Abstract

During progression of chronic renal disease, qualitative and quantitative changes in the composition of tubular basement membranes (TBMs) and interstitial matrix occur. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1-mediated activation of tubular epithelial cells (TECs) is speculated to be a key contributor to the progression of tubulointerstitial fibrosis. To further understand the pathogenesis associated with renal fibrosis, we developed an in vitro Boyden chamber system using renal basement membranes that partially mimics in vivo conditions of TECs during health and disease. Direct stimulation of TECs with TGF-β1/epithelial growth factor results in an increased migratory capacity across bovine TBM preparations. This is associated with increased matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) production, namely MMP-2 and MMP-9. Indirect chemotactic stimulation by TGF-β1/EGF or collagen type I was insufficient in inducing migration of untreated TECs across bovine TBM preparation, suggesting that basement membrane integrity and composition play an important role in protecting TECs from interstitial fibrotic stimuli. Additionally, neutralization of MMPs by COL-3 inhibitor dramatically decreases the capacity of TGF-β1-stimulated TECs to migrate through bovine TBM preparation. Collectively, these results demonstrate that basement membrane structure, integrity, and composition play an important role in determining interstitial influences on TECs and subsequent impact on potential aberrant cell-matrix interactions.

Renal fibrosis is the common pathway of chronic renal disease progressing to end-stage renal failure. 1-3 Renal fibrosis is characterized by qualitative and quantitative changes in the composition of tubular basement membranes (TBMs), interstitial matrix, tubular atrophy, and the accumulation of myofibroblasts. 1,3-9

TBM is an important structural component of renal tubules. 7 Tubular epithelial cells (TECs) interact via their basal side with the TBM, which clearly separate the tubular compartment from the interstitial compartment. 10 Basement membranes are thin layers of a specialized extracellular matrix that provide a dynamic supporting structure on which epithelial cells grow. 11-13 They are predominantly associated with cells and it has been well demonstrated that basement membranes not only provide structural support, but also influence cellular behavior such as differentiation and proliferation. 1,14-16 The major macromolecule constituents of basement membranes are type IV collagen, laminin, heparan sulfate proteoglycans, fibronectin, and entactin. 11,17,18 Type IV collagen is the major constituent of basement membranes that acts as a scaffold and hence is speculated to provide structural integrity. 19,20 In renal fibrosis, changes in composition of TBM are speculated to occur 4-9 and we have previously shown that disruption of TBM facilitates epithelial to mesenchymal transdifferentiation (EMT) in vitro, suggesting that altered interactions between TECs and TBM play an important role in the progression of tubular atrophy, a hallmark feature of renal fibrosis. 1,16 In contrast to TBM, which is a complex, organized, and assembled suprastructure, the interstitial matrix is a loosely organized, unassembled form of extracellular matrix, with a significantly different composition than TBM. 16,21,22 Interstitial matrix is predominantly composed of type I and type III collagen, fibronectin, and heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Interstitial matrix surrounds fibroblasts and potentially interacts with these cells via integrins. 10,21,22 During renal fibrosis, excessive deposition of interstitial matrix occurs, leading to a widening of the interstitial area, which may contribute to the initial proliferation of interstitial fibroblasts. 23-26

EMT is increasingly being considered as a key component of progressive renal disease. 3,27,28 Epithelial cells display an apical-basal polarity and adhere tightly to the TBM via their basal side. Alterations in the TBM can potentially lead to the acquisition of phenotypic, as well as functional properties of myofibroblasts, potentially enabling them to proliferate and migrate into the interstitial space. 15,16,29 The current paradigm for EMT during renal fibrosis postulates that TECs lose contact with adjacent cells and the TBM, and transit through the TBM into the renal interstitium. 1,16,28,30 Cytokines such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 and epithelial growth factor (EGF) have been established as inducers of phenotypic changes in TECs in vitro. 1,16,31,32 A major focus of this study was to investigate the migratory capacity of activated TECs in relation to the different microenvironments of tubular and interstitial compartments of the kidney during health and disease.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Recombinant human TGF-β1 and human EGF were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Mouse monoclonal antibody to α-smooth muscle actin that was labeled with Cy-5, rabbit polyclonal antibody to laminin, and fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled antibody to rabbit IgG were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Mouse collagen type I and type IV were obtained from Becton Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, NJ). Soluble TGF-β receptor was a generous gift from Biogen, Inc. (Cambridge, MA).

