Abstract

Cystinosis is a rare autosomal recessive metabolic disorder characterized by the intracellular accumulation of cystine, the disulfide of the amino acid cysteine, in many organs and tissues. Infantile nephropathic cystinosis is the most severe phenotype. Corneal crystal accumulation and pigmentary retinopathy were originally the most commonly described ophthalmic manifestations, but successful kidney transplantation significantly changed the natural history of the disease. As cystinosis patients now live longer, long-term complications in extrarenal tissues including the eye, have become apparent. A case of an adult patient with infantile nephropathic cystinosis is reported. He presented with many long-term ocular complications of cystinosis. After 4 years of follow-up, the patient died from sepsis. Pathology of the phthisical eyes demonstrated numerous electron transparent polygonal spaces, bounded by single membrane, in corneal cells, retinal pigment epithelial cells, and even choroidal endothelial cells. The ophthalmic manifestations and pathology of infantile nephropathic cystinosis are discussed and reviewed in light of the current report and other cases in the literature.

Keywords: cystine, cystinosis, eye, histopathology, infantile nephropathic cystinosis, lysosome

Introduction

Cystinosis was initially described by Aberhalden in 1903. 2 Cystinosis is a rare autosomal recessive metabolic disorder characterized by the intracellular accumulation of cystine, the disulfide of the amino acid cysteine.29, 43, 44 The responsible gene, CTNS, encodes cystinosin, a 367 amino acid integral membrane protein that transports cystine out of the lysosome.37, 61, 89 As a result of deficient or absent cystinosin, cystine accumulates within lysosomes and forms crystals in many tissues, including the kidneys, bone marrow, pancreas, muscle, brain and eye.

Based on age of onset and severity of symptoms, several cystinosis phenotypes have been described. 44 They are nephropathic and non-nephropathic. Nephropathic cystinosis further divides to infantile (classic) and intermediate (juvenile-onset or adolescent). Non-nephropathic cystinosis was formerly called benign or adult type cystinosis 19 but is now termed ocular cystinosis. Infantile nephropathic cystinosis, the most common and severe phenotype, presents with growth retardation and renal tubular Fanconi syndrome between 6 and 12 months of age and, if untreated, leads to renal failure by approximately 10 years of age.44, 83 Intermediate (late-onset nephropathic) cystinosis manifests the same symptoms but with a later age of onset.44, 47, 83 Ocular cystinosis presents only with corneal crystal deposition but no associated systemic manifestations.19, 44, 83 Different CTNS mutations produce the three different phenotypes, that vary based upon the amounts of residual cystinosin activity.5, 6 Here we report a clinicopathological case of infantile nephropathic cystinosis in an adult patient and review the literature regarding the disorder’s early ophthalmic manifestations and late-onset ocular complications.

Case Report

This infantile nephropathic cystinosis patient was initially seen at the National Eye Institute (NEI) at 31 years of age for initiation of topical cysteamine therapy. He was enrolled in a protocol approved by the NEI Institutional Review Board and gave written informed consent. He complained of longstanding photophobia and foreign body sensation in his corneas. Past ophthalmic history included a keratoplasty in his right eye and bilateral ischemic diabetic retinopathy. On ocular examination best corrected visual acuity was 20/400 in the right eye and 20/320 in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination revealed early band keratopathy in both eyes. Whereas the donor cornea in the right eye was crystal-free, the host corneal bed and the left cornea exhibited abundant corneal crystals. Both irides were thickened and packed with crystals and posterior synechiae could be visualized in the right eye. Funduscopic examination of the right eye revealed intraretinal crystals with macular and peripheral pigmentary changes (Fig. 1A). A limited view of the left fundus prevented clear delineation of macular changes in the left eye, but indocyanine green videoangiography revealed a submacular choroidal neovascular membrane with feeder vessel; intraretinal crystals were also detected, as we previously reported (Fig. 1B). 90 Humphrey visual fields and electroretinography confirmed the presence of retinopathy. The patient failed to comply with the hourly regimen of topical cysteamine treatment. His ophthalmic complications progressed and included recurrent, spontaneous hyphema and hemorrhages in the vitreous and retrobulbar space of the right eye secondary to anticoagulation therapy. When seen at the NIH Clinical Center in follow-up at the age of 33, the right eye had become phthisical. Both eyes had developed severe band keratopathy that prevented any further evaluation (Fig. 2).

