Abstract

Choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration is a frequent and poorly treatable cause of vision loss in elderly Caucasians. This choroidal neovascularization has been associated with the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). In current animal models choroidal neovascularization is induced by subretinal injection of growth factors or vectors encoding growth factors such as VEGF, or by disruption of the Bruch’s membrane/retinal pigment epithelium complex with laser treatment. We wished to establish a transgenic murine model of age-related macular degeneration, in which the overexpression of VEGF by the retinal pigment epithelium induces choroidal neovascularization. A construct consisting of a tissue-specific murine retinal pigment epithelium promoter (RPE65 promoter) coupled to murine VEGF164 cDNA with a rabbit β-globin-3′ UTR was introduced into the genome of albino mice. Transgene mRNA was expressed in the retinal pigment epithelium at all ages peaking at 4 months. The expression of VEGF protein was increased in both the retinal pigment epithelium and choroid. An increase of intravascular adherent leukocytes and vessel leakage was observed. Histopathology revealed intrachoroidal neovascularization that did not penetrate through an intact Bruch’s membrane. These results support the hypothesis that additional insults to the integrity of Bruch’s membrane are required to induce growth of choroidal vessels into the subretinal space as seen in age-related macular degeneration. This model may be useful to screen for inhibitors of choroidal vessel growth.

Choroidal neovascularization remains the leading cause of severe vision loss in patients with the exudative form of age-related macular degeneration (ARMD). Choroidal vessels grow through breaks in Bruch’s membrane and proliferate under the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and the sensory retina. The RPE as well as the choriocapillaris are morphologically altered before neovascularization occurs. 1,2 These immature vessels leak serum and blood that can induce a fibrotic reaction known as a disciform scar. Despite recent advances in medical and surgical treatment of choroidal neovascularization the long-term prognosis of ARMD is still poor.

The pathogenesis of exudative ARMD is primarily unknown. Histopathological studies of choroidal neovascular membranes from patients with ARMD have demonstrated the presence of various growth factors that include basic fibroblast growth factor, 3,4 vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), 5-7 and transforming growth factor-β. 3,8 The hypoxia-regulated protein VEGF is one of the major stimulators of angiogenesis. VEGF was first reported in 1983 in highly vascularized tumors. 9 VEGF is secreted as a homodimeric protein that specifically stimulates proliferation of endothelial cells in blood vessels. 10 Five known isoforms with 121 to 206 amino acids are generated from a single gene by alternative mRNA splicing. 11-14 The 165- and 121-kd proteins are commonly expressed in the ischemic retina. 15 Two high-affinity tyrosine kinase transmembrane VEGF receptors, flt-1 and flk-1, are expressed on vascular endothelial cells. 16,17

Recent evidence suggests a central role for VEGF in the development of choroidal neovascularization secondary to ARMD. RPE cells produce VEGF in vivo under physiological conditions, 18 and in vitro after experimental ischemia/reperfusion. 19 In patients with ARMD, high concentrations of VEGF and VEGF receptors were detected in the subfoveal fibrovascular membrane, the surrounding tissue and the RPE. 5,7 In vitro, VEGF mRNA as well as the VEGF protein concentration are increased in RPE cells that were exposed to hypoxia, reactive oxygen species, or cytokines. 19,20

To date, there is no generally accepted experimental in vivo model for choroidal neovascularization that occurs in ARMD. Reproducibility of existing models is limited, partly because of technical artifacts and because the induction of choroidal neovascularization was accompanied by a nonspecific, local inflammatory reaction. 21-27 Recent work reported a transgenic mouse model in which overexpression of VEGF in the photoreceptors was under the control of a constitutively active rhodopsin promoter. These mice developed retinal neovascularization but failed to develop choroidal neovascularization that is characteristic of ARMD. 28 It was hypothesized that the RPE may serve as a barrier that blocks VEGF diffusion from the photoreceptors to the choroid. We sought to determine whether VEGF overexpressed directly in the RPE would overcome this barrier and be sufficient to induce choroidal neovascularization.

Materials and Methods

Unless indicated, reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO.

Generation of Transgenic Mice

A full-length cDNA for murine VEGF164 (a gift from Dr. Yin-Shan Ng and Dr. P. D’Amore) was cloned into the SmaI site of pBluescript II KS. A rabbit β-globin-3′ UTR sequence (a gift from Dr. H. Bujard) was directionally cloned at the 3′ end of the VEGF-coding sequence to add a polyadenylation tail to the transcript to increase mRNA stability. A fragment (−655 to +52) of the cloned 2.8-kb murine RPE65 promoter was directionally cloned into the 5′ end of the VEGF-coding sequence. 29 The sequence of the final construct was confirmed (2,517 bp). The construct sequence was excised and used to generate three founder mice at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Transgenic Mouse Development Facility, University of Alabama at Birmingham. To expand the transgenic lines the founder mice were crossed into a C57BL/6J-TyrC-2J background (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME). Founder no. 1 died without giving offspring, the transgene incorporated in founder no. 2 had a deletion and point mutation. All investigated animals were offspring from founder no. 3 and heterozygous, as they were generated by mating a transgenic parent with a C57BL/6J-TyrC-2J mouse.

Polymerase Chain Reaction

Mice were screened for the presence of the transgene by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of tail DNA. Tail pieces were digested overnight at 56°C in 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 100 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, 5 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 200 mmol/L NaCl, and 30 μl proteinase K at 20 mg/ml. For PCR at 63°C, a 5′ primer (f-RPE65-1, ACC TCG AGG CAA TGG TGA AGA CAG TGA TG), and a 3′ primer (r-exon-1, TGG TGG AGG TAC AGC AGT AA) (Figure 1) ▶ were used to amplify 800 bp of the transgene-specific sequence.

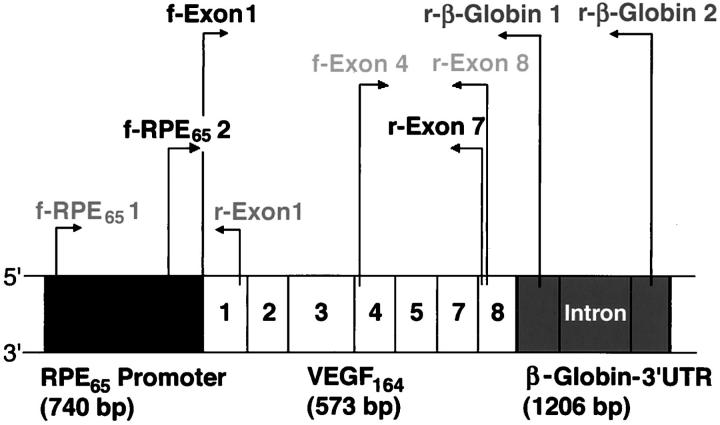

Figure 1.

Scheme of the transgenic construct RPE65/VEGF164/β-globin-3′ UTR (2,517 bp) and location of the primer pairs. The three primer pairs f-RPE65-2 with r-exon-7; and f-exon-4 with r-β-globin-1 or r-β-globin-2 were used for sequencing of the transgenic construct. The primer pair f-RPE65-1 and r-exon-1 was used for PCR amplification of a transgene-specific sequence (800 bp). The primer pair f-exon-4 with r-exon-8 was used in RT-PCR amplification of total VEGF cDNA isoforms, whereas f-RPE6- 2 with r-exon-7 amplified a transgene-specific VEGF164 cDNA sequence (600 bp).

Southern Blot and Sequencing

Offspring were screened for the complete presence of the transgene by Southern blot and sequencing. EcoRI-digested tail DNA (10 μg) was used for Southern blot analysis. Hybridization was performed with α-32-phosphate dCTP (New England Nuclear Life Science Products Inc., Boston, MA)-labeled DNA probe to exon 3 of the VEGF gene for 24 hours at 42°C. After washes (5× SSPE and 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate at room temperature, 1× SSPE and 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate at room temperature, and 0.1× SSPE and 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at 64°C) the Hybond-N+ nucleic acid transfer membrane (Amersham Life Science, Arlington Heights, IL) was autoradiographed (Kodak Scientific Imaging Film Ready Pack, X-OMAT AR; Eastman-Kodak, Rochester, NY).

