Abstract

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which is often produced at high levels by tumor cells, is a well-known mediator of tumor angiogenesis. VEGF receptor tyrosine kinases, KDR/Flk-1 and Flt-1, have been thought to be expressed exclusively by endothelial cells. In this study, we have used a prostate tumor progression series comprised of a differentiated rat prostate epithelial cell line, NbE-1, and its highly motile clonal derivative, FB2. Injection of NbE-1 cells into the inferior vena cava of syngeneic rats indicated that these cells are nontumorigenic. Using the same model, FB2 cells generated rapidly growing and well-vascularized tumors in the lungs. NbE-1 expressed marginal levels of VEGF, whereas high levels of VEGF protein were detected in FB2-conditioned medium and in FB2 tumors in vivo. Analysis of 125I-VEGF165 binding to NbE-1 and FB2 cells indicated that only motile FB2 cells expressed the VEGF receptor Flt-1. Consistent with this finding, physiological concentrations of VEGF induced chemotactic migration in FB2 but not in NbE-1 cells. This is the first documentation of a functional Flt-1 receptor in prostate tumor cells. Our results suggest two roles for VEGF in tumor progression: a paracrine role as an angiogenic factor and a previously undescribed role as an autocrine mediator of tumor cell motility.

The growth of a tumor is dependent on its blood supply and cancer cells can induce the formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing ones through a process called angiogenesis. 1,2 In some circumstances, tumor vascularization may also occur by de novo organization of new blood capillaries, a distinct process termed vasculogenesis. 3-6 Under normal conditions, angiogenesis plays an important physiological role in tissue remodeling in the female reproductive system, during embryonic development and in wound healing. 7,8 In addition to cancer, pathological angiogenesis is also associated with other clinical conditions such as diabetic retinopathy, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis. 9

The discovery of angiogenesis-dependent tumor growth led to the identification of several endothelial cell (EC) growth factors, including acidic and basic fibroblast growth factors, vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF), transforming growth factor-α, platelet-derived growth factor, and angiopoietin. 5,9,10 VEGF, also known as vascular permeability growth factor, is a chemoattractant and mitogen for ECs in vitro. 11,12 Many studies have documented the important role of VEGF as a mediator of angiogenesis in vivo. Monoallelic loss of the VEGF locus in the mouse results in embryonic lethality arising from defective vascularization. VEGF expression is required for the repetitive angiogenic cycles associated with expansion of the endometrium and during ovulation. 13 High levels of VEGF are produced by various types of tumors but levels in normal, nonvessel-forming tissues are generally low, 14,15 consistent with the requirement for sustained vascular remodeling during tumor growth. Studies in which tumor-bearing mice were treated with anti-VEGF antibodies or soluble VEGF receptor proteins demonstrated dramatic reductions in tumor size. 16-19 Targeted disruption of VEGF or VEGF receptor genes results in impaired blood vessel formation, growth retardation, and embryonic death. 20,21

VEGF binds to two high-affinity tyrosine kinase receptors, Flt-1 and KDR/Flk-1 (human/mouse homologs), 22-24 which are expressed primarily by ECs. Although linked to ECs and vascular function in a variety of studies, the specific roles of the two VEGF receptor kinases are not clearly defined. Both receptors are phosphorylated in response to VEGF and are capable of initiating a cellular signaling cascade. 25,26 In ECs, KDR/Flk-1 seems to be the major transducer of VEGF activities, such as mitogenicity, actin reorganization, and gross morphological changes. 25 Although ablation of the flt-1 gene results in an embryonic lethal phenotype because of poor vascularization, this defect arises not from an inability of flt-1(−/−) ECs to form vessels, but from an overproduction of EC precursors, 27 suggesting a specialized role for Flt-1 in negative control of EC proliferation.

Observations made by other investigators and by us demonstrated that VEGF receptor expression is not always restricted to ECs and is sometimes a property of tumor cells. Flt-1 is expressed by monocytes and KDR/Flk-1 is found on BALB/c 3T3 cells. 28,29 Different lines of melanoma were also shown to express Flt-1 or KDR/Flk-1. 30-32 Soker and colleagues 33 recently cloned a third VEGF receptor, neuropilin-1 (NRP-1), from breast carcinoma. This receptor is expressed by a variety of tumor cell lines including melanomas and prostate carcinomas. In ECs, NRP-1 expression enhances VEGF-mediated migration and it probably serves as a co-receptor for KDR/Flk-1.

Increased angiogenic activity, based on microvessel density counts of preserved tissues, has been linked to a more aggressive phenotype in studies of human prostate cancer. 34-37 High levels of VEGF have been observed in aggressive variants of the LNCaP human prostate cancer line in comparison to less malignant variants in the same cell lineage. 38 Increased levels of VEGF were also identified specifically in patients with metastatic prostate cancer in comparison to prostate cancer patients with localized disease. 39 These observations indicate that increased production of VEGF may be associated specifically with the emergence of an aggressive phenotype in prostate cancer progression. Studies in model systems have shown that high levels of VEGF are likely to promote angiogenesis through paracrine mediation of EC migration and proliferation. However, two separate studies of prostate carcinoma have recently shown that Flt-1 could be immunolocalized to carcinoma cells in 100% of the specimens evaluated. 40,41 Flt-1 was also expressed in benign areas adjacent to the tumors. These findings suggest the possibility that tumor cell-derived VEGF might play an autocrine role in prostate cancer spread in addition to its known paracrine activity.

