Abstract

T lymphocytes localize within lesions of two diametrically opposed expressions of atherosclerosis: stenosis-producing plaques and ectasia-producing abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). TH1 immune responses appear to predominate in human stenotic lesions. However, little information exists regarding the nature of the T-cell infiltrate in AAAs. We demonstrate here that AAAs predominantly express TH2-associated cytokines and correspondingly lack mediators associated with the TH1 response as determined by Western blot and immunohistochemical analysis. In particular, aneurysmal tissue expressed interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, and IL-10, cytokines not or only faintly detected in nondiseased tissue or stenotic atheroma. In contrast, AAAs contained low levels of the TH1 characteristic cytokines IL-2 and IL-15, which are amply expressed in stenotic lesions. Notably, stenotic lesions, but not AAAs, contained mature forms of the interferon-γ-inducing cytokines IL-12 and IL-18 as well as the IL-18-processing enzyme caspase-1. Moreover, aneurysmal tissue lacked the receptor for interferon-γ, although both types of lesions contained this TH1-promoting cytokine. These findings suggest that the functional repertoire of T cells differs in stenotic and aneurysmal lesions, and provide a novel framework for understanding the mechanisms of these diametrically opposite expressions of atherosclerosis.

In the United States alone abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) affect 3% of individuals 60 years or older, necessitate 46,000 surgical interventions, and cause ∼15,000 deaths annually. 1 The prevalence of AAA will increase as the population ages and thus will continue to entail considerable morbidity, mortality, and medical expense. Despite considerable descriptive knowledge of the pathomorphology of AAA, 2,3 insufficient understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying its pathogenesis currently limits the prevention and treatment of this human disease.

No mechanistic model yet exists that explains why atherosclerosis can have diametrically opposed expressions: aneurysm versus occlusive disease. Previous work by us and other investigators, however, revealed certain salient morphological characteristics in the pathophysiology of aortic aneurysm, including the profound inflammation characterized by abundant infiltrates of leukocytes such as T lymphocytes. 4-7 Studies demonstrating that stiffness of the aneurysmal aortic wall does not correlate with the risk for rupture further supported the hypothesis that the inflammatory composition, rather than morphology or mechanics alone, determines the risk for acute clinical complications. 8 Moreover, inflammatory infiltrates and aneurysmal enlargement correlate temporally, suggesting that the inflammatory cells may participate in the destruction of the aneurysmal aortic wall. 9 Despite their abundance, 4,6 the functional phenotype of the T lymphocytes found in AAAs remains mostly speculative.

T lymphocytes include both helper T cells (TH) and cytolytic T cells. Within the helper subset, TH1 cells secrete one characteristic set of cytokines [eg, interleukin (IL)-2, interferon (IFN)-γ, and lymphotoxin] and TH2 cells secrete another, nonoverlapping set of cytokines (eg, IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, IL-10, IL-13). 10,11 Among the prototypical TH1 cytokines, IFN-γ has attracted particular interest, because this mediator activates macrophages; enhances inflammatory cell recruitment by augmenting cytokine, chemokine, and adhesion molecule expression; and amplifies immune responses in several ways, including increasing levels of MHC I and II molecules on antigen-presenting cells and endothelium. IFN-γ, synergistically induced by IL-12 and IL-18, accelerates experimental atherosclerosis. 12-14 In contrast, TH2-derived cytokines, in particular IL-4 and IL-10, tend to limit the cytotoxic potential of macrophages and to reduce the expression of proinflammatory mediators such as cytokines or matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), 15-19 enzymes that participate in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. 20,21 Accordingly, a deficiency in IL-10 promotes experimental atherosclerosis. 19 The cytokines produced by TH1 or TH2 cells tend to sustain their own development and antagonize each other. 10,11 IFN-γ produced by TH1 cells, for example, directly antagonizes TH2 cells. IFN-γ also activates macrophages to produce more IL-12 and IL-18 (originally termed IGIF, interferon gamma-inducing factor), 22,23 which leads to the further expansion of TH1 cells and inhibition of TH2 cells. Conversely, IL-4 produced by TH2 cells antagonizes the promotion of a TH1-directed immune response.

Recent studies from several groups, including our own, demonstrated a predominance of the TH1 lymphocytic subpopulation and its mediators within atherosclerotic lesions. 24-27 In particular, these studies demonstrated in atherosclerotic lesions expression of the TH1 response-promoting cytokines IL-2, IL-12, IL-15, IL-18, CD40L, and IFN-γ, as well as the absence of the TH2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10.

The present study tested the hypothesis that AAA and stenotic atheroma differ in the predominance of TH2-derived versus TH1-derived cytokines. Such distinction would provide novel molecular insight into potential pathways underlying these two diametrically opposed expressions of atherosclerosis.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Immunohistochemical and Western blot analysis used the following antibodies: mouse anti-human IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-15, and IL-18, as well as goat anti-human IL-18Rα (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN); mouse anti-human IL-12p35 (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA); rabbit anti-human caspase-1p20 and CD40L (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), mouse anti-human IFN-γ and IFN-γRα (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA); and mouse anti-human CD3 and CD68 (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA). To control for specificity a rabbit anti-human IL-4 and IL-10 antibody was used (Santa Cruz).