Sequencing of tail DNA was performed with three sets of primer pairs to cover most of the construct (Figure 1) ▶ : f-RPE65-2 (CTC TAA TCT TCA CTG GAA GCT) with r-exon-7 (CAC ACT TGC AAG TAC GTT CGT), f-exon-1 (CGT CAG AGA GCA ACA TCA TCA CC) with r-β-globin-1 (GGA GAC AAT GGT TGT CAA CA), f-exon 1 with r-β-globin-2 (CTT CCG AGT GAG AGA CAC AA). The PCR product was subcloned into a pCRII-TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and sequenced in a biopolymer facility (Department of Cardiology, Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA).

Veterinary Care and Euthanasia

Mice were housed in a barrier-care facility and fed a diet of animal chow and water ad libitum. Euthanasia was achieved with application of 75 mg/kg of pentobarbital intraperitoneally followed by cervical dislocation. All procedures were performed according to the ARVO guidelines and Children’s Hospital recommendations.

Reverse Transcriptase (RT)-PCR

Whole eyes from postnatal day 15, 1 month-, 2 month-, 4 month-, 5 month-, and 7-month-old mice were analyzed. Total RNA was purified by homogenizing the eyes in RNazol-B (Tel Test Inc., Friendswood, Texas) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was performed with 2 μg of total RNA, oligo (dT) primers (Ambion Inc., Austin, Texas), and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA). The resulting cDNAs were diluted 1:10 and used for subsequent PCR amplification of endogenous VEGF isoforms at 52°C with the primers f-exon-4 (5′ ATC ATG CGG ATC AAA CCT CAC CA) and r-exon-8 (3′ TAC GGA TCC TCC GGA CCC AAA GTG CTC) (Figure 1) ▶ . Amplification of a transgene-specific 600-bp sequence was achieved at 62°C with 5′ f-RPE65-2 and 3′ r-exon-7 primers. Housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) cDNA was amplified with 5′ primer TTA GCA CCC CTG GCC AAG G and 3′ primer CTT ACT CCT TGG AGG CCA TG at 62°C.

In Situ Hybridization

Briefly, a 380-bp transgene sequence spanning exon 4 of VEGF164 and part of the β-globin was cloned into a pCR II-TOPO vector. Antisense and sense probes labeled with digoxigenin-dUTP were generated with the digoxigenin-labeling kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The antisense probe was not specific for transgenic VEGF mRNA but also recognized endogenous VEGF mRNA. Transgenic and control mice eyes fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and paraffin-embedded were hybridized at 55°C overnight in 50% formamide, 0.3 mol/L NaCl, 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8, 5 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 10 mmol/L Na2HPO4, 10% dextran sulfate, 1× Denhardt’s, and 0.5 mg/ml yeast RNA. Washes [5× standard saline citrate (SSC), 2× SSC plus 50% formamide, 2× SSC, and 0.2× SSC] preceded immunohistochemistry with a 1:200 anti-digoxigenin Fab conjugated to alkaline phosphatase and color development with BM purple (all Boehringer Mannheim) for 3 to 5 days at 4°C. Eyes were evaluated under light microscopy.

Screening for Morphological Differences

Routine Harris hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed to screen for morphological differences between control and transgenic mice aged 15 days to 11 months. Briefly, deparaffinized and rehydrated 4- to 5-μm paraffin sections were placed in Harris hematoxylin for 10 minutes at room temperature and rinsed in water. Quick dips in acid alcohol and rinses in tap water preceded quick dips in ammonia water. After rinsing in tap water, the sections were stained for 1 minute at room temperature with eosin followed by dehydration to 100% ethanol and xylene. The sections were mounted in permount.

Furthermore, control and transgenic eye sections were stained with routine periodic acid-Schiff and Gill’s hematoxylin to visualize Bruch’s membrane. Briefly, deparaffinized and rehydrated 4- to 5-μm paraffin sections were incubated with Schiff’s reagent for 6 minutes at room temperature, rinsed 3 × 5 minutes with tap water and incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature in periodic acid solution. After rinses in tap water the sections were stained with Gill’s hematoxylin for 2 minutes at room temperature and developed in ammonia water. The sections were mounted in aquamount.

Immunohistochemistry

Transgenic and littermate control mice were sacrificed and their eyes enucleated. Eyes were embedded in Tissue Tek (Sakura Finetechnical Co, Tokyo, Japan) for frozen sections, or fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Four-μm-thick paraffin sections were cut.

For VEGF immunohistochemistry, frozen sections were fixed in acetone and blocked with 0.1 mol/L phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 2% rabbit serum, 0.3% Triton X-100, and 0.01% sodium azide. Incubation for 1 hour at room temperature with polyclonal goat anti-mouse VEGF (dilution 1:50 in blocking buffer; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was followed by incubation with an affinity-purified polyclonal rabbit anti-goat IgG (diluted 1:200 in blocking solution; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Amplification with 1:100 streptavidin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase for 30 minutes at room temperature preceded color development with diaminobenzidine (DAKO Corp., Carpinteria, CA). Counterstain was performed with Gill’s hematoxylin. Corresponding cross-sections in proximity of the optic nerve entry were evaluated under light microscopy.

CD31 immunohistochemistry was performed on deparaffinized sections. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with 1% H2O2 and antigen retrieval was performed with 0.0036 mg/ml proteinase K in 0.2 mol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5. The tissue was preincubated with TNB-rabbit blocking solution (10% rabbit serum in 0.15 mol/L NaCl, 0.1 mol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 0.5% blocking reagent from a TSA indirect amplification kit (New England Nuclear Life Sciences Technology) for 1 hour at room temperature. The sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C with 1:200 purified anti-mouse CD31 (PECAM-1, MEC13.3; PharMingen, San Diego, CA). A 1:400 dilution of affinity-purified, biotinylated rabbit anti-rat IgG (Vector Laboratories) was applied in TNB-rabbit for 1 hour at room temperature. Signal amplification was obtained with the TSA indirect kit followed by a streptavidin-biotin-alkaline phosphatase complex (ABC Kit; Vector Laboratories). Color development was performed with Fast Red (BioGenex, San Ramon, CA) and counterstain with Gill‘s hematoxylin. Specificity of staining was assessed by omitting the primary antibody. Corresponding choroidal regions with constant retinal thickness were evaluated with a reticule grid at magnification ×1,000 under light microscopy. Choroidal thickness of control and transgenic choroids at the optic nerve entry and 10 μm from the ora serrata was measured in μm in 5 sections each. Statistical analysis of the means was performed with a two-tailed Student’s t-test with unequal variance.

ADPase Staining

Choroidal flatmounts were incubated in 5 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid for 30 minutes at room temperature and fixed in 10% buffered formalin overnight at 4°C. ADPase staining was performed as previously described. 30 Briefly, incubation with a 1:100 dilution of 1 mg/ml ADP in 0.2 mol/L of Tris-maleate, pH 7.2, 3 mmol/L Pb(NO3)2, and 6 mmol/L MgCl2 for 30 minutes at 37°C preceded color development with 2% ammonium sulfide. Flatmounts were inspected under light microscopy. Corresponding areas at equal magnifications of the vortex vein-, the optic nerve-, and the long ciliary artery region were photographed. To determine vessel density, the area of stained vessels relative to the total area was analyzed with NIH image software. Statistical analysis of the values was performed with a two-tailed Student’s t-test with unequal variance.

Lectin Perfusion

Mice were anesthetized with 0.5 ml of avertin intraperitoneally. A thoracotomy exposed the heart and a 20-gauge blunt-ended feeding needle (Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA) was inserted into the left ventricle and fixed with a Dieffenbach Serrefine clamp (Arista). The right atrium was perforated to drain 10 ml of PBS, 10 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde, 5 ml of 1% BSA, and 10 ml of 40 mg/ml fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled Lycopersicon esculentum lectin solution. The eyes were enucleated, prepared as a flatmount, and inspected by fluorescent microscopy.