We previously generated a rat prostate epithelial cell lineage comprised of stable cell lines representing the transition from low to high motility as seen with metastatic prostate tumors. 42 The NbE-1 parent cell line expresses a barrier-forming epithelial morphology and low intrinsic motility, although an invasive, spontaneously-arising variant, the NbMC-2/FB2 subline (hereafter FB2), exhibits no barrier-forming properties and high chemokinetic motility. Motile properties in vitro often correlate with a malignant phenotype in vivo and cell motility is functionally an important component of tumor metastasis. In this study we examined the tumorigenic activity of these lines in vitro and in vivo. Injection of NbE-1 and FB2 into the inferior vena cava of syngeneic rats indicated that NbE-1 cells were nontumorigenic, whereas FB2 cells generated rapidly growing, well-vascularized tumors in the lungs. Examination of VEGF production by the cells revealed that NbE-1 expressed very low levels whereas FB2 cells secreted large amounts of VEGF in vitro and in vivo. Subsequently, we observed that FB2, but not NbE-1 cells, expressed VEGF receptors that were further identified as Flt-1. Accordingly, we have shown that VEGF can induce chemotactic migration in FB2 but not in NbE-1 cells. Our results suggest two roles for VEGF in tumor progression: a paracrine role as an angiogenic factor and an autocrine mediator of tumor cell motility.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture media, enzymes for reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), PCR primers, and agarose were purchased from Life Technologies (Rockville, MD). Human recombinant VEGF165 was produced in sf-21 insect cells and iodinated as described. 31 Anti-Flk-1 and anti-Flt-1 antibodies were purchased from Santa-Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-factor VIII antibodies were purchased from DAKO Corporation (Carpinteria, CA). Anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). Vectastain ABC kit was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). Polystyrene microspheres were purchased from Polysciences (Warrington, PA). 125I-Sodium, 32P-dCTP, GeneScreen-Plus hybridization transfer membrane, and Western blot chemiluminescence reagent were purchased from DuPont New England Nuclear Research Products (Boston, MA). Disuccinimidyl suberate and Iodo-beads were purchased from Pierce Chemical Co. (Rockford, IL). Heparin Sepharose and protein G Sepharose were purchased from Pharmacia LKB Biotechnology Inc. (Piscataway, NJ). RNAzol-B was purchased from Tel-test Inc. (Friendswood, TX). Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) buffers and polyvinylidene difluoride membranes were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). Polyvinylpyrrolidine-free filters were purchased from Nucleopore Corp. (Pleasanton, CA). Molecular weight marker was purchased from Amersham (Arlington Heights, IL). X-ray films were purchased from Eastman Kodak (Rochester, NY). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), unless otherwise mentioned.

Cell Culture and Tumor Growth in Vivo

NbE-1 and FB2 cells were maintained in 4:1 DMEM:Ham’s F12 (T media) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics. Cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. NbE-1 and FB2 cells were grown to 80% confluence, trypsinized, and resuspended in serum-free T media. A single-cell suspension inoculum of 1 × 10 7 cells was injected into the inferior vena cava of 5-week-old NBL/CRX (Noble) rats (n = 6 animals for each cell line). Animals were sacrificed at 4 weeks and lung samples were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, and then sectioned (5-μm thickness). The extent of lung parenchyma replaced by tumor cells was determined by measuring the average surface area taken up by the tumor in five respective lung fields in the histological sections. This was determined using NIH image software. All animal experiments were performed according to Children’s Hospital animal resources (ARCH) guidelines.

Immunostaining

Serial sections were immunostained with anti-VEGF, Flt-1, and Factor VIII antibodies. To test staining specificity, the primary antibody was replaced by rabbit IgG in the control sections. The primary antibodies were detected by the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex method and positive staining in brown was obtained by the diaminobenzidine method (Vector Laboratories). The slides were counter-stained with methyl green to visualize the cell nuclei. Stained sections were photographed, scanned, and images were processed using Photoshop software.

RNA and Protein Analyses

Total RNA was prepared from cells in culture using RNAzol according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA (2 μg) was used to prepare cDNA using RT. Primers specific for human VEGF, rat Flt-1, rat Flk-1, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase cDNA sequences were used for the PCR. Amplified DNA was separated on a 1.5% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. Samples of 20 μg RNA were separated on a 1% formaldehyde-agarose gel, and transferred to a GeneScreen-Plus membrane. The membrane was hybridized with a 32P-labeled human VEGF165 cDNA at 63°C for 18 hours. The membrane was washed and exposed to X-ray film. VEGF protein was purified form the conditioned media of FB2 cells using heparin-Sepharose chromatography as previously described. 31 Protein samples were electrophoresed through 12% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, blotted onto a membrane, and probed with anti-VEGF antibodies (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The antibodies were detected by anti-rabbit IgG antibodies conjugated to peroxidase. The membrane was developed using chemiluminescence reagent and exposed to X-ray film.

125I-VEGF Cross-Linking and Immunoprecipitation of Labeled Complexes

Cross-linking experiments using 125I-VEGF165 were performed as previously described. 31 125I-VEGF165 cross linked complexes were resolved by 6% SDS/PAGE and the gels were exposed to an X-ray film. For immunoprecipitation experiments, samples of the cell lysate containing 125I-VEGF165/receptor complexes were incubated with anti-Flt-1 and anti-Flk-1 antibodies for 12 hours at 4°C. Protein G Sepharose beads were added and the incubation continued for 30 minutes. The beads were washed three times with lysis buffer, boiled in reducing sample buffer, and bound proteins were resolved by 6% SDS/PAGE. The gels were dried and exposed to X-ray film.

Motility and Proliferation Assays

A modification of the phagokinetic track assay was previously described. 42 NbE-1 and FB2 cells were seeded on polystyrene microsphere-coated dishes at a density of 4000 cells/cm2. Cultures were observed and photographed 2 and 4 days after plating. Migration assays were performed in Boyden chambers (Neuro Probe Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). Polyvinylpyrrolidine-free filters were coated for 15 minutes with fibronectin (Sigma) diluted in phosphate-buffered saline to a final concentration of 25 μg/ml. After 2 hours of drying, the coated filter was placed on a 48-blind well chamber containing varying concentrations of VEGF diluted in T media supplemented with 1% FBS. After trypsinization and subsequent dilution in T media/1% FBS, 5 × 10 4 cells in 50-μl volume were added to the top wells. The chamber was then incubated at 37°C for 4 hours. The side of the filter onto which the cells were loaded was then scraped free of cells and the membrane was subsequently fixed in 10% formalin for 45 minutes, washed in phosphate-buffered saline, and stained overnight in Gill’s hematoxylin. The number of cells traversing the membrane (10-μm pore size) was counted and analyzed using a statistical software package (NIH image version 1.56). NbE-1 and FB2 proliferation was assayed by measuring DNA synthesis as previously described. 43 Briefly, cells were seeded into 48-well plates at densities of 2 × 10 4 and 5 × 10 4 cells/well in medium containing 0.25% FBS. After 24, 48, and 72 hours, 3H-thymidine (5 μCi/ml) was added and cells were cultured for an additional 24 hours. The cells were washed and lysed and 3H-thymidine incorporation into DNA was measured.

