Abstract

Global genome amplification from formalin-fixed tissues is still problematic when performed with low cell numbers. Here, we tested a recently developed method for whole genome amplification termed “SCOMP” (single cell comparative genomic hybridization) on archival tissues of different ages. We show that the method is very well suited for formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples obtained by nuclei extraction or laser microdissection. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products can be used for subsequent comparative genomic hybridization, loss of heterozygosity studies, and DNA sequencing. To control for PCR-induced artifacts we amplified genomic DNA isolated from 20 nuclei of archival formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded nonpathological lymph nodes. Subsequent comparative genomic hybridization revealed the expected balanced profiles. For loss of heterozygosity analysis by microsatellite PCR 60 to 160 cells were sufficient. In comparative experiments the approach turned out to be superior to published degenerated oligonucleotide-primed-PCR protocols. The method provides a robust and valuable tool to study very small cell samples, such as the genomes of dysplastic cells or the clonal evolution within heterogeneous tumors.

Pathological processes are frequently identified by the morphological analysis of diseased tissues. Up to date, formalin fixation and subsequent paraffin embedding provides the best preservation of tissue and cell morphology and is therefore routinely used in clinical histopathology. In current pathological research the molecular genetic characterization of conspicuously changed tissues has become an absolute requirement. Here, it is important to separate genetically aberrant from surrounding normal cells, which can be elegantly achieved by laser microdissection when small and locally restricted pathological processes are to be studied. 1,2 However, the genetic analysis of tissues obtained by microdissection is often limited when insufficient amounts of DNA are extracted.

As a consequence, numerous protocols have been developed for the analysis of minute amounts of DNA from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues. A challenging task is to comprehensively amplify the genomic DNA, and not only specific DNA sequences, enabling the subsequent application of various molecular genetic techniques. However, global genome amplification is particularly demanding because tissue preservation by formalin fixation and paraffin embedding negatively influences polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification. At present, degenerated oligonucleotide-primed-PCR (DOP-PCR) 3 and primer extension preamplification 4 are commonly used to perform whole genome amplification from formalin-fixed tissues. DOP-PCR rests on the use of partially degenerated primers and low stringent PCR conditions whereas primer extension preamplification uses completely degenerated primers, and consequently both methods are based on the use of thousands to millions of different primers. Each protocol has been frequently modified 5-13 to various extents suggesting the existence of inherent principal problems that cannot be overcome by the modification of one or several parameters.

Recently, we introduced a novel method for whole genome amplification. 14 The comprehensive amplification of genomic DNA and its sensitivity was demonstrated by the successful application of PCR products that were obtained from DNA of a single cell for comparative genomic hybridization (CGH), loss of heterozygosity studies, and DNA sequencing. Because the amplification protocol allowed single cell CGH, the method was termed SCOMP. In contrast to the DOP and primer extension preamplification techniques, only a single primer is needed, binding to a sequence that has been ligated to DNA fragments, which resulted from complete genomic digestion with the restriction enzyme MseI.

Having a method in hand for freshly prepared samples, we tested SCOMP here for the amplification of DNA isolated from archival formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues. We show that SCOMP can be applied to minute amounts of DNA from such samples and that it is superior to DOP-PCR. In addition, we investigated factors that influence the amplification success.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Samples

Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded clinical samples were obtained from the pathology departments of the University of Hamburg (center A), of the city hospital of Augsburg (center B), and of the University of Munich (center C), Germany. All investigated tumor tissues (Table 1) ▶ were randomly selected from the archives of the three different centers.

Table 1.

Formalin-Fixed and Paraffin-Embedded Tissues from Three Different Pathology Departments Investigated with SCOMP

| Samples from center | Cell number | Area size‡ | PCR results§ | Successful CGH | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | |||||

| Normal tissue | |||||||

| <4 years | 1 | 4 | 20, 60, 160 | 2, 8, 48 | 15/15 | 12/12 | |

| >4 years | 1 | 2 | 20, 60, 160 | 2, 8, 48 | 9/9 | 6/6 | |

| Tumor tissue* | |||||||

| <4 years | 6 | 5 | 1 | 20–100‡ | 8–50 | 13/13 | 8/8 |

| 5 | 13 | 100–800‡ | 50–100 | 18/18 | 14/15 | ||

| >4 years | 5 | 2 | 20–100‡ | 8–50 | 6/7 | 4/4 | |

| 7 | 100–800‡ | 50–100 | 5/7 | 2/2 | |||

;*Esophageal cancer, breast cancer, and colon cancer.

†Approximate number.

‡Number × 1000 μ2.

§Successful control PCR for microsatellite marker D5S500 or D17S800.

Micromanipulation

Groups of three unstained cells that had been fixed in 4% buffered formalin for 20 and 40 hours, were aspirated into a glass pipette of 30-μm diameter and were transferred to a new slide. After confirming that only three cells had been transferred, these cells were finally picked in 1 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/0.5% Igepal (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) into the PCR reaction tube.

Tissue Processing

For controlled quantitative experimental conditions we isolated nuclei from tissue blocks of different ages from three nonpathological formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded lymph nodes according to the protocol of Hyytinen and colleagues. 15 After a washing step in PBS the nuclei were resuspended in PBS/0.5% Igepal and were diluted to a final concentration of 20 nuclei/μl, 60 nuclei/μl, and 160 nuclei/μl.