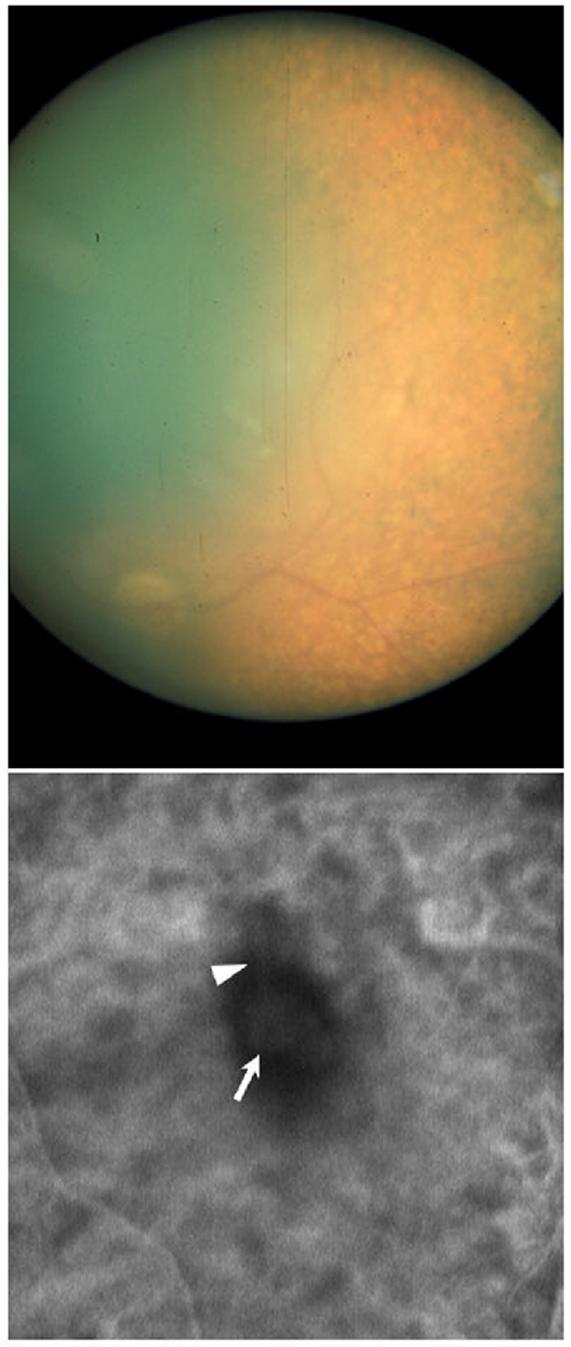

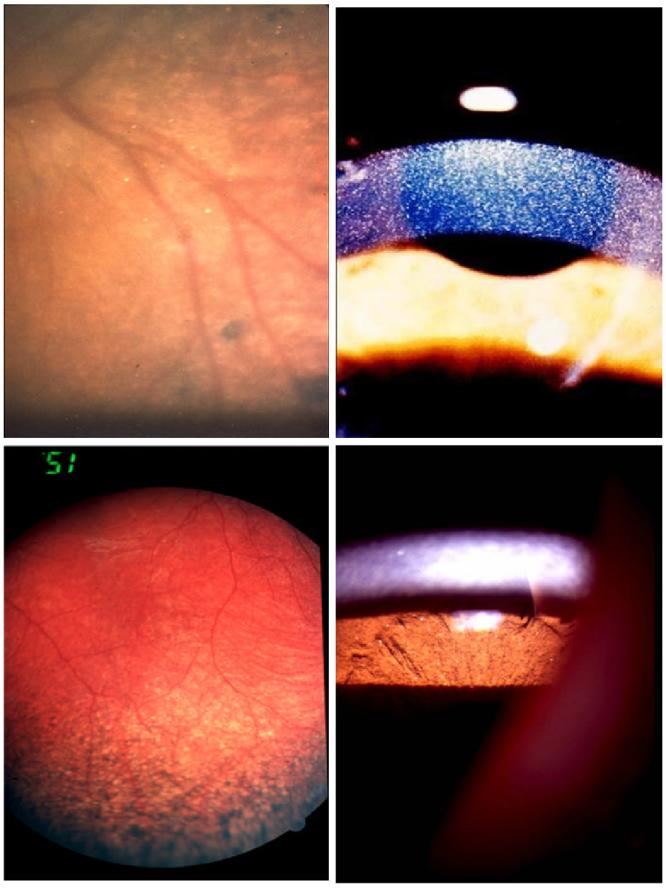

Figure 1.

Fundus photograph of the right eye (A) and ICG-V image of the left fundus (B). Typical retinal pigmentary changes are obvious in the retinal periphery of the right eye (A). A subfoveal choroidal neovascular membrane (arrow) with contiguous feeding vessel (arrowhead) are evident in the left eye (B). Please note the poor quality of the fundus photograph, due to the cornea opacification and the inadequate dilation achieved secondary to the posterior synechiae.

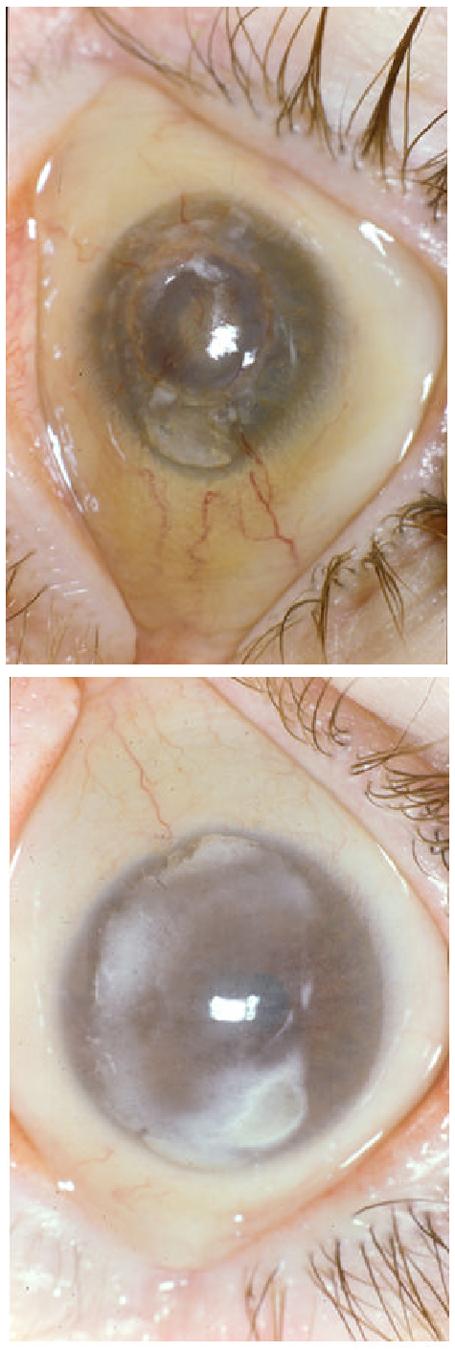

Figure 2.

Slit lamp photograph of right eye (A) and left eye (B). Calcification is present in both corneas. Severe cornea neovascularization is seen in the right cornea.

The patient died from sepsis at the age of 35. Autopsy findings included necrotizing peritonitis involving the small bowel and colon, fibrinous pericarditis and pleuritis, ascites, systemic and pulmonary edema, and hemorrhagic urocystitis. There were hepatic and splenic infarctions, cardiomegaly, and atherosclerosis, along with findings typical of cystinosis, such as short stature, retarded sexual development, atrophic kidneys, and a small thyroid gland. Particular attention was paid to the eyes that were donated for pathology.

Pathological Findings

ROUTINE HISTOLOGY

Macroscopic examination revealed a calcified and phthisical right eye (Fig. 3B), measuring 17 (AP) x 20 (H) x 17.5(V) mm, whereas the left eye measured 20 x 23 x 22.5 mm. A central ulceration surrounded by a small amount of hemorrhage was also noted in the right cornea (Fig. 3A). Both eyes were decalcified for processing.

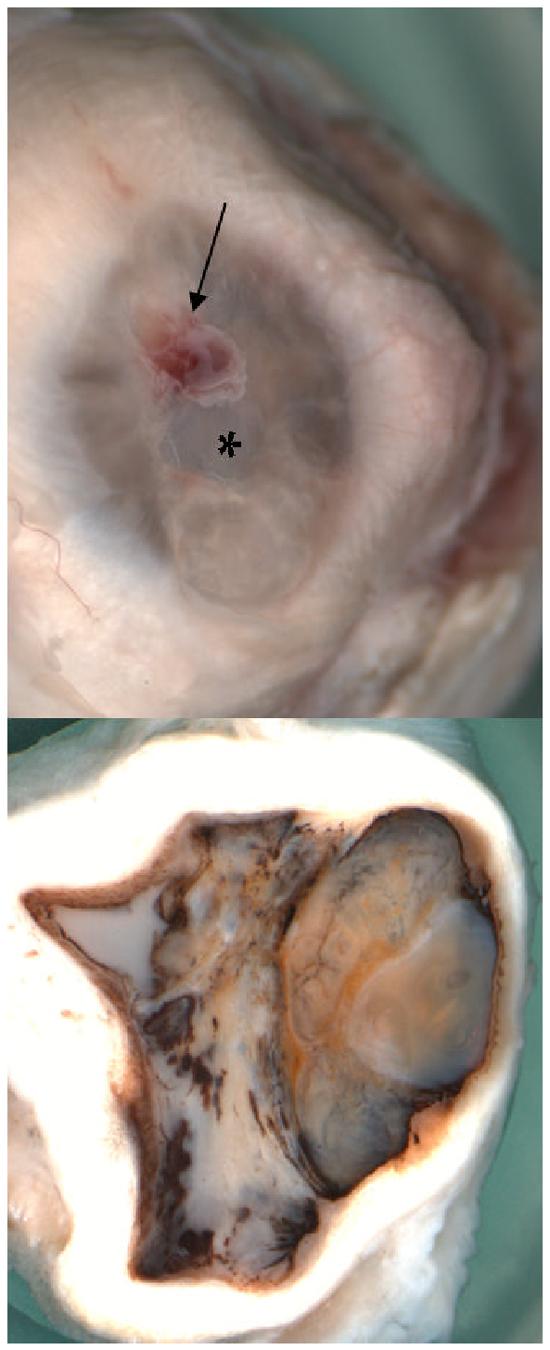

Figure 3.

