Abstract

Most large bowel cancers are moderately to well-differentiated adenocarcinomas comprised chiefly or entirely of glands lined by tall columnar cells. We have identified a subset of poorly differentiated colon carcinomas with a distinctive histopathological appearance that we term large cell minimally differentiated carcinomas (LCMDCs). These tumors likely include a group of poorly differentiated carcinomas previously described by others as medullary adenocarcinomas. To better understand the pathogenesis of these uncommon neoplasms, we compared molecular features of 15 LCMDCs to those present in 25 differentiated adenocarcinomas (DACs) of the colon. Tumors were examined for alterations commonly seen in typical colorectal carcinomas, including increased p53 and β-catenin immunoreactivity, K-ras gene mutations, microsatellite instability, and loss of heterozygosity of markers on chromosomes 5q, 17p, and 18q. In addition, tumors were evaluated by immunohistochemistry for CDX2, a homeobox protein whose expression in normal adult tissues is restricted to intestinal and colonic epithelium. Markedly reduced or absent CDX2 expression was noted in 13 of 15 (87%) LCMDCs, whereas only 1 of the 25 (4%) DACs showed reduced CDX2 expression (P < 0.001). Nine of 15 (60%) LCMDCs had the high-frequency microsatellite instability phenotype, but only 2 of 25 (8%) DACs had the high-frequency microsatellite instability phenotype (P = 0.002). Our findings provide support for the hypothesis that the molecular pathogenesis of LCMDCs is distinct from that of most DACs. CDX2 alterations and DNA mismatch repair defects have particularly prominent roles in the development of LCMDCs.

Although the vast majority of colorectal cancers are moderately to well-differentiated adenocarcinomas (DACs) with readily apparent glandular morphology, 1 some carcinomas show minimal or no glandular differentiation. Previous studies suggest these poorly differentiated lesions may be heterogeneous with respect to their clinicopathological and molecular features. 1-5 A recently described subset of poorly differentiated carcinomas, termed “medullary adenocarcinomas,” is characterized by a uniform population of neoplastic cells with chromatin clearing and prominent nucleoli. The tumor cells grow in solid sheets and trabeculae, often associated with a prominent intratumoral and/or peritumoral lymphocytic infiltrate. 1,2 These neoplasms have a propensity to be right-sided and seem to have a relatively favorable prognosis that belies their high-grade histological appearance.

Like other common cancers, colorectal carcinomas are thought to arise through a multistep process in which repeated cycles of somatic mutation of cellular genes and clonal selection of variant progeny with increasingly aggressive growth properties play a prominent role. 6-8 Several of the genetic alterations that contribute to initiation and progression of colorectal tumors have been identified, and they include mutation of specific oncogenes such as K-ras, and tumor suppressor genes, such as p53 and APC. 6-8 Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at loci on chromosomes 5q, 17p, and/or 18q is frequent in colorectal carcinomas. In the case of chromosomes 5q and 17p, LOH is presumed to inactivate the APC and p53 genes, respectively, whereas the gene(s) targeted for inactivation by 18q LOH remain poorly understood. 7,8 A minority of colorectal carcinomas harbor DNA mismatch repair defects and manifest a phenotype in which there is a high frequency of instability at microsatellite sequence tracts. Microsatellite instability (MSI) is observed in essentially all colorectal cancers arising in patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and in ∼10 to 15% of apparently sporadic colorectal cancers 7-9 . Defects in mismatch repair function are thought to increase the rate at which cells acquire the mutations critical in malignant transformation. 7-9

For the most part, previous studies of colorectal carcinoma have not sought to directly address the relationship between specific histopathological features and molecular changes. Nevertheless, there is strong evidence that sporadic colorectal carcinomas with MSI are frequently poorly differentiated, right-sided, and associated with a prominent inflammatory infiltrate. 2,10-16 In one study, MSI was correlated with carcinomas of the medullary subtype. 2

Several studies have implicated alterations in CDX2, a caudal-related homeobox gene encoding a transcription factor, in colorectal tumor development. Mice heterozygous for a germline, inactivating mutation of the Cdx2 gene develop multiple polyps in the small intestine and colon, with most prominent involvement of the proximal colon. 17-19 The morphological features of the polyps in Cdx2+/− mice seem complex, but the lesions have recently been hypothesized to result from a complete loss of Cdx2 expression and function, with consequent reprogramming of intestinal differentiation and regeneration of epithelial cell types normally found in proximal regions of the gastrointestinal tract (eg, stomach and esophagus). 19 Inactivating mutations in the CDX2 gene seem to be very rare in human colorectal cancers, although a reduction of CDX2 transcripts has been seen in some human colorectal cancer cell lines and high-grade colonic dysplasias and invasive carcinomas. 20-23

In preliminary immunohistochemical studies, we noted loss of CDX2 expression more frequently in poorly DACs than in more well differentiated tumors (ER Fearon, E Macri, and M Loda, unpublished data). We sought to further address the potential contribution of CDX2 alterations in colorectal carcinomas and chose to characterize CDX2 expression in a subset of poorly differentiated colonic carcinomas that we term “large cell minimally differentiated carcinomas” (LCMDCs). These tumors likely include lesions of the type previously described as medullary adenocarcinomas. To address the relationship of LCMDCs to more typical adenocarcinomas, we compared the frequency of several molecular alterations in LCMDCs to those present in DACs. In addition to studying CDX2 expression, tumors were evaluated for K-ras mutations; the MSI phenotype; LOH on chromosomes 5q, 17p, and 18q; and altered expression of the β-catenin and p53 proteins.

