Abstract

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) contributes to liver injury by inducing hepatocyte apoptosis. Recent evidence suggests that cathepsin B (cat B) contributes to TNF-α-induced apoptosis in vitro. The aim of the present study was to determine whether cat B contributes to TNF-α-induced hepatocyte apoptosis and liver injury in vivo. Cat B knockout (catB−/−) and wild-type (catB+/+) mice were first infected with the adenovirus Ad5IκB expressing the IκB superrepressor to inhibit nuclear factor-κB-induced survival signals and then treated with murine recombinant TNF-α. Massive hepatocyte apoptosis with mitochondrial release of cytochrome c and activation of caspases 9 and 3 was detected in catB+/+ mice 2 hours after the injection of TNF-α. In contrast, significantly less hepatocyte apoptosis and no detectable release of cytochrome c or caspase activation occurred in the livers of catB−/− mice. By 4 hours after TNF-α injection, only 20% of the catB+/+ mice were alive as compared to 85% of catB−/− mice. Pharmacological inhibition of cat B in catB+/+ mice with l-3-trans-(propylcarbamoyl)oxirane-2-carbonyl-l-isoleucyl-l-proline (CA-074 Me) also reduced TNF-α-induced liver damage. The present data demonstrate that a cat B-mitochondrial apoptotic pathway plays a pivotal role in TNF-α-induced hepatocyte apoptosis and liver injury.

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) is an inflammatory cytokine that activates a wide array of cellular signaling pathways including mitogenic responses and cell death by apoptosis. 1 In a wide variety of inflammatory liver diseases, TNF-α has been implicated as a key cytotoxin. 2 Indeed, TNF-α-mediated hepatocyte injury has been implicated in alcoholic hepatitis, nonalcoholic hepatitis, ischemia/reperfusion injury, viral hepatitis, and fulminant hepatic failure of several etiologies. 3-6 Thus, the cell signaling pathways by which TNF-α induces hepatocyte injury is of fundamental scientific and clinical interest. Information on signaling of apoptosis by this cytokine has the potential to lead to therapeutic strategies for the treatment of inflammatory human liver diseases.

Cytotoxic responses by TNF-α are elicited after ligand binding to the TNF-receptor 1 (TNF-R1). 1 Cell signaling by this receptor is extremely complex and includes activation of a caspase 8-mediated apoptosis pathway and a nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)-dependent survival pathway. 7 The predominant response to TNF-α, cell survival or cell death, depends on the cell context. In regard to cell context and the liver, several pathophysiological conditions have now been identified that predispose the hepatocyte to cell death. 8,9 In hepatocytes, the proximal cytotoxic response after TNF-R1 oligomerization by TNF-α involves caspase 8 activation. 10 Activated caspase 8 initiates a complex sequence of signaling events resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction, 11 ceramide generation, 12 and activation of downstream caspases. 13,14 The mitochondrial dysfunction allows cytochrome c, a mitochondrial protein involved in electron transfer and located in the intermembrane space, to be released into the cytosol. Cytosolic cytochrome c binds to the apoptosis activating factor-1 (Apaf-1), forming a protein complex that recruits procaspase 9, resulting in its activation. 11 Caspase 9 activates caspase 3, initiating a caspase cascade that leads to cell death. 13,14 Recently, a cytotoxic pathway involving acidic vesicles has also been identified in TNF-α-mediated cell death. 15 We have recently extended these findings by demonstrating that in cell culture systems, caspase 8 activation is associated with the release of cat B, a cysteine protease, from acidic vesicles into the cytosol. 16 In the presence of cytosol, cat B was found to induce mitochondrial release of cytochrome c and activation of caspase 9 and 3. The importance of this pathway in TNF-α-mediated apoptosis in vitro was shown by demonstrating that hepatocytes isolated from cat B knock out mice (catB−/−) mice are resistant to TNF-α-induced apoptosis. 16 More recently, Foghsgaard and colleagues 17 also have demonstrated a dominant role for cat B in TNF-α-mediated apoptosis. Indeed, in a murine tumor cell line, caspase inhibition actually accentuated TNF-α-induced apoptosis by a cat B pathway. Thus, interruption of this signaling pathway is a potential new pharmacological target for inhibiting TNF-α-mediated liver injury.

Based on these observations, we sought to verify in the present study whether catB−/− mice are more resistant to TNF-α-mediated hepatocyte apoptosis and liver injury in vivo. We used a model of liver injury using intravenous injection of TNF-α combined with infection with a recombinant adenovirus construct expressing an IκB superrepressor (Ad5IκB). 18 The IκB superrepressor inhibits activation of NF-κB-dependent survival pathway unmasking the cytotoxicity of TNF-α. 19

Materials and Methods

Animal Model and Experimental Paradigm

CatB−/− mice were generated as previously reported. 20 Littermate wild-type mice (CatB+/+) were used as controls. Animals were cared for using protocols reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Mayo Clinic. The recombinant replication-deficient adenovirus Ad5IκB expressing the IκB superrepressor and the adenovirus Ad5ΔE1, an empty virus used for control experiments, were generous gifts of Dr. David Brenner (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC). The viruses were grown and purified by banding twice in CsCl gradients as previously described. 21 The Ad5IκB superrepressor, the Ad5ΔE1 (both 3.2 × 10 9 pfu/ml in 0.22 ml of sterile saline), or sterile saline (0.22 ml), was injected into the mice via the tail vein. The Ad5IκB concentration used was chosen after preliminary experiments demonstrated its low toxicity and its effectiveness in sensitizing the mice to TNF-α-induced liver injury (data not shown). Twenty-four hours after the viral injection, mice were injected intravenously with murine recombinant TNF-α in pyrogen-free saline (0.5 μg/mouse). To obtain pharmacological inhibition of cat B, wild-type mice were given an intraperitoneal injection of 0.9 ml of saline containing l-3-trans-(propylcarbamoyl)oxirane-2-carbonyl-l-isoleucyl-l-proline (CA-074 Me) (4 mg/100g) or 0.9 ml of saline only (controls), 30 minutes before the injection of TNF-α. Mice were killed by exsanguination under deep anesthesia 2 and 4 hours after the injection of TNF-α. The peritoneal cavity was opened, blood samples were taken from the intrahepatic vena cava, followed by immediate cannulation of the suprahepatic vena cava with a 20-gauge catheter. After the catheter was secured with 5-0 silk ligatures, the portal vein was cut. Using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 137 mmol/L NaCl, 2.7 mmol/L KCl, 8 mmol/L Na2HPO4·7H2O, 1.5 mmol/L/L KH2PO4, pH 7.4), blood was flushed out of the liver via the suprahepatic vena cava catheter. The liver was cut into small pieces and either snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C, or fixed in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 24 hours at 4°C for histological/immunohistochemical analysis and for the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay. Fresh samples were also used for preparation of whole-cell lysates and subcellular fractions for immunoblot analysis.