Macroscopic photographs of the right eye showing (A) a central corneal ulceration (asterisk) surrounded by a patch of hemorrhage (arrow); (B) a total obliterated anterior chamber, compressed ciliary body, hypermature cataract lens (L), vitreous cavity filled with white necrotic material, partial choroidal detachment, and thickened sclera (S).

Microscopic examination disclosed corneal scars, neovascularization, and mild keratitis of the corneas; the right was more severe than the left eye (Fig. 4A and Fig. 5A). Both irides showed synechiae and atrophy. In addition, rubeosis and sclerotic iris, a cyclitic membrane in the right eye and a ciliary body hemorrhage in the left were observed. There were mature cataracts, retinal detachment and choroidal neovascularization in both eyes (Fig. 4B and Fig. 5B). In contrast, the right eye demonstrated massive subretinal fibrosis and focal retinal necrosis (secondary to sepsis) (Fig. 4B); the left eye showed a chorioretinal scar. The optic nerves showed atrophy and gliosis, the right eye was much worse than the left eye. Immunohistochemistry studies revealed the presence of scattered macrophages in the area of the choroidal neovascular membrane and retina (Fig. 6).

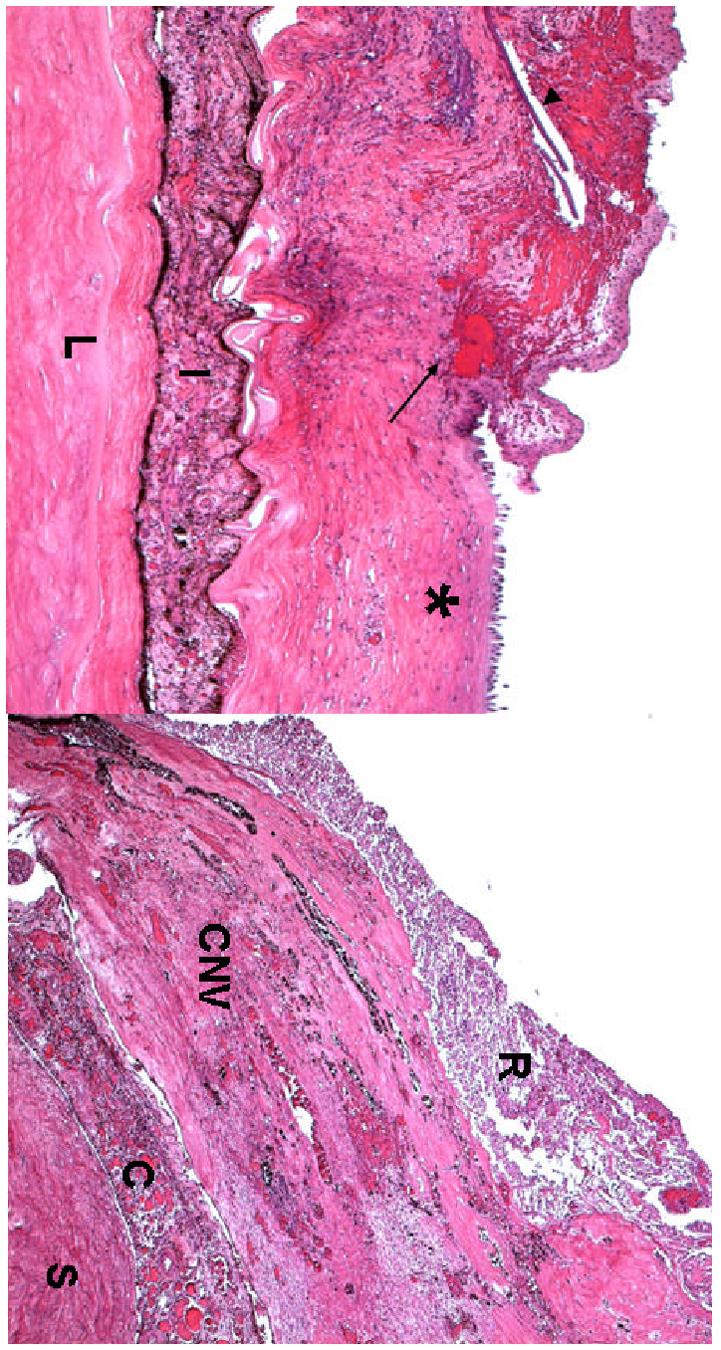

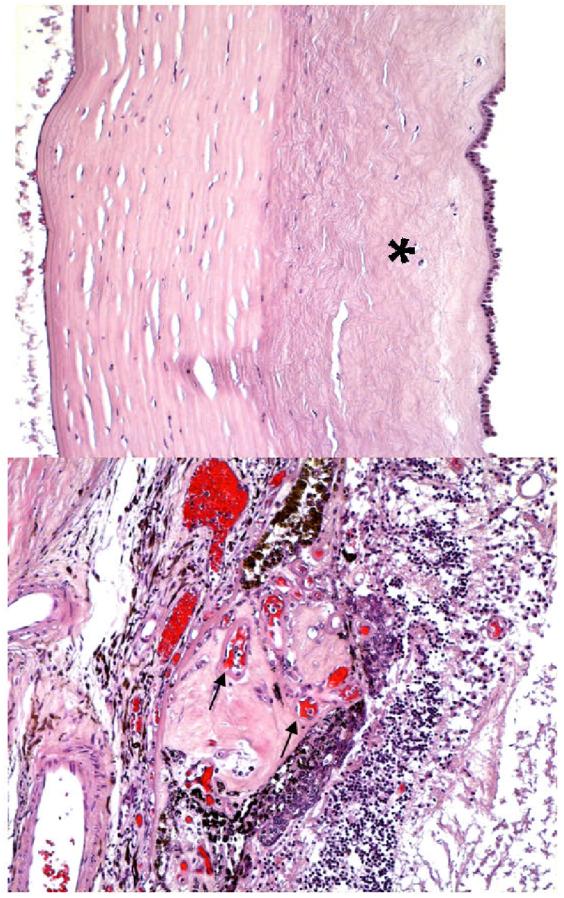

Figure 4.

Microphotographs of the right eye showing (A) the corneal ulcer (asterisk), surrounded by hemorrhages (arrow), neovascular fibrous tissue with linear calcified deposits (arrowhead), (I = iris, L= lens); (B) a thick layer of subretinal fibrosiscomposed of many small congested vessels (CNV) beneath the necrotic retina. (R = retina, CNV = choroidal neovascularization, C = choroid; S = sclera; hematoxylin-eosin, A x 50, B x 100)

Figure 5.

