Abstract

Collagen X transgenic (Tg) mice displayed skeleto-hematopoietic defects in tissues derived by endochondral skeletogenesis. 1 Here we demonstrate that co-expression of the transgene product containing truncated chicken collagen X with full-length mouse collagen X in a cell-free translation system yielded chicken-mouse hybrid trimers and truncated chicken homotrimers; this indicated that the mutant could assemble with endogenous collagen X and thus had potential for dominant interference. Moreover, species-specific collagen X antibodies co-localized the transgene product with endogenous collagen X to hypertrophic cartilage in growth plates and ossification centers; proliferative chondrocytes also stained diffusely. Electron microscopy revealed a disrupted hexagonal lattice network in the hypertrophic chondrocyte pericellular matrix in Tg growth plates, as well as altered mineral deposition. Ruthenium hexamine trichloride-positive aggregates, likely glycosaminoglycans (GAGs)/proteoglycans (PGs), were also dispersed throughout the chondro-osseous junction. These defects likely resulted from transgene co-localization and dominant interference with endogenous collagen X. Moreover, altered GAG/PG distribution in growth plates of both collagen X Tg and null mice was confirmed by a paucity of staining for hyaluronan and heparan sulfate PG. A provocative hypothesis links the disruption of the collagen X pericellular network and GAG/PG decompartmentalization to the potential locus for hematopoietic failure in the collagen X mice.

The majority of the vertebrate skeleton, including the axial and appendicular structures as well as certain cranial bones, forms primarily by endochondral ossification (EO). Through this multistep sequence, the cartilaginous template of these structures is replaced by trabecular bone and marrow. The distinctive feature of this mechanism comprises the hypertrophic cartilage matrix where EO initiates, and where collagen X is the major biosynthetic product.

Collagen X has been associated with EO by its predominant expression in a subset of cartilage cells, the hypertrophic chondrocytes. 2 On hypertrophy, the cartilage matrix changes from being avascular and noncalcifiable to one that is penetrable by blood vessels and capable of calcification. This results in an influx of chondroclasts/osteoclasts that degrade hypertrophic cartilage, and of stem cells that give rise to bone and marrow stroma. Thus, trabecular bone forms on top of hypertrophic cartilage remnants, whereas the stroma establishes niches for hematopoiesis. The continual replacement of hypertrophic cartilage by bone and marrow gives rise to growth plates at outer tissue ends that provide potential for longitudinal growth by EO. 2

The localization of collagen X to hypertrophic chondrocytes distinguishes these cells as those destined for replacement by bone and marrow, and predicts that collagen X may participate in EO-associated events, namely mineralization, vascular invasion, matrix stabilization, or establishment of a marrow environment. 2 Consequently, disruption of collagen X function may manifest as an impairment of EO. To test this possibility, we generated Tg mice carrying dominant interference mutations in collagen X. 3 Transgene constructs encoded chicken collagen X variants with in-frame deletions in the central triple-helical domain, but with intact NC1 and NC2 domains. Transgene expression was targeted to hypertrophic cartilage by either a 4.9-kb or a 1.6-kb chicken collagen X promotor fragment. Our construct design assumed that truncated chicken collagen X transgene products would compete with endogenous mouse collagen X chains for association at NC1 domains; however, because of the triple-helical deletions, hybrid trimers would not fold into stable trimeric collagens. Consequently, all three chains would either be degraded, or would persist as abnormal molecules that could disrupt endogenous collagen X supramolecular assembly. Likewise, truncated chicken homotrimers might persist and compete with collagen X for interactions. For example, the NC2 and NC1 domains of collagen X are retained extracellularly and may aggregate into hexagonal arrays around hypertrophic chondrocytes. 4,5 The structural contribution of collagen X to a lattice-like network may be key to its function; these associations may be disrupted by the dominant interference collagen X mutations.

Transgene expression in hypertrophic cartilage yielded skeleto-hematopoietic defects in multiple Tg mouse lines, representing all constructs and containing independent transgene insertions. 3 Phenotype severity in each line ranged from perinatal lethality to variable dwarfism, and involved all EO-derived tissues. Skeletal deformities included growth plate compressions, diminished hypertrophy, and reduced trabecular bone; hematopoietic defects manifested as marrow hypoplasia and impaired hematopoiesis (O. Jacenko, D. Roberts, M. Campbell, P. McManus, C. Gress, and Z. Tao, submitted manuscript). A subset (∼25%) of mice with perinatal lethality manifested the most severe skeletal defects, marrow aplasia, lymphopenia, and lymphatic organ atrophy. Survivors (∼75%) exhibited subtle hematopoietic changes including elevated splenic T cells, a reduction of marrow and splenic B cells, and a predisposition to lymphosarcomas. Growth plate 6 and hematopoietic 1 abnormalities were also observed in the collagen X KO mice; 2 some of these features, in particular the perinatal lethality and marrow aplasia in a subset of the KO mice, mirrored the Tg mouse defects. 1 These hematopoietic defects underscored an unforeseen link between hypertrophic cartilage, EO, and establishment of a marrow microenvironment required for blood cell differentiation.

Over 30 mutations in collagen X were identified in patients with Schmid metaphyseal chondrodysplasia (SMCD) 2 and with the Japanese-type spondylometaphyseal dysplasia (SMD). 7 Interestingly, most mutations localized to microdomains within the carboxyl NC1 domain; no triple-helical collagen X mutations have yet been found. For SMCD, haploinsufficiency was proposed as a disease mechanism, although for certain mutations, dominant interference was a possibility. 2,8 The onset of SMCD correlates with weight bearing and affects skeletal elements under the greatest mechanical stress; patients exhibit dwarfism, coxa vara, and a waddling gait. 9 A recent clinical re-evaluation of SMCD has identified vertebral changes as a variable component of SCMD, indicating that SMCD and the Japanese-type SMD are identical collagen X disorders; this grouped SCMD as part of the SMD spectrum. 10 Although the SMCD/SMD patients shared specific skeletal defects and dwarfism seen in either the Tg or KO mice, hematopoietic or immune function abnormalities were not described in the affected individuals.

To understand the inconsistencies between the murine and human disease phenotypes, the molecular mechanisms underlying these collagen X disorders must be identified. Moreover, to directly link hypertrophic cartilage and collagen X to marrow establishment, the primary defects because of collagen X disruption need to be recognized. Here we provide evidence that the mechanism of transgene action is consistent with dominant interference; this implies that additional human osteochondrodysplasias or hematological disorders may result from mutations in different collagen X domains, such as the triple helix. Furthermore, we identify a defect in the pericellular matrix of hypertrophic cartilage, which may decompartmentalize the chondro-osseous junction. Moreover, our data indicate an altered distribution of hyaluronan (HA) and heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) in growth plates of both Tg and KO mice; it is noteworthy that these particular glycosaminoglycan (GAG)/proteoglycan (PG) members are implicated in the establishment of marrow microenvironments prerequisite for hematopoiesis. 11-13

Materials and Methods

Cell-Free Translation and in Vitro Trimerization

Plasmids containing SpLX or SpLXH, the chicken collagen X cDNAs with triple-helical deletions, 3 and mX, the full-length mouse collagen X cDNA, 14 were purified by CsCl2 centrifugation. 15 Ethidium bromide was extracted with isopropanol equilibrated with NaCl-saturated Tris-ethylene diamine tetraacetate (EDTA), and dialyzed against milli-Q water. Purified plasmids (0.25 μg) were translated in a reaction volume of 12.5 μl using the TNT-coupled transcription and translation system (Promega, Madison, WI). 16-18 SpLX and SpLXH were transcribed with SP6 polymerase, whereas mX was transcribed with T7 polymerase. For heterotrimer assembly, 0.25 μg of each plasmid were co-translated. To achieve a similar expression level in heterotrimer formation between different collagen X chains, the amount of plasmids used for transcription were adjusted (with a comparable adjustment in amount of RNA polymerase). Trimer assembly was analyzed using two approaches: first, 2.5 μl aliquots of a standard reaction mixture at the completion of co-translation were incubated (37°C, 10 minutes) in 20 μl of 50 mmol/L Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, containing 5 mmol/L CaCl2, representing conditions favoring in vitro chain association. Second, canine microsomal membranes (Promega) were included during cell-free translation to promote trimerization under more physiological conditions. 18 Analysis of the resultant [35S-methionine]-labeled products was by 7.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and fluorography. Samples were denatured (60°C, 10 minutes) before electrophoresis.

