Abstract

The cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 enzyme has been implicated as an important mediator of pulmonary fibrosis. In this study, the lung fibrotic responses were investigated in COX-1 or COX-2-deficient (−/−) mice following vanadium pentoxide (V2O5) exposure. Lung histology was normal in saline-instilled wild-type and COX-deficient mice. COX-2−/−, but not COX-1−/− or wild-type mice, exhibited severe inflammatory responses by 3 days following V2O5 exposure and developed pulmonary fibrosis 2 weeks post-V2O5 exposure. Western blot analysis and immunohistochemistry showed that COX-1 protein was present in type 2 epithelial cells, bronchial epithelial cells, and airway smooth muscle cells of saline or V2O5-exposed wild-type and COX-2−/− mice. COX-2 protein was present in Clara cells of wild-type and COX-1−/− terminal bronchioles and was strongly induced 24 hours after V2O5 exposure. Prostaglandin (PG) E2 levels in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid from wild-type and COX-1−/− mice were significantly up-regulated by V2O5 exposure within 24 hours, whereas PGE2 was not up-regulated in COX-2−/− BAL fluid. Tumor necrosis factor-α was elevated in the BAL fluid from all genotypes after V2O5 exposure, but was significantly and chronically elevated in the BAL fluid from COX-2−/− mice above wild-type or COX-1−/− mice. These findings indicate that the COX-2 enzyme is protective against pulmonary fibrogenesis, and we suggest that COX-2 generation of PGE2 is an important factor in resolving inflammation.

Prostaglandins (PG) are important mediators of normal tissue homeostasis, yet their aberrant production may be linked to the pathobiology of a variety of inflammatory diseases. Two distinct enzymes termed cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 and COX-2 are encoded by genes (Pghs-1 and Pghs-2) located on different chromosomes. COX-1 and COX-2 convert arachidonic acid (AA) to PGH2, which is acted on by various prostaglandin synthases to give rise to the individual bioactive PG species. 1 COX-1 is constitutively expressed in a variety of tissues including the lung. COX-2 is also constitutively expressed in lung, but is highly inducible and up-regulated by several proinflammatory cytokines. 1,2 While the role of COX-1 in inflammation is largely unknown, COX-2 appears to play a role in the inflammatory process and has been implicated as a mediator of various inflammatory diseases.

Pulmonary fibrosis is a disease characterized by the proliferation of lung fibroblasts and subsequent collagen deposition by these cells. COX-2 has been implicated as a potentially important mediator in the fibrogenic process. Cultured lung fibroblasts isolated from patients with pulmonary fibrosis have a diminished capacity to express COX-2 and these fibrotic fibroblasts synthesize less PGE2. 3,4 We previously showed that platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-induced proliferation of lung myofibroblasts was inhibited by PGE2, and this was due in part to PGE2-stimulated down-regulation of the PDGF α-receptor subtype. 5 PGE2 has also been reported to inhibit transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)-stimulated increases in α1-collagen and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) mRNAs. 6,7 Accordingly, PGE2 has been described as an anti-fibrotic factor. Nevertheless, the relative importance of COX-2 and PGE2 to the progression of pulmonary fibrosis has not been clearly established.

Mice with disrupted Pghs-1 or Pghs-2 genes have been generated using gene-targeting strategies, 8,9 and the characteristics of these mice have been reviewed. 10 COX-1-deficient (COX-1−/−) mice exhibit reduced AA-induced ear inflammation, whereas COX-2−/− mice had normal inflammatory responses to AA. 8,9 Recently, Gavett and co-workers 2 investigated the allergic lung responses in COX-1−/− and COX-2−/− mice following ovalbumin challenge. They reported that allergen-induced pulmonary inflammation and airway hyper-responsiveness were greater in COX-deficient mice compared to wild-type (WT) mice, although the COX-1−/− mice had a greater inflammatory response than COX-2−/− mice.

In this study, we investigated the inflammatory and fibrotic responses of COX-deficient mice following a single intratracheal instillation of vanadium pentoxide (V2O5), a transition metal released from the industrial burning of fuel oil that causes bronchitis and airway remodeling in humans and rats. 11,12 In wild-type mice, V2O5 caused a lung inflammatory response that resolved within days after exposure. COX-1−/− mice also resolved lung inflammation following V2O5 exposure. In contrast, COX-2−/− mice did not resolve lung inflammation in response to V2O5, and fibrotic lesions developed within two weeks following exposure. PGE2 levels in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid from wild-type and COX-1−/− mice were significantly up-regulated by V2O5 exposure, whereas PGE2 in BAL fluid from COX-2−/− mice were not significantly elevated. Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) levels in the BAL fluid of V2O5-exposed COX-2−/− mice were significantly higher than in COX-1−/− or wild-type mice. These data suggest that COX-2 has important anti-inflammatory functions that protect against pulmonary fibrosis and that the susceptibility of COX-2−/− mice to lung fibrosis correlates with increased TNF-α expression.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals

All animal studies were conducted in accordance with principles and procedures outlined in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the NIEHS Animal Care and Use Committee. Pathogen-free wild-type, COX-1−/−, and COX-2−/− mice were obtained from the breeding colony at NIEHS. They were housed under identical conditions and fed NIH 31 rodent chow (Agway, St. Mary, OH) ad libitum. All mice were of a hybrid C57BL/6J × 129/Ola genetic background, intercrossed for at least twenty generations. Mice were genotyped by PCR using DNA isolated from tail pieces as described. 8,9

Experimental Design for Intratracheal Instillation of V2O5

Male and female mice, 6 to 8 months old, weighing 20 to 35 g, were used. Within each experimental group, the sex ratio was approximately equal. V2O5 suspensions (10 mg/ml) were vortexed thoroughly, then sonicated for 30 minutes at 25°C before instillation. Mice were instilled with 50 μl of saline alone or 1 mg/kg V2O5 in saline. 13 At days 1, 3, 6, or 15 days following instillation, the lungs were lavaged for collection of BAL fluid as described below, then removed en bloc and inflated with formalin for histopathology. In some experiments, the left lung was ligated and removed for hydroxyproline assay or COX immunoblotting as described below.

Lung Histopathology

Evaluation of histopathology was done on lungs that were not lavaged. Lungs were perfusion fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin, processed routinely, and embedded in paraffin. Serial sections (5–6 μm) were stained with either hematoxylin and eosin or Masson’s trichrome. The histopathology scoring system was based on the quantitative method previously published by Cherniack and co-workers. 14 Using this system, scales ranging from 0 to 5 were used to describe the two different components of the pathological process. The parameter defined as q expressed the numbers of different types of inflammatory cells (polymorphonuclear cells, lymphocytes, eosinophils, monocytes/macrophages, and multinucleated giant cells) infiltrating the alveoli. The evaluation was based on the following arbitrary grades of severity: 0 = no inflammatory cell infiltration; 1 = 1–2 cells per alveolus; 2 = 3–4 cells per alveolus; 3 = 5–8 cells per alveolus; 4 = 9–11 cells per alveolus; 5 = more than 12 cells per alveolus.

The parameter defined as a expressed the proportion, or relative area, of the lung tissue showing inflammation and included these grades: 0 = no damage detected; 1 = 1–3% of total lung area; 2 = 4–15% of total lung area; 3 = 16–40% of total lung area; 4 = 41–75% of total lung area; 5 = 76–100% of total lung area.

The scoring was done by blind evaluation without knowing the genotype or treatment.