Microphotographs of the left eye showing (A) a thin, delicate collagen scars (asterisk) replaced Bowman’s membrane and the anterior half of the stroma; (B) a large choroidal nodule composed of multiple small congested vessels (arrows) beneath the disrupted RPE and disorganized neuro-retina. (hematoxylin-eosin, A x 100,B x 200)

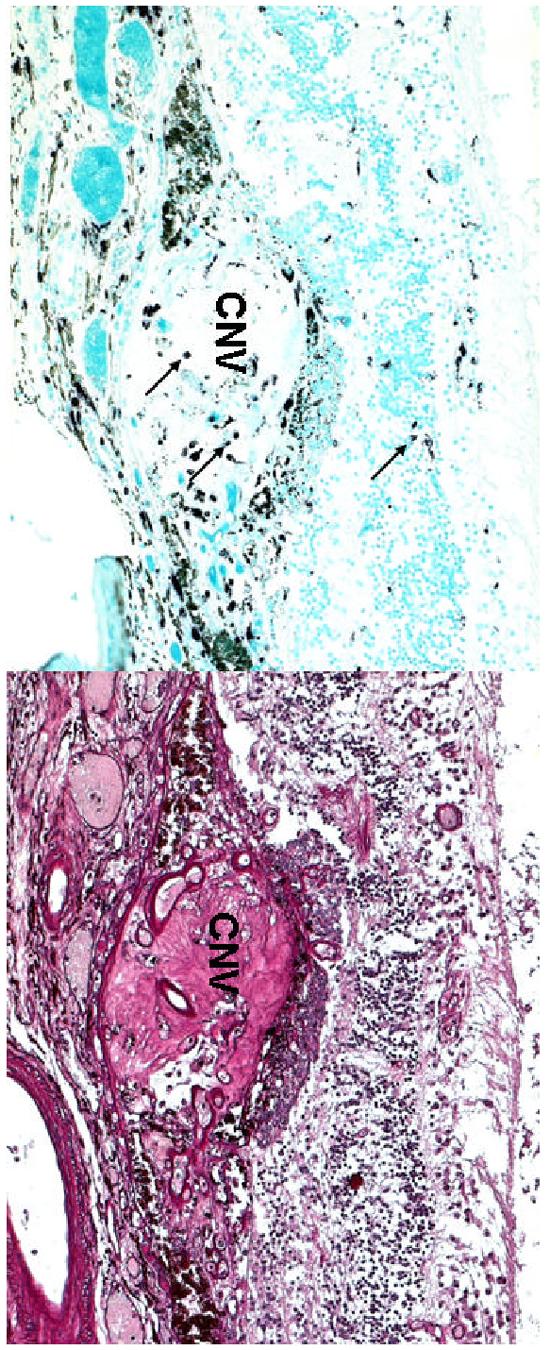

Figure 6.

Microphotographs of the left eye showing (A) scattered macrophages (arrows) located in the choroidal neovascular nodule (CNV) and retina. (B) multiple small vascular lumens in the CNV. (A, abc immunohistochemistry, x 100; B, Periodic Acid Schiff, x 100)

TRANSMISSION ELECTRON MICROSCOPY

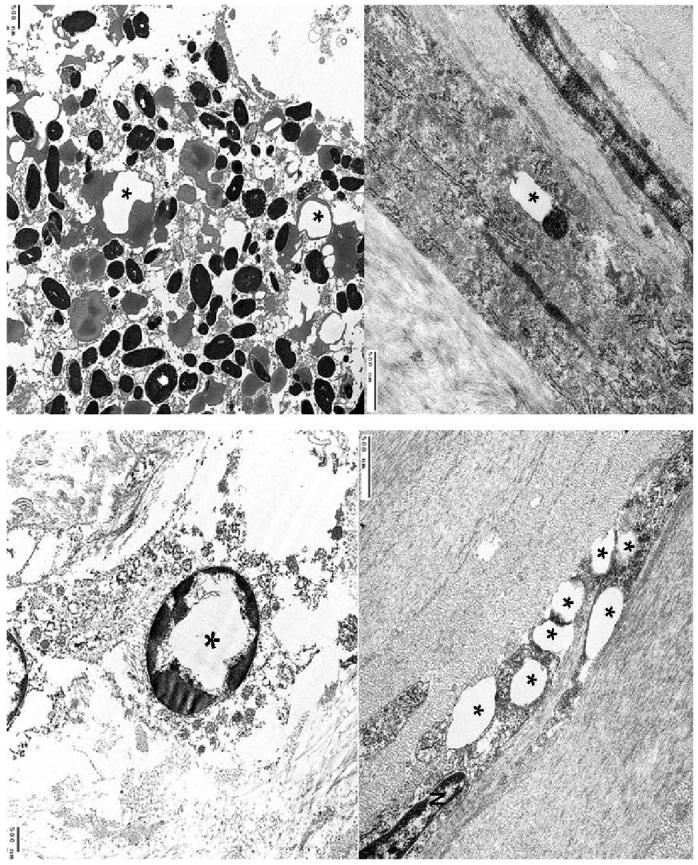

Ultrastructural examination was able to be performed on the less decalcified left eye. Numerous electron transparent polygonal spaces bounded by a single membrane were evident in or adjacent to the lysosomes of the corneal cells (Figs. 7A and 7B), retinal pigment epithelial cells (Fig. 7C), and some choroidal resident cells (Fig. 7D). In the corneal epithelial cell layer, multiple polygonal angular-shaped electron transparent areas of variable sizes were located in the perinuclear cytoplasm and cellular conjunction regions. In the corneal stroma these characteristic structures oriented parallel to the stroma lamellae were bounded by the same single membrane (Fig. 7A). In the cytoplasm of the RPE, there were prominent phagosomes containing polygonal electron transparent structures bounded by a single membrane (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

Transmission electron micrographs showing (A) a prominent, polygonal electron-transparent area (asterisk) and adjacent lysosome bounded by the same single membrane in the cytoplasm of a keratocyte. (B) multiple polygonal electron-transparent structures (asterisks) in the cytoplasm of another keratocyte (N, nucleus). (C) prominent phagosomes containing polygonal electron-transparent structures (asterisks) bounded by a single membrane in the cytoplasm of a RPE cell; (D) intracytoplasmic electron-transparent area bounded by a single membrane (asterisk) in a choroidal fibroblast .

The pathological findings confirmed bilateral end stage cystinosis.

Discussion

Intralysosomal cystine crystal accumulation is considered the primary cause of the specific tissue and organ involvement in cystinosis. The pathological findings in the eyes of our patient highlight this key feature of cystinosis. Here we review and compare the ocular findings of the present case with those of other infantile nephropathic cystinosis cases reported in the literature.