Surgical specimens of human carotid plaques were obtained from endarterectomies performed on eight different patients. Aneurysmal tissue was obtained as discarded material from AAA repair surgery on eight different patients. Nonatherosclerotic specimens were obtained from carotid arteries from autopsies (n = 4) and aortas from cardiac transplantation donors (n = 3). All specimens were obtained by protocols approved by the Human Investigation Review Committee at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. For the experiments, the fresh-frozen specimen were inspected visually and cut longitudinally into two equally diseased portions, which were applied in parallel to Western blot and immunohistochemical analysis, respectively.

Western Blot Analysis

Frozen nonatherosclerotic (n = 7), atheromatous human carotid (n = 8), or AAA specimens (n = 8) were homogenized (Ultra-turrax T 25; IKA-Labortechnik) and lysed (0.3 g tissue/ml lysis buffer: 10 mmol/L NaH2PO4, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.2% NaN3, 5 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 20 μg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, 0.1 mmol/L phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, and 1 μg/ml leupeptin), as described previously. 28,29 The lysates were clarified (16,000 × g, 15 minutes) and the protein concentration for each tissue extract was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Total protein (50 μg) was separated by standard sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and blotted to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using a semidry blotting apparatus (3 mA/cm2, 60 minutes; Bio-Rad). Blots were blocked, and primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in 5% defatted dry milk/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/0.1% Tween 20. Primary antibodies were applied in the following concentrations: mouse anti-human IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-15, IFN-γ, and goat anti-human IL-18Rα at 2 μg/ml; mouse anti-human IL-12p35, IL-18, IFN-γRα, and rabbit anti-human CD40L at 1 μg/ml; and rabbit anti-human caspase-1p20 at 0.5 μg/ml. After 1 hour of incubation with the primary antibody, blots were washed three times (PBS/0.1% Tween 20) and the respective secondary, peroxidase-conjugated antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) was added for another hour. Finally, the blots were washed (20 minutes in PBS/0.1% Tween 20) and immunoreactive proteins visualized using the SuperSignal West Femto kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Densitometric analysis of immunoreactive bands used GelPro software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD), applied to digital images of the respective Western blots.

Immunohistochemistry

Serial cryostat sections (5 μm) of surgical specimens of seven nonatherosclerotic carotids and aortas, eight atheromatous carotid plaques, and eight AAAs, were cut, air-dried onto microscope slides, fixed in acetone (−20°C, for 5 minutes), and preincubated with PBS containing 0.3% hydrogen peroxide to suppress endogenous peroxidase activity. Subsequently, sections were incubated (30 minutes) with primary [mouse anti-human IL-2, IL-4, IL-10 (all 1:50), IL-12p35, IL-15 (both 1:100), IL-18 (1:200), IFN-γRα (1:30), or rabbit anti-human caspase-1p20, CD40L (both 1:100)] or control antibody, diluted in PBS supplemented with 5% appropriate serum. Staining was completed using the LSAB Kit (DAKO) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. In contrast, the goat anti-human IL-18Rα (1:150) antibody was applied for 90 minutes, sections were incubated (45 minutes) with the respective biotinylated secondary antibody (Vector, Burlingame, CA), followed by avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (Vectastain ABC kit, Vector) and antibody binding was visualized with 3-amino-9-ethyl carbazole (Vector). Nuclei were counterstained by Gill’s hematoxylin.

For co-localization of IL-4 with T lymphocytes and macrophages rabbit anti-human-IL-4 antibody (1:150) was applied for 90 minutes, followed by biotinylated secondary antibody (45 minutes) and Texas Red-conjugated streptavidin (20 minutes; Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). Subsequently, the avidin/biotin blocking kit (Vector) was applied, followed by overnight incubation (4°C) with mouse anti-human CD3 or CD68 antibodies. Finally, biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG antibody was applied (45 minutes) followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated streptavidin (Amersham).

Statistical Analysis

Data obtained from the densitometric analysis of immunoreactive bands are presented as fold regulation (mean ± SD) and were compared between atherosclerotic and aneurysmal tissue using the Student’s t-test. A value of P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

To test the hypothesis that TH1 or TH2 responses predominate in the pathogenesis of human AAAs, we analyzed the expression of markers characteristic for either T-cell subset in human AAAs (n = 8) in situ. Observations on AAA tissue were compared with those on nondiseased (n = 7) tissue as well as atherosclerotic plaques (n = 8).