5-Bromo-2′-Deoxy-Uridine (BrdU) Staining

Mice of the indicated age were injected with 0.25 ml to 0.5 ml of undiluted BrdU (Boehringer Mannheim) intraperitoneally and sacrificed after 1.15 hours. The eyes were enucleated, fixed in 70% ethanol, 0.2 mol/L glycine, pH 2, and processed for 4-μm paraffin sections. Sections were stained according to the BrdU labeling and detection kit II (Boehringer Mannheim) instructions. CD31 and BrdU double stainings were performed before the evaluation of choroidal cell proliferation to establish which cells in the choroid were BrdU-positive. Corresponding cross-sections (n ≥ 7) with equal optic nerve diameter were analyzed by light microscopy with magnification ×800 and the number of stained choroidal cell nuclei was counted. Statistical analysis of the means was performed with a two-tailed Student’s t-test with unequal variance.

Measurement of Blood Vessel Leakage

Choroidal and retinal blood vessel leakage was quantitated in transgenic and control choroids and retinae (n = 6) of 3-month-old mice using Evans blue dye. Evans blue noncovalently binds to plasma albumin in the blood stream (Xu, Quaum, IOVS in print) and in situations of increased vessel leakage is extravasated into the interstitial space. After clearance of Evans blue from the vessel lumina, the amount of extravasated dye is extracted from the interstitial space and quantitated.

Evans blue dye was dissolved in normal saline sonicated for 5 minutes, and filtered through a 5-μm filter. Under deep anesthesia, 30 mg/kg of Evans blue was injected into the tail vein and circulated for 1 hour. The chest cavity was opened and the left ventricle of the heart cannulated. Each mouse was then perfused with citrate-buffered 1% paraformaldehyde, pH 4.2, 37°C for 2 minutes at a physiological pressure of 100 mmHg to clear the dye out of the vessel lumina. Immediately after perfusion, the eyes were enucleated and the retinae and sclera-choroid complex were carefully dissected and collected in separate tubes. After thorough drying (Speed-Vac) of the tissue, the dry weight was measured. Evans blue was extracted by subsequent incubation of the tissue in 75 μl of formamide for 18 hours at 70°C. The extract was ultracentrifuged at a speed of 70,000 rpm for 45 minutes. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured at the absorption maximum for Evans blue in formamide (620 nm) with a spectrophotometer. The dye concentration in the extracts was calculated from a standard curve of Evans blue in formamide and normalized to the dry tissue weight.

CD18 Staining

Choroidal flatmounts were fixed in acetone, permeabilized for 24 hours at room temperature in 1% Triton X-100 in PBS, and blocked with PBS, 3% BSA, and 1% Triton X-100. Biotinylated rat anti-mouse CD18 antibody (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) was incubated at a dilution of 1:100 in PBS, 1% BSA, and 1% Triton X-100 for 24 hours at room temperature, followed by a 1:250 dilution of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated streptavidin (Vector Laboratories) in 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS at room temperature for 24 hours. Staining of leukocytes was evaluated under a fluorescent microscope.

Results

Generation of Transgenic Mice

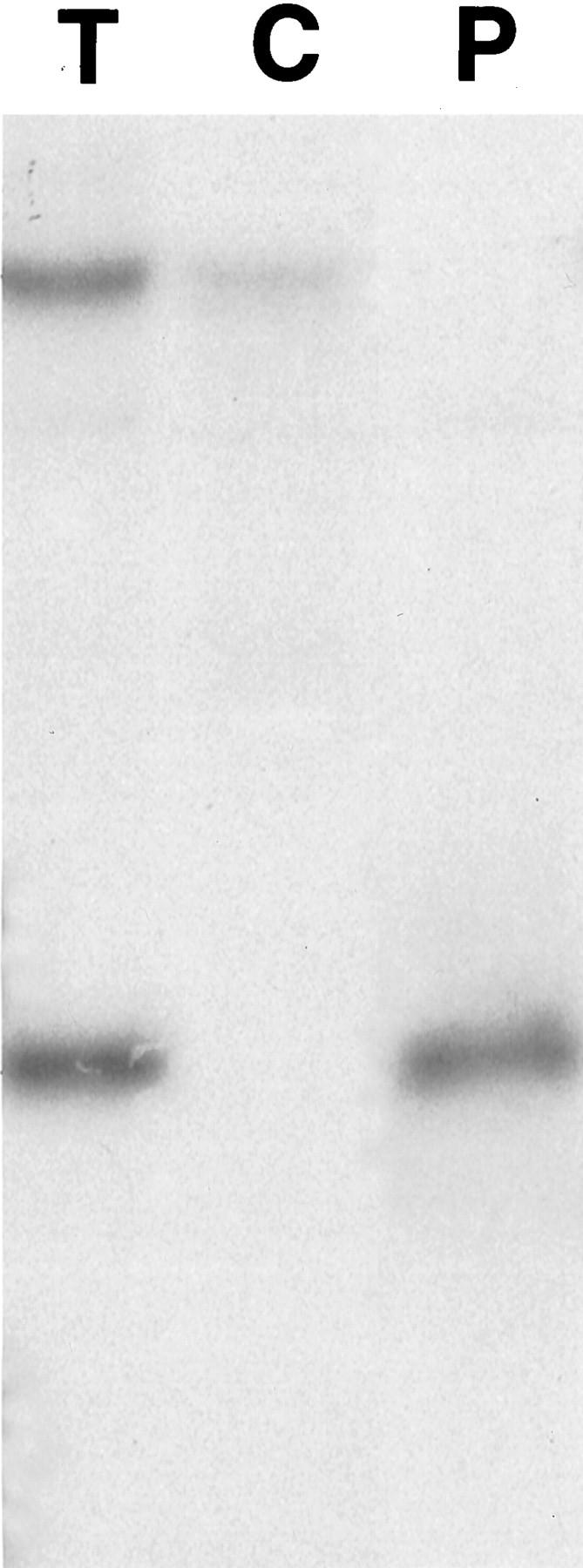

Offspring from line no. 3 mice were generated in a C57BL/SJL background, mated with C57BL/6J-TyrC-2J and expanded by five back-crosses to maintain an albino phenotype. As determined by Southern blot analysis, genomic incorporation of a full copy of the transgene was complete, as both hybridization products for the endogenous VEGF gene (an ∼9-kb band) and for the transgenic VEGF164 gene (a 1,256-bp band) were detected (Figure 2) ▶ . The transgene copy number was ∼2 to 3, as the intensity of the transgene hybridization product was 2–3 stronger than the endogenous hybridization product. Control littermates showed only the endogenous VEGF gene hybridization product. Sequencing of the transgene showed the correct sequence of the complete RPE65/VEGF164/β-globin-3′ UTR construct (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Southern blot analysis of transgenic (T) and control (C) mice tail DNA that was digested with the restriction enzyme EcoRI. A α-32P dCTP-labeled probe to exon 3 of VEGF164 hybridized to the exon 3 sequence of the endogenous VEGF gene (≈9-kb upper band) in all samples. The probe also hybridized to the exon 3 sequence of transgenic VEGF164 in transgenic mice (T) (1,259-bp band). EcoRI digestion of the plasmid (P) that contained the transgenic construct also generated a 1,259 bp band.