Mouse Maintenance

Mice homozygous for the collagen X transgenes 3 or for the null allele 19 were housed in two separate rooms in a virus-free colony in microisolators, and fed autoclaved Purina mouse chow and water ad lib. From birth, mice were inspected daily for growth, behavioral, skeletal, or hematopoietic defects. 1 Weaning was at day 21 and at that time point mice were also ear-punched for identification, and a tail biopsy was obtained if genotyping was needed. 3 Euthanization involved methoxyflurane (Mallinckrodt Veterinary, Mundelein, IL).

Generation of Polyclonal Mouse Collagen X Antibodies

The 162 amino-acid residue NC1 domain of mouse collagen X, 14 fused to the carrier protein TrpE, was used as antigen. Briefly, the region of the mouse collagen X gene encoding NC1 was amplified by polymerase chain reaction, and inserted into a vector (PATH 1) specifically developed for the expression of TrpE fusion proteins. 20 This allowed for a high-expression level of the fused protein in Escherichia coli, followed by a large scale preparation of the antigen without contaminating eukaryotic proteins. Antisera from two immunized rabbits were subsequently purified by affinity chromatography using a TrpE column, 21 and their specificities were confirmed by immunohistochemistry.

Histology

Femurs and tibiae were dissected from newborn to week 3 wild-type controls, collagen X KO mice, and Tg mice from lines 4200-21 (1-2 line containing the 4.2-kb promotor and SpLX cDNA with the 21 amino acid triple-helical deletion) and 1600-293 (3-2 line containing the 1.6-kb promotor and SpLXH cDNA with the 293 amino acid triple-helical deletion) with mild or perinatal-lethal phenotypes (8 to 12 mice per group). Other tissues included brain, eyes, calvaria, thymus, heart, lung, liver, spleen, kidney, and skin from week 3 mice. Samples were either fixed (4% formaldehyde/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, 4°C, 1 week) for histology, or embedded (Tissue Tek OCT, Miles, Elkhart, IN) unfixed for immunohistochemistry. Fixed samples were rinsed in deionized water (DT), limbs were decalcified (4% formalin, 1% sodium acetate, 10% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), and dehydrated in ascending ethanols. After clearing with Propar (Anatech, Battle Creek, MI) and paraffin embedding, 6-μm sections were heat-fixed onto slides and stained with Alcian blue, pH 1.0, for sulfated GAGs, and with Harris hematoxylin and eosin Y (H&E; Sigma Diagnostics, St. Louis, MO) for morphology.

Immunohistochemistry for collagen X, CD44, and CD138 involved fixing (acetone:methanol, 1:1, v:v; 1 minute) 6- to 8-μm cryosections of tibiae and femurs, rinsing in PBS (8 minutes, two changes), and treating with testicular hyaluronidase (1 mg/ml, 45 minutes, 37°C). After rinses (PBS, 6 minutes, three changes), sections were incubated with Immunopure Peroxidase Suppressor (45 minutes; Pierce, Rockford, IL), washed in 4% heat inactivated newborn calf serum (NCS) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) in PBS (15 minutes, three changes), and reacted with primary anti-mouse antibodies (in NCS/PBS; 1 hour, 23°C). Primary antibodies included: mouse collagen X polyclonal (1:1500 dilution); chicken collagen X polyclonal (1:250 dilution; generously provided by Dr. M. Pacifici, University of Pennsylvania Dental School; 22 ) CD44 (2.5 μg/ml; rat IgG2bκ, hyaluronic acid receptor) and CD138 (5.0 μg/ml; rat IgG2a,κ; syndecan-1) monoclonals (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA). After rinses (NCS/PBS, 8 minutes, four changes), sections were reacted (30 minutes, 23°C) either with peroxidase-linked secondary anti-rat IgG (6.7 μg/ml; Rockland, Inc., Gilbertsville, PA), anti-rabbit IgG (1.5 μg/ml; Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN), or anti-mouse IgGγ (10.0 μg/ml; Rockland, Inc.) antibodies, and rinsed (NCS/PBS, four changes, 12 minutes). Peroxidase activity was visualized by incubation in diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Pierce; 3 to 5 minutes). Sections were rinsed in distilled water, mounted (Aqua-mount; Lerner Laboratories, Pittsburgh, PA), and viewed with an Olympus BX60 light microscope with a Photomicrographic System PM20 (Olympus America, Inc., Lake Success, NY).

For staining with anti-Δ-heparan sulfate antibodies (5.0 μg/ml, mouse IgG2bκ heparan sulfate 3G10 epitope; antibodies react with heparitinase-digested heparan sulfate chains and HSPGs; Seikagaku Corp., Ijamsville, MD), cryosections were fixed (2% paraformaldehyde, 1 minute), and hyaluronidase treatment was replaced with heparitinase 3G10 (5.5 mU/ml; 45 minutes, 37°C; Seikagaku Corp.). NCS/PBS washes were replaced with 0.1% casein in PBS. Heparitinase treatment was omitted in negative controls.

HA staining was with b-PG, a cartilage-derived biotinylated HA-binding probe. 23 Although b-PG is specific for HA, it will only stain freely exposed HA and not HA that is masked because of interactions with proteins. For the staining, paraffin sections were incubated sequentially with b-PG (10 μg/ml), peroxidase-labeled streptavidin (1:200 dilution; Kirkegaard and Perry, Gaithersburg, MD), and a peroxidase substrate (H2O2 and 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole). 23 Counterstaining was with Mayer’s hematoxylin, and preservation with Crystal/mount (Biomeda, Hayward, CA). Background was determined by b-PG omission.

For electron microscopy, tibial growth plates from newborn wild-type control (seven samples) and Tg (line 3-2; six samples), as well as week 3 control (seven samples) and Tg mice (line 3-2; samples from three perinatal-lethal mutants and four survivors with mild disease phenotypes) were analyzed. Of these, the newborn samples were processed together, as were two batches of the week 3 mice, including both control and Tg samples in each batch. Micrographs within each figure (eg, Figures 5 to 7 ▶ ▶ ▶ ) compare simultaneously processed samples, indicating comparable tissue preservation. Processing of samples involved cutting tibiae in ∼2 × 2 × 2-mm slices, and fixing (4°C overnight) in 0.1 mol/L cacodylate buffer, pH 7.3, containing 2% glutaraldehyde, 2% paraformaldehyde, and 7% ruthenium hexamine trichloride (RHT). After rinsing (0.1 mol/L cacodylate buffer, pH 7.3, 4°C), samples were postfixed (0.1 mol/L cacodylate, pH 7.3, with 0.1% RHT; 4°C, 1 to 2 hours). After a second buffer wash, samples were either processed or stored at 4°C for 1 to 2 days. 24 Processing involved postfixation (1% osmium tetroxide, 2 hours), rinsing in buffer, staining (1% uranylacetate in maleate buffer, pH 5.2; 1 hour), rinsing in buffer, dehydrating in ethanols, clearing in propylene oxide, and embedding in Epon-Araldite (Electron Microscopy Sci., Fort Washington, PA). Thin sections of 0.5 μm were mounted on slides, stained with 1% toluidine blue, and viewed by light microscopy to assess tissue zones. Ultrathin sections of the same zones were then stained with saturated uranyl acetate in acetone (1:1, 1 minute) and 0.2% lead citrate (1 minute), and examined on a JEOL 100S electron microscope.

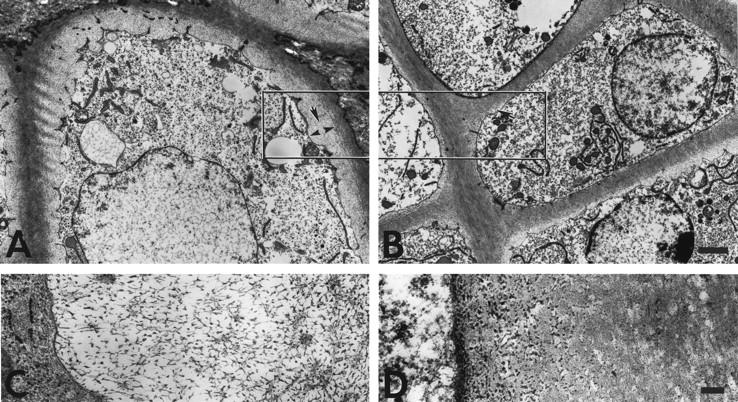

Figure 5.