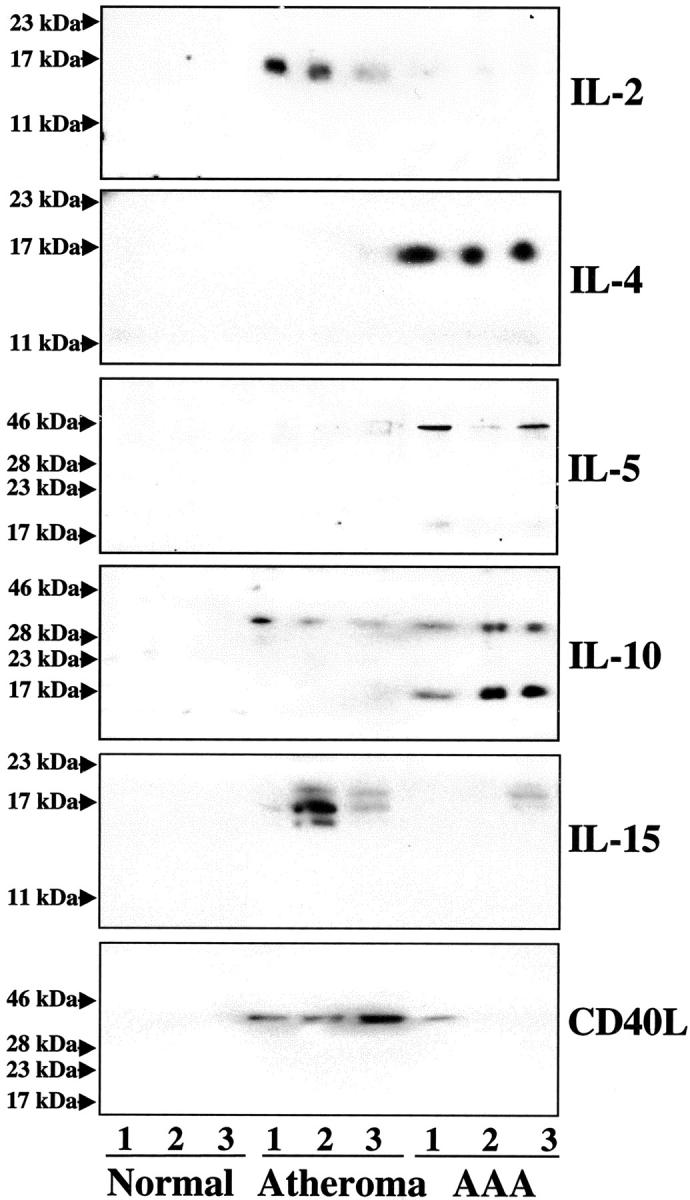

Interestingly, extracts of human AAA tissue displayed elevated expression of TH2- and little or no expression of TH1-associated cytokines. In particular, human AAA tissue contained the TH2 type cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10, mediators not observed in extracts of nondiseased tissue (Figure 1) ▶ . Notably, extracts of human atherosclerotic plaques also showed no immunoreactive IL-4 and, compared to AAA, much lower concentrations of IL-5 (7.4 ± 3.7-fold, P < 0.03) and IL-10 (3.9 ± 2.1-fold, P < 0.05); both immunoreactive bands (18 and 36 kd) were included in the quantification, because they presumably correspond to the monomeric and dimeric form of IL-10. In contrast, AAA tissue did not contain IL-2, a prototypical cytokine of the TH1 subset, expressed abundantly in extracts of atherosclerotic plaques. 27,30,31 Moreover, extracts of AAAs contained significantly less IL-15 (8.2 ± 5.5-fold, P < 0.01) or CD40L (6.2 ± 4.8-fold, P < 0.05), other characteristic TH1 cytokines, compared to extracts of atherosclerotic plaques (Figure 1) ▶ . Nonatherosclerotic tissue did not contain any detectable cytokines (Figure 1) ▶ .

Figure 1.

Human AAAs contain TH2-associated cytokines. Protein extracts (50 μg/lane) of nondiseased carotids (Normal), atheromatous carotids, and AAAs were applied to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and subsequent Western blot analysis using either a mouse anti-human IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-15, or CD40L antibody. The positions of the molecular weight markers are indicated on the left. Analysis of tissue extracts obtained from seven nonatherosclerotic, eight atherosclerotic, and eight AAA surgical specimens from different individuals showed similar results.

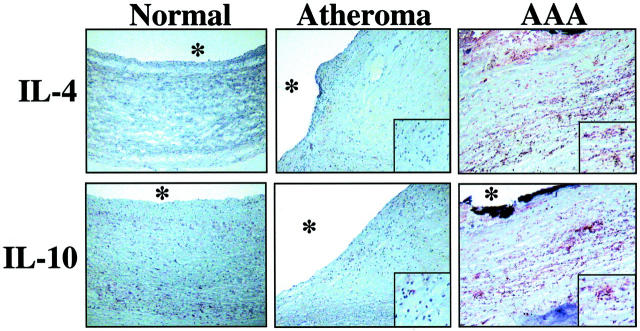

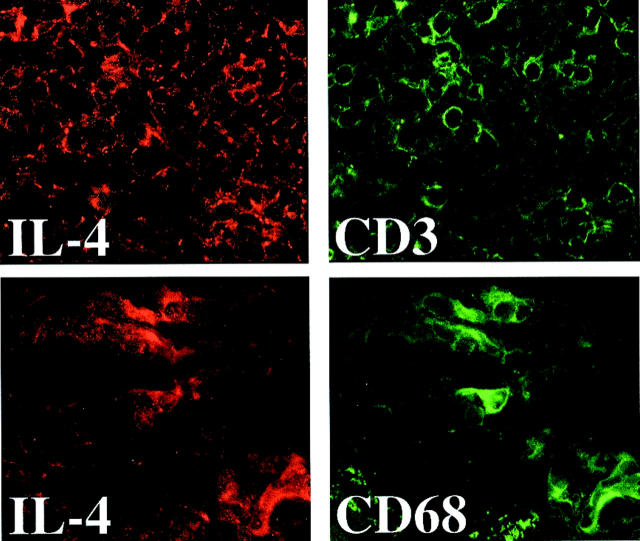

Immunohistochemical studies further supported the predominance of TH2-associated cytokines and the absence of markers of the TH1 subpopulation in human AAA. In accord with the Western blot analysis, AAA tissue showed enhanced staining for TH2 cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10 (Figure 2 ▶ , right), and diminished or absent staining for characteristic TH1 cytokines such as IL-2, IL-15, or CD40L (data not shown), compared to nondiseased tissue (Figure 2 ▶ , left) or atherosclerotic plaques (Figure 2 ▶ , middle). The TH2 cytokines localized predominantly in T lymphocyte- as well as macrophage-enriched regions, as demonstrated by immunofluorescence double labeling for IL-4 with either CD3 or CD68, respectively (Figure 3) ▶ .

