Abstract

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and neuroblastoma (NB), the most aggressive adult and infant neuroendocrine cancers, respectively, are immunologically characterized by a severe reduction in major histocompatibility complex (MHC) that is indispensable for anti-tumor immunity. We had reported that the severe reduction of MHC in SCLC was caused by a deficient interferon (IFN)-γ-inducible expression of class II transactivator (CIITA) that is known as a very important transcription factor for IFN-γ-inducible class II and class I MHC expression (Yazawa T, Kamma H, Fujiwara M, Matsui M, Horiguchi H, Satoh H, Fujimoto M, Yokohama K, Ogata T: Lack of class II transactivator causes severe deficiency of HLA-DR expression in small cell lung cancer. J Pathol 1999, 187:191–199). Here, we demonstrate that the reduction of MHC in NB was also caused by a deficient IFN-γ-inducible expression of CIITA and that the deficiency in SCLC and NB was caused by similar mechanisms. Human achaete-scute complex homologue (HASH)-1, L-myc, and N-myc, which are specifically overexpressed in SCLC and NB, bound to the E-box in CIITA promoter IV and reduced the transcriptional activity. Anti-sense oligonucleotide experiments revealed that overexpressed L-myc and N-myc lie upstream in the regulatory pathway of HASH-1 expression. The expression of HASH-1 was also up-regulated by IFN-γ. Our results suggest that SCLC and NB have complicated mechanisms of IFN-γ-inducible CIITA transcription deficiency through the overexpressed HASH-1, L-myc, and N-myc. These complicated mechanisms may play an important role in the escape from anti-tumor immunity.

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and neuroblastoma (NB) are the most aggressive adult and infant neuroendocrine neoplasms, respectively. 1,2 Both are less associated with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, which are morphological findings of anti-tumor immunity, and show a more severe reduction in major histocompatibility complex (MHC) than nonneuroendocrine cancers. 3-5 The MHC expressed on the cell surface is indispensable for contact with T lymphocytes. Class I MHC (MHC-I) expressed on cancer cells plays an important role in the killer T lymphocyte-mediated immune response. Class II MHC (MHC-II) expressed on cancer cells could present antigenic peptides to helper T lymphocytes and could contribute to anti-tumor immunity as well as nonprofessional antigen-presenting cells such as endothelial cells. 6-9 The immune systems of neuroendocrine cancer-laden hosts are therefore not considered to function well.

The expression mechanisms of MHC have recently been clarified. Nucleated cells constitutively express varying amounts of MHC-I. Although nonimmune competent cells hardly express MHC-II constitutively, several cytokines induce MHC-II in nonimmune competent cells. Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), the most powerful MHC inducer, evokes both MHC-I and MHC-II expression. 10 Therefore, IFN-γ is now widely used for immunotherapy against cancers such as melanomas. 11 It has been clarified that RFX5, RFXAP, RFXB, CREB1, NF-Y, and class II transactivator (CIITA) are responsible for gene activation of MHC-II. 12 CIITA, one of the bare lymphocyte syndrome genes, 12 is not only a master transcription factor for the IFN-γ-inducible MHC-II expression but also very important for MHC-I expression. 13,14 Different cellular compartments are controlled by the differential usage of the CIITA promoters, and the epithelial cells use promoter IV for the IFN-γ-inducible expression of CIITA. 15 CIITA promoter IV has three specific transcription factor-binding sites, the IFN-γ-activating site (GAS), the E-box (CACGTG sequence), and the IFN regulatory factor (IRF)-binding site. 15,16 The binding of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-1α, upstream stimulatory factor (USF)-1, and IRF-1 to the respective binding site is crucial for transcription of CIITA. 16

Immature neuronal and neuroendocrine cells express unique transcription factors with a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) structure such as human achaete-scute complex homologue (HASH)-1, L-myc, and N-myc. The expression of HASH-1 is physiologically restricted to neuronal and neuroendocrine cells in the early stages of development, and therefore HASH-1 is expected to be associated with the determination of cell fate. 17-19 Fetal nervous and neuroendocrine tissues express much L-myc and N-myc, which are considered to be involved in regulating cell proliferation and differentiation. 20,21 Neuroendocrine cancers specifically overexpress HASH-1. 17 SCLC and NB are known to involve gene amplification and/or overexpression of L-myc and N-myc, respectively. 22,23 The amplification of N-myc has been used clinically as a prognostic factor for a poor outcome in patients with NB. 2 However, the precise relation between the overexpression of these bHLH transcription factors and disease initiation/progression has been controversial. 23

We recently clarified that SCLC, among various histological types of lung cancer, showed a severe reduction of MHC caused by a deficiency of CIITA expression. 4 Because a reduction of MHC has also been reported in NB 7 and because the E-box, the consensus binding motif of HASH-1, L-myc, and N-myc, 22 is located in CIITA promoter IV, it has been proposed that NB also has a deficiency of CIITA and the bHLH transcription factors overexpressed in SCLC and NB modulate the IFN-γ-inducible CIITA expression. This study demonstrates that the overexpressed HASH-1, L-myc, and N-myc in SCLC and NB competitively bind to the E-box in CIITA promoter IV and repress the transcriptional activity, that IFN-γ up-regulates HASH-1 expression, and that L-myc and N-myc are involved in HASH-1 expression. Therefore, it is considered that SCLC and NB fatefully have complicated molecular mechanisms that negatively affect CIITA expression.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Cell Culture

The human SCLC cell lines (TKB15, TKB16, and TKB17), 4 and the human NB cell lines (LA-N-1, LA-N-2, and LA-N-5) (purchased from Riken Cell Bank, Tsukuba, Japan), NH12 (provided by Cell Resource Center for Biomedical Research, Institute of Development, Aging, and Cancer, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan), and SK-N-DZ (kindly provided by Dr. M. Kaneko, Department of Pediatric Surgery, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Japan), were grown in RPMI 1640 medium. The human nonneuroendocrine cancer cell lines, TKB5 (large cell lung cancer) 4 and HeLa (purchased from Riken Cell Bank), were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium. Both media were supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, and cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. Recombinant IFN-γ (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA) was added at 100 IU/ml for the CIITA and MHC induction experiments. 4

RNAs, Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR), and Northern Blotting

RT-PCR using a RNA-PCR kit (Takara, Shiga, Japan) was conducted with 1 μg of total RNA. Specific primers for CIITA, NFY-A, NFY-B, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were as described previously. 4 The upper and lower primers for RFX5, RFXAP, RFXB, CREB1, L-myc, N-myc, and HASH-1, which, respectively, amplify 787-bp, 858-bp, 507-bp, 527-bp, 239-bp, 381-bp, and 374-bp cDNA fragments, were as follows: RFX5 upper primer 5′-AACAGAGAGGTAGGCATAGGT-3′ and lower primer 5′-GAAAAGGTCAGAGGCAGCAAC-3′, RFXAP upper primer 5′-AAGAAACACGCAACAAGAT-G-3′ and lower primer 5′-AACACAAAATAGCCATCAA-CA-3′, RFXB upper primer 5′-CTCATCCAGACCCAGCAGACC-3′ and lower primer 5′-CTCCAGCAGCAGCCC-CACAAT-3′, CREB1 upper primer 5′-CCCCAGCACTTCCTACACAGC-3′ and lower primer 5′-TTTCCTCATTTC-TCCCATCAA-3′, L-myc upper primer 5′-TATGACTGC-GGGGAGGATTTC-3′ and lower primer 5′-CGGCGTATGA-TGGAGGCGTAG-3′, N-myc upper primer 5′-GACGC-TTCTCAAAACTGGACA-3′ and lower primer 5′-TCA-AATGGCAAACCCCTTATG-3′, HASH-1 upper primer 5′-CAGCGCCCAAGCAAGTCAAGC-3′ and lower primer 5′-GGCCATGGAGTTCAAGTCGTT-3′. Northern blot analyses using 15 μg of total RNA were performed as described previously. 4 Probes of digoxigenin-labeled HLA-DRα and GAPDH cDNA, which was used for the internal control, were as described. 4 The 402-bp human MHC-I cDNA fragments produced by RT-PCR using specific primers (upper primer 5′-CGACGGCAAGGATTACAT-3′ and lower primer 5′-CCAGAAGGCACCACCACA-3′), which amplify nonpolymorphic regions of MHC-I, were labeled with digoxigenin (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) and used as the probe. RT-PCR products of HASH-1, L-myc, and N-myc, and the c-myc exon 2 fragments (purchased from Takara) were also digoxigenin-labeled and used as probes. Semiquantitative analysis of mRNA levels was performed by NIH image version 1.62.