The mRNA Expression of the Transgene is Age-Related

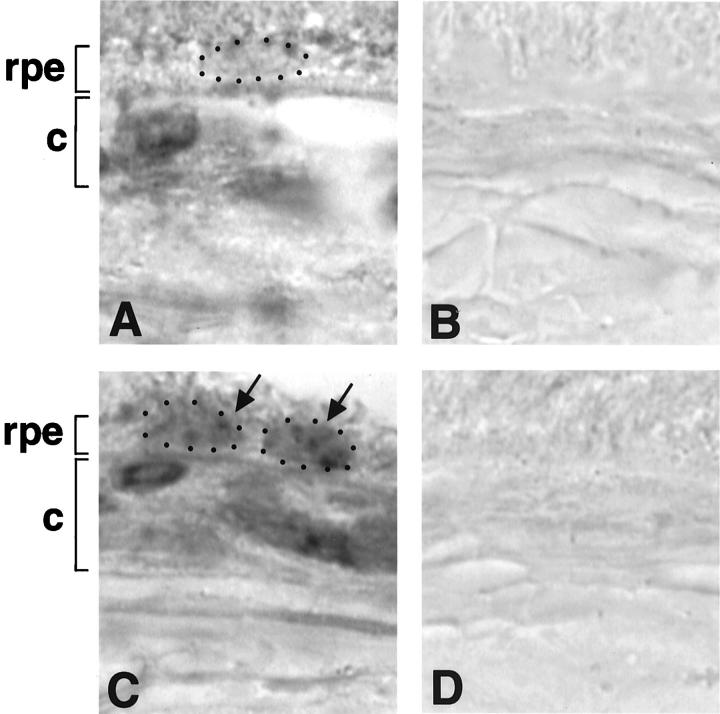

Time course and expression level of transgenic VEGF164 was assessed by RT-PCR and in situ hybridization. In RT-PCR, transgene-specific primers amplified a VEGF164 cDNA-specific 600-bp sequence throughout the life of transgenic mice but not of control mice (Figure 3A) ▶ . Normalized transgenic VEGF164 mRNA increased toward 4 months of age and decreased afterward. GAPDH bands of similar intensity demonstrated equal loading (Figure 3B) ▶ . In situ hybridization with an anti-sense exon 4 to β-globin probe detected endogenous as well as transgenic VEGF164 mRNA. The anti-sense probe showed minimal hybridization product in the RPE cell nuclei of control eye sections (Figure 4A) ▶ , which was markedly increased in the RPE cell nuclei of transgenic eye sections (Figure 4C) ▶ . No difference was seen between the hybridization observed in choroidal cells of transgenic and control eyes. As well, no difference in VEGF mRNA was detected in the inner nuclear or ganglion cell layer of the retina between both groups (data not shown). A sense exon 4 -β-globin probe showed no hybridization (Figure 4, B and D) ▶ .

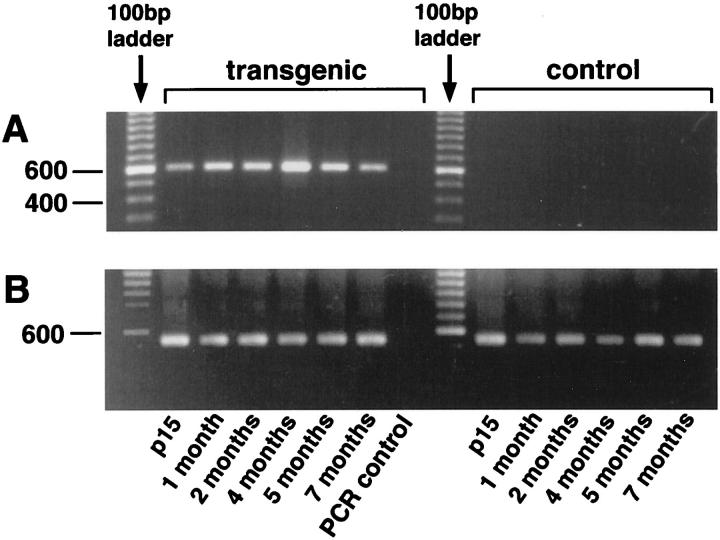

Figure 3.

RT-PCR of transgenic and control whole eyes aged 15 days to 7 months. A: The primer pair f-RPE65-2 with r-exon-7 amplifies transgenic VEGF164 cDNA (≈600 bp) in transgenic eyes at all ages. Control eyes show no amplification product. B: Amplification of the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase (GAPDH). All PCR control reactions are negative.

Figure 4.

In situ hybridization. Original magnification, ×1,600. A: In control eyes, hybridization with an antisense probe demonstrates basal VEGF mRNA expression in the RPE cell nucleus (RPE cell layer, rpe; small dots surround a RPE cell nucleus) and in choroidal cells (choroid, c). B: A sense probe shows no hybridization product. C: In transgenic eyes, hybridization with an antisense probe demonstrates increased hybridization product in RPE cell nuclei and basal VEGF mRNA expression in choroidal cells. D: A sense probe shows no hybridization product.

Expression of VEGF Protein in Transgenic Mouse Choroids

Immunohistochemical staining for VEGF (Figure 5, E and F) ▶ in transgenic mice showed specific and intense staining of RPE cells and choroidal vessels. VEGF immunoreactivity was observed uniformly on the basal side of the RPE cells (Figure 5, E and F ▶ ; inserts). No apical RPE cell and photoreceptor staining could be observed. Choroidal staining was not uniform throughout the eye. Areas of very intense and cluster-like staining alternated with areas of less intense staining. The lamina choriocapillaris showed intense staining, as well as some areas of the lamina vasculosa. In contrast, control choroids were almost free of VEGF staining in the lamina choriocapillaris and vasculosa, and also lacked the cluster-like staining pattern observed in transgenic choroids. The RPE cells of control mice stained uniformly and less intense throughout the eye. In transgenic and control animals comparable retinal staining was observed in ganglion cells and cells of the inner nuclear layer (data not shown). An age-dependent increase of RPE cell and choroidal staining was observed in transgenic animals. This increase was most pronounced at 3 to 4 months of age (data not shown).

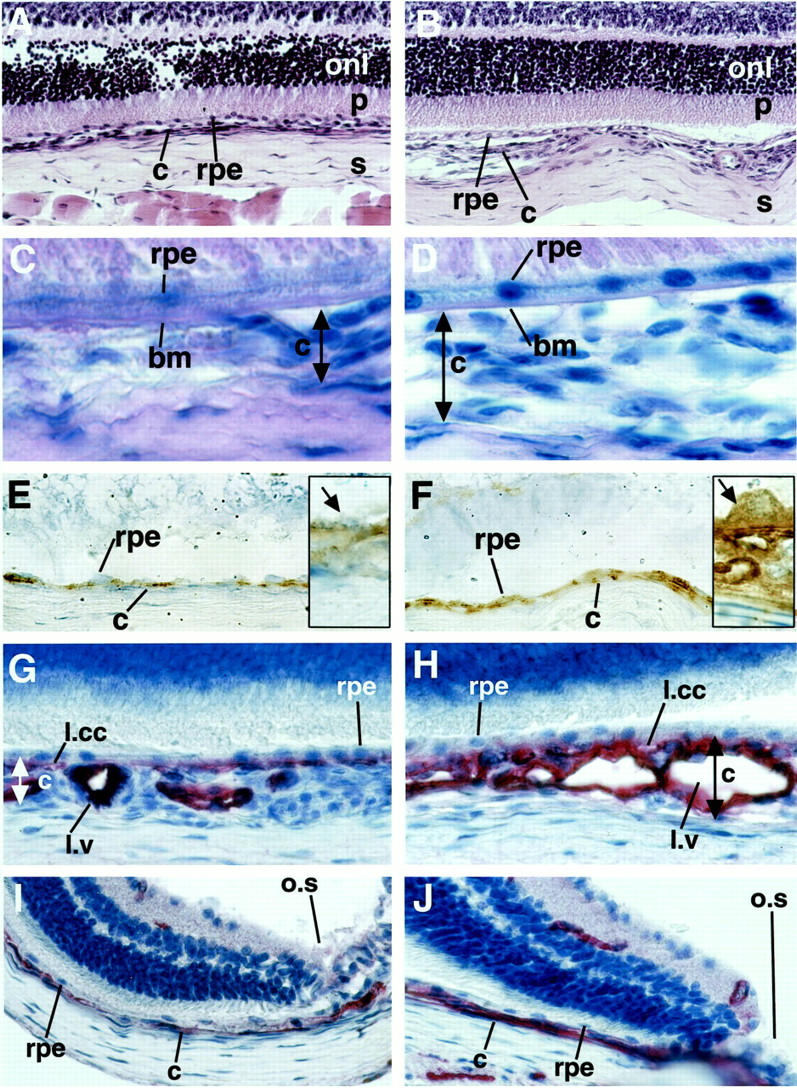

Figure 5.