Figure 2.

Human AAAs express the characteristic TH2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-10. Serial cryostat sections of frozen specimens of human nondiseased carotids (Normal), carotid atheroma, or AAA were stained with either mouse anti-human IL-4 or IL-10 antibody. The asterisks indicate the lumen of the vessel. The inserts show higher magnifications (×400) of the T cell/macrophage-enriched area. Analysis of tissue obtained from seven nonatherosclerotic, eight atherosclerotic, and eight AAA surgical specimens from different individuals showed similar results.

Figure 3.

The TH2 cytokine IL-4 colocalizes with immunocompetent cells. Serial cryostat sections of frozen specimens of human AAAs were applied to immunofluorescence double labeling using anti-human IL-4 (left; red) as well as anti-human CD3 (top right; T lymphocytes, green), or CD68 (bottom right; macrophages, green) antibody. Analysis of three AAA surgical specimens from different individuals showed similar results.

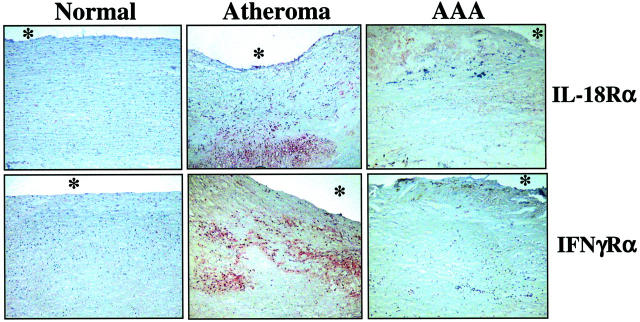

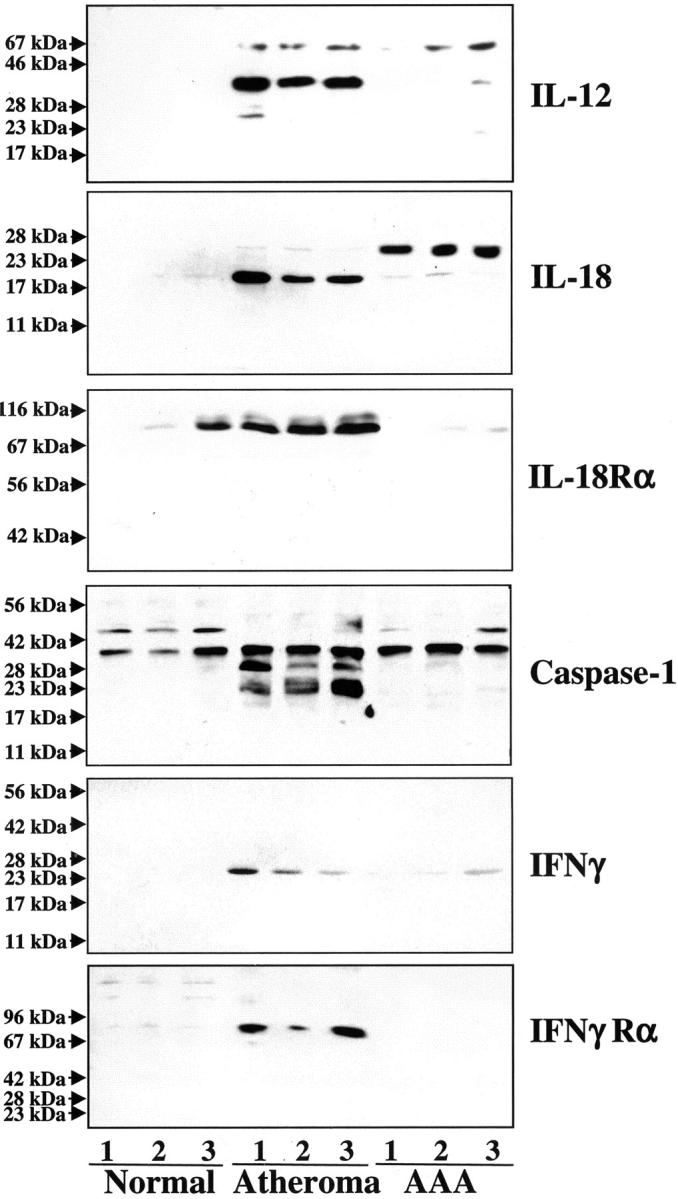

Because IFN-γ participates proximally in engendering TH1 responses predominant in occlusive atheroma, and interruption of IFN-γ signaling markedly diminishes experimental occlusive atherosclerosis, 12-14 we further analyzed the expression of this cytokine and its inducers IL-12 and IL-18 in human AAA. Extracts of nondiseased arterial tissue (n = 7) contained little or no IL-12 (Figure 4) ▶ . In contrast, atheromatous tissue (n = 8) strongly expressed this cytokine when compared to extracts of AAA (n = 8) tissue (9.8 ± 2.5-fold increase, P < 0.01; both, the 35- and 70-kd band were included in the quantification because they presumably correspond to the IL-12p35 subunit and the IL-12p70 dimer) (Figure 4) ▶ . Moreover, AAA extracts expressed IL-18 predominantly as the inactive 24-kd precursor, whereas extracts of human atheroma contained predominantly the mature 18-kd form, in accord with previous observations. 29 In addition to the ligand, AAA specimens also expressed lower levels of the IL-18 receptor (IL-18Rα) compared to atherosclerotic tissue (9.0 ± 2.2-fold, P > 0.01) (Figure 4) ▶ . In accord with the differential expression of mature IL-18, extracts of human atheroma, but not of AAA, contained immunoreactive bands corresponding to the active p20-subunit of the IL-18-converting enzyme, caspase-1 (Figure 4) ▶ . In contrast, nondiseased arteries and aneurysmal specimens contained only the inactive caspase-1 precursor. Although extracts of AAA contained less immunoreactive IFN-γ (2.8 ± 1.3-fold, P < 0.05) than those obtained from stenotic atheroma (Figure 4) ▶ , consistent with the diminished expression of the IFN-γ-inducing factors IL-12 and IL-18, this typical TH1 cytokine localized in both types of diseased tissue. However, analysis of the expression of the receptor for IFN-γ (IFN-γRα) provided evidence for impaired IFN-γ-signaling in AAA. All nondiseased as well as AAA specimens analyzed lacked immunoreactive IFN-γRα, whereas extracts of human atheroma yielded immunoreactive bands in Western blot analysis (Figure 4) ▶ . In accord with the biochemical data obtained with protein extracts, aneurysmal tissue exhibited diminished expression of the receptor for the IFN-γ-inducing factor IL-18, IL-18Rα, and lack of the IFN-γ receptor in situ, as determined by immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 5) ▶ .

Figure 4.

Expression of IFN-γ-associated mediators is attenuated in human AAAs. Protein extracts (50 μg/lane) of nondiseased arterial tissue (normal), atherosclerotic lesions, and AAA (specimens obtained from three different donors are shown) were applied to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and subsequent Western blot analysis using either an anti-human IL-12p40, IL-18, IL-18 receptor α (IL-18Rα), caspase-1p20, IFN-γ, or IFN-γ receptor-α (IFN-γRα) antibody. The positions of the molecular weight markers are indicated on the left. Analysis of extracts of a total of seven nonatherosclerotic, eight atherosclerotic, and eight AAA specimens from different individuals showed similar results.

Figure 5.

