Abstract

The most important factor in predicting outcome in patients with early breast cancer is the stage of the disease. There is no robust marker capable of identifying invasive carcinomas that despite their small size have a high metastatic potential, and that would benefit from more aggressive treatment. RhoC-GTPase is a member of the Ras-superfamily and is involved in cell polarity and motility. We hypothesized that RhoC expression would be a good marker to identify breast cancer patients with high risk of developing metastases, and that it would be a prognostic marker useful in the clinic. We developed a specific anti-RhoC antibody and studied archival breast tissues that comprise a broad spectrum of breast disease. One hundred eighty-two specimens from 164 patients were used. Immunohistochemistry was performed on formalin-fixed tissues. Staining intensity was graded 0 to 3+ (0 to 1+ was considered negative and 2 to 3+ was considered positive). RhoC was not expressed in any of the normal, fibrocystic changes, atypical hyperplasia, or ductal carcinoma in situ, but was expressed in 36 of 118 invasive carcinomas and strongly correlated with tumor stage (P = 0.01). RhoC had high specificity (88%) in detecting invasive carcinomas with metastatic potential. Of the invasive carcinomas smaller than 1 cm, RhoC was highly specific in detecting tumors that developed metastases. RhoC expression was associated with negative progesterone receptor and HER-2/neu overexpression. We characterized RhoC expression in human breast tissues. RhoC is specifically expressed in invasive breast carcinomas capable of metastasizing, and it may be clinically useful in patients with tumors smaller than 1 cm to guide treatment.

Breast cancer is the most common type of life-threatening cancer, and the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths of women in the Western world. The most important factor in predicting patient outcome is the stage of the disease. 1-3 Although in general, the more aggressive, the more rapidly growing, and the larger the primary neoplasm, the greater the likelihood that it will metastasize or already has metastasized, this is not always the case. There are many small breast cancers with a highly aggressive behavior and discouraging outcome that remain undertreated because there is no marker capable of identifying them.

RhoC-GTPase is a member of the Ras-superfamily of small guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases). Activation of Rho proteins leads to assembly of the actin-myosin contractile filaments into focal adhesion complexes that lead to cell polarity and facilitate motility. 4-6 Our laboratory has detected overexpression of RhoC mRNA in advanced breast cancers by in situ hybridization, and subsequently characterized RhoC as a transforming oncogene for human mammary epithelial cells, whose overexpression results in a highly motile and invasive phenotype that recapitulates the most lethal form of locally advanced breast cancer, inflammatory breast cancer.

We hypothesized that, given the known functions of the RhoC proteins, RhoC expression would be a good marker to identify breast cancer patients with highly aggressive and motile tumors and guide therapeutic interventions before the development of metastases. Immunohistochemistry is a reproducible and technically simple procedure that would allow testing for RhoC protein expression in the clinical setting. We set out to characterize the expression of RhoC protein in normal, benign, premalignant, and malignant breast disease, with special focus on small (<1 cm) invasive carcinomas with high metastatic potential and/or known metastases.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Specimens

We evaluated 182 specimens from 164 patients. Breast tissues were obtained from surgical resections and biopsies from the breast and sites of distant metastases. These cases were selected from the surgical pathology files at the University of Michigan, reviewed by the study pathologist (CGK), and placed in the following pathological categories: normal breast parenchyma (5 cases), fibrocystic changes (5 cases), fibroadenomas (3 cases), atypical ductal hyperplasia (7 cases), ductal carcinoma in situ (11 cases), invasive ductal carcinoma (114 cases), other types of invasive carcinoma (lobular, 13 cases; mucinous, 6 cases; medullary, 2 cases). In addition, 16 metastatic deposits were analyzed, 9 of which had their corresponding primary tumor to compare. Invasive carcinomas were subdivided by stage into stages I, II, III, and IV. Hormonal receptor status and immunohistochemical staining for HER2/neu was available for most patients. Clinical follow-up information was available for all patients. Patient identifiers were removed for subsequent analyses.