OPHTHALMIC MANIFESTATIONS

Crystal accumulation in the conjunctiva and cornea is the pathognomonic ophthalmic manifestation of cystinosis. This was initially described by Bürki in 1941,16 and has been observed in all subsequently reported cases.

Corneal crystals present as myriad needle-shaped, highly reflectile opacities easily seen by slit-lamp examination.9, 16, 18, 23, 32, 85, 95 They appear to be present in the corneal epithelium, stroma and endothelium.4, 50, 77 Due to their characteristic appearance and distribution they are easily, with few exceptions,34, 71 differentiated from other crystalline keratopathies.11, 52 Accumulation of crystals in the cornea starts in infancy and is definitely evident by 16 months of age. 40 Deposition begins in the anterior periphery and proceeds posteriorly and centripetally. By approximately 7 years of age, the entire peripheral stroma and endothelium accumulates crystals. By approximately 20 years of age, crystals can be seen in the entire corneal stroma. Crystal deposition advances more rapidly in the periphery. 75 Increased density of cystine crystals results in a hazy cornea that is easily recognizable with the naked eye in older, untreated cystinosis patients.

Corneal crystals are initially asymptomatic, but photophobia can develop within the first few years of life. 82 The severity of photophobia varies in ambient light but nearly all patients have some degree of discomfort with bright illumination after the first decade of life. Many patients require dark glasses in bright illumination and some have significant blepharospasm. Superficial punctate keratopathy with associated foreign body sensation and pain is occasionally seen, mostly in patients older than 10 years of age.28, 55 64 Katz et al documented loss of contrast sensitivity, increased glare disability, decreased corneal sensitivity and increased corneal thickness in patients with nephropathic cystinosis; he speculated that these changes are the result of cornea crystal deposition.62 65, 66, 67 Corneal crystals do not affect the visual acuity, so decreased visual acuity should prompt an investigation of other causes. 45

Conjunctival crystals are also seen by slit lamp biomicroscopy and give the conjunctiva a ground glass appearance.9, 16, 20, 95 They are whiter and not as highly reflectile as corneal crystals and therefore less photogenic.

Crystals have also been reported in the anterior chamber, iris and ciliary body, choroid, fundus and optic nerve.1, 7, 16, 44, 55, 78

A pigmentary retinopathy has also been seen in cystinosis patients.30, 31, 97 This finding precedes the appearance of the cornea crystals and has been seen as early as 5 weeks of age 97; the changes may be present as early as fetal life. 84 Pigmentary retinopathy, though, does not appear to be a constant finding. 12 The most commonly described ophthalmoscopic abnormality consists of patches of depigmentation with pigmentary mottling.79, 95, 97 The pigmentary abnormality is confined to the periphery in the early stages; changes are more marked in the temporal than the nasal segments and appear bilateral and symmetric.32, 97 As the child grows older, changes progress posteriorly; macular abnormalities have been described as early as 6 years of age. 81 Fluorescein angiography reveals window defects corresponding to the patches of depigmentation. 95 With the exception of a 5-year-old girl, 78 no abnormality in visual function was initially believed to accompany this early finding because end-stage renal failure and death supervened before 10 years of age.32, 95, 97 Fig. 8 features several classical ophthalmic manifestations of cystinosis from our collections.

Figure 8.

Ophthalmic manifestations of infantile nephropathic cystinosis: corneal crystals (A), iris crystals (B), retinal crystals (C), peripheral retinal pigmentary changes (D).

Since the initiation of successful renal transplantation and cystine depleting therapy, however, cystinosis patients are living longer 44 and manifesting the long-term complications of the disease in multiple organ systems. The initial experience with post-transplant patients revealed no significant ocular problems. 98 With longer follow-up, though, several ophthalmic complications came to light.12, 13, 25, 27, 36, 42, 46, 55, 87, 92, 94 We have reported anterior segment complications in older nephropathic cystinosis patients. 92 Superficial punctate keratopathy and filamentary keratopathy, although occasionally seen in the younger patients, are much more frequent in the older patients. Band keratopathy and peripheral corneal neovascularization are most commonly reported in post-transplant patients. Posterior synechiae associated with iris thickening or transillumination as well as angle abnormalities can occasionally lead to pupillary-block glaucoma and phthisis.55 76, 94 Crystals on the surface of the anterior capsule of the lens as well as a vascular membrane in the pupillary space have been reported. 55 A similar membrane was also present in the right eye of our present patient.

In addition to the anterior segment complications, retinal degeneration occurs, accompanied by variable degree of abnormality in psychophysical and electrodiagnostic testing.12, 13, 25, 27, 36, 39, 42, 55, 72 The only series described with no significant ocular complications in older patients comes from a French Canadian population, possibly because of particular mutations in this genetically homogeneous population. 80 Optic nerve disc elevation has recently been observed in several of our cystinosis patients and in several of them, further testing confirmed the presence of pseudotumor cerebri. 22 The etiology of this finding remains unelucidated, although corticosteroid intake and chronic renal failure may play a role.

Photophobia often progresses in older patients and can lead to severe blepharospasm, which alters quality of life.3, 27, 36, 39, 42 Decreased visual acuity can result from both anterior and posterior segment complications. Decreased color, peripheral and night vision are often encountered by older cystinosis patients.

OCULAR HISTOPATHOLOGY

Histopathology of the eye in nephropathic cystinosis was first reported by Bürki in 1941 and later documented by many other authors.9, 14, 15, 16, 18, 20, 21, 24, 25, 26, 32, 33, 56, 69, 75, 81, 86, 94, 95, 96, 97 The histopathologic findings supported clinical descriptions of cystinotic eyes. Due to their water-solubility, most cystine crystals are lost in aqueous fixatives. When processed in absolute alcohol, however, the crystals are identified within intracellular, single membrane-bound lysosomes.21, 68, 69, 96 X-ray diffraction studies have shown the crystals to be L-cystine.7, 33 In the conjunctiva hexagonal or rectangular, intracellular or extracellular crystals are scattered abundantly throughout the whole stroma, with some predilection for the subepithelial region and the walls of blood vessels.20, 85 In the cornea, the crystals are needle shaped and oriented parallel to the corneal stromal lamellae. They are less birefringent than the conjunctival crystals and are very difficult to identify. The crystals are best seen in thick or flat sections of the cornea and visualized by dark field illumination or between crossed polaroids.18, 32, 56, 81 Abundant crystals have also been reported in the sclera, rectangular in the outer layers and needle shape in the inner. 97 Crystals are also found in the iris, ciliary body, and choroid and retinal pigment epithelium.25, 33, 81, 94 In some studies, crystals were absent from the retina, vitreous, lens and optic nerve.18, 97 However, rare crystals have been reported in the retina and optic nerve. 44

In addition to the deposition of cystine crystals, Kaiser-Kupfer et al reported breaks in the Bowman’s membrane and mild focal inflammation in the conjunctiva. 56 Large perinuclear vacuoles containing a granular material were illustrated ultrastructurally, possibly representing amorphous non-crystalline cystine. 69 Focal degeneration has been frequently noted in the retinal pigment epithelium and pigment migration into the inner retina has been seen on occasion.25, 26, 32, 95, 97 Focal destruction of the outer segments of the photoreceptors has also been reported.26