Laser Microdissection

Sequential 5-μm sections were cut from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue blocks using a microtome with a disposable blade. For morphological control, one slide was stained with conventional hematoxylin and eosin staining and the sequential section was prepared for laser microdissection and mounted onto a 1.35-μm-thin polyethylene membrane (P.A.L.M. Microlaser Technologies, Bernried, Germany), attached to a glass slide. For microdissection the tissue sections were deparaffinized on a shaker, changing the xylene twice, and then incubated for 30 minutes each and were then subsequently rehydrated with a series of 100%, 85%, and 70% ethanol. To avoid interference of the nuclear staining with the amplification, slides were stained in diluted (50%) hematoxylin (Gill’s, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 5 minutes. The staining was followed by a dehydrating ethanol series and the slides were dried overnight in the presence of a desiccant. For microdissection we used the P.A.L.M. Laser-Microbeam system (P.A.L.M. Microlaser Technologies). The inner side of a 200-μl tube cap was covered with 3 to 5 μl of PCR oil and the isolated cells were catapulted into the cap. The cap was subsequently mounted onto the tube and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 5 minutes. Then 3 μl of lysis buffer [10 mmol/L Tris-acetate, pH 7.5, 10 mmol/L Mg-acetate, 50 mmol/L K-acetate (0.2 μl of 10× Pharmacia One-Phor-All-Buffer-Plus), 0.67% Tween 20 (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany), 0.67% Igepal (Sigma), and 1.3 mg/ml proteinase K] were added to the tube and centrifuged again for 14,000 × g for 5 minutes to separate the reaction mix from the oil.

SCOMP

After inactivation of proteinase K at 80°C for 10 minutes SCOMP was performed as described previously by Klein and colleagues 14 with the exception of the adaptor-oligonucleotides (Lib1-primer: 5′-AGT GGG ATT CCT GCT GTC AGT-3′; ddMse-primer: 5′-TAA CTG ACA GCdd-3′).

Probe Labeling and CGH

The labeling reaction was performed in a total volume of 40 μl consisting of 4 μl of 10× PCR buffer (Expand Long Template PCR System, Buffer 1; Roche, Mannheim, Germany), 6 μl of Lib1-primer (10 μmol/L), 1.4 μl of a dNTP stock solution (10 mmol/L for dATP, dCTP, and dGTP; 8.75 mmol/L for dTTP), 1.75 μl of 1 mmol/L digoxigenin-11-dUTP (Roche) for the test-DNA or 1.75 μl of 1 mmol/L biotin-16-dUTP (Roche) for the reference DNA, respectively, and 2.5 U of Taq-polymerase (Roche). We used 1.25 μl of the SCOMP product for reamplification and a MJ-Research PTC-200 thermocycler (Waltham, MA) was programmed to 94°C (1 minute), 60°C (30 seconds), 72°C (2 minutes) for one cycle; 94°C (30 seconds), 60°C (30 seconds), 72°C (2 minutes plus 20 seconds/cycle) for 10 cycles. The labeled products were used for CGH as described. 14 Quantitative evaluation of the ratio of test and control DNA was done according to du Manoir and colleagues 16 by using the Leica (Bensheim, Germany) software package Q-CGH. Five to 12 metaphases were evaluated in each experiment.

DOP-PCR

For DOP-PCR, microdissection and proteinase K digestion were performed under identical conditions as described above. After inactivation of proteinase K at 80°C for 10 minutes we used the protocol described by Speicher and colleagues 5 for the primary DOP-PCR in a final volume of 50 μl. The primary DOP-PCR product was labeled in a second amplification step for 35 cycles under high stringency conditions of the DOP-PCR protocol mentioned above.

Sequence-Specific PCR

The PCRs for specific sequences and for microsatellite analysis were performed using 1.25 μl from the preamplified DNA in a final volume of 10 μl [10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 50 mmol/L KCl, 1 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.1 mmol/L dNTP, 0.4 μmol/L each primer, 0.25 μl bovine serum albumin (20 mg/ml), and 0.5 U Taq polymerase]. The PCR reaction was run in a MJ-Research PTC-200 thermocycler programmed to 94°C (2 minutes), 58°C (30 seconds), 72°C (2 minutes) for one cycle, 94°C (15 seconds), 58°C (30 seconds), 72°C (20 seconds) for 14 cycles, 94°C (15 seconds), 58°C (30 seconds), 72°C (30 seconds), and a final extension at 72°C for 2 minutes. The results were visualized by SYBR Green (Biozym, Oldendorf, Germany)-stained 7% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using a Fluorimager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). Gel conditions were as described by Litt and colleagues 17 The primer sequences for the test of complete MseI digestion were 5′-TCC CAG TGA CAG ATG TGA G-3′ and 5′-CTT CCG GTA CAG CCT GTG-3′ and are located on chromosome 17p13.3. The primer sequences used for microsatellite analysis are provided in Table 2 ▶ .

Table 2.

Primers Used for the Loss of Heterozygosity Analysis of Selected Markers Shown in Figure 5 ▶