Histological Analysis

The tissue blocks were embedded in Tissue Path (Curtin Matheson Scientific Inc., Houston, TX). Tissue sections (4 μm) were prepared using a microtome (Reichert Scientific Instruments, Buffalo, NY) and placed on glass slides. The sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated with ethanol series and water, and washed in PBS. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed on the sections using standard techniques.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunoreactivity for NF-κB and active caspase 3/7 was evaluated as previously described by us. 22,23 Briefly, the sections first were incubated for 20 minutes in 3% H2O2 in methanol to block the endogenous peroxidase activity, and then treated with 0.2% horse serum (for NF-κB) or goat serum (for caspase 3/7) in PBA buffer (0.3% Triton X-100, 0.5% bovine serum albumin, in PBS, pH 7.4) for 20 minutes at room temperature, to block nonspecific binding and permeabilize the tissue. The blocking of nonspecific biotin binding was then performed using a commercially available blocking kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The tissue sections were incubated with a mouse monoclonal antibody recognizing the p65 subunit of NF-κB (F-6; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) or with CM1 rabbit polyclonal antibody recognizing a common neoepitope shared by activated caspase 3 and caspase 7 (a kind gift of Dr. Anu Srinivasan, IDUN Pharm., La Jolla, CA) 24 at a concentration of 4 μg/ml and 5.5 μg/ml, respectively (dilution 1:50 and 1:100, respectively), in PBS with 0.5% bovine serum albumin for 1 hour at room temperature. The immunoreactivity for NF-κB or active caspase 3/7 was visualized with the Vectastain peroxidase kit (Vector Laboratories) using diluted biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG (for NF-κB) or goat anti-rabbit IgG (for caspase 3/7), and developed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrachloride for 3 to 5 minutes at room temperature. Immunostained sections were counterstained with eosin for 15 minutes and evaluated by light microscopy.

TUNEL Assay

The sections were incubated with 20 μg/ml proteinase K in 10 mmol/L of Tris/HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 5 mmol/L of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, for 30 minutes at 37°C, and washed twice in distilled water. In situ labeling of apoptosis-induced DNA strand breaks (TUNEL assay) was performed using a commercially available kit (In Situ Cell Death Detection kit; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN). The number of TUNEL-positive cells (ie, fluorescent nuclei) were counted in 36 random microscopic high-power fields using an inverted laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510, Carl Zeiss Inc, Thornwood, NJ).

Preparation of Subcellular Fractions

Cytosolic extracts (S-100) were prepared from mouse liver using the approach described by Yang and colleagues 25 and slightly modified by us. Briefly, freshly isolated liver samples were placed on ice in 5 vol of buffer A (250 mmol/L sucrose, 20 mmol/L HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 10 mmol/L KCl, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 1 mmol/L EGTA, 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol, and 0.1 mmol/L phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride), subjected to 20 strokes of homogenization in a Dounce homogenizer with a loose-fitting pestle, and intact cells, nuclei, and debris were pelleted by two consecutive centrifugations at 750 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatants were then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C and the resulting pellets (mitochondria) resuspended in 200 μl of buffer A and stored at −80°C. Supernatants were further centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 hour at 4°C, and the final supernatants (designated S-100) were divided into aliquots and stored at −80°C. Protein concentration was measured using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Preparation of Whole-Cell Lysates

Liver protein extracts from whole-cell lysates were prepared as follows: fresh liver samples of ∼500 mg were lysed in 1 ml of RIPA buffer (10 mmol/L HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 10% glycerol, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 0.1 mmol/L phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride) and homogenized on ice using a glass Dounce homogenizer with tight pestle. The homogenates were then subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles, each one consisting of a 4-minute incubation on ethanol/dry ice and a 4-minute incubation at 37°C, with a 15 second-vortex between each cycle, and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The supernatants were saved and stored in aliquots at −20°C.

Immunoblot Analysis

Aliquots of S-100 cytosolic extracts containing 60 μg of protein were subjected to 15% sodium dodecyl sulfatepolyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After nonspecific binding was blocked by incubation with 5% (w/v) skim milk in T-TBS (20 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.0, 0.15 mol/L NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) for 1 hour at room temperature, membranes were probed overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: mouse anti-cytochrome c (PharMingen, San Diego, CA), dilution 1:1000; rabbit antiserum recognizing a neoepitope at the carboxyl terminus of the large subunit of the active caspase 9 (a kind gift from Dr. Scott Kaufmann, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), 26 dilution 1:100; CM1 rabbit anti-active caspase 3, dilution 1:5000; goat anti-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), dilution 1:2500. Membranes were then incubated with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies diluted 1:4000 in 3% skim milk in T-TBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Blots were developed by the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

For the analysis of the expression of TNF-R1, aliquots of whole-cell lysates containing 60 μg of protein were subjected to 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and probed with a mouse anti-TNF-R1 (H-5; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), dilution 1:1000, using the procedure described above.

Determination of Serum Alanine Aminotransferase Activity

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level was measured using a commercially available assay kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO).

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM from at least three separate experiments. Differences between groups were compared using an analysis of variance for repeated measures and a post hoc Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons. Statistical analysis was performed using Instat Software (Graph-PAD, San Diego, CA).