Materials and Methods

Tumor Specimens

This study was conducted with approval from the University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board. Fifteen LCMDCs and 25 typical DACs accessioned at the University of Michigan between 1988 and 1995 were obtained from the Surgical Pathology archives. The histopathology of each tumor was reviewed by two surgical pathologists (HDA and PCL). All LCMDCs were interpreted as primary colorectal carcinomas based on an in situ component and/or the presence of recognizable, albeit minimal, glandular differentiation in at least a portion of the tumor specimen. In addition, the available clinical record did not indicate the diagnosis of another primary cancer in any of the patients. Five consecutive 5-μm formalin-fixed tissue sections were cut from each paraffin block, mounted on glass slides, then weakly stained with hematoxylin. Specific regions (neoplastic versus non-neoplastic tissue) were carefully microdissected with 22-gauge needles under a light microscope, using adjacent Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections as dissection guides. Genomic DNA was extracted from microdissected neoplastic tissue and matched non-neoplastic tissue using standard methods. 24

CDX2 Antibody

A polyclonal antiserum against the human CDX2 protein was generated by immunizing a rabbit with a purified recombinant fusion protein in which CDX2 amino acids 2 to 194 were fused to glutathione-S-transferase sequences. This region of CDX2 lacks the sequence-specific DNA-binding homeobox domain and shares only limited similarity with other mammalian caudal-related proteins (eg, CDX1). After five booster immunizations, each separated by 3 weeks, CDX2-specific IgG fractions were immunoaffinity purified by incubation with an independent, albeit related, recombinant CDX2 protein immobilized to 4% cross-linked beaded agarose support (AminoLink Plus Immobilization Kit; Pierce, Rockford, IL). This latter recombinant CDX2 fusion protein contained human CDX2 amino acids 2 to 164 fused to a hexahistidine (His6) peptide. The specificity of the affinity-purified anti-CDX2 antibody was tested by Western blot, immunofluorescent, and immunohistochemical studies of human kidney 293 cells engineered to overexpress CDX2 and human colon cancer cell lines known to express variable levels of endogenous CDX2 transcripts. Specificity of the antibody was also assessed by immunohistochemical staining of normal adult colonic mucosa.

Immunohistochemical Staining

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned at 5 μm and deparaffinized in two changes of xylene for 10 minutes each. Sections were hydrated into distilled water through a series of graded alcohols. Antigen enhancement was performed by boiling slides in a microwave oven for 10 minutes in citrate buffer diluted to 1× from 10× Antigen Retrieval Citra Solution (Biogenex, San Ramon, CA). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubation with 6% hydrogen peroxide in methanol. Slides were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then incubated with blocking serum for 10 minutes in a humidified chamber. After additional PBS washes, slides were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody. Affinity-purified, polyclonal rabbit antibody to CDX2 was used at 100-fold dilution; the DO-7 mouse monoclonal antibody against p53 (Novocastra Laboratories Ltd./Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA), was used at 25-fold dilution; and the C19220 mouse monoclonal antibody against β-catenin (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY) was used at a dilution of 1:500. After washing in PBS, slides were incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit or biotinylated goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies for 30 minutes at room temperature. Antigen-antibody complexes were detected with the avidin-biotin-peroxidase method using diaminobenzidine as a chromogenic substrate (Vectastain ABC-Immunostaining Kit; Vector Laboratories, Inc.), as recommended by the manufacturer. Sections were lightly counterstained with hematoxylin, then evaluated by light microscopy. Each tumor section contained normal colonic mucosa as an internal control. A negative control in which primary antibody was omitted was performed with each staining.

K-ras Mutation Analysis

A 162-bp segment of the K-ras gene encompassing codons 1 to 36 was amplified using primers K1a (5′-GGCCTGCTGAAAATGACTGA) and K1b (5′-GTCCTGCACCAGTAATATGC). 25 Genomic DNA templates were suspended in a total volume of 50 μl of reaction buffer containing 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 50 mmol/L KCl, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 200 mmol/L of each primer, 200 μmol/L of each deoxynucleotide triphosphate, and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) conditions were as follows: 60 seconds at 94°C, 60 seconds at 55°C, and 90 seconds at 72°C for 35 cycles, followed by 10 minutes at 72°C. PCR products were electrophoretically separated on 2% agarose gels, purified with QIAquick Gel Extraction kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and directly sequenced by ThermoSequenase-radiolabeled terminator cycle-sequencing (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each result was confirmed by independent PCR and direct sequencing.

MSI Analysis

We used the MSI criteria and primers defined at “The International Workshop on Microsatellite Instability and RER Phenotypes in Cancer Detection and Familial Predisposition.” 26 The initial panel of microsatellite loci studied included two mononucleotide repeats (BAT25 and BAT26) and three dinucleotide repeats (D2S123, D5S346, and D17S250). In a subset of the specimens, analysis was performed with additional markers (BAT40 and D18S55). PCR was performed in 20-μl reaction mixtures containing 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 50 mmol/L KCl, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 200 nmol/L of each primer, 200 μmol/L of each deoxynucleotide triphosphate, 1.5 μCi of[α-32P]dCTP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), and 0.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase. DNA fragments for each microsatellite locus were amplified for 35 cycles of 94°C for 60 seconds, 55°C for 60 seconds, and 72°C for 90 seconds followed by a final extension for 10 minutes at 72°C. PCR products were diluted 10-fold in denaturing buffer containing 95% formamide and 10 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and then denatured at 90°C for 3 minutes. Two μl of denatured sample was electrophoresed on 5% polyacrylamide/6 mol/L urea gels, and visualized by autoradiography. Tumors were classified as follows: high-frequency MSI (MSI-H), when more than one third of the evaluable markers showed instability; MSI-L, when less than one third of evaluable markers showed instability; or microsatellite stable (MSS), when none of the markers showed instability.

