Abstract

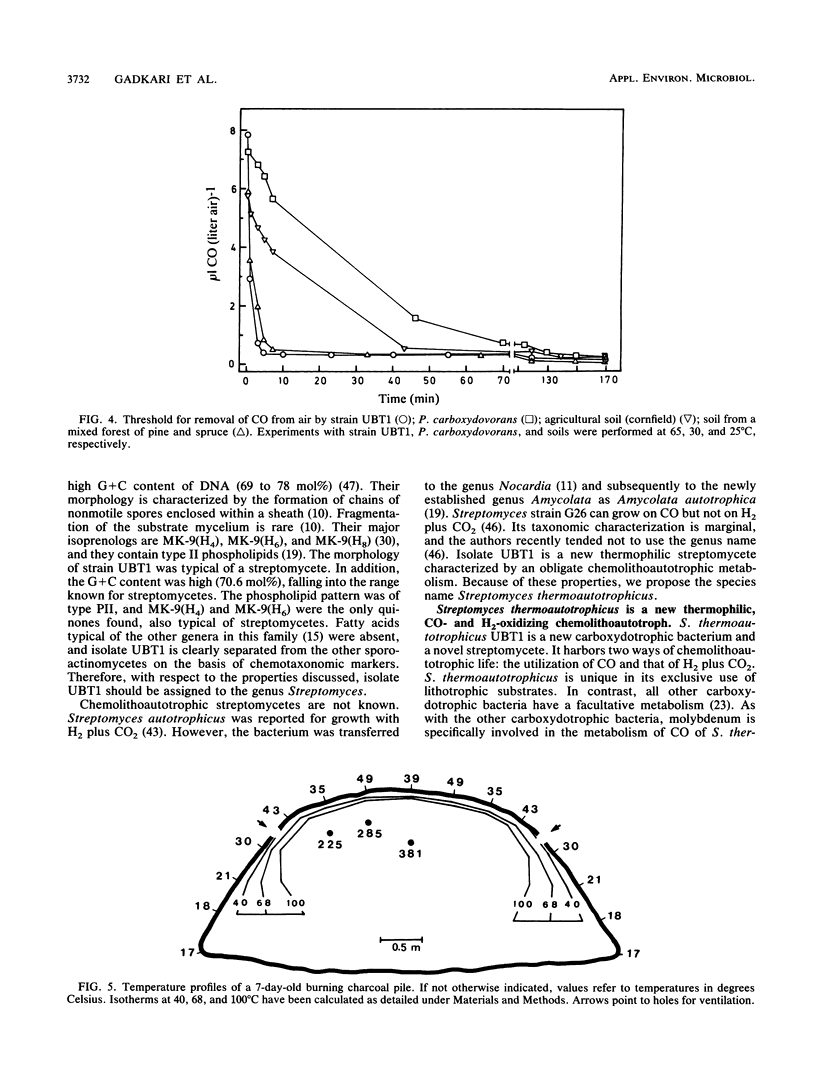

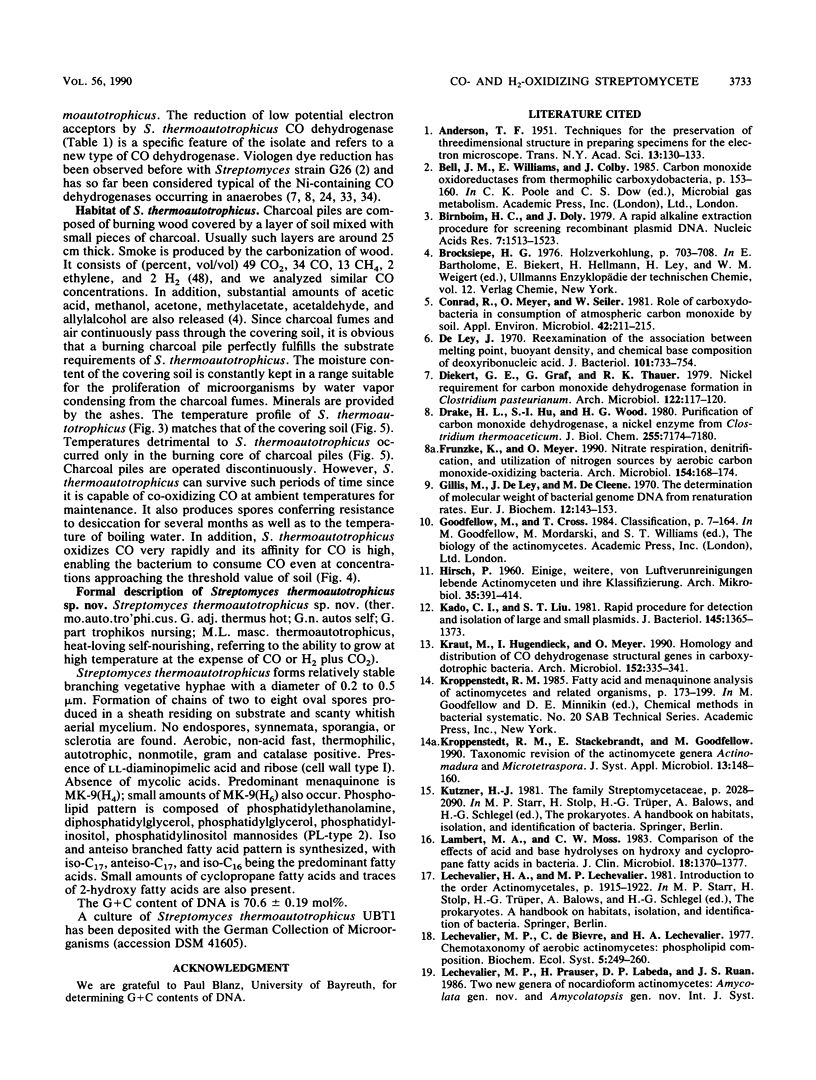

The novel thermophilic CO- and H2-oxidizing bacterium UBT1 has been isolated from the covering soil of a burning charcoal pile. The isolate is gram positive and obligately chemolithoautotrophic and has been named Streptomyces thermoautotrophicus on the basis of G+C content (70.6 ± 0.19 mol%), a phospholipid pattern of type II, MK-9(H4) as the major quinone, and other chemotaxonomic and morphological properties. S. thermoautotrophicus could grow with CO (td = 8 h), H2 plus CO2 (td = 6 h), car exhaust, or gas produced by the incomplete combustion of wood. Complex media or heterotrophic substrates such as sugars, organic acids, amino acids, and alcohols did not support growth. Molybdenum was required for CO-autotrophic growth. For growth with H2, nickel was not necessary. The optimum growth temperature was 65°C; no growth was observed below 40°C. However, CO-grown cells were able to oxidize CO at temperatures of 10 to 70°C. Temperature profiles of burning charcoal piles revealed that, up to a depth of about 10 to 25 cm, the entire covering soil provides a suitable habitat for S. thermoautotrophicus. The Km was 88 μl of CO liter−1 and Vmax was 20.2 μl of CO h−1 mg of protein−1. The threshold value of S. thermoautotrophicus of 0.2 μl of CO liter−1 was similar to those of various soils. The specific CO-oxidizing activity in extracts with phenazinemethosulfate plus 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol as electron acceptors was 246 μmol min−1 mg of protein−1. In exception to other carboxydotrophic bacteria, S. thermoautotrophicus CO dehydrogenase was able to reduce low potential electron acceptors such as methyl and benzyl viologens.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Birnboim H. C., Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979 Nov 24;7(6):1513–1523. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad R., Meyer O., Seiler W. Role of carboxydobacteria in consumption of atmospheric carbon monoxide by soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981 Aug;42(2):211–215. doi: 10.1128/aem.42.2.211-215.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ley J. Reexamination of the association between melting point, buoyant density, and chemical base composition of deoxyribonucleic acid. J Bacteriol. 1970 Mar;101(3):738–754. doi: 10.1128/jb.101.3.738-754.