Hydroxyproline Assay

The procedure for quantitation of lung hydroxyproline has been described elsewhere. 15 Whole lung tissue was washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and hydrolyzed for 18 hours in 6N HCl at 110°C (∼40 ml/6 g of tissue). 1 drop of 1% phenolphthalein in ethanol was added to each sample and the pH adjusted to 6.0 with NaOH titration. Two ml from each sample was centrifuged 5 minutes at 1500 rpm and the pellet oxidized with 1 ml of 0.6 mol/L Chloramine-T for 30 minutes. Each sample then received 1 ml of 7.5% p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde and was incubated at 65°C for 15 minutes. The absorbance was measured at 560 nm on a spectrophotometer. Lung hyroxyproline was quantitated against a standard curve set up with purified hydroxyproline (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and values were corrected for total lung wet weight.

Western Blotting

Analysis of COX-1 and COX-2 protein levels in lung homogenates was performed by Western blot analysis as described previously. 2 Whole lung lysates were prepared from frozen lung tissues by homogenization in a buffer containing 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1% Triton X-100, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EGTA, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mmol/L NaF, 0.25 mol/L PMSF, 1 mg/ml leupeptin, 1 mg/ml aprotinin, 1 mg/ml pepstatin, and 100 mmol/L Na3VO4. Goat anti-mouse COX-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) and rabbit anti-mouse COX-2 (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI) were specific for their respective COX isoforms and used according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Recombinant COX-1 and COX-2 protein standards were prepared as described by Chulada et al and were used to confirm that anti-COX-1 only recognized recombinant COX-1 and anti-COX-2 only recognized recombinant COX-2. 16 For immunoblotting, proteins were resolved by electrophoresis in 10% SDS (w/v) polyacrylamide gels (Novex, San Diego, CA) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were immunoblotted using the primary COX-1 or COX-2 antibodies (1:1000 dilution) and then either goat anti-rabbit or rabbit anti-goat IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:2000 dilution) (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA). Western blots were developed using the ECL Western Blotting Detection System (Amersham International, Buckinghamshire, UK). Densitometry of the COX-1 and COX-2 protein bands was performed using the NIH Image Program (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded lung tissue. Six-μm lung sections were de-paraffinized with xylene, progressively re-hydrated in decreasing percentages of ethanol, and immersed in 3% hydrogen peroxide to degrade any endogenous peroxidases. Antigen sites were retrieved by heating the sections on slides in 0.01 mol/L sodium citrate in a microwave oven and cooling for 20 minutes to room temperature. Sections were placed in a humidity chamber and incubated in a blocking solution (anti-goat IgG, Vectastain Elite Kit) for 1 hour at room temperature. All antibodies described here after were diluted in 1X automation buffer (Biomeda Corp., Foster City, CA) containing 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma). Sections were incubated overnight with primary antibody (rabbit anti-mouse COX-2 polyclonal antibody, 1:5000, or rabbit anti-mouse COX-1 polyclonal antibody, Cayman Chemical). A streptavidin-biotin affinity system (Vectastain Elite ABC Kit, Rabbit IgG, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was used as the detection system. Tissues were incubated with biotinylated secondary rabbit IgG at room temperature for 30 minutes, washed three times with 1X automation buffer and incubated with ABC complex for 30 minutes. COX-1 or COX-2 were visualized by the addition of 3,3′-diaminobenzidine for 5 minutes. Tissues were counterstained with hematoxylin. Immunohistochemistry was also used to verify cell types staining for COX-1 or COX-2. Type 2 cells were identified using a goat anti-SP-A (surfactant protein A, C-20) polyclonal antibody at a dilution of 1:10 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Clara cells were identified using a goat anti-CC10 (Clara cell 10 kd protein, T-18) polyclonal antibody at a dilution of 1:50 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and macrophages were identified with a rat anti-mouse antibody against F4/80 (a 160-kd glycoprotein expressed by murine macrophages) at a dilution of 1:50 (Serotec, Raleigh, NC). The methodology for detection of cell-specific markers was essentially the same as that for COX-1 and COX-2 immunostaining, except the secondary antibodies used for SP-A and CC10 immunostaining was donkey anti-goat IgG at a dilution of 1:500 (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA), and the secondary antibody used for F4/80 immunostaining was goat anti-rat IgG (Serotec).

Collection of Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid and Immunoassays for Prostanoids and Cytokines

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid was collected from wild-type and COX null lungs at 1, 3, 6, and 15 days postinstillation. Lungs were lavaged with three 1-ml aliquots of sterile saline. Approximately 90% of the total injected volume was consistently recovered. The BAL fluid was placed on ice and centrifuged at 360 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. BAL cells were resuspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and counted using a hemocytometer. An aliquot of the suspension was taken for preparation of differential slides of BAL cells (Cytospin 3, Shandon, Pittsburgh, PA), which were then stained with Leuko-Stat (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), and differentiated using conventional morphological criteria for macrophages/monocytes, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils. Aliquots of BAL fluid were assayed for prostanoids (PGE2, PGD2, and LTB4) by enzyme immunoassay (Cayman Chemical Co.), or assayed for cytokines using commercially available ELISA kits (TNF-α, interleukin (IL)-8, TGF-β1, PDGF-BB, IL-13). TNF-α ELISA was purchased from Endogen, Inc. (Woburn, MA). All other ELISA kits were purchased from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Statistical Analysis

All values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Data were analyzed by analysis of variance using SYSTAT software (SYSTAT Inc., Evanston, IL). When F values indicated that a significant difference was present, Fisher’s LSD test for multiple comparisons was used. Values were considered significantly different if P was less than 0.05.

Results

COX-2−/− Mice Exhibit Increased Lung Inflammatory Responses Following V2O5 Instillation

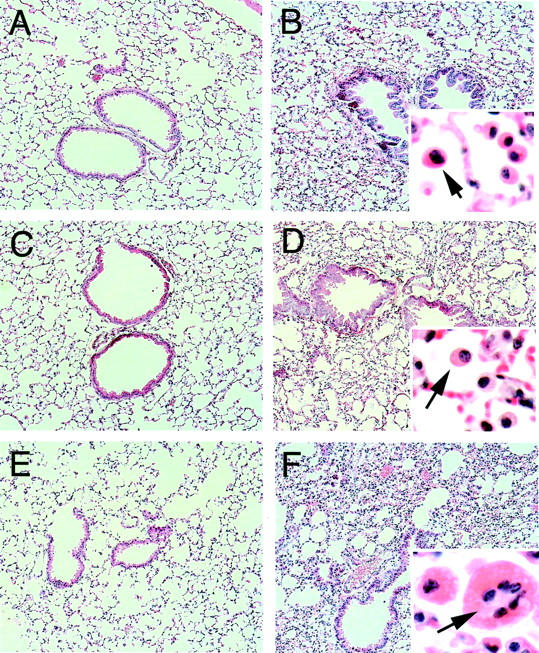

The lungs from wild-type, COX-1−/−, and COX-2−/− mice were histologically normal after saline instillation (Figure 1A, C, and E) ▶ . V2O5 instillation caused a mild inflammatory response within the lung parenchyma and peribronchiolar regions of either wild-type or COX-1−/− mice characterized primarily by the presence of mononuclear cells (Figure 1, B and D) ▶ . In contrast to wild-type and COX-1−/− mice, a marked inflammatory response was observed in the lungs of COX-2−/− mice 3 days following V2O5 exposure characterized by infiltration of mononuclear cells and multinucleated giant cells (Figure 1F) ▶ .