LOH Analysis

DNA samples from tumor tissues were analyzed for LOH at specific loci by comparison with DNA from matched normal tissues. The genotype at polymorphic microsatellite sequences was assessed by PCR amplification using the following primer sets: D5S592 (5q22.1), D5S1384 (5q22.2-22.3), TP53 (17p13.1), D17S1303 (17p13.1-13.3), D18S499 (18q21.32-21.33), and D18S814 (18q21.32-21.33). Detailed information on the markers can be obtained from the Genome Data Base (http://gdbwww.gdb.org/). Genomic DNA templates were suspended in a total volume of 20 μl of PCR buffer containing 67 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 16 mmol/L (NH4)2SO4, 0.01% Tween-20, 1.5 or 3.0 mmol/L MgCl2, 200 μmol/L of each deoxynucleotide triphosphate, 1.5 μCi of [α-32P]dCTP, and 0.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase. Target DNA sequences were amplified using an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 2 minutes followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 45 seconds, 55 or 57°C for 45 seconds, and 72°C for 1 minute, with a final extension step at 72°C for 7 minutes. PCR products were resolved by electrophoresis on 5% denaturing polyacrylamide-sequencing gels. LOH was scored when there was a relative decrease (>50%) in the intensity of the signal of one allele in the tumor compared with the allele signal in matched normal DNA. Tumors were scored as uninformative when only one allele was present in DNA from matched normal tissue.

Statistical Analysis

The relationship between molecular features and histological type of carcinoma was tested by Fisher’s exact test. The relationship between survival time and cohort characteristics were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and the resulting curves were compared using the log-rank test. A 5% significance level was used for all tests.

Results

Clinical Features and Histopathology

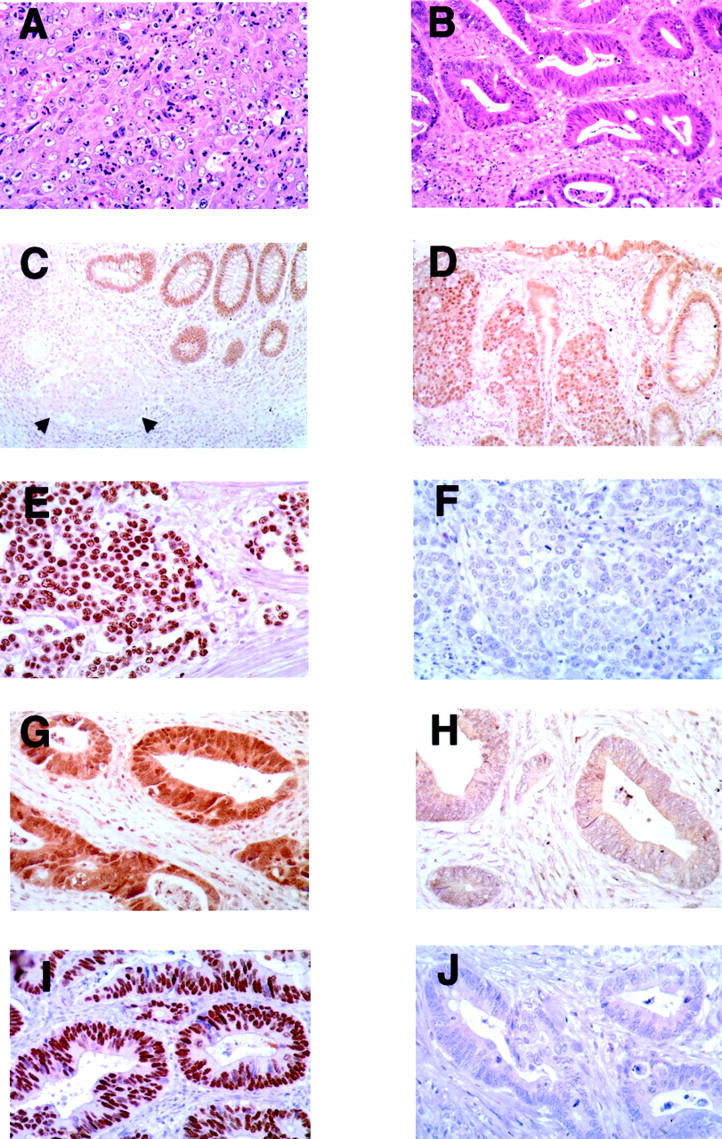

The 15 patients with LCMDCs ranged in age from 30 to 83 years (mean, 64.3 years) (Table 1) ▶ . The 30-year-old patient had a long-standing history of Crohn’s disease. Nine patients were female and six were male. The LCMDCs were predominantly right-sided, with 13 of the 15 arising in the cecum or ascending colon. Histologically, the neoplastic cells in LCMDCs were large, polygonal, and characterized by central chromatin clearing and prominent nucleoli. The cells were arranged in solid sheets, nests, or trabeculae with only rare foci of tubular differentiation (Figure 1A) ▶ . A prominent intratumoral and/or peritumoral lymphocytic infiltrate was often, but not always, present. In contrast, typical DACs showed overt glandular differentiation throughout the tumor, with tubules of varying shapes and sizes lined by tall columnar epithelial cells with variable mucin content (Figure 1B) ▶ .

Table 1.