Reagents

Peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG, goat anti-mouse IgG, and swine anti-goat IgG were from Biosource International (Camarillo, CA). Proteinase K was from Boehringer Mannheim. CA-074 Me was from Peptide Institute Inc. (Osaka, Japan). Mouse recombinant TNF-α, phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride, aprotinin, pepstatin, leupeptin, and all other chemicals were from Sigma Chemical Co.

Results

Is TNF-α-Induced Hepatocyte Apoptosis Reduced in CatB−/− Mice?

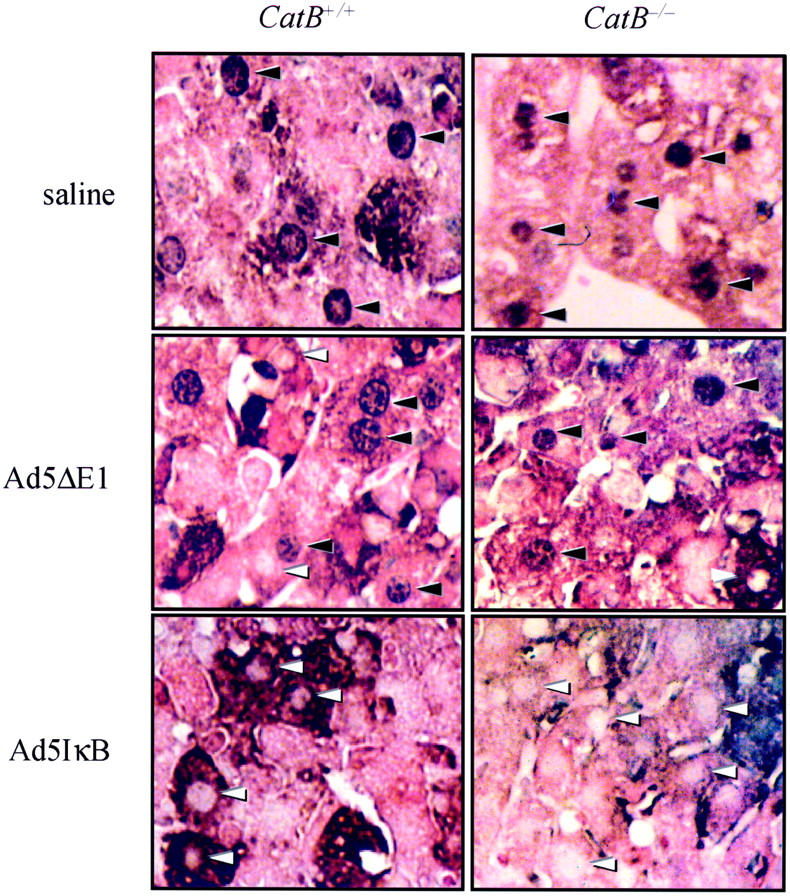

Mice were sensitized to TNF-α-toxicity by inhibiting NF-κB activation and translocation to the nucleus via infection with the Ad5IκB adenovirus construct expressing the IκB superrepressor. 19 In mice receiving the control vector Ad5ΔE1 or saline, TNF-α treatment caused translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus (Figure 1) ▶ . In contrast, in mice infected with the Ad5IκB, NF-κB remained cytosolic in its localization after TNF-α treatment. These data confirmed that NF-κB is effectively inhibited by the Ad5IκB expression system in mice.

Figure 1.

Infection with the adenovirus Ad5IκB effectively prevents NF-κB translocation to the nucleus in mouse hepatocytes. Wild-type and catB−/− mice were injected via tail vein with the adenovirus Ad5IκB encoding for an IκB superrepressor. In control experiments, mice were injected with the empty adenovirus Ad5ΔE1 or with sterile saline. Twenty-four hours later, each mouse received a dose of 0.5 μg of murine recombinant TNF-α intravenously. Mice were killed after 2 hours of treatment with TNF-α, and immunohistochemistry for NF-κB was performed on paraffin-embedded tissue. Hepatocyte nuclei from control animals showed strongly positive staining for NF-κB (black arrowheads). Inhibition of NF-κB translocation from the cytosol to the nucleus was confirmed by the lack of immunohistochemical staining for NF-κB in the nuclei of both catB+/+ and catB−/− in mice infected with Ad5IκB (white arrowheads).

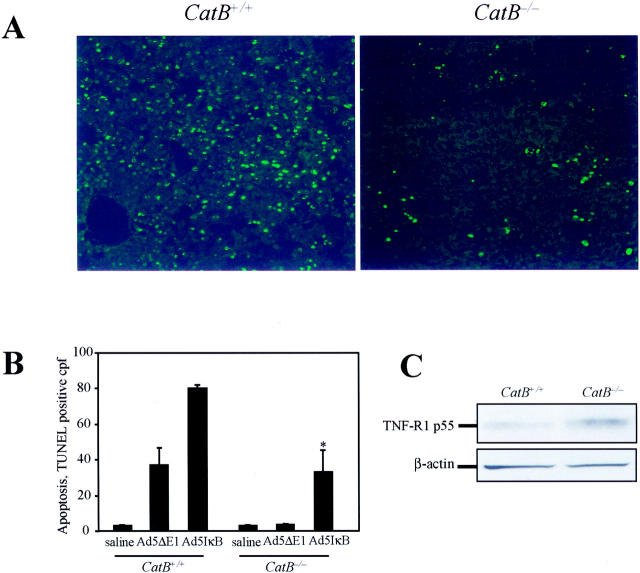

Hepatocyte apoptosis was next quantitated using the TUNEL assay. Liver specimens from Ad5IκB-infected mice collected 2 hours after injection of TNF-α showed massive hepatocyte apoptosis in catB+/+ mice, whereas significantly less apoptosis occurred in catB−/− livers (80.1 ± 3 versus 33.2 ± 21 TUNEL-positive cells/high-power field, P < 0.05; Figure 2, A and B ▶ ). In control liver specimens from mice treated with TNF-α after injection with saline or from catB−/− mice infected with Ad5ΔE1, none or rare TUNEL-positive cells were observed. However, apoptosis was increased in catB+/+ livers infected with Ad5ΔE1, possibly because of the partial inhibition of NF-κB observed using this viral construct (Figure 1 ▶ and Figure 2B ▶ ). Thus, TNF-α-mediated hepatocyte apoptosis is attenuated in catB−/− mice compared to catB+/+ mice.