Results

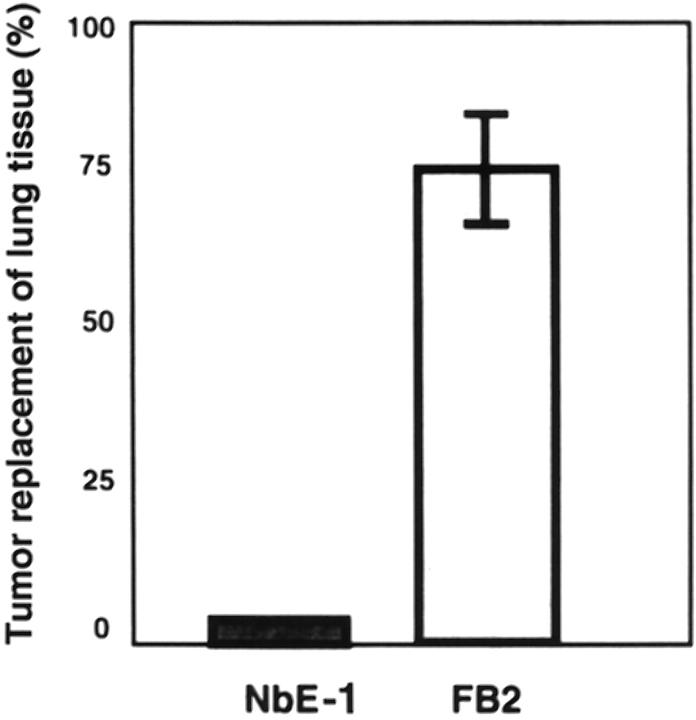

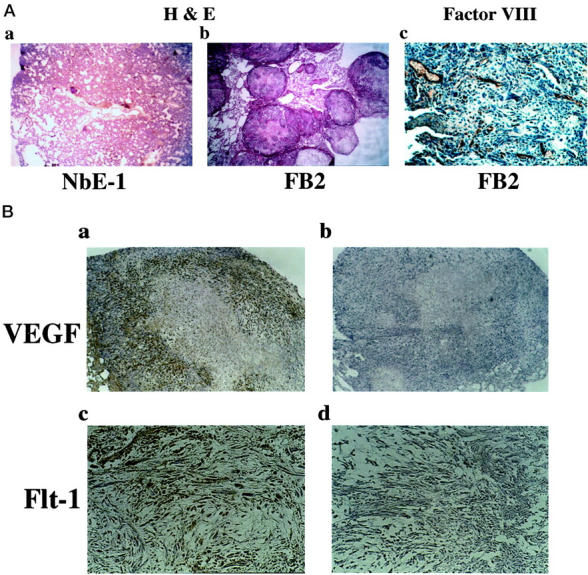

FB2 cells were shown previously to be spontaneously motile and invasive. 42 Gene and protein expression changes, consistent with the hypothesis that FB2 cells are intrinsically more metastatic than the NbE-1 parent cells, were also observed in this earlier study. To test this prediction directly, equal numbers of NbE-1 cells and FB2 cells were injected into the circulation of syngeneic NBL/CRX rats by direct injection into the vena cava. Because the tumor cells are injected into the vena cava, they will circulate to the lungs where they may initiate metastases. FB2 cells formed rapidly growing tumors readily in the lungs, whereas NbE-1 cells were nontumorigenic using this assay system. The lungs of FB2-injected rats demonstrated extensive replacement (75%) of lung parenchyma by tumor cells (Figures 1 and 2Ab ▶ ▶ ). In contrast, the lungs of NbE-1-injected rats had a normal histological appearance and were normal in size (Figures 1 and 2Aa ▶ ▶ ). FB2 tumors retrieved from the lungs of the host animals contained extensive necrotic central zones and healthy appearing tumor areas surrounding them. Several blood capillaries were detected outside the necrotic areas by immunohistochemical staining with anti-Factor VIII antibodies (Figure 2Ac ▶ ). These vessels were probably formed as the tumor cells were filling the lung nodule. Immunostaining with anti-VEGF antibodies resulted in no staining in the necrotic zones, strong staining in the intermediate zones closer to the tumor periphery, and low or negligible staining at the tumor periphery (Figure 2Ba ▶ ). This pattern of staining is consistent with up-regulation of VEGF in hypoxic areas of the tumor, and lower VEGF expression in peripheral areas with relatively high oxygen perfusion. These results indicate that FB2-derived tumors express VEGF and are capable of neovascularization.

Figure 1.

Growth properties of NbE-1- and FB2-derived tumors. NbE-1 and FB2 cells (1 × 107) were delivered into the circulation by direct injection into the inferior vena cava of 5-week-old NBL/CRX rats. Rats were sacrificed 4 weeks after injection and lungs were examined histologically. The area substituted by tumor cells was calculated as described in Material and Methods.

Figure 2.

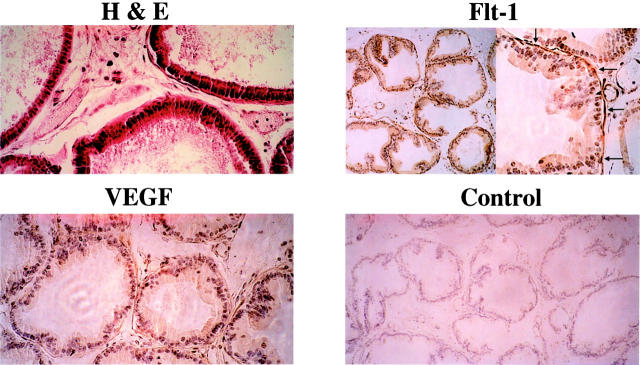

Angiogenic properties of FB2-derived tumors. Tumors were generated from FB2 cells as described in Figure 1 ▶ . The lungs were excised when the animals were sacrificed, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned. A: Histological staining using H&E shows normal lung appearance in NbE-1-injected rats [original magnification, ×25 (a)], whereas many of the lung nodules of FB2-injected rats were occupied by tumor cells [original magnification, ×40 (b)]. One lung nodule occupied by FB2 tumor was sectioned and stained with anti-factor VIII [original magnification, ×250 (c)]. B: FB2 tumor sections were immunostained with anti-VEGF [original magnifications, ×100 (a and b)] and anti-Flt-1 antibodies [original magnifications, ×100 (c and d)]. To confirm the staining specificity, anti-VEGF and anti Flt-1 antibodies were incubated with the immunizing peptides before the immunostaining (b and d, respectively).