Cell Culture

Murine renal cell lines were established and cultured as previously described. 16,33,34 They were grown according to the recommended conditions: proximal TECs (MCTs) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. 35 For experiments, the medium was replaced with serum-free K-1 medium (1:1 Ham’s F12/Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 5 μg/ml transferrin, 5 μg/ml insulin, and 5 × 10−8 mol/L hydrocortisone) containing cytokines or matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitors.

Human Kidney Samples

Kidney samples from patients with end-stage renal disease due to various primary or secondary renal diseases and from patients with renal cell carcinoma were obtained on nephrectomy. A representative area of kidney sections from a 31-year-old patient with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) because of membranous glomerulonephritis (GN) (BUN, 3.7 mg/dl, and serum creatinine, 11.1 mg/dl) is illustrated in Figure 1 ▶ . These sections were immunostained for laminin and α-smooth muscle actin. Kidneys from α3(IV) collagen knockout mice were obtained before onset of disease at 4 weeks of age and at 12 weeks (with ESRD) and stained with Masson’s trichrome. Sections from these cohorts are also shown in Figure 1 ▶ .

Figure 1.

Two-compartment Boyden chamber system mimics in vivo conditions. A: Normal mouse kidney, PAS-stained. B: Schematic illustration of normal kidney representing tubuli (T), surrounded by TBM, which separates them from the interstitium that contains fibroblasts (F) and capillaries (C). C: Kidney specimen from α3 type IV collagen knockout mouse with severe tubulointerstitial fibrosis, Masson trichrome staining. D: Schematic illustration of kidney with tubulointerstitial fibrosis, a widened interstitium that contains deposited type I collagen (Col1), an increased number of fibroblasts, fibroblast-like cells, and inflammatory cells (I). E: The two-compartment Boyden chamber mimics the tubular compartment in the upper chamber and the interstitial compartment in the lower chamber, separated by a polycarbonate membrane coated with TBM. F: Direct stimulation by TGF-β1/EGF in the upper chamber or chemotactic stimulation by TGF-β1/EGF or type I collagen leads to enhanced migration in the lower chamber. G: Double staining of human kidney from a patient with membranous nephropathy for laminin (fluorescein isothiocyanate, green) and α-smooth muscle actin (Cy5, red). In areas that had basement membranes intact, α-smooth muscle actin was not detectable. H: Disruption of TBM is associated with EMT. The arrows indicate areas where tubular cells express α-smooth muscle actin around areas of TBM disruption. Original magnifications: ×200 (G); ×400 (A, C, H).

Preparation of TBM

Bovine TBM was prepared from bovine kidneys by a modification of a method described by Neilson and colleagues, 36 Zakheim and colleagues, 37 and Freytag and colleagues. 38 The cortex was scraped off from bovine kidneys, gently homogenized, and washed by low-speed centrifugation (400 × g), to remove the bulk of cellular debris. The sediment was passed through an 80-mesh stainless steel screen and tubular membranes in this filtrate were collected on a synthetic filter. The TBM was washed and then sonicated in phosphate-buffered saline and stored at −70°C until needed. During the isolation procedure, the purity of this process was periodically monitored with the use of light microscopy.

Migration Assay

To mimic in vivo microenvironment of TBM and renal interstitium, polyvinyl-pyrrolidone-free polycarbonate membranes with 8-μm pores (Neuro Probes, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) were coated with type IV collagen or RBM on the upper side (100 μg/ml) and with type I collagen on the lower side (50 μg/ml). The bottom wells of a 48-well Boyden chamber were filled with K1 medium containing supplements according to the specific experimental protocol. Wells were covered with the coated membrane sheet and 20,000 cells/well were added into the upper chamber. The Boyden chamber was incubated for 6 hours at 37°C to allow possible migration of cells through the membrane into the lower chamber. Membranes were stained with Hema3 stain according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Biochemical Sciences, Inc., Swedesboro, NJ). Cells that migrated through the membrane were tallied using a counting grid fit into an eyepiece of a phase contrast microscope. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

Immunohistochemistry

Four-μm sections of snap-frozen tissue were fixed in methanol (100%) at −20°C. Tissue was incubated with primary antibodies to α-smooth muscle actin [dilution 1:100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] and to laminin (dilution, 1:200) simultaneously for 1 hour at room temperature. Washing with PBS was followed by incubation with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled secondary antibody (dilution, 1:100 in PBS) for 1 hour. Stainings were covered with Vecta-Shield mounting medium and staining was visualized using fluorescence microscopy.

