patients. RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Inc, Gaithersburg, MD). Approximately 20 μg of total RNA was loaded in each lane, separated on a 1.2% agarose/formaldehyde gel, and transferred to nylon membrane (Life Technologies, Inc.). The blots were probed with α32P-dCTP-labeled cDNA probes specific for the β3 and γ2 chains of laminin 5, and GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase). Total RNA from PrEC4428 was used as a positive control for probe specificity, and GAPDH hybridization was used as a loading control. Hybridization was performed at 42°C in 50% formamide, 2× standard saline citrate (SSC), 5× Denhardt’s, and 20 μg/ml of salmon sperm DNA. Posthybridization washes were performed in 2× SSC/0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at 50°C for 30 minutes, followed by 0.1× SSC/0.1% SDS at 55°C for 30 minutes.

Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM) and Reverse Northern Analysis LCM and RNA Isolation

Five-micron cryostat sections of snap-frozen prostate tissue samples were applied to positively charged glass slides. Sections were stained by H&E according to slightly modified National Institutes of Health protocols (http://www.arctur.com for hematoxylin and eosin staining protocols; http://dir.nichd.nih.gov/lcm/LCMTAP.htm for LCM preparation and analysis). Laser capture of target cells was performed using the PixCell II image archiving system (Arcturus Engineering, Mountain View, CA) as previously described. 29 Total RNA was extracted from laser-captured cells using the Micro RNA isolation kit (Stratagene, San Diego, CA). 30 Image archiving and LCM recovery of ∼1500 cells per sample from prostatic carcinoma and adjacent normal glandular epithelium was found to provide sufficient mRNA to detect, using two rounds of amplification.

RNA Amplification and Reverse Northern Blot Analysis

The purified RNA sample underwent amplification using 0.5 μg/μl of T7-oligo dT primer, Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Inc.), and Ampliscribe T7 transcription kit (Epicentre Technologies, Madison, WI) as previously described. 30 Ten μl of purified, resultant amplified RNA (aRNA) underwent second-round amplification using pdN6 random hexamers (1 μg/μl; Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) during first-strand synthesis, and T7-oligo dT primer for the second-strand reaction, as previously described. 30

Second-round aRNA specimens were synthesized into randomly labeled α32P-dCTP probes using pdN6 random hexamers (1 μg/μl; Pharmacia) and the Superscript preamplification system reagents (Life Technologies, Inc.) as previously described. 31 Target cDNA (0.5 μg) was cross-linked to the blot membrane with a UV Stratalinker 2400 (Stratagene). The positive control for each blot consisted of 0.5 μg of GAPDH. The negative control was single-strand antisense laminin 5 β3 cDNA.

Reverse Northern blots were performed as previously described. 31 In brief, 500 ng of target cDNAs including controls were denatured, combined with 111 μl of sterile water, 80 μl of 1 mol/L NaOH, and 4 μl of 0.5 mol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and cross-linked to an Ambion Bright Star Plus positively charged nylon membrane (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX) using a Minifold II slot-blot apparatus (Schleicher and Schuell, Keene, NH). The membranes were prehybridized at 68°C for 45 minutes in Perfect Hyb Plus solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Radiolabeled cDNA probe was denatured at 100°C for 10 minutes, added to the prehybridization mixture, and hybridized overnight at 68°C in Perfect Hyb Plus solution. The membrane was washed twice for 20 minutes each in 2× SSC/0.1% SDS at 68°C for 15 minutes. Higher stringency washes were performed in sequence as necessary to remove background signals from the membrane, including two 0.2× SSC/0.1% SDS washes at 68°C for 15 minutes, and two 0.1× SSC/0.1% SDS washes at 68°C for 15 minutes. The blots were then exposed on phosphorimaging screens (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). Each blot was measured and plotted with a Phosphorimage 445SI scanner (Molecular Dynamics). Blots were stripped and reprobed up to four times.