Construction of HASH-1, L-myc, and N-myc Expression Vectors

The inserts of HASH-1, L-myc, and N-myc expression vectors were constructed using RNA of TKB15 and SK-N-DZ and primer sets specific for the 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions of HASH-1 (upper primer 5′-GATTCCGCGACTCCTTGG-3′ and lower primer 5′-CCTGA-CCAGGCCGAGCCCCTCAGA-3′), L-myc (upper primer 5′-CTGGAGCGAGGGAGCGGACAT-3′ and lower primer 5′-ACTAAAGGGGAGAGGGAGGTT-3′), and N-myc (upper primer 5′-GCTGCTCCACGTCCACCATG-3′ and lower primer 5′-CATGGAGGTGAGGTGGAGGAG-3′). The products were cloned with pT7Blue cloning vector (Novagen, Madison, WI) and sequenced. Each purified HASH-1, L-myc, or N-myc cDNA was inserted into a pZeoSV2 expression vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). HASH-1 was also inserted into a pIRES2 expression vector (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). We used an expression vector for human CIITA (pZeoSV2-CIITA) that was previously constructed. 4 The recombinant proteins for HASH-1, L-Myc, and N-Myc were produced using a T7 promoter-dependent in vitro transcription and translation system (Novagen). The reactions were conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western Blotting

Western blot analyses for HASH-1, L-Myc, N-Myc, Max, E12/E47, USF-1, 701Tyr-phosphorylated STAT-1α, and IRF-1 were conducted using 50 μg of whole cell lysate from cultured cancer cells and anti-mammalian achaete-scute complex homologue (MASH)-1 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), anti-L-Myc (Sigma-Genosys, Cambridge, UK), anti-N-Myc (Sigma-Genosys), anti-Max (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-E12/E47 (Santa Cruz), anti-USF-1 (Santa Cruz), anti-701Tyr-phosphorylated STAT-1 (New England Biolab, Beverly, MA), and anti-IRF-1 (Santa Cruz) antibodies. The cross-reactivity of anti-MASH-1 antibody with HASH-1 was confirmed by immunoprecipitation assay using recombinant HASH-1 protein as mentioned below. The electrophoresed samples were electroblotted on a nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH), and detected with the ECL system (Amersham Pharmacia, Buckinghamshire, UK). Anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was used for the internal control.

Extraction of Nuclear Proteins

TKB15 (a SCLC cell line), SK-N-DZ (a NB cell line), and TKB5 (a non-SCLC cell line) cells were stimulated with IFN-γ (100 IU/ml) for 30 minutes before the preparation of nuclear extract. The following steps were performed at 4°C. The IFN-γ-treated cells were collected and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (154 mmol/L NaCl and 10 mmol/L sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.6) containing 2 mmol/L of MgCl2, and then suspended in isolation buffer [20 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.6, 10 mmol/L NaCl, 0.5 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0.5 mmol/L phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 0.5 μg/ml pepstatin A, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol, and 0.25% Triton X-100]. Nuclei were collected by centrifugation, washed twice with isolation buffer without Triton X-100, and then suspended in extraction buffer (20 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.6, 20 mmol/L NaCl, 0.5 mmol/L EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mmol/L PMSF, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 0.5 μg/ml pepstatin A, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol). Because a highly concentrated salt buffer is necessary for effective extraction of Myc and Max proteins, 24 NaCl was added at up to 1 mol/L in the nuclear suspensions. After gentle agitation for 1 hour at 4°C, the suspensions were layered on the sucrose cushion buffer (20 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.6, 1 mol/L NaCl, 0.5 mmol/L EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mmol/L PMSF, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 0.5 μg/ml pepstatin A, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol, and 30% sucrose) and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 1 hour. The top layer was desalted and concentrated with microcon-10 (Amicon, Beverly, MA) and ddH2O containing 0.5 mmol/L PMSF, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 0.5 μg/ml pepstatin A, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol.

Immunoprecipitation

To analyze the availability of anti-MASH-1 (BD Pharmingen), anti-L-Myc (Sigma-Genosys), and anti-N-Myc (Sigma-Genosys) antibodies for chromatin immunoprecipitation assay, immunoprecipitation and immunoblot studies using respective antibody-conjugated protein G-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden), 50 μl of in vitro transcription translation reactant containing recombinant HASH-1, L-Myc, and N-Myc, and 25 μg of nuclear lysate from TKB15 or SK-N-DZ containing the intrinsic forms were performed. Immunoprecipitation experiments using anti-STAT-1α, anti-USF-1, anti-c-Myc, anti-Max, and anti-E12/E47 (all from Santa Cruz) antibodies, which were used in chromatin immunoprecipitation studies mentioned below, were also performed to examine the ability to specifically immunoprecipitate the respective cognate antigen.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays were essentially performed as described by Moreno and colleagues. 25 TKB15 or SK-N-DZ cells (1 × 107) were exposed to formaldehyde (final concentration, 1%) added directly to the tissue culture medium for 10 minutes. Cells were pelleted and washed in phosphate-buffered saline three times, lysed in lysis buffer [5 mmol/L PIPES (pH 8.0), 85 mmol/L KCl, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40 containing protease inhibitors (1 mmol/L PMSF, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 μg/ml aprotinin)], and incubated on ice for 5 minutes. Nuclei were pelleted and lysed in 500 μl of nuclei lysis buffer [50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.1, 10 mmol/L EDTA, and 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)] containing protease inhibitors. Lysed nuclei were sonicated using a microtip until the average DNA fragment was ∼600 bp. The samples were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 5 minutes and the supernatants (50 μl) were diluted 1:10 with immunoprecipitation dilution buffer (0.01% SDS, 1.1% Triton X-100, 1.2 mmol/L EDTA, 16.7 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.1, and 167 mmol/L NaCl) containing protease inhibitors, 50 μg/ml of yeast tRNA, and 20 μg/ml of sonicated salmon sperm DNA. Immunoprecipitations were performed at 4°C for 2 hours using 550 μl of diluted supernatant and protein G-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia) conjugated with antibody against STAT-1α (Santa Cruz), USF-1 (Santa Cruz), L-Myc (Sigma-Genosys), N-Myc (Sigma-Genosys), Max (Santa Cruz), HASH-1 (BD Pharmingen), or anti-E12/E47 (Santa Cruz). Protein G-Sepharose beads without antibody were used as the negative control. Protein G-Sepharose beads conjugated with immune complexes were washed three times for 10 minutes each with the following buffers: immunoprecipitation dilution buffer, washing buffer A (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mmol/L EDTA, 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.1, and 500 mmol/L NaCl), and washing buffer B (0.1% SDS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 100 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.1, and 500 mmol/L NaCl), followed by a final wash with TE (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 1 mmol/L EDTA). Immune complexes were disrupted with elution buffer (50 mmol/L NaHCO3 and 1% SDS) and the covalent links were reversed by addition of NaCl to a final concentration of 300 mmol/L and heating to 65°C for 6 hours. DNA was ethanol-precipitated and further purified by proteinase K digestion, phenol/chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation. Purified DNA fragments sonicated under the same conditions were used as the positive control. PCR was conducted using Ex Taq polymerase (Takara). The upper and lower primers that amplify CIITA promoter IV including GAS, E-box, and the IRF-binding site, or the 3′ untranslated region of the CIITA gene, which, respectively, amplifies 143-bp and 181-bp DNA fragments, were as follows: CIITA promoter IV upper primer 5′-CAGGGACCTCTTGGATG-3′ and lower primer 5′-CCCCGCAGTTCTTTTTC-3′, 3′ untranslated region upper primer 5′-AGGCCAGAGGGAGTG-ACA-3′ and lower primer 5′-GCTGAAGCAGAAGAATCG-3′.