Ultrastructure of hypertrophic cartilage of week 3 tibial growth plates reveals a pericellular matrix defect in collagen X Tg mice. The hypertrophic chondrocyte cell layer before the terminal layer abutting the trabecular bone and marrow is depicted. In controls, hypertrophic chondrocytes were surrounded by a gray zone corresponding to the pericellular matrix that consisted of a fine meshwork (A, arrows in boxed-in region); this matrix was reduced or lacking in the Tg mice (B, arrow). Higher magnification revealed a lattice-like array in the pericellular matrix of hypertrophic chondrocytes from controls (C). In Tg mice, no ordered networks were evident; instead, RHT-positive aggregates accumulated near cell surfaces (D). Scale bars: 2 μm (A and B); 200 nm (C and D).

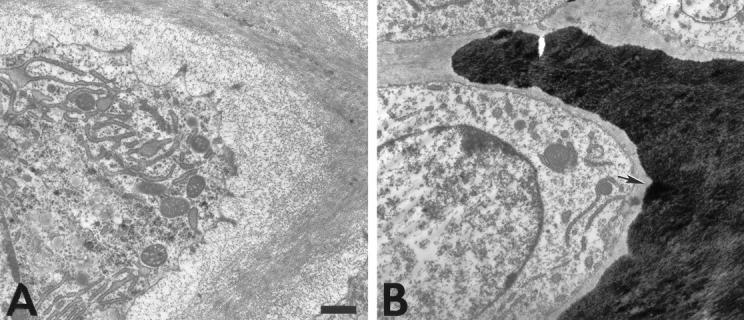

Figure 6.

Ultrastructure of hypertrophic cartilage of week 3 tibial growth plates reveals altered mineral deposition in collagen X Tg mice. The hypertrophic chondrocyte cell layer before the terminal layer abutting the trabecular bone and marrow is depicted. Occasional mineral deposits were observed adjacent to the hypertrophic chondrocyte surface in Tg mice (B, arrow), whereas these regions in controls remained mineral-free (A). Scale bars, 1 μm.

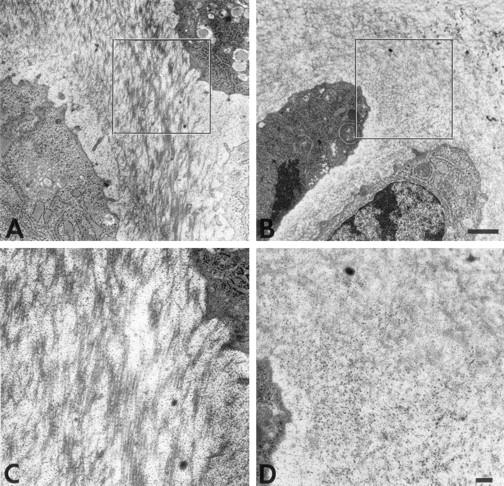

Figure 7.

Ultrastructure of proliferative cartilage of week 3 mouse tibial growth plates reveals matrix alterations in collagen X Tg mice. The territorial matrix of proliferative chondrocytes is shown. In controls (A), collagen fibrils are dispersed between a fine meshwork, likely composed of GAGs/PGs. In Tg mice (B), fibrils are difficult to distinguish because of abundant RHT-positive aggregates (dark dots). C and D: Higher magnifications of boxed-in zones in A and B, respectively. Note RHT-positive aggregates masking the collagen fibrils in D. Scale bars: 1 μm (A and B); 200 nm (C and D).

Results

Co-Expression of Truncated Chicken Collagen with Full-Length Mouse Molecules

Although collagen X is a major product of hypertrophic chondrocytes, direct protein analysis from mouse cartilage is exceedingly difficult because of limiting amounts of isolatable hypertrophic cartilage. Thus, to determine whether mutant and normal collagen X associations can occur and result in dominant interference, an in vitro cDNA expression system was used to analyze chicken transgene and wild-type mouse collagen X assembly. For this purpose, SpLX and SpLXH chicken collagen X constructs included in the Tg mice (with 21 and 293 amino acid triple-helical deletions, respectively), were expressed along with full-length mouse collagen X, mX, in a cell-free system that will perform transcription, translation, posttranslational modification, and chain assembly. 25

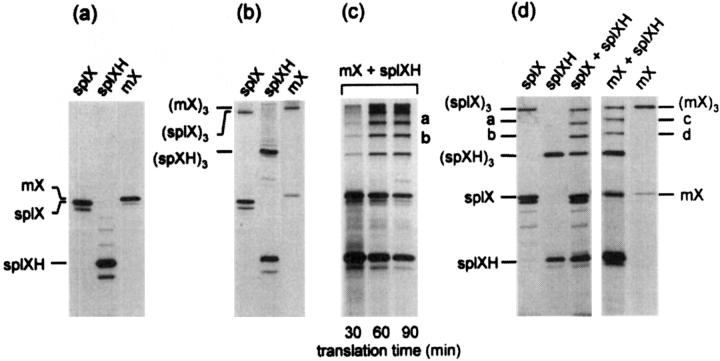

This approach demonstrated that the transgene constructs containing truncated chicken collagen X cDNA were translated into α chain monomers of molecular weight consistent with the introduced deletions, when compared to the full-length mouse chains (Figure 1a) ▶ . Under conditions favoring chain associations, assembly of truncated chicken or mouse collagen X into homotrimers was indicated by appearance of larger protein species that migrated with the expected molecular weight of the trimers (Figure 1b) ▶ . Moreover, co-translation demonstrated that mutant chicken chains could associate with each other or with mouse to form heterotrimers, as predicted by dominant interference; these associations were indicated by bands intermediate in weight between those of chicken and mouse monomers and homotrimers (Figure 1, c and d) ▶ . By varying translation time, it was established that the ratios of heterotrimer formation were constant, and that the stoichiometry of interactions between homotrimers and heterotrimers was similar and thus efficient (Figure 1c) ▶ . Last, microsomal membranes were included in the translation mix to promote translocation of the newly synthesized chains into the lumen of vesicles, and thus to provide a more physiological environment for protein interactions and folding. Under these conditions, both homotrimers and heterotrimers involving either of the chicken constructs or the full-length mouse formed efficiently (Figure 1d) ▶ . These data indicated that in vitro, transgene products and endogenous mouse collagen X were capable of forming both homotypic and heterotypic associations, yielding both chicken-mouse heterotrimers and truncated chicken homotrimers. Both of these scenarios are consistent with dominant interference.

Figure 1.

Co-expression of truncated chicken with full-length mouse collagen X chains in a cell-free translation system promotes formation of chicken and mouse homotrimers and heterotrimers. Chicken collagen X cDNAs including SpLX (21 codon deletion) and SpLXH (293-codon deletion), and mX, the full-length mouse collagen X cDNA, were transcribed and translated in a coupled cell-free translation system. Resultant [35S]-methionine-labeled products were analyzed by 7.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. a: Standard cell-free translation. Translation products from plasmids SpLX, SpLXH, and mX correspond to monomers. b: Cell-free translation under conditions favoring associations. Same samples as in a. (SpLX)3, (SpLX)3, and (mX)3 represent homotrimeric products. c: Co-translation of chicken and mouse collagen X plasmids under conditions favoring homotrimer and heterotrimer production. Trimer formation is shown as a function of translation time. Bands a and b represent the heterotrimers (mX)2(SpLXH) (band a) and (mX)(SpLXH)2 (band b). Note that with increasing translation time, stoichiometry between products remains constant. d: Cell-free co-translation of chicken and mouse collagen X plasmids in the presence of microsomal membranes. Monomers and homotrimers are as in a and b. Bands a–d represent the heterotrimers (SpLX2(SpLXH) (band a), (SpLX)(SpLXH)2 (band b), (mX)2(SpLXH) (band c), and (mX)(SpLXH)2 (band d).