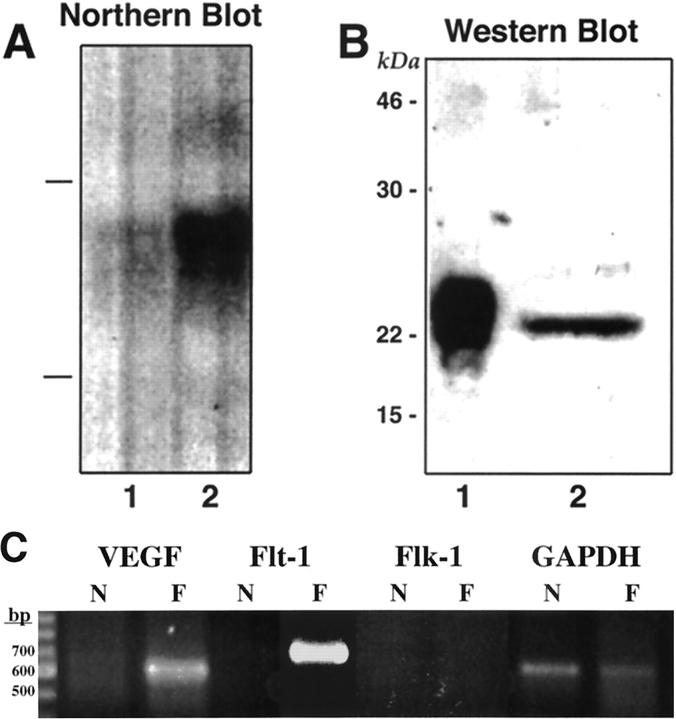

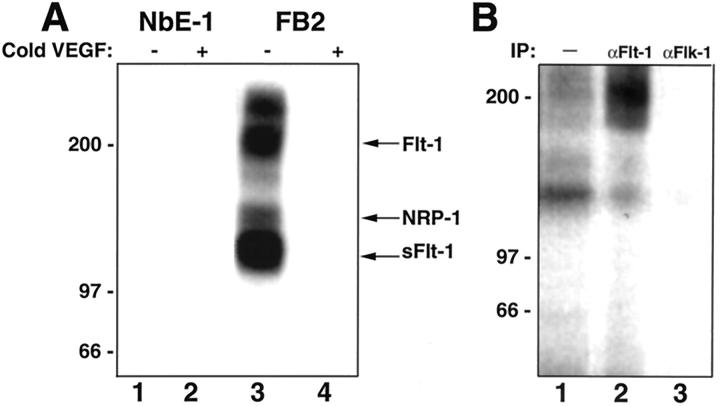

FB2 cells cultured in vitro expressed high levels of VEGF mRNA in comparison to NbE-1 cells, as determined by Northern blot analysis (Figure 3A) ▶ . This result was further supported by RT-PCR analysis of VEGF mRNA levels (Figure 3C) ▶ . VEGF165 was present in FB2-conditioned medium as a 23-kd protein by Western blot analysis, demonstrating its secretion from the cells (Figure 3B) ▶ . It is likely that VEGF secretion by FB2 cells acts physiologically in a paracrine manner (ie, by initiating EC migration and proliferation to enhance angiogenesis). 12 However, to test for the possibility of autocrine signaling, FB2 cells were examined for expression of the VEGF receptors, KDR/flk-1 and Flt-1, initially by RT-PCR. Flt-1 mRNA, but not KDR/flk-1 mRNA, was detected in FB2 cells by this method (Figure 3C) ▶ . To verify this finding and to independently assess whether FB2 cells express functional Flt-1 receptors, chemical cross-linking of 125I-VEGF165 to NbE-1 and FB2 cells was performed. Cross-linking analysis demonstrated the presence of high-affinity VEGF receptors on the surface of FB2 but not NbE-1 cells (Figure 4A) ▶ . The formation of the labeled 125I-VEGF165/receptor complexes was specific because an excess of unlabeled VEGF prevented their formation (Figure 4A, lane 4 versus lane 3). At least four VEGF-containing labeled complexes were detected in FB2 cells. An ∼200-kd complex was immunoprecipitated with anti-Flt-1, but not anti-Flk-1 antibodies, confirming the presence of Flt-1, and the absence of detectable KDR/Flk-1, in the cells (Figure 4B) ▶ . A 130-kd-labeled complex containing soluble Flt-1 protein 17 was formed but was not immunoprecipitated with anti-Flt-1 antibodies because the anti-Flt-1 antibodies used here were raised against the cytoplasmic portion of Flt-1 and they will not recognize soluble Flt-1 proteins. 125I-VEGF165 also specifically bound to an additional receptor on FB2 cells, forming a 170-kd labeled complex (Figure 4A) ▶ . The predicted mass of this receptor is ∼130 kd, strongly suggesting that it corresponds to NRP-1, a high-affinity VEGF receptor that we have recently identified. 33 FB2 cells maintained expression of Flt-1 in FB2-derived tumors in vivo, as demonstrated by immunostaining (Figure 2B, c and d) ▶ . These results indicate that FB2 cells express at least two VEGF receptors, Flt-1 and NRP-1. In contrast, the nontumorigenic NbE-1 parent cell does not express VEGF receptors.

Figure 3.

FB2 cells express high levels of VEGF in vitro. A: Northern blot analysis of VEGF expression. Total RNA (20 μg) from NbE-1 (lane 1) and FB2 (lane 2) cells was separated on a 1% agarose gel. The RNA was transferred to a membrane and probed with human VEGF cDNA. The lines on the left represent the position of the rRNA. B: Detection of VEGF protein in the conditioned medium of FB2 cells. FB2-conditioned medium (200 ml) was passed through a heparin-Sepharose column. The column was washed extensively and bound proteins were eluted by 0.8 mol/L NaCl. Samples of the peak fraction (lane 2) and 50 ng of human recombinant VEGF165 (lane 1) were electrophoresed through 12% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, blotted onto a membrane, and probed with anti-VEGF antibodies. Molecular weight standards are shown on the left. C: RT-PCR analysis of VEGF and VEGF receptors in NbE-1 and FB2 cells. Total RNA (2 μg) extracted from NbE-1 (N) and FB2 (F) cells was used to prepare cDNA using RT. Primers specific for human VEGF, rat Flt-1, rat Flk-1, and rat glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase cDNA sequences were used for the PCR, as indicated. Amplified DNA was separated on a 1.5% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide.

Figure 4.

FB2 cells possess VEGF receptor Flt-1. A: 125I-VEGF165 (5 ng/ml) was bound and cross-linked to subconfluent cultures of NbE-1 (lanes 1 and 2) and FB2 (lanes 3 and 4) cells in 6-cm dishes as described in Materials and Methods. In lanes 2 and 4, the binding was performed in the presence of 1 μg/ml of VEGF165. The cells were lysed and proteins were resolved by 6% SDS-PAGE. The polyacrylamide gel was dried and exposed to X-ray film. Molecular weight standards are shown on the left. B:125I-VEGF165 (5 ng/ml) was bound and cross-linked to FB2 cells as described above. The cells were lysed and 125I-VEGF 165/receptor complexes were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flt-1 (lane 2) and anti-Flk-1 (lane 3) antibodies, as described in Materials and Methods. A sample of the cell lysate, before immunoprecipitation, is shown in lane 1. Immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by 6% SDS-PAGE and the gel was dried and exposed to X-ray film. Molecular weight standards are shown on the left.