Immunohistochemical Analysis of CDX2 and p53 Proteins and a Summary of Genetic Alterations in LCMDCs

| Case | Age/gender | Tumor site | Expression* | K-ras mutation | MSI-H | LOH† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDX2 | p53 | 5q | 17p | 18q | |||||

| 1 | 80 F | Right | 0 | 0 | − | + | − | N | + |

| 2 | 55 F | Left | 2+ | 0 | − | + | − | N | N |

| 3 | 64 M | Right | 0 | 0 | − | + | − | + | − |

| 4 | 30 M | Right | 1+ | 3+ | − | − | + | + | + |

| 5 | 76 F | Right | 0 | 3+ | − | − | − | − | − |

| 6 | 71 F | Right | 0 | 1+ | − | + | − | − | + |

| 7 | 72 M | Right | 0 | 2+ | − | + | + | − | + |

| 8 | 83 F | Right | 0 | 0 | − | + | N | N | N |

| 9 | 64 M | Right | 0 | 0 | − | − | + | − | + |

| 10 | 84 F | Right | 0 | 0 | + | + | − | − | − |

| 11 | 42 F | Right | 1+ | 0 | − | + | N | − | − |

| 12 | 68 M | Left | 0 | 3+ | − | − | − | − | − |

| 13 | 56 F | Right | 2+ | 3+ | − | − | N | N | N |

| 14 | 77 F | Right | 0 | 0 | + | + | N | N | N |

| 15 | 43 M | Right | 0 | 3+ | − | − | − | − | − |

*Nuclear staining scored, with “3+” the CDX2 staining seen in normal colonic mucosa and “0” the p53 staining seen in normal colonic mucosa.

†+, LOH; −, retention of heterozygosity; N, noninformative or not evaluated.

Figure 1.

Histological appearance and CDX2 and p53 expression in representative LCMDCs and DACs. A and B: H&E-stained LCMDC and DAC, respectively. C and D: LCMDC stained with anti-CDX2 antibody showing reactivity only in normal epithelium (C; arrows indicate neoplastic cells) and reactivity in both neoplastic cells (2+ scoring) and normal glands (D). E and F: LCMDC stained with anti-p53 antibody showing strong (3+ reactivity) in E and no reactivity in F. G and H: DACs stained with anti-CDX2 antibody showing moderate (2+ scoring) reactivity in G and weak (1+ scoring) staining in H. I and J: DACs stained with anti-p53 antibody with strong (3+ scoring) staining in I and no reactivity in J. Note that cancers often had variable, albeit weak, cytoplasmic staining of CDX2. Hence, only the levels of nuclear CDX2 staining were scored.

MSI, K-ras Mutations, and LOH in LCMDCs

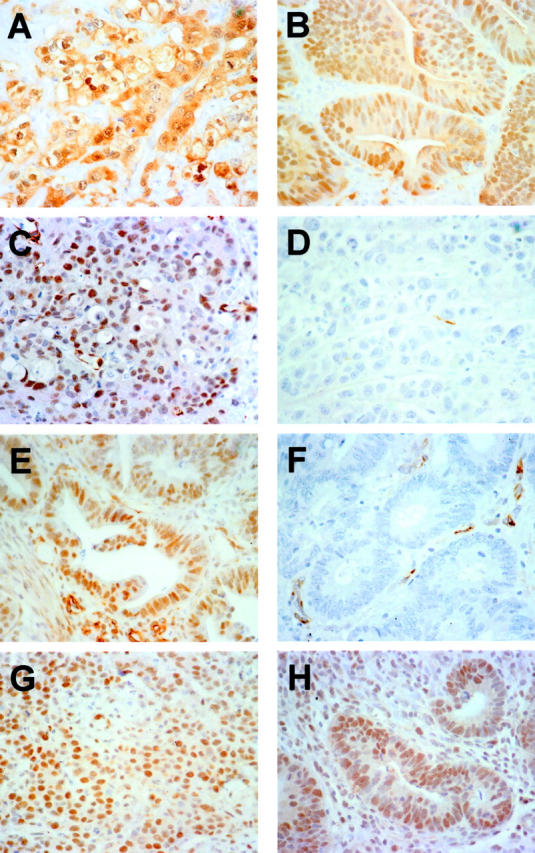

Nine of the 15 (60.0%) LCMDCs had instability at more than two loci and were classified as MSI-H (Tables 1 and 2) ▶ ▶ . The remaining six cases showed no instability at any of the loci examined (MSS). To investigate the basis for the MSI-H phenotype, we performed immunohistochemical studies of the expression of two mismatch repair proteins previously found to be altered in MSI-H cases, namely MLH1 and MSH2. 27-29 Although all six LDMDCs that showed no instability had strong nuclear staining for MLH1 (example in Figure 2C ▶ ), loss of MLH1 expression was seen in all nine LCMDCs with the MSI-H phenotype (example in Figure 2D ▶ ). All 15 LCMDCs showed strong nuclear staining for MSH2 (example in Figure 2G ▶ ). Mutations at K-ras codons 12 and 13 were assessed by sequence analysis and were identified in 2 of 15 tumors (13.3%) (Table 1) ▶ . Both tumors had the same mutation at K-ras codon 13 [GGT (Gly) → GAC (Asp)]. LOH on chromosomes 5q, 17p, and 18q was determined, because LOH of these chromosomes has been frequently seen in primary colorectal carcinomas. LOH on chromosomes 5q, 17p, and 18q was identified in 3 of 11 (27.3%), 2 of 10 (20.0%), and 5 of 11 (45.5%) informative tumors, respectively (Tables 1 and 3) ▶ ▶ .

Table 2.