UNIQUE FINDINGS OF THIS CASE

Our patient presents several new and distinctive pathologic findings that have not been documented in the literature. The large polygonal angular-shaped electron transparent areas most likely reflect cystine accumulation. They are different from the previously well-documented needle shaped crystals reported in the cornea of mostly younger cystinosis patients.18, 33, 56, 68, 69 Melles et al did describe the presence of rectangular intracytoplasmic crystalline inclusions within stromal keratocytes in a corneal button obtained from a 20-year-old patient but did not further discuss this finding. 75 Corneal crystals are thought to acquire their needle shape as they are forced from the tightly packed corneal stromal lamellae. The reason for the unusual shape of the cornea crystals in our patient may be that increased accumulation of cystine over the years disrupted the normal corneal stromal architecture, allowing the cystine to assume this shape. In addition, electron-lucent or transparent lysosomes or large crystal-like deposits are demonstrated in the RPE and choroidal cells. Third, the submacular choroidal neovascularization represents a new finding in cystinosis; its etiology is unknown. Immunohistochemical studies in our patient revealed moderate accumulation of macrophages in this area. We speculate that chronic heavy accumulation of cystine crystals leads to inflammation that triggers release of neovascular or ischemic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) leading to neovascularization.

TREATMENT

Treatment for infantile nephropathic cystinosis was initially symptomatic, primarily consisting of electrolyte replacement therapy. For the ophthalmic complications few corneal transplants were performed but there was a suggestion of recurrence of crystals in the transplanted cornea.57, 58, 63, 64 If so, the crystals had to be due to the invasion of host cells containing cystine-storing lysosomes.

The introduction of therapy with cysteamine, a cystine-depleting agent, in the 1970s has revolutionized the treatment and prognosis of cystinosis.38, 41 Cysteamine (β-mercaptoethylamine) is a simple aminothiol that depletes cystinotic cells of cystine.38, 88 After traversing the plasma and lysosomal membranes, cysteamine reacts with cystine to produce cysteine and the mixed disulfide cysteine-cysteamine, both of which freely exit the lysosome; the mixed disulfide utilizes a functional lysine transport system. Cysteamine treatment, if started early and taken diligently, can stabilize glomerular function, improve growth velocity, and obviate the requirement for thyroid hormone replacement.35, 41, 70, 74 We have recently documented a direct correlation between years off cysteamine treatment and the frequency of cystinotic retinopathy. 91 Although oral cysteamine alleviates most of the symptoms associated with cystinosis, it has no effect on the corneal crystal accumulation, most likely due to inadequate local cysteamine concentrations. 17 In several single-center and one multicenter trial, topical cysteamine treatment has proven safe and efficient in dissolving corneal crystals in both young and old cystinosis patients; it also significantly alleviates the symptoms of photophobia, blepharospasm and eye pain.8, 10, 48, 49, 51, 53, 54, 59, 60, 73, 93 The recommended regimen is a 0.55% (50 mM) cysteamine hydrochloride solution with benzalkonium chloride 0.01% as a preservative, used 10-12 times per day. 60 It is important to note that, at room temperature, the active free thiol, cysteamine, oxidizes to the disulfide form, cystamine, requiring shipping and storage of the topical solution in the frozen state. The formulation may be used at room temperature for up to 1 week. The special shipping and storage requirements have been a contributing factor in the delay of submission of a New Drug Application (NDA) to the FDA for the standard formulation. Attempts to create a new cysteamine formulation that remains stable at room temperature have been unsuccessful53, 93 and submission of an NDA for the standard formulation is expected within the near future.

Method of Literature Search

We consulted chapters on cystinosis in volumes 3, 7, 8, 9,10 and 15 of Sir Stewart Duke-Elder’s System of Ophthalmology to review the history of this disease and ascertain early references. The early papers by Abderhalden, Bűrki and Erlenmeyer describing the disease were used as the basis for a cited-reference search in Science Citation Index (1955-February 10, 2006) via Web of Science. We also conducted a Medline search using the PubMed interface including Old Medline records from 1950-February 10, 2006. Eye-related terms (EYE or EYE DISEASES as MeSH headings, or text words cornea* OR retina* OR retini* OR kerato* OR kerati* OR conjunctiv* OR retinopath* OR ocular OR synechi* OR choroid* OR iris OR irises OR irides OR ophthalm* OR vitreous OR vitreal OR intravitreal OR phthisis OR macula OR macular OR submacular OR maculop* OR sclera OR scleral OR uvea* OR episcler* OR subconjunctiva* OR eye OR eyes) were combined with cystinosis-related terms (CYSTINOSIS or CTNS PROTEIN, HUMAN or CYSTEAMINE as MeSH headings, or text words cystin* OR cysteamine OR mercaptoethylamine OR ctns). In addition, Embase.com (1974-February 10, 2006) was searched using a similar strategy. Scopus (1966-February 10, 2006) and Web of Science (1955-February 10, 2006) were searched using only the keyword list developed for the Medline search, since neither of those databases includes subject indexing. Citations identified by the Web of Science search were also used to check cited and citing records. Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature was searched using the OVID interface, using EYE or EYE DISEASES as indexing terms, or the Medline-developed list of natural language terms, and CYSTINOSIS as an indexing term or keywords cystine OR cystinic OR ctns OR cysteamine OR mercaptoethylamine.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NEI. The authors reported no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

Reprint address: Ekaterini Tsilou, MD, Ophthalmic Genetics and Visual Function Branch, National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, 10 Center Drive, MSC-1860, Building 10, Room 10N226, Bethesda, MD 20892. E-mail: tsiloue@nei.nih.gov