Development of RhoC-Specific Antibody

Because RhoC-GTPase has high homology to other members of the Rho family, RhoA and RhoB, both at the cDNA and the protein level, most available antibodies are cross-reactive with RhoA, RhoB, and RhoC. To attempt to develop an antibody specific for RhoC and not for other Rho family members, a peptide representing a unique epitope was synthesized at the University of Michigan Protein Core. The C-terminal region peptide (GLVQVRKNKRRRGCPIL) was chosen because of its uniqueness and antigenic potential. After injection in rabbits, immune sera were obtained following standard techniques. Western blot confirmed the specificity of the antibody for RhoC (Figure 1) ▶ . Specifically no cross-reaction was observed to recombinant RhoA. To further prove the high specificity of the antibody for RhoC protein, we performed a competition assay by incubating the anti-RhoC antibody with increasing concentrations of the RhoC peptide in 6 ml of 0.3% bovine serum albumin for 6 hours at 4°C. Subsequently a Western blot was performed following standard procedures (Figure 2A) ▶ . As illustrated in Figure 2B ▶ , the specificity of the antibody was also checked by blocking the binding by incubating overnight with a 10-fold molar excess of the RhoC peptide.

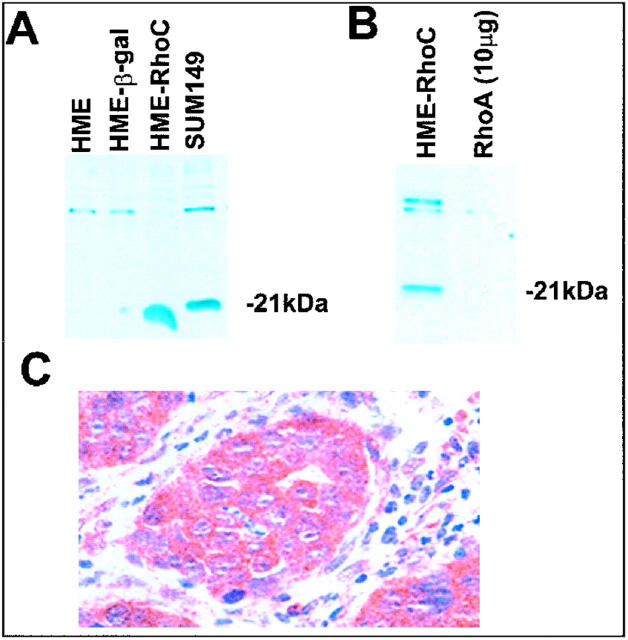

Figure 1.

Development of specific RhoC antibody. A: Western immunoblot showing the specificity of the RhoC antibody for RhoC, without cross-reaction with recombinant RhoA, shown in B. C: Immunohistochemistry using RhoC antibody in a tumor xenograft developed by injecting human mammary epithelial cells overexpressing RhoC in the mammary fat pad of female athymic nude mice. Strong staining of the cytoplasm of the neoplastic cells. HME, human mammary epithelial cells; HME-β-gal, transfection controls; HME-RhoC, HME cells transfected with RhoC gene; SUM149, cell line derived from a patients with inflammatory breast cancer that overexpresses RhoC.

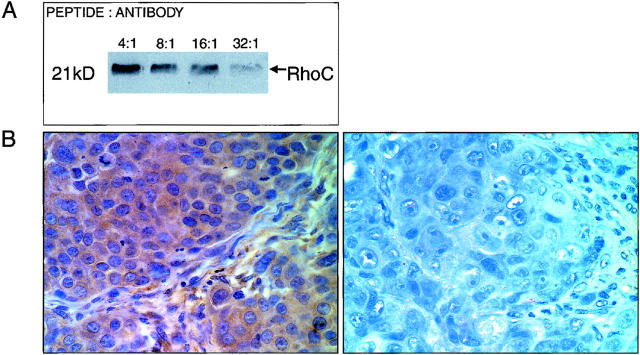

Figure 2.

Demonstration of the specificity of the anti-RhoC antibody. A: Western immunoblot with increasing peptide:antibody concentrations. B: Competition assay by immunohistochemistry before (left) and after (right) addition of a 10-fold molar excess of RhoC peptide (original magnification, ×400).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections that were cut 4-μm thick and stained with polyclonal anti-RhoC antibody. The antibody was titered and used at a 1:1500 dilution for 30 minutes at room temperature, with no previous antigen retrieval. The detection reaction followed the DAKO Envision+ System peroxidase kit protocol (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA). Diaminobenzidine was used as chromogen and hematoxylin was used as counter stain. As positive controls we used tumor xenografts from a cell line known to overexpress RhoC (SUM 149) and from human mammary epithelial cells transfected with RhoC, and patient tumor specimens previously demonstrated to overexpress RhoC by in situ hybridization. 7 Negative controls were done by omitting the primary antibody.