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake H. L., Hu S. I., Wood H. G. Purification of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase, a nickel enzyme from Clostridium thermocaceticum. J Biol Chem. 1980 Aug 10;255(15):7174–7180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis M., De Ley J., De Cleene M. The determination of molecular weight of bacterial genome DNA from renaturation rates. Eur J Biochem. 1970 Jan;12(1):143–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1970.tb00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIRSCH P. [Some additional Actinomycetes existing on air impurities and their classification]. Arch Mikrobiol. 1960;35:391–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kado C. I., Liu S. T. Rapid procedure for detection and isolation of large and small plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1981 Mar;145(3):1365–1373. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.3.1365-1373.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraut M., Hugendieck I., Herwig S., Meyer O. Homology and distribution of CO dehydrogenase structural genes in carboxydotrophic bacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1989;152(4):335–341. doi: 10.1007/BF00425170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert M. A., Moss C. W. Comparison of the effects of acid and base hydrolyses on hydroxy and cyclopropane fatty acids in bacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 1983 Dec;18(6):1370–1377. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.6.1370-1377.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer O. Chemical and spectral properties of carbon monoxide: methylene blue oxidoreductase. The molybdenum-containing iron-sulfur flavoprotein from Pseudomonas carboxydovorans. J Biol Chem. 1982 Feb 10;257(3):1333–1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer O., Schlegel H. G. Biology of aerobic carbon monoxide-oxidizing bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1983;37:277–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.37.100183.001425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer O., Schlegel H. G. Reisolation of the carbon monoxide utilizing hydrogen bacterium Pseudomonas carboxydovorans (Kistner) comb. nov. Arch Microbiol. 1978 Jul;118(1):35–43. doi: 10.1007/BF00406071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L. T. Single derivatization method for routine analysis of bacterial whole-cell fatty acid methyl esters, including hydroxy acids. J Clin Microbiol. 