Figure 1.

Lung histopathology showing increased injury and inflammation in COX-2−/− mice relative to wild-type and COX-1−/− mice 3 days following intratracheal instillation of V2O5. A: Saline-instilled wild-type. B: V2O5-instilled wild-type. Inset shows mononuclear cell infiltration (arrow). C: Saline-instilled COX-1−/−. D: V2O5-instilled COX-1−/−. Arrow in inset indicates mononuclear cell. E: Saline-instilled COX-2−/−. F: V2O5-instilled COX-2−/−. Arrow in inset indicates multinucleated giant cell amid numerous mononuclear cells. All sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Magnification, ×80, except for insets which are ×400.

A histopathological examination of the formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded lung sections from wild-type and COX null mice was performed in a blinded fashion. This evaluation showed that the majority of inflammatory cells occupying the alveolar spaces following V2O5 exposure were mononuclear cells, with the remaining cells identified as neutrophils (Table 1) ▶ . A small but consistent number of multinucleated giant cells were observed in COX-2−/− mice 3 days after V2O5 exposure (Figure 1F ▶ , Table 1 ▶ ). In wild-type mice and COX-1−/− mice, V2O5 instillation caused as much as a twofold increase in the overall histopathology score, which accounted for all of the parameters shown in Table 1 ▶ . V2O5 instillation caused a three- to fourfold increase in the inflammatory score in COX-2−/− mice.

Table 1.

Lung Inflammatory Scores in Saline- and V2O5-Instilled WT, COX-1−/−, and COX-2−/− Mice

| Lesion | Saline | V2O5 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT (4) | COX-1−/− (5) | COX-2−/− (6) | WT (7) | COX-1−/− (5) | COX-2−/− (6) | |

| PMN leukocytes | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.85 ± 0.49* | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 1.16 ± 0.40* |

| Mononuclear cells | 1.25 ± 0.25 | 1.60 ± 0.25 | 1.60 ± 0.44 | 2.42 ± 0.46* | 1.80 ± 0.00 | 3.50 ± 0.22* |

| Multinucleated giant cells | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.14 ± 0.15 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.50 ± 0.34* |

| Total cellular score (q) | 1.25 ± 0.25 | 1.60 ± 0.25 | 1.60 ± 0.44 | 3.44 ± 0.77* | 1.80 ± 0.38 | 5.00 ± 0.69*† |

| % of alveoli affected (a) | 2.00 ± 0.41 | 1.60 ± 0.25 | 2.00 ± 0.35 | 2.57 ± 0.29 | 2.00 ± 0.32 | 5.00 ± 0.78*† |

Histopathological scoring system (0 to 5, where 5 is greatest inflammation) was based on types of inflammatory cells per alveoli (q) and % of alveoli affected in the lung tissue (a) as described in Materials and Methods. Data show the mean±SEM. Numbers in parentheses below group name indicate number of animals in that group.

*P<0.05, compared to saline control.

†P<0.05, compared to WT or COX-1−/−.

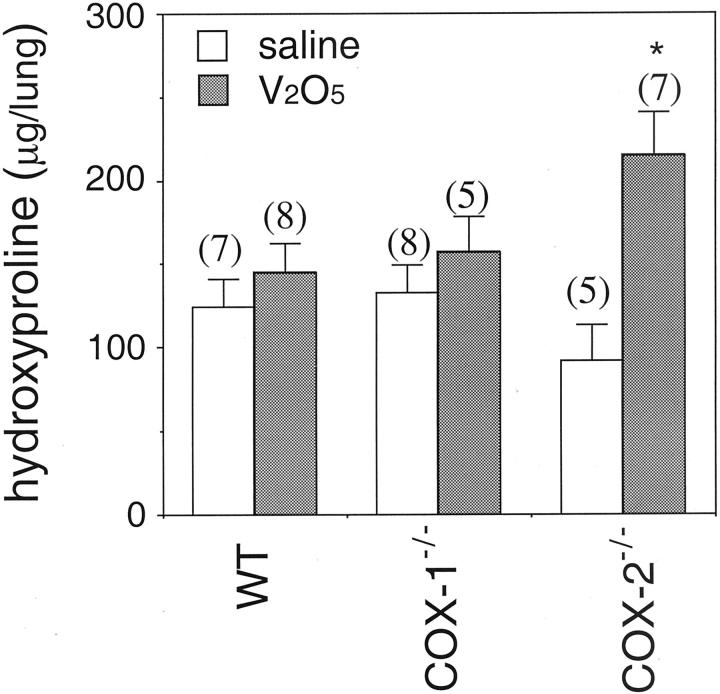

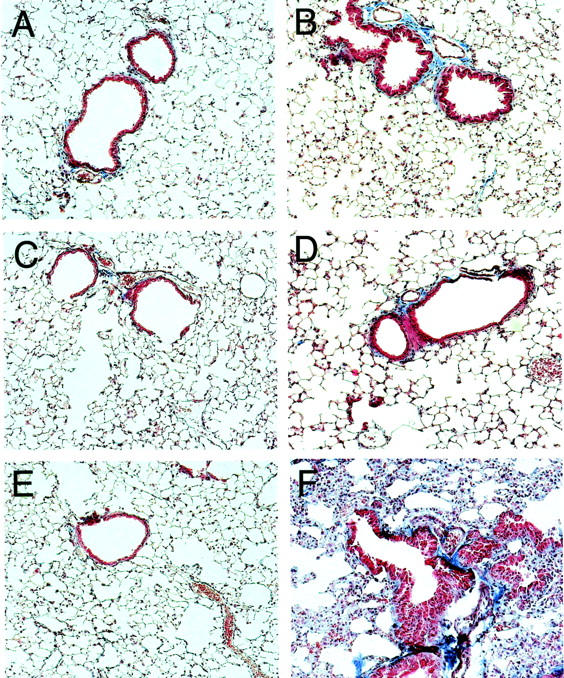

COX-2−/− Mice Develop Pulmonary Fibrotic Lesions and Have Increased Total Lung Hydroxyproline Following V2O5 Instillation

Wild-type mice and COX-1−/− mice did not develop pulmonary fibrosis within the lung parenchyma (Figure 2, A–D ▶ ). In contrast, trichome staining showed that COX-2−/− mice developed severe pulmonary fibrosis at 15 days post-V2O5 lung injury (Figure 2, E and F) ▶ . Total lung collagen was increased twofold above saline-instilled counterparts only in the COX-2−/− mice (Figure 3) ▶ .

Figure 2.

Trichrome staining of lung sections showing enhanced fibrosis in COX-2−/− mice relative to wild-type and COX-1−/− mice 15 days following intratracheal instillation of V2O5. The magnification of each panel is ×80. A: Saline-instilled wild-type. B: V2O5-instilled wild-type. C: Saline-instilled COX-1−/−. D: V2O5-instilled COX-1−/−. E: Saline-instilled COX-2−/−. F: V2O5-instilled COX-2−/−.

Figure 3.

Hydroxyproline content in lungs of wild-type, COX-1−/−, and COX-2−/− mice instilled with saline or V2O5. Lungs were harvested 15 days after instillation and digested for hydroxyproline content using the colorimetric assay described in Materials and Methods. Numbers in parentheses above each bar indicate number of animals in that group. *, P < 0.05 compared to saline.