Phenotypic Variability in Collagen X Tg Mice

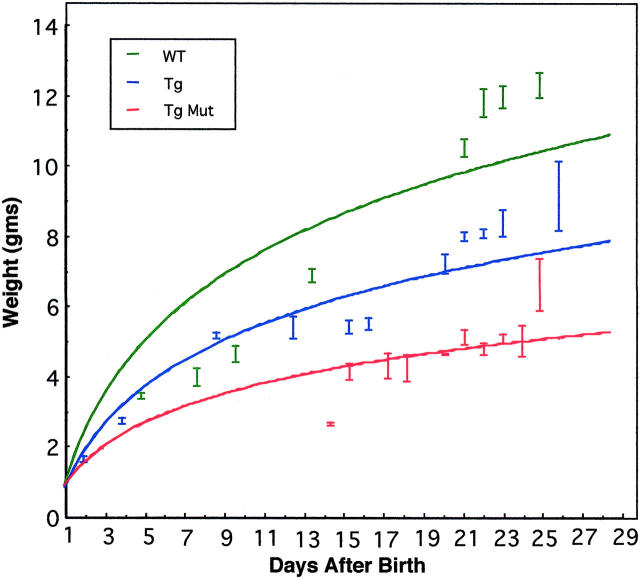

The collagen X Tg pups displayed a variable disease phenotype at approximately week 3. Specifically, ∼25% of the pups developed perinatal lethality, manifested as reduced weight (Figure 2) ▶ , wasting, and rapid death. 1,3 These mice had pronounced red marrows and lymphatic organ atrophy. The surviving ∼75% of mice exhibited dwarfism, ranging from the mice being approximately one third of the control weight, to barely distinguishable (Figure 2) ▶ . With age, this murine subset was susceptible to hematopoietic and suppressed immunity-related changes (O. Jacenko, D. Roberts, M. Campbell, P. McManus, C. Gress, and Z. Tao, submitted manuscript).

Figure 2.

Growth retardation in collagen X Tg mice. Tg mice were indistinguishable from wild-type (WT) controls at birth, but exhibited a range of defects by week 3. Variable dwarfism in ∼75% of the mice (Tg), or perinatal lethality in approximately 25% of the mice (Mut), could be detected as reduced weight. For this study, all Tg and control littermates were weighed at specified time points, and then grouped based on whether or not they developed perinatal lethality. The best-fit line program was used to generate plot.

Co-Localization of Transgene Product with Endogenous Collagen X

During the initial studies, a murine antibody against collagen X was not available, thus the localization of collagen X protein to mouse hypertrophic cartilage was inferred from in situ data, 26 and from work on other species. 27 To ensure that endogenous collagen X was co-expressed with the transgene product, a rabbit anti-mouse collagen X polyclonal antibody was generated (Materials and Methods). Antibody specificity was first confirmed by immunoblotting, in which a ∼59-kd protein was identified from a mouse cartilage extract; this band was sensitive to bacterial collagenase, after which a product of ∼20 kd remained, likely corresponding to the collagen X NC1 domain. 21

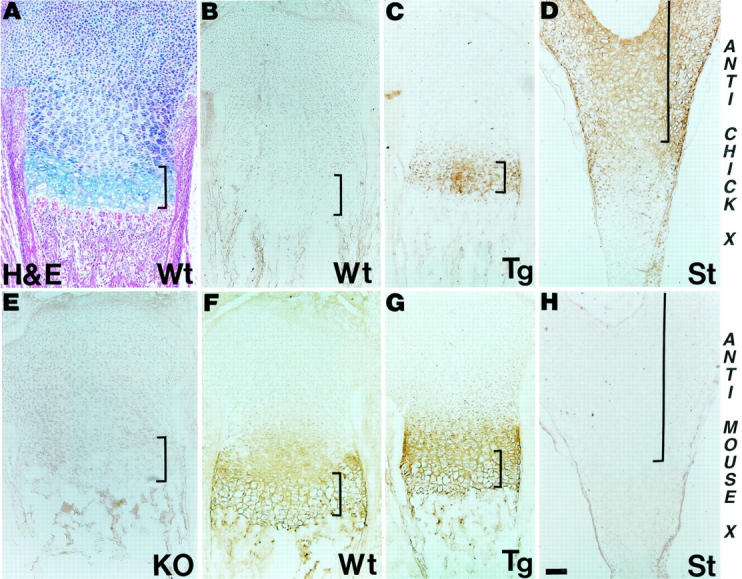

Second, cryosections of mouse brain, eyes, thymus, heart, lung, liver, spleen, kidney, skin, calvariae, and endochondral skeleton were reacted with either mouse or chicken collagen X antibodies (data not shown), which localized either mouse collagen X or the transgene product to the endochondral skeleton (Figures 3 and 4) ▶ ▶ . Above background staining was also seen in the white matter and the Purkinje cell layer of the cerebellum and the choroid layer of the eye; this staining was likely nonspecific because several antibodies used in this study yielded similar results. Moreover, brain and eye from collagen X KO mice showed similar staining (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Co-localization of transgene product with endogenous collagen X. Longitudinal tibial sections from wild-type (Wt) control, collagen X Tg (Tg), and null (KO) mice at birth, and of embryonic day 18 chick sterna (St) were either stained with H&E (A), or with antibodies against chicken (B–D) or mouse (E–H) collagen X. Note lack of cross-reactivity between chicken antibodies and mouse proteins (B), but staining of hypertrophic cartilage in Tg growth plates (C) and chick sterna (D). Mouse antibodies similarly stain hypertrophic cartilage in both WT (F) and Tg (G) mice, but do not cross-react with noncollagen X mouse proteins (E), or with chick hypertrophic cartilage (H). Faint collagen X reactivity extends into proliferative cartilage with both antibodies (C, D, F, and G). Brackets approximate width of hypertrophic cartilage. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Figure 4.

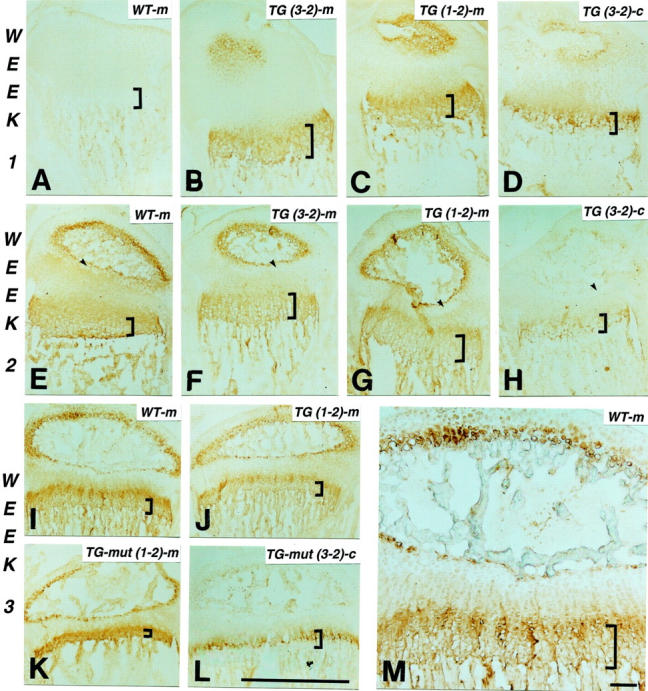

Temporal co-expression of mouse collagen X and transgene product. Longitudinal tibial sections at weeks 1 (A–D), 2 (E–H), and 3 (I–M) from wild-type control (WT; A, E, I, and M), and collagen X Tg mice from lines 3-2 [Tg (3-2) construct 1600-392 containing the 1.6-kb promotor and SpLXH cDNA with the 293-amino acid triple-helical deletion; B, D, F, H, K, and L] and 1-2 [Tg (1-2) construct 4200-21 containing the 4.2-kb promotor and SpLX cDNA with the 21-amino acid triple-helical deletion; G and J]; K and L: perinatal-lethal mutants (Tg-mut). Sections are stained with antibodies against mouse (m; B, C, E–G, I–K, and M) or chicken (c; D, H, and L) collagen X; controls include omission of primary antibodies (A). Mouse collagen X and transgene product co-localize to hypertrophic cartilage at week 1, with faint staining also in proliferative cartilage (A–D). By week 2, antibody reactivity involves hypertrophic chondrocytes within secondary ossification centers; adjacent resting cartilage (E–H, arrows) is negative. At week 3 (I–M), antibody reactivity is strongest in hypertrophic chondrocytes around secondary ossification centers, and within growth plates where it concentrates to a strip of less mature hypertrophic cells (M). Decreased trabecular bone and growth plate compressions are most pronounced in perinatal lethal mutants (K and L). Brackets approximate width of hypertrophic cartilage. Scale bars: 1 mm (A–L); 100 μm (M).