Interpretation of Stains

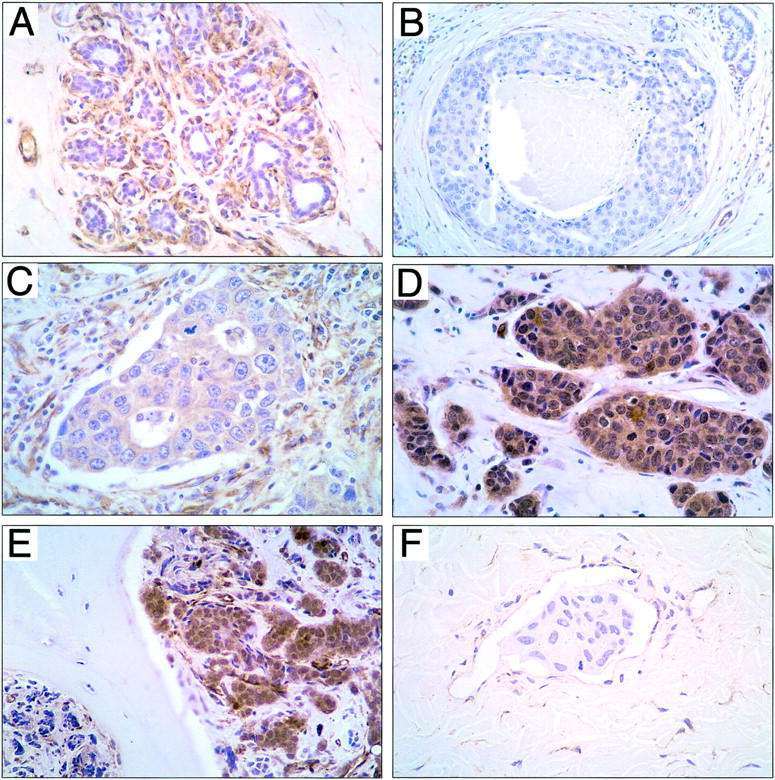

Because RhoC protein interacts with the contractile cytoskeleton of the cell and is localized to the submembrane space, cytoplasmic stain was expected. Not surprisingly, myoepithelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells were strongly positive in all cases, serving as consistent internal positive controls (Figure 3) ▶ . The intensity of cytoplasmic staining was scored as 0 to 3+, by comparison to the positive internal controls. This scoring system has been previously validated. 7,8 Diffuse, moderate to strong cytoplasmic staining characterized RhoC-positive cells (scores 2+ and 3+) (Figure 3; C, D, and E ▶ ). RhoC-negative cells were devoid of any cytoplasmic staining or contained faint, equivocal staining (scores 0 and 1+) (Figure 3, B and F) ▶ .

Figure 3.

Results of RhoC protein detection by immunohistochemistry. A: Normal terminal duct lobular unit showing RhoC staining in the myoepithelial cells and vessels in contrast to the negative normal epithelial cells. B: High-grade ductal carcinoma in situ with central necrosis and no RhoC expression. Note the positive staining of the surrounding blood vessels and occasional myoepithelial cell that serve as positive internal controls. C: Primary invasive ductal carcinoma that measures 0.6 cm with RhoC protein expression (2+). This carcinoma developed axillary lymph node metastases. D: Primary stage 3 invasive ductal carcinoma with strong (3+) cytoplasmic staining for RhoC protein. E: Metastatic ductal carcinoma from the breast to the iliac bone showing strong RhoC expression. F: Intralymphatic carcinomatous embolus in a dermal lymphatic vessel in a patient with the clinical and pathological features of inflammatory breast cancer with no RhoC protein expression. Note the positive staining of the endothelial cells.