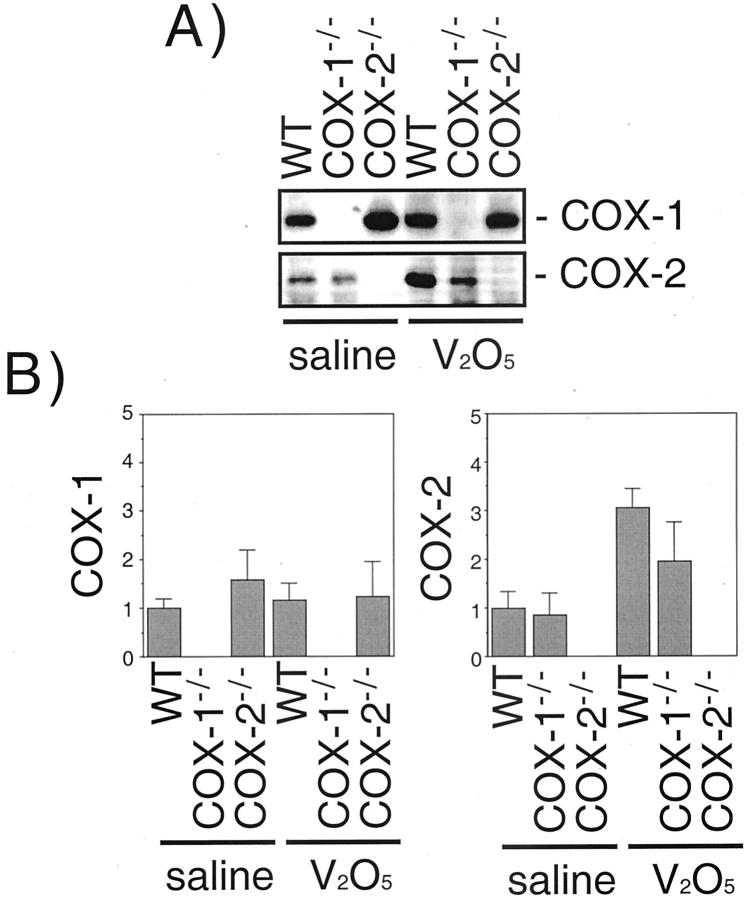

COX-2 Protein Levels Are Increased Following V2O5 Instillation, Whereas COX-1 Levels Were Not Increased

Western blot analysis of whole lung protein was performed to demonstrate a lack of the appropriate COX protein in null mice and to measure inducible COX protein at day 1 following V2O5 exposure. The specificity of COX antibodies was confirmed by using recombinant COX-1 or COX-2 proteins in Western blots (data not shown). Both COX-1 and COX-2 were detected in saline-treated wild-type mice (Figure 4) ▶ . COX-2 protein was up-regulated threefold at day 1 after V2O5 exposure in wild-type mice, and was increased about twofold by V2O5 in COX-1−/− mice. COX-1 was not increased by V2O5 in wild-type or COX-2−/− mice. COX-1 and COX-2 were not detected in COX-1−/− and COX-2−/− mice, respectively (Figure 4) ▶ .

Figure 4.

COX-1 and COX-2 protein expression 24 hours following saline and V2O5 instillation in wild-type, COX-1−/−, and COX-2−/− mice. The abundance of COX-1 and COX-2 protein in the lungs was determined by Western blotting using immunospecific antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. A: Representative Western blot. B: Scanning densitometry of COX-1 and COX-2 expression. Data are the mean ± range of two separate experiments.

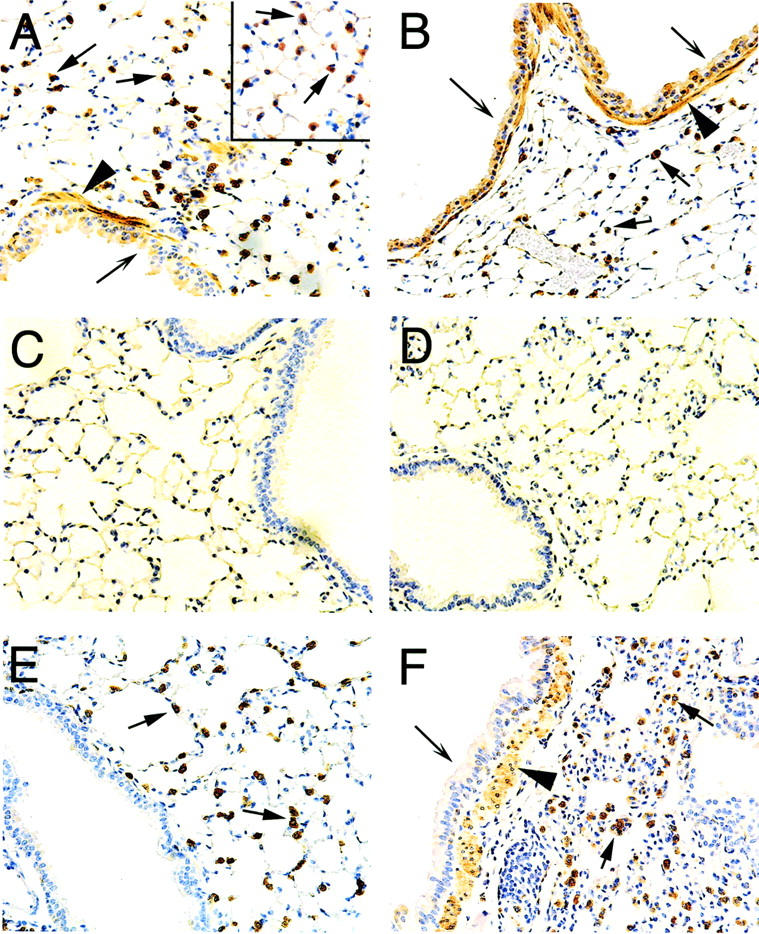

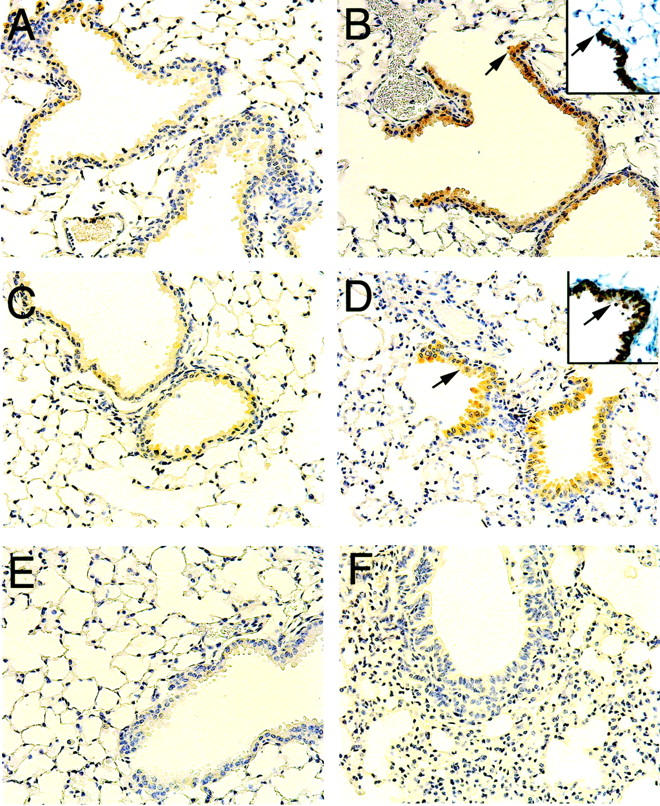

Immunohistochemical Localization of COX-1 and COX-2 Following V2O5-Induced Lung Injury