A and B: Harris hematoxylin (blue) and eosin (pink) staining. Original magnification, ×400. Control (A) and transgenic eye (B) sections demonstrate differences in choroidal (c) architecture underneath the RPE (rpe). No morphological differences are seen in the outer nuclear layer (onl) and the photoreceptor endpieces (p) of the retina. Sclera (s). C and D: PAS (pink) and Gill’s hematoxylin (blue). Original magnification, ×1,000. Control (C) and transgenic (D) eyes show an intact Bruch’s membrane (bm) and no sub-RPE vessels. Limitation of the choroid that was measured is demonstrated by the double-headed arrow. E and F: Immunohistochemistry against VEGF (brown, diaminobenzidine precipitate) in 3-month-old mice counterstained with Gill’s hematoxylin. Original magnifications: ×630, insets ×1,600. E: The control eye shows light VEGF staining in the RPE cell layer and no staining in the choroid. The inset shows a high-power view of VEGF in the RPE cells (arrow). F: Strong VEGF staining is demonstrated in RPE cell layer and the choroid of the transgenic eye. The inset shows a high-power view of an RPE cell with basal secretion of VEGF toward the choroid. G–J: CD31 immunohistochemistry (red, fast red precipitate) in 3-month-old mice counterstained with Gill’s hematoxylin. Original magnification, ×630. Control choroid (G) and transgenic choroid (H) at the optic nerve entry. In the transgenic choroid the lamina choriocapillaris (l.ml) is pronounced and the lamina vasculosa (l.v) thickened because of an increased density of vessels with pronounced lumina because of dilatation. The RPE cell layer is not disrupted. Control choroid (I) and transgenic choroid (J) in proximity of the ora serrata (o.s). The transgenic choroid is thickened.

Choroidal Morphology in Transgenic Mice

Control and transgenic eye sections of mice aged 15 days to 11 months screened by hematoxylin and eosin and by PAS and hematoxylin staining showed differences in the choroid of transgenic mice, which was thickened (Figure 5, A and B) ▶ . In transgenic as well as control eyes the RPE cells and Bruch’s membrane were intact and showed no areas of disruption or damage (Figure 5, C and D) ▶ . In both groups the retina and sclera did not differ.

Immunohistochemistry for the endothelial cell marker CD31 was performed to evaluate the differences in vascularization between transgenic and control choroids of mice aged 15 days to 11 months (Figure 5 ▶ ; G, H, I, and J). Transgenic mice demonstrated a thickened and irregular choroidal vasculature. In some areas the vessels appeared in clusters that bulged toward the sclera. The lamina choriocapillaris stained most intensely. Choriocapillary density was increased and the distance between capillary vessel lumina was reduced. The lamina vasculosa also appeared more dense with dilated vessels and wide lumina. Measurements of total choroidal thickness in standardized areas of the choroid (n = 4 per group) showed a significant increase (P < 0.05) of 35 ± 4% in the optic nerve region and of 40 ± 6% in the proximity of the ora serrata in transgenic animals relative to control mice. Choroidal vessels did not penetrate Bruch’s membrane or appear in the subretinal space at any age. No differences in the retinal vasculature were seen by CD31 immunohistochemistry or by ADPase staining of retinal whole mounts.

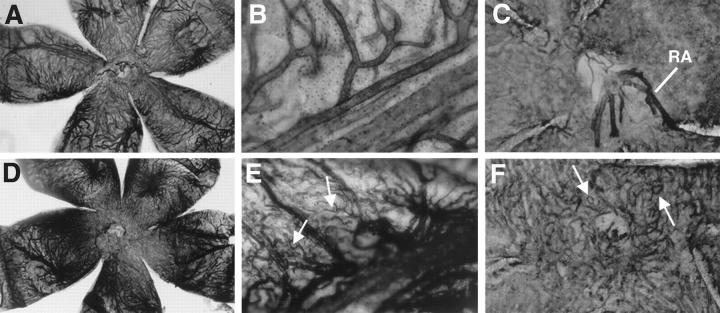

For further evaluation of the choroidal changes observed with CD31 staining, we performed adenosine diphosphatase stains of transgenic and control choroidal flatmounts at 1 to 11 months of age. Choroidal flatmounts of 1- to 2-month-old mice stained poorly (data not shown), whereas choroids of transgenic mice older than 2 months revealed a more intense staining than controls (Figure 6, A and D) ▶ . As already described by Lutty and colleagues, 30 ADPase activity in the retina was most intense in new vessels, which also seems to be the case for new vessels in the choroid of mice. Reaction product was confined almost exclusively to the vasculature, with arteries staining more intense than veins or capillaries as shown before. 30 In transgenic choroids, the regular architecture was perturbed. The vessels appeared elongated and tortuous. Abnormal sprouts were observed and derived particularly from the stem of the long and short ciliary arteries (Figure 6E ▶ relative to 6B). The area of the vortex vein showed an increase in staining intensity and the vessels appeared engorged (data not shown). Choriocapillary vessels around the optic nerve entry also stained intensely, looped, and appeared tortuous (Figure 6F ▶ relative to 6C). Control flatmounts showed very little choriocapillary staining in the area of the optic nerve entry. Vascular density of corresponding flatmount areas was significantly increased in transgenic choroids in respect to control choroids (Figure 7) ▶ .

Figure 6.

ADPase staining of control and transgenic choroidal flatmounts. A: The complete view (original magnification, ×25) of the control choroid shows light vessel staining and normal choroidal architecture. Stem of the long ciliary artery of the control choroid (B) (original magnification, ×400) and optic nerve entry of the control choroid (C). Retinal artery (RA) remnants after dissection. Original magnification, ×250. D: Complete view of the transgenic choroid with strong vessel staining and perturbed vessel architecture. E: Stem of the long ciliary artery of the transgenic choroid with tortuous vessel sprouts (arrows). F: Optic nerve entry of the transgenic choroid. A dense choriocapillary net with looping vessels (arrow) is shown.

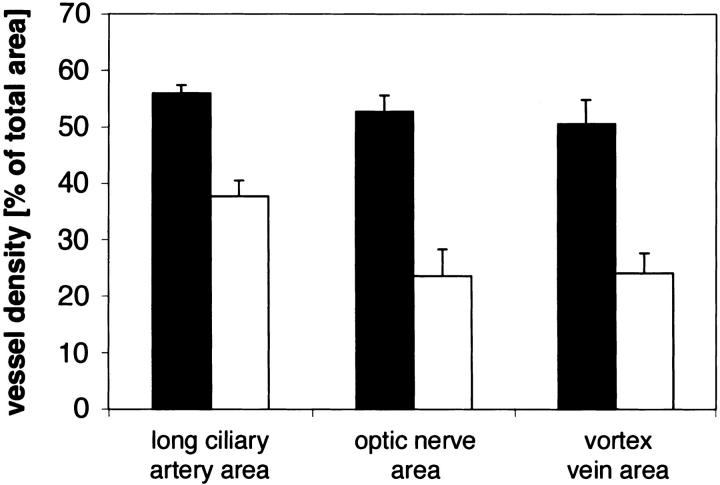

Figure 7.

Histogram of the effect of VEGF overexpression from the RPE on choroidal vessel density per total area. Transgenic choroidal vessel density (black bar) relative to control choroidal vessel density (white bar) as computed with NIH image software of ADPase stainings at corresponding regions and equal magnification. Values are calculated from different flatmounts (n ≥ 4) for each location and are expressed as means ± SEM. The values for transgenic choroidal vessel density are significantly different (P < 0.05) from control values at each location.