Statistical Analysis

The chi-square test was used to assess differences in RhoC expression between invasive carcinoma of different stages. Fisher’s exact test was used to study the relationship between RhoC expression and development of metastases, to study whether RhoC expression was significantly different in inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) primary tumors versus lymphatic emboli, and to determine the association between RhoC expression and estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2/neu status.

Results

RhoC Is Not Expressed in Normal Breast, Fibrocystic Changes, or Preinvasive Breast Disease

We studied five cases of normal breast parenchyma and five cases of fibrocystic changes obtained from reduction mammoplasties and breast biopsies, respectively. RhoC was not detectably expressed in the ductal epithelium in any cases (Figure 3A) ▶ . In addition, the three fibroadenomas tested revealed no RhoC protein expression. No RhoC protein expression was seen in any cases of atypical ductal hyperplasia (seven cases) low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (6 cases), or high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (five cases) (Figure 3B) ▶ . All cases however had consistent and strong RhoC staining of myoepithelial cells and vascular smooth muscle, which served as internal positive control (Figure 3) ▶ .

RhoC Is Expressed in Invasive Carcinomas with Metastases and its Expression Increases with Primary Tumor Stage

Moderate and strong RhoC protein expression (scores 2+ and 3+) was detected in 36 of the 114 (32%) primary invasive ductal carcinomas. When invasive ductal carcinomas were categorized by stage, a strong correlation was found between RhoC protein expression and tumor stage (chi-square test, P = 0.01) (Figure 4) ▶ . The relationship of RhoC expression to the development of metastases is illustrated in Figure 5 ▶ . Of the 36 invasive ductal carcinomas that expressed RhoC, 30 (83%) had axillary lymph node or distant metastases, and 6 (17%) did not metastasize. The specificity and sensitivity of RhoC in predicting the development of metastases was 88% and 47%, respectively. The positive and negative predictive values were 83% and 56%, respectively.

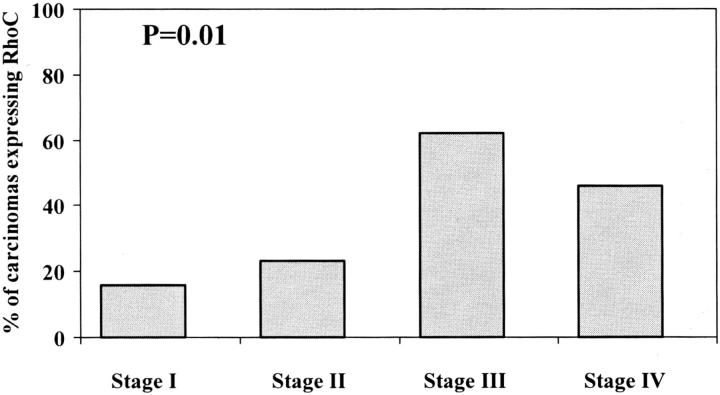

Figure 4.

Increasing RhoC expression with increasing stage of the invasive breast carcinoma.