Expression of receptors for the TH1 cytokines IL-18 and IFN-γ is diminished in human AAA. Serial cryostat sections of frozen specimens of nondiseased human arteries (Normal), carotid atheroma, or AAA were stained with antibodies recognizing either the human IL-18 receptor-α (IL-18Rα) or IFN-γ receptor-α (IFN-γRα). The asterisks indicate the lumen of the vessel. Analysis of tissues obtained from seven nonatherosclerotic, eight atherosclerotic, and eight AAA specimens from different individuals yielded similar results.

Discussion

Risk factors for AAA and atheroma differ. Risk of atherosclerosis strongly correlates with the lipoprotein profile, the few eminent risk factors identified for aneurysmal disease include smoking and male gender. 32 Interestingly, one of the major risk factors for human AAA, smoking, enhances the proliferation of the T-helper cell population, 33,34 a predominant cell type of the aneurysmal inflammatory infiltrate. The balance between TH1- and TH2-type responses influences the progression of numerous inflammatory diseases, including atherosclerosis. 18,27 The present study provides evidence that, in contrast to stenotic atherosclerotic plaques, human AAAs display a predominant TH2 response, as determined by the accumulation of typical TH2 cytokines and the absence or low expression levels of characteristic TH1 cytokines, in particular the IFN-γ signaling pathway. This pattern of cytokine expression may reinforce itself, because the TH2 lymphocyte subset not only promotes its own growth and differentiation by virtue of corresponding cytokine synthesis, but also suppresses the proliferation and differentiation of the TH1 subset. 10,11

In particular, the TH2 cytokine IL-4, overexpressed in AAA rather than human atheroma, not only promotes the proliferation of T lymphocytes but also specifically rescues TH2, but not TH1 cells, from apoptosis. 35 In contrast, IL-2, expressed in atheroma rather than AAA, prevents apoptosis of TH1, but not of TH2 cells. 35 In addition, the TH2 cytokine IL-10 promotes the death of TH1 cells. 36,37 Thus, elevated expression of IL-4 and IL-10 in combination with the low abundance of IL-2 and participants in the IFN-γ-signaling cascade, namely IL-12, IL-18, and IFN-γ (all TH1-promoting cytokines), might foster the TH2-dominated immune response in AAA. On the other hand, we and others recently demonstrated the in vitro and in vivo relevance for the characteristic TH1 cytokines IL-12, IL-18, and IFN-γ in stenotic atheroma. 12-14,29,38,39 Mice deficient for these cytokines have attenuated TH1 activities. 40,41 The lack of active IL-12, IL-18, IFN-γ, and their receptors in AAA supports our hypothesis that distinct TH cell subsets predominate in occlusive atheroma and AAA. Of note, the impaired IFN-γ signaling observed in this study might explain the lack of IL-12, because IFN-γ augments both IL-12 production and expression of the IL-12 receptor, pathways typically promoting expansion of the TH1 subset. 42,43

In addition to the numerical predominance of TH2 cells, the cytokines overexpressed in AAA might directly modulate the pathological mechanisms underlying AAA. Aneurysms exhibit destruction of the normal arterial architecture, particularly the smooth muscle cell-enriched tunica media. Apoptosis of smooth muscle cells may contribute to aneurysm formation, 6,44 dependent at least in part on Fas ligand (FasL) expressed on T lymphocytes. 6,45 Interestingly, although both TH1 and TH2 lymphocytes express Fas and FasL, only the TH2 subset expresses high levels of a Fas-associated phosphatase (FAP-1), which probably inhibits Fas signaling, causing death of TH1 and selective survival of TH2 lymphocytes in AAA. 46 Despite the lack of direct evidence that typical TH2 cytokines can promote Fas-mediated apoptosis in smooth muscle cells, IL-4 and IL-10 sensitize nonlymphocytic cell types to Fas-mediated cell death 47 and can induce Fas resistance in B cells. 48 Interestingly, Fas-mediated apoptosis leads to the expression of IL-10 in lymphoid cells, suggesting a potential auto/paracrine feedback loop promoting apoptosis and the expression of TH2 typical cytokines in AAA. 49