Third, tibiae from newborn mice and sterna from embryonic day 18 chicks were stained with either the chicken or mouse collagen X antibodies (Figure 3) ▶ . Chicken antibodies did not cross-react with any protein in mouse growth plates (Figure 3B) ▶ , but stained hypertrophic cartilage in Tg mice (Figure 3C) ▶ and in chick sterna (Figure 3D) ▶ . Mouse antibodies reacted with hypertrophic cartilage in control (Figure 3F) ▶ and Tg mice (Figure 3G) ▶ , but not in chick sterna (Figure 3H) ▶ . Moreover, these antibodies did not cross-react with noncollagen X proteins, because no reactivity was seen in tibiae from KO mice (Figure 3E) ▶ . In addition to the expected staining of hypertrophic cartilage, both antibodies, as well as chicken collagen X monoclonal antibodies that were previously used 3 displayed faint staining that extended into proliferative cartilage (Figure 3 ▶ ; C, D, F, and G; and Figure 4 ▶ ). This staining pattern firstly confirmed the specificity of the mouse antibodies for collagen X, and secondly demonstrated co-expression of the murine and transgene products.

Co-localization of mouse collagen X and the chicken transgene products was seen in control and Tg mice throughout several ages (Figure 4) ▶ . Specifically, at week 1 after birth, both collagen X antibodies stained hypertrophic cartilage strongly, and proliferative cartilage diffusely (Figure 4 ▶ ; A to D). With progression of EO leading to the formation of secondary ossification centers by week 2 (Figure 4 ▶ ; E to H), collagen X staining involved hypertrophic chondrocytes within ossification centers. In addition, the diffuse collagen X staining in proliferative cartilage became more distinct because of lack of reactivity in resting cartilage adjacent to the ossification centers (Figure 4 ▶ ; E to H, arrows). We had previously described 3,28 and quantitated by morphometry 1,29 the onset and extent of growth plate abnormalities in all Tg mice between weeks 2 to 3. Our immunohistochemistry has confirmed decreased trabecular bone, and growth plate compressions primarily involving hypertrophic cartilage in week 3 Tg mice (Figure 4 ▶ ; I to M); these defects were most pronounced in mutants (Figure 4, K and L) ▶ . The growth plate compressions were concomitant with the maturation of secondary ossification centers, as well as with the pups’ increased mobility and shift in weight bearing. At this age, collagen X staining was still strongest in hypertrophic chondrocytes within growth plates and secondary ossification centers. However, within growth plates, the most concentrated staining encompassed a strip of less mature hypertrophic chondrocytes separating proliferative cartilage from most mature hypertrophic cells (Figure 4M) ▶ .

Taken together, these data revealed a broader distribution of collagen X protein during long bone formation in mice. Moreover, no temporal or spatial localization differences were detected in the transgene products arising from the two different promotor lengths that were included in the transgene constructs 3 (Figure 4 ▶ ; 1-2 versus 3-2 staining patterns), thus confirming tissue specificity of the promotors at least at the protein level. These data thus confirmed the co-expression of mouse collagen X with the chicken transgene product to sites where histological defects were observed in both Tg and KO mice. 1,3,6

Ultrastructural Defects in Growth Plates Correlate with Collagen X Distribution

To establish a primary defect in hypertrophic cartilage that might result from transgene co-expression with mouse collagen X, an ultrastructural analysis was performed on growth plates from control and Tg mice. For this purpose, the cationic dye RHT was included in the fixative to precipitate PGs and thus to preserve hypertrophic cartilage matrix integrity. 30,31 In controls, hypertrophic chondrocytes were surrounded by a gray halo representing the pericellular matrix (Figure 5A ▶ , arrows), which consisted of a fine meshwork resembling a hexagonal lattice-like array (Figure 5C) ▶ similar to that formed by collagen X in vitro. 4 This network-like structure was seen in all of the control samples analyzed (eg, 7 of 7 newborn and 7 of 7 week 3). In contrast, in all Tg mice analyzed (7 of 7 newborn, 3 of 3 week 3 perinatal-lethal mutants, 4 of 4 week 3 survivors with a mild disease phenotype), the pericellular matrix surrounding the hypertrophic chondrocytes was reduced or lacking [Figure 5, B ▶ (arrow) and D]. Moreover, no ordered network-like structures were evident; instead, RHT-positive aggregates, likely GAGs and/or PGs, accumulated near cell surfaces (Figure 5D) ▶ . Occasional mineral deposits adjacent to the hypertrophic chondrocyte surface (Figure 6B) ▶ , rather than outside the pericellular matrix (Figure 6A) ▶ also suggested changes in mineral distribution. This altered mineral deposition was seen only in a fraction of the Tg mice analyzed (eg, 5 of 13 samples), but was not detected in the controls (eg, 14 of 14 samples). Furthermore, extensive RHT-positive aggregates persisted in all Tg growth plate zones including that of proliferative cartilage (Figure 7 ▶ ; seen in 7 of 7 week 3 Tg samples). It was difficult in this growth plate zone to distinguish collagen fibrils (Figure 7D) ▶ , which were distinct in controls (Figure 7, A and C) ▶ . Comparable analyses of the proliferative cartilage zone in the collagen X KO mice 6 suggested that the RHT aggregates masked the collagen fibrils, and that fibril architecture was different. These data suggest that collagen X disruption alters the matrix components within growth plates; we propose that this stems from the primary defect in hypertrophic cartilage, namely the disruption of the pericellular matrix network.

Altered GAG/PG Distribution in Growth Plates of Collagen X Tg and Null Mice

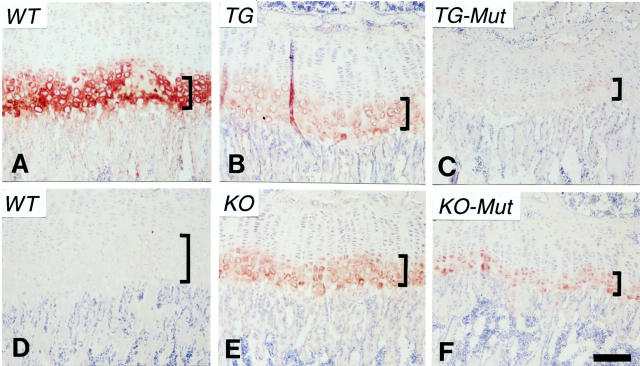

Immunohistochemistry on selected matrix molecules was performed to determine whether defects in collagen X and hypertrophic cartilage could lead to an altered distribution of other growth plate components. From a number of molecules tested, distribution differences were detected for free HA (Figure 8) ▶ and HSPG (Figure 9) ▶ . Free HA has been previously localized to the zone between the pericellular region of hypertrophic chondrocytes and their lacunae 32,33 and was thus suspected to be affected by the pericellular matrix changes in Tg mice (Figure 5) ▶ . In control growth plates, free HA was visualized as an intensely stained ring encompassing hypertrophic chondrocytes (Figure 8A) ▶ . In Tg mice with mild phenotypes (Figure 8B) ▶ and in KO mice (Figure 8, E and F) ▶ , only faint staining was seen around the hypertrophic cells. Moreover, in Tg mutants (Figure 8C) ▶ , virtually no staining for HA was detected. The distribution of CD44, the HA receptor, was primarily restricted to the marrow and trabecular bone surfaces, and was not significantly affected (data not shown).

Figure 8.

Immunohistochemical localization of HA in growth plates of wild-type and collagen X Tg and KO mice. Longitudinal sections of week 3 tibiae from wild-type controls (WT, A and D), Tg mice (TG, B), KO mice (KO, E), and Tg (TG-Mut, C) or KO (KO-Mut, F) mice exhibiting perinatal lethality. Free HA was apparent as red rings encompassing hypertrophic chondrocytes in A, whereas background staining was minimal in D. In B, E, and F, only faint staining was seen around these cells. Moreover in C, minimal staining for HA was detected. Brackets approximate width of hypertrophic cartilage. Scale bar, 100 μm.