Immunohistochemistry was performed at day 1 post-V2O5 instillation to determine which cell types were expressing COX-1 and COX-2 following V2O5-induced lung injury. In both saline- and V2O5-instilled wild-type mice, abundant COX-1 immunostaining was observed in type 2 epithelial cells, airway smooth muscle cells, and bronchiolar epithelial cells (Figure 5, A and B) ▶ . The identity of type 2 cells was confirmed by immunostaining for SP-A (surfactant protein-A) (Figure 5A) ▶ . No COX-1 immunostaining was observed in saline or V2O5-instilled COX-1−/− mice (Figure 5, C and D) ▶ . Saline-instilled COX-2−/− mice had a similar pattern of COX-1 immunostaining compared to that of wild-type mice. The lungs of V2O5-exposed COX-2−/− mice exhibited COX-1 staining within early inflammatory lesions and COX-1 was localized to type 2 cells, bronchial epithelial cells, and airway smooth muscle cells (Figure 5, E and F) ▶ . In these V2O5-induced inflammatory lesions, some lung macrophages (identified by immunostaining for F4/80 antigen) contained both SP-A and COX-1 (Figure 5F) ▶ . COX-2 immunostaining was weak in saline-instilled wild-type and COX-1−/− mice and localized to Clara cells of the terminal bronchioles (Figure 6, A and C) ▶ . The identity of COX-2 positive Clara cells was confirmed by immunostaining for CC10 (Clara cell 10 kd protein) (Figure 6, B and D) ▶ . Following V2O5 instillation, intense COX-2 immunostaining was observed in Clara cells of wild-type and COX-1−/− mice (Figure 6, B and D) ▶ . No COX-2 immunostaining was observed in the lungs of COX-2−/− mice (Figure 6, E and F) ▶ .

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry showing COX-1 localization in type II epithelial cells, airway smooth muscle cells, and airway epithelium. A: Saline-instilled wild-type showing numerous COX-1 positive cells residing within the alveolar walls of the lung parenchyma (arrows); the inset panel shows the results of SP-A immunostaining that confirmed these cells as type II pneumocytes. Airway epithelial cells (barbed arrow) and airway smooth muscle cells (arrowhead) were also positive for COX-1. B: V2O5-instilled wild-type showing COX-1 localized in type II epithelial cells (arrows), airway epithelium (barbed arrows), and airway smooth muscle (arrowhead). C: Saline-instilled COX-1 null. D: V2O5-instilled COX-1 null. E: Saline-instilled COX-2 null showing COX-1 localized in type II cells (arrows) but not in Clara cells of terminal bronchiole. F: V2O5-instilled COX-2 null showing COX-1 localized in airway epithelium (barbed arrow), airway smooth muscle (arrowhead), and type II cells (arrows). Note the absence of COX-1 immunostaining in the COX-1 null mice (C and D). Magnification of all panels ×160.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemistry showing COX-2 localization in Clara cells of the distal airways and terminal bronchioles. A: Saline-instilled wild-type showing weak COX-2 immunostaining in Clara cells. B: V2O5-instilled wild-type showing increased COX-2 immunostaining in epithelial cells of terminal bronchioles that were confirmed as Clara cells by immunostaining with a CC10 antibody (inset). Arrows indicate the distal end of the terminal bronchiole in serial sections stained for COX-2 or CC10. C: Saline-instilled COX-1 null. D: V2O5-instilled COX-1 null showing increased COX-2 immunostaining in Clarac cells of terminal bronchioles (inset shows CC10 immunostaining on a serial section and arrows indicate the same bronchiole that is positive for both COX-2 and CC10). E: Saline-instilled COX-2 null. F: V2O5-instilled COX-2 null. Note the absence of COX-2 immunostaining in the COX-2 null mice. All panels ×160.

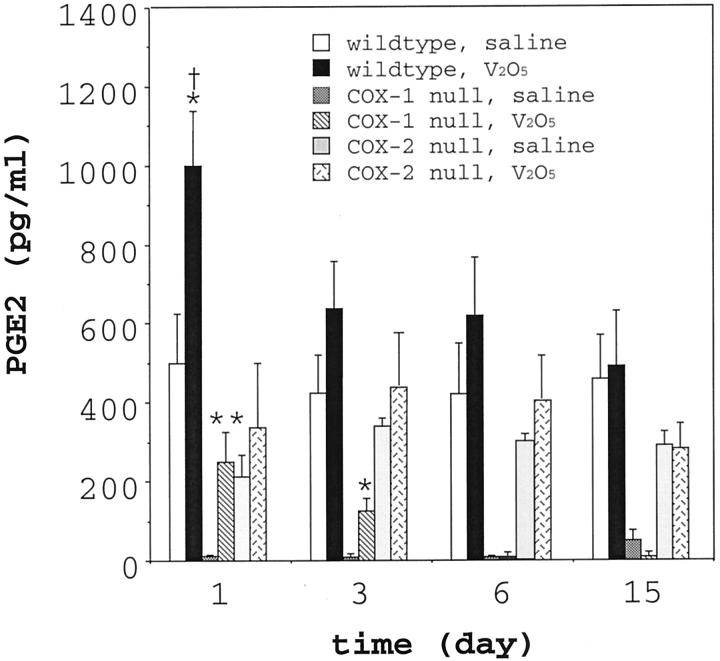

Differential Production of PGE2 in the Lungs of Wild-Type and COX-Deficient Mice Following V2O5 Instillation

BAL fluid from saline or V2O5-instilled wild-type and COX-2−/− mice was analyzed for several prostanoids (PGE2, PGD2, LTB4) to gain mechanistic insight regarding the susceptibility of COX-2−/− to the fibrotic effects of V2O5. PGD2 and LTB4 levels in BAL were increased by V2O5 instillation but were not statistically different among genotypes (data not shown). The PGE2 level in the BAL from saline-instilled wild-type mice was ∼500 pg/ml and increased approximately twofold 24 hours after V2O5 instillation (Figure 7) ▶ . However, V2O5 instillation did not cause significant increases in BAL PGE2 at days 3, 6, and 15 post-instillation. This was consistent with Western blot analyses of total lung protein that showed induction of COX-2 at 24 hours post-V2O5 instillation (Figure 4) ▶ . The PGE2 level in the BAL fluid from COX-1−/− mice was extremely low (∼10 pg/ml), yet increased 25-fold within 24 hours after V2O5 instillation. PGE2 in the BAL fluid from saline-instilled COX-2−/− mice was ∼200 pg/ml and was not significantly increased following V2O5 instillation.

Figure 7.

PGE2 levels in BAL fluid in wild-type, COX-1−/−, and COX-2−/− mice following instillation with saline or V2O5. BAL fluid was collected at the indicated time points post-instillation and PGE2 measured by an enzyme immunoassay. Each V2O5 group represents 5 to 6 animals and each saline group represents 3 to 4 animals. *, P < 0.05 vs. all saline-instilled groups. **, P < 0.01 vs. all saline-instilled groups. †, P < 0.05 vs. COX-1−/− or COX-2−/− V2O5 group.