Electromobility Shift Assay

For the binding reaction with the CIITA promoter IV sequence, 5 μg of nuclear extract was mixed with 5 pmol of digoxigenin-labeled double-stranded CIITA promoter IV-specific DNA probe containing the GAS and the E-box (ProIV) or mutated E-box (ProIVm) sequence in a final volume of 20 μl containing 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 50 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 5% glycerol, 0.75 μg poly dIdC, and 5 mmol/L dithiothreitol. The mixture was incubated 30 minutes at 20°C. The sense sequence of the ProIV probe was 5′-GCCCCAGGCAGTTGGGATGCCACTTCTGATAAAGCACGTGGTGGCCACAG-3′ and the sense sequence of the ProIVm probe was 5′-GCCCCAGGCAGTTGGGATGCCACTTCTGATAAAGGAATTCG-TGGCCACAG-3′. Mutations are underlined. For supershift experiments, antibodies against USF-1 (Santa Cruz), L-Myc (Sigma-Genosys), N-Myc (Sigma-Genosys), HASH-1 (BD Pharmingen), and c-Myc (Santa Cruz) were added to the mixture and left 20 minutes at 4°C before gel electrophoresis in 5% acrylamide/bisacrylamide (29:1) gels with 0.25× TBE buffer for 2 hours at 200 V and 4°C with recirculating buffer. The protein-probe complexes were contact-blotted and fixed with UV for 5 minutes on positively charged nylon membranes (NEN), and the digoxigenin-labeled probes were detected with a chemiluminescence detection kit (Roche Diagnostics).

Transfection of Expression Vectors into TKB5 Cells

The expression vectors were transfected into TKB5, using the lipofection method (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) as previously described, 4 and stable transfectants were obtained after 3 weeks selection. To check the expression of transfected genes, RT-PCR was performed using primers specific for each.

Luciferase Assay

A 416-bp fragment of cloned CIITA promoter IV sequence (−335 to +81) 16 obtained through PCR using specific primers (upper primer 5′-GAAACAGAGACCCACCCA-3′ and lower primer 5′-ACCTACCGCTGTTCCCCG-3′) and a pT7Blue cloning vector (Novagen) were inserted into a PicaGene basic luciferase vector (Toyo Ink, Tokyo, Japan). After 24 hours of subculture (1 × 105 cells/well), the reporter vector and the PicaGene Seapansy SV40 control vector (Toyo Ink) (mol ratio, 150:1) were co-transfected into stably bHLH-transfected TKB5 cells through the lipofection method. Stably empty vector (pZeoSV2-empty, pZeoSV2-empty/pIRES2-empty)-transfected TKB5 cells were used as the control. After 24 hours of incubation, cells were treated with 100 IU/ml of IFN-γ for another 24 hours and harvested. The luciferase activity was measured and normalized according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA).

Synthesis of Oligodeoxy-Nucleoside Phosphorothioates (PS-Oligo) and Forced Repression of HASH-1, L-myc, and N-myc

5′-SH (thiol residue)-added oligodeoxy-nucleoside phosphorothioates (PS-oligo) were synthesized (Nippon Seifun, Kanagawa, Japan). To transfect them more effectively, activated penetratin-1 (Quantum Appligene, Strasbourg, France) was conjugated to their 5′ end. The 15 mer (5′-GGCAGAGCTTTCCAT-3′), the 15 mer (5′-GCCGCCGCTCTCCAT-3′), and the 15 mer (5′-TACCTTTCGAGACGG-3′) were used as anti-sense, sense, and reverse PS-oligos for HASH-1. The 20 mer (5′-TGGTACGAGTCGTAGTCCAT-3′), the 20 mer (5′-ATGGACTACGACTCGTACCA-3′), and the 20 mer (5′-TACCTGATGCTGAGCATGGT-3′) were used as anti-sense, sense, and reverse PS-oligos for L-myc. The 15 mer (5′-GATCATGCCCGGCAT-3′), the 15 mer (5′-ATGCCGGGCATGATC-3′), and the 15 mer (5′-TACGGCCCGTACTAG-3′) were used as anti-sense, sense, and reverse PS-oligos for N-myc. 26 TKB15 or SK-N-DZ cells (2 × 105) were treated with 1 ml of medium containing 20 μmol/L PS-oligos (final concentration) for up to 24 hours and harvested. Because it was confirmed that PS-oligo conjugated with biotinylated penetratin-1 was taken up into the cell nuclei within 30 minutes, the PS-oligo treatment was conducted 1 hour before the IFN-γ treatment.

Results

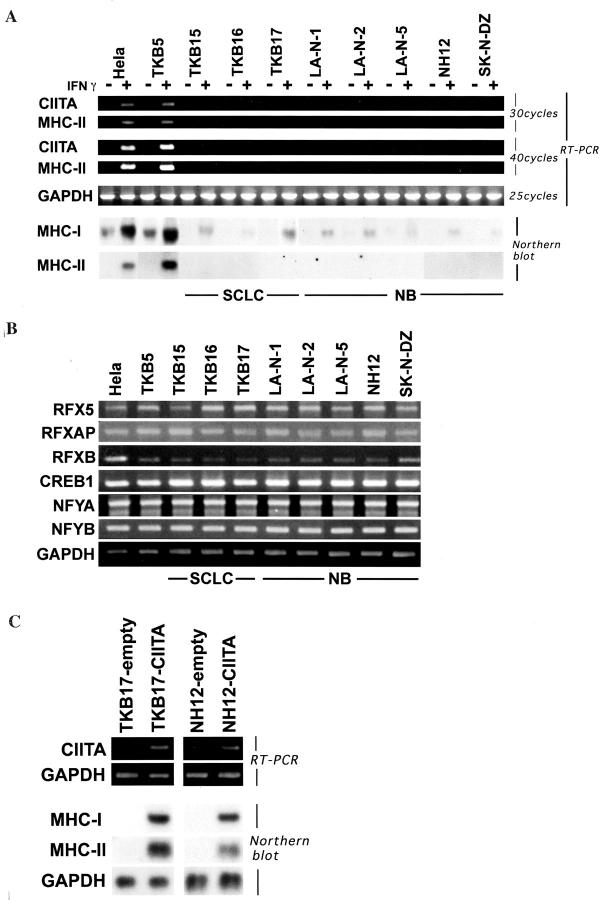

Deficiency of IFN-γ-Inducible CIITA Expression in NB Causes Severe MHC Reduction as in SCLC

We first examined the status of CIITA expression and its induction by IFN-γ in NB, comparing with that in SCLC and in nonneuroendocrine cancers. As shown in Figure 1A ▶ , the IFN-γ treatment easily induced both MHC-I and MHC-II expression in the nonneuroendocrine cancer cell lines, HeLa and TKB5, whereas the NB cell lines showed very little induction of CIITA by IFN-γ as did the SCLC cell lines. The CIITA and MHC-II cDNA products were undetectable by ordinary PCR after reverse transcription even in the IFN-γ-treated condition. The additional rounds of PCR ensured that weak signals were detectable. The SCLC and NB cell lines also showed poor constitutive and IFN-γ-inducible MHC-I expression compared with the nonneuroendocrine cancer cell lines. The other crucial transcription factors for MHC-II expression, RFX5, RFXAP, RFXB, CREB1, and NFY, were expressed well in all SCLC and NB cell lines (Figure 1B) ▶ . Furthermore, both MHC-I and MHC-II expression in NB was improved through the CIITA gene transfection (Figure 1C) ▶ as well as in SCLC as previously described. 4 From these results, it was clarified that the deficient expression of CIITA in NB is responsible for the severe reduction of MHC as in SCLC. However, the SCLC and NB cell lines did not have a deletion of the CIITA gene or mutation of CIITA promoter IV (data not shown). These cell lines exhibited good IFN-γ-inducible IRF-1 expression and immediate phosphorylation of the tyrosine residue of STAT-1α (data partly shown in Figure 3D ▶ ). USF-1, another transcription factor crucial for IFN-γ-inducible CIITA expression, was constitutively expressed not only in nonneuroendocrine cancer but also in SCLC and NB cell lines (data partly shown in Figure 3A ▶ ). These results strongly suggested the existence of neuroendocrine cancer-specific transrepressive mechanisms of CIITA expression.