Renal Basement Membrane Digestion

Renal basement membrane digestion was performed as described previously. 39 Briefly, to collect conditioned media, 2 × 105 MCT cells were plated in 6-well plates and stimulated for 48 hours in K1 medium containing 3 ng/ml of TGF-β1 and 10 ng/ml of EGF. Control cells were incubated for 48 hours in K1 medium without additional growth factors. For direct MMP digestion studies, 1 μg of RBM was incubated with 100 ng/ml of MMP-9 or 100 ng/ml of MMP-2 in 1 ml of reaction buffer containing 2 nmol/L CaCl2, 2 mmol/L MgCl2, and 2 mmol/L ZnSO4 (Calbiochem-Novabiochen, San Diego, CA). After incubation for 5 hours at 37°C, 20 mmol/L of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid was added to chelate calcium at the end the reaction. The supernatant after centrifugation was used in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting.

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis and Western Blotting

Supernatants from cell culture experiments were concentrated 20-fold and direct digestion supernatants were concentrated onefold. Twenty-μl of concentrated medium were used per lane for sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis electrophoresis. The separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose and blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 minutes on a shaker at room temperature. After blocking, the blot paper was incubated with α1(IV) NC1 collagen antibodies in PBS containing 1% BSA. 16 Subsequently, the blot was washed thoroughly with washing buffer and incubated with a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase for 3 hours at room temperature on a shaker. The blot was again washed thoroughly and substrate (diaminobenzidine in 0.05 mol/L of phosphate buffer containing 0.01% cobalt chloride and nickel ammonium) was added and incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature. Upon completion of this step, the substrate was poured out and substrate buffer containing hydrogen peroxide was added. After development of bands, the reaction was stopped with distilled water and the blot was dried on paper towels.

Zymography

Cells (1 × 105 per well) were plated in 6-well plates and grown for 6 hours in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% fetal calf serum. The medium was replaced with K1 medium or K1 medium supplemented with 3 ng/ml of TGF-β1 and 10 ng/ml of EGF. After incubation, the medium was removed, cells were counted and the volume of medium was normalized to cell counts. Electrophoresis was performed using 20 μl of medium per lane in 10% gelatin zymogram ready-cast gels (Bio Rad, Hercules, CA). Gels were washed twice for 10 minutes at room temperature in renaturing buffer (2.5% v/v Triton X-100) and then incubated for 18 hours at 37°C in development buffer (50 mm Tris, 200 mm NaCl, 5 mm CaCl2, 0,02% v/v Brij-35). Bands were visualized by staining the gel with Coomassie blue.

Statistical Analysis

All values are expressed as mean ± SEM unless specified. Analysis of variance was used to determine statistical differences between groups using Sigma-Stat software (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA). Further analysis was performed using t-test with Bonferroni correction to identify significant differences. A level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Schematic Illustration of the Experimental System

To study the migratory properties of TGF-β1/EGF-activated TECs, we developed a novel two-compartment Boyden chamber system that attempts to mimic the in vivo tubulointerstitial compartment in health (Figure 1A) ▶ and in disease (Figure 1C) ▶ . For the purpose of this study we only focused on five players in the tubulointerstitium: the TECs, TBM, growth factors, fibroblast-like cells, and interstitial collagen (Figure 1, B and D) ▶ . A diagram of our in vitro model used in the present experiments is shown in Figure 1, E and F ▶ . The current concept of EMT postulates a mechanism in which TECs become activated by exogenous stimuli, followed by a loss of contact with neighboring cells and basement membrane. 1,16,40,41 After initiation of EMT, activated cells move through their basement membrane into the interstitial matrix where they potentially become detectable as fibroblast/myofibroblast-like cells. 16,30,40 Thus, in this hypothetical model of EMT, acquisition of mesenchymal phenotype by epithelial cells is associated with TBM degradation. In kidney tissue of patients with ESRD (membranous nephropathy), TECs around areas with intact basement membrane did not stain with the mesenchymal cell marker α-smooth muscle actin (Figure 1G) ▶ , whereas disruption of TBM correlated with α-smooth muscle actin expression in the TECs (Figure 1H) ▶ did. This observation suggests that EMT may correlate with alterations in TBM that potentially allow transit of TECs through the basement membrane to invade the interstitial matrix, thus making TBM a key central player in the progression of chronic renal disease.