Results

Laminin 5 Protein Expression

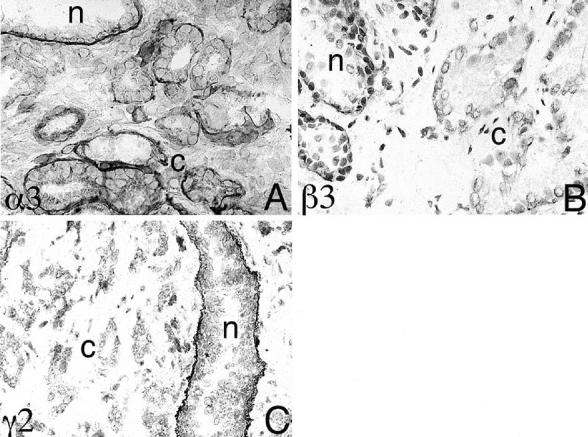

Twenty-five surgical specimens containing invasive carcinomas and adjacent nonmalignant glands were examined by immunohistochemistry. Monoclonal antibodies BM165 and 6F12, and polyclonal antibody J20 enabled the detection of α3, β3, and γ2 chains of laminin 5, respectively. An additional five cases were stained with the g2 chain-specific antibody (Chemicon, Temecula, CA). The results showed variable protein expression of the α3 chain in both normal and neoplastic prostate epithelium, but the β3 and γ2 chains were not detected in invasive carcinoma (Figure 1) ▶ .

Figure 1.

Differential expression of laminin 5 chains by human prostate. A–C: Immunohistochemical staining using mAb BM165 (α3), BM140 (β3), and polyclonal antibody J20 (γ2). Note in A the protein for the α3 chain of laminin 5 is retained by both normal prostate epithelium (n) and variably by prostate carcinoma (c), but the β3 and the γ2 chains were not detected in invasive carcinoma (B and C). Original magnification, ×100.