Figure 1.

Severe deficiency of constitutive and IFN-γ-inducible CIITA/MHC expression in SCLC and NB. A: RT-PCR and Northern blot analyses on constitutive and IFN-γ-inducible expression of CIITA, MHC-I, and MHC-II mRNA. The IFN-γ induction of CIITA and MHC-II is extremely deficient in SCLC and NB cell lines. Both constitutive and IFN-γ-inducible MHC-I expression is also significantly lower in SCLC and NB cell lines than in nonneuroendocrine cancers. B: RT-PCR analyses on MHC-II-specific transcription factors. The other transcription factors crucial for MHC-II, RFX5, RFXAP, RFXB, CREB1, and NFY are constitutively expressed well in SCLC, NB, and nonneuroendocrine cancer cell lines. C: RT-PCR and Northern blot analyses on CIITA and MHC expression in empty vector-transfected (TKB17-empty, NH12-empty) or CIITA-transfected (TKB17-CIITA, NH12-CIITA) cells. MHC-I and MHC-II expression are improved through the CIITA transfection both in TKB17 (SCLC) and NH12 (NB).

Figure 3.

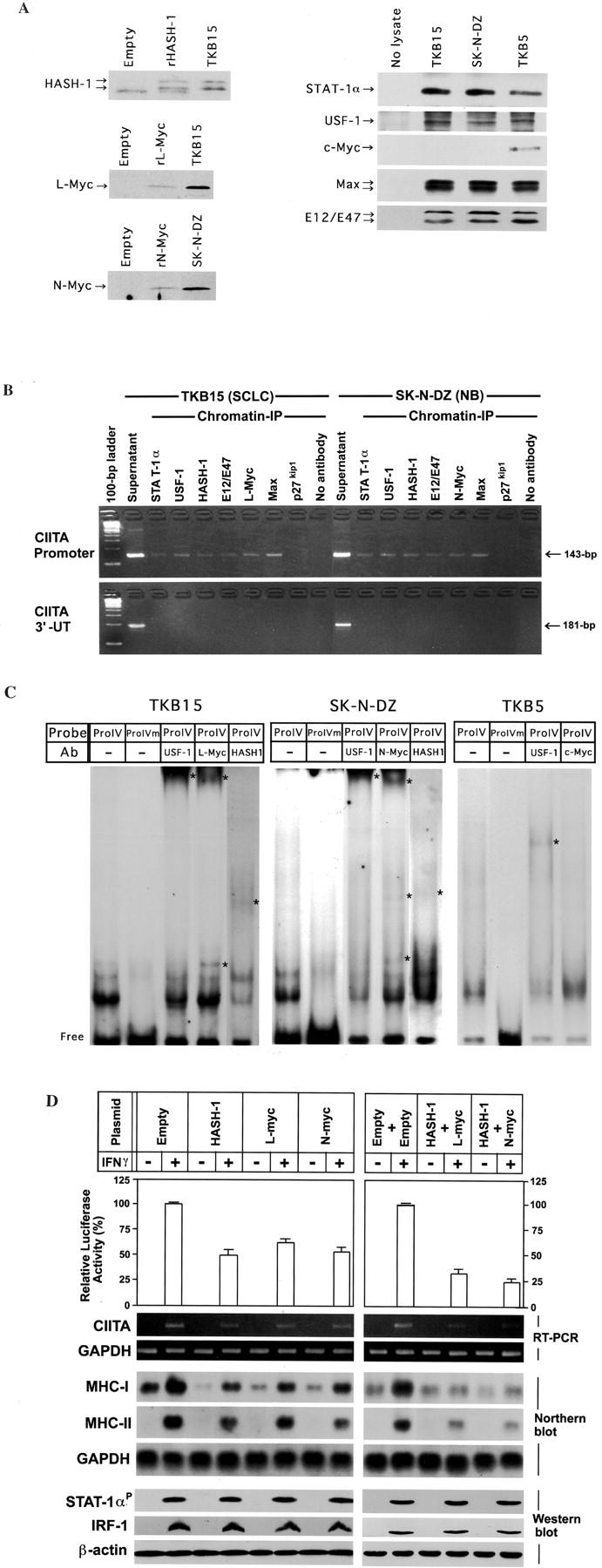

A: Expression vector quality and ability to immunoprecipitate cognate antigen that each antibody (anti-HASH-1, anti-L-Myc, anti-N-Myc, anti-STAT-1α, anti-USF-1, anti-c-Myc, Max, or anti-E12/E47 antibody) recognizes. Immunoprecipitation studies were performed using in vitro transcription and translation reactants from HASH-1-, L-Myc-, or N-Myc-encoding pZeoSV2 vector and nuclear lysate from TKB15, SK-N-DZ, or TKB5. The anti-MASH-1 antibody used in this experiment cross-reacts with recombinant HASH-1 (rHASH-1) and intrinsic HASH-1 protein. The anti-L-Myc antibody reacts with recombinant L-Myc (rL-Myc) and intrinsic L-Myc. The anti-N-Myc antibody reacts with rN-Myc as well as intrinsic N-Myc. Abundant STAT-1α, USF-1, Max, and E12/E47 proteins are immunoprecipitated from both TKB15, SK-N-DZ, and TKB5. The nuclear lysate from TKB5 contains abundant c-Myc protein. These antibodies were used in the chromatin immunoprecipitation assay. Empty: In vitro transcription and translation using a pZeoSV2-empty vector. B: Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay-based PCR using DNA fragments immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibodies. Top: PCR using CIITA promoter IV-specific primers. Bottom: PCR using CIITA 3′-untranslated region (3′-UT)-specific primers. The results show that not only essential transcription factors (STAT-1α and USF-1) but also HASH-1, L-Myc, N-Myc, and their heterodimeric partners (E12/E47 and Max) bind to the E-box in CIITA promoter IV. No primary antibody and p27kip1 antibody: negative control. Sonicated DNA: positive control. Ladder: 100-bp ladder marker. C: Electromobility shift assay using nuclear lysate from TKB15, SK-N-DZ, or TKB5. Although the signals supershifted by the supplement of anti-USF-1 antibody are found both in TKB15, SK-N-DZ, and TKB5, the patterns are different. The signals in TKB15 and SK-N-DZ are also supershifted by the supplement of anti-L-Myc, anti-N-Myc, or anti-HASH-1 antibody. A signal supershifted by the supplement of anti-c-Myc antibody is not isolated in TKB5. ProIV: CIITA promoter IV probe containing IFN-γ-activating site (GAS) and E-box. ProIVm: CIITA promoter IV probe containing GAS and mutated E-box. Ab: Antibody. Asterisk: Supershifted complexes. Free: Free probe. D: Top, Reporter gene assay using TKB5 cells into which neuroendocrine cell-specific bHLH transcription factors were stably transfected, a CIITA promoter IV-encoded luciferase reporter vector, and a control vector. TKB5 was used as a parental cell because it revealed high levels of IFN-γ-inducible CIITA and MHC expression. The reporter and control vectors were transiently co-transfected. Each transient transfectant/co-transfectant is representative of several stable clones. Values of luciferase activity are means + SD of the relative activities in three independent experiments performed in triplicate. The CIITA promoter activity of stably bHLH-transfected TKB5 cell lines is lower than that of the empty vector-transfected one. Co-transfection of HASH-1 with L-myc or N-myc further down-regulates the CIITA promoter IV activity. Bottom: RT-PCR analysis on CIITA mRNA, Northern blot analyses on MHC-I and MHC-II mRNA, and Western blot analyses on phosphorylated STAT-1α, IRF-1, and USF-1 expression in the stable transfectants/co-transfectants. CIITA, MHC-I, and MHC-II mRNA show a decrease on forced expression of HASH-1, L-myc, and N-myc, and these data support those of reporter gene assay. USF-1 is constitutively expressed and IRF-1 (IFN-γ treatment for 24 hours) and phosphorylated STAT-1α (IFN-γ treatment for 30 minutes) are induced well even in HASH-1-, L-myc-, and N-myc-transfectants, or double transfectants.