Figure 2.

CatB−/− mice are more resistant to TNF-α-mediated hepatocyte apoptosis. Apoptosis was measured in situ by TUNEL assay in catB+/+and catB−/− mouse livers after a 2-hour treatment with TNF-α. TUNEL-positive cells were visualized by fluorescence microscopy using excitation and emission wavelengths of 490 and 520 nm, respectively. Representative fluorescence photomicrographs of low-power fields of liver of catB+/+ and catB−/− mice injected with Ad5IκB are shown (A) along with quantitation of apoptotic cells per high-power field in controls (saline, Ad5ΔE1) and Ad5IκB-injected animals (B). Original magnifications, ×40. C: Expression of TNF-R1 in catB+/+ and catB−/− mouse livers was evaluated by immunoblot. Aliquots of 60 μg of protein from whole-cell lysates were prepared as described in Materials and Methods and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on a 10% acrylamide gel, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and blotted for TNF-R1. TNF-R1 was detected in both catB+/+ and catB−/− mouse livers after 2 to 4 hours of treatment with TNF-α. The blot for β-actin served as a control for protein loading.

To exclude the possibility that the increased resistance to TNF-α-mediated apoptosis observed in the catB−/− livers is because of reduced expression of TNF-R1, we performed immunoblot analysis for TNF-R1 on whole-cell lysates from livers of catB+/+ and catB−/−. The protein level of TNF-R1 after 2 to 4 hours of treatment with TNF-α was actually increased in catB−/− as compared to catB+/+, demonstrating that TNF-R1 expression is not impaired in catB−/− mice (Figure 2C) ▶ . Thus catB−/− mice increased resistance to TNF-α-mediated hepatocyte apoptosis is independent on the expression of TNF-R1.

Does Cat B Deficiency Prevent Activation of the TNF-α-Triggered Mitochondrial Pathway of Apoptosis?

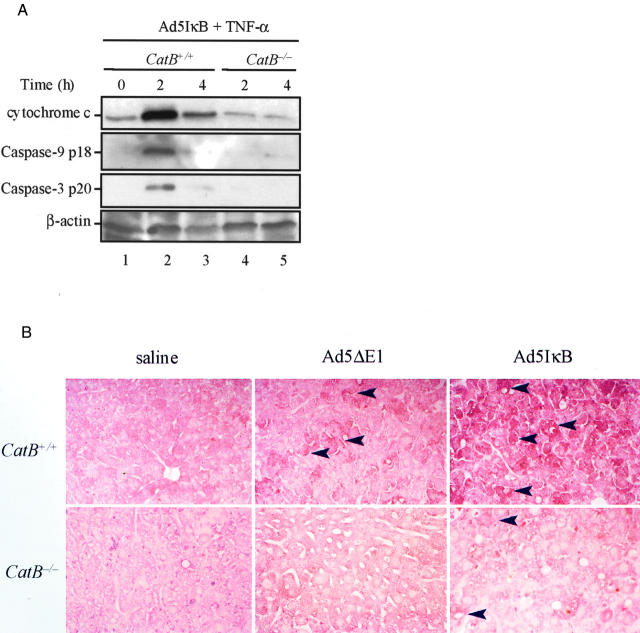

The TNF-α-induced pathway of apoptosis in hepatocytes in vitro is mediated by mitochondrial dysfunction. 11,16 To address the question as to whether the same pathway is also activated in vivo by a cat B-dependent mechanism, we next examined if a change in the intracellular distribution of mitochondrial cytochrome c occurred in Ad5IκB-infected catB+/+ and catB−/− liver cells after TNF-α treatment. Immunoblot analysis of subcellular fractions indicated a significant release of cytochrome c into the cytosol in catB+/+ mouse livers, peaking at 2 hours and significantly decreasing thereafter, possibly because of protein degradation (Figure 3A ▶ , lanes 2 and 3). To further ascertain if cytochrome c release was associated with activation of the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis, we performed immunoblot analysis for active caspases 9 and 3. Consistently, pro-caspase 9 and pro-caspase 3 were also converted into their 18-kd and the 20-kd active subunits, respectively, indicating that caspase activation was associated with the mitochondrial release of cytochrome c (Figure 3A ▶ , lanes 2 and 3). In contrast, cytochrome c and active caspase 9 and caspase 3 subunits were virtually undetectable in the cytosol of catB−/− livers after TNF-α treatment (Figure 3A ▶ , lanes 4 and 5), as well as in cytosol isolated from untreated catB+/+ mice (Figure 3A ▶ , lane 1). Activation of effector caspases 3 and 7 in liver tissue was also assessed by immunohistochemistry using an antibody that specifically recognizes a shared epitope of active caspase 3 and 7 (Figure 3B) ▶ . Liver of mice injected with saline displayed no immunoreactivity for active caspase 3/7 after treatment with TNF-α, whereas a weak reaction was found in specimens from mice injected with Ad5ΔE1, possibly because of a slight toxicity of the virus itself. On the contrary, strongly positive immunoreactivity for active caspase 3/7 was detected in the cytosol of hepatocytes from 2-hour-treated catB+/+ mice injected with Ad5IκB, but not in catB−/− mice. Taken together, these data suggest that cat B is required for triggering the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis in vivo after TNF-α stimulation.

Figure 3.

The mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis is activated in catB+/+ but not in catB−/− mice. CatB+/+ and catB−/− mice were injected with the adenovirus Ad5IκB. Twenty-four hours later, mice were treated intravenously with TNF-α and sacrificed after 2 and 4 hours. A: At the indicated time points, cytosolic fractions were prepared as described in Materials and Methods and aliquots of 60 μg of protein were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on a 15% acrylamide gel, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and sequentially blotted for cytochrome c, active caspase 9, and active caspase 3. Cytosolic cytochrome c and active caspase 9 and 3 were only detected in catB+/+-treated livers. Blot for β-actin served as a control for protein loading. B: Representative immunohistochemistry for active caspase 3 and 7 in catB+/+ and cat B−/− mice injected with saline, Ad5ΔE1 (controls), or Ad5IκB, after a 2-hour treatment with TNF-α. Strongly positive immunochemical staining reaction for active caspase 3 and 7 was detectable in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes from Ad5IκB-injected catB+/+ mice after treatment with TNF-α, but not from catB−/− mice or in controls. The tissue sections were counterstained with eosin. Original magnifications, ×25.