Laminin 5 mRNA Expression

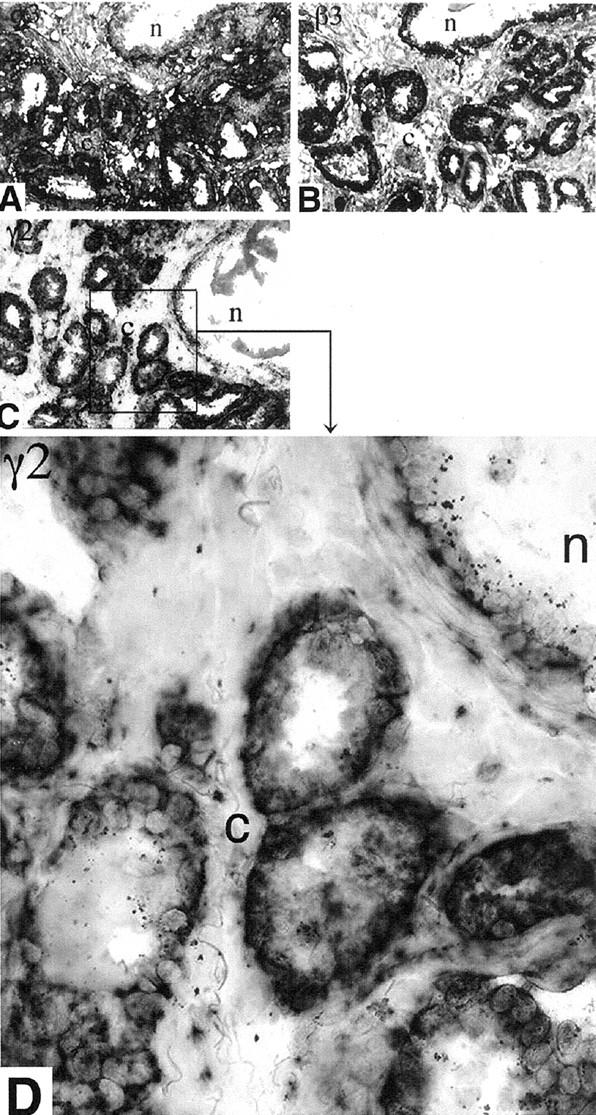

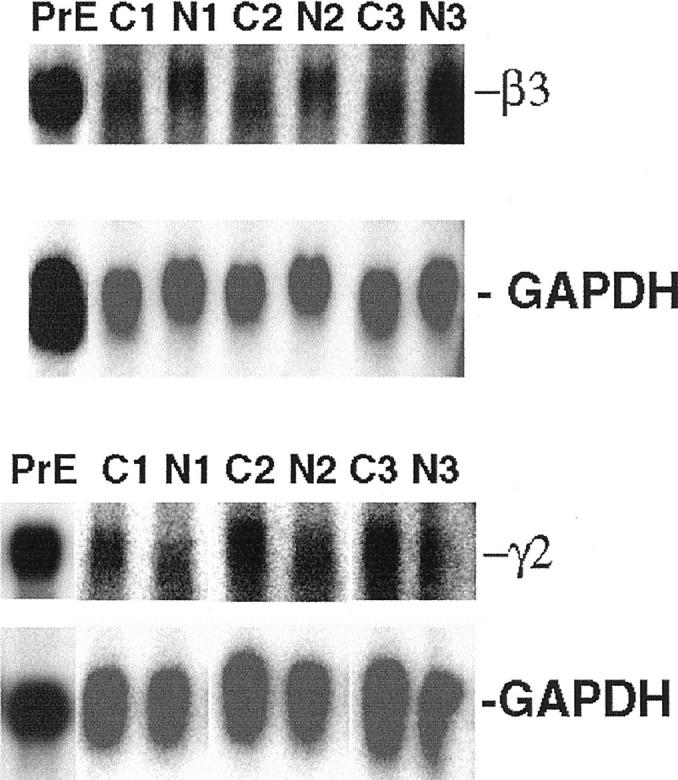

In situ hybridization experiments performed on six cases of prostate carcinoma showed the presence of mRNAs for the α3, β3, and γ2 chains of laminin 5. The mRNAs were present in all of the carcinomas studied, as well as in the basal cells of normal glands (Figure 2 ▶ ; A–C). The level of expression of the γ2 message seemed to be higher in the carcinoma cells than in normal glandular epithelium (Figure 2, C and D) ▶ . Adjacent serial sections reacted with control sense probes were consistently negative. Northern analysis confirmed the presence of the β3 and γ2 mRNAs of laminin 5 in both normal prostate and prostate carcinomas (Figure 3) ▶ .

Figure 2.

In situ hybridization using chain-specific laminin 5 probes. In situ hybridization was performed using digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA probes of the laminin 5. A: α3. B: β3. C: γ2. The mRNAs of the three chains are present in normal glands (n) as well as in the invasive carcinoma (c). D: Higher magnification of the area of C designated by the black box showing that the level of expression of the γ2 message appears to be higher in the carcinoma cells than in normal glandular epithelium. Original magnifications, ×100 (A–C) and ×400 (D).

Figure 3.

Northern analysis of laminin 5 β3 and γ2 chain expression in human prostate. Total RNA was isolated from the normal prostate epithelial cell line, PrEC 4428, and from three cases of prostate carcinoma and adjacent normal tissue. The Northern blot was probed with 32P-dCTP-labeled cDNA probes specific for the β3 and γ2 chains of laminin 5, and GADPH. Total RNA from normal prostate epithelial cell line, PrEC 4428, was used as positive control, and GAPDH hybridization was used as a loading control. Northern analysis confirmed the presence of the β3 and γ2 mRNAs of laminin 5 in both normal prostate and prostate carcinomas.