The NbE-1 cell line was developed from normal adult rat ventral prostate epithelium and was immortalized by continuous passage in cell culture. 44 Although NbE-1 is a continuous cell line, it expresses a barrier-forming phenotype and a complement of cell surface adhesion molecules suggesting a greater resemblance to normal prostate epithelial cells than to prostate carcinoma cells. 42,45 To identify cell types in the mature rat prostate that might normally express Flt-1, we performed immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 5) ▶ . Glandular epithelial cells were not stained by anti-Flt-1 antibodies, suggesting that the absence of Flt-1 in NbE-1 cells reflects the normal cell-specific pattern of Flt-1 expression. However, periductal smooth muscle cells were positively stained by anti-Flt-1 antibodies.

Figure 5.

Expression of Flt-1 and VEGF in normal rat prostate. Prostates were retrieved from 6-month-old Sprague-Dawley rats, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned. H&E staining shows the glandular structure of the rat prostate (original magnification, ×250). Sections were stained with Flt-1 [original magnifications: ×100 (left), ×250 (right)] and anti-VEGF (original magnification, ×250) antibodies, as indicated. In the control staining, the primary antibody was replaced by normal rabbit IgG. Arrows in the Flt-1-stained section point to the layer of SMCs, which are positively stained for Flt-1.

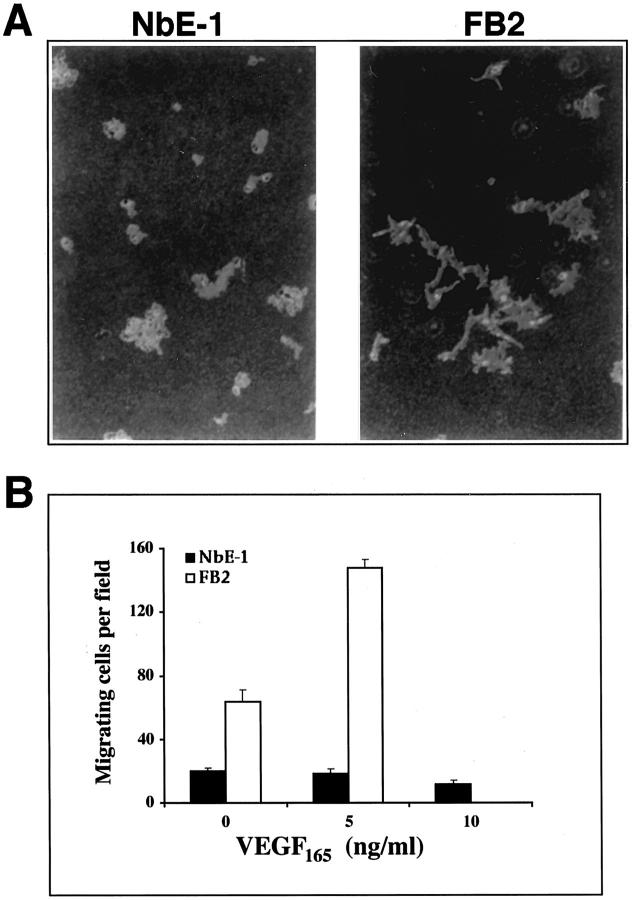

The FB2 subline was originally characterized as a highly motile derivative of NbE-1 cells. In the present study we used the phagokinetic track assay to reassess the intrinsic motile properties of NbE-1 and FB2 cells (Figure 6A) ▶ . In this assay, which measures chemokinetic (random-walk) motility, FB2 cells exhibited a pattern of active cell movement, in marked contrast to a resting cell pattern seen with NbE-1 cells. This result confirms that FB2 cells constitutively are more motile than NbE-1 cells as previously shown. To examine whether VEGF is capable of attracting migratory FB2 cells, a modified Boyden chamber assay was used (Figure 6B) ▶ . FB2 cells exhibited an increased basal movement compared with NbE-1 cells in this assay (63.7 and 19.7 migrating cells per field, respectively). VEGF165 (5 ng/ml) induced more than a twofold increase in FB2 migration (148 migrating cells per field), whereas NbE-1 cell migration was not significantly changed even at higher levels of VEGF165. VEGF165 did not stimulate either DNA synthesis or an increase in cell number with FB2 and NbE-1 cells, suggesting that VEGF is not a mitogen for these cells (not shown). These results suggest that VEGF may promote directed movement of FB2 cells through Flt-1.

Figure 6.

VEGF is a motility factor for FB2 cells. A: Chemokinetic motility: NbE-1 and FB2 cells were seeded onto polystyrene microsphere-coated tissue-culture dishes in medium containing 10% FBS, as indicated. Cell paths were visualized by the formation of phagokinetic tracks throughout a 48-hour period. B: VEGF-induced cell migration in a modified Boyden chamber assay: NbE-1 (filled bars) and FB2 (open bars) cells were seeded in the upper wells of a Boyden chamber in the presence or absence of VEGF165, in the lower wells as indicated. After a 4-hour incubation, the number of cells that had migrated through the filter in each field was counted. Each data point represents the mean ± SD of four independent wells.

Discussion

The growth of solid tumors, encompassing tumor cell proliferation and stromal expansion, is dependent on the ability of the tumor to evoke a local angiogenic reaction. 1,46 Subsequently, metastasis from the primary tumor is dependent in part on the invasive and motile properties of the disseminating tumor cells. 47 A common feature in each of these phases of tumor progression is the production of angiogenic factors by the tumor cells. In recent years, there has been growing evidence that VEGF plays a major role in promoting tumor angiogenesis via paracrine effects on capillary growth. 12

Recent studies have implicated the angiogenic phenotype in progression and metastasis in prostate and bladder carcinomas. 48 Several studies have shown a correlation between tumor neovascularization, as measured by microvessel density, and advanced stage of prostate cancer. 34,38,49 Microvessel density was significantly higher in tumors of patients with metastatic disease than those without metastases. These observations were accompanied by analyses of angiogenic growth factors in prostate tumors. Increased expression of basic fibroblast growth factor, transforming growth factor, epidermal growth factor, and platelet-derived growth factor was found in malignant prostatic epithelial cells compared to normal controls. 48

We have previously reported on the generation of a rat prostate epithelial cell lineage, comprising stable cell lines representing the transition from low to high motility, as seen with metastatic prostate tumors. 42 The NbE-1 parent cell line expresses a barrier-forming epithelial morphology and low intrinsic motility. FB2 is an invasive, spontaneously arising variant of NbE-1, that exhibits no barrier-forming properties and high chemokinetic motility. In this study we have analyzed the potential consequences of altered VEGF expression and VEGF receptor expression in this cell system.