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.___ Feature photo. Cystinosis with extensive choroidal involvement. Arch Ophthalmol. 1965;74:868–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1965.00970040870025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aberhalden E. Familiare cystidiathesis. ZtschrPhysiol Chem. 1903;38:557. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almond PS, Matas AJ, Nakhleh RE, et al. Renal transplantation for infantile cystinosis: long-term follow-up. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:232–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(05)80282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alsuhaibani AH, Khan AO, Wagoner MD. Confocal microscopy of the cornea in nephropathic cystinosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:1530–1. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.074468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anikster Y, Lucero C, Guo J, et al. Ocular nonnephropathic cystinosis: clinical, biochemical, and molecular correlations. Pediatr Res. 2000;47:17–23. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200001000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Attard M, Jean G, Forestier L, et al. Severity of phenotype in cystinosis varies with mutations in the CTNS gene: predicted effect on the model of cystinosin. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2507–14. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.13.2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bickel H, Smellie JM. Cystine storage disease with amino-aciduria. Lancet. 1952;1:1093–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(52)90750-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blanksma LJ, Jansonius NM, Reitsma-Bierens WC. Cysteamin eyedrops in three patients with nephropathic cystinosis. Doc Ophthalmol. 19961997;92:51–3. doi: 10.1007/BF02583276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boniuk M, Hill LL. Ocular manifestations of de Tonifanconi syndrome with cystine storage disease. South Med J. 1966;59:33–40. doi: 10.1097/00007611-196601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradbury JA, Danjoux JP, Voller J, et al. A randomised placebo-controlled trial of topical cysteamine therapy in patients with nephropathic cystinosis. Eye. 1991;5(Pt 6):755–60. doi: 10.1038/eye.1991.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brooks AM. Corneal crystals. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1990;18:121–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1990.tb00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broyer M, Guillot M, Gubler MC, et al. Infantile cystinosis: a reappraisal of early and late symptoms. Adv Nephrol Necker Hosp. 1981;10:137–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broyer M, Tete MJ, Gubler MC. Late symptoms in infantile cystinosis. Pediatr Nephrol. 1987;1:519–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00849263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burki E. [On cystinosis of the eyes.] Bull Schweiz Akad Med Wiss. 1962;17:411–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burki E. [Another case of cystinosis with corneal changes.] Ophthalmologica. 1954;127:309–14. doi: 10.1159/000301972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burki E. Über die Cystinkrankheit im Kleinkindesalter unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Augenbefundes. Ophthalmologica. 1941;101:257–72. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cantani A, Giardini O, Ciarnella Cantani A. Nephropathic cystinosis: ineffectiveness of cysteamine therapy for ocular changes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;95:713–4. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(83)90401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cogan DG, Kuwabara T. Ocular pathology of cystinosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1960;63:51–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1960.00950020053008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cogan DG, Kuwabara T, Kinoshita J, et al. Cystinosis in an adult. JAMA. 1957;164:394–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.1957.02980040034009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cogan DG, Kuwabara T, Kinoshita J, et al. Ocular manifestations of systemic cystinosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1956;55:36–41. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1956.00930030038008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cruz-Sánchez FF, Cervós-Navarro J, Rodríguez-Prados S, et al. The value of conjunctival biopsy in childhood cystinosis. Histol Histopathol. 1989;4:305–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dogulu CF, Tsilou E, Rubin B, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension in cystinosis. J Pediatr. 2004;145:673–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.06.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Douglas A. Four Cases of Nuclear Agenesis. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1950;70:98–100. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dufier JL. Ophthalmologic involvement in inherited renal disease. Adv Nephrol Necker Hosp. 1992;21:143–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dufier JL, Dhermy P, Gubler MC, et al. Ocular changes in long-term evolution of infantile cystinosis. Ophthalmic Paediatr Genet. 1987;8:131–7. doi: 10.3109/13816818709028529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dufier JL, Orssaud D, Dhermy P, et al. Ocular changes in some progressive hereditary nephropathies. Pediatr Nephrol. 1987;1:525–30. doi: 10.1007/BF00849264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dureau P, Broyer M, Dufier JL. Evolution of ocular manifestations in nephropathic cystinosis: a long-term study of a population treated with cysteamine. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2003;40:142–6. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-20030501-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elder MJ, Astin CL. Recurrent corneal erosion in cystinosis. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1994;31:270–1. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19940701-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erlenmeyer E. Synthese des Cystins. 1903. pp. 2720–2. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Francois J. Hereditary Chorio-Retinal Degenerations And Metabolic Disturbances. Exp Eye Res. 1964;15:405–11. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(64)80052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.François J. Metabolic tapetoretinal degenerations. Surv Ophthalmol. 1982;26:293–333. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(82)90124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.François J, Hanssens M, Coppieters R, et al. Cystinosis. A clinical and histopathologic study. Am J Ophthalmol. 1972;73:643–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frazier PD, Wong VG. Cystinosis. Histologic and crystallographic examination of crystals in eye tissues. Arch Ophthalmol. 1968;80:87–91. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1968.00980050089014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gabel J, Seitz B, Hantsch A, et al. [Crystalline keratopathy as a presenting sign of multiple myeloma] Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1999;214:412–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1034822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gahl WA. Early oral cysteamine therapy for nephropathic cystinosis. Eur J Pediatr. 2003;162(Suppl 1):S38–41. doi: 10.1007/s00431-003-1349-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gahl WA. Cystinosis coming of age. Adv Pediatr. 1986;33:95–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gahl WA, Bashan N, Tietze F, et al. Cystine transport is defective in isolated leukocyte lysosomes from patients with cystinosis. Science. 1982;217:1263–5. doi: 10.1126/science.7112129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gahl WA, Charnas L, Markello TC, et al. Parenchymal organ cystine depletion with long-term cysteamine therapy. Biochem Med Metab Biol. 1992;48:275–85. doi: 10.1016/0885-4505(92)90074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gahl WA, Kaiser-Kupfer MI. Complications of nephropathic cystinosis after renal failure. Pediatr Nephrol. 1987;1:260–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00849221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gahl WA, Kuehl EM, Iwata F, et al. Corneal crystals in nephropathic cystinosis: natural history and treatment with cysteamine eyedrops. Mol Genet Metab. 2000;71:100–20. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2000.3062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gahl WA, Reed GF, Thoene JG, et al. Cysteamine therapy for children with nephropathic cystinosis. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:971–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704163161602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gahl WA, Schneider JA, Thoene JG, et al. Course of nephropathic cystinosis after age 10 years. J Pediatr. 1986;109:605–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gahl WA, Thoene J, Schneider J. Cystinosis. In: Scriver CR, Beaudetal, Sly WS, et al., editors. A disorder of lysosomal membrane transport. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease New-York; McGraw-Hill: 2000. pp. 5085–108. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gahl WA, Thoene JG, Schneider JA. Cystinosis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:111–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gahl WA, Thoene JG, Schneider JA, et al. NIH conference. Cystinosis: progress in a prototypic disease. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:557–69. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-7-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Geelen JM, Monnens LA, Levtchenko EN. Follow-up and treatment of adults with cystinosis in the Netherlands. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:1766–70. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.10.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldman H, Scriver CR, Aaron K, et al. Adolescent cystinosis: comparisons with infantile and adult forms. Pediatrics. 1971;47:979–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gräf M, Grote A, Wagner F: [Cysteamine eyedrops for treatment of corneal cysteine deposits in infantile cystinosis] Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1992;201:48–50. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1045868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gräf M, Kalinowski HO. [1H-NMR spectroscopic study of cysteamine eyedrops] Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1995;206:262–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1035436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grupcheva CN, Ormonde SE, McGhee C. In vivo confocal microscopy of the cornea in nephropathic cystinosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1742–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hsuan JD, Harding JJ, Bron AJ. The penetration of topical cysteamine into the human eye. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 1996;12:499–502. doi: 10.1089/jop.1996.12.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hurley IW, Brooks AM, Reinehr DP, et al. Identifying anterior segment crystals. Br J Ophthalmol. 1991;75:329–31. doi: 10.1136/bjo.75.6.