Are CatB−/− Mice Resistant to TNF-α-Induced Liver Injury?

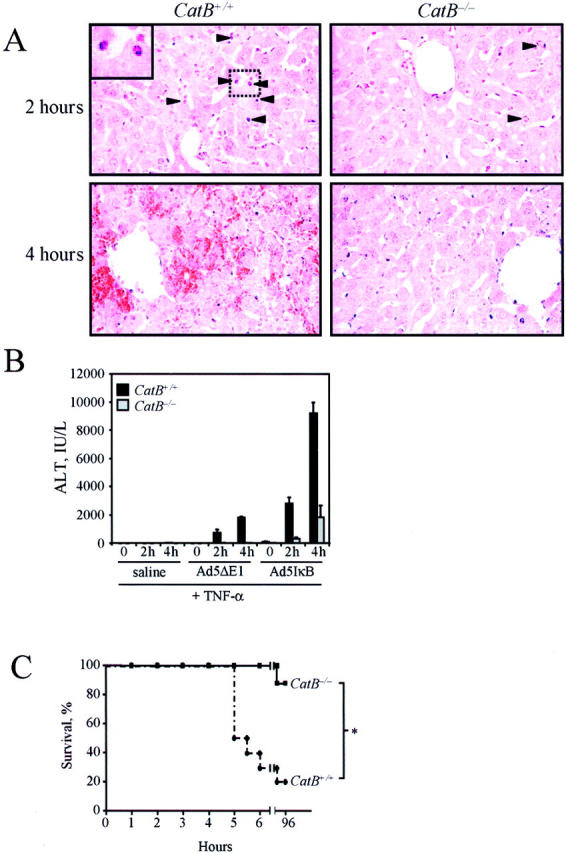

To verify whether cat B-mediated hepatocyte apoptosis plays a role in the progression of TNF-α-induced liver damage, we next examined whether catB−/− mice are also less sensitive to TNF-α-mediated liver injury. TNF-α-treatment resulted in extensive liver damage in catB+/+ mice as demonstrated by histological examination (Figure 4A) ▶ . The liver of these animals after 2 hours of treatment showed a large number of cells with eosinophilic shrunken cytoplasm and dark-colored condensed or fragmented nuclei indicating the occurrence of massive hepatocyte apoptosis. By 4 hours after TNF-α administration, extensive hemorrhagic lesions became evident in association with alterations in liver architecture. In contrast, livers of catB−/− mice showed moderate liver injury and only isolated apoptotic cells were identified after TNF-α treatment (Figure 4A) ▶ . Consistently, serum ALT values, an index of hepatocellular damage, were also significantly lower in catB−/− mice as compared to catB+/+ (311 ± 104 versus 2818 ± 461 U/L at 2 hours, and 1842 ± 823 versus 9215 ± 779 at 4 hours; P < 0.01 catB−/− versus catB+/+; Figure 4B ▶ ). Control mice injected either with Ad5ΔE1 or saline had moderate or no significant liver injury after TNF-α treatment, confirming that NF-κB inhibition is required for TNF-α toxicity (Figure 4B ▶ and data not shown). However, the most remarkable evidence came from the animal survival monitored throughout the 4 days after TNF-α-treatment. CatB−/− mice showed a survival rate of 87.5% (7 of 8) at 96 hours, whereas the vast majority of catB+/+ mice died within 6 hours as a consequence of acute liver failure and only 20% (2 of 10) were still alive at 96 hours (Figure 4C) ▶ . Collectively, these data demonstrate that catB−/− mice are more resistant to TNF-α-induced liver damage.

Figure 4.

. TNF-α induces acute liver damage in catB+/+, but not in catB−/− mice. CatB+/+ and catB−/− mice were injected with the adenovirus Ad5IκB, treated intravenously 24 hours later with TNF-α and sacrificed after 2 and 4 hours. A: Representative microscopic photographs of the liver of catB+/+ and catB−/− mice after 2 and 4 hours of treatment with TNF-α are shown. CatB+/+ mice showed massive hepatocyte apoptosis at 2 hours and extensive hemorrhagic necrosis at 4 hours. Normal liver architecture and few apoptotic hepatocytes were observed in catB−/− mice both at 2 and 4 hours. Arrowheads point to apoptotic cells. Higher magnification of apoptotic cells is shown in the inset. Original magnification, ×40 (H&E). B: Measurement of serum ALT values in catB+/+ and catB−/− mice injected with saline, Ad5ΔE1 (controls), or Ad5IκB, and treated with TNF-α. Serum ALT values were significantly greater in catB+/+ than in catB−/− mice after 2 and 4 hours of treatment with TNF-α. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 6, *P < 0.01 catB+/+ versus catB−/− mice. C: Survival curves of catB+/+ (dotted line) and catB−/− (solid line) mice injected with Ad5IκB and treated with TNF-α (n = 10 catB+/+ and n = 8 catB−/−; *, P < 0.01).