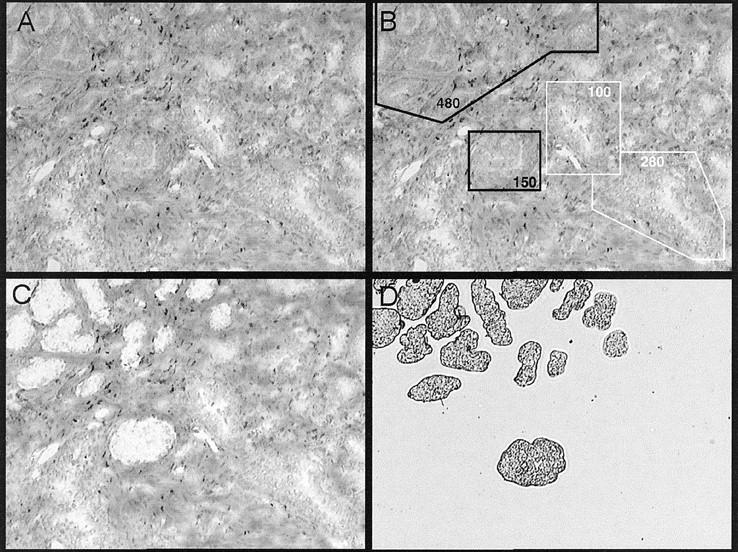

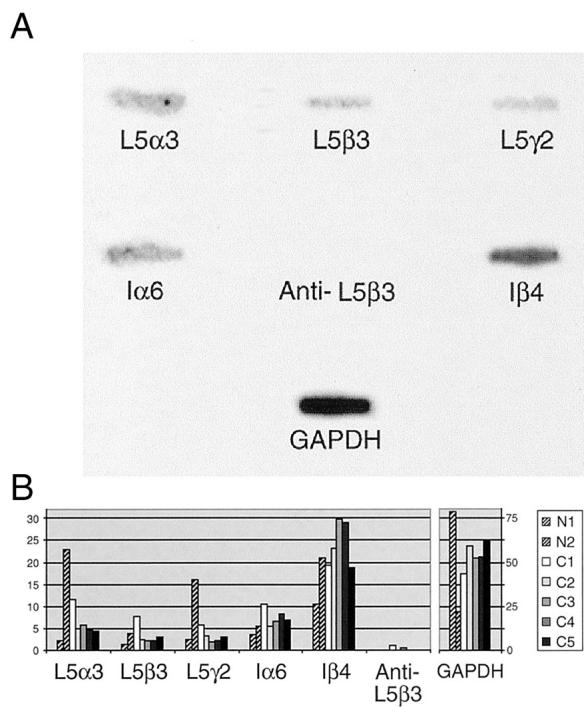

Samples of normal glands from two patients and malignant glands from five patients with adenocarcinoma of the prostate were isolated by LCM (Figure 4) ▶ . Figure 5A ▶ presents a representative reverse Northern blot of one case of malignant tissue. Figure 5B ▶ summarizes the quantitation of cDNA band phosphor intensities from the two normal samples (N1 and N2) and five malignant samples (C1 to C5). Individual band intensities were expressed as a percentage of the total intensity of all seven possible bands on a single blot. Standardized amounts of target cDNA and identical conditions for probe and target cDNA production enabled band intensity data to be used as relative indicators of the amount of mRNA present in the laser-captured samples before amplification.

Figure 4.

LCM of prostate carcinoma. Laser capture of target cells was performed using the PixCell II image archiving system on 5-μm cryostat sections of snap-frozen prostate tissue stained by H&E. A: H&E-stained section before LCM. B: Target areas identified as carcinoma by H&E staining are designated by black boxes. Normal glands targeted for capture are surrounded by white boxes. C: White areas of H&E section are the holes left after carcinoma glands have been laser-captured and then transferred to cap surface (D). Original magnification, ×100.

Figure 5.