TH2 cytokines might further promote the pathogenesis of AAA through another pathway, the degradation of extracellular matrix macromolecules such as collagen and/or elastin. Cytokines of the TH2 subset augment collagenolytic and elastolytic activities in cell types associated with AAA. IL-4 and IL-10 elicit the expression of MMPs, such as the interstitial collagenase MMP-1 or MMP-3, in mononuclear phagocytes and smooth muscle cells, 17,50 a function reversed in the presence of IL-1β or tumor necrosis factor-α, cytokines that likely participate in atherosclerotic plaque formation but scant in AAA. 51,52 Moreover, impaired IFN-γ signaling in AAA might heighten overexpression of matrix-degrading enzymes because this prototypical TH1 cytokine potently antagonizes IL-1β- or tumor necrosis factor-α-induced MMP expression. Thus, the prevalence of TH2 immune mediators in AAA might foster a pattern of matrix-degrading enzymes different from that observed in atherosclerotic plaques, in which a TH1 immune response predominates. 27

In addition to collagen degradation, elastolysis figures prominently in the pathogenesis of AAA. Increased tissue and serum levels of elastase activity and diminished elastin content compared to nondiseased or atherosclerotic plaque tissue characterizes AAA, 53 and neutrophil granulocytes probably contribute to the excessive elastolytic activity. 54 Chemoattraction of neutrophils by IL-4 and IL-5 55 might thus provide another pathway by which TH2 cytokines could promote AAA formation. In addition, elastase released from neutrophils stimulates the expression of IL-10 by leukocytes, 56 potentially enabling operation of a positive feedback loop favoring elastolysis.

As suggested by the present data and as proposed by others, the pathogenesis of aneurysmal disease may involve elements distinct from usual atherosclerosis. Indeed, AAA and stenotic atherosclerotic plaques appear to represent diametrically opposed expressions of arterial disease involving distinct but overlapping risk factors, chronology, and pathogenic pathways. The present report provides evidence that a shift in the balance of TH1- and TH2-mediated immune responses, and thus the inflammatory response in the vessel wall, eventually characterizes these two diametrically opposed expressions of atherosclerosis, that encompass the two extreme cases of arterial remodeling.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eugenia Shvartz, Samantha LaClair, and Elissa Simon-Morrissey (Brigham and Women’s Hospital) for skillful technical assistance, and Karen E. Williams (Brigham and Women’s Hospital) for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Uwe Schönbeck, Cardiovascular Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 221 Longwood Ave., EBRC 309a, Boston, MA 02115. E-mail: uschoenbeck@rics.bwh.harvard.edu.

Supported in part by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL-56985 and HL-34636 to P. L.) and the Fondation Leducq.