Migratory Behavior of TECs to Chemotactic Stimuli and Increased Motility

During renal fibrosis, TGF-β1 and EGF are up-regulated in the renal interstitium and in the tubular compartment. 42-44 To delineate different properties of TGF-β1 in facilitating migration of TECs, we tested the migratory behavior of cells after direct stimulation with TGF-β1 in the upper chamber (mimicking the tubular compartment direct stimulation) or in the lower chamber (mimicking the interstitial compartment chemotactic stimuli). TECs migrated into the lower chamber across a polycarbonate membrane when TGF-β1 and/or EGF were used as chemotactic stimuli or as direct stimuli (Figure 2, A and C) ▶ . Soluble TGF receptor inhibited migration that was induced by chemotactic as well as direct stimulation with TGF-β1. Interestingly, soluble type I collagen, the most abundant collagen in the interstitium, 22 was chemotactic for TGF-β1-pretreated TECs when added to the lower chamber, whereas it had no effect when added to the upper chamber (Figure 2C) ▶ .

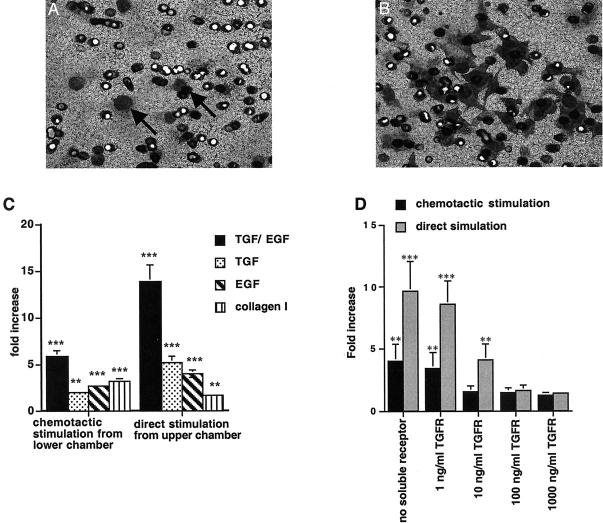

Figure 2.

Migration of TECs. A: TECs migrate into the lower chamber and are visible on the lower side of the polycarbonate membrane when TGF-β1 and EGF were used as chemotactic stimuli. B: Cells pretreated with TGF-β1/EGF displayed an increased migratory capacity and continued to be responsive to TGF-β1 and EGF. C, left: Stimulation of TECs with TGF-β1/EGF from the lower chamber led to a 5.8 ± 0.62-fold increase of migration compared to unstimulated control cells. Incubation with TGF-β1 led to a 2.0 ± 0.17-fold increase and incubation with EGF led to 3.66 ± 0.17-fold increase compared to nonstimulated control. C, right: Direct stimulation of MCT cells by TGF-β1 and EGF in the upper chamber led to a 13.8 ± 1.82-fold increase compared to the control. Direct stimulation with TGF-β1 led to a 5.2 ± 0.32-fold increase in migration compared to untreated control and direct stimulation with EGF led to a 3.96 ± 0.36-fold increase. The addition of type I collagen in the lower chamber induced migration of unstimulated TECs by 3.2 ± 0.31-fold, whereas the addition of type I collagen into the upper chamber had no significant effect. D: Addition of soluble TGF-β receptor to cells in the upper chamber inhibited TGF-β1-induced migration. D, gray columns: Migration that was induced by direct stimulation with TGF-β1 (9.6 ± 2.43-fold increase), was reduced to 8.6 ± 1.94-fold by the addition of 1 ng/ml of TGF-β receptor, to 4.1 ± 1.28-fold by the addition of 10 ng/ml of TGF-β receptor, to 1.6 ± 0.42-fold by the addition of 100 ng/ml of TGF-β receptor, and to 1.4 ± 0.12-fold by the addition of 1000 ng/ml of TGF-β receptor. D, black columns: Inhibition of migration induced by chemotactic stimulation with TGF-β1 (4.0 ± 1.34-fold increase) was reduced to 3.39 (±1.3)-fold increase by the addition of 1 ng/ml of TGF-β receptor, to 1.52 (±0.47)-fold at a concentration of 10 ng/ml, to 1.47 (±0,37)-fold at 100 ng/ml, and to 1.25 (±0.25)-fold at 1000 ng/ml). ***, P < 0.0001; **, P < 0.001; *, P < 0.05. Original magnification: ×200 (B).