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iwata F, Kuehl EM, Reed GF, et al. A randomized clinical trial of topical cysteamine disulfide (cystamine) versus free thiol (cysteamine) in the treatment of corneal cystine crystals in cystinosis. Mol Genet Metab. 1998;64:237–42. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1998.2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jones NP, Postlethwaite RJ, Noble JL. Clearance of corneal crystals in nephropathic cystinosis by topical cysteamine 0.5% Br J Ophthalmol. 1991;75:311–2. doi: 10.1136/bjo.75.5.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaiser-Kupfer MI, Caruso RC, Minkler DS, et al. Long-term ocular manifestations in nephropathic cystinosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104:706–11. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050170096030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaiser-Kupfer MI, Chan CC, Rodrigues M, et al. Nephropathic cystinosis: immunohistochemical and histopathologic studies of cornea, conjunctiva and iris. Curr Eye Res. 1987;6:617–22. doi: 10.3109/02713688709025222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaiser-Kupfer MI, Datiles MB, Gahl WA. Clear graft two years after keratoplasty in nephropathic cystinosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;105:318–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(88)90018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaiser-Kupfer MI, Datiles MB, Gahl WA. Corneal transplant in boy with nephropathic cystinosis. Lancet. 1987;1:331. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaiser-Kupfer MI, Fujikawa L, Kuwabara T, et al. Removal of corneal crystals by topical cysteamine in nephropathic cystinosis. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:775–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198703263161304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaiser-Kupfer MI, Gazzo MA, Datiles MB, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of cysteamine eye drops in nephropathic cystinosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:689–93. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070070075038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kalatzis V, Cherqui S, Antignac C, et al. Cystinosin, the protein defective in cystinosis, is a H(+)-driven lysosomal cystine transporter. EMBO J. 2001;20:5940–9. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.5940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Katz B, Melles RB, Schneider JA, et al. Corneal thickness in nephropathic cystinosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73:665–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.73.8.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Katz B, Melles RB, Schneider JA. Crystal deposition following keratoplasty in nephropathic cystinosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107:1727–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020809012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Katz B, Melles RB, Schneider JA. Recurrent crystal deposition after keratoplasty in nephropathic cystinosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;104:190–1. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(87)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Katz B, Melles RB, Schneider JA. Glare disability in nephropathic cystinosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105:1670–1. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1987.01060120068026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Katz B, Melles RB, Schneider JA. Contrast sensitivity function in nephropathic cystinosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105:1667–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1987.01060120065025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Katz B, Melles RB, Schneider JA. Corneal sensitivity in nephropathic cystinosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;104:413–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(87)90233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kenyon KR. Conjunctival biopsy for diagnosis of lysosomal disorders. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1982;82:103–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kenyon KR, Sensenbrenner JA. Electron microscopy of cornea and conjunctiva in childhood cystinosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1974;78:68–76. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(74)90011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kimonis VE, Troendle J, Rose SR, et al. Effects of early cysteamine therapy on thyroid function and growth in nephropathic cystinosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:3257–61. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.11.7593434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kleta R, Blair SC, Bernardini I, et al. Keratopathy of multiple myeloma masquerading as corneal crystals of ocular cystinosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:410–2. doi: 10.4065/79.3.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leipert KP, Morche F, Ehrich JH. [Infantile nephropathic cystinosis: electro-ophthalmologic findings in kidney transplant patients and their mothers] Fortschr Ophthalmol. 1987;84:287–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.MacDonald IM, Noel LP, Mintsioulis G, et al. The effect of topical cysteamine drops on reducing crystal formation within the cornea of patients affected by nephropathic cystinosis. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1990;27:272–4. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19900901-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Markello TC, Bernardini IM, Gahl WA. Improved renal function in children with cystinosis treated with cysteamine. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1157–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304223281604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Melles RB, Schneider JA, Rao NA, et al. Spatial and temporal sequence of corneal crystal deposition in nephropathic cystinosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;104:598–604. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(87)90171-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mungan N, Nischal KK, Héon E, et al. Ultrasound biomicroscopy of the eye in cystinosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:1329–33. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.10.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Okami T, Nakajima M, Higashino H, et al. [Ocular manifestations in a case of infantile cystinosis] Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;96:1341–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Read J, Goldberg MF, Fishman G, et al. Nephropathic cystinosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1973;76:791–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(73)90579-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Richard G, Kroll P. [Retinal changes in cystinosis] Ophthalmologica. 1983;186:211–8. doi: 10.1159/000309288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Richler M, Milot J, Quigley M, et al. Ocular manifestations of nephropathic cystinosis. The French-Canadian experience in a genetically homogeneous population. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:359–62. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080030061039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sanderson PO, Kuwabara T, Stark WJ, et al. Cystinosis. A clinical, histopathologic, and ultrastructural study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1974;91:270–4. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1974.03900060280006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schneider JA, Katz B, Melles RB. Update on nephropathic cystinosis. Pediatr Nephrol. 1990;4:645–53. doi: 10.1007/BF00858644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schneider JA, Schulman JD. Cystinosis: a review. Metabolism. 1977;26:817–39. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(77)90070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schneider JA, Verroust FM, Kroll WA, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of cystinosis. N Engl J Med. 1974;290:878–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197404182901604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Scouras J, Faggioni R. Ocular manifestations of cystinosis. Ophthalmologica. 1969;159:24–30. doi: 10.1159/000305884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stefani FH, Vogel S. Adult cystinosis: electron microscopy of the conjunctiva. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1982;219:143–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02152300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Theodoropoulos DS, Krasnewich D, Kaiser-Kupfer MI, et al. Classic nephropathic cystinosis as an adult disease. JAMA. 1993;270:2200–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Thoene JG, Oshima RG, Crawhall JC, et al. Cystinosis. Intracellular cystine depletion by aminothiols in vitro and in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1976;58:180–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI108448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Town M, Jean G, Cherqui S, et al. A novel gene encoding an integral membrane protein is mutated in nephropathic cystinosis. Nat Genet. 1998;18:319–24. doi: 10.1038/ng0498-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tsilou E, Csaky K, Rubin BI, et al. Retinal visualization in an eye with corneal crystals using indocyanine green videoangiography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:123–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tsilou ET, Rubin BI, Reed G, et al. Nephropathic cystinosis: posterior segment manifestations and effects of cysteamine therapy. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1002–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tsilou ET, Rubin BI, Reed GF, et al. Age-related prevalence of anterior segment complications in patients with infantile nephropathic cystinosis. Cornea. 2002;21:173–6. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200203000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tsilou ET, Thompson D, Lindblad AS, et al. A multicentre randomised double masked clinical trial of a new formulation of topical cysteamine for the treatment of corneal cystine crystals in cystinosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:28–31. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wan WL, Minckler DS, Rao NA. Pupillary-block glaucoma associated with childhood cystinosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986;101:700–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(86)90773-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wong VG. Ocular manifestations in cystinosis. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1976;12:181–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wong VG, Kuwabara T, Brubaker R, et al. Intralysosomal cystine crystals in cystinosis. Invest Ophthalmol. 1970;9:83–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wong VG, Lietman PS, Seegmiller JE. Alterations of pigment epithelium in cystinosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1967;77:361–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1967.00980020363014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yamamoto GK, Schulman JD, Schneider JA, et al. Long-term ocular changes in cystinosis: observations in renal transplant recipients. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1979;16:21–5. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19790101-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]