Microsatellite Instability and MLH1 and MSH2 Expression Analyses of LCMDCs

| Case | Instability at locus* | Immuno- histochemistry† | Interpretation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAT25 | BAT26 | D5S346 | D2S123 | D17S250 | BAT-40 | D18S55 | MSH2 | MLH1 | ||

| 1 | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | MSI-H |

| 2 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | MSI-H |

| 3 | + | + | − | − | ;*>;0>‡ | + | + | + | − | MSI-H |

| 4 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | MSS |

| 5 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | MSS |

| 6 | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | MSI-H |

| 7 | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | MSI-H |

| 8 | + | + | ;*>;0>‡ | − | + | + | + | + | − | MSI-H |

| 9 | − | − | − | − | − | − | ;*>;0>‡ | + | + | MSS |

| 10 | + | + | − | − | ;*>;0>‡ | + | + | + | − | MSI-H |

| 11 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | MSI-H |

| 12 | − | − | − | − | ;*>;0>‡ | − | ;*>;0>‡ | + | + | MSS |

| 13 | − | − | ;*>;0>‡ | − | − | − | ;*>;0>‡ | + | + | MSS |

| 14 | − | + | − | − | ;*>;0>‡ | + | − | + | − | MSI-H |

| 15 | − | − | − | − | − | ;*>;b>‡ | ;*>;b>‡ | + | + | MSS |

*Instability detected: “+”; not detected: “−”.

†Nuclear staining detected: “+”; not detected: “−”.

‡Indicates not evaluated.

MSI-H, High-frequency microsatellite instability; MSS, microsatellite stable.

Figure 2.

β-catenin, MLH1, and MSH2 staining in representative LCMDCs and DACs. A and B: Staining of LCMDC and DAC cases, respectively, with anti-β-catenin antibody showing strong cytosolic and nuclear staining. C and D: LCMDCs stained with anti-MLH1 antibody showing strong nuclear staining in C (MSS case), but not in D (MSI-H case). E and F: DACs stained with anti-MLH1 antibody with strong nuclear staining in E (MSS case), but not in F (MSI-H case). G and H: Staining of LCMDC and DAC cases, respectively, with anti-MSH2 antibody, with both cases showing strong nuclear reactivity.

Table 3.

Loss of Heterozygosity Analysis of LCMDCs

| Case | Loss of heterozygosity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D5S592 | D5S1384 | TP53 | D17S1303 | D18S499 | D18S814 | |

| 1 | − | − | N | N | − | + |

| 2 | − | − | N | N | N | N |

| 3 | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| 4 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 5 | − | − | − | − | − | N |

| 6 | − | − | − | − | + | N |

| 7 | + | − | − | N | − | + |

| 8 | N | ;*>;0>* | ;*>;0>* | N | ;*>;0>* | ;*>;0>* |

| 9 | ;*>;0>* | + | N | − | + | ;*>;0>* |

| 10 | ;*>;0>* | − | − | N | − | ;*>;0>* |

| 11 | ;*>;0>* | ;*>;0>* | ;*>;0>* | − | − | − |

| 12 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 13 | ;*>;0>* | ;*>;0>* | ;*>;0>* | ;*>;0>* | ;*>;0>* | ;*>;0>* |

| 14 | ;*>;0>* | N | N | N | N | ;*>;0>* |

| 15 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

+, LOH; −, retention of heterozygosity; N, noninformative.

*, Not evaluated.

Expression of CDX2, p53, and β-Catenin in LCMDCs

All 15 LCMDCs were evaluated for CDX2 expression by immunohistochemistry. Consistent with previous findings, 20 we found CDX2 was chiefly localized to the nuclei of normal intestinal epithelial cells. In each tumor section, normal colonic mucosa was present and displayed intense immunoreactivity in epithelial nuclei (score of +3), serving as a useful internal positive control for each specimen. Compared to adjacent normal mucosa, all 15 LCMDCs showed reduced expression of CDX2 (Table 4) ▶ . Eleven tumors (73.3%) lacked any detectable CDX2 reactivity in the nuclei of neoplastic cells (score of 0, Figure 1C ▶ ). Two tumors showed weak CDX2 immunoreactivity in nuclei of neoplastic cells (score of 1+) and two showed moderate reactivity (score of 2+, Figure 1D ▶ ). We also evaluated p53 expression in LCMDCs by immunohistochemistry. Five of 15 LCMDCs (33.3%) revealed intense nuclear staining (score of 3+) for p53 (Figure 1E) ▶ , consistent with the presence of a mutant p53 protein with prolonged half-life (Table 4) ▶ . Eight cases showed no detectable p53 reactivity (score of 0, Figure 1F ▶ ), and one case each showed weak (score of 1+) or moderate (score of 2+) staining. In contrast to the membrane pattern of β-catenin reactivity seen in normal colonic mucosa, all 15 LCMDCs showed markedly increased levels of β-catenin in the cytosol and/or nucleus (Figure 2A) ▶ , consistent with the known consequences of inactivating mutations in the APC or axin genes or activating mutations in β-catenin in colon cancers. 30-34

Table 4.

Comparison of CDX2 and p53 Expression, Microsatellite Instability, and K-ras Mutation in LCMDCs versus DACs of the Colon

| Features | No. of cases (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LCMDC | Well differentiated | ||

| CDX2 expression | |||

| 3+ | 0 (0) | 3 (12.0) | |

| 2+ | 2 (13.3) | 21 (84.0) | <0.001* |

| 1+ | 2 (13.3) | 1 (4.0) | |

| 0 | 11 (73.3) | 0 (0) | |

| p53 expression | |||

| 3+ | 5 (33.3) | 11 (44.0) | |

| 2+ | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 0.740† |

| 1+ | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0) | |

| 0 | 8 (53.3) | 14 (56.0) | |

| MSI | |||

| MSI-H | 9 (60.0) | 2 (8.0) | 0.002 |

| MSS/MSI-L | 6 (40.0) | 23 (92.0) | |

| K-ras gene | |||

| Mutation | 2 (13.3) | 11 (44.0) | 0.080 |

| Wild type | 13 (86.7) | 14 (56.0) | |

*The correlation was analyzed between ≥2+ and ≤1+.