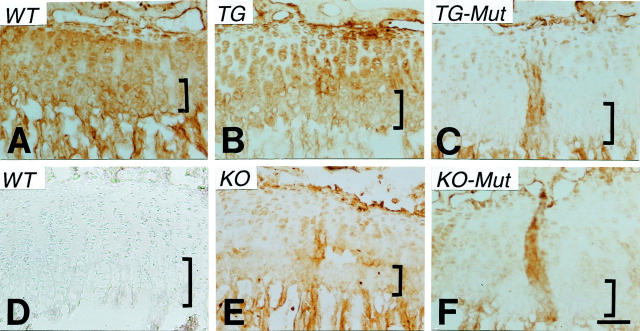

Figure 9.

Immunohistochemical localization of HSPG in growth plates of wild-type and collagen X Tg and KO mice. Longitudinal sections of week 3 tibiae from wild-type controls (WT, A and D), Tg mice (TG, B), KO mice (KO, E), and Tg (TG-Mut, C) or KO (KO-Mut, F) mice exhibiting perinatal lethality. Note HSPG localization to proliferative and hypertrophic cartilage, and to trabecular bone in A. In B, staining is pericellular in proliferative chondrocytes, and intensity is reduced in hypertrophic cartilage. In C, E, and F, staining is either faint or absent in the growth plate. D: Control where heparitinase was omitted. Brackets approximate width of hypertrophic cartilage. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Immunostaining for heparan sulfate-related epitopes was selected because of the association of HSPGs with cartilage (eg, perlecan and glypican 34,35 ), trabecular bone (eg, glypican 35 ), and marrow (glypican and syndecan 12,13,36 ). In controls, the HSPG epitope was localized to proliferative and hypertrophic cartilage growth plate zones, as well as to trabecular bone (Figure 9A) ▶ . However, in Tg mice with mild phenotypes (Figure 9B) ▶ , the staining intensity for HSPG in growth plates was reduced, and reactivity was seen as pericellular in proliferative chondrocytes, and as diffuse in the hypertrophic zone. In KO mice (Figure 9E) ▶ and in Tg and KO mutants (Figure 9, C and F ▶ , respectively), limited growth plate staining was restricted to the pericellular region of proliferative chondrocytes; hypertrophic cartilage was virtually negative, but HSPG reactivity persisted in trabecular bone. CD138/syndecan-1 staining was seen in trabecular bone and terminal hypertrophic chondrocytes, and faintly in marrow; other than for slight intensity differences, its distribution seemed unaltered in Tg and KO mice (data not shown). Taken together, these data highlight an altered distribution of HA and HSPG in growth plates of collagen X Tg and KO mice that may arise as a consequence of the changes in the hypertrophic chondrocyte pericellular matrix.

Discussion

We had previously established that the skeleto-hematopoietic phenotype in the collagen X Tg mice resulted from transgene presence, because identical defects were seen in multiple lines, each with different transgene insertions. 3 Our current data underscore and extend these findings by demonstrating that the skeleto-hematopoietic murine phenotype likely results from dominant interference of the transgene product, which co-localizes with endogenous collagen X to areas with histological defects. Moreover, we revealed a disruption of the pericellular lattice network, likely composed of collagen X, around hypertrophic chondrocytes in Tg mice, which we believe represents the primary locus of the collagen X defect. The consequent loss of structural integrity in the pericellular matrix may cause a reorganization of growth plate components, and may impact the microenvironment of the chondro-osseous and marrow junction. Toward this end, we detected an altered distribution for free HA and HSPG in growth plates of both the collagen X Tg and KO mice.

Data supporting dominant interference as a mechanism for transgene action come from use of an in vitro transcription/co-translation system. Using this approach, Bateman and co-workers 25 had demonstrated that human collagen X cDNA could be transcribed and translated into appropriate size chains that assembled into trimers, and that chain association resulted from hydrophobic interactions at NC1 domains. Moreover, they had identified the probable molecular basis of SMCD in several patients as haploinsufficiency. 16,17 Our data indicated that the transgene products and endogenous mouse collagen X molecules were capable of interacting and heterotrimerizing; likewise, truncated transgene homotrimers also formed (Figure 1) ▶ . These scenarios are both consistent with dominant interference, although cannot resolve the fate of the heterotrimers or homotrimers. As a result, it is uncertain whether dominant interference would lead to a loss-of-function for collagen X through degradation of abnormal chains, to a gain-of-function because of persistence of aberrant molecules, or to both. Comparison of growth plates from Tg and KO mice suggests that a combination of both loss and gain-of-function occurs. 1 Moreover, our data imply that synthesis of a partially functional collagen X chain that could compete for association with wild-type chains may cause a more severe phenotype through dominant interference than would haploinsufficiency, or a null allele. It is noteworthy that from more than 30 collagen X mutations identified in SMCD/SMD patients, none involve the triple helix. This suggests that a spectrum of abnormalities may ensue from mutations in different collagen X domains, as is the case with type I collagen and osteogenesis imperfecta. 37 Moreover, certain triple-helical collagen X mutations would likely yield a distinct, possibly more severe, phenotype that may include hematopoietic defects. It is noteworthy that the association of skeletal defects and dysfunction of the immune system has been recognized for a while, and that a number of immuno-osseous dysplasias, some of which resemble the murine disease phenotype, have been classified. 38-40

Co-localization of the transgene product with mouse collagen X to regions with histological defects further underscores the transgene’s specific effect on endogenous collagen X. Moreover, because transgene misexpression was not observed in other organs, especially in the lymphatics (M. Campbell, C. Gress, O. Jacenko, submitted manuscript), this scenario can be excluded as a contributor to the murine hematopoietic defects. An unresolved issue still includes the cause of the variable disease phenotype in the Tg and KO mice, which likely reflects an epigenetic phenomenon (O. Jacenko, D. Roberts, M. Campbell, P. McManus, C. Gress, and Z. Tao, submitted manuscript).

One unexpected observation concerns the broader distribution of collagen X in mouse growth plates. Namely, in addition to the expected co-localization of the transgene and endogenous collagen X to hypertrophic cartilage, proliferative cartilage exhibited faint staining. In stark contrast, resting cartilage was negative. This staining pattern was most pronounced on formation of secondary ossification centers (Figure 4) ▶ . Although it is not disputed that collagen X is synthesized predominantly by hypertrophic chondrocytes, our data are consistent with those from other groups. 41-43 Moreover, the growth plate phenotypes of the collagen X Tg and KO mice are compatible with this localization pattern, because both sets of mice also exhibit proliferative cartilage aberrations. 1,6 Cheah and co-workers 6 have proposed that collagen X partitions molecules such as matrix vesicles and PGs in hypertrophic cartilage. Our data are consistent with this hypothesis; moreover, our ultrastructural data suggest that a decompartmentalization of matrix components in Tg mice stem from a defect in the hypertrophic chondrocyte pericellular matrix.

We have observed structural differences in both hypertrophic and proliferative cartilage in Tg mice. Specifically, the hypertrophic cartilage pericellular matrix was visualized as a lattice-like network in controls, which was reduced or absent in Tg mice; instead, we detected RHT-positive aggregates, likely GAGs/PGs, accumulating near cell surfaces (Figure 5) ▶ . These aggregates persisted in proliferative cartilage of Tg mice (Figure 7) ▶ , and in KO mice. 6 Although the in vivo configuration of collagen X aggregates is still uncertain, abundant evidence implies that collagen X can assemble into a hexagonal lattice-like array. 2,4,5 This structure may be fastened by GAGs/PGs, and may stabilize hypertrophic cartilage during remodeling, as well as sequester specific molecules. Moreover, this may represent one scenario on how GAGs, PGs, and other molecules comprised in the hypertrophic chondrocyte territorial matrix may serve as a barrier to mineral deposition. The latter would be consistent with the inhibitory role of collagen X-containing matrices on mineralization, as proposed by Caplan and co-workers, 44 and would explain our detection in several Tg mice of mineral abutting the hypertrophic chondrocyte cell surface, rather than localizing outside the pericellular matrix (Figure 6) ▶ . Overall, it should be noted that gross perturbations in mineralization were not observed in the Tg mice. Previously we have reported additional minor alterations, including decreased Alizarin Red S staining of Tg sections and whole mounts 28 and subtle differences in the quality of the mineralized matrix, as observed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. 45 We believe the altered mineral deposition observed in this study represents a secondary consequence of the disrupted pericellular network in hypertrophic cartilage.