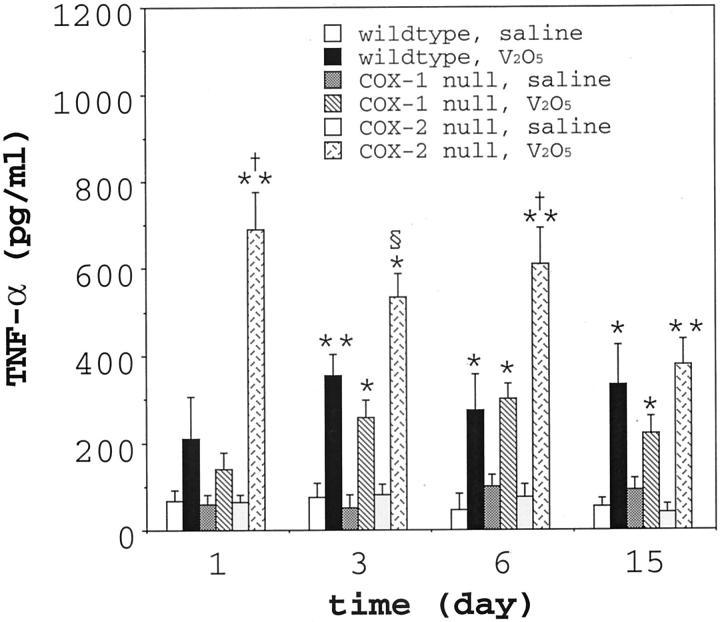

Increased Levels of TNF-α in the BAL Fluid from COX-2−/− Mice

To gain further mechanistic insight into the susceptibility of COX-2−/− mice to the fibrogenic effects of V2O5, we analyzed BAL fluid for a variety of cytokines that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of fibrosis, including IL-8, TNF-α, IL-13, PDGF-BB, and TGF-β1. IL-8 was detectable in BAL and up-regulated by V2O5 but was not significantly different among genotypes (data not shown). IL-13, PDGF-BB, and TGF-β1 were not detectable in the BAL fluid in any of the genotypes using the commercially available ELISA kits, even when the BAL fluid was acid-activated to liberate TGF-β1 from putative latent complexes. It may be that these cytokines play an important role in the pathogenesis of vanadium-induced fibrosis; however, these factors were below the detection range of the commercially available ELISAs used in this study. TNF-α was consistently detectable in the BAL fluid from all genotypes and significant differences were observed following V2O5 instillation among the various genotypes (Figure 8) ▶ . TNF-α in the BAL fluid of wild-type mice or COX-1−/− increased two to sixfold between 1 and 15 days post-instillation. However, there were no significant differences in TNF-α levels among V2O5-exposed wild-type and COX-1−/− mice. In contrast, TNF-α in the BAL fluid from V2O5 exposed COX-2−/− mice was elevated by as much as 10-fold above saline controls, and these levels were significantly higher than either wild-type or COX-1−/− at days 1, 3, and 6 post-V2O5 instillation. However, by day 15, there were no significant differences in TNF-α levels among genotypes in the V2O5-instilled groups.

Figure 8.

TNF-α levels in BAL fluid in wild-type, COX-1−/− and COX-2−/− mice following instillation with saline or V2O5. BAL fluid was collected at the indicated time points post-instillation and TNF-α was measured by ELISA. Each V2O5 group represents 5 to 6 animals and each saline group represents 3 to 4 animals. *P < 0.05 vs. all saline-instilled groups. **, P < 0.01 vs. all saline-instilled groups. §, P < 0.05 vs. wild-type V2O5 group. †, P < 0.01 vs. wild-type V2O5 group.

Discussion

A variety of studies have implicated COX enzymes and their eicosanoid products in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. However, to date no studies have established a definitive role for either COX-1 or COX-2 enzymes during lung fibrogenesis. Our investigation has revealed a central role for the COX-2 enzyme in protecting the lung against fibrosis. V2O5 exposure caused a significantly higher inflammatory score in COX-2−/− mice as compared to COX-1−/− or wild-type mice. COX-2−/−mice subsequently developed pulmonary fibrosis within the lung parenchyma and a significant increase in total lung hydroxyproline, whereas COX-1−/− and wild-type did not. These observations suggest that eicosanoid products of the COX-2 enzyme mediate a protective effect in the development and/or resolution of inflammation. Other studies have reported increased inflammatory responses following ovalbumin challenge to the lung 2 or following acute colonic injury 17 in both COX-1−/− and COX-2−/− mice. On the other hand, Zeldin et al 18 recently reported that LPS-induced inflammatory responses were not increased in COX-1−/− or COX-2−/− mice compared to wild-type mice. Thus, COX enzymes appear to be important to the development of fibrosis and inflammation in response to certain stimuli, yet COX enzymes may not be required for the development of LPS-induced inflammation.

PGE2 is a major eicosanoid product of both COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes, 19 and has been proposed as an anti-fibrotic mediator in the lung. 3,6,20 We previously reported that PGE2 suppresses PDGF-stimulated growth of rat pulmonary myofibroblasts in part by down-regulating the PDGF α receptor subunit. 5 Other investigators have shown that fibroblasts from patients with lung fibrosis have a diminished capacity to produce PGE2. 3,4 Moreover, Ogushi and co-workers reported that PGE2 synthesis was decreased in lung fibroblasts isolated from rats with bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. 20 Thus, there is abundant evidence to support the idea that PGE2 is an anti-fibrotic mediator.

In the present study, PGE2 levels were significantly increased early after V2O5 exposure (24 hours) in both wild-type and COX-1−/− mice, whereas PGE2 levels in COX-2−/− mice were not significantly increased at any time point (Figure 7) ▶ . Both COX-1−/− and COX-2−/− mice had diminished PGE2 levels in their BAL fluid compared to wild-type mice 24 hours following V2O5 exposure. BAL fluid from COX-1−/− mice contained by far the lowest concentrations of PGE2 (∼10 pg/ml) although V2O5 exposure elevated the PGE2 level 25-fold above the saline-instilled group. In contrast, PGE2 levels in the BAL fluid from COX-2−/− mice were not significantly increased at any time point post-V2O5 instillation compared to the saline-instilled group. These data suggest that the increase in PGE2, rather than differences in the absolute level of PGE2 among genotypes, may be a significant factor in protecting the lung from an inflammatory response. An alternative hypothesis is that other AA metabolites, including cyclopentanones such as PGD2 or leukotrienes such as LTB4, might be differentially induced among these genotype following V2O5 exposure. However, while V2O5 increased PGD2 or LTB4 in BAL fluid by as much as twofold, we observed no significant differences in these mediators among wild-type, COX-1−/−, or COX-2−/− mice.

Our findings suggest that TNF-α could role in susceptibility of the COX-2−/− mice to pulmonary fibrosis. COX-2−/− mice had significantly higher levels of TNF-α in BAL fluid after V2O5 exposure (∼10-fold increase above saline controls) compared to wild-type or COX-1−/− groups (three- to sixfold increases above saline controls) (Figure 8) ▶ . TNF-α has been implicated as a central mediator in the progression of pulmonary fibrosis. For example, Piguet and co-workers 21 reported that neutralizing antibodies against TNF-α block silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Sime and colleagues 22 demonstrated that over-expression of TNF-α in rat lung through adenoviral transfer of a TNF-α cDNA caused severe pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis with induction of transforming growth factor-β1. Moreover, the spontaneous development of pulmonary fibrosis in viable motheaten mutant mice has been associated with increased TNF-α in the lung and serum. 23 Finally, TNF-α receptor knockout mice are protected from pulmonary fibrosis induced by asbestos inhalation. 24 Thus, several different experimental strategies have been used to demonstrate a role for TNF-α in mediating pulmonary fibrosis.