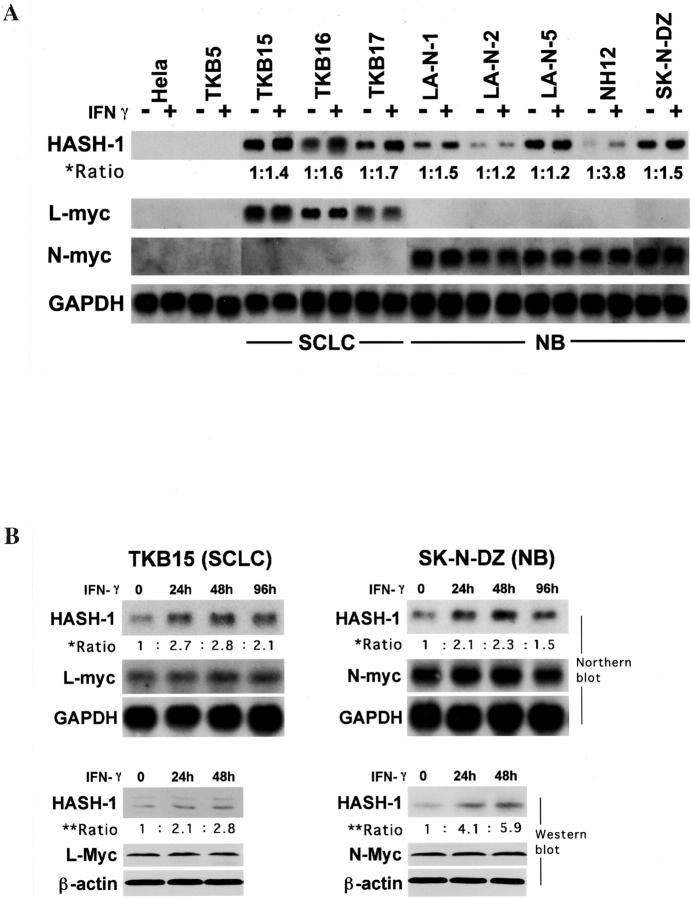

Expression Status of HASH-1, L-myc, and N-myc and Alterations therein after IFN-γ Treatment

As shown in Figure 2A ▶ , the SCLC and NB cell lines constitutively expressed HASH-1 mRNA, mostly at high level, whereas nonneuroendocrine cancer cells did not. These results were consistent with a previous report. 17 The used SCLC cell lines overexpressed L-myc mRNA and the NB cell lines overexpressed N-myc mRNA as in previous studies. 22,23 The c-myc mRNA was undetectable in SCLC and NB cells, detectable in HeLa cells, and overexpressed in TKB5 cells (data not shown). The overexpression of L-myc in SCLCs and N-myc in NBs was associated with marked gene amplification, whereas the HASH-1 gene was not amplified in any SCLC or NB cell line (data not shown). Abundant expression of E12/E47 and Max proteins, heterodimeric partners for HASH-1 and Myc proteins, respectively, was confirmed in SCLC and NB (data partly shown in Figure 3A ▶ ). Furthermore, the HASH-1 expression in SCLC and NB was up-regulated by IFN-γ treatment, whereas the expression levels of L-myc and N-myc were not altered by the treatment (Figure 2A) ▶ . The expression of HASH-1 was transcriptionally and translationally up-regulated until 48 hours after the treatment with IFN-γ (Figure 2B) ▶ .

Figure 2.

A: Northern blot analysis on the expression and alteration by IFN-γ treatment of HASH-1, L-myc, and N-myc. All SCLC and NB cell lines express HASH-1, and IFN-γ treatment up-regulates the HASH-1 expression. The ratio of HASH-1 mRNA expression (asterisk) was calculated as follows: [density of HASH-1 mRNA (IFN-γ(+))/density of GAPDH mRNA (IFN-γ(+))]/[density of HASH-1 mRNA (IFN-γ(−))/density of GAPDH mRNA (IFN-γ(−))]. L-myc is overexpressed in SCLC cell lines and N-myc is overexpressed in NB cell lines, whereas nonneuroendocrine cancers, HeLa and TKB5, do not express HASH-1, L-myc, or N-myc. The expression levels of L-myc and N-myc do not alter with IFN-γ treatment. B: Alteration of HASH-1 mRNA and protein expression in TKB15 (SCLC) and SK-N-DZ (NB) through IFN-γ treatment. The ratio of HASH-1 mRNA level (asterisk) was calculated as follows: [density of HASH-1 mRNA (IFN-γ(+))/density of GAPDH mRNA (IFN-γ(+))]/[density of HASH-1 mRNA (IFN-γ(−))/density of GAPDH mRNA (IFN-γ(−))]. The ratio of HASH-1 protein expression (double asterisk) was calculated as follows: [density of HASH-1 protein (IFN-γ(+))/density of β-actin protein (IFN-γ(+))]/[density of HASH-1 protein (IFN-γ(−))/density of β-actin protein (IFN-γ(−))]. HASH-1 is up-regulated at both the mRNA and protein level by the IFN-γ treatment.

IFN-γ-Inducible CIITA Expression Is Repressed by HASH-1, L-Myc, and N-Myc

As shown in Figure 3A ▶ , the nuclear lysates from TKB15 (SCLC) and SK-N-DZ (NB) contained abundant bHLH transcription factors (USF-1, HASH-1, L-Myc, N-Myc, Max, and E12/E47) and intranuclear (= phosphorylated) STAT-1α and that the nuclear lysate from TKB5 (non-SCLC) contained abundant USF-1, c-Myc, and Max proteins. We next investigated whether the bHLH transcription factors that are specifically overexpressed in SCLC and NB (HASH-1, L-Myc, and N-Myc) modulate CIITA transcription or not. The results of chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments suggested that not only USF-1 but also the other bHLH factors (HASH-1, L-Myc, and N-Myc) bound to the E-box in CIITA promoter IV (Figure 3B) ▶ . The results of electromobility shift assay completely supported the data of chromatin immunoprecipitation assays (Figure 3C) ▶ . In other words, it was confirmed that the bHLH factors specifically overexpressed in neuroendocrine cancers, HASH-1, L-Myc, and N-Myc, could competitively bind to the E-box on CIITA promoter IV with USF-1. It was also clarified that c-Myc did not bind to the E-box in CIITA promoter IV (Figure 3C) ▶ .