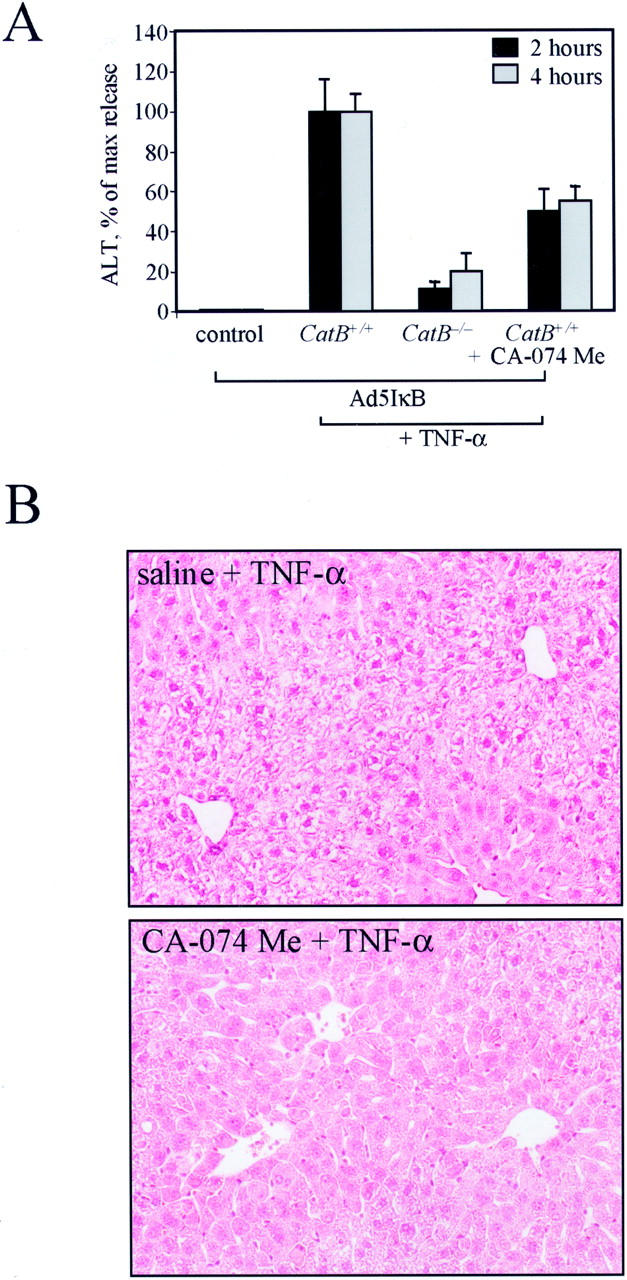

Can TNF-α-Induced Liver Damage Be Prevented by Pharmacological Inhibition of Cat B?

To determine whether pharmacological inhibition of cat B would prove useful in reducing TNF-α-induced liver damage, we pretreated the mice with CA-074 Me, a specific inhibitor of lysosomal cysteine proteases. Thirty minutes before the injection of TNF-α, wild-type mice received an intraperitoneal injection of saline without (controls) or with CA-074 Me, in a concentration proved effective in inhibiting liver cat B activity by 93 to 95% (4 mg/100g; data not shown). Mice were then killed 2 and 4 hours after the injection of TNF-α. Serum ALT levels after TNF-α-treatment were significantly reduced in catB+/+ mice pretreated with CA-074 Me compared to saline-injected controls (Figure 5A) ▶ . Histological examination of liver samples confirmed the presence of extensive hygropic degeneration and architectural distortion predominantly in zone 1-2 in catB+/+ mice. In contrast, liver architecture was preserved and only moderate damage was observed in catB+/+ mice pretreated with CA-074 Me (Figure 5C) ▶ . These findings suggest that pharmacological inhibition of cat B may partially attenuate TNF-α-induced liver damage.

Figure 5.

Pharmacological inhibition of cat B reduces TNF-α-induced liver damage in catB+/+ mice. CatB+/+ mice were injected with the adenovirus Ad5IκB. Twenty-four hours later, mice were given an intraperitoneal injection of 0.9 ml of saline with or without CA-074 Me (4 mg/100 g) 30 minutes before the intravenous injection of TNF-α (0.5 μg), and sacrificed after 2 and 4 hours. A: Serum ALT values after 2 and 4 hours of treatment with TNF-α were significantly reduced in catB+/+ mice pretreated with CA-074 Me (CatB+/+ + CA-074 Me) as compared to catB+/+ mice pretreated with saline (CatB+/+). Measurement of serum ALT values in catB−/− mice (CatB−/−) and untreated catB +/+ mice (control) are also shown. Data are expressed as percentage of release (max release) obtained treating wild-type mice with TNF-α (mean ± SEM). B: Representative photomicrographs of livers of catB+/+ mice pretreated with saline (saline + TNF-α) or with CA-074 Me (CA-074 + TNF-α) and subsequently treated with TNF-α for 2 hours are shown. CatB+/+ mice pretreated with saline showed massive hygropic degeneration and architectural distortion. Liver architecture is preserved and minimal damage is observed in catB+/+ mice pretreated with CA-074 Me. Original magnification, ×40 (H&E).

Discussion

The results of our study relate to the mechanisms of TNF-α-induced hepatocyte apoptosis and liver injury in vivo. Our data demonstrate that deletion of the cat B gene in mice reduces TNF-α-associated hepatocyte apopto- sis, by inhibiting mitochondrial release of cytochrome c and caspase 9 and 3 activation, and TNF-α liver damage and animal mortality. Furthermore, pharmacological inhibition of cat B also partially attenuates TNF-α-induced liver damage in wild-type mice. These data indicate that cat B contributes to an apoptotic cascade upstream of mitochondria in TNF-α-mediated hepatocyte apoptosis, and plays a critical role in the progression of the TNF-α-induced liver damage. These findings have implications for the pharmacological therapy of liver injury by TNF-α, namely the potential use of cat B inhibitors.

Increasing evidence implicates cat B as an apoptotic protease in cell culture and cell-free systems. For example, cat B contributes to bile salt-induced hepatocyte apoptosis, 27,28 and pharmacological inhibition of cat B blocks apoptosis induced by p53 and cytotoxic agents. 29 In several human and murine tumor cell lines, cat B has been described to be a key protease in death receptor-triggered apoptosis, along with or independent of caspases. 17 In a cell-free system, cat B has been shown to cause chromatin condensation, a morphological feature of apoptosis. 30 However, the present findings signify for the first time a role for this protease in vivo during apoptosis. Cat B would seem to contribute to apoptosis by causing mitochondrial dysfunction. Indeed, cytochrome c release and caspase 9 and 3 activation (key events in the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis) were absent in the cat B-null animals treated with TNF-α. How cat B contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction remains to be elucidated, but our previous study in vitro showed that it does require a cytosolic factor(s). 16 A potential cytosolic target for cat B is Bid, a proapoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family of proteins, which is cleaved and activated by caspase 8 during Fas- and TNF-α-mediated apoptosis and is able to induce release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria. 31,32 Bid has also been shown to be proteolytically activated by lysosomal proteases at Arg65, 33 and cat B endoprotease activity does recognize basic amino acids. 34 Identifying the cytosolic target(s) for cat B in apoptosis will provide further mechanistic insight into the pathways by which TNF-α-mediated apoptosis occurs.