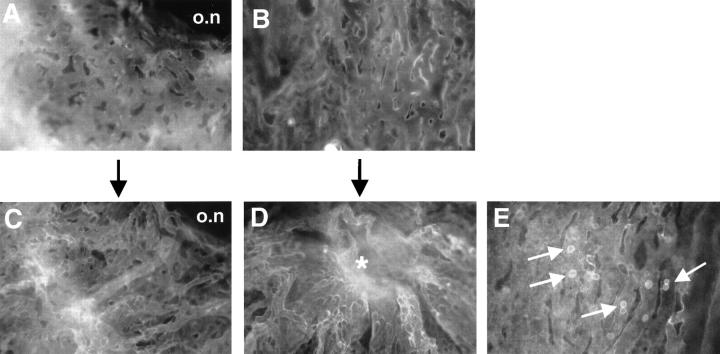

Perfusion of control and transgenic mice with Lycopersicon esculentum lectin was performed to visualize the choriocapillaris (Figure 8) ▶ . Although control choroids showed a normal vascular pattern, the vascular architecture of transgenic choroids was irregular (Figure 8, A and B ▶ versus C and D). Choroidal vessels were denser and engorged with nests of high vascular density with dilated, tortuous, and abnormal vessels. The nests were elevated out of the two dimensional plane of the normal choriocapillaris (Figure 8D) ▶ . Other regions in transgenic choroids were characterized by tortuous vessels that branched off the stem of larger vessels (data not shown), mainly the long ciliary artery. Vessels of the choriocapillaris were denser with only small spaces between the capillaries (Figure 8C ▶ versus 8A). The staining was not as uniform as in control choroids.

Figure 8.

Fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled Lycopersicon esculentum lectin staining of control and transgenic choroidal flatmounts. Original magnification, ×400. A: Choriocapillary network at the optic nerve entry (o.n) of the control choroid. B: Control choriocapillaris at 1 mm from the optic nerve entry shows a two-dimensional structure with few adherent cells (not present here). C: Choriocapillary network at the optic nerve entry of the transgenic choroid. The intercapillary distance is reduced and the vessel architecture perturbed. D: Transgenic choriocapillaris at 1 mm from the optic nerve entry shows nests of dilated and irregularly stained vessels that rise out of the two dimensional focal plane (asterisk). E: Transgenic choriocapillaris with abundant adherent intravascular cells (arrows).

Increased Adherent Leukocytes in Transgenic Choroids

Lectin perfusion revealed cells adherent to the inside of capillaries that were abundant and appeared in clusters of two to four cells in transgenic choroids (Figure 8E) ▶ . The choroidal capillaries were not occluded because of their wide caliber. Only a few adherent cells and no clusters were seen in control choroids. CD18 staining of 3-month-old control and transgenic mice (data not shown) demonstrated that the adherent cells were neutrophils and/or monocytes. These cells were more abundant in transgenic choroids and formed rolls and clusters, whereas control choroids contained only single adherent cells. Flatmounts that were processed without primary CD18 antibody showed no staining.

Evans Blue Leakage in Transgenic Mice

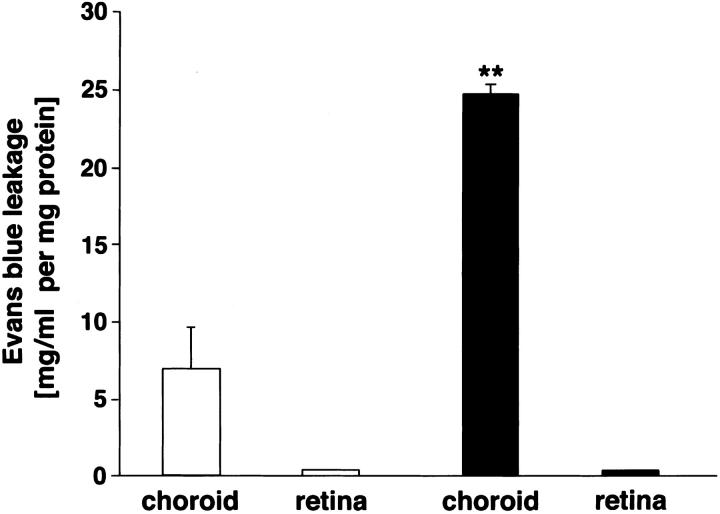

Evans blue vascular leakage was measured in both retina and choroid of transgenic and control eyes. Choroidal leakage was significantly higher (P < 0.001) in the transgenic eyes (24.6 ± 0.7 mg/ml per mg choroidal-scleral tissue) compared to the control eyes (6.9 ± 2.7 mg/ml per mg choroidal-sclera tissue) (Figure 9) ▶ . In the retina, however, transgenic and control eyes did not show differences in Evans blue vessel leakage.

Figure 9.

Histogram of the effect of VEGF overexpression from the RPE on choroidal and retinal vessel leakage in 3-month-old mice. Evans blue leakage in transgenic choroids and retinae (black bars) relative to control choroids and retinae (white bars) normalized for the dry weight of the tissue and expressed as Evans blue concentration in mg/ml per mg protein. Values are calculated as means ± SEM from n = 6. Choroidal vessel Evans blue leakage is significantly different (P < 0.001).

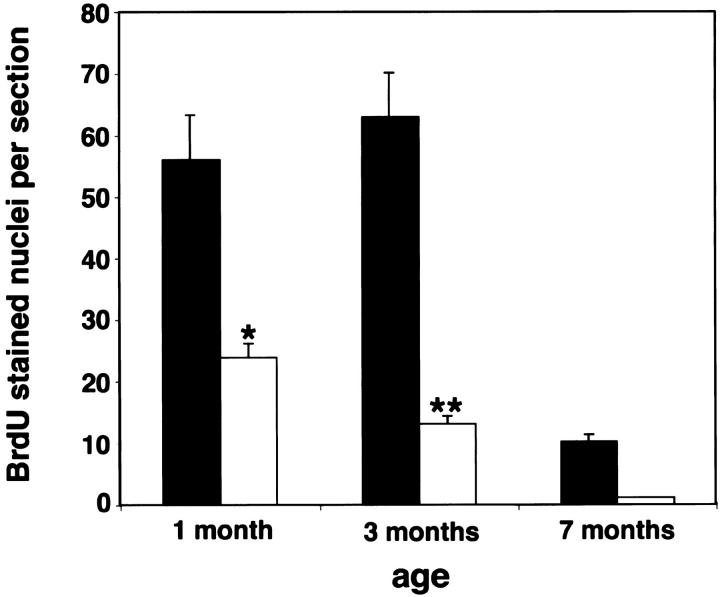

BrdU Staining of Transgenic Mice

BrdU immunohistochemistry was performed to detect abnormal proliferation of choroidal cells in transgenic mice at 1, 3, and 7 months of age. To establish that BrdU was labeling endothelial cells, we first performed CD31 and BrdU double stains and demonstrated that >90% of the BrdU-labeled cells were intraluminal and therefore most likely represented endothelial cells (data not shown). These intraluminal choroidal BrdU-stained nuclei were counted and were found to be increased in transgenic mice at all ages inspected (Figure 10) ▶ . Proliferation peaked at 3 months of age and then subsequently decreased. In contrast, proliferation of choroidal cells in control choroids decreased from birth to nearly undetectable levels at 7 months of age. Transgenic choroids also displayed clusters of more than four proliferating cells that were abundant in central parts of the eye. Toward the ora serrata, control and transgenic choroids showed single cell proliferations (data not shown). BrdU staining was comparable in retina, ciliary body, and cornea of control and transgenic mice as well as in heart, liver, and skin (data not shown).

Figure 10.

Histogram of the effect of VEGF overexpression from the RPE on choroidal cell proliferation. Transgenic choroidal cell number (black bar) relative to control choroidal cell number (white bar) as observed by BrdU staining at specific ages. Values are calculated as means ± SEM from eight choroid eye sections at the optic nerve entry at 1 and 3 months (n ≥ 3) and 7 months (n = 2) of age. Choroidal cell proliferation is significantly different at 1 month (P < 0.05) and 3 months (P < 0.0001).

Discussion

The general effects of increased VEGF on vessel morphology have been previously described. Injection of VEGF into different compartments of the eye of mammals induced neovascularization with dilated and tortuous vessels. 31,32 VEGF has been shown to specifically increase retinal and choroidal endothelial cell proliferation, 33,34 similar to the proliferation of endothelial cells observed by BrdU staining in our model. Surprisingly, intravitreal injection of recombinant human VEGF165 in primates 32 induced capillary closure with ischemia. Our transgenic mice did not show such ischemic changes in their choroidal pathology possibly because of the gradual increase of VEGF in this model. The predominant effect was a marked increase of choroidal density and thickness.