Enhancement of the early inflammatory events (ie, within 24 hours) appear to be critical to the development of lung fibrosis in COX-2−/− mice. In particular, the increased expression of TNF-α in the lungs of V2O5-exposed COX-2−/− mice above their wild-type or COX-1−/− counterparts suggests that products of the COX-2 enzyme are important in regulating TNF-α protein levels. Alternatively, it is possible that increased TNF-α is a consequence of COX-2-deficient mice not being able to resolve inflammation and that the increased TNF-α is simply due to the persistent increased burden of inflammatory cells. Nevertheless, V2O5 exposure caused significant increases in PGE2 above saline-exposed mice in both the wild-type and COX-1−/− groups at 24 hours post-instillation, but V2O5 exposure caused no significant increases in PGE2 in the BAL fluid of COX-2−/− mice (Figure 7) ▶ . While TNF-α increases PGE2 synthesis by inducing COX-2 expression, 25 PGE2 has been shown to suppress TNF-α production in a variety of different cell types. 26 The constitutive levels of PGE2 in the BAL fluid from COX-1−/− mice were extremely low compared PGE2 levels in the BAL fluid from wild-type or COX-2−/− mice, yet PGE2 levels in the COX-1−/− mice were markedly elevated by V2O5 instillation. Therefore, we propose that the induction of PGE2 synthesis, rather than the absolute concentrations of PGE2, may more important in suppressing TNF-α production in the lung. Suppression of TNF-α via COX-2 expression would require an intracellular “sensor” that could be turned on or turned off to initiate a negative feedback loop to suppress TNF-α synthesis. Indeed, PGE2 has been reported to suppress NFκB, 27 a transcription factor that has been reported to mediate vanadium-induced TNF-α expression. 28 While our data show a correlation between lack of induction of PGE2 synthesis and increased TNF-α in COX-2−/− mice, it remains unclear whether or not the inability to up-regulate PGE2 synthesis is causally related to increased TNF-α production. Future research should address this important issue.

Our immunohistochemical staining of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded lung sections showed strong expression of COX-1 within type 2 epithelial cells, bronchial epithelial cells, and airway smooth muscle cells (Figure 6) ▶ . The identity of type 2 cells was verified by SP-A immunostaining, which clearly demonstrated these cells as the COX-1-positve cell type in the lung parenchyma. However, in V2O5-exposed COX-2−/− mice wherein a severe inflammatory response ensued, some F4/80 antigen-positive macrophages also possessed immunostaining for both SP-A and COX-1. It is likely that the phagocytosis of apoptotic type 2 cells by macrophages resulted in COX-1 immunostaining, although we cannot rule out that some macrophages may express endogenous COX-1. COX-1 was expressed in both saline and V2O5-instilled wild-type and COX-2−/− mice. These data agree with Western blot analysis of whole lung protein that indicated equal expression of COX-1 in the lungs of saline or V2O5-exposed wild-type or COX-2−/− mice, but no expression in COX-1−/− mice (Figure 4) ▶ . In contrast, COX-2 was almost exclusively localized in Clara cells of the terminal bronchioles of wild-type and COX-1−/− mice, and was strongly induced 24 hours following V2O5 exposure (Figure 6) ▶ . These data were consistent with Western blot analysis of whole lung protein that showed COX-2 in the lungs of wild-type or COX-1−/− mice that was up-regulated by V2O5 exposure (Figure 4) ▶ . Further studies should focus on the significance of the differential localization of COX-1 and COX-2 in these lung cell types.

V2O5 was used as a fibrotic agent in the present study rather than more conventional fibrotic stimuli, such as bleomycin. We previously reported that V2O5 causes lung inflammation and fibrosis in rats, yet the inflammatory response largely resolves within 2 weeks. 12,13 We initially postulated that either COX-1 or COX-2 null mice might be susceptible to fibrotic agents, and therefore selected V2O5 as a relatively mild fibrotic agent. Surprisingly, the C57BL/6J × 129/Ola wild-type mice were quite resistant to V2O5-induced injury as compared to Sprague-Dawley rats that were used in our earlier studies. 13 As a result, V2O5-induced inflammatory lung lesions resolved in these wild-type mice. Compared with V2O5, the intratracheal instillation of bleomycin causes relatively prolonged inflammation that develops into a robust fibrotic response in rats and mice. Keerthisingam and colleagues 29 recently presented pathological evidence of enhanced lung fibrosis in COX-2−/− mice 2 weeks following the intratracheal instillation of bleomycin sulfate. While that was the first study to report enhanced lung fibrogenesis in COX-2−/− mice, the authors did not measure inflammatory mediators or provide evidence for a mechanism of COX-2−/−susceptibility to bleomycin-induced fibrosis. However, it is interesting that COX-2−/− mice are susceptible to the fibrogenic effects of a chemotherapeutic drug (bleomycin) as well as a transition metal (V2O5). This indicates that the susceptibility of COX-2−/− mice is a general response to diverse fibrogenic stimuli.

COX-2 may also have a protective role in other inflammatory lung diseases. Gavett and co-workers recently reported that COX-2−/− mice have an increased allergic and inflammatory response to ovalbumin challenge compared to WT mice, yet the COX-2−/− mice have approximately the same BAL level of PGE2 as WT. 2 Peebles and colleagues demonstrated that mice treated with the COX inhibitor indomethacin had increased production of interleukin-5 and interleukin-13 following ovalbumin challenge. 30 Both of these Th-2 cytokines have been implicated in the development of airway inflammation in asthma. 31 Mice pre-treated with indomethacin also showed increased airway hyperresponsiveness to ovalbumin challenge. Collectively, these studies suggest that COX-1 and/or COX-2 products may be involved in the development of allergic airway inflammation.

In summary, we report that COX-2−/− mice are susceptible to the development of pulmonary fibrosis following exposure to the transition metal, V2O5. In contrast, COX-1−/− mice were not susceptible to the fibrogenic effects of vanadium and their lung inflammatory response resolved. Vanadium-induced lung injury increased the level of PGE2 in BAL fluid from WT and COX-1−/− mice, but did not cause a significant increase in the level of PGE2 in the BAL fluid from COX-2−/− mice. The level of TNF-α in the BAL fluid of vanadium-exposed COX-2−/− mice was significantly higher than in vanadium-exposed COX-1−/− or wild-type mice. These data indicate that COX-2 is protective against pulmonary fibrosis and we suggest that increased expression of TNF-α caused by disruption of the Pghs-2 gene could impair resolution of inflammation and result in a fibrotic outcome.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the technical expertise of Herman Price for help in performing mouse intratracheal instillations. These studies were conducted at the NIEHS Inhalation Facility, under contract to Mantech Environmental Technology, Inc. We thank Dr. Micheal Waalkes and Dr. John Roberts at the NIEHS for helpful comments during the preparation of this manuscript. Special thanks to Julie Foley for interpretation of CC-10 and SP-A immunohistochemical staining.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to James C. Bonner, Ph.D., Laboratory of Pulmonary Pathobiology, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, P.O. Box 12233, Research Triangle Park, NC 27709. E-mail: bonnerj@niehs.nih.gov.