Because cat B is a lysosomal protease, our data suggest that TNF-α-induced apoptosis involves lysosomes. Indeed, a previous study has suggested that alkalization of acidic vesicles such as lysosomes attenuates TNF-α-induced apoptosis in vitro. 15 Loss of lysosomal integrity has also been implicated in apoptosis during oxidative stress, 35,36 α-tocopheryl-mediated apoptosis in Jurkat T cells, 37 and 6-hydroxydopamine associated death of cultured microglia. 38 Our current data extends these observations by implicating the existence of a lysosomal pathway for apoptosis in vivo. This lysosomal pathway of apoptosis warrants further attention in liver and other tissues as a key mechanism contributing to apoptosis-related tissue injury.

The findings in this study suggest cat B contributes to liver injury by promoting hepatocyte apoptosis. However, cathepsin has been shown to activate the proinflammatory caspases 1 and 11, 30,39 which contribute to tissue inflammation by activating proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1. 40,41 Thus, cat B gene deletion may not only attenuate TNF-α-mediated hepatocyte apoptosis, but also reduce the inflammatory response elicited by this cytokine. Further studies using additional models of liver injury will not only provide a more complete picture of the role of cat B in apoptosis, but also evaluate this protease as a potential therapeutic target for reducing inflammation-induced hepatocellular damage.

The present demonstration that TNF-α-induced liver injury and death are diminished in catB−/− mice suggests the potential importance of the cat B-mediated pathway. CatB−/− mice develop normally and have no overtly manifest phenotype, indicating that inhibition of cat B itself should not be detrimental. Therefore, based on the present findings, the development of cat B inhibitors for the treatment of liver injury would seem to have merit.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Deussing and C. Peters for providing the catB−/− mice; D. Brenner for providing the adenovirus constructs; A. Srinivasan and S. Kaufmann for providing immunological reagents; L. Burgart, H. Higuchi, and M. Taniai for providing technical assistance; and Sara Erickson for excellent secretarial assistance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Gregory J. Gores, M.D., Professor of Medicine, Mayo Medical School, Clinic, and Foundation, 200 First St. SW, Rochester, MN 55905. E-mail: gores.gregory@mayo.edu.

Supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (DK 41876 to G. J. G.) and the Mayo Foundation, Rochester, Minnesota. M.E.G. is the recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship from the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Italy.