The transgene expression in RPE cells was demonstrated by RT-PCR and in situ hybridization. In situ hybridization showed strong staining against VEGF164 mRNA in the transgenic RPE cell nuclei that was higher than the basal VEGF164 mRNA expression in control RPE cells. Basal VEGF164 mRNA expression was also detected in choroidal cells although the expression was similar in transgenic and control choroids. Because RPE cells and choroidal fibroblasts have been reported to express VEGF mRNA, 18,35 basal VEGF164 mRNA expression may relate to the maintenance of vascular integrity and permeability of the choroid.

The transgenic overexpression of VEGF by the RPE cells resulted in strong staining against VEGF protein in the RPE cells, Bruch‘s membrane, and choroid. VEGF was not detected in the photoreceptor layer in either animal group. This in vivo finding supports that the secretion of VEGF mostly occurs on the basal side of the RPE cell. The polarized VEGF secretion by RPE cells is thought to direct VEGF toward the choroidal vasculature where it may regulate choroidal integrity by binding to the VEGF receptors flt-1 and flk-1/KDR on the adjacent choriocapillaris. 18 In vitro, this polarized secretion of VEGF was reported in human RPE cells in culture. 36

VEGF was originally described as vascular permeability factor (VPF) 37,38 because of its ability to increase microvascular permeability. 38 In normal human eyes, VEGF secreted from the RPE is thought to maintain a fenestrated epithelium in the choriocapillaris. 36 VEGF is increased in diseases associated with increased leakage such as diabetic retinopathy 39,40 and ARMD where it can be detected in the subfoveal fibrovascular membranes. 5 Animal models 41,42 have demonstrated that VEGF is associated with leakage from abnormal vessels. In our model the quantitative measurement of Evans blue leakage from choroidal vessels demonstrated a significant increase in vessel permeability in transgenic choroids in respect to control choroids. In retinal vessels this difference in Evans blue leakage was not observed. We propose that the increased choroidal vessel permeability in our model was a direct effect of increased transgenic VEGF164 secretion that affected choroidal vessel permeability in transgenic choroids.

In lectin perfused flatmounts and CD18 staining of transgenic choroids, an increase of adherent cells was noted in respect to control choroids. Lectins have been described to bind to the surface of adherent intravascular leukocytes 43,44 and CD18 staining identifies neutrophils and monocytes. Histopathology of human specimens of choroidal neovascularization has demonstrated inflammatory cells. 6,45,46 Most animal models of choroidal and subretinal neovascularization induce a significant extravascular inflammatory response that is regarded as secondary to the mechanical disruption of the retina or choroid. However, VEGF in our model induces an intravascular adherence of leukocytes without preceding mechanical disruption. This finding is in accordance with another transgenic mouse model in which VEGF was overexpressed in epidermal keratinocytes. Overexpression in keratinocytes resulted in an increase in intravascular leukocyte adhesion in postcapillary skin venules. 41 VEGF has also been shown to increase leukocyte adherence in early angiogenesis by up-regulation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1). 47-50 ICAM-1 mediated the invasion of leukocytes in corneal angiogenesis in vivo 47 and in the retinal vasculature. 49 We suspect that the observed leukostasis in our transgenic mice is induced by a VEGF-mediated up-regulation of ICAM-1.

The paracrine secretion of VEGF into the choriocapillaris with subsequent choroidal neovascularization did not result in a disruption of the Bruch’s membrane/RPE cell complex and subsequent subretinal neovascularization, as seen in ARMD. Subretinal neovascularization can be induced in animals by introducing growth factors including basic fibroblast growth factor and VEGF into the subretinal space, or by laser disruption of the Bruch’s membrane/RPE complex. 21,22,27,31,51,52 However these models are associated with significant extravascular inflammation and/or tissue disruption that may be permissive to subretinal extension of the choroidal neovascularization. Clinical disorders with breaks in Bruch‘s membrane such as myopia, trauma, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, and histoplasmosis have an increased incidence of choroidal neovascularization. Therefore our model reinforces the idea that an intact Bruch’s membrane/RPE barrier prevents choroidal neovascularization from penetrating into the subretinal space.

In summary, the present work establishes a transgenic mouse model in which overexpression of VEGF in RPE cells is sufficient for the development of intrachoroidal neovascularization. Our model is not complicated by technical artifacts and demonstrates that transgenic overexpression of VEGF from the intact RPE is not sufficient to induce subretinal neovascularization. Because degeneration of RPE cells and Bruch’s membrane is a common morphological feature in human ARMD, we suggest that breaks in this barrier are necessary in the progression of disease in humans. Finally we propose that this new model can be used to study agents that may inhibit choroidal neovascularization.

Acknowledgments

We thank Taturo Udagawa for useful and critical discussions; Richard Sullivan, Diane Sanchez-Bielenberg, Evelyn Flynn, and Gerald Lutty for their advice in establishing many techniques; and Kristin Gullage and Joey Fox for photography.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Robert J. D’Amato, M.D., Ph.D., Enders Building 1006, Children‘s Hospital, 300 Longwood Ave., Boston, Massachusetts, 02115. E-mail: robert.damato@tch.harvard.edu.

Supported by the American Health Assistance Foundation No. M2000020, and Gottlieb Daimler and Karl Benz Foundation, project number 02-18/99.