†The correlation was analyzed between 3+ and ≤2+.

Molecular and Clinical Features in LCMDCs versus DACs

Studies analogous to those described above were performed on 25 DACs (Table 4) ▶ . Although nuclear CDX2 expression was markedly reduced or absent (score of 0 or 1+) in 13 of 15 (87%) LCMDCs, reduced CDX2 expression was seen in only 1 of the 25 (4%) DACs. This difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001). Representative DACs showing retention and loss of CDX2 expression are shown in Figure 1, G and H ▶ , respectively. Strong reactivity for p53 (score of 3+) was observed in 11 of 25 (44%) DACs (example in Figure 1I ▶ ), whereas 14 of the 25 (56%) showed no p53 immunoreactivity (Figure 1J) ▶ . The data on p53 immunoreactivity revealed no significant difference between LCMDCs and DACs (P = 0.74). Similarly, as was seen in all 15 LCMDCs, all 25 DACs showed markedly increased cytoplasmic and/or nuclear staining for β-catenin (example in Figure 2B ▶ ), indicating that defects in the Wnt/APC/β-catenin pathway are common to both LCMDCs and DACs. Consistent with data in the literature, 2 (8%) and 11 (44%) DACs had the MSI-H phenotype and K-ras mutations, respectively. 35 Although all DACs showed strong nuclear expression of MSH2 (example in Figure 2H ▶ ), one of the two DACs with the MSI-H phenotype had lost MLH1 expression (Figure 2F) ▶ and the remaining 23 DACs of MSS/MSI-L phenotype all showed strong nuclear expression of MLH1 (Figure 2E) ▶ . The decreased frequency of K-ras mutations in LCMDCs compared to DACs was not statistically significant (P = 0.08; Table 4 ▶ ). However, compared to DACs, LCMDCs were far more frequently characterized by the MSI-H phenotype and loss of MLH1 expression (P = 0.002).

Survival data were available for 24 of the 25 patients with DACs and 14 of the 15 patients with LCMDCs. The average follow-up interval for the surviving patients was ∼5.4 years (range, 1.5 to 10.1 years). For the deceased patients, the average follow-up was 2.2 years (range, 0.1 to 9.2 years). Of the 14 patients with LCMDCs for whom follow-up information was available, 8 had died at the time of follow-up (seven with disease, one without disease). Of the 24 patients with DACs for whom survival data were available, 14 had died at the time of follow-up (nine with disease, five without disease). Kaplan-Meier survival estimates showed the difference between the survival of patients with LCMDCs and DACs was not statistically significant (P = 0.345, log-rank test). Kaplan-Meier survival estimates also indicated that there were no statistically significant relationships observed between survival and CDX2 expression, p53 expression, K-ras mutation, or MSI (data not shown).

Discussion

Considerable progress has been made in defining critical mutations and gene expression changes in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Several of the genetic alterations identified thus far are frequently seen in the most common type of malignant colorectal tumors, ie, the overtly glandular, moderately to well-differentiated adenocarcinomas. Relatively few studies have sought to directly explore the notion that colonic carcinomas might include subgroups of tumors characterized by particular histopathological and molecular genetic features. As noted above, a subset (estimates ranging from 10 to 25%) of sporadic colorectal cancers manifest the MSI-H phenotype as a result of defects in DNA mismatch repair. 8,15,36-38 The MSI-H phenotype in colorectal carcinoma has been correlated with right-sided lesions, poor differentiation, and the presence of a prominent inflammatory infiltrate. 2,10-16

In the studies presented here, we chose to analyze the molecular features of a group of poorly differentiated colorectal cancers with a distinct histopathological appearance that we term LCMDCs. Nearly all LCMDCs showed loss of CDX2 protein. In addition, when compared to typical DACs, LCMDCs far more frequently manifested the MSI-H phenotype. The frequent loss of CDX2 protein in LCMDCs does not seem to be simply a reflection of poor differentiation, because substantial levels of CDX2 expression were observed in two LCMDCs and CDX2 expression was often observed in other types of poorly differentiated colorectal carcinomas, such as small-cell undifferentiated carcinomas and poorly differentiated carcinomas with sarcomatoid or squamoid features (Fearon laboratory, unpublished observations).

Whether the lesions that we term LCMDCs are analogous to the colorectal cancers that have been termed by others as “medullary adenocarcinomas” is unclear at this point. To date, only a total of 24 colorectal medullary adenocarcinomas appear to have been described in the literature in any detail. Jessurun and colleagues 1,39 were the first to report on this entity. They describe medullary adenocarcinomas as comprised of small intermediate-sized, round to polygonal uniform cells with scant eosinophilic or amphophilic cytoplasm, rounded nuclei, chromatin clearing, and small central nucleoli. Most, but not all of the tumors characterized by Jessurun and colleagues 1,39 were accompanied by a prominent intratumoral and peritumoral inflammatory response. Tumors were recognized as medullary if at least 80% of the neoplastic cells exhibited a solid, nested, organoid, or trabecular growth pattern. Jessurun and colleagues 1,39 also noted a striking predominance of the neoplasm in women (11 of 11), location in the cecum or ascending colon, and relatively favorable prognosis. Rüschoff and co-workers 2 have reported 13 additional medullary adenocarcinomas. They compared poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas of the medullary type (with uniform cells) to another group of poorly differentiated colorectal cancers, albeit tumors that had a high degree of cellular pleomorphism. Although the medullary adenocarcinomas in the Rüschoff series also showed a predilection for involvement of the cecum or ascending colon, this was not uniform, as one lesion arose in the transverse colon, and another in the rectum. Moreover, 6 of the 13 lesions arose in men. All 13 lesions lacked strong p53 immunoreactivity (presumably indicating wild-type p53 protein) and the tumors uniformly exhibited MSI. Comparison of the Rushoff and colleagues 2 findings on medullary adenocarcinomas to the LCMDCs in our study indicates both similarities and differences. Similar to the Rüschoff and colleagues 2 findings on medullary adenocarcinomas, the clinicopathological features of our LCMDCs were not entirely homogeneous, although we observed that LCMDCs were usually right-sided and more often affected women. Molecular features of LCMDCs were overlapping with but distinct from those seen in the medullary adenocarcinomas of Rüschoff and colleagues. 2 Specifically, we found LCMDCs commonly but not invariably had the MSI phenotype, and stabilization of p53 protein was observed in a third of our cases.