Therefore, we further investigated whether these bHLH transcription factors, HASH-1, L-Myc, and N-Myc, actually affect the CIITA transcriptional activity. We transfected the expression vector encoding HASH-1, L-myc, and N-myc into TKB5, which showed well IFN-γ-inducible CIITA and MHC expression as shown in Figure 1A ▶ , and established several clones of stable transfectants expressing each protein and co-transfectants expressing HASH-1 and L-Myc or N-Myc proteins. The IFN-γ signals were confirmed to be transduced well in the cytoplasm and nuclei of transfectants because phosphorylated STAT-1α and IRF-1 were induced by IFN-γ treatment (Figure 3D) ▶ . However, the forced expression of HASH-1, L-Myc, and N-Myc impaired the CIITA promoter IV activity, resulting in a reduction in the IFN-γ induction of CIITA, MHC-I, and MHC-II (Figure 3D) ▶ . The repression was furthermore potentiated through the co-transfection of HASH-1 with L-myc or N-myc (Figure 3D) ▶ .

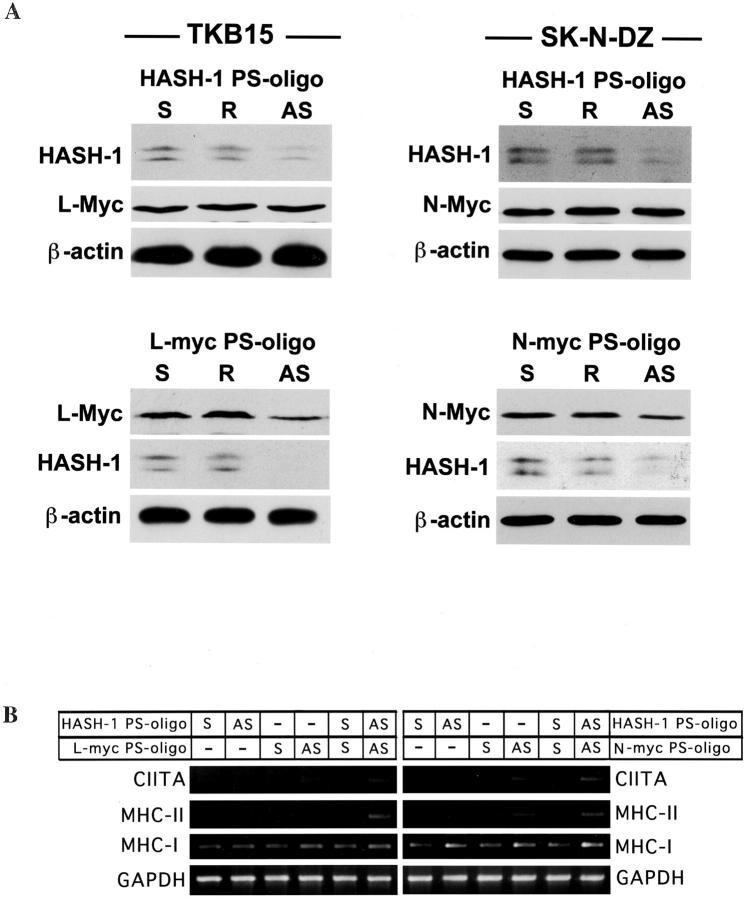

Overexpression of L-myc and N-myc Is Involved in HASH-1 Expression

The anti-sense PS-oligos specific for HASH-1, L-myc, and N-myc maximally reduced the respective mRNA in 12 hours (data not shown) but the reduction of each protein continued for 24 hours (Figure 4A) ▶ . The expression of L-Myc or N-Myc did not alter throughout the anti-sense HASH-1-PS-oligo treatment, whereas the anti-sense L-myc- or N-myc-PS-oligo treatment considerably reduced the expression of HASH-1 (Figure 4A) ▶ . The treatment with the anti-sense L-myc- or N-myc-PS-oligo alone as well as anti-sense HASH-1-PS-oligo alone caused some increase in the IFN-γ-inducible expression of CIITA (Figure 4B) ▶ . And the IFN-γ-inducible expression was further improved through treatment with both anti-sense L-myc- and HASH-1-PS-oligo or both anti-sense N-myc- and HASH-1-PS oligo (Figure 4B) ▶ . These results suggested that the HASH-1-PS-oligo repressed both constitutively expressed and IFN-γ-inducible HASH-1. We summarized these complicated molecular mechanisms leading to the deficiency of IFN-γ-inducible CIITA and MHC expression in neuroendocrine cancers in Figure 5 ▶ .

Figure 4.

The overexpression of L-myc and N-myc is involved in HASH-1 expression. A: Top, Change in the expression of L-Myc and N-Myc proteins associated with forced repression of HASH-1. Bottom: Change in the expression of HASH-1 protein associated with forced repression of L-Myc or N-Myc. Although forced repression of HASH-1 does not influence the expression levels of L-Myc and N-Myc, HASH-1 is down-regulated by the forced repression of L-Myc and N-Myc. S: Sense PS-oligo treatment. R: Reverse PS-oligo treatment. AS: Anti-sense PS-oligo treatment. B: Increase of IFN-γ-inducible CIITA and MHC mRNA expression through forced repression of HASH-1, L-Myc, and N-Myc. The treatment with the anti-sense L-myc- or N-myc-PS-oligo alone as well as anti-sense HASH-1-PS-oligo alone somewhat increases the IFN-γ-inducible expression of CIITA and MHC. The IFN-γ-inducible CIITA and MHC expression are more improved through the double anti-sense PS-oligo treatments (HASH-1 AS + L-Myc AS or HASH-1 AS + N-Myc AS).

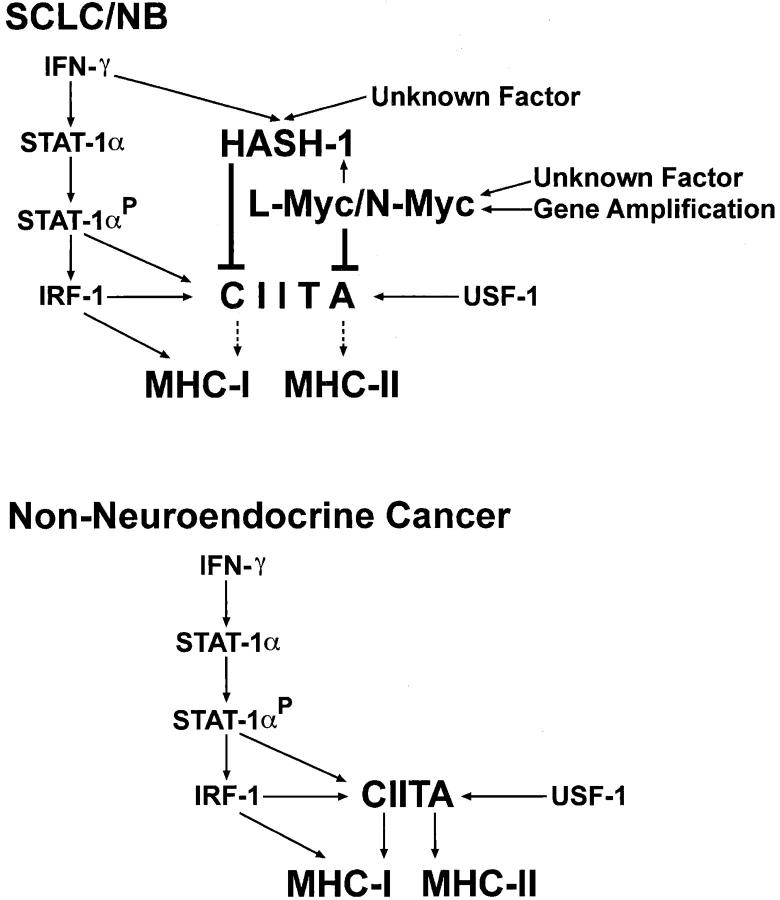

Figure 5.