U. S. and G. K. S. contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Stanley JC, Barnes RW, Ernst CB, Hertzer NR, Mannick JA, Moore WS: Vascular surgery in the United States: workforce issues. Report of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the International Society for Cardiovascular Surgery, North American Chapter, Committee on Workforce Issues. J Vasc Surg 1996, 23:172-181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel MI, Hardman DT, Fisher CM, Appleberg M: Current views on the pathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Am Coll Surg 1995, 181:371-382 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powell J, Greenhalgh RM: Cellular, enzymatic, and genetic factors in the pathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg 1989, 9:297-304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koch AE, Kunkel SL, Pearce WH, Shah MR, Parikh D, Evanoff HL, Haines GK, Burdick MD, Strieter RM: Enhanced production of the chemotactic cytokines interleukin-8 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Am J Pathol 1993, 142:1423-1431 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yen HC, Lee FY, Chau LY: Analysis of the T cell receptor V beta repertoire in human aortic aneurysms. Atherosclerosis 1997, 135:29-36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henderson EL, Geng YJ, Sukhova GK, Whittemore AD, Knox J, Libby P: Death of smooth muscle cells and expression of mediators of apoptosis by T lymphocytes in human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Circulation 1999, 99:96-104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bobryshev YV, Lord RS: Vascular-associated lymphoid tissue (VALT) involvement in aortic aneurysm. Atherosclerosis 2001, 154:15-21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonesson B, Sandgren T, Lanne T: Abdominal aortic aneurysm wall mechanics and their relation to risk of rupture. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 1999, 18:487-493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anidjar S, Dobrin PB, Eichorst M, Graham GP, Chejfec G: Correlation of inflammatory infiltrate with the enlargement of experimental aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg 1992, 16:139-147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abbas AK, Murphy KM, Sher A: Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes. Nature 1996, 383:787-793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mosmann TR, Li L, Hengartnner H, Kagi D, Fu W, Sad S: Differentiation and functions of T cell subsets. Ciba Found Symp 1997, 204:148-154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta S, Pablo AM, Jiang X, Wang N, Tall AR, Schindler C: IFN-gamma potentiates atherosclerosis in ApoE knock-out mice. J Clin Invest 1997, 99:2752-2761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tellides G, Tereb DA, Kirkiles-Smith NC, Kim RW, Wilson JH, Schechner JS, Lorber MI, Pober JS: Interferon-gamma elicits arteriosclerosis in the absence of leukocytes. Nature 2000, 403:207-211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitman SC, Ravisankar P, Elam H, Daugherty A: Exogenous interferon-gamma enhances atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E−/− mice. Am J Pathol 2000, 157:1819-1824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ensminger SM, Spriewald BM, Sorensen HV, Witzke O, Flashman EG, Bushell A, Morris PJ, Rose ML, Rahemtulla A, Wood KJ: Critical role for IL-4 in the development of transplant arteriosclerosis in the absence of CD40-CD154 costimulation. J Immunol 2001, 167:532-541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.George J, Shoenfeld Y, Gilburd B, Afek A, Shaish A, Harats D: Requisite role for interleukin-4 in the acceleration of fatty streaks induced by heat shock protein 65 or Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Circ Res 2000, 86:1203-1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sasaguri T, Arima N, Tanimoto A, Shimajiri S, Hamada T, Sasaguri Y: A role for interleukin 4 in production of matrix metalloproteinase 1 by human aortic smooth muscle cells. Atherosclerosis 1998, 138:247-253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uyemura K, Demer LL, Castle SC, Jullien D, Berliner JA, Gately MK, Warrier RR, Pham N, Fogelman AM, Modlin RL: Cross-regulatory roles of interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-10 in atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest 1996, 97:2130-2138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinderski Oslund LJ, Hedrick CC, Olvera T, Hagenbaugh A, Territo M, Berliner JA, Fyfe AI: Interleukin-10 blocks atherosclerotic events in vitro and in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1999, 19:2847-2853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galis Z, Sukhova G, Lark M, Libby P: Increased expression of matrix metalloproteinases and matrix degrading activity in vulnerable regions of human atherosclerotic plaques. J Clin Invest 1994, 94:2493-2503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sukhova GK, Schönbeck U, Rabkin E, Schoen FJ, Poole AR, Billinghurst RC, Libby P: Evidence for increased collagenolysis by interstitial collagenases-1 and -3 in vulnerable human atheromatous plaques. Circulation 1999, 99:2503-2509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamura H, Tsutsi H, Komatsu T, Yutsudo M, Hakura A, Tanimoto T, Torigoe K, Okura T, Nukada Y, Hattori K, Akita K, Namba M, Tanabe F, Konishi K, Fukuda S, Kurimoto M: Cloning of a new cytokine that induces IFN-gamma production by T cells. Nature 1995, 378:88-91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ushio S, Namba M, Okura T, Hattori K, Nukada Y, Akita K, Tanabe F, Konishi K, Micallef M, Fujii M, Torigoe K, Tanimoto T, Fukuda S, Ikeda M, Okamura H, Kurimoto M: Cloning of the cDNA for human IFN-gamma-inducing factor, expression in Escherichia coli, and studies on the biologic activities of the protein. J Immunol 1996, 156:4274-4279 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Libby P, Ross R: Cytokines and growth regulatory molecules. Fuster V Ross R Topol E eds. Atherosclerosis and Coronary Artery Disease. 1996:pp 585-594 Lippincott-Raven, New York