| STS marker | 5′-Primer | 3′-Primer |

|---|---|---|

| D5S500 | 5′-CACCTATTCGACCTAATGAC-3′ | 5′-TGAAGTCCTCTCCAACGTG-3′ |

| D16S485 | 5′-AGTAATAATGTACCTGGTAAC-3′ | 5′-AGGCAATTTGTTACAGAGCC-3′ |

| D16S3040 | 5′-CTGCAACAAGAAAGATACTCC-3′ | 5′-AGTGCCTCACAGGCTGCC-3′ |

| D5S816 | 5′-TTGCCACTGAAAATCATATCC-3′ | 5′-CAGTGTCCCAGACTCAGAC-3′ |

| D17S1161 | 5′-CAGTTAGCCAAGATAATGCC-3′ | 5′-CTCATAAGGGGATAAAGGAC-3′ |

| D17S800 | 5′-CTTATGGTCTCATCCATCAGG-3′ | 5′-GACAGAAAGATGGATAAGACAAG-3′ |

| D5S592 | 5′-GTCAACAAAGTAATGTAAAGACAG-3′ | 5′-TGGAGTGGAGAGCTGCTCAG-3′ |

| D5S471 | 5′-GTTTTCACACATTTTCCCAGC-3′ | 5′-GTTACAACAAATAGCAACAGC-3′ |

| D3S3624 | 5′-CCAGTGGGATATGACTGCC-3′ | 5′-CTTACTACTGTTACTTCAGCC-3′ |

| D3S3721 | 5′-GAAACCTCCTGACCATCCTG-3′ | 5′-GGCAAATACAAGTCCCAGGG-3′ |

| D3S1210 | 5′-GGCTATTTTGCAACTTACTCG-3′ | 5′-GGCAATATGAAATGAAATACAGG-3′ |

| D5S1360 | 5′-ACAAACAAAACCAAGAGTGC-3′ | 5′-TGGCTCATGTATCCCTATGT-3′ |

| D16S3095 | 5′-TCAGTTGGAAGATGAGTTGG-3′ | 5′-TATAGTTTGTGTCCCCCGAC-3′ |

| D16S3138 | 5′-GATTACAGGCATGAGCCACTG-3′ | 5′-TTAGAAATGTCTGCATGTATGAG-3′ |

| D16S3066 | 5′-GCTGTTAATATGAAACAATTGCC-3′ | 5′-GGGGTCTAATGGTTCAGCC-3′ |

| D16S3019 | 5′-CAACTCATTCCCTGTGTGAC-3′ | 5′-AACCAAGTGGGTTAGGTCAG-3′ |

| D5S615 | 5′-GGTAAACCCTCAAGCAGTC-3′ | 5′-AACCAGTTTCTTATTATAAGCC-3′ |

| D5S2117 | 5′-CCAGGTGAGAACCTAGTCAG-3′ | 5′-ACTGAGTCCTCCAACCATGG-3′ |

Results

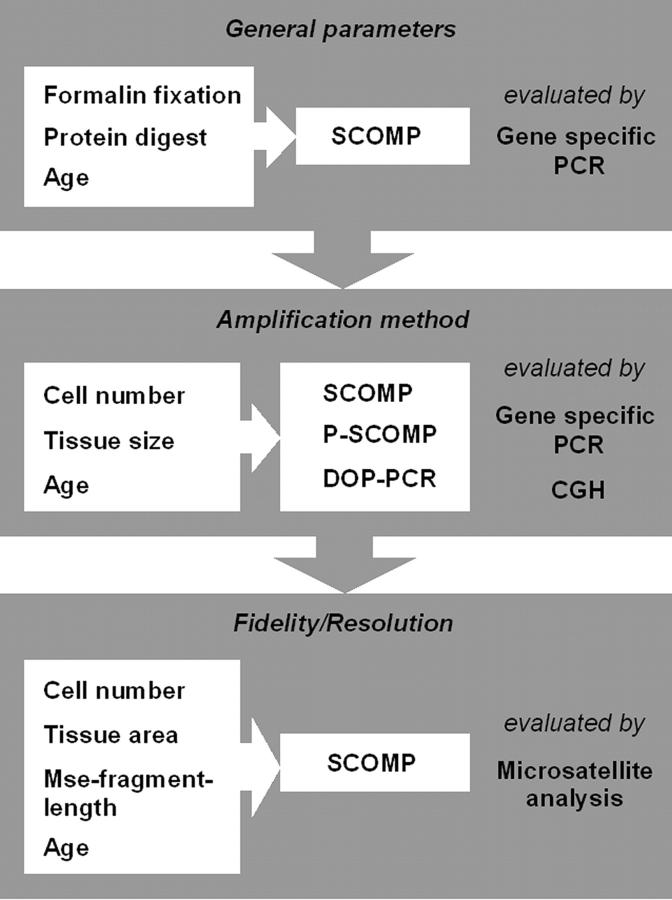

In a series of experiments we tested the applicability of SCOMP for comprehensive genomic amplification of microdissected material from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues (Figure 1) ▶ . Because our method relies on the ligation of preformed adaptors to double-stranded MseI-restricted genomic fragments, DNA quality and DNA preparation is of particular importance. Therefore, we started to investigate the influence of formalin fixation, of sample age, and of DNA extraction on the amplification success.

Figure 1.

Synopsis of the experimental design to evaluate SCOMP for formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues. The box on the left lists factors that potentially influence whole genome amplification (WGA) by the applied protocol (middle) and the box on the right indicates how WGA was evaluated.

General Factors for Successful Amplification

In the first step, we assessed the minimal amount of DNA extracted from formalin-fixed tissue that is needed for successful whole genome amplification. Freshly isolated peripheral blood lymphocytes were fixed with 4% buffered formalin for 20 hours and 40 hours, because the incubation time for routine samples is not standardized but within this range. Groups of three cells were isolated by micromanipulation and subsequently subjected to the SCOMP protocol. Results were comparable to unfixed cells as tested by gene-specific PCR, in particular no difference was observed between 20 and 40 hours of formalin incubation. This indicates that the formalin fixation alone does not significantly interfere with the protocol (data not shown).