Extracellular Matrix Regulates Migratory Response of Activated TECs

We next designed experiments that test the hypothesis that extracellular matrix microenvironment is important for the migration of TECs. Coating the upper side of the membrane with type IV collagen, a major constituent of TBM, decreased the chemotactic migration of TECs (Figure 3) ▶ . Inhibition of chemotactic migration was dramatic when the membrane was coated with a crude renal basement membrane preparation from bovine kidneys (Figure 3) ▶ . Interestingly, type IV collagen by itself was not sufficient to significantly inhibit the migration of TECs that were directly stimulated with TGF-β1/EGF. Migration of TECs after direct stimulation was partially inhibited by coating with crude TBM. These experiments suggest that chemotactic migration of TECs and migration because of direct regulation, are distinct potentially because of the differential capacity of these cells in the invasion of our crude basement membrane preparations. Coating the bottom side of the membrane with type I collagen increased the migratory response of TECs (Figure 3) ▶ . These experiments suggest that collagen type I, which is present outside renal tubules (as mimicked here), may play an important role in inducing migration of TECs when the TBM integrity is compromised.

Figure 3.

Regulation of migration by matrix microenvironment. A, left columns: Compared to chemotactic migration of MCT cells across an uncoated polycarbonate membrane, migration was significantly inhibited by coating the upper side of the membrane with type IV collagen [reduction by 44.6 (±2.5)% when compared to uncoated control]. Coating with bovine TBM preparation almost completely prevented chemotactic migrations of TECs in this setting [reduction by 88 (± 6.25)%]. A, right columns: Similarly, chemotactic migration of TECs across a membrane that was coated on the bottom side with type I collagen, was significantly inhibited by coating the upper side of the membrane with type IV collagen [reduction by 47.1 (±2.5)% when compared to control]. Also, TBM significantly inhibited chemotactic migrations of TECs [reduction by 92.2 (±6.3)%]. B, left columns: Migration of TECs across an uncoated membrane that was induced by direct stimulation with TGF-β1/EGF, was neither significantly inhibited by coating with type IV collagen, nor by coating with TBM. B, right columns: Migration of directly stimulated TECs across a membrane that was coated on the bottom side with type I collagen, was not significantly decreased by type IV collagen. Coating with bovine TBM preparation resulted in a decrease of migration in this setting, but was still permissive for migration of activated TECs [reduction by 49.3 (±1.3)% compared to uncoated control].

Regulation of Migratory Response of Activated TECs by Matrix-Degrading Proteases

To further delineate chemotactic migration from migration induced by direct stimulation of TECs across type IV collagen and crude TBM, we performed experiments to determine the expression of MMPs by TECs stimulated with TGF-β1/EGF. Activation of TECs by TGF-β1/EGF resulted in an increase of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in the culture supernatant. MMP-2 and MMP-9 have the potential to degrade basement membranes and generate degradation products as shown in several previous studies. 45-48 Active MMP-2 and MMP-9 can degrade bovine TBM and generate NC1 domain-containing fragments, as shown in Figure 4A ▶ . Additionally, incubation of bovine TBM with TEC culture supernatant treated with TGF-β1/EGF, which contains increased levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 (Figure 4, B to D) ▶ , specifically generates type IV collagen degradation products (Figure 4A) ▶ .

Figure 4.

Activation of TECs with TGF-β1 and EGF leads to increased degradation of TBM via up-regulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9. A: Incubation of bovine TBM with active MMP-9 and MMP-2 generates NC1 domains and other type IV collagen degradation products (26 kd and 48 kd) as observed by Western blot. Incubation of TBM with supernatant derived from TGF-β1/EGF-treated TECs led to the generation of type IV collagen degradation products containing NC1 domains, whereas supernatant from untreated control TECs did not significantly degrade TBM. B: Supernatant from MCT cells treated with TGF-β1/EGF exhibited a significant up-regulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 as observed by zymography assay using tissue culture supernatants. C and D summarize densitometric quantification of four independent experiments. *, P < 0.05.

To directly implicate the role of MMPs in the migration of activated TECs, COL-3, an inhibitor of MMP-2 and MMP-9, was used to inhibit TGF-β1/EGF-induced MMPs. 49,50 When TECs were directly stimulated with TGF-β1/ EGF, the addition of COL-3 significantly inhibited migration of these TECs through the bovine TBM preparation, demonstrating that MMPs are important in this setting. (Figure 5A) ▶ . The addition of COL-3 into the upper chamber had no significant effect on TEC migration when TGF-β1 and EGF were used as chemotactic stimuli in the lower chamber, demonstrating that this aspect of TEC migration is MMP-independent (Figure 5B) ▶ .

Figure 5.