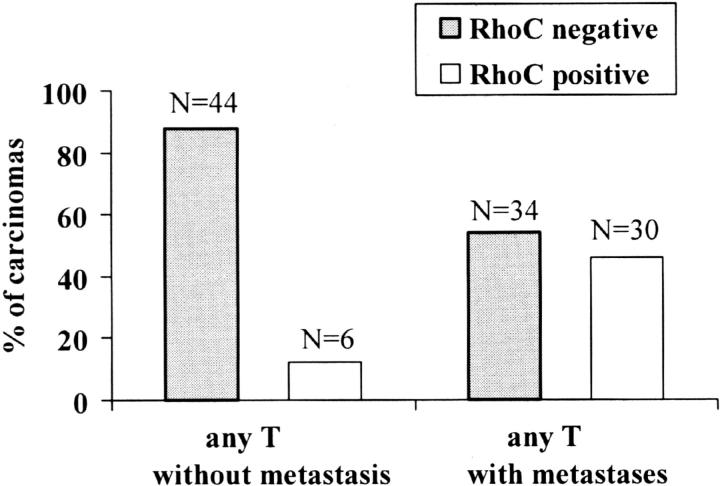

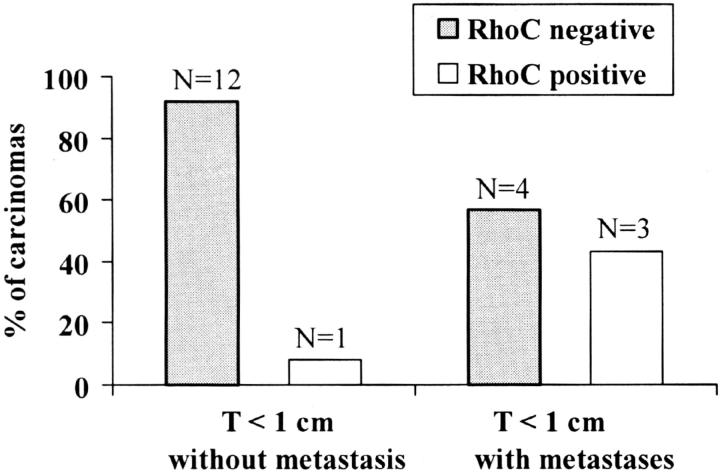

Figure 5.

RhoC expression and development of metastasis. RhoC demonstrated a specificity of 88% and a sensitivity of 47% in detecting invasive carcinomas that metastasized.

Eighty percent of primary IBCs expressed RhoC protein. The intralymphatic tumor emboli seen in the skin biopsies obtained from IBC patients however were negative (Fisher’s exact test, P < 0.001) (Figure 2F) ▶ . Regardless of the pathological tumor stage, RhoC expression was not detected in primary invasive lobular carcinoma, invasive typical medullary carcinomas, or invasive mucinous (colloid) carcinomas.

RhoC Expression in Small Invasive Carcinomas with High Metastatic Potential

When invasive ductal carcinomas were separated by primary tumor size, 20 tumors (18%) were smaller than 1 cm (Figure 6) ▶ . Of these, 13 had no metastases, 6 metastasized to axillary lymph nodes, and 1 developed metastases to axillary lymph nodes and colon. RhoC was moderately (2+) expressed in 3 of 7 (43%) tumors that metastasized and not expressed in 12 of 13 (92%) invasive carcinomas that did not metastasize (Fisher’s exact test P = 0.10) (Figure 6) ▶ . RhoC had a specificity of 92% and a sensitivity of 43% in detecting tumors that have metastatic ability. RhoC’s positive and negative predictive values were 75%.

Figure 6.

RhoC expression identifies a group of invasive ductal carcinomas smaller than 1 cm that developed axillary lymph node and distant metastases. RhoC demonstrated a specificity of 92% and a sensitivity of 43% in detecting invasive carcinomas smaller than 1 cm that metastasized.

RhoC Protein Expression in Breast Cancer Metastases

Of the 14 distant metastases [liver (n = 3), cerebellum (n = 1), bone (n = 4), bone marrow (n = 1), lung (n = 2), large intestine (n = 2), ovary (n = 1), and uterus (n = 1)], 7 (50%) expressed RhoC protein (Figure 2E) ▶ . After these cases were categorized by histological type, RhoC was expressed in five of eight (62.5%) metastases from invasive ductal carcinomas, in two of five (40%) metastases from invasive lobular carcinomas, and it was negative in the one metastasis from a medullary carcinoma.

RhoC Expression Is Associated with Negative Progesterone Receptor and Overexpression of HER2/neu

Table 1 ▶ summarizes the results. We observed that tumors that expressed RhoC were more frequently negative for progesterone receptor, and overexpressed Her-2/neu by immunohistochemistry. Although the associations did not reach statistical significance they suggest that RhoC expression seems to be associated with well-known predictors of patient outcome. No association was found between RhoC and estrogen receptor expression.

Table 1.

Relationship between RhoC Protein Detection by Immunohistochemistry, Estrogen and Progesterone Receptor Status, and HER-2/neu Overexpression

| RhoC protein expression | P* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (0–1+) | Positive (2–3+) | ||

| Estrogen receptor, n (%) | |||

| Negative | 21 (64%) | 12 (36%) | 0.49 |

| Positive | 51 (72%) | 20 (28%) | |

| Progesterone receptor, n (%) | |||

| Negative | 29 (62%) | 18 (38%) | 0.14 |

| Positive | 43 (75%) | 14 (25%) | |

| HER-2/neu, n (%) | |||

| Not overexpressed | 39 (83%) | 8 (17%) | 0.08 |

| Overexpressed | 28 (67%) | 14 (33%) | |

*P, Fisher’s exact test.