Reverse Northern blot of laser-captured prostate glands. A: Reverse Northern slot blot of one representative case of malignant prostate tissue. Probe samples were obtained by laser-captured microdissection of ∼1500 cells from sections of snap-frozen prostate tissue. GAPDH and antisense laminin 5 β3 sequences served as positive and negative controls, respectively. Band intensity serves as a relative indicator of the amount of message RNA present in the laser-captured sample before amplification. B: Summary of reverse Northern blot data showing comparative quantitation of cDNA probe phosphor intensities of normal (NL) and carcinoma (Ca). Two representative normal samples (N1 and N2) and five malignant samples (C1 to C5) are arranged by individual (rows) and type of target cDNA (columns). Individual band intensities are expressed as a percentage of the intensity of all seven possible bands on the blot from which it came.

Inspection of this data revealed that mRNAs for the laminin 5 α3, β3, and γ2 chains, α6 and β4 integrins, and GAPDH were present in both the normal and malignant prostate glands studied. These findings were consistent with in situ and Northern data. The data also shows that the band intensities of laminin 5 chains and α6 integrin were comparable between normal and malignant tissue samples, suggesting that each maintained a low level of synthesis of these chains in vivo at the time of tissue sampling. The interesting exception was the β4 integrin that exhibited consistently higher band intensity than the other cDNAs. These results were substantiated by the dominant intensity of the positive control GAPDH, a ubiquitous housekeeping gene, in each blot. Negative control findings were also significant, because they indicated that data distortion because of nonspecific binding of radiolabeled materials on each blot had minimal effect on sample measurements.

Discussion

Prostate cancer is the most common visceral neoplasm in men, and a major health concern of the aging male population. The mechanism of initiation and progression of this disease is not well understood, but the progression is highly variable and is associated with alterations in the composition of the prostatic extracellular matrix. We have shown previously that the BL circumscribing normal prostate glands differs from the BL surrounding prostate carcinoma. 23,26-28 There seems to be a simultaneous loss of laminin 5, collagen VII, and β4-integrin protein expression in prostate and basal cell carcinoma. 24,28,32-35 These findings suggest that α6β4 integrin expression may be dependent on the presence of its extracellular ligand. The loss of laminin 5 expression may be functionally important for tumor progression in the prostate and could lead to cytoplasmic membrane instability of its integrin receptors α3β1 and α6β4 and altered signaling. 28

This study used four independent techniques to explore the mechanism of loss of laminin 5 expression in the prostate. Immunohistochemistry showed that the protein for the α3 chain of laminin 5 is variably expressed by both normal and neoplastic prostate epithelium. The β3 and γ2 chains, however, were not detected in invasive carcinoma. It is known that the α3 chain can persist by trimer formation with the β1 or β2 and γ1 laminin chains (laminin 6 or 7) in the absence of β3 and γ2, 12 which most likely explains the continuing expression of the α3 chain observed in this study.

Despite the absence of the β3 and γ2 proteins, the carcinoma cells expressed substantial amounts of both messages for these genes. The β3 and γ2 mRNAs were detected by in situ hybridization and Northern analysis, and their presence in neoplastic glands was confirmed using LCM coupled with RNA amplification and reverse Northern analysis. Although we reported that certain prostate cell lines synthesize but fail to secrete individual laminin chains, 36 at that time we did not examine specific laminin 5 chains. Recently, we have shown that LNCaP cells fail to synthesize the β3 chain of laminin 5 (unpublished result). These data suggest that human prostate carcinoma cells exhibit posttranscriptional defect(s) in protein translation of the β3 and γ2 chains of laminin 5.