In our study, the survival of patients with LCMDCs was not significantly different from that of patients with DACs, perhaps reflecting the relatively small number of patients of each type studied. However, because patients with medullary adenocarcinomas have been suggested to have a more favorable prognosis than patients with other poorly differentiated colorectal adenocarcinomas, 2,4 it is possible that LCMDCs may constitute a somewhat more clinically and biologically heterogeneous group than medullary adenocarcinomas. Consistent with this proposal, as noted above, MSI was seen in 60% of our LCMDCs, whereas Rüschoff and colleagues 2 report MSI to be a uniform feature of their medullary adenocarcinomas. Nevertheless, the observation that CDX2 expression was lost in nearly all LCMDCs implies that certain molecular changes may be characteristic of the pathogenesis of this subgroup. Evaluation of CDX2 expression in the tumors previously described as medullary adenocarcinomas might shed additional light on the relationship between medullary adenocarcinomas and LCMDCs. Moreover, clarification of the mechanisms underlying loss of CDX2 expression should improve understanding of the pathogenesis of colorectal tumors, especially LCMDCs.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Eric R. Fearon or Kathleen R. Cho, Division of Medical Genetics, Department of Internal Medicine, 4301 MSRB III, 150 W. Medical Center Drive, Ann Arbor, MI 48109. E-mail: fearon@umich.edu or kathcho@umich.edu.

Supported by National Institutes of Health (grant RO1CA82223) and in part by the Naito Foundation (Japan) (to T. H.).