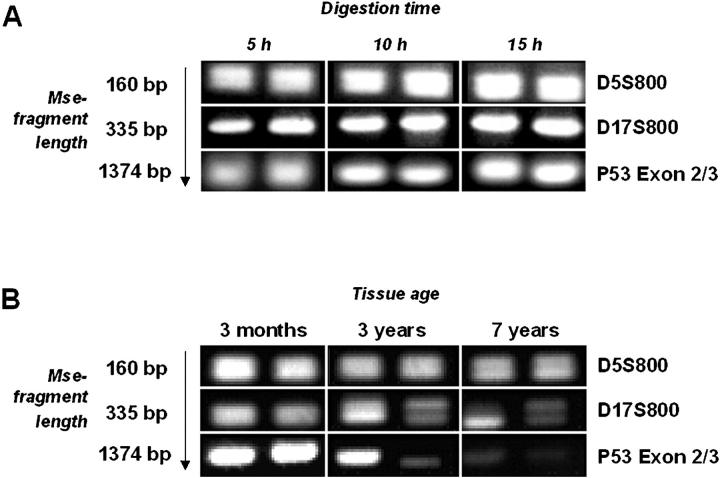

High proteinase concentrations and a long digestion time are known to be critical for high DNA yield from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues. 5 To test the effect of proteinase K incubation time before SCOMP, laser-microdissected tissue comprising an area of 48,000 μm2 (equivalent to six circles with a diameter of 100 μm each) was obtained from a 5-μm tissue section of a nonpathological lymph node that had been resected and fixed 1 month before. The samples were independently digested using 1.3 mg/ml of proteinase K for 5, 10, and 15 hours. Then we applied the SCOMP protocol and successful amplification was tested with primers for microsatellite markers located on selected MseI fragments. Because we expected longer MseI fragments to be more critical on amplification, we used primers that bind to sequences on MseI fragments of 160, 335, and 1374 bp in length. As shown in Figure 2A ▶ , no clear difference could be observed between 5, 10, and 15 hours of digestion for the tested specific sequences. However, because the incubation time of 15 hours seemed to result in the brightest PCR bands (Figure 2A) ▶ , this proteinase K digestion time was chosen for the subsequent experiments.

Figure 2.

Influence of proteinase K digestion time and sample age on sequence-specific PCRs. The microsatellite markers D5S500, D17S800, and the P53 exon 2/3 located on MseI-fragments of 160 bp, 335 bp, and 1374 bp in length, respectively, were used to analyze the amplification efficiency of SCOMP on material from nonpathological lymph nodes. Influence of different proteinase K digestion times (A) and of sample age (B).

We then investigated the influence of sample age on SCOMP efficiency and used DNA derived from nonpathological formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded lymph nodes. Two independently prepared nucleic suspensions of 180 nuclei each from tissue blocks of different ages, ie, 3 months, 3 years, and 7 years, were tested. The same microsatellite markers as before served to determine the effect of sample age on global amplification. Here, we observed a clear reduction of amplification efficiency for the longest of the three MseI fragments with increasing age. As shown in Figure 2B ▶ the 1374-bp fragment was not as good amplified from the 3-year-old and older samples as from the 3-month-old sample.

Because formalin-fixed DNA may be resistant to MseI restriction, thereby impeding efficient amplification, we tested whether we could detect incomplete restriction digest. For this purpose we tried to amplify a genomic sequence (318 bp) containing a MseI restriction site between the two sequence-specific primers. It was not possible to amplify the selected sequence from different amounts of formalin-fixed, MseI-restricted DNA in contrast to undigested control DNA (data not shown). Therefore, incomplete MseI digestion does not commonly occur under the applied conditions.

Amplification Method

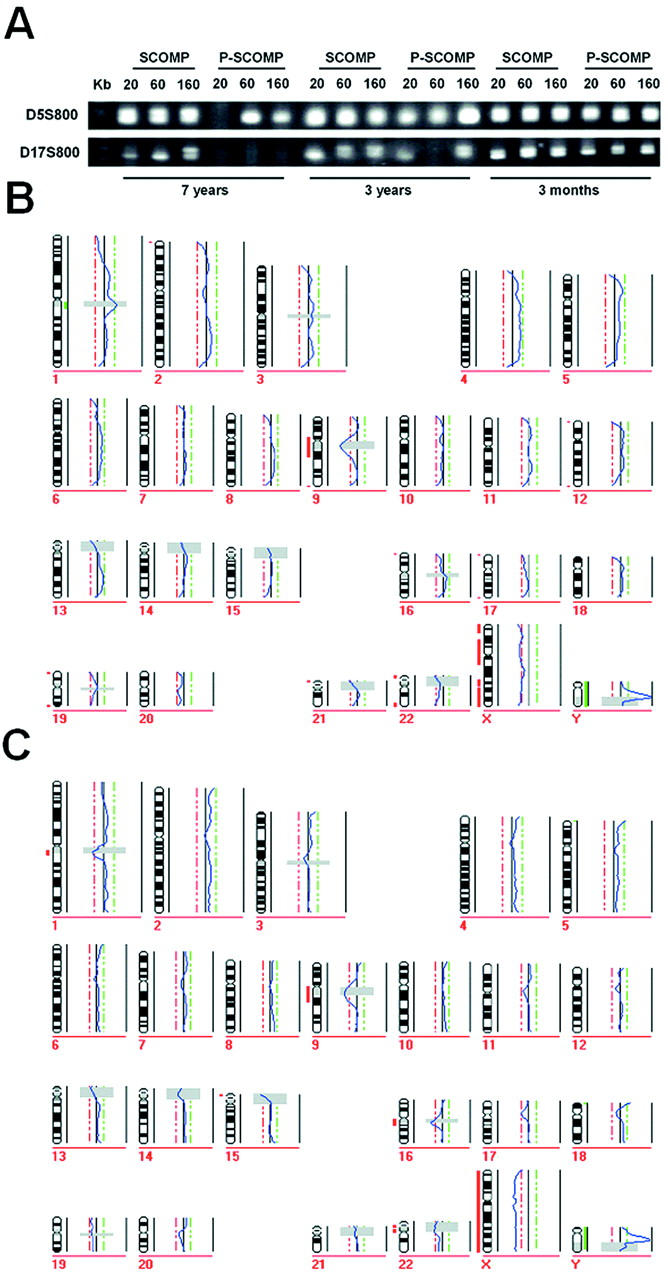

DNA from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue can be substantially degraded. 18,19 Therefore, extensive genomic fragmentation can result in short DNA sequences that contain only one or no MseI restriction site and consequently those sequences would not be amplified by SCOMP. To rescue such DNA fragments we tested whether polishing of the overhanging DNA ends combined with blunt-end ligation of the adaptors would improve the genome amplification. This approach, here called P-SCOMP (“P” standing for polished), was compared with the standard SCOMP. The protocol used to polish the DNA ends and ligate adaptors worked well for DNA fragmented with restriction enzymes that produce 5′-protruding and -recessive ends, naturally degraded DNA from archival tissues was less efficiently amplified than that amplified by standard SCOMP (Figure 3A ▶ and data not shown). Remarkably, SCOMP allowed the amplification of DNA from only 20 nuclei of the 7-year-old lymph node sample (Figure 3A) ▶ .