References

- 1.Wallach D, Varfolomeev EE, Malinin NL, Goltsev YV, Kovalenko AV, Boldin MP: Tumor necrosis factor receptor and Fas signaling mechanisms. Annu Rev Immunol 1999, 17:331-367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradham CA, Plumpe J, Manns MP, Brenner DA, Trautwein C: Mechanisms of hepatic toxicity. I. TNF-induced liver injury. Am J Physiol 1998, 275:G387-G392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McClain CJ, Cohen DA: Increased tumor necrosis factor production by monocytes in alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology 1989, 9:349-351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colletti LM, Remick DG, Burtch GD, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM, Campbell DA, Jr: Role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the pathophysiologic alterations after hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury in the rat. J Clin Invest 1990, 85:1936-1943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzalez-Amaro R, Garcia-Monzon C, Garcia-Buey L, Moreno-Otero R, Alonso JL, Yague E, Pivel JP, Lopez-Cabrera M, Fernandez-Ruiz E, Sanchez-Madrid F: Induction of tumor necrosis factor alpha production by human hepatocytes in chronic viral hepatitis. J Exp Med 1994, 179:841-848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leist M, Gantner F, Naumann H, Bluethmann H, Vogt K, Brigelius-Flohe R, Nicotera P, Volk HD, Wendel A: Tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptosis during the poisoning of mice with hepatotoxins. Gastroenterology 1997, 112:923-934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsu H, Xiong J, Goeddel DV: The TNF receptor 1-associated protein TRADD signals cell death and NF-kappa B activation. Cell 1995, 81:495-504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leist M, Gantner F, Kunstle G, Wendel A: Cytokine-mediated hepatic apoptosis. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 1998, 133:109-155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colell A, Garcia-Ruiz C, Miranda M, Ardite E, Mari M, Morales A, Corrales F, Kaplowitz N, Fernandez-Checa JC: Selective glutathione depletion of mitochondria by ethanol sensitizes hepatocytes to tumor necrosis factor. Gastroenterology 1998, 115:1541-1551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boldin MP, Goncharov TM, Goltsev YV, Wallach D: Involvement of MACH, a novel MORT1/FADD-interacting protease, in Fas/APO-1- and TNF receptor-induced cell death. Cell 1996, 85:803-815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradham CA, Qian T, Streetz K, Trautwein C, Brenner DA, Lemasters JJ: The mitochondrial permeability transition is required for tumor necrosis factor alpha-mediated apoptosis and cytochrome c release. Mol Cell Biol 1998, 18:6353-6364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hannun YA: Functions of ceramide in coordinating cellular responses to stress. Science 1996, 274:1855-1859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Earnshaw WC, Martins LM, Kaufmann SH: Mammalian caspases: structure, activation, substrates, and functions during apoptosis. Annu Rev Biochem 1999, 68:383-424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicholson DW: Caspase structure, proteolytic substrates, and function during apoptotic cell death. Cell Death Differ 1999, 6:1028-1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monney L, Olivier R, Otter I, Jansen B, Poirier GG, Borner C: Role of an acidic compartment in tumor-necrosis-factor-alpha-induced production of ceramide, activation of caspase-3 and apoptosis. Eur J Biochem 1998, 251:295-303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guicciardi ME, Deussing J, Miyoshi H, Bronk SF, Svingen PA, Peters C, Kaufmann SH, Gores GJ: Cathepsin B contributes to TNF-alpha-mediated hepatocyte apoptosis by promoting mitochondrial release of cytochrome c. J Clin Invest 2000, 106:1127-1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foghsgaard L, Wissing D, Mauch D, Lademann U, Bastholm L, Boes M, Elling F, Leist M, Jäättelä M: Cathepsin B acts as a dominant execution protease in tumor cell apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor. J Cell Biol 2001, 153:999-1009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iimuro Y, Nishiura T, Hellerbrand C, Behrns KE, Schoonhoven R, Grisham JW, Brenner DA: NFkappaB prevents apoptosis and liver dysfunction during liver regeneration. J Clin Invest 1998, 101:802-811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Antwerp DJ, Martin SJ, Kafri T, Green DR, Verma IM: Suppression of TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis by NF-kappaB. Science 1996, 274:787-789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halangk W, Lerch MM, Brandt-Nedelev B, Roth W, Ruthenbuerger M, Reinheckel T, Domschke W, Lippert H, Peters C, Deussing J: Role of cathepsin B in intracellular trypsinogen activation and the onset of acute pancreatitis. J Clin Invest 2000, 106:773-781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rust C, Karnitz LM, Paya CV, Moscat J, Simari RD, Gores GJ: The bile acid taurochenodeoxycholate activates a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent survival signaling cascade. J Biol Chem 2000, 275:20210-20216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyoshi H, Rust C, Roberts PJ, Burgart LJ, Gores GJ: Hepatocyte apoptosis after bile duct ligation in the mouse involves Fas. Gastroenterology 1999, 117:669-677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyoshi H, Rust C, Guicciardi ME, Gores GJ: NF-kB is activated in cholestasis and function to reduce liver injury. Am J Pathol 2001, 158:967-975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Srinivasan A, Roth KA, Sayers RO, Shindler KS, Wong AM, Fritz LC, Tomaselli KJ: In situ immunodetection of activated caspase-3 in apoptotic neurons in the developing nervous system. Cell Death Differ 1998, 5:1004-1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang J, Liu X, Bhalla K, Kim CN, Ibrado AM, Cai J, Peng TI, Jones DP, Wang X: Prevention of apoptosis by Bcl-2: release of cytochrome c from mitochondria blocked. Science 1997, 275:1129-1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mesner PWJ, Bible KC, Martins LM, Kottke TJ, Srinivasula SM, Svingen PA, Chilcote TJ, Basi GS, Tung JS, Krajewski S, Reed JC, Alnemri ES, Earnshaw WC, Kaufmann SH: Characterization of caspase processing and activation in HL-60 cell cytosol under cell-free conditions. J Biol Chem 1999, 274:22635-22645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts LR, Kurosawa H, Bronk SF, Fesmier PJ, Agellon LB, Leung WY, Mao F, Gores GJ: Cathepsin B contributes to bile salt-induced apoptosis of rat hepatocytes. Gastroenterology 1997, 113:1714-1726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones B, Roberts PJ, Faubion WA, Kominami E, Gores GJ: Cystatin A expression reduces bile salt-induced apoptosis in a rat hepatoma cell line. Am J Physiol 1998, 275:G723-G730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lotem J, Sachs L: Differential suppression by protease inhibitors and cytokines of apoptosis induced by wild-type p53 and cytotoxic agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996, 93:12507-12512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vancompernolle K, Van Herreweghe F, Pynaert G, Van de Craen M, De Vos K, Totty N, Sterling A, Fiers W, Vandenabeele P, Grooten J: Atractyloside-induced release of cathepsin B, a protease with caspase-processing activity. FEBS Lett 1998, 438:150-158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo X, Budihardjo I, Zou H, Slaughter C, Wang X: Bid, a Bcl2 interacting protein, mediates cytochrome c release from mitochondria in response to activation of cell surface death receptors. Cell 1998, 94:481-490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li H, Zhu H, Xu CJ, Yuan J: Cleavage of BID by caspase 8 mediates the mitochondrial damage in the Fas pathway of apoptosis. Cell 1998, 94:491-501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stoka VV, Turk B, Schendel SL, Kim TH, Cirman T, Snipas SJ, Ellerby LM, Bredesen D, Freeze H, Abrahamson M, Bromme D, Krajewski S, Reed JC, Yin XM, Turk VV, Salvesen GS: Lysosomal protease pathways to apoptosis: cleavage of bid, not Pro-caspases, is the most likely route. J Biol Chem 2001, 276:3149-3157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barrett AJ, Kirschke H: Cathepsin B, cathepsin H, and cathepsin L. Methods Enzymol 1981, 80:535-561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nilsson E, Ghassemifar R, Brunk UT: Lysosomal heterogeneity between and within cells with respect to resistance against oxidative stress. Histochem J 1997, 29:857-865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberg K, Johansson U, Ollinger K: Lysosomal release of cathepsin D precedes relocation of cytochrome c and loss of mitochondrial transmembrane potential during apoptosis induced by oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 1999, 27:1228-1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neuzil J, Svensson I, Weber T, Weber C, Brunk UT: Alpha-tocopheryl succinate-induced apoptosis in Jurkat T cells involves caspase-3 activation, and both lysosomal and mitochondrial destabilisation. FEBS Lett 1999, 445:295-300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takai N, Nakanishi H, Tanabe K, Nishioku T, Sugiyama T, Fujiwara M, Yamamoto K: Involvement of caspase-like proteinases in apoptosis of neuronal PC12 cells and primary cultured microglia induced by 6-hydroxydopamine. J Neurosci Res 1998, 54:214-222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schotte P, Van Criekinge W, Van de Craen M, Van Loo G, Desmedt M, Grooten J, Cornelissen M, De Ridder L, Vandekerckhove J, Fiers W, Vandenabeele P, Beyaert R: Cathepsin B-mediated activation of the proinflammatory caspase-11. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1998, 251:379-387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li P, Allen H, Banerjee S, Franklin S, Herzog L, Johnston C, McDowell J, Paskind M, Rodman L, Salfeld J, et al: Mice deficient in IL-1 beta-converting enzyme are defective in production of mature IL-1 beta and resistant to endotoxic shock. Cell 1995, 80:401-411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang S, Miura M, Jung YK, Zhu H, Li E, Yuan J: Murine caspase-11, an ICE-interacting protease, is essential for the activation of ICE. Cell 1998, 92:501-509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]