The loss of laminin 5 is not simply because of the loss of basal cells because the mRNAs for the β4 integrin and the three chains of laminin 5 are made by the carcinoma cells. The loss of laminin 5 is not universal because other tumors continue to express laminin 5 chains. 16-21 Several studies have correlated prognostic significance of laminin 5 γ2 chain expression in tumors. 25,37 Ono and colleagues 25 have shown that laminin 5 γ2 chain expression was a significant factor associated with poor prognosis in squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. The amount of the γ2 chain expressed in pancreatic adenocarcinomas, however, was not associated with the patients’ prognosis. 37 The γ2 chain of laminin 5 has been shown to be up-regulated in gliomas and colonic, gastric, and squamous cell carcinomas. 33 In contrast, decreased expression of the γ2 chain has been observed in other types of carcinomas. 22-24,26,33 The γ2 chain of laminin 5 has in fact been proposed as a marker of increased invasiveness of certain tumor types. 18 The nature of the laminin 5 defect in prostate carcinoma is currently unknown. It is apparent that prostate carcinoma is different from other tumors in which γ2 expression is up-regulated. Whether the loss of γ2 expression in prostate carcinoma explains its slow progression remains to be studied. Invasive prostate cancer creates a new BL and presumably, reestablishes survival signaling contact through α6β1 and other adhesion molecules, which react with the components of the de novo synthesized BL. The nature of these signaling pathways and their effects on gene transcription are unknown but will require further investigation and will possibly reveal new therapeutic applications.

One question addressed by this study is whether or not the loss of protein expression in prostate carcinoma is a posttranscriptional event. Analysis of mRNAs and proteins from carcinoma and adjacent normal glands, supports the idea that constitutive production of mRNA occurs, but with altered translation into protein under conditions of malignancy. The loss of laminin 5 expression in prostate carcinoma apparently is a posttranscriptional event. There are several ways in which translation may be affected including mutations that result in premature stop codons or frame-shifts, or failure of initiation or elongation of protein synthesis. Interestingly, the presence of a defect in an elongation factor in prostate carcinoma has been found, 38,39 suggesting a more general defect in protein translation. Regardless of the mechanism, the altered translation of β3 or γ2 mRNAs into functional proteins contributes to failure of anchoring filament and hemidesmosomal formation. The resulting hemidesmosome loss would predict a less stable epithelial-stromal junction, increased invasion and migration of malignant cells, and disruption of normal integrin signaling pathways.

In summary, protein and mRNA expression of the α3, β3, and γ2 chains of laminin 5 were investigated in normal prostate and invasive prostate carcinoma using immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization, LCM, and Northern and reverse Northern analysis. Protein and mRNA expression of all three laminin 5 chains were detected in the basal cells of normal glands. In contrast, invasive prostate carcinoma showed a loss of β3 and γ2 protein expression with variable expression of α3 chains, but retention of β3 and γ2 mRNAs as detected by in situ hybridization, and Northern and reverse Northern analysis. The loss of laminin 5 protein expression in prostate carcinoma thus seems to be a posttranscriptional event.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jean Barrera for the tissue culture work.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Ray B. Nagle, M.D., Ph.D., Dept. of Pathology, University of Arizona Health Sciences Center, 1501 N. Campbell Ave., Tucson, AZ 85724. E-mail: rnagle@u.arizona.edu.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health grant 2PO1 CA 56666.