Figure 3.

Comparison of SCOMP and P-SCOMP. A: Microsatellite markers D5S500 and D17S800 were used to test SCOMP products from nucleic suspensions with 20, 60, and 160 nuclei. B: CGH profile generated from 20 nuclei of the nonpathological 7-year-old lymph node tissue block and CGH profile of the 3-month-old sample (C).

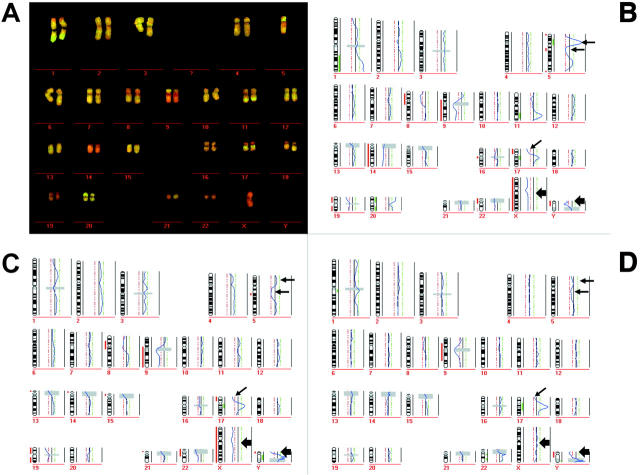

To validate this finding for the entire genome, the SCOMP products were then subjected to CGH. The amplified DNA was labeled and co-hybridized with differently labeled normal placenta DNA to human metaphase spreads that were prepared from normal lymphocyte cultures. Although all labeled SCOMP probes showed smooth, high-intensity hybridizations with low granularity, we noticed that the hybridization intensity of the 3-month-old specimen was higher than the one obtained from the 7-year-old sample. In addition, the signal intensities of the labeled PCR products obtained from 20 cells were slightly lower than those obtained from 160 cells. Nevertheless, all SCOMP samples displayed adequate signal-to-background ratios. The CGH profiles of the cells, even those that were isolated from the 7-year-old nonpathological lymph node sample, did not display any PCR-related chromosomal gains or losses (Figure 3B) ▶ . In addition the male sex of the donors of the test DNA was clearly identified (Figure 3B) ▶ .

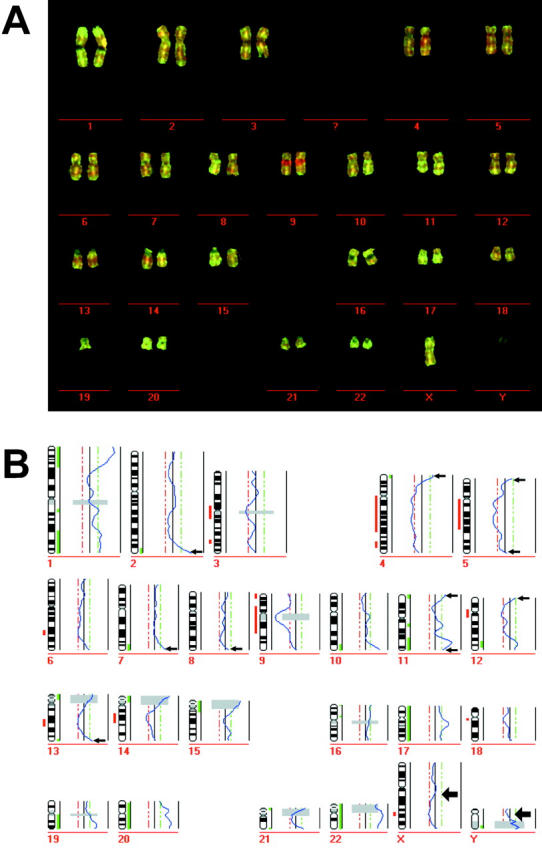

Having demonstrated the suitability of SCOMP to amplify DNA that was isolated from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues, we compared the SCOMP protocol with the most frequently applied method, the DOP-PCR. We applied DOP-PCR first to DNA that was isolated from more than 5000 cells. The obtained DOP-PCR probes hybridized well to the metaphase spreads. Then, we compared the efficiency of the DOP-PCR with SCOMP on minute, laser-microdissected tissue samples. Using DNA from 8000 μm2 no adequate hybridization signal could be obtained using DOP-PCR, which was easily achieved by SCOMP (see below). The high signal-to-noise ratio and an extensive granular hybridization of the DOP-PCR products (Figure 4A) ▶ were incompatible with the standard settings of the evaluation software. 16 In addition, the obtained CGH profile displayed the typical artifacts that are often seen when CGH with DOP-PCR products is performed, ie, excessive telomeric amplifications or losses. Finally, the failure to retrieve the correct sex of the donor underlines the insufficient sensitivity of DOP-PCR, because no significant deviation from the midline was observed although we mismatched the sex of the control DNA (Figure 4B) ▶ .

Figure 4.

CGH using DOP-amplified DNA. A: Exemplary CGH karyogram of a DOP-PCR experiment with DNA extracted from an area of 8000 μm2 of an esophageal adenocarcinoma. B: Profile calculated from nine metaphases of the DOP-PCR amplification.