Taken together, our ultrastructural data suggest that the likely morphological consequence of collagen X perturbation by dominant interference in Tg mice is the disruption of the pericellular lattice surrounding hypertrophic chondrocytes. This disruption may ensue either from the inability of the mutant collagen X molecules to properly aggregate with the wild-type collagen, or perhaps from an increased susceptibility of the mutant chains to proteolysis. The likely consequence of the altered hypertrophic cartilage matrix is a re-distribution of GAGs/PGs, and perhaps additional molecules, in the chondro-osseous junction. Because collagen X can diffuse through cartilage and has an affinity for both PGs 42,43 and collagen fibrils 46,47 it is not surprising that the murine disease phenotype involves not only the growth plate, but the entire chondro-osseous junction and marrow.

Perhaps most noteworthy are the effects of collagen X disruption on GAG and PG distribution in both Tg and KO mice. Presence of RHT-positive aggregates throughout Tg (Figures 5 and 7) ▶ ▶ and KO 6 growth plates was the first indicator of altered GAG/PG partitioning. Because aggrecan is the predominant PG in cartilage, it is conceivable that it may be a component of these aggregates. 48 Along these lines, chondroitin sulfate was co-localized with collagen X in bovine growth plates. 41 Likewise, collagen X was reported to physically associate via the NC1 domain with sulfated PGs in cartilage. 43

Free HA was also either reduced or lacking in Tg and KO mice (Figure 8) ▶ . This GAG, typically localized between the pericellular matrix and lacunae of hypertrophic chondrocytes, has been implicated in interstitial expansion of growth plates by lacunar enlargement. 32,33 Moreover, both HA and its receptors have been associated with the assembly and retention of the chondrocyte pericellular matrix. 49 Because staining for HA was variable in our mice (Figure 8) ▶ , it is likely that HA production in hypertrophic cartilage is unaltered; HA may be leached out from tissues during fixation because of lack of retention by another matrix component. Alternatively, the reduction of free HA may globally impact growth plate integrity and function, because HA provides the backbone for PG supramolecular assembly in cartilage and thus comprises an essential component for its compressibility. Likewise, it may be noteworthy that CD44, a HA receptor, has been implicated in lymphocyte homing and adhesion during hematopoiesis; 50 this may represent a direct link between the growth plate defects and altered hematopoiesis in the marrow.

Staining for heparan sulfate also showed HSPG(s) to co-localize to a large extent with collagen X in controls, and to be reduced or absent in Tg and KO mice (Figure 9) ▶ . To identify which HSPG(s) is affected by collagen X disruption, it would be necessary to localize HSPG members in the chondro-osseous junction. Our data indicate that syndecan-1 is likely not involved, because its growth plate distribution is not significantly affected (data not shown). Alternatively, glypican and perlecan are possible candidates; both are found in cartilage that undergoes EO 34,35 and glypican is present in trabecular bone and marrow. 13,35 It is also noteworthy that inactivation of the perlecan gene in mice resulted in an acute chondrodysplasia with variable phenotypes. Approximately 50% of the mice survived until shortly after birth, and exhibited growth plate defects including disorganization of collagen fibrils and GAGs. 51 Based on the murine model, a lethal autosomal recessive human disorder termed dyssegmental dysplasia, Silverman-Handmaker type has been identified. 52

In summary, our data imply a potential association between collagen X and GAGs/PGs; this association is likely disrupted in the collagen X Tg and KO mice, causing a decompartmentalized chondro-osseous junction. Along these lines, it is noteworthy that GAGs and PGs, in particular HA and HSPGs, have been implicated as key components of marrow niches required for hematopoiesis. 11-13,53 Specifically, HSPGs are proposed to orchestrate local microenvironmental niches in the marrow by sequestering cytokines, and juxtaposing hematopoietic progenitor cells with those cytokines and the stroma to which HSPGs bind. 12 In particular, perlecan, glypican, and syndecan HSPGs were shown to be either made by stromal cells, or deposited as marrow matrix. 12,13,36 A provocative possibility links the disruption of a collagen X-containing matrix at the hypertrophic cartilage/marrow interface, to an altered GAG/PG distribution and a potential locus for hematopoietic failure in Tg and KO mice. This could be indirect through a global disruption of growth plate matrices that lead to changes in the marrow stroma, or direct by alterations in hematopoietic PGs. Support for this hypothesis would require establishing whether collagen X supramolecular aggregates require associations with specific classes of PG/GAGs for its stability and function, and if these interactions are prerequisite for hematopoiesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. B. R. Olsen (Harvard Medical School) for support and advice during the initial phases of this study, Mrs. L. Trakimas (Harvard Medical School) for assistance with electron microscopy, Dr. S. A. Apte (Cleveland Clinic) and Mr. T. Pfordte (Harvard Medical School) for mouse collagen X antibodies, Drs. B. de Crombrugghe and R. Behringer (M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, University of Texas) for the collagen X null mice, and Dr. J. D. San Antonio (Thomas Jefferson University) for critical manuscript review.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Olena Jacenko, Ph.D., University of Pennsylvania, School of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Animal Biology, 3800 Spruce St., Philadelphia, PA 19104-6046. E-mail: jacenko@vet.upenn.edu.

Supported by National Institutes of grants AR43362 and DK57904 (to O. J.).

References

- 1.Gress CJ, Jacenko O: Growth plate compressions and altered hematopoiesis in collagen X null mice. J Cell Biol 2000, 149:983-993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan D, Jacenko O: Phenotypic and biochemical consequences of collagen X mutations in mice and humans. Matrix Biol 1998, 17:1169-1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacenko O, LuValle P, Olsen BR: Spondlylometaphyseal dysplasia in mice carrying a dominant negative mutation in a matrix protein specific for cartilage-to-bone transition. Nature 1993, 365:56-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwan APL, Cummings CE, Chapman JA, Grant ME: Macromolecular organization of chicken type X collagen in vitro. J Cell Biol 1991, 114:597-604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lunstrum GP, Keene DR, Weksler NB, Cho YJ, Cornwall M, Horton WA: Chondrocyte differentiation in a rat mesenchymal cell line. J Histochem Cytochem 1999, 47:1-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwan KM, Pang MK, Zhou S, Cowen SK, Kong RY, Pfordte T, Olsen BR, Sillence DO, Tam PP, Cheah KS: Abnormal compartmentalization of cartilage matrix components in mice lacking collagen X: implications for function. J Cell Biol 1997, 136:459-471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikegawa S, Nishimura G, Nagai T, Hasegawa T, Ohashi H, Nakamura Y: Mutation in the type X collagen gene (COL10A1) causes spondylometaphyseal dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet 1998, 63:1659-1662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLaughlin SH, Conn SN, Bulleid NJ: Folding and assembly of type X collagen mutations that cause metaphyseal chondrodysplasia-type Schmid. Evidence for co-assembly of the mutant and wild-type chains and binding to molecular chaperones. J Biol Chem 1999, 274:7570-7575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lachman RS, Rimoin DL, Spranger J: Metaphyseal chondrodysplasia, Schmid type. Clinical and radiographic delineation with a review of the literature. Pediatr Radiol 1988, 18:9301-9302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savarirayan R, Cormier-Daire V, Lachman RS, Rimoin DL: Schmid type metaphyseal chondrodysplasia: a spondylometaphyseal dysplasia identical to the “Japanese” type. Pediatr Radiol 2000, 30:460-463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruno E, Luikart SD, Long MW, Hoffman R: Marrow-derived heparan sulfate proteoglycan mediates the adhesion of hematopoietic progenitor cells to cytokines. Exp Hematol 1995, 23:1212-1217 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta P, Oegama TRJ, Brazil JJ, Dudek AZ, Slungaard A, Verfaille CM: Structurally specific heparan sulfate supports primitive human hematopoiesis by formation of a multimolecular stem cell niche. Blood 1998, 92:4641-4651 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siebertz B, Stocker G, Drzeniek Z, Handt S, Just U, Haubeck HD: Expression of glipican-4 in haematopoietic progenitor and bone marrow stromal cells. Biochem J 1999, 344:937-943 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Apte SS, Olsen BR: Characterization of the mouse type X collagen gene. Matrix 1993, 13:165-179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T: Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 1989. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor

- 16.Chan D, Weng YM, Graham HK, Sillence DO, Bateman JF: A nonsense mutation in the carboxyl-terminal domain of the type X collagen causes haploinsufficiency in Schmid metaphyseal chondrodysplasia. J Clin Invest 1998, 101:1490-1409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan D, Freddi S, Weng YM, Bateman JF: Interaction of collagen α(X) containing engineered NC1 mutations with normal α(X) in vitro. J Biol Chem 1999, 274:13091-13097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan D, Cole WG, Rogers JG, Bateman JF: Type X collagen multimer assembly in vitro is prevented by a Gly 618 to Val mutation in the alpha 1(X) NC1 domain resulting in Schmid metaphyseal chondrodysplasia. J Biol Chem 1995, 270:4558-4562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosati R, Horan GS, Pinero GJ, Garofalo S, Keene DR, Horton WA, Vuorio E, de Crombrugghe B, Behringer RR: Normal long bone growth and development in type X collagen null mice. Nat Genet 1994, 8:129-135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koerner TJ, Hill JE, Myers AM, Tzageloff A: High-expression vectors with multiple cloning sites for construction of trpE-fusion genes: pATH vectors. Methods Enzymol 1990, 194:477-490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfordte T: Production and characterization of a polyclonal mouse type X collagen antibody. 1994:pp 51 Harvard Medical School, Department of Cell Biology, Boston

- 22.Pacifici M, Golden EB, Iwamoto M, Adams SL: Retinoic acid treatment induces type X collagen gene expression in cultured chick chondrocytes. Exp Cell Res 1991, 195:38-46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green SJ, Tarone G, Underhill CB: Distribution of hyaluronate and hyaluronate receptors in the adult lung. J Cell Sci 1988, 89:145-156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farnum CE, Wilsman NJ: Morphologic stages of the terminal hypertrophic chondrocyte of the growth plate cartilage. Anat Rec 1987, 219:221-232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan D, Lamande SR, McQuillan DJ, Bateman JF: In vitro expression and analysis of collagen biosynthesis and assembly. J Biochem Biophys Methods 1997, 36:11-29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kong RYC, Kwan KM, Sau ET, Thomas JT, Boot-Handford RP, Grant ME, Cheah KSE: Intron-exon structure, alternative use of the promotor and expression of the mouse collagen X gene, COL1OA1. Eur J Biochem 1993, 213:99-111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linsenmayer TF, Chen QA, Gibney E, Gordon MK, Marchant JK, Mayne R, Schmid TM: Collagen types IX and X in the developing chick tibiotarsus: analysis of mRNAs and proteins. Development 1991, 111:191-196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacenko O, LuValle P, Solum K, Olsen BR: A dominant negative mutation in the α1(X) collagen gene produces spondylometaphyseal defects in mice. Progress in Clinical and Biological Research: Limb Development and Regeneration. 1993, :pp 427-436 Wiley-Liss, New York [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacenko O, Ito S, Olsen BR: Skeletal and hematopoietic defects in mice transgenic for collagen X. Ann NY Acad Sci 1996, 785:278-280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hunziker EB, Herrman W, Schenk RK: Improved cartilage fixation by ruthenium hexamine trichloride (RHT). A prerequisite for morphometry in growth cartilage. J Ultrastruct Res 1982, 81:1-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunziker EB, Herrmann W, Schenk RK: Ruthenium hexamine trichloride (RHT)-mediated interaction between plasmalemmal components and pericellular matrix proteoglycans is responsible for the preservation of chondrocytic plasma membranes in situ during cartilage fixation. J Histochem Cytochem 1984, 31:717-727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pavasant P, Shizari TM, Underhill CB: Distribution of hyaluronan in the epiphyseal growth plate: turnover by CD44-expressing osteoprogenitor cells. J Cell Sci 1994, 107:2669-2677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pavasant P, Shizari T, Underhill CB: Hyaluronan contributes to the enlargement of hypertrophic lacunae in the growth plate. J Cell Sci 1996, 109:327-334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Handler M, Yurchenco PD, Iozzo RV: Developmental expression of perlecan during murine embryogenesis. Dev Dyn 1997, 210:130-145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Litwack ED, Ivins JK, Kumbasar A, Paine-Saunders S, Stipp CS, Lander AD: Expression of the heparan sulfate proteoglycan glypican-1 in the developing rodent. Dev Dyn 1998, 211:72-87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kincade PW, Yamashita Y, Borghesi L, Medina K, Oritani K: Blood cell precursors in context. Composition of the bone marrow microenvironment that supports B lymphopoiesis. Vox Sang 1998, 74(Suppl):S265-S268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuivaniemi H, Tromp G, Prockop DJ: Mutations in fibrillar collagens (types I, II, III, and XI), fibril-associated collagen (type IX), and network-forming collagen (type X) cause a spectrum of diseases of bone, cartilage, and blood vessels. Hum Mutat 1997, 9:300-315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Castriota-Scanderbeg A, Mingarelli R, Caramia G, Osimani P, Lachman RS, Rimoin DL, Wilcox WR, Dallapiccola B: Spondylo-mesomelic-acrodysplasia with joint dislocations and severe combined immunodeficiency: a newly recognized immuno-osseous dysplasia. J Med Genet 1997, 34:854-856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spranger J, Hinkel GK, Stoss H, Thoenes W, Wargowski D, Zepp F: Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia: a newly recognized multisystem disease. J Pediatr 1991, 119:64-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cederbaum SD, Kaitila I, Stiehm ER: The chondro-osseous dysplasia of adenosine deaminase deficiency with severe combined immunodeficiency. J Pediatr 1976, 89:737-742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gibson G, Lin DL, Francki K, Caterson B, Foster B: Type X collagen is colocalized with a proteoglycan epitope to form distinct morphological structures in bovine growth cartilage. Bone 1996, 19:307-315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen QA, Gibney E, Fitch J, Linsenmayer C, Schmid TM, Linsenmayer TF: Long-range movement and fibril association of type X collagen within embryonic cartilage matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990, 87:8046-8050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Q, Linsenmayer C, Gu H, Schmid TM, Linsenmayer TF: Domains of type X collagen: alteration of cartilage matrix by fibril association and proteoglycan accumulation. J Cell Biol 1992, 117:687-694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arias JL, Nakamura O, Fernandez MS, Wu JJ, Knigge P, Eyre DR, Caplan AI: Role of type X collagen on experimental mineralization of eggshell membranes. Connect Tissue Res 1997, 36:21-33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paschalis EP, Jacenko O, Olsen BR, Mendelsohn R, Boskey AL: FT-IR microscopic analysis identifies alterations in mineral properties in bones from mice transgenic for collagen X. Bone 1996, 19:151-156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poole AR, Pidoux I: Immunoelectron microscopic studies of type X collagen in endochondral ossification. J Cell Biol 1989, 109:2547-2554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmid T, Linsenmayer T: Immunoelectron microscopy of type X collagen: supramolecular forms within embryonic chick cartilage. Dev Biol 1990, 138:53-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Comper WD: Physicochemical aspects of cartilage extracellular matrix. Hall B Newman SA eds. Cartilage: Molecular Aspects, 1991, vol 3.:pp 59-78 CRC Press, Boca Raton [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knudson CB, Knudson W: Hyaluronan-binding proteins in development, tissue homeostasis, and disease. FASEB J 1993, 7:1233-1241 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gunthert U: CD44: a multitude of isoforms with diverse functions. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 1993, 184:47-63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arikawa-Hirasawa E, Watanabe H, Takami H, Hassell JR, Yamada Y: Perlecan is essential for cartilage and cephalic development. Nat Genet 1999, 23:354-358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arikawa-Hirasawa E, Wilcox WR, Le AH, Silverman N, Govindraj P, Hassell JR, Yamada Y: Dyssegmental dysplasia, Silverman-Handmaker type, is caused by functional null mutations of the perlecan gene. Nat Genet 2001, 27:431-434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gupta P, McCarthy JB, Verafaillie CM: Stromal fibroblasts heparan sulfate is required for cytokine-mediated ex vivo maintenance of human long-term culture-initiating cells. Blood 1996, 87:3229-3236 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]