Regulation of TEC migration. A: Inhibition of basement membrane-degrading MMP-2 and MMP-9 by COL-3, reduced migration that was induced by direct stimulation with TGF-β1/EGF across a polycarbonate membrane coated with bovine TBM preparation on the upper side and with type I collagen on the lower side in a dose-dependent manner [control 10.4 (±2.61)-fold stimulation, 8.91 (±1.98)-fold at 0.1 ng/ml, 4.57 (±1.48)-fold at 1 ng/ml, and 2.01 (±1.07)-fold at 10 ng/ml]. B: Migration induced by chemotactic stimulation with TGF-β1/EGF from the lower chamber, was not significantly inhibited by COL-3. ***, P < 0.0001; **, P < 0.001; *, P < 0.05.

Discussion

TBMs provide a tightly regulated microenvironment for normal function of TECs. 7 TBM facilitates numerous cell-matrix interactions that are pivotal for the maintenance of the epithelial phenotype. 13 Migration of TECs from the tubular compartment through TBM into the interstitium is considered to be a mechanism contributing to tubular atrophy and hence to the progression of renal fibrosis. 1,15,28,30

In the present study, we established a two-chamber system that partially mimics the tubular compartment, TBM, and the interstitial compartment. We show that direct stimulation of TECs by TGF-β1 and/or EGF results in an increased migratory response. TECs also respond to chemotactic stimulation by TGF-β1 and/or EGF and type I collagen in the lower chamber (interstitial compartment). These results suggest that autocrine release of TGF-β1 and EGF in the tubular compartment is one mechanism of TEC migration. Additionally the release of TGF-β1/EGF, potentially by inflammatory cells and fibroblasts in the interstitium, can induce migration of TECs when TBM integrity is compromised.

The present study provides valuable insights into the role of TBM in regulation of TEC behavior. TGF-β1 and EGF are important activators of TECs. 35,51 Factors and/or events that contribute to TGF-β1/EGF up-regulation in TECs is still an open question and the present study does not address this issue. However, this present study demonstrates that even on 6 hours of culture crude TBM constituents can anchor TECs in their compartment. The inhibitory effect of the TBM preparation was significantly stronger than that of type IV collagen protomers by themselves. We speculate that crude TBM may be more inhibitory because it may represent a much more mechanical barrier with interactions associated with type IV collagen, laminin, nidogen, and so forth. Although TGF-β1 does exhibit chemotactic properties for TECs, such effects are not realized if crude TBM is present. Also, migratory capacity through type IV collagen or TBM in this chamber system is associated with an increase in MMP-2 and MMP-9 levels. In this regard, COL-3 (an MMP-inhibitor) inhibits migration induced by direct stimulation with TGF-β1, whereas it has no effect on migration induced by chemotactic stimulation with TGF-β1.

These findings suggest two distinct MMP-dependent and MMP-independent mechanisms of migration for activated TECs. We hypothesize that the initial influences for migration of activated TECs must include degradation or manipulation of TBM architecture. This could be achieved by up-regulation of MMPs as shown in the present study. Once this process is in operation, type I collagen and the potentially higher concentrations of TGF-β1/EGF present outside in the interstitium, can further influence the migration of TECs by chemotactic mechanisms depending ideally on favorable concentration gradients established by type I collagen and TGF-β1. Therefore, protection of TBM integrity may play a pivotal role in inhibiting the TEC’s contribution to interstitial fibrosis. Intact TBM may play an important role in attenuating interstitial influences on TECs during renal fibrosis suggesting a crucial role for MMPs in the pathogenesis of chronic renal fibrosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Biogen, Inc., for their generous research gift of TGF-β soluble receptor, and Collagenex, Inc., for their gift of COL-3 inhibitor.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Raghu Kalluri, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Department of Medicine, RW 514, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, 330 Brookline Ave., Boston, MA 02215. E-mail: rkalluri@caregroup.harvard.edu.

Supported in part by grants DK51711 and DK55001 from the National Institutes of Health and research funds from the Program in Matrix Biology.