Fidelity/Resolution

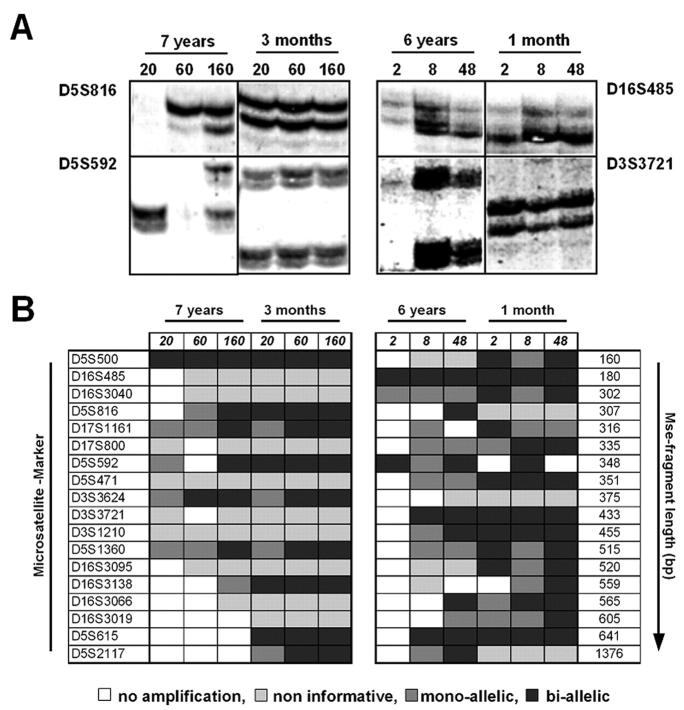

Although the CGH experiments (as well as sequence-specific PCRs; not shown) proved that SCOMP is superior to DOP-PCR for the amplification of genomic DNA of less than 200 cells from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues we proceeded to determine its reliability on a single copy sequence level. Therefore, we conducted loss of heterozygosity experiments using 18 microsatellite markers mapping to four different chromosomal regions (3p13 to 3p21, 5q23 to 5q31, 16q22 to 16q23, and 17q21 to 17q22). All 18 specific PCRs were performed with the SCOMP primary PCR products. To perform these analyses we used the same DNA that we had extracted for the experiments shown in Figure 3 ▶ (ie, different cell numbers of nuclei suspension derived from normal lymph nodes of different ages). Because the selected PCR primers amplify highly polymorphic sequences, the resulting products were analyzed on a sequencing gel to discriminate between the maternal and the paternal allele. Each sequence-specific PCR can result in one of four different outcomes: 1) no amplification at all; 2) a single band is amplified in all samples of an individual patient (ie, maternal and paternal allele cannot be differentiated, the patient is noninformative for the respective marker); 3) the patient is informative, however one allele is artificially lost during PCR (mono-allelic amplification); 4) the patient is informative for the specific marker and both alleles are successfully amplified (bi-allelic amplification). Because we had noted before (Figure 2B) ▶ that the length of the MseI fragment as well as the age of the sample influence the amplification success, the products, run on an acrylamide gel (Figure 5A ▶ , left), were evaluated for these two factors.

Figure 5.

Loss of heterozygosity analysis of selected markers. A and B: Isolated nuclei (left) or microdissected tissue samples (right) were amplified by SCOMP, which was followed by locus-specific PCR. A: Example of polyacrylamide gel of informative markers for isolated nuclei (D5S500 and D5S592) and microdissected tissue (D16S485 and D3S3721). B: Results of all microsatellite markers. Markers are listed with increasing MseI fragment length. Numbers at left indicate the total number of isolated nuclei, from which DNA was extracted, whereas numbers at the right represent the area of the microdissected tissue (2, 2000 μm2; 8, 8000 μm2; 48, 48,000 μm2).

As expected, results clearly depended on cell number and sample age: the younger the material and the shorter the MseI fragment that had to be amplified during primary PCR, the more alleles could be detected (Figure 5B ▶ , left). From freshly fixed tissue 60 nuclei were sufficient for reliable amplification of a single copy sequence, regardless of fragment length. In contrast, when 7-year-old archival tissue was studied, 160 cells were needed to obtain similar results. The length of the analyzed polymorphic, MseI-restricted sequence becomes more important with increasing age of the tissue. In comparison to the younger sample, MseI fragments smaller than 400 bp could be detected in 93% in the 7-year-old sample, whereas sequences larger than 400 bp could be amplified in only 44% (Figure 6B) ▶ . This finding was statistically significant (chi-square, P < 0.001).

Figure 6.

CGH using SCOMP-amplified DNA. The DNA for SCOMP amplification was isolated from the identical slide as the DNA for the DOP experiment. A and B: Karyogram from a microdissected area with a size of 8000 μm2 and the resulting ratio profile (B). CGH profiles in C and D were derived from DNA isolated from 40,000 μm2 and from ∼5 × 105 cells, respectively. Arrows point to the aberrations, which became more defined in the smaller samples. Note the significant profile deviation from the midline at the X-chromosome because of the mismatched sex in B and C (bold arrows). In D we hybridized sex-matched probes (balanced profile at the X-chromosome).

Similar results were obtained using microdissected fragments from two nonpathological lymph nodes (Figure 5A ▶ , right). Here, we microdissected defined circles with an area of 2000 μm2, 8000 μm2, and 48,000 μm2, respectively. As shown in Figure 5B ▶ , right panel, specific amplification of the polymorphic sites was clearly better in the younger sample, for shorter fragments and with increasing size of the microdissected areas.

Analysis of Pathological Samples

Having demonstrated the efficiency of the SCOMP protocol using genomically normal cells, we investigated laser-microdissected material from an esophageal cancer. We used a 5-year-old paraffin block of an esophageal adenocarcinoma, of which DOP-amplified DNA extracted from less than 2000 cells had not been successfully hybridized (Figure 4) ▶ . A cell line of this primary tumor (PT1590) had previously been characterized by M-FISH. 20 In addition, we could compare our results with the CGH data of the cell line PT1590 that was established from the primary tumor (Jürgen Kraus, Michael Speicher, personal communication). The smallest size of the microdissected area was set to 8000 μm2, because the amount of DNA extracted from this size had resulted in an acceptable amplification for single copy sequences in the case of the 6-year-old lymph node sample (Figure 5) ▶ . In addition, DNA was isolated from 40,000 μm2 and from ∼100,000 cells. In the investigated tumor sample 8000 μm2 corresponded to ∼30 cells. Because primary tumors can be very heterogeneous and, in addition, are contaminated to various degrees by stromal or infiltrating cells, we expected similar, but not necessarily identical results between the different microdissected areas.