T. H. and M. T. contributed equally to this study.

References

- 1.Jessurun J, Romero-Guadarrama M, Manivel JC: Medullary adenocarcinoma of the colon: clinicopathologic study of 11 cases. Hum Pathol 1999, 30:843-848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruschoff J, Dietmaier W, Luttges J, Seitz G, Bocker T, Zirngibl H, Schlegel J, Schackert HK, Jauch KW, Hofstaedter F: Poorly differentiated colonic adenocarcinoma, medullary type: clinical, phenotypic, and molecular characteristics. Am J Pathol 1997, 150:1815-1825 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reyes CV, Siddiqui MT: Anaplastic carcinoma of the colon: clinicopathologic study of eight cases of a poorly recognized lesion. Ann Diag Pathol 1997, 1:19-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugao Y, Yao T, Kubo C, Tsuneyoshi M: Improved prognosis of solid-type poorly differentiated colorectal adenocarcinoma: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study. Histopathology 1997, 31:123-133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawabata Y, Tomita N, Monden T, Ohue M, Ohnishi T, Sasaki M, Sekimoto M, Sakita I, Tamaki Y, Takahashi J, Yagyu T, Mishima H, Kikkawa N, Monden M: Molecular characteristics of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and signet-ring-cell carcinoma of colorectum. Int J Cancer 1999, 84:33-38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B: A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell 1990, 61:759-767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fearon ER: Molecular biology of gastrointestinal cancers. ed 6 DeVita VT, Jr Hellman S Rosenberg SA eds. Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology, 2001, :pp 1037-1051 Lippincott, William, and Wilkins Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B: Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell 1996, 87:159-170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marra G, Boland CR: Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer: the syndrome, the genes, and historical perspectives. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995, 87:1114-1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lothe RA, Peltomaki P, Meling GI, Aaltonen LA, Nystrom-Lahti M, Pylkkanen L, Heimdal K, Andersen TI, Moller P, Rognum TO, Fossa SD, Haldorsen T, Langmark F, Brogger A, de la Chappelle A, Borrensen AL: Genomic instability in colorectal cancer: relationship to clinicopathological variables and family history. Cancer Res 1993, 53:5849-5852 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Risio M, Reato G, di Celle PF, Fizzotti M, Rossini FP, Foa R: Microsatellite instability is associated with the histological features of the tumor in nonfamilial colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 1996, 56:5470-5474 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dolcetti R, Viel A, Doglioni C, Russo A, Guidoboni M, Capozzi E, Vecchiato N, Macri E, Fornasarig M, Boiocchi M: High prevalence of activated intraepithelial cytotoxic T lymphocytes and increased neoplastic cell apoptosis in colorectal carcinomas with microsatellite instability. Am J Pathol 1999, 154:1805-1813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forster S, Sattler HP, Hack M, Romanakis K, Rohde V, Seitz G, Wullich B: Microsatellite instability in sporadic carcinomas of the proximal colon: association with diploid DNA content, negative protein expression of p53, and distinct histomorphologic features. Surgery 1998, 123:13-18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chao A, Gilliland F, Willman C, Joste N, Chen IM, Stone N, Ruschulte J, Viswanatha D, Duncan P, Ming R, Hoffman R, Foucar E, Key C: Patient and tumor characteristics of colon cancers with microsatellite instability: a population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2000, 9:539-544 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim H, Jen J, Vogelstein B, Hamilton SR: Clinical and pathological characteristics of sporadic colorectal carcinomas with DNA replication errors in microsatellite sequences. Am J Pathol 1994, 145:148-156 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexander J, Watanabe T, Wu TT, Rashid A, Li S, Hamilton SR: Histopathological identification of colon cancer with microsatellite instability. Am J Pathol 2001, 158:527-535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tamai Y, Nakajima R, Ishikawa T, Takaku K, Seldin MF, Taketo MM: Colonic hamartoma development by anomalous duplication in Cdx2 knockout mice. Cancer Res 1999, 59:2965-2970 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chawengsaksophak K, James R, Hammond VE, Kontgen F: Homeosis and intestinal tumours in Cdx2 mutant mice. Nature 1997, 386:84-87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck F, Chawengsaksophak K, Waring P, Playford RJ, Furness JB: Reprogramming of intestinal differentiation and intercalary regeneration in Cdx2 mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999, 96:7318-7323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ee HC, Erler T, Bhathal PS, Young GP, James RJ: Cdx-2 homeodomain protein expression in human and rat colorectal adenoma and carcinoma. Am J Pathol 1995, 147:586-592 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yagi OK, Akiyama Y, Yuasa Y: Genomic structure and alterations of homeobox gene CDX2 in colorectal carcinomas. Br J Cancer 1999, 79:440-444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wicking C, Simms LA, Evans T, Walsh M, Chawengsaksophak K, Beck F, Chenevix-Trench G, Young J, Jass J, Leggett B, Wainwright B: CDX2, a human homologue of Drosophila caudal, is mutated in both alleles in a replication error positive colorectal cancer. Oncogene 1998, 17:657-659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.da Costa LT, He TC, Yu J, Sparks AB, Morin PJ, Polyak K, Laken S, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW: CDX2 is mutated in a colorectal cancer with normal APC/beta-catenin signaling. Oncogene 1999, 18:5010-5014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kessis TD, Silberman MA, Sherman M, Hedrick L, Cho KR: Rapid identification of patient specimens with microsatellite DNA markers. Mod Pathol 1996, 9:183-188 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki Y, Orita M, Shiraishi M, Hayashi K, Sekiya T: Detection of ras gene mutations in human lung cancers by single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis of polymerase chain reaction products. Oncogene 1990, 5:1037-1043 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boland CR, Thibodeau SN, Hamilton SR, Sidransky D, Eshleman JR, Burt RW, Meltzer SJ, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Fodde R, Ranzani GN, Srivastava S: A National Cancer Institute Workshop on Microsatellite Instability for cancer detection and familial predisposition: development of international criteria for the determination of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 1998, 58:5248-5257 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herman JG, Umar A, Polyak K, Graff JR, Ahuja N, Issa JP, Markowitz S, Willson JK, Hamilton SR, Kinzler KW, Kolodner RD, Vogelstein B, Kunkel TA, Baylin SB: Incidence and functional consequences of hMLH1 promoter hypermethylation in colorectal carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998, 95:6870-6875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kane MF, Loda M, Gaida GM, Lipman J, Mishra R, Goldman H, Jessup JM, Kolodner R: Methylation of the hMLH1 promoter correlates with lack of expression of hMLH1 in sporadic colon tumors and mismatch repair-defective human tumor cell lines. Cancer Res 1997, 57:808-811 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaves P, Cruz C, Lage P, Claro I, Cravo M, Leitao CN, Soares J: Immunohistochemical detection of mismatch repair gene proteins as a useful tool for the identification of colorectal carcinoma with the mutator phenotype. J Pathol 2000, 191:355-360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sparks AB, Morin PJ, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW: Mutational analysis of the APC/β-catenin/Tcf pathway in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 1998, 58:1130-1134 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morin PJ, Sparks AB, Korinek V, Barker N, Clevers H, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW: Activation of β-catenin-Tcf signaling in colon cancer by mutations in β-catenin or APC. Science 1997, 275:1787-1790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Munemitsu S, Albert I, Souza B, Polakis P: Regulation of intracellular beta-catenin levels by the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor-suppressor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995, 92:3046-3050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Webster MT, Rozycka M, Sara E, Davis E, Smalley M, Young N, Dale TC, Wooster R: Sequence variants of the axin gene in breast, colon, and other cancers: an analysis of mutations that interfere with GSK3 binding. Genes Chromosom Cancer 2000, 28:443-453 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu W, Dong X, Mai M, Seelan RS, Taniguchi K, Krishnadath KK, Halling KC, Cunningham JM, Boardman LA, Qian C, Christensen E, Schmidt SS, Roche PC, Smith DI, Thibodeau SN: Mutations in AXIN2 cause colorectal cancer with defective mismatch repair by activating beta-catenin/TCF signalling. Nat Genet 2000, 26:146-147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bos JL, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, Verlaan-de Vries M, van Boom JH, van der Eb AJ, Vogelstein B: Prevalence of ras gene mutations in human colorectal cancers. Nature 1987, 327:293-297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ionov Y, Peinado MA, Malkhosyan S, Shibata D, Perucho M: Ubiquitous somatic mutations in simple repeated sequences reveal a new mechanism for colonic carcinogenesis. Nature 1993, 363:558-561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thibodeau SN, Bren G, Schaid D: Microsatellite instability in cancer of the proximal colon. Science 1993, 260:816-819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marra G, Boland CR: DNA repair and colorectal cancer. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1996, 25:755-772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jessurun J, Romero-Guadarrama M, Manivel JC: Cecal poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, medullary type. Mod Pathol 1992, 5:43A [Google Scholar]