Discussion

The Rho (Ras homology) gene was first isolated from aplysia and has been shown to be highly conserved throughout evolution. RhoC-GTPase is involved in cytoskeletal reorganization, specifically in the formation of actin stress fibers and focal adhesion contacts. 4-6 Our laboratory has recently demonstrated that RhoC is overexpressed in IBC tumors by in situ hybridization, 9 and has shown that overexpression of RhoC induced the malignant transformation of immortalized human mammary epithelial cells by producing an aggressive, highly motile, and invasive phenotype that partially recapitulates the behavior of IBC in humans. 10

Based on these results, we hypothesized that expression of RhoC would identify invasive carcinomas that despite their small size have a highly invasive and metastatic potential, and thus develop into a useful screening tool to be used in the clinical arena. We also hypothesized that RhoC may be a new prognostic marker in patients with breast cancer. To test our hypotheses, we developed a specific and sensitive polyclonal antibody directed against the RhoC protein that can be used for immunohistochemistry, and set out to characterize RhoC protein expression in a wide spectrum of breast pathology, from normal, benign lesions, premalignant and in situ carcinomas, to invasive carcinomas of the breast.

From our results several important conclusions can be drawn. First, RhoC expression may not be an early event in the development of non-IBC breast cancer, but a later genetic alteration that occurs once the cancer cells have acquired invasive capabilities. We showed that RhoC is exclusively expressed in invasive carcinomas and not in normal breast, atypical intraductal hyperplasia, or ductal carcinoma in situ. In IBC, the most lethal type of locally advanced breast cancer that is highly metastatic from its inception, RhoC seems to occur early in its development because 80% of all primary IBCs expressed the protein. These results support our previous observations that RhoC is consistently overexpressed in IBC. 9 Interestingly, none of the dermal lymphatic tumor emboli expressed RhoC. A possible explanation may be that endolymphatic tumor emboli are cohesive clumps of cancer cells and do not need to acquire motile capabilities until they reach the site of metastases, at which point the tumor cells extravasate and invade new tissues. This argument is supported by a previous study from our laboratory that showed that intralymphatic tumor emboli strongly express E-cadherin, an epithelial cell-cell adhesion molecule that enables the cancer cells to form tightly cohesive tumor emboli. 11

Second, RhoC seems to be a marker of metastatic potential in breast cancer. We demonstrated that nearly half of the invasive ductal carcinomas that developed metastases expressed RhoC (30 of 64 cases, 47%), in contrast to very few of the invasive carcinomas without metastases (6 of 50 cases, 12%). RhoC demonstrated a high specificity (88%) in detecting which tumors have the ability to metastasize. These results are in concordance with previous data showing that overexpression of RhoC-GTPase in immortalized human mammary epithelial cells leads to a motile and invasive phenotype able to develop highly metastatic tumors when injected in nude mice. 10 Not surprisingly, we found that RhoC-GTPase expression increases with the stage of the invasive carcinoma.

Third, our results suggest that RhoC protein detection by IBC may be a useful tool capable of identifying small invasive ductal carcinomas with high propensity to metastasize. Although the number of cases in our study is small, RhoC was highly specific (specificity of 92%) in detecting small invasive carcinomas with metastatic potential. Forty-three percent of invasive carcinomas smaller than 1 cm that developed metastases expressed RhoC protein, in contrast to 8% of the small tumors that did not metastasize. We are currently expanding the number of cases to further define these observations. This potential use of RhoC in the clinical setting may have a profound impact in the management of breast cancer patients. Specifically, detection of RhoC expression may identify patients who will benefit from an axillary lymph node dissection given the high risk of metastases. RhoC expression may also suggest the use of chemotherapy in patients with small invasive carcinomas at high risk of metastases.

Our data revealed an association between RhoC expression, Her-2/neu overexpression, and loss of progesterone receptor in invasive ductal carcinomas, both well-established predictors of patient outcome. Although primary invasive lobular carcinomas did not express RhoC, 40% of their distant metastases expressed the protein, suggesting that RhoC expression may be involved in the metastatic process of this type of invasive carcinoma, but may be a later event than in non-IBC invasive ductal carcinomas. RhoC expression does not seem to play a role in the late stages of other uncommon forms of invasive breast cancer, including medullary and colloid (mucinous) carcinomas.