All chromosomal aberrations present in the cell line were also detected after SCOMP amplification of all microdissected areas. In particular, the data concurred in the finding of deletions at 5q, 8p, 17p, 19p, loss of the Y-chromosome, and the amplification at 17q. However, we were surprised by the extent of higher sensitivity and resolution obtained with smaller cell numbers. As can be seen from Figure 6, B and C ▶ , chromosomal gains and losses for several loci became more pronounced and defined using small microdissected areas than using DNA from large tumor cell numbers (Figure 6D) ▶ . For example, loss of the short arm of chromosome 17 was increasingly visible the more defined areas were used and the high-copy amplifications on 5p12-14 and 11q22-24 was only detectable in the 8000 μm2 sample.

To test whether SCOMP had been only sporadically successful using the nine samples reported, we analyzed 43 additional tumor samples. These samples were derived from three different departments of pathology (University of Hamburg, center A; city hospital Augsburg, center B; University of Munich, center C) and had been stored for 1 to 8 years. Consequently, these samples should be representative for potential variations in tissue processing and storage conditions by different laboratories in the last decade. In total, we isolated 69 areas or different numbers of nuclei from 52 paraffin blocks and applied sequence-specific PCRs or CGH after whole genome amplification (Table 1) ▶ . PCR for D5S500 or D17S800 worked reliably with 66 of the 69 DNA samples and so far 28 from 29 samples were successfully evaluated by CGH.

Discussion

Here we show that SCOMP can be adapted for the amplification of DNA isolated from microdissected formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue samples. The sensitivity and reproducibility of the method for freshly isolated cells was already known, 14 but the method had not been tested on archival samples before. The publication of numerous protocols 5-13 for whole genome amplification in the last few years suggests that many scientists still have difficulties in reliably extracting and amplifying small amounts of DNA from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues. This prompted us to carefully investigate the potential of SCOMP for this application. In contrast to methods based on primer extension preamplification or DOP-PCR, which use degenerated or partially degenerated primers, SCOMP exploits the high sensitivity and specificity of a single primer that binds to a sequence ligated to enzymatically restricted DNA. The effectiveness of the two approaches was therefore directly compared. Although for DOP-PCR we needed 5000 cells to result in a hybridization that meets the standard requirements for CGH, SCOMP amplification produced much clearer CGH profiles with as few as 20 nuclei from archival tissues.

When we analyzed factors that might influence the DNA quality, formalin fixation alone was not found to inhibit successful amplification by SCOMP. Effective SCOMP amplification and subsequent CGH was possible with only three freshly fixed cells incubated for 20 and 40 hours in buffered formalin. Using material from routine histopathology, we first investigated the effect of prolonged proteinase K digestion and the consequences of long storage times. Digestion for 15 hours worked reliably, however higher cell numbers were needed with increasing storage age of the samples, making storage time the most important variable disturbing SCOMP. Negative effects were particularly noted for MseI fragments longer than 400 bp, suggesting substantial DNA degradation throughout time, a finding that might also explain the failure of DOP-PCR, in which primer binding is estimated to occur every 4 kb. 3 Fragments of this length might rarely be present in older samples. In contrast, MseI restriction sites are present every 200 to 300 bp on average. 14 To achieve amplification of degraded DNA that had lost MseI sites, we attempted to enzymatically modify the fragmented DNA. Although the polishing and amplification protocol worked well on tissue <1 year, it was less efficient with older samples than standard SCOMP. Using the latter protocol we were able to amplify the genome of 20 cells even from a 7-year-old lymph node and to successfully perform CGH. To our knowledge, this is the lowest cell number from which successful CGH was achieved with formalin-fixed tissue. Minor modifications of the original protocol 14 included prolongation of the proteinase K incubation, and twice the amount of the primary PCR product for subsequent reactions. Nevertheless, only 1.25 μl of the primary PCR product are needed for a successful labeling reaction.

When the primary PCR products derived from SCOMP are used for loss of heterozygosity analysis, sample age and MseI fragment size have the highest impact on amplification success. We found, as a general rule, that older samples require microsatellite markers located on small MseI fragments. We recommend selecting informative markers on MseI fragments with a length of 400 bp and less. The exact mechanisms of DNA degradation remain unclear. It could be caused by insufficient or excessive tissue fixation, unfavorable storage conditions, or adverse variation in temperature. In addition, several factors will compromise the SCOMP reaction, such as unbuffered formalin, heat denaturation of the DNA before restriction digest, and potential inhibitors present in one of the fixation reagents. Because several factors that hamper PCR amplification have already been described, and whereas others might still be unknown, a comprehensive analysis of possible negative factors was beyond the scope of this study. Instead, the practicability of SCOMP was tested on 52 tissue blocks from three different pathology departments from Germany. Because the blocks, randomly selected from the past 8 years, were independently processed by the different routine laboratories the successful amplification by SCOMP on >90% of the samples proves the reliability and the reproducibility of the protocol.