We confirmed in this study that FB2 cells possess metastatic capabilities by using an assay system that requires survival of cells in the circulation, invasion, and cell growth in the lung parenchyma. In this assay, FB2 cells formed extensive, rapidly growing metastatic nodules in the lungs. In contrast, no NbE-1-derived tumors were found in the lungs. In vitro, FB2 cells secreted large amounts of VEGF into the medium compared to marginal VEGF levels expressed by NbE-1 cells, which were detected only by RT-PCR. These results indicate that VEGF expression is correlated with the dramatic differences in tumor-forming capability exhibited by FB2 and NbE-1 cells. FB2 cells maintained high VEGF expression in the tumors, and were capable of evoking an angiogenic reaction, as judged by blood vessel staining. These findings are consistent with previous reports of elevated levels of VEGF production in metastatic human prostate carcinoma cells in comparison to slightly metastatic or nonmetastatic lines. 38 Similar findings of elevated VEGF expression in metastatic tumors were observed in the Dunning rat prostate cancer model. 50 We have recently shown that levels of VEGF in the plasma of patients with metastatic prostate cancer are significantly higher than in patients with localized disease. 39 Accordingly, anti-VEGF antibodies were shown to suppress tumor growth of prostate carcinoma lines in mice and to inhibit tumor metastasis. 51

VEGF binds to two distinct high-affinity receptors, KDR/Flk-1 and Flt-1, generally expressed exclusively by ECs. 52-54 These receptors, possibly in concert with the recently described co-receptor, NRP-1, mediate the biological activity of VEGF. 33 The expression of VEGF receptors is up-regulated in blood capillaries at sites of active angiogenesis found in tumors, wounds, and in the eyes of diabetics. 15,55 When we examined NbE-1 and FB2 cells for binding of 125I-VEGF165 we were able to detect specific VEGF/receptor-labeled complexes in FB2 cells but not in NbE-1 cells. Immunoprecipitation experiments further indicated that FB2 cells express Flt-1 and not Flk-1. These results suggest that Flt-1 is among several other genes whose expression has changed in the transition from the benign phenotype expressed by NbE-1 cells to the malignant phenotype expressed by FB2 cells. Expression of Flt-1 was also detected in FB2-derived tumors, suggesting that Flt-1 expression by FB2 is not confined to in vitro conditions but that the cells maintain the expression of this receptor in vivo. Our findings are consistent with those recently reported by Ferrer and colleagues 40 and Hahn and colleagues, 41 who detected Flt-1-positive tumor cells in the majority of human prostate tumor specimens examined. Much of the tumor cell-associated Flt-1 immunoreactivity was localized to benign and normal areas and less in foci of carcinoma within the tumor. 40 We and others have previously observed Flt-1 and KDR/Flk-1 expression in melanoma-derived cell lines, 31 whereas normal melanocytes were devoid of VEGF receptors. 30,32,44 Although a functional role for VEGF receptor expression in these cells has not been reported, these observations suggest that expression of VEGF receptors is associated with the malignant phenotype in two different epithelial tissues, the prostate and the skin.

What is the possible role of Flt-1 in FB2 tumorigenicity? Because the FB2 cell line was originally identified as a highly motile variant of the NbE-1 cell line, we determined whether VEGF was capable of inducing FB2 cell migration. When VEGF was presented to the cells in a directed manner, the number of FB2 cells migrating toward the VEGF source was more than twofold higher than could be accounted for by random migration. In contrast, NbE-1 cells did not increase their movement in the presence of VEGF. These results suggest that VEGF is a chemoattractant for FB2 but not for NbE-1 cells. Because we excluded the possibility that KDR/Flk-1 is a functional VEGF receptor in this cell line, the motile signal is highly likely to be transmitted through Flt-1. This is the first example of a functional role for Flt-1 in tumor-derived cells. Although VEGF has previously been reported to be a chemoattractant for ECs, VEGF had no effect on cell migration in ECs that expressed only Flt-1. 25 VEGF and the related growth factor, PlGF, have been shown to induce chemotaxis of monocytes. 29,56 It was subsequently shown that monocytes express Flt-1 but not KDR/Flk-1, suggesting that VEGF signaling through Flt-1 may use different pathways in ECs and in non-ECs. Taken together, our results point to VEGF as an autocrine stimulator of FB2 migration.

We have recently characterized and cloned a novel VEGF receptor, NRP-1, which is expressed by ECs as well as by a wide variety of tumor-derived cells including PC3 and LNCaP human prostate carcinoma cells. 33,44 In this study, examination of the 125I-VEGF165 cross-linking results revealed the formation of an additional VEGF/receptor labeled complex of ∼170 kd that was not immunoprecipitated by anti-Flt-1 antibodies. The size of this complex is similar to the complex formed by binding of VEGF to NRP-1, 31 suggesting that FB2 cells express two VEGF receptors, Flt-1 and NRP-1. NRP-1 expression was recently examined in prostate tumor specimens of different clinical stages. Using quantitative RT-PCR it was shown that NRP-1 was overexpressed in tumors with advanced disease. 57 Interestingly, in this study VEGF overexpression was correlated with the early stage of prostate tumor progression. Taken together, it seems that expression of VEGF receptors such as Flt-1 and NRP-1 by prostate tumor cells might be correlated with the relative aggressiveness of the tumor. In ECs, NRP-1 serves as a co-receptor for KDR. It enhances VEGF165 binding to KDR and KDR-mediated EC migration. PlGF, another ligand of Flt-1, was recently shown to bind NRP-1. 58 Thus, it is possible that VEGF165 and PlGF use NRP-1 as a co-receptor for Flt-1. We are currently investigating the role of NRP-1 in the interaction between VEGF and Flt-1 in ECs and tumor-derived cells.

Lastly, an interesting result that warrants further study is the finding that Flt-1 is normally expressed by periductal smooth muscle cells of the normal rat prostate. Flt-1 has been previously localized to vascular and uterine smooth muscle cells. 59,60 The smooth muscle cell layer in the rat prostate is arrayed circumferentially around the glandular elements of the ductal tree and these cells are believed to mediate aspects of stromal-epithelial signaling. 61 An interesting possibility is that the expression of Flt-1 by FB2 and other prostate tumor cells might be a reflection of smooth muscle cell gene expression. These changes in gene expression would presumably confer novel characteristics to the tumor cells that may be relevant to the metastatic process. Further analyses of Flt-1 expression by FB2 cells and in human prostate tumors is required to determine whether Flt-1 has an important role in cancer progression and whether this marker is an informative clinical indicator.