References

- 1.Adamis AP, Shima DT, Yeo KT, Yeo TK, Brown LF, Berse B, D’Amore PA, Folkman J: Synthesis and secretion of vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor by human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1993, 193:631-638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lutty G, Grunwald J, Majji AB, Uyama M, Yoneya S: Changes in choriocapillaris and retinal pigment epithelium in age-related macular degeneration. Mol Vis 1999, 5:35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amin R, Puklin JE, Frank RN: Growth factor localization in choroidal neovascular membranes of age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1994, 35:3178-3188 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frank RN, Amin RH, Eliott D, Puklin JE, Abrams GW: Basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor are present in epiretinal and choroidal neovascular membranes. Am J Ophthalmol 1996, 122:393-403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kvanta A, Algvere PV, Berglin L, Seregard S: Subfoveal fibrovascular membranes in age-related macular degeneration express vascular endothelial growth factor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1996, 37:1929-1934 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez PF, Sippy BD, Lambert HM, Thach AB, Hinton DR: Transdifferentiated retinal pigment epithelial cells are immunoreactive for vascular endothelial growth factor in surgically excised age-related macular degeneration-related choroidal neovascular membranes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1996, 37:855-868 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kliffen M, Sharma HS, Mooy CM, Kerkvliet S, de Jong PT: Increased expression of angiogenic growth factors in age-related maculopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 1997, 81:154-162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy VM, Zamora RL, Kaplan HJ: Distribution of growth factors in subfoveal neovascular membranes in age-related macular degeneration and presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1995, 120:291-301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Senger DR, Galli SJ, Dvorak AM, Perruzzi CA, Harvey VS, Dvorak HF: Tumor cells secrete a vascular permeability factor that promotes accumulation of ascites fluid. Science 1983, 219:983-985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leung DW, Cachianes G, Kuang WJ, Goeddel DV, Ferrara N: Vascular endothelial growth factor is a secreted angiogenic mitogen. Science 1989, 246:1306-1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrara N, Houck KA, Jakeman LB, Winer J, Leung DW: The vascular endothelial growth factor family of polypeptides. J Cell Biochem 1991, 47:211-218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klagsbrun M, D’Amore PA: Vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 1996, 7:259-270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veikkola T, Alitalo K: VEGFs, receptors and angiogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol 1999, 9:211-220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poltorak Z, Cohen T, Neufeld G: The VEGF splice variants: properties, receptors, and usage for the treatment of ischemic diseases [In Process Citation]. Herz 2000, 25:126-129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shima DT, Gougos A, Miller JW, Tolentino M, Robinson G, Adamis AP, D’Amore PA: Cloning and mRNA expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in ischemic retinas of Macaca fascicularis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1996, 37:1334-1340 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Vries C, Escobedo JA, Ueno H, Houck K, Ferrara N, Williams LT: The fms-like tyrosine kinase, a receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor. Science 1992, 255:989-991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terman BI, Dougher-Vermazen M, Carrion ME, Dimitrov D, Armellino DC, Gospodarowicz D, Bohlen P: Identification of the KDR tyrosine kinase as a receptor for vascular endothelial cell growth factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1992, 187:1579-1586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim I, Ryan AM, Rohan R, Amano S, Agular S, Miller JW, Adamis AP: Constitutive expression of VEGF, VEGFR-1, and VEGFR-2 in normal eyes [published erratum appears in Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2000 Feb;41: 368]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1999, 40:2115-2121 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuroki M, Voest EE, Amano S, Beerepoot LV, Takashima S, Tolentino M, Kim RY, Rohan RM, Colby KA, Yeo KT, Adamis AP: Reactive oxygen intermediates increase vascular endothelial growth factor expression in vitro and in vivo. J Clin Invest 1996, 98:1667-1675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Punglia RS, Lu M, Hsu J, Kuroki M, Tolentino MJ, Keough K, Levy AP, Levy NS, Goldberg MA, D’Amato RJ, Adamis AP: Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression by insulin-like growth factor I. Diabetes 1997, 46:1619-1626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soubrane G, Cohen SY, Delayre T, Tassin J, Hartmann MP, Coscas GJ, Courtois Y, Jeanny JC: Basic fibroblast growth factor experimentally induced choroidal angiogenesis in the minipig. Curr Eye Res 1994, 13:183-195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimura H, Sakamoto T, Hinton DR, Spee C, Ogura Y, Tabata Y, Ikada Y, Ryan SJ: A new model of subretinal neovascularization in the rabbit. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1995, 36:2110-2119 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orzalesi N, Migliavacca L, Miglior S: Subretinal neovascularization after naphthalene damage to the rabbit retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1994, 35:696-705 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pollack A, Korte GE, Weitzner AL, Henkind P: Ultrastructure of Bruch’s membrane after krypton laser photocoagulation. I. Breakdown of Bruch’s membrane. Arch Ophthalmol 1986, 104:1372-1376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pollack A, Korte GE, Heriot WJ, Henkind P: Ultrastructure of Bruch’s membrane after krypton laser photocoagulation. II. Repair of Bruch’s membrane and the role of macrophages. Arch Ophthalmol 1986, 104:1377-1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lutty GA, McLeod DS, Pachnis A, Costantini F, Fabry ME, Nagel RL: Retinal and choroidal neovascularization in a transgenic mouse model of sickle cell disease. Am J Pathol 1994, 145:490-497 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spilsbury K, Garrett KL, Shen WY, Constable IJ, Rakoczy PE: Overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the retinal pigment epithelium leads to the development of choroidal neovascularization. Am J Pathol 2000, 157:135-144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okamoto N, Tobe T, Hackett SF, Ozaki H, Vinores MA, LaRochelle W, Zack DJ, Campochiaro PA: Transgenic mice with increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in the retina: a new model of intraretinal and subretinal neovascularization [see comments]. Am J Pathol 1997, 151:281-291 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boulanger A, Liu S, Henningsgaard AA, Yu S, Redmond TM: The upstream region of the RPE65 gene confers retinal pigment epithelium-specific expression in vivo and in vitro and contains critical octamer and E-box sites. J Biol Chem 2000, 275:31274-31282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lutty GA, McLeod DS: A new technique for visualization of the human retinal vasculature. Arch Ophthalmol 1992, 110:267-276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ozaki H, Hayashi H, Vinores SA, Moromizato Y, Campochiaro PA, Oshima K: Intravitreal sustained release of VEGF causes retinal neovascularization in rabbits and breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier in rabbits and primates. Exp Eye Res 1997, 64:505-517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tolentino MJ, Miller JW, Gragoudas ES, Chatzistefanou K, Ferrara N, Adamis AP: Vascular endothelial growth factor is sufficient to produce iris neovascularization and neovascular glaucoma in a nonhuman primate. Arch Ophthalmol 1996, 114:964-970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tolentino MJ, Miller JW, Gragoudas ES, Jakobiec FA, Flynn E, Chatzistefanou K, Ferrara N, Adamis AP: Intravitreous injections of vascular endothelial growth factor produce retinal ischemia and microangiopathy in an adult primate. Ophthalmology 1996, 103:1820-1828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li W, He Z, Li Y, Yanoff M: Vascular endothelial growth factor regulates both apoptosis and angiogenesis of choriocapillaris endothelial cells. Microvasc Res 2000, 59:286-289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kvanta A: Expression and regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor in choroidal fibroblasts. Curr Eye Res 1995, 14:1015-1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blaauwgeers HG, Holtkamp GM, Rutten H, Witmer AN, Koolwijk P, Partanen TA, Alitalo K, Kroon ME, Kijlstra A, van Hinsbergh VW, Schlingemann RO: Polarized vascular endothelial growth factor secretion by human retinal pigment epithelium and localization of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors on the inner choriocapillaris. Evidence for a trophic paracrine relation. Am J Pathol 1999, 155:421-428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Senger DR, Perruzzi CA, Feder J, Dvorak HF: A highly conserved vascular permeability factor secreted by a variety of human and rodent tumor cell lines. Cancer Res 1986, 46:5629-5632 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts WG, Palade GE: Increased microvascular permeability and endothelial fenestration induced by vascular endothelial growth factor. J Cell Sci 1995, 108:2369-2379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murata T, Nakagawa K, Khalil A, Ishibashi T, Inomata H, Sueishi K: The relation between expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier in diabetic rat retinas. Lab Invest 1996, 74:819-825 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mathews MK, Merges C, McLeod DS, Lutty GA: Vascular endothelial growth factor and vascular permeability changes in human diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1997, 38:2729-2741 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Detmar M, Brown LF, Schon MP, Elicker BM, Velasco P, Richard L, Fukumura D, Monsky W, Claffey KP, Jain RK: Increased microvascular density and enhanced leukocyte rolling and adhesion in the skin of VEGF transgenic mice. J Invest Dermatol 1998, 111:1-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thurston G, Suri C, Smith K, McClain J, Sato TN, Yancopoulos GD, McDonald DM: Leakage-resistant blood vessels in mice transgenically overexpressing angiopoietin-1. Science 1999, 286:2511-2514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thurston G, Baluk P, Hirata A, McDonald DM: Permeability-related changes revealed at endothelial cell borders in inflamed venules by lectin binding. Am J Physiol 1996, 271:H2547-H2562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thurston G, Murphy TJ, Baluk P, Lindsey JR, McDonald DM: Angiogenesis in mice with chronic airway inflammation: strain-dependent differences [see comments]. Am J Pathol 1998, 153:1099-1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lopez PF, Grossniklaus HE, Lambert HM, Aaberg TM, Capone A, Jr, Sternberg P, Jr, L’Hernault N: Pathologic features of surgically excised subretinal neovascular membranes in age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol 1991, 112:647-656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seregard S, Algvere PV, Berglin L: Immunohistochemical characterization of surgically removed subfoveal fibrovascular membranes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1994, 232:325-329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Becker MD, Kruse FE, Azzam L, Nobiling R, Reichling J, Volcker HE: In vivo significance of ICAM-1-dependent leukocyte adhesion in early corneal angiogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1999, 40:612-618 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Melder RJ, Koenig GC, Witwer BP, Safabakhsh N, Munn LL, Jain RK: During angiogenesis, vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor regulate natural killer cell adhesion to tumor endothelium [see comments]. Nat Med 1996, 2:992-997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lu M, Perez VL, Ma N, Miyamoto K, Peng HB, Liao JK, Adamis AP: VEGF increases retinal vascular ICAM-1 expression in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1999, 40:1808-1812 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miyamoto K, Khosrof S, Bursell SE, Moromizato Y, Aiello LP, Ogura Y, Adamis AP: Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-induced retinal vascular permeability is mediated by intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1). Am J Pathol 2000, 156:1733-1739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dobi ET, Puliafito CA, Destro M: A new model of experimental choroidal neovascularization in the rat. Arch Ophthalmol 1989, 107:264-269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Frank RN, Das A, Weber ML: A model of subretinal neovascularization in the pigmented rat. Curr Eye Res 1989, 8:239-247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]