The potential of SCOMP became fully evident when we compared the CGH results obtained from different cell numbers of the same paraffin-embedded tissue. Here, we found that the restriction to small confined tumor areas provides additional information of selected genomic aberrations. Because many unaffected chromosomes displayed equally normal CGH ratios and the high-copy amplification on 17q12 was seen in all samples, it is evident that the additional genetic alterations were blurred by clonal heterogeneity or by contaminating DNA from normal cells in the samples with increased cell numbers. This finding is particularly important, because it has been found that tumor heterogeneity is frequent in early stages of tumorigenesis. 21, 22 Unraveling the evolution of early neoplastic lesions is dependent on methods that can reliably depict the diversification of different tumor cell clones within the primary lesion. SCOMP should provide a valuable tool to perform such studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hans Arnholdt, Department of Pathology, Zentralklinikum Augsburg for the supply with tumor samples; Stefan Hosch, Department of Surgery, University Hospital Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany, for providing the cell line PT1590; Jürgen Kraus from the Institute of Human Genetics, Technical University Munich, Germany, for the CGH data of PT1590; and Manfred Meyer and Beate Luthardt for excellent technical support.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Christoph A. Klein, Institut für Immunologie, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Goethestr. 31, D-80336 München, Germany. E-mail: christoph.klein@ifi.med.uni-muenchen.de.

Supported by the Sonderforschungsbereich (grant 456) and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant STO 464/1-1).

References

- 1.Schütze K, Lahr G: Identification of expressed genes by laser-mediated manipulation of single cells. Nat Biotechnol 1998, 16:737-742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker I, Becker KF, Rohrl MH, Minkus G, Schütze K, Höfler H: Single-cell mutation analysis of tumors from stained histologic slides. Lab Invest 1996, 75:801-807 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Telenius H, Carter NP, Bebb CE, Nordenskjold M, Ponder BA, Tunnacliffe A: Degenerate oligonucleotide-primed PCR: general amplification of target DNA by a single degenerate primer. Genomics 1992, 13:718-725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu K, Tang Y, Grifo JA, Rosenwaks Z, Cohen J: Primer extension preamplification for detection of multiple genetic loci from single human blastomeres. Hum Reprod 1993, 8:2206-2210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Speicher MR, du Manoir S, Schrock E, Holtgreve-Grez H, Schoell B, Lengauer C, Cremer T, Ried T: Molecular cytogenetic analysis of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded solid tumors by comparative genomic hybridization after universal DNA-amplification. Hum Mol Genet 1993, 2:1907-1914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuukasjarvi T, Tanner M, Pennanen S, Karhu R, Visakorpi T, Isola J: Optimizing DOP-PCR for universal amplification of small DNA samples in comparative genomic hybridization. Genes Chromosom Cancer 1997, 18:94-101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weber RG, Scheer M, Born IA, Joos S, Cobbers JM, Hofele C, Reifenberger G, Zoller JE, Lichter P: Recurrent chromosomal imbalances detected in biopsy material from oral premalignant and malignant lesions by combined tissue microdissection, universal DNA amplification, and comparative genomic hybridization. Am J Pathol 1998, 153:295-303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang Q, Schantz SP, Rao PH, Mo J, McCormick SA, Chaganti RS: Improving degenerate oligonucleotide primed PCR-comparative genomic hybridization for analysis of DNA copy number changes in tumors. Genes Chromosom Cancer 2000, 28:395-403 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbaux S, Poirier O, Cambien F: Use of degenerate oligonucleotide primed PCR (DOP-PCR) for the genotyping of low-concentration DNA samples. J Mol Med 2001, 79:329-332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirose Y, Aldape K, Takahashi M, Berger MS, Feuerstein BG: Tissue microdissection and degenerate oligonucleotide primed-polymerase chain reaction (DOP-PCR) is an effective method to analyze genetic aberrations in invasive tumors. J Mol Diagn 2001, 3:62-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larsen J, Ottesen AM, Lundsteen C, Leffers H, Larsen JK: Optimization of DOP-PCR amplification of DNA for high-resolution comparative genomic hybridization analysis. Cytometry 2001, 44:317-325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dietmaier W, Hartmann A, Wallinger S, Heinmoller E, Kerner T, Endl E, Jauch KW, Hofstadter F, Ruschoff J: Multiple mutation analyses in single tumor cells with improved whole genome amplification. Am J Pathol 1999, 154:83-95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casas E, Kirkpatrick BW: Evaluation of different amplification protocols for use in primer-extension preamplification. Biotechniques 1996, 20:219-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein CA, Schmidt-Kittler O, Schardt JA, Pantel K, Speicher MR, Riethmuller G: Comparative genomic hybridization, loss of heterozygosity, and DNA sequence analysis of single cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999, 96:4494-4499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyytinen E, Visakorpi T, Kallioniemi A, Kallioniemi OP, Isola JJ: Improved technique for analysis of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumors by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Cytometry 1994, 16:93-99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.du Manoir S, Schrock E, Bentz M, Speicher MR, Joos S, Ried T, Lichter P, Cremer T: Quantitative analysis of comparative genomic hybridization. Cytometry 1995, 19:27-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Litt M, Hauge X, Sharma V: Shadow bands seen when typing polymorphic dinucleotide repeats: some causes and cures. Biotechniques 1993, 15:280-284 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goelz SE, Hamilton SR, Vogelstein B: Purification of DNA from formaldehyde fixed and paraffin embedded human tissue. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1985, 130:118-126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yagi N, Satonaka K, Horio M, Shimogaki H, Tokuda Y, Maeda S: The role of DNase and EDTA on DNA degradation in formaldehyde fixed tissues. Biotech Histochem 1996, 71:123-129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hosch S, Kraus J, Scheunemann P, Izbicki JR, Schneider C, Schumacher U, Witter K, Speicher MR, Pantel K: Malignant potential and cytogenetic characteristics of occult disseminated tumor cells in esophageal cancer. Cancer Res 2000, 60:6836-6840 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujii H, Marsh C, Cairns P, Sidransky D, Gabrielson E: Genetic divergence in the clonal evolution of breast cancer. Cancer Res 1996, 56:1493-1497 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrett MT, Sanchez CA, Prevo LJ, Wong DJ, Galipeau PC, Paulson TG, Rabinovitch PS, Reid BJ: Evolution of neoplastic cell lineages in Barrett oesophagus. Nat Genet 1999, 22:106-109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]