In summary, we have shown that an autocrine signaling loop, involving the angiogenic factor VEGF and the VEGF receptor, Flt-1, emerged spontaneously in a cell line family with progression to a more malignant phenotype. Further experiments are required to determine whether VEGF-dependent autocrine signaling is a common feature of disease progression in human prostate cancer or possibly in other solid tumor systems.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Shay Soker, Ph.D., Dept. of Urology, Children’s Hospital, 300 Longwood Ave., Boston, MA 02115.

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO1 DK47556, RO1 CA77386, and RO1 DK49484).

References

- 1.Klagsbrun M, Moses MA: Molecular angiogenesis. Chem Biol 1999, 6:R217-R224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folkman J, Brem H: Angiogenesis and inflammation. ed 2 Gallin JI Goldstein IM Snyderman R eds. Inflammation: Basic Principles and Clinical Correlates, 1992, :pp 821-839 Raven Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 3.Risau W: Mechanisms of angiogenesis. Nature 1997, 386:671-674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Risau W, Flamme I: Vasculogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 1995, 11:73-91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanahan D, Folkman J: Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell 1996, 86:353-364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rivard A, Isner JM: Angiogenesis and vasculogenesis in treatment of cardiovascular disease. Mol Med 1998, 4:429-440 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shweiki D, Itin A, Neufeld G, Gitay-Goren H, Keshet E: Patterns of expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGF receptors in mice suggest a role in hormonally regulated angiogenesis. J Clin Invest 1993, 91:2235-2243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank S, Hubner G, Breier G, Longaker MT, Greenhalgh DG, Werner S: Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in cultured keratinocytes: implications for normal and impaired wound healing. J Biol Chem 1995, 270:12607-12613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Battegay EJ: Angiogenesis: mechanistic insights, neovascular diseases, and therapeutic prospects. J Mol Med 1995, 73:333-346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Folkman J: Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Hospital, Boston. Clinical applications of research on angiogenesis. N Engl J Med 1995, 333:1757-1763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keck PJ, Hauser SD, Krivi G, Sanzo K, Warren T, Feder J, Connolly DT: Vascular permeability factor, an endothelial cell mitogen related to PDGF. Science 1989, 246:1309-1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrara N, Davis-Smith T: The biology of vascular endothelial growth factor. Endocr Rev 1997, 18:4-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shweiki D, Itin A, Soffer D, Keshet E: Vascular endothelial growth factor induced by hypoxia may mediate hypoxia-initiated angiogenesis. Nature 1992, 359:843-845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dvorak HF, Sioussat TM, Brown LF, Berse B, Nagy JA, Sotrel A, Manseau EJ, Van de Water L, Senger DR: Distribution of vascular permeability factor (vascular endothelial growth factor) in tumors: concentration in tumor blood vessels. J Exp Med 1991, 174:1275-1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plate KH, Breier G, Millauer B, Ullrich A, Risau W: Up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor and its cognate receptors in a rat glioma model of tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Res 1993, 53:5822-5827 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim KJ, Li B, Winer J, Armanini M, Gillett N, Phillips HS, Ferrara N: Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis suppresses tumour growth in vivo. Nature 1993, 362:841-844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kendall RL, Thomas KA: Inhibition of vascular endothelial cell growth factor activity by an endogenously encoded soluble receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993, 90:10705-10709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aiello LP, Pierce EA, Foley ED, Takagi H, Chen H, Riddle L, Ferrara N, King GL, Smith LE: Suppression of retinal neovascularization in vivo by inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) using soluble VEGF-receptor chimeric proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995, 92:10457-10461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strawn LM, McMahon G, App H, Schreck R, Kuchler WR, Longhi MP, Hui TH, Tang C, Levitzki A, Gazit A, Chen I, Keri G, Orfi L, Risau W, Flamme I, Ullrich A, Hirth KP, Shawver LK: Flk-1 as a target for tumor growth inhibition. Cancer Res 1996, 56:3540-3545 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrara N, Carver-Moore K, Chen H, Dowd M, Lu L, O’Shea KS, Powell-Braxton L, Hillan KJ, Moore MW: Heterozygous embryonic lethality induced by targeted inactivation of the VEGF gene. Nature 1996, 380:439-442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carmeliet P, Ferreira V, Breier G, Pollefeyt S, Kieckens L, Gertsenstein M, Fahrig M, Vandenhoeck A, Harpal K, Eberhardt C, Declercq C, Pawling J, Moons L, Collen D, Risau W, Nagy A: Abnormal blood vessel development and lethality in embryos lacking a single VEGF allele. Nature 1996, 380:435-439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shibuya M, Yamaguchi S, Yamane A, Ikeda T, Tojo A, Matsushime H, Sato M: Nucleotide sequence and expression of a novel human receptor-type tyrosine kinase gene (flt) closely related to the fms family. Oncogene 1990, 5:519-524 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terman BI, Dougher-Vermazen M, Carrion ME, Dimitrov D, Armellino DC, Gospodarowicz D, Bohlen P: Identification of the KDR tyrosine kinase as a receptor for vascular endothelial cell growth factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1992, 187:1579-1586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Vries C, Escobedo JA, Ueno H, Houck K, Ferrara N, Williams LT: The fms-like tyrosine kinase, a receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor. Science 1992, 255:989-991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waltenberger J, Claesson-Welsh L, Siegbahn A, Shibuya M, Heldin CH: Different signal transduction properties of KDR and Flt1, two receptors for vascular endothelial growth factor. J Biol Chem 1994, 269:26988-26995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seetharam L, Gotoh N, Maru Y, Neufeld G, Yamaguchi S, Shibuya M: A unique signal transduction from FLT tyrosine kinase, a receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor VEGF. Oncogene 1995, 10:135-147 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fong GH, Zhang L, Bryce DM, Peng J: Increased hemangioblast commitment, not vascular disorganization, is the primary defect in flt-1 knock-out mice. Development 1999, 126:3015-3025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Enomoto T, Okamoto T, Sato JD: Vascular endothelial growth factor induces the disorganization of actin stress fibers accompanied by protein tyrosine phosphorylation and morphological change in Balb/C3T3 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1994, 202:1716-1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clauss M, Weich H, Breier G, Knies U, Rockl W, Waltenberger J, Risau W: The vascular endothelial growth factor receptor Flt-1 mediates biological activities. Implications for a functional role of placenta growth factor in monocyte activation and chemotaxis. J Biol Chem 1996, 271:17629-17634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terman B, Khandke L, Dougher-Vermazan M, Maglione D, Lassam NJ, Gospodarowicz D, Persico MG, Bohlen P, Eisinger M: VEGF receptor subtypes KDR and