A scheme for the mechanisms of severe CIITA deficiency in SCLC and NB. In nonneuroendocrine cancers, the CIITA gene is transactivated through the phosphorylated STAT-1α, IRF-1, and USF-1, and this is followed by transactivation of MHC-II and CIITA-mediated MHC-I expression. In addition, the IFN-stimulated response element (ISRE)-mediated MHC-I activation is generated by IRF-1. However, in SCLC and NB, the IFN-γ-inducible CIITA expression is severely repressed by overexpressed HASH-1, L-myc, and N-myc. The IFN-γ treatment up-regulates the HASH-1 expression in SCLC and NB. The overexpressed L-myc and N-myc up-regulates the HASH-1 expression in SCLC and NB.

Discussion

SCLC and NB are both of neuroendocrine origin and represent the most aggressive tumors in adults and infants, respectively. One common histological feature of those tumors is a reduced association with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes that is regarded as a complicated host immune response against cancer cells. It is necessary for the interaction of T cells with cancer cells that both MHC-I and MHC-II are expressed and induced by cytokines such as IFN-γ in cancer cells. 6-9,27,28 We previously clarified that the deficiency of MHC in SCLC was caused by a severe suppression of CIITA. 4 In this study, we have demonstrated that the repression of MHC in NB is also caused by deficient CIITA expression and that neuroendocrine cell-specific bHLH factors competitively bind to the CIITA promoter and repress the promoter IV activity in both NB and SCLC. The expression levels of extrinsic HASH-1, L-myc, and N-myc in TKB5 transfectants were considerably lower than intrinsic levels in SCLC and NB. Therefore, the results of the luciferase assay might have been more conclusive if the expression of extrinsic molecules could have been evoked up to the levels seen in SCLC and NB.

How do bHLH transcription factors specifically expressed in SCLC and NB inhibit the transcription of CIITA? Since Muhlethaler-Mottet and colleagues 16 have described that the close proximity of the GAS and the E-box in CIITA promoter IV is important for activation of the CIITA gene, the three-dimensional interaction between activated STAT-1α, USF-1, and the other transcription factors including the basal transcription factor complex is considered crucial to the IFN-γ-inducible activation of the CIITA gene in epithelial cells. We have clarified here that HASH-1, L-Myc, and N-Myc competitively bind to the E-box in CIITA promoter IV and repress the transcriptional activity (Figure 3 ▶ ; B to D). It has been reported that c-Myc, which is often overexpressed in cancer cells, has a transrepressive function 29 and that the c-Myc/Max/Mad/USF network regulates the binding to E-box. 30 We have also obtained the result that c-Myc does not bind the E-box in CIITA promoter IV (Figure 3C) ▶ as Muhlethaler-Mottet and colleagues 16 have described previously. These results suggest that L-Myc, N-Myc, and HASH-1 apparently differ from c-Myc in both function and the ability to bind to CIITA promoter IV. Furthermore, the pattern supershifted by anti-USF-1 antibody treatment in TKB5 (nonneuroendocrine cancer) was apparently different from those in TKB15 (SCLC) and SK-N-DZ (NB) (Figure 3C) ▶ . This result suggests that the USF-1-containing probe-protein complexes of TKB15 and SK-N-DZ are not identical to those of TKB5. Further study is necessary to fully elucidate the transrepressive mechanisms of CIITA expression involving HASH-1, L-Myc, N-Myc, and the other unknown factors.

There are two pathways for the IFN-γ-inducible transactivation of MHC-I, one mediated by the IFN-stimulated response element (ISRE) and one mediated by CIITA (Figure 5) ▶ . 31 The ISRE is the target DNA-binding site for the IRF family. 31 We have shown here that the IFN-γ stimulation is immediately transduced to responsive factors such as IRF-1 and that a weak induction of MHC-I by IFN-γ is observed even in the SCLC and NB cell lines (Figures 3D and 1A) ▶ ▶ . These results suggest that the IRF-mediated pathway is in effect, whereas the CIITA-mediated MHC-I induction is almost completely deficient in neuroendocrine cancers.

The constitutive expression of MHC-I was also significantly reduced both in SCLC and NB (Figure 1A) ▶ as described previously. 3-5 There have been reports that a silencer 31 or inactivation of an enhancer 32 of the MHC-I gene affects MHC-I repression in NB. However, the forced expression of HASH-1, L-myc, and N-myc also down-regulated the constitutive MHC-I expression in nonneuroendocrine cancer cells (Figure 3D) ▶ . Our results indicate that HASH-1, L-myc, and N-myc also modulate the constitutive expression of MHC-I in SCLC and NB and therefore that various unknown mechanisms act synergistically on MHC-I suppression in SCLC and NB.

Our results suggest that SCLC and NB have complicated mechanisms for the suppression of CIITA. HASH-1 expression is up-regulated by IFN-γ and overexpressed L-myc and N-myc are involved in the expression of HASH-1 in neuroendocrine cancer cells (Figures 2, A and B, and 4A) ▶ ▶ . However, because the TKB5 cells into which L-myc or N-myc was transfected did not express HASH-1 and IFN-γ-treated nonneuroendocrine cancer cells did not express HASH-1 (data not shown), the basal expression of HASH-1 is considered to be regulated by neuroendocrine cell-specific transcription mechanisms. Therefore, further investigation is necessary to clarify the unresolved transcriptional regulatory mechanisms of HASH-1 via neuroendocrine cell-specific bHLH factors and the other factors.

Recent reports have described that forced expression of MHC in cancer cells leads to loss of tumorigenicity. 7,8 Therefore, the overexpression of neuroendocrine cell-specific bHLH factors is associated with a gain of tumorigenicity. It is indispensable for the establishment of an effective anti-tumor immunotherapy including cancer vaccination therapy that both MHC-I and MHC-II are expressed in cancer cells. 6-9,27-34 It is quite reasonable for the protection of the developing neural and neuroendocrine organs from attack by immune competent cells that HASH-1, L-Myc, and N-Myc are co-expressed in immature neuronal and neuroendocrine cells in the fetal period. 19 However, in SCLC and NB, the deregulated expression of bHLH transcription factors might ironically facilitate escape from anti-tumor immunity through severe down-regulation of CIITA and MHC. The overexpressed HASH-1, L-Myc, and N-Myc could not be completely repressed despite treatment with a large amount of PS-oligo (Figure 4A) ▶ as in previous reports. 25,35 These results suggest that it is very hard to establish a PS-oligo therapy against SCLC and NB. However, we have demonstrated here that transfection of the CIITA gene promptly improves MHC expression in SCLC and NB (Figure 1C) ▶ . Because neuroendocrine cancers have been reported to have functions of antigen presentation 36 and antigenicity recognizable by helper and killer T lymphocytes, 9,37 the transfection of the CIITA gene might be essential in establishing an effective immunotherapy against SCLC and NB that have ingenious mechanisms for evading anti-tumor immunity.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Takuya Yazawa, M.D., Yokohama City University School of Medicine, Department of Pathology, 3-9 Fukuura, Kanazawa-Ku, Yokohama, Kanagawa 236-0004, Japan. E-mail: tkyazawa@med.yokohama-cu.ac.jp.

Supported in part by grants-in-aid 11770095 and 11670183 from the Ministry of Education, Sciences, and Culture of Japan.