References

- 1.Smith WL, Dewitt DL: Prostaglandin endoperoxidase H synthases-1 and -2. Adv Immunol 1996, 62:167-215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gavett SH, Madison SL, Scarborough PE, Qu W, Boyle JE, Chulada PC, Tiano HF, Lee CA, Langenbach R, Roggli VL, Zeldin DC: Allergic lung responses are increased in prostaglandin H synthase-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 1999, 104:721-732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilborn J, Crofford LJ, Burdick MD, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM, Peters-Golden M: Cultured lung fibroblasts isolated from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis have a diminished capacity to synthesize prostaglandin E2 and to express cyclooxygenase-2. J Clin Invest 1995, 95:1861-1868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vancheri C, Sortino MA, Tomaselli V, Mastruzzo C, Condorelli F, Bellistri G, Pistorio MP, Canonico PL, Crimi N: Different expression of TNF-α receptors and prostaglandin-E2 production in normal and fibrotic lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2000, 22:628-634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyle JE, Lindroos PM, Rice AB, Zhang L, Zeldin DC, Bonner JC: Prostaglanin-E2 counteracts interleukin-1β-stimulated up-regulation of platelet-derived growth factor α-receptor on rat pulmonary myofibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1999, 20:433-440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fine A, Goldstein RH: The effect of PGE2 on the activation of lung fibroblasts. Prostaglandins 1987, 33:903-913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ricupero DA, Rishikof DC, Kuang P-P, Poliks CF, Goldstein RH: Regulation of connective tissue growth factor expression by prostaglandin E2. Am J Physiol 1999, 277:L1165-L1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langenbach R, Morham SG, Tiano HF, Loftin CD, Ghanayem BI, Chulada PC, Mahler JF, Lee CA, Goulding EH, Kluckman KD, Sim HS, Smithies O: Prostaglandin synthase 1 gene disruption in mice reduces arachidonic acid-induced inflammation and indomethacin-induced gastric ulceration. Cell 1995, 83:483-492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morham SG, Langenbach RL, Loftin CD, Tiano HF, Vouloumanos N, Jennette JC, Mahler JF, Kluckman KD, Ledford A, Lee CA, Smithies O: Prostaglandin synthase 2 gene disruption causes severe renal pathology in the mouse. Cell 1995, 83:473-482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langenbach R, Loftin C, Lee C, Tiano H: Cyclooxygenase knockout mice: models for elucidating isoform specific functions. Biochem Pharmacol 1999, 15:1237-1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levy BS, Hoffman L, Gottsegen S: Boilermaker’s bronchitis: respiratory tract irritation associated with vanadium pentoxide exposure during oil-to-coal conversion of a power plant. J Occup Med 1984, 26:567-570 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonner JC, Rice AB, Moomaw CR, Morgan DL: Airway fibrosis in rats induced by vanadium pentoxide. Am J Physiol 2000, 278:L209-L216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonner JC, Lindroos PM, Rice AB, Moomaw CR, Morgan DL: Induction of PDGF receptor-α in rat myofibroblasts during pulmonary fibrogenesis in vivo. Am J Physiol 1998, 274:L72-L80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherniack RM, Colby TV, Flint A, Thurlbeck WN, Waldron J, Ackerson L, King TE, Jr: Quantitative assessment of lung pathology in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991, 144:892-900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rice AB, Moomaw CR, Morgan DL, Bonner JC: Specific inhibitors of platelet-derived growth factor or epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase reduce pulmonary fibrosis in rats. Am J Pathol 1999, 155:213-221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chulada PC, Loftin CD, Winn VD, Young DA, Tiano HF, Eling TE, Langenbach R: Relative activities of retrovirally expressed murine prostaglandin synthase-1 and -2 depend on source of arachidonic acid. Arch Biochem Biophys 1996, 330:301-313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morteau O, Morham SG, Sellon R, Dieleman LA, Langenbach R, Smithies O, Sartor RB: Impaired mucosal defense to acute colonic injury in mice lacking cyclooxygenase-1 or cyclooxygenase-2. J Clin Invest 2000, 105:469-478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeldin DC, Wohlford-Lenane C, Chulada P, Bradbury JA, Scarborough PE, Roggli V, Langenbach R, Schwartz DA: Airway inflammation and responsiveness in prostaglandin H synthase-deficient mice exposed to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2001, 25:457-465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brock TG, McNish RW, Peters-Golden M: Arachidonic acid is preferentially metabolized by cyclooxygenase-2 to prostacyclin and prostaglandin-E2. J Biol Chem 1999, 274:11660-11666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogushi F, Endo T, Tani K, Asada K, Kawano T, Tada H, Maniwa K, Sone S: Decreased prostaglandin E2 synthesis by lung fibroblasts isolated from rats with bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Int J Exp Pathol 1999, 80:41-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piguet PF, Collart MA, Grau GE, Sappino A-P, Vassalli P: Requirement of tumour necrosis factor for development of silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Nature 1990, 344:245-247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sime PJ, Marr RA, Gauldie D, Xing Z, Hewlett BR, Graham FL, Gauldie J: Transfer of tumor necrosis factor-α to rat lung induces severe pulmonary inflammation and patchy interstitial fibrogenesis with induction of transforming growth factor-β1 and myofibroblasts. Am J Pathol 1998, 153:825-832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thrall RS, Vogel SN, Evans R, Shultz LD: Role of tumor necrosis factor-α in the spontaneous development of pulmonary fibrosis in viable motheaten mutant mice. Am J Pathol 1997, 151:1303-1310 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu J-Y, Brass DM, Hoyle GW, Brody AR: TNF-α receptor knockout mice are protected from the fibroproliferative effects of inhaled asbestos fibers. Am J Pathol 1998, 153:1839-1847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fournier T, Fadok V, Henson PM: Tumor necrosis factor-α inversely regulates prostaglandin D2 and prostaglandin E2 production in murine macrophages. J Biol Chem 1997, 272:31065-31072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rola-Pleszczynski M, Thivierge M, Gagnon N, Lacasse C, Stankova J: Differential regulation of cytokine and cytokine receptors by PAF, LTB4, and PGE2 J Lipid Med 1993, 6:175-181 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D’Acquisto F, Sautebin L, Iuvone T, Di Rosa M, Carnuccio R: Prostaglandins prevent inducible nitric oxide synthase protein expression by inhibiting nuclear factor-κB activation in J774 macrophages. FEBS Lett 1998, 27:76-80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ye J, Ding M, Zhang X, Rojanasakul Y, Nedospasov S, Vallyathan V, Castranova V, Shi X: Induction of TNF-α in macrophages by vanadate is dependent on activation of transcription factor NF-κB and free radical reactions. Mol Cell Biochem 1999, 198:193-200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keerthisingam CB, Jenkins RG, Harrison NK, Hernandez-Rodriquez NA, Booth H, Laurent GJ, Hart SL, Foster ML, McAnulty RJ: Cyclooxygenase-2 deficiency results in a loss of the anti-proliferative response to transforming growth factor-β in human fibrotic lung fibroblasts and promotes bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am J Pathol 2001, 158:1411-1422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peebles RS, Jr, Dworski R, Collins RD, Jarzecka K, Mitchell DB, Graham BS, Sheller JR: Cyclooxygenase inhibition increases interleukin-5 and interleukin-13 production and airway hyper-responsiveness in allergic mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000, 162:676-681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wills-Karp M, Luyimbazi J, Xu X, Schofield B, Neben TY, Karp CL, Donaldson DD: Interleukin-13: central mediator of allergic asthma. Science 1998, 282:2258-2261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]