Because RhoC protein is associated with the contractile cytoskeleton of the cell, it is not surprising that it is detected by immunohistochemistry in myoepithelial cells and in the vascular smooth muscle cells. These two cell types served as consistent and strong (3+) internal positive controls for the antibody and were detected in all cases.

This study is the first examining the expression of RhoC-GTPase protein in a wide spectrum of normal breast and of breast disease. It is clear from the results that RhoC is a specific marker of metastatic disease in patients with breast cancer. Importantly, although our data are preliminary, it appears to identify a subset of patients with small primary tumors and high metastatic potential that would benefit from axillary lymph node staging and/or chemotherapy and that would remain otherwise unrecognized.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elizabeth Horn for artwork and Kent A. Griffith for statistical support.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Celina G. Kleer, M.D., Department of Pathology, 2G332 University Hospital, 1500 E. Medical Center Dr., Ann Arbor, MI 48109-0054. E-mail: kleer@umich.edu.

Supported in part by DOD grant DAMD17-00-1-0636 (C.G.K.), NIH grant R01CA77612 (S.D.M.), MUNN award from University of Michigan (C.G.K.), DOD grant DAMD 17-00-1-0637 (K.v.G.), and DOD grant DAMD 17-00-1-0345 (S.D.M.).

References

- 1.Danforth D, Lichter AS, Lippmann ME: The diagnosis of breast cancer. Danforth D Lichter AS Lippmann ME eds. Diagnosis and Management of Breast Cancer. 1988, :pp 50-94 W.B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosen PR, Groshen S, Saigo PE, Kinne DW, Hellman S: A long-term follow-up study of survival in stage I (T1N0M0) and stage II (T1N1M0) breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 1989, 7:355-366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haybittle JL, Blamey RW, Elston CW, Johnson J, Doyle PJ, Campbell FC, Nicholson RI, Griffiths K: A prognostic index in primary breast cancer. Br J Cancer 1982, 45:361-366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nobes CD, Hall A: Rho, rac, and cdc42 GTPases regulate the assembly of multimolecular focal complexes with actin stress fibers, lamellipodia and filopodia. Cell 1995, 81:53-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leung T, Chen XQ, Manser E, Lim L: The p160 RhoA-binding kinase ROK alpha is a member of a kinase family and is involved in the reorganization of the cytoskeleton. Mol Cell Biol 1996, 16:5313-5327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimura K, Ito M, Amano M, Chihara K, Fukata Y, Nakafuku M, Yamamori B, Feng J, Nakano T, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Kaibuchi K: Regulation of myosin phosphatase by Rho and Rho-associated kinase (Rho-kinase) Science 1996, 273:245-248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Golen KL, Davies S, Wu ZF, Wang Y, Bucana CD, Root H, Chandrasekharappa S, Strawderman M, Ethier SP, Merajver SD: A novel putative low-affinity insulin-like growth factor-binding protein, LIBC (lost in inflammatory breast cancer), and RhoC-GTPase correlate with the inflammatory breast cancer phenotype. Clin Cancer Res 1999, 5:2511-2519 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mucci NR, Akdas G, Manely S, Rubin MA: Neuroendocrine expression in metastatic prostate cancer: evaluation of high throughput tissue microarrays to detect heterogeneous protein expression. Hum Pathol 2000, 31:406-414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vallorosi CJ, Day KC, Zhao X, Rashid MG, Rubin MA, Johnson KR, Wheelock MJ, Day ML: Truncation of the beta-catenin binding domain of E-cadherin precedes epithelial apoptosis during prostate and mammary involution. J Biol Chem 2000, 275:3328-3334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Golen KL, Wu ZF, Qiao XT, Bao LW, Merajver SD: RhoC-GTPase, a novel transforming oncogene for human mammary epithelial cells that partially recapitulates the inflammatory breast cancer phenotype. Cancer Res 2000, 60:5832-5838 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleer CG, van Golen KL, Braun T, Merajver SD: Persistent E-cadherin expression in inflammatory breast cancer. Mod Pathol 2001, 14:458-464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]