References

- 1.Travis WD, Colby TV, Corrin B, Shimosato Y, Brambilla E: World Health Organization: Histological Typing of Lung and Pleural Tumours, ed 3 1999:pp 1-156 Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg

- 2.Schwab M, Shimada H, Joshi V, Brodeur GM: Neuroblastic tumours of adrenal gland and sympathetic nervous system. Kleihues P Cabenee WK eds. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Nervous System. 2000:pp 153-161 International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon

- 3.Doyle A, Martin WJ, Funa K, Gazdar A, Carney D, Martin SE, Linnoila I, Cuttitta F, Mulshine J, Bunn P, Minna J: Markedly decreased expression of class I histocompatibility antigens, protein, and mRNA in human small-cell lung cancer. J Exp Med 1985, 161:1135-1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yazawa T, Kamma H, Fujiwara M, Matsui M, Horiguchi H, Satoh H, Fujimoto M, Yokohama K, Ogata T: Lack of class II transactivator causes severe deficiency of HLA-DR expression in small cell lung cancer. J Pathol 1999, 187:191-199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van’t Veer LJ, Beijersbergen RL, Bernards R: N-myc suppress major histocompatibility complex class I gene expression through down-regulation of the p50 subunit of NF-κB. EMBO J 1993, 12:195-200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yun S, Rose ML, Fabre JW: The induction of major histocompatibility complex class II expression is sufficient for the direct activation of human CD4+ T cells by porcine vascular endothelial cells. Transplantation 2000, 69:940-944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostrand-Rosenberg S: Tumor immunotherapy: the tumor cell as an antigen-presenting cell. Curr Opin Immunol 1994, 6:722-726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hock RA, Reynolds BD, Tucker-McClung CL, Kwok WW: Human class II major histocompatibility complex gene transfer into murine neuroblastoma leads to loss of tumorigenicity, immunity against subsequent tumor challenge, and elimination of microscopic preestablished tumors. J Immunother Emphasis Tumor Immunol 1995, 17:12-18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heuer JG, Tucker-McClung C, Gonin R, Hock RA: Retrovirus-mediated gene transfer of B7–1 and MHC class II coverts a poorly immunogenic neuroblastoma into a highly immunogenic one. Hum Gene Ther 1996, 7:2059-2068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamma H, Yazawa T, Ogata T, Horiguchi H, Iijima T: Expression of MHC class II antigens in human lung cancer cells. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol 1991, 60:407-412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujii S, Huang S, Fong TC, Ando D, Burrows F, Jolly DJ, Nemunaitis J, Hoon DS: Induction of melanoma-associated antigen systemic immunity upon intratumoral delivery of interferon-gamma retroviral vector in melanoma patients. Cancer Gene Ther 2000, 7:1220-1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeSandro A, Nagarajan UM, Boss JM: The bare lymphocyte syndrome: molecular clues to the transcriptional regulation of major histocompatibility complex class II genes. Am J Hum Genet 1999, 65:279-286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steimle V, Siegrist CA, Mottet A, Lisowska-Grospierre B, Mach B: Regulation of MHC class II expression by interferon-γ mediated by the transactivator gene CIITA. Science 1994, 265:106-109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin BK, Chin KC, Olsen JC, Skinner CA, Dey A, Ozato K, Ting JP: Induction of MHC class I expression by the MHC class II transactivator CIITA. Immunity 1997, 6:591-600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muhlethaler-Mottet A, Otten LA, Steimle V, Mach B: Expression of MHC class II molecules in different cellular and functional compartments is controlled by different usage of multiple promoters of the transactivator CIITA. EMBO J 1997, 16:2851-2860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muhlethaler-Mottet A, Di Berardino W, Otten LA, Mach B: Activation of the MHC class II transactivator CIITA by interferon-γ requires cooperative interaction between Stat1 and USF-1. Immunity 1998, 8:157-166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ball DW, Azzoli CG, Baylin SB, Chi D, Dou S, Donis-Keller H, Cumaraswamy A, Borges M, Nelkin BD: Identification of a human achaete-scute homolog highly expressed in neuroendocrine tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993, 90:5648-5652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito T, Udaka N, Yazawa T, Okudela K, Hayashi H, Sudo T, Guillemot F, Kageyama R, Kitamura H: Basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors regulate the neuroendocrine differentiation of fetal mouse pulmonary epithelium. Development 2000, 127:3913-3921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kageyama R, Nakanishi S: Helix-loop-helix factors in growth and differentiation of the vertebrate nervous system. Curr Opin Genet Dev 1997, 7:659-665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stanton BR, Perkins AS, Tessarollo L, Sassoon DA, Parada LF: Loss of N-myc function results in embryonic lethality and failure of the epithelial component of the embryo to develop. Genes Dev 1992, 6:2235-2247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zimmerman KA, Yancopoulos GD, Collum RG, Smith RK, Kohl NE, Denis KA, Nau MM, Witte ON, Toran-Allerand D, Gee CE, Minna JD, Frederick WA: Differential expression of myc family genes during murine development. Nature 1986, 319:780-783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Littlewood TD, Evan GI: Sheterline P eds. Helix-Loop-Helix Transcription Factors, ed 3 1998:pp 1-151 Oxford University Press, New York

- 23.Nesbit CE, Tersak JM, Prochownik EV: MYC oncogenes and human neoplastic disease. Oncogene 1999, 18:3004-3016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nozaki N, Naoe T, Okazaki T: Immunoaffinity purification and characterization of CACGTG sequence-binding proteins from cultured mammalian cells using an anti-c-Myc monoclonal antibody recognizing the DNA-binding domain. J Biochem 1997, 121:550-559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moreno CS, Beresford GW, Louis-Plence P, Morris AC, Boss JM: CREB regulates MHC class II expression in a CIITA-dependent manner. Immunity 1999, 10:143-151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galderisi U, Di Bernardo G, Cipollaro M, Peluso G, Cascino A, Cotrufo R, Melone MA: Differentiation and apoptosis of neuroblastoma cells: role of N-myc gene product. J Cell Biochem 1999, 73:97-105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baskar S, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Nabavi N, Nadler LM, Freeman GJ, Glimcher LH: Constitutive expression of B7 restores immunogenicity of tumor cells expressing truncated major histocompatibility complex class II molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993, 90:5687-5690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin BK, Frelinger JG, Ting JP: Combination gene therapy with CD86 and the MHC class II transactivator in the control of lung tumor growth. J Immunol 1999, 162:6663-6670 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin-Heng L, Nerlov C, Prendergast G, MacGregor D, Ziff EB: c-Myc represses transcription in vivo by a novel mechanism dependent on the initiator element and Myc box II. EMBO J 1994, 13:4070-4079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sommer A, Bousset K, Kremmer E, Austen M, Luscher B: Identification and characterization of specific DNA-binding complexes containing members of the Myc/Max/Mad network of transcriptional regulators. EMBO J 1998, 13:4080-4086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gobin SJP, Peijnenburg A, Keijsers V, van den Elsen PJ: Site α is crucial for two routes of IFNγ-induced MHC class I transactivation: the ISRE-mediated route and a novel pathway involving CIITA. Immunity 1997, 6:601-611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy C, Nikodem D, Howcroft K, Weissman JD, Singer DS: Active repression of major histocompatibility complex class I gene in a human neuroblastoma cell line. J Biol Chem 1996, 271:30992-30999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lenardo M, Rustigi AK, Schievella AR, Bernards R: Suppression of MHC class I gene expression by N-myc through enhancer inactivation. EMBO J 1989, 8:3351-3355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melief CJM, Offringa R, Toes REM, Kast WM: Peptide-based cancer vaccines. Curr Opin Immunol 1996, 8:651-657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dosaka-Akita H, Akie K, Hiroumi H, Kinoshita I, Kawakami Y, Murakami A: Inhibition of proliferation by L-myc antisense DNA for the transcriptional initiation site in human small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res 1995, 55:1559-1564 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spierings DCJ, Agsteribbe E, Wilschut J, Huchriede A: Characterization of antigen-presenting properties of tumour cells using virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Br J Cancer 2000, 82:1474-1479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamazaki K, Spruill G, Rhoderick J, Spielman J, Savaraj N, Podack ER: Small cell lung carcinomas express shared and private tumor antigens presented by HLA-A1 or HLA-A2. Cancer Res 1999, 59:4652-4650 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]