FLT1 show different sensitivities to heparin and placenta growth factor. Growth Factors 1994, 11:187-195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soker S, Fidder H, Neufeld G, Klagsbrun M: Characterization of novel vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors on tumor cells that bind VEGF165 via its exon 7-encoded domain. J Biol Chem 1996, 271:5761-5767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gitay-Goren H, Halaban R, Neufeld G: Human melanoma cells but not normal melanocytes express vascular endothelial growth factor receptors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1993, 190:702-709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soker S, Takashima S, Miao HQ, Neufeld G, Klagsbrun M: Neuropilin-1 is expressed by endothelial and tumor cells as an isoform-specific receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor. Cell 1998, 92:735-745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weidner N, Carroll PR, Flax J, Blumenfeld W, Folkman J: Tumor angiogenesis correlates with metastasis in invasive prostate carcinoma. Am J Pathol 1993, 143:401-409 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bettencourt MC, Bauer JJ, Sesterhenn IA, Connelly RR, Moul JW: CD34 immunohistochemical assessment of angiogenesis as a prognostic marker for prostate cancer recurrence after radical prostatectomy. J Urol 1998, 160:459-465 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borre M, Offersen BV, Nerstrom B, Overgaard J: Microvessel density predicts survival in prostate cancer patients subjected to watchful waiting. Br J Cancer 1998, 78:940-944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mydlo JH, Kral JG, Volpe M, Axotis C, Macchia RJ, Pertschuk LP: An analysis of microvessel density, androgen receptor, p53 and HER-2/neu expression and Gleason score in prostate cancer. Preliminary results and therapeutic implications. Eur Urol 1998, 34:426-432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balbay MD, Pettaway CA, Kuniyasu H, Inoue K, Ramirez E, Li E, Fidler IJ, Dinney CP: Highly metastatic human prostate cancer growing within the prostate of athymic mice overexpresses vascular endothelial growth factor. Clin Cancer Res 1999, 5:783-789 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duque JL, Loughlin KR, Adam RM, Kantoff PW, Zurakowski D, Freeman MR: Plasma levels of vascular endothelial growth factor are increased in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Urology 1999, 54:523-527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hahn D, Simak R, Steiner GE, Handisurya A, Susani M, Marberger M: Expression of the VEGF-receptor Flt-1 in benign, premalignant and malignant prostate tissues. J Urol 2000, 164:506-510 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferrer FA, Miller LJ, Lindquist R, Kowalczyk P, Laudone VP, Albertsen PC, Kreutzer DL: Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors in human prostate cancer. Urology 1999, 54:567-572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Freeman MR, Bagli DJ, Lamb CC, Guthrie PD, Uchida T, Slavin RE, Chung LW: Culture of a prostatic cell line in basement membrane gels results in an enhancement of malignant properties and constitutive alterations in gene expression. J Cell Physiol 1994, 158:325-336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soker S, Gollamudi-Payne S, Fidder H, Charmahelli H, Klagsbrun M: Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-induced endothelial cell proliferation by a peptide corresponding to the exon 7-encoded domain of VEGF165. J Biol Chem 1997, 272:31582-31588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chung LW, Chang SM, Bell C, Zhau HE, Ro JY, von Eschenbach AC: Co-inoculation of tumorigenic rat prostate mesenchymal cells with non-tumorigenic epithelial cells results in the development of carcinosarcoma in syngeneic and athymic animals. Int J Cancer 1989, 43:1179-1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kleinerman DI, Troncoso P, Lin SH, Pisters LL, Sherwood ER, Brooks T, von Eschenbach AC, Hsieh JT: Consistent expression of an epithelial cell adhesion molecule (C-CAM) during human prostate development and loss of expression in prostate cancer: implication as a tumor suppressor. Cancer Res 1995, 55:1215-1220 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Folkman J: Angiogenesis and angiogenesis inhibition: an overview. EXS 1997, 79:1-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zetter BR: Angiogenesis and tumor metastasis. Annu Rev Med 1998, 46:407-424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Campbell SC: Advances in angiogenesis research: relevance to urological oncology. J Urol 1997, 158:1663-1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brawer MK, Deering RE, Brown M, Preston SD, Bigler SA: Predictors of pathologic stage in prostatic carcinoma. The role of neovascularity. Cancer 1994, 73:678-687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haggstrom S, Bergh A, Damber JE: Vascular endothelial growth factor content in metastasizing and nonmetastasizing Dunning prostatic adenocarcinoma. Prostate 2000, 15:42-50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Melnyk O, Zimmerman M, Kim KJ, Shuman M: Neutralizing anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody inhibits further growth of established prostate cancer and metastases in a pre-clinical model. J Urol 1999, 161:960-963 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neufeld G, Cohen T, Gengrinovitch S, Poltorak Z: Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors. FASEB J 1999, 13:9-22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petrova TV, Makinen T, Alitalo K: Signaling via vascular endothelial growth factor receptors. Exp Cell Res 1999, 253:117-130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Veikkola T, Alitalo K: VEGFs, receptors and angiogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol 1999, 9:211-220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Plate KH, Breier G, Weich HA, Mennel HD, Risau W: Vascular endothelial growth factor and glioma angiogenesis: coordinate induction of VEGF receptors, distribution of VEGF protein and possible in vivo regulatory mechanisms. Int J Cancer 1994, 59:520-529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barleon B, Sozzani S, Zhou D, Weich HA, Mantovani A, Marme D: Migration of human monocytes in response to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is mediated via the VEGF receptor flt-1. Blood 1996, 87:3336-3343 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Latil A, Bieche I, Pesche S, Valeri A, Fournier G, Cusseno TO, Lidereau R: VEGF overexpression in clinically localized prostate tumors and neuropilin-1 overexpression in metastatic forms. Int J Cancer 2000, 89:167-171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Migdal M, Huppertz B, Tessler S, Comforti A, Shibuya M, Reich R, Baumann H, Neufeld G: Neuropilin-1 is a placenta growth factor-2 receptor. J Biol Chem 1998, 273:22272-22278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Couper LL, Bryant SR, Eldrup-Jorgensen J, Bredenberg CE, Lindner V: Vascular endothelial growth factor increases the mitogenic response to fibroblast growth factor-2 in vascular smooth muscle cells in vivo via expression of fms-like tyrosine kinase-1. Circ Res 1997, 81:932-939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brown LF, Detmar M, Tognazzi K, Abu-Jawdeh G, Iruela-Arispe ML: Uterine smooth muscle cells express functional receptors (flt-1 and KDR) for vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor. Lab Invest 1997, 76:245-255 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cunha GR, Hayward SW, Dahiya R, Foster BA: Smooth muscle-epithelial interactions in normal and neoplastic prostatic development. Acta Anat 1996, 155:63-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]