- 25.Amento EP, Ehsani N, Palmer H, Libby P: Cytokines and growth factors positively and negatively regulate interstitial collagen gene expression in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb 1991, 11:1223-1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mach F, Schönbeck U, Sukhova GK, Bourcier T, Bonnefoy JY, Pober JS, Libby P: Functional CD40 ligand is expressed on human vascular endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and macrophages: implications for CD40-CD40 ligand signaling in atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997, 94:1931-1936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frostegard J, Ulfgren AK, Nyberg P, Hedin U, Swedenborg J, Andersson U, Hansson GK: Cytokine expression in advanced human atherosclerotic plaques: dominance of pro-inflammatory (Th1) and macrophage-stimulating cytokines. Atherosclerosis 1999, 145:33-43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young JL, Sukhova GK, Foster D, Kisiel W, Libby P, Schonbeck U: The serpin proteinase inhibitor 9 is an endogenous inhibitor of interleukin 1beta-converting enzyme (caspase-1) activity in human vascular smooth muscle cells. J Exp Med 2000, 191:1535-1544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerdes N, Sukhova GK, Libby P, Reynolds RS, Young JL, Schonbeck U: Expression of interleukin (IL)-18 and functional IL-18 receptor on human vascular endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and macrophages: implications for atherogenesis. J Exp Med 2002, 195:245-257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arbustini E, Grasso M, Diegoli M, Pucci A, Bramerio M, Ardissino D, Angoli L, de Servi S, Bramucci E, Munini A, Minzioni G, Vigano M, Specchia G: Coronary atherosclerotic plaques with and without thrombus in ischemic heart syndromes: a morphologic, immunohistochemical, and biochemical study. Am J Cardiol 1991, 68:36B-50B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramshaw AL, Roskell DE, Parums DV: Cytokine gene expression in aortic adventitial inflammation associated with advanced atherosclerosis (chronic periaortitis). J Clin Pathol 1994, 47:721-727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson RW: Basic science of abdominal aortic aneurysms: emerging therapeutic strategies for an unresolved clinical problem. Curr Opin Cardiol 1996, 11:504-518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tollerud DJ, Clark JW, Brown LM, Neuland CY, Mann DL, Pankiw-Trost LK, Blattner WA, Hoover RN: The effects of cigarette smoking on T cell subsets. A population-based survey of healthy Caucasians. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989, 139:1446-1451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanigawa T, Araki S, Nakata A, Sakurai S: Increase in the helper inducer (CD4+CD29+) T lymphocytes in smokers. Ind Health 1998, 36:78-81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zubiaga AM, Munoz E, Huber BT: IL-4 and IL-2 selectively rescue Th cell subsets from glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis. J Immunol 1992, 149:107-112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Estaquier J, Marguerite M, Sahuc F, Bessis N, Auriault C, Ameisen JC: Interleukin-10-mediated T cell apoptosis during the T helper type 2 cytokine response in murine Schistosoma mansoni parasite infection. Eur Cytokine Netw 1997, 8:153-160 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ayala A, Chung CS, Song GY, Chaudry IH: IL-10 mediation of activation-induced TH1 cell apoptosis and lymphoid dysfunction in polymicrobial sepsis. Cytokine 2001, 14:37-48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mallat Z, Corbaz A, Scoazec A, Graber P, Alouani S, Esposito B, Humbert Y, Chvatchko Y, Tedgui A: Interleukin-18/interleukin-18 binding protein signaling modulates atherosclerotic lesion development and stability. Circ Res 2001, 89:E41-E45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee TS, Yen HC, Pan CC, Chau LY: The role of interleukin 12 in the development of atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1999, 19:734-742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gately MK, Renzetti LM, Magram J, Stern AS, Adorini L, Gubler U, Presky DH: The interleukin-12/interleukin-12-receptor system: role in normal and pathologic immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol 1998, 16:495-521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takeda K, Tsutsui H, Yoshimoto T, Adachi O, Yoshida N, Kishimoto T, Okamura H, Nakanishi K, Akira S: Defective NK cell activity and Th1 response in IL-18-deficient mice. Immunity 1998, 8:383-390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Szabo SJ, Dighe AS, Gubler U, Murphy KM: Regulation of the interleukin (IL)-12R beta 2 subunit expression in developing T helper 1 (Th1) and Th2 cells. J Exp Med 1997, 185:817-824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma X, Chow JM, Gri G, Carra G, Gerosa F, Wolf SF, Dzialo R, Trinchieri G: The interleukin 12 p40 gene promoter is primed by interferon gamma in monocytic cells. J Exp Med 1996, 183:147-157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lopez-Candales A, Holmes DR, Liao S, Scott MJ, Wickline SA, Thompson RW: Decreased vascular smooth muscle cell density in medial degeneration of human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Am J Pathol 1997, 150:993-1007 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watanabe N, Arase H, Kurasawa K, Iwamoto I, Kayagaki N, Yagita H, Okumura K, Miyatake S, Saito T: Th1 and Th2 subsets equally undergo Fas-dependent and -independent activation-induced cell death. Eur J Immunol 1997, 27:1858-1864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang X, Brunner T, Carter L, Dutton RW, Rogers P, Bradley L, Sato T, Reed JC, Green D, Swain SL: Unequal death in T helper cell (Th)1 and Th2 effectors: Th1, but not Th2, effectors undergo rapid Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis. J Exp Med 1997, 185:1837-1849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yeatman CF, II, Jacobs-Helber SM, Mirmonsef P, Gillespie SR, Bouton LA, Collins HA, Sawyer ST, Shelburne CP, Ryan JJ: Combined stimulation with the T helper cell type 2 cytokines interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-10 induces mouse mast cell apoptosis. J Exp Med 2000, 192:1093-1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Foote LC, Howard RG, Marshak-Rothstein A, Rothstein TL: IL-4 induces Fas resistance in B cells. J Immunol 1996, 157:2749-2753 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gao Y, Herndon JM, Zhang H, Griffith TS, Ferguson TA: Antiinflammatory effects of CD95 ligand (FasL)-induced apoptosis. J Exp Med 1998, 188:887-896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chizzolini C, Rezzonico R, De Luca C, Burger D, Dayer JM: Th2 cell membrane factors in association with IL-4 enhance matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) while decreasing MMP-9 production by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-differentiated human monocytes. J Immunol 2000, 164:5952-5960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Borghaei RC, Rawlings PL, JR, Mochan E: Interleukin-4 suppression of interleukin-1-induced transcription of collagenase (MMP-1) and stromelysin 1 (MMP-3) in human synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum 1998, 41:1398-1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nemoto O, Yamada H, Kikuchi T, Shinmei M, Obata K, Sato H, Seiki M, Shimmei M: Suppression of matrix metalloproteinase-3 synthesis by interleukin-4 in human articular chondrocytes. J Rheumatol 1997, 24:1774-1779 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wiernicki I, Gutowski P, Ciechanowski K, Millo B, Wieczorek P, Cnotliwy M, Michalak T, Hamera T, Piatek J: Abdominal aortic aneurysm: association between haptoglobin phenotypes, elastase activity, and neutrophil count in the peripheral blood. Vasc Surg 2001, 35:345-350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cohen JR, Keegan L, Sarfati I, Danna D, Ilardi C, Wise L: Neutrophil chemotaxis and neutrophil elastase in the aortic wall in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Invest Surg 1991, 4:423-430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Caproni M, Feliciani C, Fuligni A, Salvatore E, Atani L, Bianchi B, Pour SM, Proietto G, Toto P, Coscione G, Amerio P, Fabbri P: Th2-like cytokine activity in dermatitis herpetiformis. Br J Dermatol 1998, 138:242-247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Guthrie L, Henson PM: Differential effects of apoptotic versus lysed cells on macrophage production of cytokines: role of proteases. J Immunol 2001, 166:6847-6854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]