J. H. and L. J. contributed equally to this article.

References

- 1.Colognato F, Yurchenco PD: Form and function: the laminin family of heterotrimers. Dev Dyn 2000, 218:213-234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burgeson RE, Chiquet M, Deutzmann, Ekblom P, Engel J, Kleinman H, Martin GR, Meneguzzi G, Paulsson M, Sanes J, Timple R, Tryggvason K, Yamada Y, Yurchenco PD: A new nomenclature for the laminins. Matrix Biol 1994, 14:209-211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koch M, Olson PF, Albus A, Jin W, Hunter DD, Brunken WJ, Burgeson RE, Champliaud MF: Characterization and expression of the laminin γ3 chain: a novel non-basement membrane-associated, laminin chain. J Cell Biol 1999, 145:605-617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patton BL, Miner JH, Chiu AY, Sanes JR: Distribution and function of laminins in the neuromuscular system of developing, adult, and mutant mice. J Cell Biol 1997, 139:1507-1521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferletta M, Ekblom P: Identification of laminin-10/11 as a strong cell adhesive complex for a normal and malignant human epithelial cell line. J Cell Science 1999, 112:1-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Libby RT, Champliaud M-F, Claudepierre T, Xu Y, Gibbons EP, Koch M, Burgeson RE, Hunter DD, Brunken WJ: Laminin expression in adult and developing ketinae: evidence of two novel CNS laminins. J Neurosci 2000, 20:6517-6528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roussele P, Keene DR, Ruggiero F, Champliaud MF, Rest M, Burgeson RE: Laminin 5 binds the NC-1 domain of type VII collagen. J Cell Biol 1997, 138:719-728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xia Y, Gil SG, Carter WG: Anchorage mediated by integrin α6β4 to laminin 5 (epiligrin) regulates tyrosine phosphorylation of a membrane-associated 80-kD protein. J Cell Biol 1996, 132:727-740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giancotti FG: Signal transduction by the α6β4 integrin: charting the path between laminin binding and nuclear events. J Cell Sci 1996, 109:1165-1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter WG, Ryan MC, Gahr PJ: Epiligrin, a new cell adhesion ligand for integrin α3β1 in epithelial basement membranes. Cell 1991, 65:599-610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzales M, Haan K, Baker SE, Fitchmun M, Todorov I, Weitzman S, Jones JCR: A cell signal pathway involving laminin-5, α3β1 integrin, and mitogen-activated protein kinase can regulate epithelial cell proliferation. Mol Biol Cell 1999, 10:259-270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Champliaud MF, Lunstrum GP, Rousselle P, Nishiyama T, Keene DR, Burgeson RE: Human amnion contains a novel laminin variant, laminin 7, which like laminin 6, covalently associates with laminin 5 to promote stable epithelial-stromal attachment. J Cell Biol 1996, 132:1189-1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakano A, Pfendner E, Pulkkinen L, Hashimoto I, Uitto J: Herlitz junctional epidermolysis bullosa: novel and recurrent mutations in the LAMB3 gene and the population carrier frequency. J Invest Dermatol 2000, 115:493-498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uitto J, Pulkkinen L, McLean WHI: Epidermolysis bullosa: a spectrum of clinical phenotypes explained by molecular heterogeneity. Mol Med Today 1997, 3:457-465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verrando P, Blanchet-Bardon C, Pisani A, Thomas L, Cambazard F, Eady RA, Schofield O, Ortonne JP: Monoclonal antibody GB3 defines a widespread defect of several basement membranes and a keratinocyte dysfunction in patients with lethal junctional epidermolysis bullosa. Lab Invest 1991, 64:85-92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyazaki K, Kikkawa Y, Nakamura A, Yasumitsu H, Umeda M: A large cell-adhesive scatter factor secreted by human gastric carcinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993, 90:11767-11771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tani T, Lumme A, Linnala A, Kivilaakso E, Kiviluoto T, Burgeson RE, Kangas L, Leivo I, Virtanen I: Pancreatic carcinomas deposit laminin-5, preferably adhere to laminin-5, and migrate on the newly deposited basement membrane. Am J Pathol 1997, 151:1289-1302 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skyldberg B, Salo S, Eriksson E, Aspenblad U, Moberger B, Tryggvason K, Auer G: Laminin-5 as a marker of invasiveness in cervical lesions. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999, 91:1882-1887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sordat I, Bosman FT, Dorta G, Rousselle P, Aberdam D, Blum AL, Sordat B: Differential expression of laminin-5 subunits and integrin receptors in human colorectal neoplasia. J Pathol 1998, 185:44-52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizushima H, Miyagi Y, Kikkawa Y, Yamanaka N, Yasumitsu H, Misugi K, Miyazaki K: Differential expression of laminin-5/ladsin subunits in human tissues and cancer cell lines and their induction by tumor promoter and growth factors. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1996, 120:1196-1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koshikawa N, Moriyama K, Takamura H, Mizushima H, Nagashima Y, Yanoma S, Miyazaki K: Overexpression of laminin gamma2 chain monomer in invading gastric carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 1999, 59:5596-5601 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin KJ, Kwan C-P, Nagasaki K, Zhang X, O’Hare MJ, Kaelin CM, Burgeson RE, Pardee AB, Sager R: Down-regulation of laminin-5 in breast carcinoma cells. Mol Med 1998, 4:602-613 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hao J, Yang Y, McDaniel KM, Dalkin BL, Cress AE, Nagle RB: Differential expression of laminin 5 (α3β3γ2) by human malignant and normal prostate. Am J Pathol 1996, 149:1341-1349 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Savoia P, Trusolino L, Pepino E, Cremona O, Marchisio PC: Expression and topography of integrins and basement membrane proteins in epidermal carcinomas: basal but not squamous cell carcinomas display loss of α6β4 and BM-600/Nicein. J Invest Dermatol 1993, 101:352-358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ono Y, Nakanishi Y, Ino Y, Niki T, Yamada T, Yoshimura K, Saikawa M, Nakajima T, Hirohashi S: Clinicopathologic significance of laminin-5 γ2 chain expression in squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Cancer 1999, 85:2315-2321 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagle RB, Knox JD, Wolf C, Bowden GT, Cress AE: Adhesion molecules, extracellular matrix, and proteases in prostate carcinoma. J Cell Biochem 1994, 19:S232-S237 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knox JD, Cress AE, Clark V, Manriquez L, Affinito K-S, Dalkin BL, Nagle RB: Differential expression of extracellular matrix molecules and the α6-integrins in the normal and neoplastic prostate. Am J Pathol 1994, 145:167-173 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagle RB, Hao J, Knox JD, Dalkin BL, Clark V, Cress AE: Expression of hemi-desmosomal and extracellular matrix proteins by normal and malignant human prostate tissue. Am J Pathol 1995, 146:1498-1507 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonner RF, Emmert-Buck M, Cole K, Pohida T, Chauaqui R, Goldstein SR, Liotta LA: Laser capture microdissection: molecular analysis of tissue. Science 1997, 278:1481-1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo L, Salunga RC, Guo H, Bittner A, Joy KC, Galindo JE, Xiao H, Rodgers KE, Wan JS, Jackson MR, Erlander MG: Gene expression profiles of laser-captured adjacent neuronal subtypes. Nat Med 1999, 5:117-122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poirier GM-C, Pyati J, Wan JS, Erlander MG: Screening differentially expressed cDNA clones obtained by differential display using amplified RNA. Nucleic Acids Res 1997, 25:913-914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korman NJ, Hrabovsky SL: Basal cell carcinomas display extensive abnormalities in the hemidesmosome anchoring fibril complex. Exp Dermatol 1993, 2:139-144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maatta M, Soini Y, Paakko P, Salo S, Tryggvason K: Autio-Harmainen H: Expression of the laminin gamma2 chain in different histological types of lung carcinoma. A study by immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization. J Pathol 1999, 188:361-368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lazarova Z, Domloge-Hultsch N, Yancey KB: Epiligrin is decreased in papulonodular basal cell carcinoma tumor nest basement membranes and the extracellular matrix of transformed human epithelial cells. Exp Dermatol 1995, 4:121-129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cress AE, Rabinovitz I, Zhu W, Nagle RB: The α6β1 and α6β4 integrins in human prostate cancer progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev 1995, 14:219-228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rabinovitz I, Cress AE, Nagle RB: Biosynthesis and secretion of laminin and S-laminin by human prostate carcinoma cell lines. Prostate 1994, 25:97-107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soini Y, Maatta M, Salo S, Tryggvason K, Autio-Harmainen H: Expression of the laminin γ2 chain in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Pathol 1996, 180:290-294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shen R, Su Z-Z, Olsson CA, Fisher PB: Identification of the human prostate carcinoma oncogene PTI-1 by rapid expression cloning and differential RNA display. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995, 92:6778-6782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun Y, Lin J, Katz AE, Fisher PB: Human prostatic carcinoma oncogene PTI-1 is expressed in human tumor cell line and prostate carcinoma patient blood samples. Cancer Res 1997, 57:18-23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]