1982 Sep;16(3):584–586. doi: 10.1128/jcm.16.3.584-586.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnikin D. E., Alshamaony L., Goodfellow M. Differentiation of Mycobacterium, Nocardia, and related taxa by thin-layer chromatographic analysis of whole-organism methanolysates. J Gen Microbiol. 1975 May;88(1):200–204. doi: 10.1099/00221287-88-1-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REYNOLDS E. S. The use of lead citrate at high pH as an electron-opaque stain in electron microscopy. J Cell Biol. 1963 Apr;17:208–212. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.1.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale S. W., Clark J. E., Ljungdahl L. G., Lundie L. L., Drake H. L. Properties of purified carbon monoxide dehydrogenase from Clostridium thermoaceticum, a nickel, iron-sulfur protein. J Biol Chem. 1983 Feb 25;258(4):2364–2369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale S. W., Ljungdahl L. G., DerVartanian D. V. Isolation of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase from Acetobacterium woodii and comparison of its properties with those of the Clostridium thermoaceticum enzyme. J Bacteriol. 1983 Sep;155(3):1224–1237. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.3.1224-1237.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staneck J. L., Roberts G. D. Simplified approach to identification of aerobic actinomycetes by thin-layer chromatography. Appl Microbiol. 1974 Aug;28(2):226–231. doi: 10.1128/am.28.2.226-231.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKAMIYA A., TUBAKI K. A new form of Streptomyces capable of growing autotrophically. Arch Mikrobiol. 1956;25(1):58–64. doi: 10.1007/BF00424890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub W. H., Acker G., Kleber I. Ultrastructural surface alterations of serratia marcescens after exposure to polymyxin B and/or fresh human serum. Chemotherapy. 1976;22(2):104–113. doi: 10.1159/000221919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine R. C., Shapiro B. M., Stadtman E. R. Regulation of glutamine synthetase. XII. Electron microscopy of the enzyme from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1968 Jun;7(6):2143–2152. doi: 10.1021/bi00846a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams E., Colby J. Biotechnological applications of carboxydotrophic bacteria. Microbiol Sci. 1986 May;3(5):149–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]