References

- 1.Stahl PJ, Felsen D: Transforming growth factor-beta, basement membrane, and epithelial-mesenchymal transdifferentiation: implications for fibrosis in kidney disease. Am J Pathol 2001, 159:1187-1192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muller GA, Zeisberg M, Strutz F: The importance of tubulointerstitial damage in progressive renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2000, 15:76-77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Remuzzi G, Bertani T: Pathophysiology of progressive nephropathies. N Engl J Med 1998, 339:1448-1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abrass CK, Berfield AK, Stehman-Breen C, Alpers CE, Davis CL: Unique changes in interstitial extracellular matrix composition are associated with rejection and cyclosporine toxicity in human renal allograft biopsies. Am J Kidney Dis 1999, 33:11-20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brito PL, Fioretto P, Drummond K, Kim Y, Steffes MW, Basgen JM, Sisson-Ross S, Mauer M: Proximal tubular basement membrane width in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Kidney Int 1998, 53:754-761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lohi J, Korhonen M, Leivo I, Kangas L, Tani T, Kalluri R, Miner JH, Lehto VP, Virtanen I: Expression of type IV collagen alpha1(IV)-alpha6(IV) polypeptides in normal and developing human kidney and in renal cell carcinomas and oncocytomas. Int J Cancer 1997, 72:43-49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miner JH: Renal basement membrane components. Kidney Int 1999, 56:2016-2024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mott JD, Khalifah RG, Nagase H, Shield CF, III, Hudson JK, Hudson BG: Nonenzymatic glycation of type IV collagen and matrix metalloproteinase susceptibility. Kidney Int 1997, 52:1302-1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sibalic V, Sun L, Sibalic A, Oertli B, Ritthaler T, Wuthrich RP: Characteristic matrix and tubular basement membrane abnormalities in the CBA/Ca-kdkd mouse model of hereditary tubulointerstitial disease. Nephron 1998, 80:305-313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreidberg JA, Symons JM: Integrins in kidney development, function, and disease. Am J Physiol 2000, 279:F233-F242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erickson AC, Couchman JR: Still more complexity in mammalian basement membranes. J Histochem Cytochem 2000, 48:1291-1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zuk A, Hay ED: Expression of beta 1 integrins changes during transformation of avian lens epithelium to mesenchyme in collagen gels. Dev Dyn 1994, 201:378-393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paulsson M: Basement membrane proteins: structure, assembly, and cellular interactions. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 1992, 27:93-127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frisch SM: Anoikis. Methods Enzymol 2000, 322:472-479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hay ED: An overview of epithelio-mesenchymal transformation. Acta Anat 1995, 154:8-20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeisberg M, Bonner G, Maeshima Y, Colorado P, Muller GA, Strutz F, Kalluri R: Renal fibrosis: collagen composition and assembly regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transdifferentiation. Am J Pathol 2001, 159:1313-1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Timpl R: Macromolecular organization of basement membranes. Curr Opin Cell Biol 1996, 8:618-624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yurchenco PD: Assembly of basement membranes. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1990, 580:195-213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Timpl R: Structure and biological activity of basement membrane proteins. Eur J Biochem 1989, 180:487-502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalluri R, Cosgrove D: Assembly of type IV collagen. Insights from alpha3(IV) collagen-deficient mice. J Biol Chem 2000, 275:12719-12724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aumailley M, Gayraud B: Structure and biological activity of the extracellular matrix. J Mol Med 1998, 76:253-265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eddy AA: Molecular insights into renal interstitial fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 1996, 7:2495-2508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bohle A, Christ H, Grund KE, Mackensen S: The role of the interstitium of the renal cortex in renal disease. Contrib Nephrol 1979, 16:109-114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strutz F, Muller GA: On the progression of chronic renal disease. Nephron 1995, 69:371-379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pozzi A, Wary KK, Giancotti FG, Gardner HA: Integrin alpha1beta1 mediates a unique collagen-dependent proliferation pathway in vivo. J Cell Biol 1998, 142:587-594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gardner H, Broberg A, Pozzi A, Laato M, Heino J: Absence of integrin alpha1beta1 in the mouse causes loss of feedback regulation of collagen synthesis in normal and wounded dermis. J Cell Sci 1999, 112:263-272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okada H, Inoue T, Suzuki H, Strutz F, Neilson EG: Epithelial-mesenchymal transformation of renal tubular epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2000, 15:44-46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strutz F, Muller GA: Transdifferentiation comes of age. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2000, 15:1729-1731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Birchmeier W, Birchmeier C: Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and tumor progression. EXS 1995, 74:1-15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hay ED, Zuk A: Transformations between epithelium and mesenchyme: normal, pathological, and experimentally induced. Am J Kidney Dis 1995, 26:678-690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fan JM, Ng YY, Hill PA, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Mu W, Atkins RC, Lan HY: Transforming growth factor-beta regulates tubular epithelial-myofibroblast transdifferentiation in vitro. Kidney Int 1999, 56:1455-1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strutz F, Muller GA, Neilson EG: Transdifferentiation: a new angle on renal fibrosis. Exp Nephrol 1996, 4:267-270 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuncio GS, Alvarez R, Li S, Killen PD, Neilson EG: Transforming growth factor-beta modulation of the alpha 1(IV) collagen gene in murine proximal tubular cells. Am J Physiol 1996, 271:F120-F125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strutz F, Okada H, Lo CW, Danoff T, Carone RL, Tomaszewski JE, Neilson EG: Identification and characterization of a fibroblast marker: FSP1. J Cell Biol 1995, 130:393-405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okada H, Danoff TM, Kalluri R, Neilson EG: Early role of Fsp1 in epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Am J Physiol 1997, 273:F563-F574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neilson EG, Jimenez SA, Phillips SM: Cell-mediated immunity in interstitial nephritis. III. T lymphocyte-mediated fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis: an immune mechanism for renal fibrogenesis. J Immunol 1980, 125:1708-1714 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zakheim B, McCafferty E, Phillips SM, Clayman M, Neilson EG: Murine interstitial nephritis. II. The adoptive transfer of disease with immune T lymphocytes produces a phenotypically complex interstitial lesion. J Immunol 1984, 133:234-239 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freytag JW, Ohno M, Hudson BG: Large scale preparation of bovine renal glomerular basement membrane in the presence of protease inhibitors. Prep Biochem 1978, 8:215-224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalluri R, Shield CF, Todd P, Hudson BG, Neilson EG: Isoform switching of type IV collagen is developmentally arrested in X-linked Alport syndrome leading to increased susceptibility of renal basement membranes to endoproteolysis. J Clin Invest 1997, 99:2470-2478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zeisberg M, Strutz F, Muller GA: Renal fibrosis: an update. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2001, 10:315-320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ng YY, Huang TP, Yang WC, Chen ZP, Yang AH, Mu W, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Atkins RC, Lan HY: Tubular epithelial-myofibroblast transdifferentiation in progressive tubulointerstitial fibrosis in 5/6 nephrectomized rats. Kidney Int 1998, 54:864-876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Border WA, Noble NA: Transforming growth factor beta in tissue fibrosis. N Engl J Med 1994, 331:1286-1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Border WA, Okuda S, Languino LR, Sporn MB, Ruoslahti E: Suppression of experimental glomerulonephritis by antiserum against transforming growth factor beta 1. Nature 1990, 346:371-374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Terzi F, Burtin M, Hekmati M, Federici P, Grimber G, Briand P, Friedlander G: Targeted expression of a dominant-negative EGF-R in the kidney reduces tubulo-interstitial lesions after renal injury. J Clin Invest 2000, 106:225-234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stetler-Stevenson WG, Aznavoorian S, Liotta LA: Tumor cell interactions with the extracellular matrix during invasion and metastasis. Annu Rev Cell Biol 1993, 9:541-573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vu TH, Werb Z: Matrix metalloproteinases: effectors of development and normal physiology. Genes Dev 2000, 14:2123-2133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kalluri R, Gunwar S, Reeders ST, Morrison KC, Mariyama M, Ebner KE, Noelken ME, Hudson BG: Goodpasture syndrome. Localization of the epitope for the autoantibodies to the carboxyl-terminal region of the alpha 3(IV) chain of basement membrane collagen. J Biol Chem 1991, 266:24018-24024 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gunwar S, Ballester F, Kalluri R, Timoneda J, Chonko AM, Edwards SJ, Noelken ME, Hudson BG: Glomerular basement membrane. Identification of dimeric subunits of the noncollagenous domain (hexamer) of collagen IV and the Goodpasture antigen. J Biol Chem 1991, 266:15318-15324 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Myers SA, Wolowacz RG: Tetracycline-based MMP inhibitors can prevent fibroblast-mediated collagen gel contraction in vitro. Adv Dent Res 1998, 12:86-93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seftor RE, Seftor EA, De Larco JE, Kleiner DE, Leferson J, Stetler-Stevenson WG, McNamara TF, Golub LM, Hendrix MJ: Chemically modified tetracyclines inhibit human melanoma cell invasion and metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis 1998, 16:217-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cosgrove D, Rodgers K, Meehan D, Miller C, Bovard K, Gilroy A, Gardner H, Kotelianski V, Gotwals P, Amatucci A, Kalluri R: Integrin alpha1beta1 and transforming growth factor-beta1 play distinct roles in Alport glomerular pathogenesis and serve as dual targets for metabolic therapy. Am J Pathol 2000, 157:1649-1659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]